Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this prospective study was to compare the functional results and patient satisfaction after arthroscopic shoulder capsular release in patients with idiopathic and posttraumatic stiff shoulder.

Methods

The study included 50 patients who underwent arthroscopic capsular release after failure of conservative treatment. The etiology of stiffness was either idiopathic (25 patients) or post-traumatic (25 patients). There were 28 women and 22 men with an average age of 49 years (range, 32–70 years). All patients were treated with physical therapy for a mean of six months (range, 3–12 months) before surgery. Range of motion was measured three times: 48 hours after surgery, then one month and six months after surgery.

Results

Constant score showed improvement for both groups of patients in the period of six months after surgery. In the group with idiopathic stiffness the score increased from 36 to 86, while in the group with post-traumatic stiff shoulder the score advanced from 32 to 91. The idiopathic stiff shoulder group had an improved active forward flexion from 90 to 161°, external rotation from 10 to 40°, and internal rotation from L5 to L1. In the post-traumatic stiff shoulder groupthe forward flexion was improved from 95 to 170°, external rotation from 13 to 40° and internal rotation from L4 to L1.

Conclusion

There was an improvement of range of motions and patients' satisfaction after arthroscopic shoulder capsular release and manipulation under anesthesia, equally in idiopathic and post-traumatic stiff shoulder, compared to the situation before surgery. Post-traumatic contracture patients expressed higher level of satisfaction with their shoulder function than the idiopathic stiff shoulder patients.

Keywords: Idiopathic, Frozen shoulder, Post-traumatic stiff shoulder, Arthroscopic capsular release, Patient satisfaction

Introduction

Stiffness of shoulder is a common disorder [1]. There is restriction of passive and active range of motion of the shoulder, which is associated with pain. Stiff shoulder can be divided by aetiology into primary or secondary, determined by the presence or absence of causes, such as trauma [2]. Primary stiff shoulder, well known as frozen shoulder, is a common disorder with idiopathic form. Its prevalence is reported to be 2–5 % [3]. Secondary shoulder stiffness may occur after surgery or trauma such as fracture, dislocation or injury of the soft tissue. The stiffness is typically due to a combination of capsular contracture and extracapsular adhesions [4]. The initial treatment is always conservative. Several studies have shown refractory shoulder stiffness where conservative treatment fails and where there is long-term residual pain and limitation of motion [5]. This type of patient needs surgery. The aim of this prospective study was to compare the functional results and patient satisfaction after arthroscopic capsular release and rehabilitation in patients with idiopathic and post-traumatic stiff shoulder.

Materials and methods

This study included two groups of patients who underwent arthroscopic capsular release after failure of conservative treatment. The aetiology of stiffness was either idiopathic or post-traumatic. Patients with osteoarthritis, calcific tendinitis or previous surgery were excluded from the study. Fifty patients underwent arthroscopic capsular release and were followed-up for six months. There were 28 women and 22 men, with an average age of 49 years (range, 32–70 years). The first group consisted of 25 patients with idiopathic or frozen shoulder, 18 women and seven men, with an average age of 49 years (range 40–65 years). There were six patients with diabetes mellitus. There were no patients with malignanacies, heart problems, collagen disease or arthritis. The second group consisted of 25 patients with post-traumatic stiff shoulder, 19 men and six women, with an average age of 42 years (range, 32–70 years). All patients were treated with physical therapy for a mean of six months (range, three to 12 months) before undergoing arthroscopic capsular release. The indication for surgery was continued pain and restriction of movement.

All patients were prospectively evaluated using history, clinical examination, plain radiographs, subjective satisfaction, Constant score and visual analog score (VAS) for pain. Constant score was calculated as an absolute numeric value. Pain was measured by use of a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain). Active and passive range of motion was determined by goniometer in relationship to the long axis of the thorax. Motion was recorded for forward flexion (FX), external rotation (ER) of the side, and internal rotation (IR) to a spinal segment. In the group with idiopathic stiff shoulder, forward flexion (FX) was 90°, external rotation (ER) 10, internal rotation (IR) L5, whereas the group with post-traumatic stiff shoulder range of motion was similar, forward flexion (FX) was 95°, external rotation (ER) 13°, and internal rotation (IR) L4.

Twenty-five patients had shoulder stiffness due to trauma. Nine patients had shoulder stiffness after anterior dislocation with or without fracture of greater tuberosity and six patients fracture of proximal humerus. Eleven patients had shoulder stiffness after clear injury without fracture, dislocation or other soft tissue trauma.

Range of motion was measured 48 hours after surgery (during continuous regional analgesia), one month and six months after surgery.

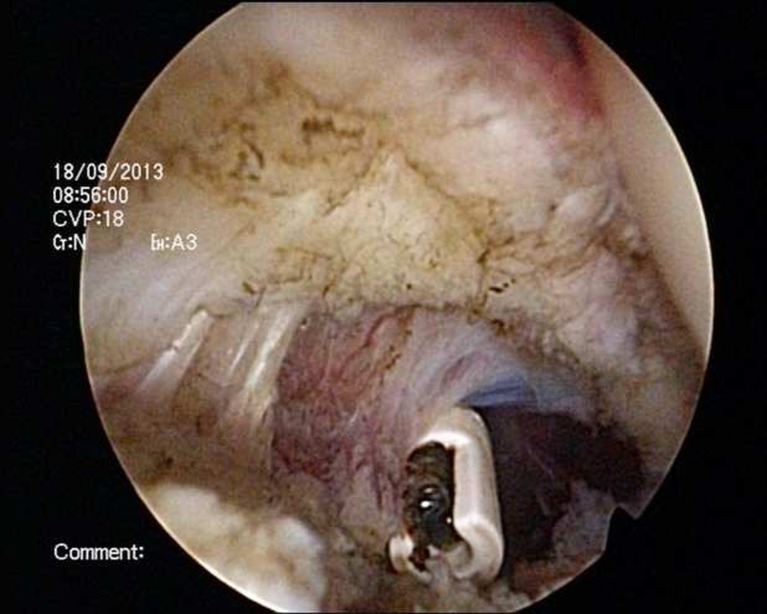

Arthroscopic capsular release

The surgery was performed in a routine way as previously described [6]. All patients were operated on in the beach-chair position. Passive range of motion was documented under general anaesthesia and interscalene block before surgery. Standard posterior portal was used. After insertion of the arthroscope, anterior portal was established by using an ordinary needle which was placed in a rotator interval from outside-in. Release of the rotator interval was first performed, and then contracted, then the anterior capsule was released followed by the posterior capsule by a radiofrequency device looking from anterior portal (Figs. 1 and 2). A small part of the capsule in the axillar region was not released. After the arthroscopic release, manipulation of the shoulder was performed. In all cases minimal force was required to restore full range of motion. Subacromial bursectomy was performed only in postraumatic cases to exclude some damage of subacromial structures such as partial bursal rotator cuff tear or damage of the anterior-inferior edge of the acromion.

Fig. 1.

Anterior capsular release in a patient with post-traumatic stiff shoulder

Fig. 2.

Posterior capsular release in a patient with post-traumatic stiff shoulder

Rehabilitation

All patients were operated on under general anaesthesia and interscalene block. During the post-surgery treatment, all patients were continuously attached to intravenous drip with a low level of local anaesthetics throughout the period of 48 hours. Physical therapy was started on the day of surgery and it involved passive exercises with the assistance of a physiotherapist, and continuous passive exercises (Kinetec, Patterson Medical, France), all performed in the first 48 hours. Immediately upon release from hospital, patients continued the physical therapy.

Results

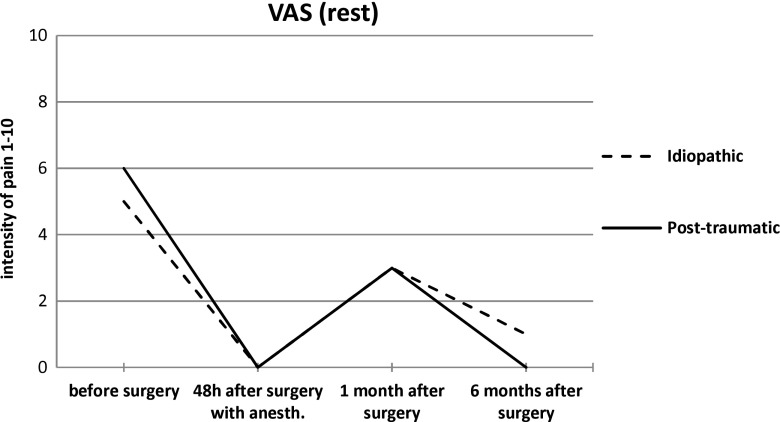

Visual analog score (VAS)

Before the surgery the idiopathic stiff shoulder group had rest VAS which amounted to 5 and 8 in the state of activity, whereas the post-traumatic stiff shoulder group had rest VAS of 6 and activity VAS of 9 (Figs. 3 and 4). All patients were being given continuous regional anaesthesia throughout the 48 hour post-surgery period, and in that period in both groups both parameters of VAS (rest and activity) were 0, which was expected. A month after the surgery both groups had rest VAS of 3, and the activity VAS of 6. Six months after surgery the idiopathic stiff shoulder patients were measured with rest VAS of 1 and activity VAS of 2. On the other hand, the post-traumatic stiff shoulder patients were measured with rest VAS of 0 and activity VAS of 1.

Fig. 3.

Visual analog score in rest state presented in both patient groups throughout the period of monitoring

Fig. 4.

Visual analog score in the activity state presented in both patient groups throughout the period of monitoring

Constant score

Before surgery the idiopathic stiff shoulder group had Constant score of 36, and the post-traumatic stiff shoulder group 32 (Fig. 5). Patients accomplish the final results of ultimate movement in all planes in the period of three to six months after the surgery. Six months after rehabilitation the Constant score of the idiopathic stiff shoulder patients was 86, and of the post-traumatic stiff shoulder patients was 91. Higher scores achieved by the post-traumatic stiff shoulder patients are explained by the fact that they are a somewhat younger and more motivated age group.

Fig. 5.

Constant score presented for both groups of patients before and after surgery

Patient satisfaction post surgery and after the rehabilitation

Six months after the surgery the patients were asked to which extent they were satisfied with their arm function. All patients in both groups expressed their complete satisfaction. Twenty patients who suffered from post-traumatic contracture and 17 patients with idiopathic contracture reported they were very satisfied. Five patients with post-traumatic contracture and 18 with idiopathic reported they were satisfied. In total 37 patients in both groups said that they were very satisfied and 13 patients claimed they were satisfied. None of the patients in either group showed dissatisfaction with the surgery outcome.

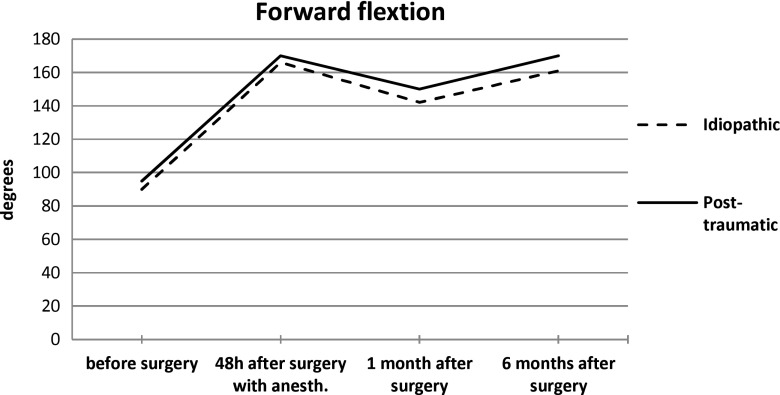

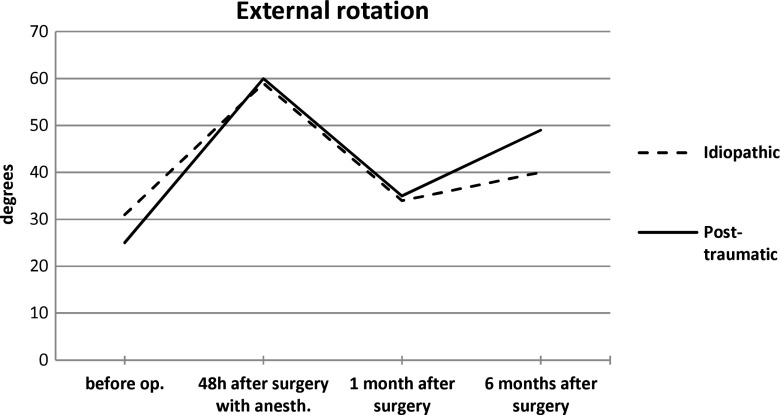

Mobility

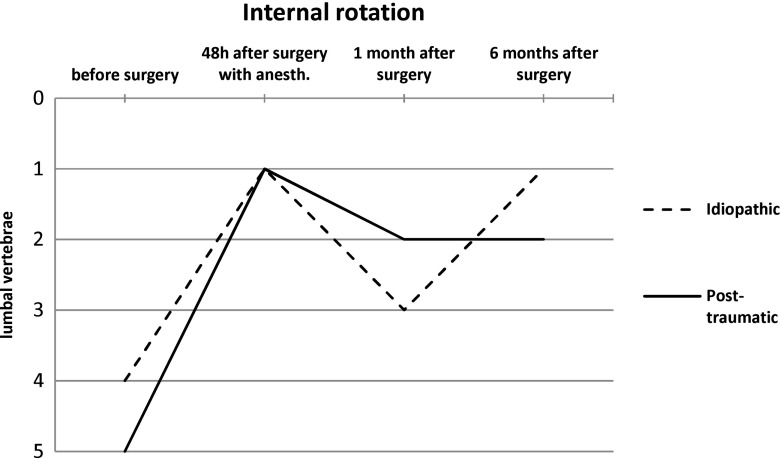

The first shoulder mobility measuring was conducted shortly before the surgery under general anaesthesia and interscalene block. For the idiopathic stiff shoulder group there was a 90° forward flexion, a 10° external rotation and internal rotation to L5. For the post-traumatic stiff shoulder group the result was a 95° forward flexion, a 13° external rotation and internal rotation to L4 (Figs. 6, 7 and 8). For the first 48 hour post surgery the patients were being given regional anaesthesia. In that period another measurement was conducted which showed passive forward flexion of 166° for the idiopathic stiff shoulder group, external rotation of 59° and internal rotation to L1. For the post-traumatic stiff shoulder patients passive forward flexion was 170°, external rotation 60° and internal rotation to L1. A month after the surgery both groups of patients had reduced mobility in all directions when compared with the 48 hour post-surgery results. The idiopathic stiff shoulder group was measured active forward flexion of 142°, external rotation of 34° and internal rotation to L3. The post-traumatic stiff shoulder flexion was 150°, external rotation 35° and internal rotation to L2. Six months after the surgery the active mobility in the idiopathic stiff shoulder group showed flexion of 161°, external rotation of 40° and internal rotation to L1. The post-traumatic stiff shoulder patients had flexion of 170°, external rotation of 49° and internal rotation to L1. In both groups of patients mobility increased significantly after the surgery and rehabilitation. Comparing the ultimate results of both groups, it is evident that the patients with post-traumatic stiff shoulder achieved a somewhat better flexion and external rotation (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Shoulder forward flexion presented in both patient groups throughout the period of monitoring

Fig. 7.

External shoulder rotation presented in both patient groups throughout the period of monitoring

Fig. 8.

Internal shoulder rotation presented in both patient groups throughout the period of monitoring

Table 1.

Results before surgery, 48 h, one and six months after arthroscopic shoulder capsular release

| Measure | Idiopathic | Post-traumatic |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 25 | 25 |

| Age (years) | 49 (40–65) | 42 (32–70) |

| VAS (pain) at rest preoperative | 5 | 6 |

| One month | 3 | 3 |

| Six months | 1 | 0 |

| Constant score | ||

| Preoperative | 36 | 32 |

| Postoperative six months | 86 | 91 |

| Forward flexion (degrees) | ||

| Preoperative | 90 | 95 |

| Postoperative 48 h | 166 | 170 |

| Postoperative one month | 142 | 150 |

| Postoperative six months | 161 | 170 |

| External rotation (degrees) | ||

| Preoperative | 10 | 13 |

| Postoperative 48 h | 59 | 60 |

| Postoperative one month | 34 | 35 |

| Postoperative six months | 40 | 49 |

| Internal rotation (degrees) | ||

| Preoperative | L5 | L4 |

| Postoperative 48 h | L1 | L1 |

| Postoperative one month | L3 | L3 |

| Postoperative six months | L1 | L1 |

Discussion

The natural course of idiopathic or frozen shoulder disease is well-known [7–9]. Physical therapy cannot make a difference at the initial phase, but at the later stage when there is recovery of shoulder mobility [10]. As opposed to idiopathic stiff shoulder, physical therapy does not show significant results in a certain number of patients suffering from posttraumatic contracture which is the result of a fracture, dislocation, damage of soft tissue structures, and especially in patients who did not undergo a timely or adequate physical therapy. In such cases, after conservative treatment which showed no results, it is necessary to perform surgery [11]. The most common cause of post-traumatic contracture is shortening of soft tissue, primarily inflammations, and later capsular thickening. Recently, the most dominant method used is arthroscopic capsular release, which improves shoulder mobility to a great extent and reduces pain [12, 13]. Our results show it clearly. Other authors have come to similar results and have written about the success of arthroscopic capsular release in frozen shoulder and posttraumatic contracture [14–16]. In our prospective study the patients who were suffering from post-traumatic contracture have recovered more rapidly and have achieved a better final result regarding mobility and their satisfaction even though the result was not statistically significant. Elhassan et al. [6] reported on 115 patients who underwent arthroscopic capsular release for painful shoulder stiffness. The patients were divided into three groups according to the aetiology of stiffness: post-traumatic (26 patients), postsurgical (48 patients), and idiopathic (41 patients). The overall subjective shoulder value in all groups improved from 29 to 73 %. The mean pain score decreased from 7.5 to 1. In the idiopathic group the mean active forward flexion, external rotation and internal rotation increased from 100°, 14°, and the L5 vertebral level to 140°, 35°, and the T12 vertebral level, respectively. In the post-traumatic group the mean active forward flexion, external rotation and internal rotation increased from 96°, 17°, and the sacrum vertebral level to 134°, 35°, and the T10 vertebral level, respectively. We have similar results in our study. In the idiopathic group the mean active forward flexion, external rotation and internal rotation increased from 90°, 10°, and the L5 vertebral level to 161°, 40°, and the L1 vertebral level, respectively. In the post-traumatic group the mean active forward flexion, external rotation and internal rotation increased from 95°, 13°, and the L4 vertebral level to 170°, 49°, and the L1 vertebral level, respectively.

Gerber et al. [17] reported on the results of arthroscopic capsular release in 45 patients with shoulder stiffness. The patients were divided according to the aetiology of stiffness into three groups: idiopathic (nine patients), postoperative (21 patients), and post-traumatic (15 patients). All patients reported an improvement of pain and range of motion. However, the outcome was better after surgery of frozen shoulder compared to postoperative and post-traumatic groups. Patients with post-traumatic shoulder stiffness had lower improvement than the idiopathic and postoperative patients.

Nicholson et al. [14] report a considerable improvement of mobility and shoulder function along with reduced pain in the group of 68 patients who were divided into five groups and who underwent arthroscopic capsular release. The groups were divided into idiopathic, postsurgical, post-traumatic, diabetic and subacromial impingement syndrome. Nicholson reported similar results for all groups of patients. In most cases the stiff shoulder patients from the postsurgical group had an arthroscopic subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair.

Our study showed better results for the post-traumatic stiff shoulder than the idiopathic or frozen shoulder. Gerber’s and Nicholson’s results differ from ours. Gerber reported better results in the idiopathic group than the postsurgical one, and both groups were better than the post-traumatic group. A possible reason for that might be the fact that many post-traumatic patients suffered from dislocations and fractures, as opposed to our post-traumatic group whose stiff shoulder was a consequence of soft structure trauma in 11 out of 25 patients (44 %), patients who had a proximal humerus fracture without a great displacement, and patients who had a shoulder dislocation—and all of whom had initially been conservatively treated.

Levy et al. [4] reported that the group, consisting of 21 patients who suffered from post-traumatic shoulder contracture as a consequence of fracture, underwent an arthroscopic capsular release, performed immediately after the surgery, and experienced a considerable mobility improvement. Mobility was decreased in the first six months, but after that the patients’ condition improved. The authors explain that the patients were on their own in the first six months, where physical therapy was involved. After the period of six months, a natural healing process occurred. The most important parameters of mobility in our study occurred 48 hours after the surgery while the patients had still been under the influence of analgesics. After that, a month after the surgery, a decreased shoulder mobility occurred in both groups, but in the period of six months after the surgery, mobility gradually increased; however, it did not increase to the level of mobility just after the surgery. The reason for that is a complete lack of pain due to analgesic effect immediately after the surgery and a later tendency to soft tissue structure shortening, especially the joint capsule.

Complications occurring after arthroscopic capsular release involve recurrence [18], axillary nerve palsy [19] and post-surgical shoulder dislocation [5].

Our series of 50 patients who were monitored for the period of six months did not show recurrence, or axillary nerve palsy or shoulder instability after the surgery. In order to avoid a possible axillary nerve damage, part of the joint capsule remained intact. During manipulation, which was performed after opening rotator interval and releasing the anterior and posterior part of the joint capsule, full shoulder mobility was achieved without any difficulties, whereby the sound of a dry twig crack was usually heard when an arm elevation was being performed.

The drawback of this study is a six-month-monitoring period after arthroscopic capsule release. However, according to the long-term results of monitoring over a duration of seven years, there was no significant difference found with respect to mobility, when compared to short-term monitoring [20].

Conclusion

There was a significant improvement of range of motion and pain relief after arthroscopic capsular release and manipulation under general anaesthesia, equally in both groups of idiopathic and post-traumatic stiff shoulder, compared to the situation before surgery. The post-traumatic contracture patients are more satisfied with their shoulder function than the idiopathic stiff shoulder patients. Arthroscopic shoulder capsular release and manipulation under general anaesthesia in patients with idiopathic or post-traumatic stiff shoulder, followed by an early rehabilitation, is a successful way to restore full function of the shoulder joint.

References

- 1.Warner JJ. Frozen shoulder: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(3):130–140. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins EF, Thomas WJ, Corcoran JP, Kirubanandan R, Beynon CR, Sayers AE, Woods DA. The outcome of manipulation under general anesthesia for the management of frozen shoulder in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Should Elb Surg. 2012;21(11):1492–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89(7):928–932. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy O, Webb M, Even T, Venkateswaran B, Funk L, Copeland SA. Arthroscopic capsular release for posttraumatic shoulder stiffness. J Should Elb Surg. 2008;17(3):410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner JJ, Allen A, Marks PH, Wong P. Arthroscopic release for chronic, refractory adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(12):1808–1816. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elhassan B, Ozbaydar M, Massimini D, Higgins L, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic capsular release for refractory shoulder stiffness: a critical analysis of effectiveness in specific etiologies. J Should Elb Surg. 2010;19(4):580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ando A, Sugaya H, Hagiwara Y, Takahashi N, Watanabe T, Kanazawa K, Itoi E. Identification of prognostic factors for the nonoperative treatment of stiff shoulder. Int Orthop. 2013;37(5):859–864. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1859-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clipsham K, Rees JL, Carr JA. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Should Elb Surg. 2008;17(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarlat MM, Harryman DT. Management of the diabetic stiff shoulder. Instr Course Lect. 2000;49:283–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griggs SM, Ahn A, Green A. Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. A prospective functional outcome study of nonoperative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(10):1398–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tauro CJ, Paulson M. Shoulder stiffness. Arthroscopy. J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2008;24(8):949–955. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Carli A, Vadalà A, Perugia D, Frate L, Iorio C, Fabbri M, Ferretti A. Shoulder adhesive capsulitis: manipulation and arthroscopic arthrolysis or intra-articular steroid injections? Int Orthop. 2012;36(1):101–106. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1330-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dattani R, Ramasamy V, Parker R, Patel VR. Improvement in quality of life after arthroscopic capsular release for contracture of the shoulder. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(7):942–946. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B7.31197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson GP. Arthroscopic capsular release for stiff shoulders: effect of etiology on outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):40–49. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaufils P, Prévot N, Boyer T, Allard M, Dorfmann H, Frank A, Kelbérine F, Kempf JF, Molé D, Walch G. Arthroscopic release of the glenohumeral joint in shoulder stiffness: a review of 26 cases. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(1):49–55. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harryman DT, Matsen FA, Sidles JA. Arthroscopic management of refractory shoulder stiffness. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(2):133–147. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber C, Espinosa N, Perren TG. Arthroscopic treatment of shoulder stiffness. Clin Orthop Relat Res Sep. 2001;390:119–128. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson L, Dalziel R, Story I. Frozen shoulder: a 12-month clinical outcome trial. J Should Elb Surg. 2000;9(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(00)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harryman DT., 2nd Shoulders: frozen and stiff. Instr Course Lect. 1993;42:247–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Lievre HMJ, Murrell GAC. Long-term outcomes after arthroscopic capsular release for idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(13):1208–1216. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]