Abstract

Purpose

The optimal design for a cemented femoral stem remains a matter of debate. Over time, the shape, surface finish and collar have all been modified in various ways. A clear consensus has not yet emerged regarding the relative merits of even the most basic design features of the stem. We undertook a prospective randomised trial comparing surface finish and the effect of a collar on cemented femoral component subsidence, survivorship and clinical function.

Methods

One hundred and sixty three primary total hip replacement patients were recruited prospectively and randomised to one of four groups to receive a cemented femoral stem with either a matt or polished finish, and with or without a collar.

Results

At two years, although there was a trend for increased subsidence in the matt collarless group, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.18). At a mean of 10.1 years follow-up, WOMAC scores for the surviving implants were good, (Range of means 89–93) without significant differences. Using revision or radiographic loosening as the endpoint, survivorship of the entire cohort was 93 % at 11 yrs, (CI 87–97 %). There were no significant differences in survivorship between the two groups with polished stems or the two groups with matt stems. A comparison of the two collarless stems demonstrated a statistically significant difference in survivorship between polished (100 %) and matt (88 %) finishes (p = 0.02).

Conclusions

In the presence of a collar, surface finish did not significantly affect survivorship or function. Between the two collarless groups a polished surface conferred an improved survivorship.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Hip, Randomised, Bone Cement, Stem

Introduction

Since the earliest cemented total hip replacement, many different stem designs have been used; shape, surface finish and collar have all been modified in various ways. Comparison of the impact of each of these variables across published series is difficult, as the stems being investigated often differ in more ways than one. Each factor has a potential effect on the mechanics of the stem and the stem–cement interface; thus, the relative contribution of each is hard to elicit. In addition, there are significant contributions from both patient characteristics and surgical techniques that may influence outcome [1]. The number of factors contributing to success or failure may explain why a clear consensus has not yet emerged regarding the relative merits of even the most basic design features of the stem. Variability of results even between different surgeons using the same implant demonstrates the unreliability of comparisons between published results of individual implants. The only way to establish the optimal design of implant is by rigorous scientific assessment through a prospective randomised trial, and such studies are few [2].

The design rationale of modern stems and the mechanism of stability within the cement mantle can be broadly divided into loaded-taper and composite-beam designs [3]. Loaded-taper stems are expected to migrate in the initial phases after implantation to a stable position. A polished finish, and thus a weak cement bond, might be preferred with this concept, as this, along with a hollowed centraliser used in some designs, allows progressive subsidence to a position of stability without generating metal and cement debris at the cement–stem interface as a result of micromovement whilst also reducing the development of channels at the interface in which debris can travel [4].

A composite-beam stem has features such as a collar or altered geometry or surface finish intended to achieve and maintain initial stability, prevent subsidence and transmit load directly to the cement mantle [3]. The advantage might lie in reducing micromotion at the cement/implant interface, thereby reducing generation of particulate debris, variation in hydraulic pressure, and tensile stresses within the cement that might lead to cracking. These benefits may not be achieved, however, if debonding of the interface occurs; features such as surface roughening designed to prevent movement may then compound the adverse consequences when movement does occur [5, 6]. This may account for some of the concerns reported when matt surfaces are used with loaded-taper-design stems [7, 8]. The usefulness of a collar on a stem is a matter of some debate. Its presence has the potential to transfer load directly from the implant to the medial cement mantle and the medial femoral neck; the ensuing benefit is reduced stress in the proximal cement mantle and decreased stress shielding of the proximal femur [9]. This altered loading may in turn have a detrimental effect on distal cement stresses [10, 11]. Even with a collar, micromotion can still occur, and it does not always prevent early resorption of the medial femoral neck [12, 13]. This indicates that a collar may not be of primary importance in preventing implant instability, and evidence of disuse atrophy of calcar bone under a well-fitting collar suggests that with a well-fixed stem, the collar may be redundant even when particular effort has been taken to ensure close contact between collar and bone.

We undertook a prospective, randomised trial in order to determine the effect of a collar and alterations in surface finish on cemented femoral stems.

Patients and methods

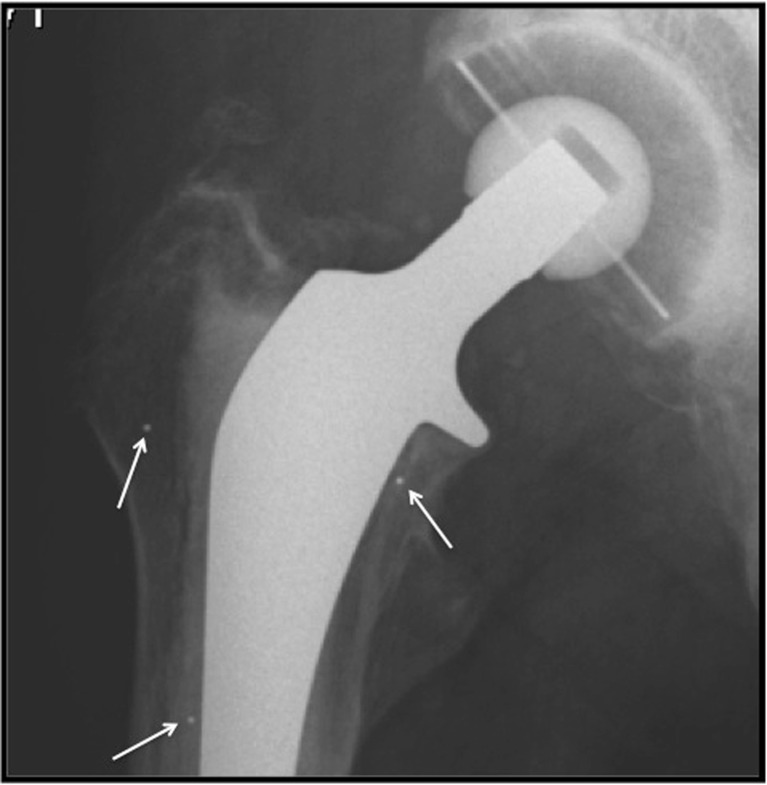

The Ultima LX stem, (Depuy, IN, USA) is a cobalt–chromium (CoCr) alloy, straight tapered stem with a lateral flange (Fig 1), and four variations were used in this study. Collared and collarless versions were polished to give a surface roughness of 0.1 μm, or sand blasted to give a matt finish with a surface roughness of 2 μm. The stems were otherwise identical.

Fig. 1.

Anteroposterior (AP) profile of collared and noncollared stems

The regional ethics committee approved the study design. All patients aged between 60 and 80 years with a diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis were invited to enrol. Patients undergoing revision surgery, with a history of previous hip sepsis or those likely to remain housebound once rehabilitation was complete, were excluded from the study. Power calculations were performed for the primary outcome of stem subsidence using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect a difference between treatment group means of 0.5 standard deviations (SD) at a significance level of p < 0.05. In order to achieve 80 % power, a minimum of 160 patients, 40 in each group, was required. In the end, 163 patients (163 hips) were prospectively recruited between 1997 and 2003. Recruitment was then ceased, as the stems, manufactured specifically for the trial, were reaching the end of their useable shelf life. All operations were performed at a single centre by one of four consultant surgeons. Randomisation was via a previously prepared sealed envelope opened in theatre once the patient had been anaesthetised. A standard anterolateral approach and cementing technique were used in all cases. The stems were coupled with 28-mm ceramic heads and cemented polyethylene acetabular components (Ultima™ DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA). Three tantalum marker beads were implanted into the proximal femur at the time of surgery (Fig. 2). Patients followed a standard rehabilitation programme, with full weight bearing from the first postoperative day.

Fig. 2.

Radiograph showing positions of marker beads implanted in proximal femur

The primary outcome measure was stem subsidence over the first two years postoperatively. This was calculated after digitising radiographs taken on the first postoperative day, then at six months and one and two years. Measurements were taken from the centre of the femoral head to marker beads in the femur that were visible on all follow-up radiographs. Secondary outcome measures were clinical function and implant survivorship. During the final follow-up period, between April and May 2010, all surviving patients were contacted via telephone or post. Function was evaluated using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index, (WOMAC). Those who were able to travel were invited to attend for a follow-up radiograph. Hospital notes were reviewed for all revisions, and all latest radiographs were evaluated for any evidence of loosening in the zones as defined by Gruen et al. [14].

Statistical analysis

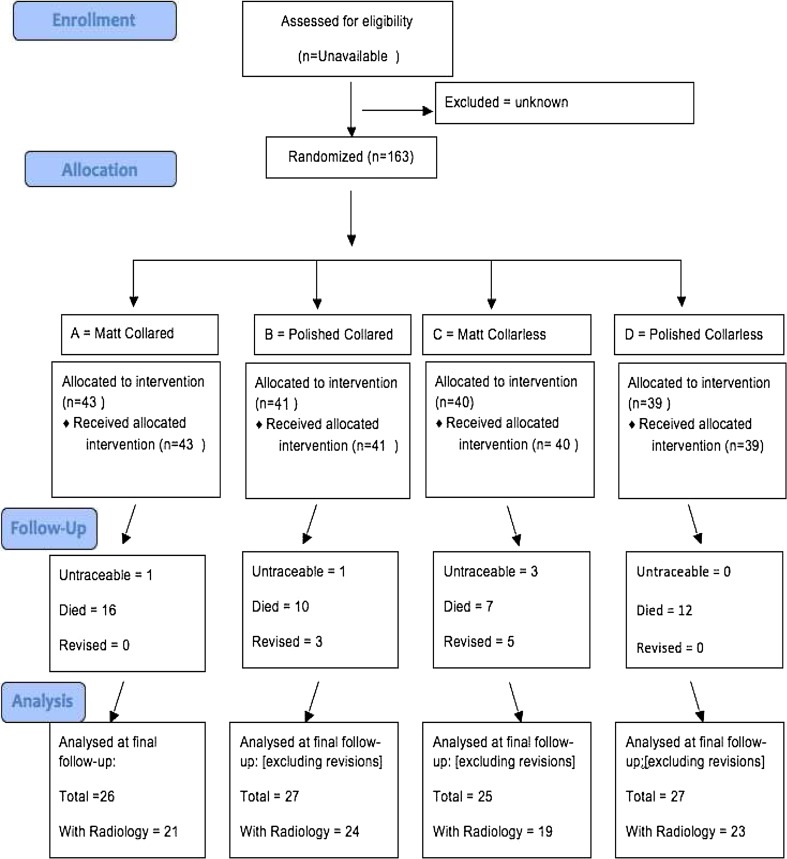

Differences in mean stem subsidence at two years were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in WOMAC scores between groups were analysed with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Survival analysis was performed using the life table method, with binomial confidence intervals (CIs) calculated from the effective number at risk using Rothman’s equation [15, 16]. The endpoints were defined as stem revision for aseptic loosening or radiographic evidence of loosening as shown by progressive radiolucency in one or more Gruen zones. The cumulative survival rates for the four groups were compared using the log-rank test. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the study is shown in the Appendix.

Results

The groups were well matched in terms of numbers, mean age, preoperative hip score and mean follow-up time (Table 1). At the last review of our 163 patients, at a mean of 10.1 range 6.5–12.9) years, 44 patients had died, eight had undergone revision (5.5 %) and five had been lost to follow-up and were untraceable, which left 105 patients with surviving stems. All patients recorded a WOMAC score; 18 patients across all four groups were unable to travel for a follow-up radiograph at last review, as shown in the CONSORT diagram. Two patients, one in group A and one in group C, had radiographic evidence of stem loosening.

Table 1.

Breakdown of the four groups after randomisation

| Group | Number | Mean | Sex | Preoperative Harris Hip Score | Mean length of follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M:F | ||||

| A (matt collared) | 43 | 72 | 15:28 | 29 | 9.7 |

| B (polished collared) | 41 | 71 | 20:21 | 25 | 10.3 |

| C (matt collarless) | 40 | 71 | 14:26 | 27 | 9.9 |

| D (polished collarless) | 39 | 71 | 14:27 | 29 | 10.2 |

Three patients had significant complications, none of which impacted on stem survival. There were two periprosthetic fractures in the collarless matt stem groups: One occurred at six months that was thought to be related to a breach of the femur during broaching the femur at surgery. The other followed a road accident eight months after operation. Both were treated at the time of injury with internal fixation, and both are still functioning well, with WOMAC scores of 90 at 12.4 years and 10.3 years, respectively. The latter stem had migrated only 0.4 mm at six months prior to the accident. One patient with a matt collarless stem had two dislocations at nine days and four weeks postoperatively but then achieved stability and a WOMAC score of 97 at 8.7 years postoperatively.

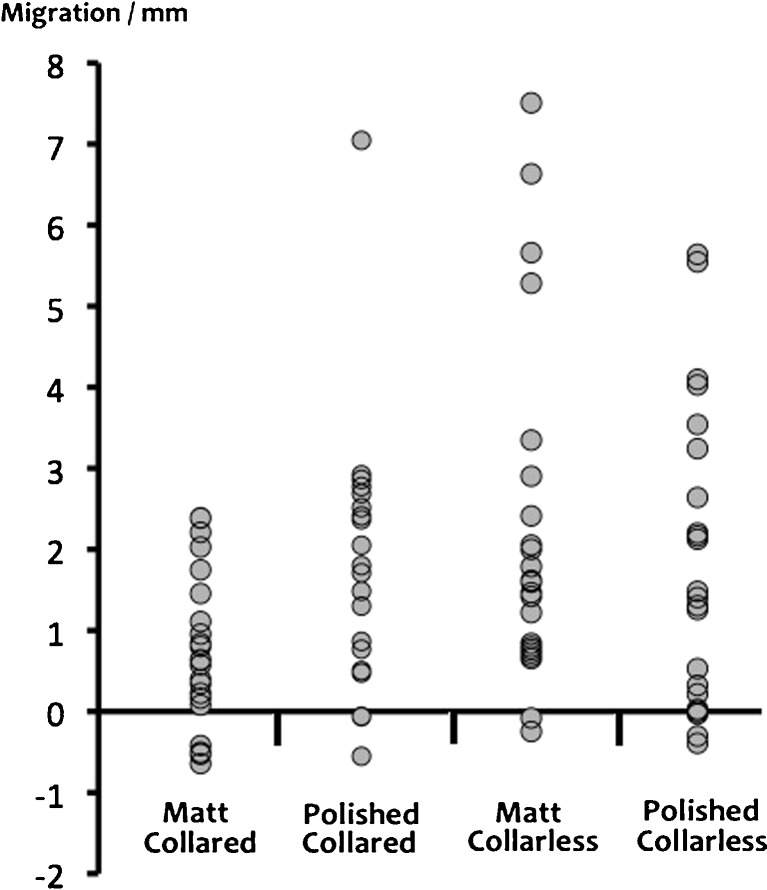

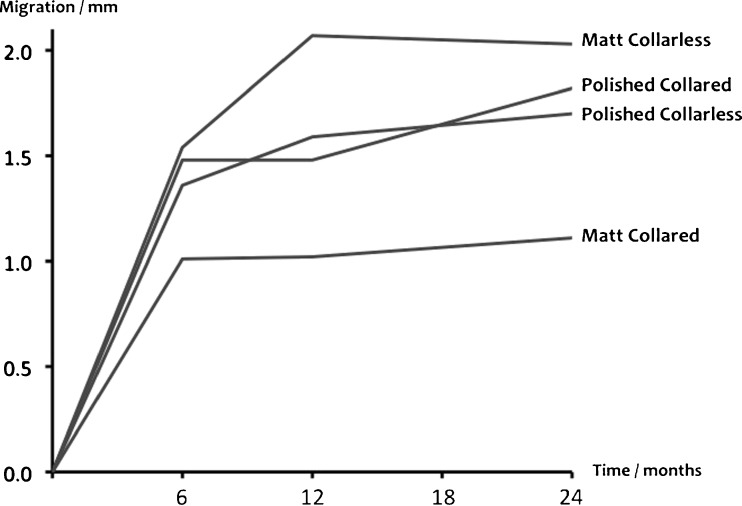

Subsidence at two years of individual stems in each group is shown in Fig. 3. There was a trend for the collared matt stems to migrate less than other groups, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.18). In all groups, the majority of subsidence happened in the first six months, and all stems were stable between 12 and 24 months (Fig. 4). There was no correlation between the level of subsidence of individual stems and eventual failure or loosening.

Fig. 3.

Individual subsidence of stems within groups at 2 years

Fig. 4.

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) scores at latest follow-up

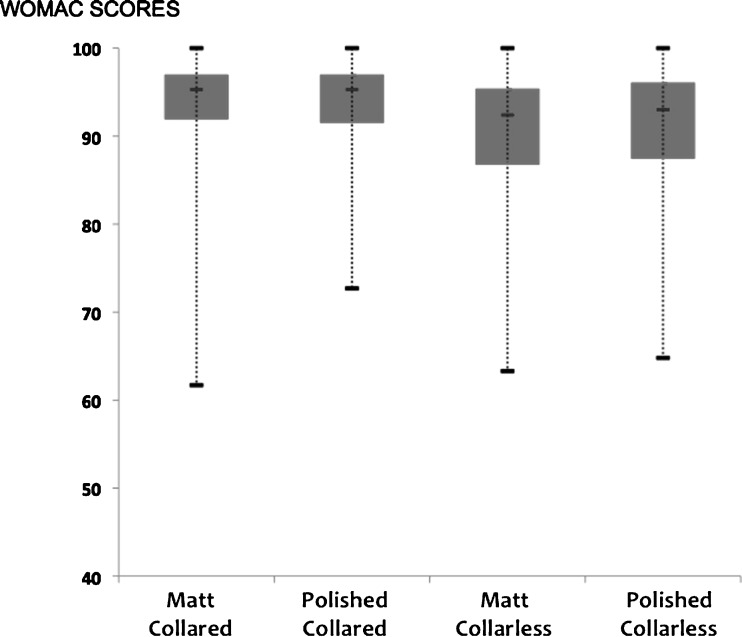

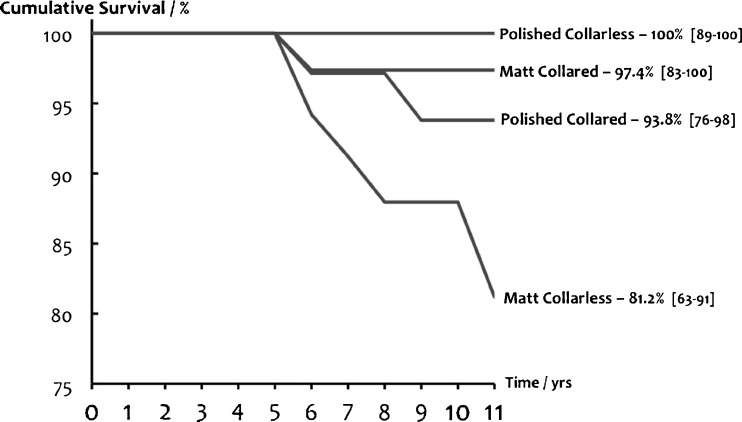

There were no significant differences in WOMAC scores between groups for the surviving stems (p = 0.29) (Fig. 5). The mean for the entire cohort was 91. Survival curves with cumulative survival at 11 years and 95 % CI (Fig. 6) were: polished collarless 100 % (89–100 %), matt collared 97.4 % (85–100 %), polished collared 93.8 % (80–98 %) and matt collarless 81.2 % (63–91 %). The only statistically significant difference was between the two collarless stems, with the matt surface leading to an inferior outcome, (p = 0.02).

Fig. 5.

Mean stem subsidence in each group over 2 years

Fig. 6.

Survival curves showing cumulative survival at 11 years, with 95 % confidence intervals

Discussion

The two most commonly used stems in the Swedish Arthroplasty Register are the Lubinus Sp II, (Waldemar Link, Hamburg, Germany), a collared, CoCr, matt-surface stem; and the Exeter (Stryker, NJ, USA), a tapered, highly polished, collarless stem made of stainless steel. Both designs show excellent long-term clinical survival [17]. Individual series show excellent clinical results with collared polished [1], collared matt [18], collarless polished [19] and collarless matt [20] stems, which indicates that the two features we assessed in this study are only two of many that could affect long-term survival. Other studies concentrated on the effect of surface finish and presence of a collar. Lachiewicz et al. reported on a prospective randomised trial of a collared, precoated stem and a collarless, polished stem and found no difference in survival at a mean of six years [21]. Vaughn et al. compared a collared, satin-finish stem with a morphologically identical precoated stem and found that the latter performed worse at four years of follow-up [22]. Vail et al. compared a polished, collared stem with a grit-blasted stem and found no revisions or difference in radiographic loosening at five years, which led them to conclude that the surface finish may be secondary in importance to optimal stem design and good cement technique for short-term success [23]. The same grit-blasted, collared stem was compared in a study by Sherfey et al. with a polished, collarless stem and found to have significantly worse results of 67 % survival at five years [24]. A case–control study comparing collared stems with satin or rough finishes showed increased levels of radiographic failure with the latter type at between four and eight years [25]. Other, less powerful, studies comparing stem finish also found worse outcomes for stems with increasing degrees of surface roughness [8, 26–28].

Two prospective randomised studies compared stems with and without a collar. One trial with published data at both five and ten years found no difference in outcomes between a collared or collarless matt CoCr stem [13, 29]. In that study, there were no revisions in those stems defined as having good collar to bone contact, although this was only achieved in 47 % of cases. Meding et al. compared a collared and collarless titanium stem and found no differences in clinical outcomes at six years [30]. Whereas the variability of these studies does not allow any firm conclusions, it would appear that roughening the surface of the stem to increase cement bonding does not confer a survival benefit. However, implantation of roughened stems may be more unforgiving once a cycle of loosening is initiated due to the increased wear debris produced. Grose et al. reported high early failure rates with a modified design of a previously well-performing stem. The addition of an extra roughened proximal coating resulted in debonding, leading to accelerated osteolysis and loosening. [31].

There are limitations to our study. The sample size would only be able to detect large variations in survival between groups [21]. In addition, we were unable to follow-up all patients with evaluation of clinical outcomes and radiology. Although all patients contacted had good WOMAC scores, they might include some patients with early subclinical loosening.

This paper reports the medium-term results of a prospective randomised trial designed to investigate the effect of a collar and altered surface finish on the survival of cemented femoral stems of the same profile and material. Overall survival of all stems in our study was 93 % (95 % CI 87–97 %). In the presence of a collar, the surface finish of the cemented femoral stem in this study did not significantly affect survivorship or function. Without a collar, a matt finish was associated with a lower survivorship of 81 % at 11 years. Collared matt stems and collarless polished stems gave equivalent excellent results.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William Twyman for his assistance with digitising and analysis of radiographs.

Conflicts of Interest and Funding

Johnson and Johnson (now Depuy, IN, USA) provided funding for the implants used in the study and for a research nurse over a 2-year period. None of the authors have any other financial disclosures relevant to this study.

Appendix

Fig. 7.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram

References

- 1.Mulroy RD, Harris WH. The effect of improved cementing techniques on component loosening in total hip replacement. An 11-year radiographic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:757–760. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B5.2211749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrack RL. Early failure of modern cemented stems. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:1036–1050. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.16498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen G. Femoral stem fixation. An engineering interpretation of the long-term outcome of Charnley and Exeter stems. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:754–756. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B5.8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheerlinck T, Casteleyn P-P. The design features of cemented femoral hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1409–1418. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B11.17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohler CG, Callaghan JJ, Collis DK, Johnston RC. Early loosening of the femoral component at the cement-prosthesis interface after total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1315–1322. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jewett BA, Collis DK. Radiographic failure patterns of polished cemented stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:132–136. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000246540.64821.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anthony PP, Gie GA, Howie CR, Ling RS. Localised endosteal bone lysis in relation to the femoral components of cemented total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:971–979. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howie DW, Middleton RG, Costi K. Loosening of matt and polished cemented femoral stems. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:573–576. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B4.8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong KS. The biomechanical role of the collar of the femoral component of a hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:664–665. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2380224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowninshield RD, Brand RA, Johnston RC, Pedersen DR (1981) An analysis of collar function and the use of titanium in femoral prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res 270–277 [PubMed]

- 11.Lewis JL, Askew MJ, Wixson RL, et al. The influence of prosthetic stem stiffness and of a calcar collar on stresses in the proximal end of the femur with a cemented femoral component. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markolf KL, Amstutz HC, Hirschowitz DL. The effect of calcar contact on femoral component micromovement. A mechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:1315–1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Settecerri JJ, Kelley SS, Rand JA, Fitzgerald RH (2002) Collar versus collarless cemented HD-II femoral prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res 146–152 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC (1979) “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 17–27 [PubMed]

- 15.Rothman KJ. Estimation of confidence limits for the cumulative probability of survival in life table analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:557–560. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray DW, Carr AJ, Bulstrode C. Survival analysis of joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:697–704. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kärrholm J, Garellick G, Herberts P (2008) Annual Report 2008: Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. http://www.secca.es/registros/AnnualReport-2008-eng.pdf. Accessed 21 July 2013

- 18.Issack PS, Botero HG, Hiebert RN, et al. Sixteen-year follow-up of the cemented spectron femoral stem for hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:925–930. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00336-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yates PJ, Burston BJ, Whitley E, Bannister GC. Collarless polished tapered stem: clinical and radiological results at a minimum of ten years’ follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90-B:16–22. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B1.19546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berli BJ, Schäfer D, Morscher EW. Ten-year survival of the MS-30 matt-surfaced cemented stem. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:928–933. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.16149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachiewicz PF, Kelley SS, Soileau ES. Survival of polished compared with precoated roughened cemented femoral components. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1457–1463. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaughn BK, Fuller E, Peterson R, Capps SG. Influence of surface finish in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:110–115. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vail TP, Goetz D, Tanzer M, et al. A prospective randomized trial of cemented femoral components with polished versus grit-blasted surface finish and identical stem geometry. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:95–102. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherfey JJ, McCalden RW. Mid-term results of Exeter vs Endurance cemented stems. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:1118–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Della Valle AG, Zoppi A, Peterson MGE, Salvati EA (2005) A rough surface finish adversely affects the survivorship of a cemented femoral stem. Clin Orthop Relat Res 158–163 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Collis DK, Mohler CG. Comparison of clinical outcomes in total hip arthroplasty using rough and polished cemented stems with essentially the same geometry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:586–592. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamadouche M, Baqué F, Lefevre N, Kerboull M. Minimum 10-year survival of Kerboull cemented stems according to surface finish. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:332–339. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez Della Valle A, Comba F, Zoppi A, Salvati EA. Favourable mid-term results of the VerSys CT polished cemented femoral stem for total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2006;30:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley SS, Fitzgerald RH, Rand JA, Ilstrup DM (1993) A prospective randomized study of a collar versus a collarless femoral prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 114–122 [PubMed]

- 30.Meding JB, Ritter MA, Keating EM, et al. A comparison of collared and collarless femoral components in primary cemented total hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grose A, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Bullough P, et al. High failure rate of a modern, proximally roughened, cemented stem for total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2006;30:243–247. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]