Abstract

Rationale

Sorafenib is an effective treatment for renal cell carcinoma, but recent clinical reports have documented its cardiotoxicity through an unknown mechanism.

Objective

Determining the mechanism of sorafenib-mediated cardiotoxicity.

Methods and Results

Mice treated with sorafenib or vehicle for 3 weeks underwent induced myocardial infarction (MI) after 1 week of treatment. Sorafenib markedly decreased 2-week survival relative to vehicle-treated controls but echocardiography at 1 and 2 weeks post-MI detected no differences in cardiac function. Sorafenib-treated hearts had significantly smaller diastolic and systolic volumes and reduced heart weights. High doses of sorafenib induced necrotic death of isolated myocytes in vitro, but lower doses did not induce myocyte death or affect inotropy. Histological analysis documented increased myocyte cross-sectional area despite smaller heart sizes following sorafenib treatment, further suggesting myocyte loss. Sorafenib caused apoptotic cell death of cardiac- and bone-derived c-kit+ stem cells in vitro and decreased the number of BrdU+ myocytes detected at the infarct border zone in fixed tissues. Sorafenib had no effect on infarct size, fibrosis or post-MI neovascularization. When sorafenib-treated animals received metoprolol treatment post-MI, the sorafenib-induced increase in post MI mortality was eliminated, cardiac function was improved, and myocyte loss was ameliorated.

Conclusions

Sorafenib cardiotoxicity results from myocyte necrosis rather than from any direct effect on myocyte function. Surviving myocytes undergo pathological hypertrophy. Inhibition of c-kit+ stem cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis exacerbates damage by decreasing endogenous cardiac repair. In the setting of MI, which also causes large-scale cell loss, sorafenib cardiotoxicity dramatically increases mortality.

Keywords: Sorafenib, stem cell, cardiotoxicity, metoprolol, drug, myocardial infarction, cell death, myocyte apoptosis and necrosis, kinase inhibitors, cell loss

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinase inhibitors (KIs) predominantly targeting mutated tyrosine kinases (but also serine/threonine kinases) have revolutionized cancer therapy over the last decade.1 Several malignancies that were formerly fatal are now more manageable chronic diseases thanks to these agents. However, several KIs have been associated with significant cardiovascular toxicities including contractile dysfunction and heart failure as well as vascular events.2, 3 Added to this, patients receiving KIs are living to older ages, further increasing risk of cardiovascular complications. This has led to the creation and expansion of the field of “cardio-oncology”.2

The most problematic agents to date are the so-called VEGF signaling pathway inhibitors. These agents are associated with hypertension that can be severe in some patients.4 The approved agents include axitinib, pazopanib, regorafenib, sunitinib, sorafenib, and vandetanib, and others are under development. These agents tend to be poorly selective, inhibiting a number of kinases that play no role in malignancies. Sunitinib was the first of this group shown to cause left ventricle (LV) dysfunction and heart failure in patients.5, 6 However, molecular mechanisms were difficult to fully identify due to the poor selectivity of this drug. Another popular agent is sorafenib (Nexavar, Bayer; Leverkusen, Germany), so named because it targets (among other kinases) the serine/threonine kinase RAF and the related B-RAF.7 These kinases are implicated in a number of malignancies including renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and melanoma. Several groups have been unable to identify the mechanisms of sorafenib cardiotoxicity. The goal of the present study was to determine the bases of this cardiotoxicity and potentially remedy it, not just for sorafenib but for other problematic agents as well.

Sorafenib gained FDA approval for treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in 2005.7 RCC is a hypervascularized solid tumor characterized by constitutive activation of the canonical MAP-kinase (MAPK) pathway leading to uncontrolled cell growth.8 Increased VEGF expression by RCC tumors is an indicator of poor prognosis, because VEGF expression leads to stimulation of angiogenesis that supports uncontrolled growth and proliferation of the tumor.9 Sorafenib has known antagonism against B-RAF and RAF1 (early kinases in the MAPK cascade10) as well as against VEGF receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), making it particularly well-suited for the treatment of RCC.2, 7 Sorafenib is also known to inhibit c-kit, a receptor that is upregulated in other cancers such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors.11 The c-kit receptor is also expressed normally on cardiogenic stem cells found in the heart,12, 13 cortical bone,14 and bone marrow15, 16, and it is expressed on other progenitor cells found in the lungs17 and kidneys.18 Flt-3, which is also upregulated in acute leukemias,19, 20 and RET, which is upregulated in multiple endocrine neoplasia and papillary thyroid carcinoma,21 are two other receptors that are known targets of sorafenib.7

In the first randomized, controlled, phase III clinical trial of sorafenib for treatment of RCC, a significant increase in cardiac ischemia was reported in the sorafenib treatment arm versus placebo (2.7 v. 0.04%, p = 0.01).22 Interestingly, the occurrence of symptoms related to heart failure was not significantly different between the placebo and treatment arms of this study (2% of patients in each group reported dyspnea). This is consistent with the inadequacy of patient self-reporting as a means to detect cardiotoxicity and it may explain why earlier phase I and II trials of the drug failed to detect new onset heart disease, since few of these studies examined cardiac function and largely relied instead on reporting of symptoms.23-27

Most of these phase I/II studies excluded patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease or heart failure.23-27 In contrast to imatinib-induced cardiotoxicity, phase III clinical trials have suggested that sorafenib cardiotoxicity may not be as closely related to a previous history of underlying heart disease. In the most comprehensive clinical study to examine the cardiotoxic effects of sorafenib and another multikinase inhibitor, sunitinib, 86 patients underwent baseline measurements of creatinine-kinase (CK), CK-MB, troponin T (TnT), ECG, blood pressure measurement, evaluation of cardiac symptoms (dyspnea on exertion, angina, dizziness) and cardiac risk factors.28 A total of 14 patients on sorafenib developed cardiac abnormalities within a median of 8 weeks after starting therapy: 11 had CK-MB elevation, 3 had TnT elevation, and 3 had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measured by echocardiography at the time of event. Interestingly, only one of these patients had a history of pre-existing cardiac disease (first degree AV block) at baseline, although 9/14 patients had preexisting risk factors for coronary artery disease.28 A more recent case report described a patient with no history of heart disease who developed a dilated cardiomyopathy with reduced LVEF that was reversible after discontinuation of sorafenib therapy for 3 months.29 There have also been four published case reports describing the occurrence of acute coronary artery disease secondary to coronary vasospasm in patients on sorafenib therapy.30-33

The mechanisms underlying KI-related cardiac injury remains unclear. In this study, we show that sorafenib enhances mortality in a mouse model of myocardial infarction (MI). Studies were then performed in various myocardial cell types including myocytes, stem cells and fibroblasts, to determine the mechanism of the sorafenib-mediated post MI mortality. Sorafenib treatment was shown to induce myocyte death through necrosis both in vitro and in vivo. Myocytes in sorafenib-treated hearts had significant pathologic hypertrophy. The cardiogenic stem cell pool in both the heart and bones were potently inhibited by sorafenib, which may diminish cardiac repair after MI-induced damage. Sorafenib did not alter post-MI fibrosis or neovascularization. When sorafenib-treated mice received the selective β1-adrenergic antagonist metoprolol post-MI, the sorafenib-induced increase in post MI mortality was eliminated, cardiac function was improved, and myocyte loss was ameliorated. These results suggest that sorafenib promotes myocyte death, and after MI the enhanced sympathetic activity needed to maintain cardiac function exacerbates this myocyte death phenotype. Our results suggest that cancer patients undergoing therapy with sorafenib and at risk of cardiovascular complications might benefit from prophylactic therapy with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists.

METHODS

Sorafenib and Metoprolol dosing

For all in vivo experiments, doses of 30 mg/kg/d sorafenib were used based on preclinical mouse models that demonstrated efficacy of this dose at inhibiting cancer growth in mouse models. Preclinical trials showed that doses of 30 mg/kg/d in mice effectively reduced the proliferation of VEGF-dependent tumors in mice.34, 35 This dose blocked growth and proliferation of both RCC 36 and HCC tumors 37 in vivo in mouse models. Doses below 30 mg/kg/d were not effective at inhibiting tumor growth in the same mouse models.36 In humans, phase II and III clinical trials have demonstrated that 400 mg twice daily (800 mg/d) is the most effective dose for these same malignancies (HCC and RCC), and this dose achieves a plasma concentration of 2-6 gm/L 38 or about 1-3 mM 39. Plasma levels of sorafenib were attained by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry 40. These same clinical trials have also reported cardiotoxicity at this same dose. For our in vitro experiments, 0.1-50 uM sorafenib was used. These in vitro doses encompass the range of those used in preclinical studies during the development of sorafenib.34 For in vivo metoprolol dosing, animals received 20 mg/kg/d metoprolol tartrate (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). This is a similar IP dose of metoprolol that has been used in previously published mouse models to affect airway reactivity41 and reduce post-MI LV dysfunction in a mouse MI model.42

Please refer to the Supplemental Materials and Methods section for additional experimental methods.

RESULTS

Sorafenib treatment increased post-MI mortality and reduced heart size but did not affect cardiac function

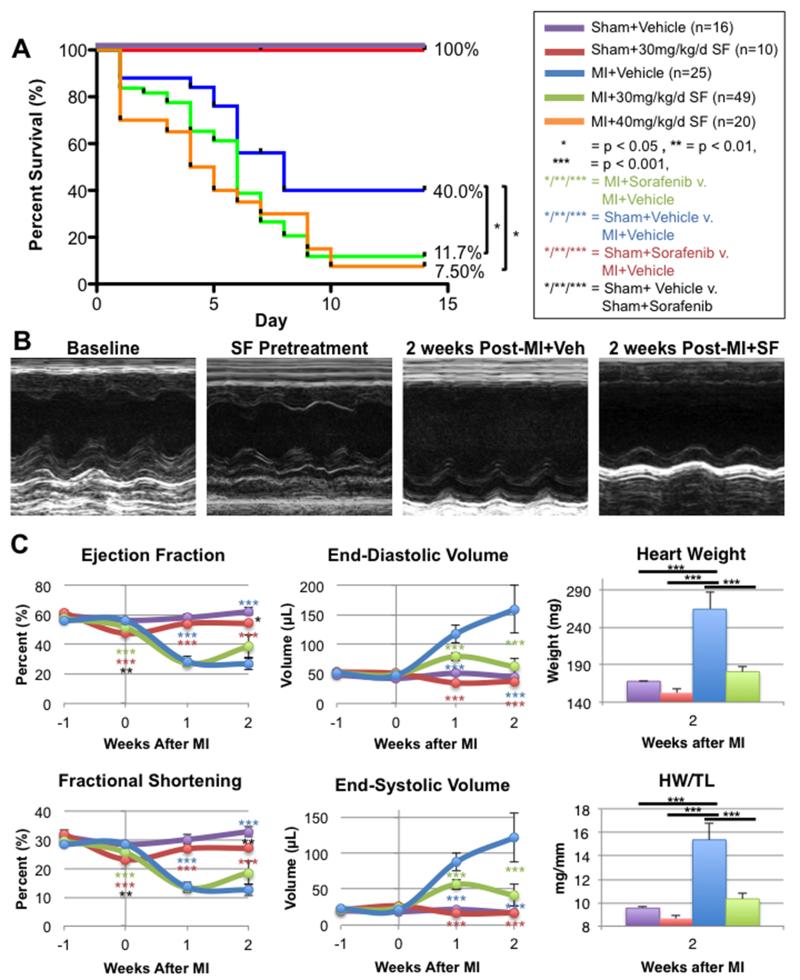

Mice underwent sham-operation with vehicle (n=16) or 30 mg/kg/day IP sorafenib (n=10), or animals underwent induced MI with vehicle (n=25), 30 mg/kg/day (n=49) or 40 mg/kg/day (n=20) IP sorafenib dosing. All animals underwent baseline echocardiography prior to dosing, and then each received vehicle or sorafenib for a total duration of 3 weeks. After the first week of dosing, surgery was performed and the remaining animals continued to receive vehicle or sorafenib for 2 more weeks or until death or sacrifice (Figure 1A). Both sham groups (with vehicle or sorafenib dosing) demonstrated 100% two-week survival, while the MI+Vehicle control group had 40.0% two-week survival. A log-rank test of the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that sorafenib treatment at the low and high doses significantly reduced survival to 11.7% (p < 0.01) and 7.5% (p < 0.01), respectively relative to vehicle-treated MI controls.

Figure 1. Post-MI survival and cardiac function.

A) Survival of mice 2 weeks after MI with 1 week of sorafenib (SF) or vehicle (Veh) pretreatment. B) Representative M-mode echocardiograms of mice at baseline (prior to SF treatment), after 1 week of SF pretreatment, or 2 weeks after MI with Veh or SF treatment. C) Cardiac function and volumes measured by echocardiography and gross heart weight (HW) and HW/tibia length measured after sacrifice.

Representative echocardiograms taken at baseline, after 1 week of sorafenib treatment (prior to surgery) and two weeks post-MI+Vehicle or post-MI+Sorafenib are displayed in Figure 1B. Mean cardiac function, volumes, and gross heart weight (HW) and heart weight/tibia length (HW/TL) are displayed in Figure 1C. Sorafenib treatment had little effect on cardiac function. After 1 week of sorafenib treatment (before any surgery was performed), both left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and fractional shortening (FS) were slightly diminished in sorafenib-treated animals relative to vehicle-treated controls. Additionally, the sham-operated group receiving sorafenib dosing continued to have slightly depressed LVEF and FS relative to the vehicle-treated sham group at 1 and 2 weeks after surgery. None of these effects reached statistical significance. In addition, at 1 or 2 weeks after surgery, there were no significant alterations in cardiac function measured by transthoracic echocardiography in the MI+Vehicle and MI+Sorafenib groups.

The most significant differences between the sorafenib and vehicle-treated groups were in the cardiac volumes and gross heart weights. Animals treated with sorafenib had significantly smaller hearts (Figure 1C). End-diastolic and end-systolic volumes in MI+Sorafenib hearts were significantly smaller at 1 and 2 weeks post-MI versus MI+Vehicle controls. After two weeks their volumes were so much smaller that they were not significantly greater from those in the sham-operated groups. Similar patterns were observed when examining gross heart weight (HW) and heart weight normalized to tibia length (HW/TL). The MI+Vehicle control group had increased heart weights by 2 weeks post-MI consistent with post-MI cardiac remodeling with pathological hypertrophy. These changes were not observed in the MI+Sorafenib group. In fact, MI+Sorafenib mice were not significantly different from Sham+Vehicle controls. Interestingly, when examining HW and HW/TL, Sham+Sorafenib animals had smaller heart weights than both the MI+Sorafenib and Sham+Vehicle groups. These data suggest that sorafenib had little or no direct effect on myocyte function. However, sorafenib decreased heart size both in the presence and absence of MI injury.

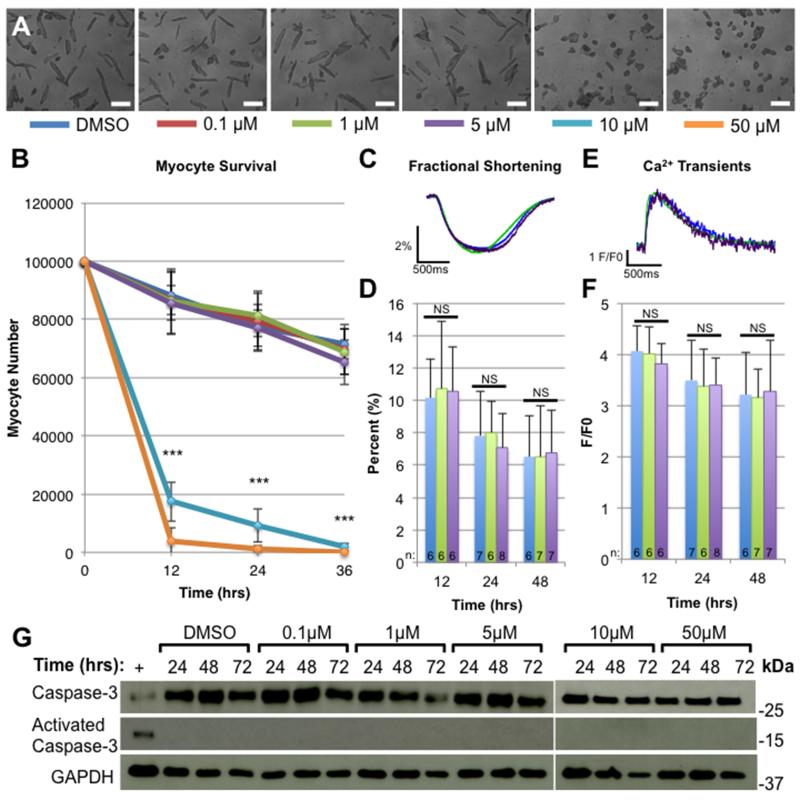

Sorafenib induces myocyte necrosis at high doses and does not affect inotropy of isolated myocytes in vitro

Sorafenib had little or no effect on baseline cardiac function in vivo. However, regulatory factors controlling overall cardiac pump function could have masked direct negative inotropic effects of sorafenib on myocyte contractile function. To test for this possibility, adult feline left ventricular myocytes were isolated and exposed to 0.1-50 μM sorafenib or DMSO (control). Myocytes were cultured for 72 hours in the presence of the drug, and their survival and contractile function was measured. Figure 2A shows representative brightfield micrographs taken after 72 hours of exposure to sorafenib, and Figure 2B demonstrates survival of myocytes over the first 36 hours in culture. At low concentrations (0.1-5 μM), sorafenib had no effect on myocyte survival, but at the higher concentrations (10-50 μM) sorafenib induced complete myocyte necrosis within the first 12 hours in vitro. Because of the potent necrotic effect observed above 10 μM, cell physiology could only be studied at the lower doses. There were no significant differences in fractional shortening (Figure 2C-D) or peak systolic Ca2+ (Figure 2E-F) between the DMSO-treated cells (control) or cells treated with 1 or 5 μM sorafenib over 48 hours. These studies show that high doses of sorafenib can induce myocyte necrosis, while there were no significant effects of lower doses on myocyte survival or inotropy.

Figure 2. Effects of sorafenib on isolated myocytes in vitro.

Feline left ventricular myocytes were isolated and cultured in the presence of DMSO (control) or 0.1-50 μM sorafenib for 48 hours. A) Bright field micrographs of myocyte cultures 36 hours after treatment with sorafenib at each dose. Scale bars = 100 μm. B) Myocyte counts after 12, 24, or 36 hours of exposure to each sorafenib dose (n=3). ANOVA was used to measure the difference between samples at each time point. Samples treated with 10-50 uM had significantly fewer myocytes at all time points, *** = p < 0.001. Fractional shortening (FS) traces (C), average FS data (D), calcium transients (E) and peak calcium transient measurements (F) of isolated myocytes treated with DMSO, 1 or 5 uM sorafenib for 12, 24, or 48 hours. ANOVA was performed to detect statistical difference between samples, NS = no significant difference (p > 0.05). G) Western analysis measuring total caspase-3 or activated caspase-3 in lysates from myocytes treated with sorafenib for 24, 48 or 72 hours. Positive control (+) = lysates from myocytes treated with 100μM H2O2.

Myocyte lysates collected 24, 48, or 72 hours after exposure to sorafenib at each dose were used for Western analysis of caspase-3 (Figure 2G), a molecule known to be associated with activation of the apoptotic cell death pathways.43 No activation of caspase-3 at any time-point or at any dose of sorafenib was found. A positive control (+) was included in which caspase-3 was activated in isolated myocytes by exposure to 100 μM H2O2. Thus, the cell death observed with sorafenib doses above 10 μM appears to be due to necrotic cell death rather than via apoptosis.

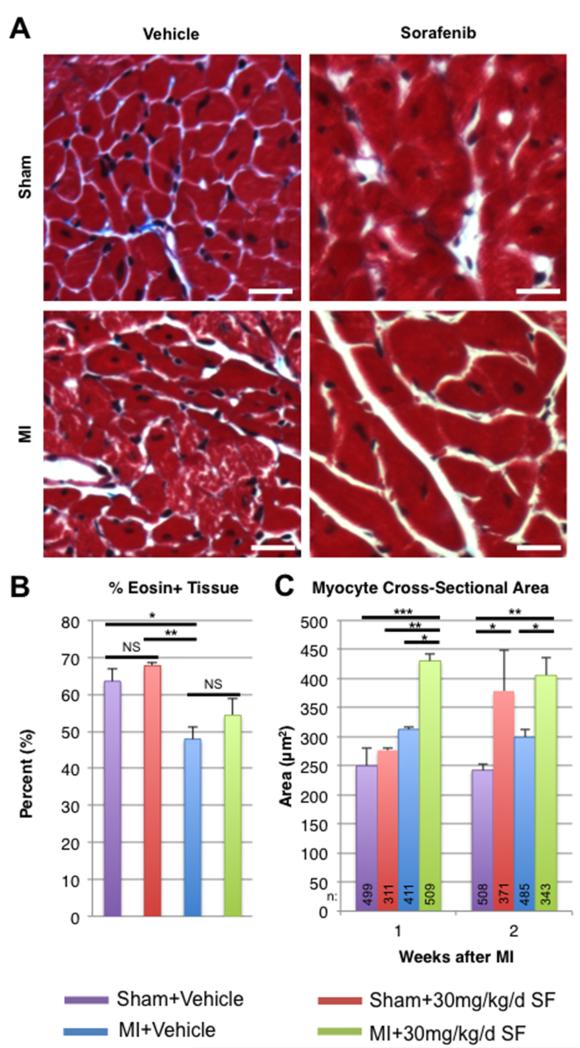

Decreased heart size observed with sorafenib treatment occurs secondary to myocyte death, with surviving myocytes undergoing pathologic hypertrophy

In isolated myocytes in vitro, sorafenib treatment clearly induces necrotic cell death but does not appear to effect contractile function of surviving myocytes. In order to examine the effects of sorafenib on myocytes in vivo, myocyte size and general tissue distribution were measured using tissue sections from hearts fixed at 1 or 2 weeks post-MI. Representative brightfield micrographs from hearts fixed 2 weeks after surgery and stained with Masson’s trichrome are displayed in Figure 3A. BioQuant was then performed to determine whether there was any difference between groups in the fraction of eosin+ (red) myocardial tissue out of total myocardial tissue (Figure 3B). There was a decline in the percent of myocyte volume fraction following MI surgery in both sorafenib- and vehicle-treated groups. There was no significant difference in myocyte volume fraction between sorafenib-treated and vehicle-treated animals between either the sham-operated or MI groups, even though sorafenib treatment was associated with decreased heart size measured both grossly and by echocardiography.

Figure 3. Effects of sorafenib on myocytes in vivo in the infarcted mouse heart.

Tissue sections from hearts fixed at 1 or 2 weeks post-MI were stained with Masson’s trichrome. A) Representative bright field micrographs from sham-operated or MI animals treated with vehicle or sorafenib two weeks after surgery. Scale bars = 20 μM. B) Percent of eosin+ myocardial tissue determined by BioQuant analysis 2 weeks post-MI. C) Average myocyte cross-sectional area. ANOVA was used to determine statistical differences between samples: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Myocyte cross-sectional area was measured in each group (Figure 3C), and over 3400 myocytes were analyzed from 40 animals. MI alone resulted in small increases in myocyte cross-sectional area, consistent with post-MI hypertrophy. Interestingly, sorafenib treatment in sham animals also resulted in increased myocyte cross-sectional area, even though overall heart size was significantly smaller than in vehicle-treated controls. Sham+Sorafenib myocytes had significantly greater cross-sectional areas than vehicle-treated sham controls, and MI+Sorafenib animals had significantly greater myocyte cross-sectional areas than vehicle-treated MI controls. The combination of MI and sorafenib treatment resulted in the largest myocyte cross-sectional areas of all the groups (400-450 μm2). The most likely mechanism by which sorafenib could increase individual myocyte size while decreasing overall heart weight would be if a significant number of myocytes were lost. We found that sorafenib causes myocyte necrosis at high doses in vitro (Figure 2), and this is the likely mechanism for the loss of myocyte mass in vivo. These results suggest that sorafenib induces myocyte death and the remaining myocytes undergo pathologic hypertrophy, so the percentage of muscle tissue/total myocardium is not different between sorafenib and vehicle treated groups (in either sham or MI groups).

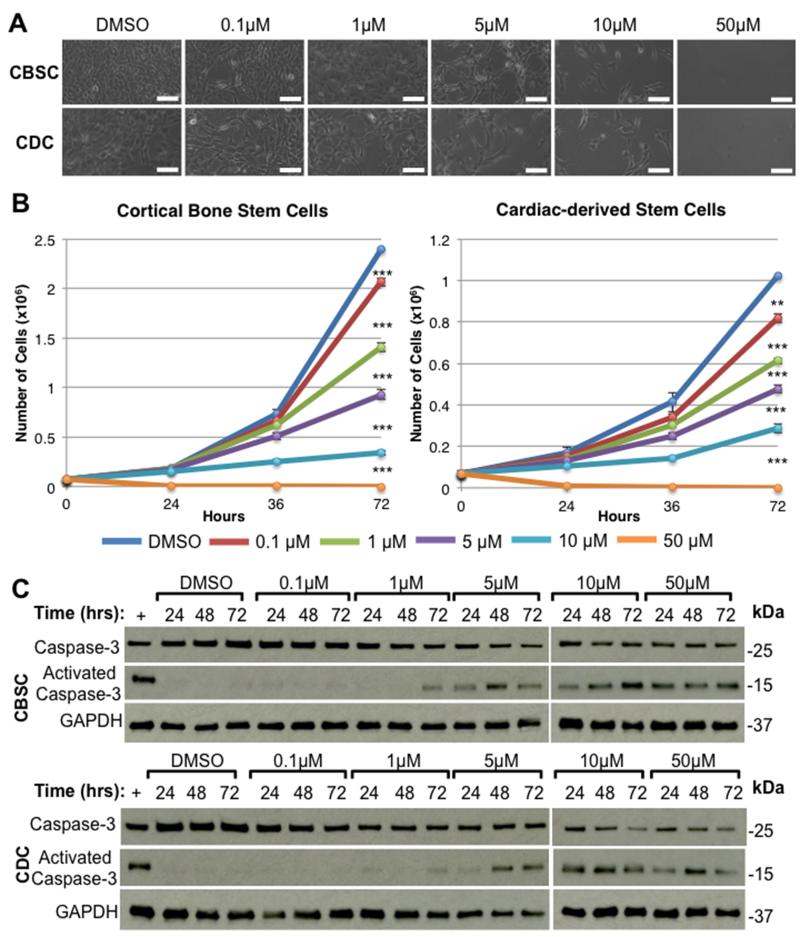

Sorafenib inhibits stem cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo

Recent data 44 suggests that myocytes that die when the heart is subjected to toxic agents can be replaced by the generation of new cardiac myocytes derived from a cKit+ progenitor cell pool. Sorafenib is known to inhibit the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor,2, 7 a receptor that is found on cardiogenic stem cells located in the heart12, 13, 45 and bone.14 Thus, sorafenib may exert some inhibitory effect on these cell populations, which could also contribute to the high post-MI mortality observed with sorafenib treatment. Figure 4A shows cultures of isolated cortical bone-derived stem cells (CBSCs) or cardiac-derived stem cells (CDCs) after 72 hours of exposure to DMSO (control) or 0.1-50 μM sorafenib. CBSCs and CDCs were plated at low densities (75,000 cells/well) and were allowed to proliferate to confluency over 72 hours. Both stem cell populations rapidly proliferate in culture. Cell counts were performed at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Growth curves show a potent time- and dose-dependent inhibition of stem cell proliferation after exposure to sorafenib (Figure 4B), and this is reflected in the bright field images (Figure 4A). Western analysis of total vs. activated caspase-3 was performed on cell lysates prepared at each time point to determine whether this cell death was due to activation of apoptosis. We found a time- and dose-dependent activation of caspase-3 with corresponding degradation of total caspase-3 signal (Figure 4C). These data suggest that sorafenib inhibits stem cell proliferation and induces stem cell apoptosis. It is possible that stem cells were lost from culture via apoptosis without an effect of sorafenib on stem cell proliferation. However, cultures exposed to high doses of sorafenib (>10 μM) failed to undergo any increase in cell number, suggesting inhibition of stem cell proliferation and stem cell apoptosis are occurring simultaneously. These results suggest that sorafenib may inhibit endogenous cardiac repair by modifying the behavior of cKit+ cardiac progenitor cells.

Figure 4. Effects of sorafenib on stem cells in vitro.

Cortical bone (CBSC) or cardiac-derived (CDC) stem cells were allowed to proliferate to confluency over 72 hours in the presence of DMSO (control) or 0.1-50 uM sorafenib. A) Bright field micrographs of CBSCs or CDCs after 72 hours in culture with sorafenib. Scale bars = 100 μm. B) Mean cell counts at 24, 48, and 72 hours after plating (n=3). ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 C) Western analysis of stem cell lysates showing total or activated caspase-3. Positive control (+) = lysates from stem cells treated with 100μM H2O2.

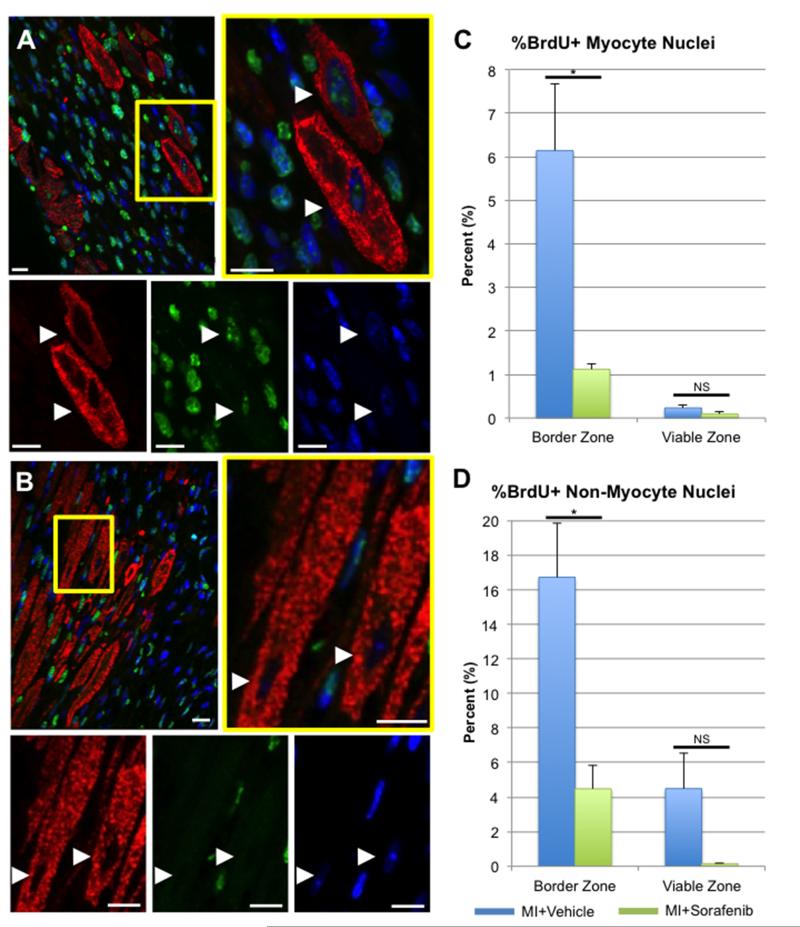

To assess whether sorafenib treatment inhibited stem cell function in vivo, a BrdU pulse-labeling strategy was used to identify myocytes and non-myocytes undergoing S-phase DNA replication post-MI. This strategy has been previously used by our group to identify newly-generated myocytes in the feline heart after ischemic insult secondary to catecholamine overload,46 and other groups have used similar strategies to measure newly-generated myocytes in the adult mouse heart at baseline47 or after MI.12, 16, 48, 49 Figure 5 shows representative confocal micrographs from the infarct border zone of hearts treated with vehicle (Figure 5A) or sorafenib (Figure 5B) 1 week after MI and BrdU labeling. Quantitative histology showing the percentage of BrdU+ myocytes (Figure 5C) or non-myocytes (Figure 5D) demonstrates that sorafenib-treatment significantly decreases the percentage of both myocyte and non-myocyte nuclei that are brightly labeled with BrdU after 1-week post-MI in the infarct border zone, while no significant difference was seen in viable zones. These findings are consistent with the in vitro data in Figure 4, suggesting that sorafenib treatment potently inhibits post-MI stem cell function in vivo.

Figure 5. Sorafenib treatment decreases BrdU labeling of nuclei at the infarct border zone.

Confocal micrographs of vehicle-(A) or sorafenib-treated (B) hearts at 1 week post-MI that were immunostained against α-sarcomeric actin (red), BrdU (green) and nuclei labeled with DAPI (blue). White arrowheads = myocyte nuclei. Scale bars = 20μm. The percentage of myocyte (C) or non-myocyte nuclei (D) that were brightly-labeled with BrdU at the infarct border zone or in distant viable regions were quantified. Statistical difference between groups was determined by 1-way ANOVA. * = p < 0.05, NS = Not Significant (p > 0.05).

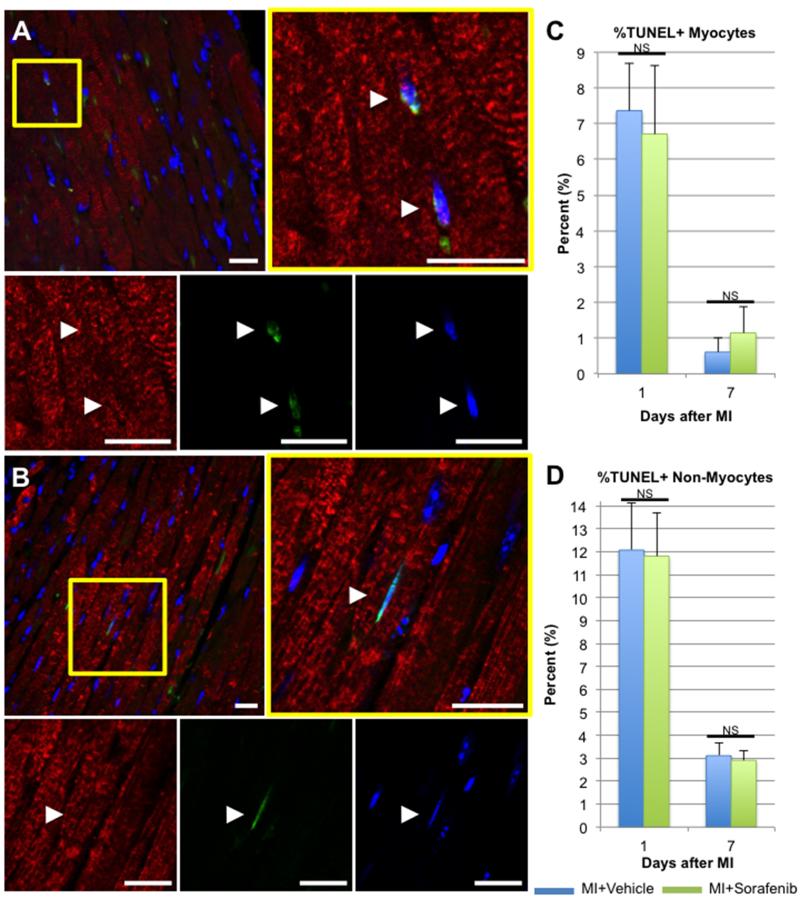

Sorafenib-mediated myocyte loss is not caused by apoptosis in vivo

Sorafenib treatment had little effect on apoptosis of cardiac myocytes or non-myocytes near the infarct border zone or in distant viable myocardium. To quantify the percent of myocytes and non-myocytes undergoing apoptosis post-MI, TUNEL staining was performed on myocardial tissues fixed at 1 or 7 days post-MI. Figure 6A displays a representative confocal micrograph of a vehicle-treated heart 1 day after MI, with the magnified panel showing a binucleated myocyte with two TUNEL+ nuclei and an adjacent TUNEL+ non-myocyte nucleus. Figure 6B depicts the border zone of a sorafenib-treated heart 1 day after MI, with a TUNEL+ myocyte nucleus magnified at right. MI injury alone is known to acutely increase myocyte apoptosis at the infarct border zone in rodents50, 51 as well as humans52, but sorafenib-treated tissues did not have a significantly greater percentage of TUNEL+ myocyte nuclei than vehicle treated controls at 1 or 7 days post-MI. Likewise, there was no significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL+ non-myocyte nuclei detected at the infarct border zone at 1 or 7 days post-MI. Similar analyses were performed on distant viable myocardium > 1000 μm from the border zone, and this also demonstrated no significant increase in the number of TUNEL+ myocyte or non-myocyte nuclei detected in sorafenib-treated hearts after 1 or 7 days post-MI compared to vehicle-treated controls (data not shown). These data support the in vitro findings in Figure 2, which suggest that myocytes are lost primarily by necrosis and not apoptosis.

Figure 6. Apoptosis of cardiac myocytes and non-myocytes at the infarct border zone was not increased by sorafenib treatment.

Tissue sections from hearts fixed at 1 or 7 days post-MI were immunostained for TUNEL (green) and tropomyosin (red), and nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 25 μM. Representative confocal micrographs from hearts fixed 1 day after MI with vehicle (A) or sorafenib treatment (B) are displayed. White arrowheads = TUNEL+ myocyte nuclei. The percentages of TUNEL+ myocyte (C) or non-myocyte nuclei (D) at the infarct border zone were quantified at each time point. Significant difference between groups was determined using 1-way ANOVA. NS = Not Significant (p > 0.05)

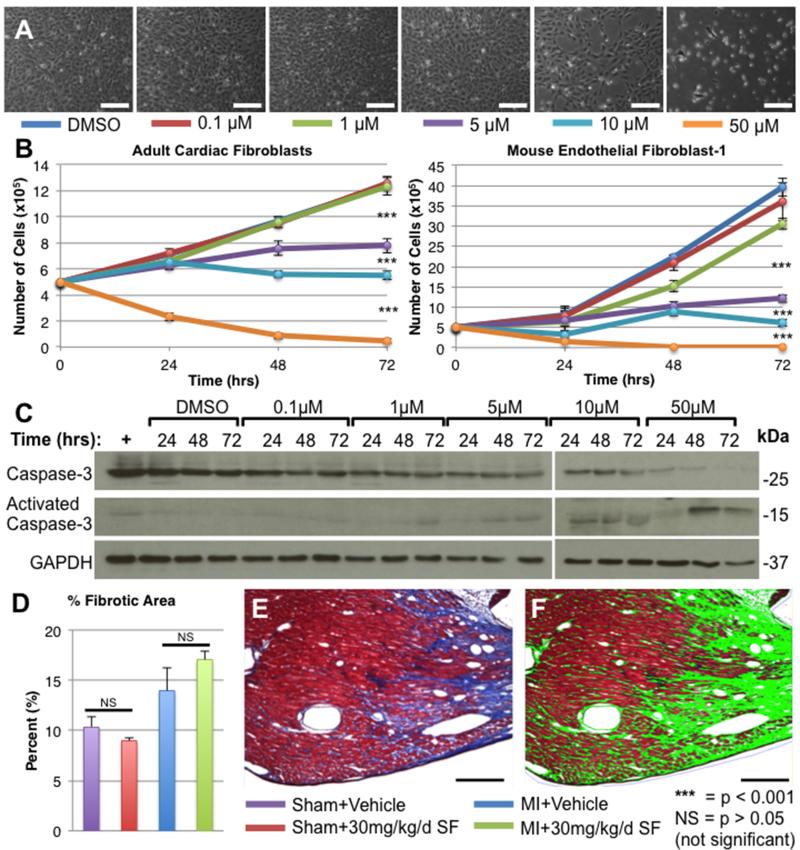

Sorafenib does not affect cardiac fibrosis

The effects of sorafenib on isolated adult cardiac fibroblasts and the mouse endothelial fibroblast-1 (MEF-1) cell line was examined to determine if sorafenib had any effect on post-MI fibrosis. Both fibroblast cell types were plated at low densities (50,000 cells/well) and were allowed to proliferate over 72 hours in the presence of DMSO (control) or 0.1-50 μM sorafenib. In Figure 7A, representative bright field micrographs of MEF-1 cells after 72 hours of exposure to sorafenib are displayed (similar changes were observed in primary mouse adult cardiac fibroblasts cultures; data not included). Cell counts were performed after 24, 48, or 72 hours in culture (Figure 7B). Sorafenib induced a time- and dose-dependent decrease in proliferation of both populations of fibroblasts at doses greater than 5 μM. Lysates were prepared from samples at each time point, and Western analysis against total and activated caspase-3 was performed to determine whether this inhibition of proliferation was due to activation of the apoptotic pathway. Western analysis of MEF-1 lysates demonstrated a time- and dose-dependent activation of caspase-3 in response to sorafenib treatment (Figure 7C). Adult cardiac fibroblasts exhibited similar activation of caspase-3 (data not included).

Figure 7. Sorafenib inhibits isolated fibroblasts in vitro but does not effect post-MI fibrosis in vivo.

Primary adult cardiac fibroblasts or mouse endothelial fibroblast-1 cell line (MEF-1) were treated with DMSO or 0.1-50 μM sorafenib for 72 hours. A) Bright field micrographs of MEF-1 cell cultures after 72 hours of sorafenib treatment. B) Mean cell counts (n=3) at 24, 48 and 72 hours after plating. C) Western analysis of total or activated caspase-3 in MEF-1 cell lysates. Positive control (+) = H2O2-treated MEF-1 cells. D) After 2 weeks post-MI tissues were stained with Masson’s trichrome and the percent of myocardium that was trichrome-positive (blue) was quantified using BioQuant software. A representative bright field micrograph of the infarct border zone 2 weeks post-MI+Sorafenib is displayed (E) along with the BioQuant analysis (F) of the same image (fibrotic tissue = green). ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. All scale bars = 200μm.

The effects of sorafenib on fibrosis in vivo were also examined. The number of mice in this MI model that died prior to sacrifice secondary to rupture of the infarct-related wall was not significantly different between MI animals treated with vehicle or 30 mg/kg/day sorafenib (12.0% v. 9.7%; p=NS). To examine tissue fibrosis, we analyzed Masson’s trichrome-stained tissue sections from hearts fixed 2 weeks post-MI. The percent of total myocardial tissue that was trichrome+ (blue) was determined (Figure 7D). A representative image showing an area of fibrotic scar tissue near the infarct border zone is displayed in Figure 7E along with the corresponding bioquantification analysis (Figure 7F) in which fibrotic tissue is highlighted in green. MI increased the percentage of fibrotic tissue, which is characteristic of the changes seen during post-MI remodeling. However, there was no significant difference in the percentage of fibrotic tissue between Sham+Vehicle vs. Sham+Sorafenib or between MI+Vehicle vs. MI+Sorafenib. Thus, while higher doses (> 5 μM) of sorafenib can inhibit fibroblast proliferation by inducing apoptosis (in vitro), there does not appear to be a significant change in fibrosis associated with sorafenib treatment in vivo.

Sorafenib does not affect infarct size or post-MI neovascularization

The effects of sorafenib on infarct size at 24 hours post-MI and 2 weeks post-MI were examined. Animals from each MI group were selected at random to undergo sacrifice 24 hours post-MI. No significant difference was detected in either area at risk (AAR) or infarct area (IA) between sorafenib and vehicle-treated MI animals (Online Figure IA-B). To measure chronic infarct size, tissue sections from hearts fixed 2 weeks post-MI were stained with Masson’s trichrome (Online Figure IC), and the percentage of total myocardial area that was pathologically fibrotic was determined. After 2 weeks, there was no difference in infarct size between the sorafenib and vehicle-treated MI groups (Online Figure ID).

Sorafenib inhibits receptors for the pro-angiogenic growth factors VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF),2, 7 which are both involved in post-MI neovascularization.14 In order to determine whether sorafenib treatment effected post-MI blood vessel formation, tissues that were fixed at 1 or 2 weeks post-MI were immunostained for α-sarcomeric actin (red) and von Willebrand factor (vWF, green), and nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Representative confocal micrographs of tissues from 2 weeks post-MI+Vehicle or MI+Sorafenib are shown in Online Figure IE. Quantitative confocal histology was used to determine the number of vWF+ vessel structures per visual field (Online Figure IF). No significant difference was found between the number of vWF+ vessels between vehicle or sorafenib-treated MI animals. Thus, sorafenib treatment did not appear to effect post-MI neovascularization within the 2-week time course of these experiments.

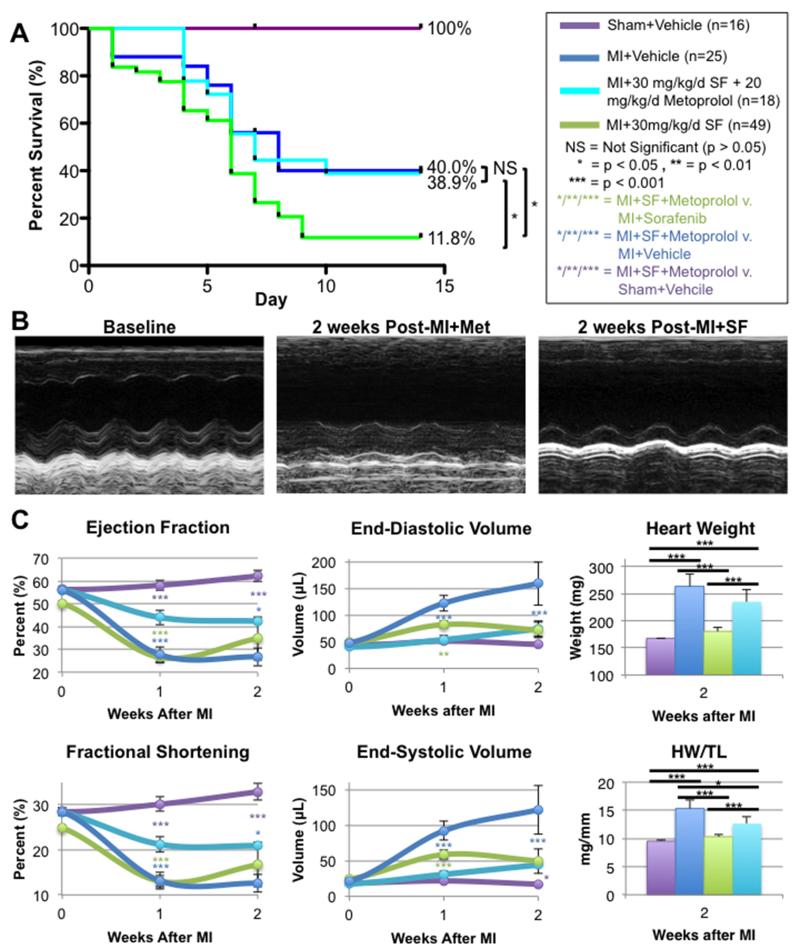

Treatment with metoprolol post-MI prevents sorafenib-induced mortality, improves cardiac function and reduces myocyte cross-sectional area

After MI, activation of the sympathetic nervous system increases the contractility of surviving myocytes and allows the heart to pump sufficient blood to support systemic blood pressure. However, persistent and excessive sympathetic signaling might provoke the damaging effects of sorafenib and contribute to the excess mortality of MI in sorafenib-treated animals. To test this idea, an additional group of mice underwent MI+30mg/kg/d IP sorafenib dosing (n=20), and after MI these mice received 20 mg/kg/d IP metoprolol. Metoprolol treatment improved 2-week survival post-MI to 38.9%, a level not significantly different from vehicle-treated MI controls (Figure 8). These findings suggest that catecholamines contribute to the increased mortality after MI in sorafenib treated animals.

Figure 8. Metoprolol dosing improves post-MI survival and cardiac function of mice treated with sorafenib.

A) Two-week survival of mice treated with vehicle or 30 mg/kg/d sorafenib+20 mg/kg/d metoprolol. Animals treated with 30 mg/kg/d SF alone or vehicle are shown for comparison. B) Representative M-mode echocardiograms of mice 2 weeks after MI with Veh, SF treatment, or SF+Metoprolol treatment. C) Cardiac function and volumes measured by echocardiography and gross heart weight (HW) and HW/tibia length measured after sacrifice.

Additionally, metoprolol treatment improved post-MI ejection fraction and fraction shortening relative to sorafenib-treated controls (Figure 8B-C). Metoprolol also attenuated remodeling relative to vehicle-treated MI controls, as has been widely reported in the literature. At the cellular level, myocytes from metoprolol treated hearts did not have significantly larger cross-sectional areas than vehicle-treated or sham-operated animals and were significantly smaller than myocytes treated with sorafenib alone (Online Figure II), suggesting that metoprolol prevented the pathologic hypertrophy of myocytes observed after sorafenib treatment. Considering that cardiac volumes measured by echocardiography and gross heart weights of Sorafenib+Metoprolol treated animals were significantly larger than mice treated with sorafenib alone (Figure 8C), the smaller myocyte size in the presence of larger overall heart size suggests that metoprolol treatment prevented sorafenib-induced myocyte death.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that sorafenib induces myocyte death, even in the absence of cardiac injury, and when administered in the presence of MI, sorafenib dramatically increases mortality (Figure 1A). This myocyte loss appears to be due to necrosis (possibly a programed form of necrosis53) and not apoptosis (Figure 2G and Figure 6), which is consistent with our previously published reports on imatinib-induced cardiac injury.3 Myocytes that survive the sorafenib treatment undergo pathologic hypertrophy (Figure 3) to maintain contractile mass, and cardiac function remained relatively unchanged (Figure 1C). As surviving myocytes increase in size, they could reach a size at which basic cell metabolism is significantly disrupted, resulting in necrotic cell death. Ultimately, recurrent and widespread myocyte loss leads to hemodynamic instability that can culminate in death. Sorafenib-induced cardiac injury does not appear to be secondary to any direct effects of the drug on cardiac inotropy, as sorafenib lacked any direct negative inotropic effects on isolated myocytes (Figure 2C-F).

In combination with myocyte necrosis, sorafenib also potently induces stem cell apoptosis and inhibits stem cell proliferation in vitro (Figure 4) and in vivo (Figure 5). These effects may inhibit the generation of new cardiac myocytes after MI47, further exacerbating cardiac dysfunction. These findings are consistent with previous research on c-kit-deficient mice, which have markedly reduced post-MI repair and survival.54, 55 The authors of these studies attributed this decreased survival mostly to failed recruitment of stem cells from the bone marrow specifically, but our data shows that c-kit antagonism potently inhibits all pools of cardiogenic stem cells in the body, including those residing in the heart and cortical bone (Figure 4 and 5). Sorafenib potently diminished in vivo BrdU labeling of myocytes and non-myocytes, further suggesting that cardiac repair and new myocyte formation mediated by c-kit+ stem cells is inhibited by sorafenib injury.44

Similar observations have been reported in a mouse model of diabetic cardiomyopathy56, which similarly showed decreased cardiac mass and volume secondary to myocardial cell loss with surviving myocytes undergoing hypertrophy. In this model, CDCs were lost by a 4-fold higher rate of apoptotic death than in myocytes, which were shown to die via necrosis. The authors speculated that hyperglycemia increased local levels of radical free oxygen species (ROS) in the myocardium, and that the differential mechanisms of death between CDCs and myocytes was due to differing susceptibilities of each cell type to ROS. The similarities to our mouse model are striking, suggesting that sorafenib injury might increase the levels of local myocardial ROS, which could explain the differential mechanisms of cell death observed in Figures 2 and 4.

Sorafenib-induced cardiotoxicity does not appear to be related to sorafanib-mediated inhibition of RAF1. Conditional, cardiac-specific RAF1 knockout resulted in cardiac dilation with myocyte apoptosis and increased cardiac fibrosis.57 Our results show that sorafenib induced myocyte necrosis and not apoptosis (Figure 2G and Figure 6) and resulted in decreased heart size rather than dilation (Figure 1C). Necrotic myocyte death and decreased heart size were also observed in our previously published report on imatinib cardiotoxicity,3 suggesting that these anticancer drugs might work through a common pathway. Sorafenib inhibited the growth of both primary adult cardiac fibroblasts and MEF-1 cells in vitro but did not have any effect on the degree of in vivo fibrosis over the time frame of the present experiments (Figure 5). However, the majority of the mortality observed in our MI model occurred before two weeks post-MI, which is still relatively early in the post-MI remodeling process. Thus, it is possible that had our mice survived longer, we may have observed a greater degree of inhibition of fibrosis in vivo. However, our in vitro results suggest that we would not expect any increase in fibrosis as was seen in the conditional RAF1 knockout mouse.57 It does not appear that RAF1 is involved in sorafenib-mediated cardiotoxicity.

Another proposed mechanism of multi-kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity involves antagonism of VEGFR and PDGFR and inhibition of post-MI neovascularization. The heart normally has a robust angiogenic response to ischemic injury to reestablish a supply of oxygen and nutrients to the ischemic tissue.58, 59 Our data would suggest that VEGFR and PDGFR antagonism by sorafenib does not play a major role in the increased mortality observed in this model because after 1 and 2 weeks post-MI, no significant difference in blood vessel density could be detected at the infarct border zone between vehicle- and sorafenib-treated MI mice (Figure 6). However, we have previously shown that the most robust post-MI neovascularization in our animal model occurs after 6 weeks post-MI,14 so it is possible that had the mice survived longer than two weeks we may have observed some decrease in neovascularization in sorafenib treated mice. However, the major mechanism(s) of premature death occurs without any changes in neovascularization and is related to the loss of myocytes and failure of stem cell mediated repair of the heart.

The increased mortality observed after MI in sorafenib-treated animals can be completely reversed by concomitant administration of the β1-adrenergic antagonist metoprolol (Figure 8). The exact mechanism of this improvement in survival and cardiac structure and function was not completely elucidated. However, excessive adrenergic activity in the failing heart is responsible for critical aspects of heart failure progression60 and myocyte death signaling61-63. Our data suggests that metoprolol eliminates sorafenib-mediated myocyte death to improve cardiac function and reduce pathologic hypertrophy and loss of myocytes. Sorafenib appears to require persistent catecholamine signaling to induce excess mortality after MI. We speculate that blocking the increased autonomic outflow to the heart post-MI reduces myocyte loss by blunting Ca2+-overload-induced myocyte necrosis.

Conclusions

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib have revolutionized cancer therapy and saved many lives. Sorafenib continues to be a mainstay in the clinical treatment of RCC and its use is now being expanded to treat other cancers including HCC and melanoma.7 We are not advocating against its future use. However, especially in patients with a known history of cardiac comorbidities, a more thorough cardiac work-up should be considered prior to use of this drug. Furthermore, the presence of these comorbidities demands very close follow-up of patients receiving this agent. There is little availability of baseline cardiac function data in patients who have received this drug in the past, since studies such as echocardiography are rarely warranted in patients with renal carcinoma. However, there is increasing evidence that these sorts of studies should be used to identify patients who might be susceptible to the adverse cardiotoxic features of this drug. Our results would suggest that any ischemic damage or myocardial cell loss is likely to be profoundly exacerbated by sorafenib. Additionally, in any patients that are already at high risk of myocardial infarction (those with ischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, chronic hypertension, etc.) physicians should consider protective adjunct therapies. Finally, our findings suggest that β1-adrenergic antagonists, commonly used heart failure therapeutic agents, could protect patients at risk of sorafenib-mediated cardiotoxicity.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Kinase inhibitors specifically targeting receptors that become constitutively activated in cancer cells while sparing healthy host cells and reducing side effects compared with traditional chemotherapeutics.

The multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib, which is used for the treatment of solid tumors such as renal cell carcinoma, can cause severe cardiac dysfunction in human subjects through unknown mechanisms.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Sorafenib induces loss of myocytes by necrosis without effecting myocyte contractility or overall cardiac function.

Sorafenib treatment induces apoptotic death of stem cells in the heart and bone, which decreases myocyte turnover at the infarct border zone and reduces endogenous repair of the heart post-myocardial infarction (MI), further exacerbating cardiac dysfunction following myocyte loss.

The cardiotoxic effects of sorafenib are reversed by concomitant administration of the selective β1-adrenergic antagonist metoprolol, which reversed the increased mortality caused by sorafenib treatment and prevented sorafenib-induced myocyte loss.

Kinase inhibitors, including sorafenib, are more selective, with a potential of relatively few systemic side effects. Although patients treated with kinase inhibitor live longer, recent clinical evidence has begun to document their cardiotoxicity. In this study, we describe how sorafenib increases mortality after MI in a mouse model. This increased mortality is caused by sorafenib-induced necrotic death of myocytes. The myocyte loss is exacerbated by sorafenib-mediated apoptosis of cardiogenic stem cells, which prevents normal myocyte turnover and inhibits endogenous repair at the infarct border zone. Sorafenib cardiotoxicity was ameliorated by treatment with metoprolol, which improved post-MI survival of sorafenib-treated animals and reduced the degree of myocyte loss. This study suggests that patients with renal cell carcinoma could prophylactically take metoprolol to reduce the risk of cardiotoxicity while remaining on sorafenib to treat their malignancy.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

S.R.H. received NIH grants R01HL089312, T32HL091804, P01HL091799, and R37HL033921. C.A.M. received an AHA predoctoral fellowship.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- KIs

kinase inhibitors

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

VEGF-receptor

- LV

left ventricle

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- MAPK

MAP-kinase

- PDGFR

platelet-derived growth factor-receptor

- CK

creatinine-kinase

- TnT

troponin T

- LVEF

LV ejection fraction

- MI

myocardial infarction

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HW

heart weight

- TL

tibia length

- FS

fractional shortening

- CBSC

cortical bone-derived stem cells

- CDC

cardiac-derived stem cells

- MEF-1

mouse endothelial fibroblast-1

- Vwf

von Willebrand factor

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nature reviews Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Force T, Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibition. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7:332–44. doi: 10.1038/nrc2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerkela R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, Walters B, Shevtsov S, Pesant S, Clubb FJ, Rosenzweig A, Salomon RN, Van Etten RA, Alroy J, Durand JB, Force T. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nature medicine. 2006;12:908–16. doi: 10.1038/nm1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazer B, Humphreys BD, Moslehi J. Effects of novel angiogenesis inhibitors for the treatment of cancer on the cardiovascular system: focus on hypertension. Circulation. 2011;124:1687–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.992230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, Dallabrida SM, Zurakowski D, Nguyen L, Woulfe K, Pravda E, Cassiola F, Desai J, George S, Morgan JA, Harris DM, Ismail NS, Chen JH, Schoen FJ, Van den Abbeele AD, Demetri GD, Force T, Chen MH. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerkela R, Woulfe KC, Durand JB, Vagnozzi R, Kramer D, Chu TF, Beahm C, Chen MH, Force T. Sunitinib-induced cardiotoxicity is mediated by off-target inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase. Clinical and translational science. 2009;2:15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith RA, Schwartz B, Simantov R, Kelley S. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:835–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oka H, Chatani Y, Hoshino R, Ogawa O, Kakehi Y, Terachi T, Okada Y, Kawaichi M, Kohno M, Yoshida O. Constitutive activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer research. 1995;55:4182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patard JJ, Rioux-Leclercq N, Masson D, Zerrouki S, Jouan F, Collet N, Dubourg C, Lobel B, Denis M, Fergelot P. Absence of VHL gene alteration and high VEGF expression are associated with tumour aggressiveness and poor survival of renal-cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1417–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakis JM, Force TL, Rapp UR, Bonventre JV, Avruch J. Mitogen regulation of c-Raf-1 protein kinase activity toward mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:16009–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen LL, Sabripour M, Andtbacka RH, Patel SR, Feig BW, Macapinlac HA, Choi H, Wu EF, Frazier ML, Benjamin RS. Imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2005;7:293–9. doi: 10.1007/s11912-005-0053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Trofimova I, Siggins RW, Lecapitaine N, Cascapera S, Beltrami AP, D’Alessandro DA, Zias E, Quaini F, Urbanek K, Michler RE, Bolli R, Kajstura J, Leri A, Anversa P. Human cardiac stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duran JM, Makarewich CA, Sharp TE, Starosta T, Zhu F, Hoffman NE, Chiba Y, Madesh M, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Houser SR. Bone-derived stem cells repair the heart after myocardial infarction through transdifferentiation and paracrine signaling mechanisms. Circulation research. 2013;113:539–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–5. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rota M, Kajstura J, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Vitale S, Esposito G, Iaffaldano G, Padin-Iruegas ME, Gonzalez A, Rizzi R, Small N, Muraski J, Alvarez R, Chen X, Urbanek K, Bolli R, Houser SR, Leri A, Sussman MA, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells adopt the cardiomyogenic fate in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:17783–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706406104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kajstura J, Rota M, Hall SR, Hosoda T, D’Amario D, Sanada F, Zheng H, Ogorek B, Rondon-Clavo C, Ferreira-Martins J, Matsuda A, Arranto C, Goichberg P, Giordano G, Haley KJ, Bardelli S, Rayatzadeh H, Liu X, Quaini F, Liao R, Leri A, Perrella MA, Loscalzo J, Anversa P. Evidence for human lung stem cells. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1795–806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Rangel EB, Gomes SA, Dulce RA, Premer C, Rodrigues CO, Kanashiro-Takeuchi RM, Oskouei B, Carvalho DA, Ruiz P, Reiser J, Hare JM. C-kit(+) cells isolated from developing kidneys are a novel population of stem cells with regenerative potential. Stem cells. 2013;31:1644–56. doi: 10.1002/stem.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markovic A, MacKenzie KL, Lock RB. FLT-3: a new focus in the understanding of acute leukemia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1168–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birg F, Courcoul M, Rosnet O, Bardin F, Pebusque MJ, Marchetto S, Tabilio A, Mannoni P, Birnbaum D. Expression of the FMS/KIT-like gene FLT3 in human acute leukemias of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages. Blood. 1992;80:2584–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama Y, Asai N, Kawai K, Jijiwa M, Murakumo Y, Ichihara M, Takahashi M. The RET proto-oncogene: a molecular therapeutic target in thyroid cancer. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:143–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA, Rolland F, Demkow T, Hutson TE, Gore M, Freeman S, Schwartz B, Shan M, Simantov R, Bukowski RM. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strumberg D, Awada A, Hirte H, Clark JW, Seeber S, Piccart P, Hofstra E, Voliotis D, Christensen O, Brueckner A, Schwartz B. Pooled safety analysis of BAY 43-9006 (sorafenib) monotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumours: Is rash associated with treatment outcome? Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:548–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, Schleucher N, Korfee S, Tewes M, Faghih M, Brendel E, Voliotis D, Haase CG, Schwartz B, Awada A, Voigtmann R, Scheulen ME, Seeber S. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:965–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark JW, Eder JP, Ryan D, Lathia C, Lenz HJ. Safety and pharmacokinetics of the dual action Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, BAY 43-9006, in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:5472–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awada A, Hendlisz A, Gil T, Bartholomeus S, Mano M, de Valeriola D, Strumberg D, Brendel E, Haase CG, Schwartz B, Piccart M. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetics of BAY 43-9006 administered for 21 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1855–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore M, Hirte HW, Siu L, Oza A, Hotte SJ, Petrenciuc O, Cihon F, Lathia C, Schwartz B. Phase I study to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel Raf kinase and VEGFR inhibitor BAY 43-9006, administered for 28 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1688–94. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, Bojic A, Bojic M, Schukro C, Ruhsam M, Hejna M, Schmidinger H. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5204–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uraizee I, Cheng S, Moslehi J. Reversible cardiomyopathy associated with sunitinib and sorafenib. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1649–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1108849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naib T, Steingart RM, Chen CL. Sorafenib-associated multivessel coronary artery vasospasm. Herz. 2011;36:348–51. doi: 10.1007/s00059-011-3444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arima Y, Oshima S, Noda K, Fukushima H, Taniguchi I, Nakamura S, Shono M, Ogawa H. Sorafenib-induced acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery spasm. J Cardiol. 2009;54:512–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porto I, Leo A, Miele L, Pompili M, Landolfi R, Crea F. A case of variant angina in a patient under chronic treatment with sorafenib. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:476–80. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pantaleo MA, Mandrioli A, Saponara M, Nannini M, Erente G, Lolli C, Biasco G. Development of coronary artery stenosis in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M, Cao Y, Shujath J, Gawlak S, Eveleigh D, Rowley B, Liu L, Adnane L, Lynch M, Auclair D, Taylor I, Gedrich R, Voznesensky A, Riedl B, Post LE, Bollag G, Trail PA. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer research. 2004;64:7099–109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2008;7:3129–40. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang YS, Adnane J, Trail PA, Levy J, Henderson A, Xue D, Bortolon E, Ichetovkin M, Chen C, McNabola A, Wilkie D, Carter CA, Taylor IC, Lynch M, Wilhelm S. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) inhibits tumor growth and vascularization and induces tumor apoptosis and hypoxia in RCC xenograft models. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2007;59:561–74. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, Zhang X, McNabola A, Wilkie D, Wilhelm S, Lynch M, Carter C. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer research. 2006;66:11851–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, Douillard JY, Lathia C, Schwartz B, Taylor I, Moscovici M, Saltz LB. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4293–300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lind JS, Dingemans AM, Groen HJ, Thunnissen FB, Bekers O, Heideman DA, Honeywell RJ, Giovannetti E, Peters GJ, Postmus PE, van Suylen RJ, Smit EF. A multicenter phase II study of erlotinib and sorafenib in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:3078–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao M, Rudek MA, He P, Hafner FT, Radtke M, Wright JJ, Smith BD, Messersmith WA, Hidalgo M, Baker SD. A rapid and sensitive method for determination of sorafenib in human plasma using a liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry assay. Journal of chromatography B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2007;846:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin R, Peng H, Nguyen LP, Dudekula NB, Shardonofsky F, Knoll BJ, Parra S, Bond RA. Changes in beta 2-adrenoceptor and other signaling proteins produced by chronic administration of ‘beta-blockers’ in a murine asthma model. Pulmonary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2008;21:115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorrentino SA, Doerries C, Manes C, Speer T, Dessy C, Lobysheva I, Mohmand W, Akbar R, Bahlmann F, Besler C, Schaefer A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Luscher TF, Balligand JL, Drexler H, Landmesser U. Nebivolol exerts beneficial effects on endothelial function, early endothelial progenitor cells, myocardial neovascularization, and left ventricular dysfunction early after myocardial infarction beyond conventional beta1-blockade. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;57:601–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Litwack G, Alnemri ES. CPP32, a novel human apoptotic protein with homology to Caenorhabditis elegans cell death protein Ced-3 and mammalian interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:30761–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellison GM, Vicinanza C, Smith AJ, Aquila I, Leone A, Waring CD, Henning BJ, Stirparo GG, Papait R, Scarfo M, Agosti V, Viglietto G, Condorelli G, Indolfi C, Ottolenghi S, Torella D, Nadal-Ginard B. Adult c-kit(pos) cardiac stem cells are necessary and sufficient for functional cardiac regeneration and repair. Cell. 2013;154:827–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urbanek K, Rota M, Cascapera S, Bearzi C, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Hosoda T, Chimenti S, Baker M, Limana F, Nurzynska D, Torella D, Rotatori F, Rastaldo R, Musso E, Quaini F, Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells possess growth factor-receptor systems that after activation regenerate the infarcted myocardium, improving ventricular function and long-term survival. Circulation research. 2005;97:663–73. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000183733.53101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angert D, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Zhang H, Chen X, Wang W, Ogorek B, Barbe M, Houser SR. Repair of the injured adult heart involves new myocytes potentially derived from resident cardiac stem cells. Circulation research. 2011;108:1226–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urbanek K, Cesselli D, Rota M, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Boni A, Bolli R, Kajstura J, Anversa P, Leri A. Stem cell niches in the adult mouse heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600635103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, Robbins J, Lee RT. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nature medicine. 2007;13:970–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Gannon J, Lee RT. Bone marrow-derived cell therapy stimulates endogenous cardiomyocyte progenitors and promotes cardiac repair. Cell stem cell. 2011;8:389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palojoki E, Saraste A, Eriksson A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Tikkanen I. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2001;280:H2726–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bialik S, Geenen DL, Sasson IE, Cheng R, Horner JW, Evans SM, Lord EM, Koch CJ, Kitsis RN. Myocyte apoptosis during acute myocardial infarction in the mouse localizes to hypoxic regions but occurs independently of p53. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:1363–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI119656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Henriksen K, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Apoptosis in human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;95:320–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kung G, Konstantinidis K, Kitsis RN. Programmed necrosis, not apoptosis, in the heart. Circulation research. 2011;108:1017–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayach BB, Yoshimitsu M, Dawood F, Sun M, Arab S, Chen M, Higuchi K, Siatskas C, Lee P, Lim H, Zhang J, Cukerman E, Stanford WL, Medin JA, Liu PP. Stem cell factor receptor induces progenitor and natural killer cell-mediated cardiac survival and repair after myocardial infarction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:2304–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fazel S, Cimini M, Chen L, Li S, Angoulvant D, Fedak P, Verma S, Weisel RD, Keating A, Li RK. Cardioprotective c-kit+ cells are from the bone marrow and regulate the myocardial balance of angiogenic cytokines. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:1865–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI27019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rota M, LeCapitaine N, Hosoda T, Boni A, De Angelis A, Padin-Iruegas ME, Esposito G, Vitale S, Urbanek K, Casarsa C, Giorgio M, Luscher TF, Pelicci PG, Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J. Diabetes promotes cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure, which are prevented by deletion of the p66shc gene. Circulation research. 2006;99:42–52. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000231289.63468.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamaguchi O, Watanabe T, Nishida K, Kashiwase K, Higuchi Y, Takeda T, Hikoso S, Hirotani S, Asahi M, Taniike M, Nakai A, Tsujimoto I, Matsumura Y, Miyazaki J, Chien KR, Matsuzawa A, Sadamitsu C, Ichijo H, Baccarini M, Hori M, Otsu K. Cardiac-specific disruption of the c-raf-1 gene induces cardiac dysfunction and apoptosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:937–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI20317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:887–93. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shiojima I, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Schiekofer S, Ito M, Liao R, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Disruption of coordinated cardiac hypertrophy and angiogenesis contributes to the transition to heart failure. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:2108–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI24682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katz AM. Cardiomyopathy of overload. A major determinant of prognosis in congestive heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 1990;322:100–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Communal C, Singh K, Pimentel DR, Colucci WS. Norepinephrine stimulates apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes by activation of the beta-adrenergic pathway. Circulation. 1998;98:1329–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shizukuda Y, Buttrick PM, Geenen DL, Borczuk AC, Kitsis RN, Sonnenblick EH. beta-adrenergic stimulation causes cardiocyte apoptosis: influence of tachycardia and hypertrophy. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275:H961–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubo H, Margulies KB, Piacentino V, 3rd, Gaughan JP, Houser SR. Patients with end-stage congestive heart failure treated with beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists have improved ventricular myocyte calcium regulatory protein abundance. Circulation. 2001;104:1012–8. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.