There is evidence of a long-term benefit of adjuvant post operative chemotherapy for early-stage ovarian cancer. The magnitude of benefit is greatest in patients at a higher risk of recurrence defined as stage 1B/1C grade 2/3, any stage 1 grade 3 or clear cell histology. The use of single agent carboplatin is recommended.

Keywords: early-stage ovarian cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy, ICON1, ICON3

Abstract

Background

There is no clear consensus regarding systemic treatment of early-stage ovarian cancer (OC). Clinical trials are challenging because of the relatively low incidence and good prognosis. Initial results of the International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm (ICON)1 trial demonstrated benefit in both overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) with adjuvant chemotherapy. We report results of 10-year follow-up to establish whether benefits are maintained longer term and discuss how this and other available evidence from randomised trials can be used to guide treatment options regarding the need for, and choice of, adjuvant chemotherapy regimen.

Patients and methods

ICON1 recruited women with OC following primary surgery in whom there was uncertainty as to whether adjuvant chemotherapy was indicated. Patients were randomly assigned to adjuvant or no adjuvant chemotherapy. Platinum-based chemotherapy was recommended and 87% received single-agent carboplatin. Analyses of long-term treatment benefits and interaction with risk groups were carried out. A high-risk group of women was defined with stage 1B/1C grade 2/3, any stage 1 grade 3 or clear-cell histology.

Results

With a median follow-up of 10 years, the estimated hazard ratio (HR) for RFS was 0.69 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51–0.94, P = 0.02] and OS 0.71 (95% CI 0.52–0.98, P = 0.04) in favour of chemotherapy. In absolute terms, there was a 10% (60%–70%) improvement in RFS and a 9% (64%–73%) improvement in OS; the benefit of chemotherapy might be greater in high-risk disease (18% improvement in OS). Uncertainty remains about the optimal chemotherapy regimen. The only randomised trial data available are from a subset of 120 stage 1 patients in ICON3 where the treatment difference, comparing carboplatin with carboplatin/paclitaxel was estimated with relatively wide CIs [progression-free survival HR = 0.71 (95% CI 0.39–1.32) and OS HR = 0.98 (95% CI 0.49–1.93)].

Conclusions

Extended follow-up from ICON1 confirms that adjuvant chemotherapy should be offered to women with early-stage OC, particularly those with high-risk disease.

Clinical trial numbers

ISRCTN11916376 for ICON1 and ISRCTN57157825 for ICON3.

introduction

Early-stage ovarian cancer (OC) comprises about 20% of all cases of OC [1]. The prognosis of early-stage disease is significantly better than late-stage disease, with 5-year survival varying from 80%–93% (stage 1/2) to <30% (stage 3/4) [2–5]. There is no clear consensus regarding systemic treatment of early-stage OC in terms of the need for, and choice of, adjuvant chemotherapy regimen; these questions are however critical for women with early-stage OC, aiming to maximise cure while minimising treatment toxicities. Clinical trials in this setting are challenging because of the relatively low disease incidence and good prognosis (requiring long follow-up).

In the 1990s, two trials [International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm (ICON)1 and ACTION] were conducted to address the uncertain survival benefit of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage disease [6, 7]. The primary analysis of ICON1, with a median follow-up of 4 years demonstrated a significant improvement in both recurrence-free survival (RFS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.46–0.91, P = 0.01] and overall survival (OS) (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.45–0.97, P = 0.03) in favour of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy [7]. Very similar findings were reported in the ACTION trial [6]. We present here the 10-year follow-up results of ICON1 to investigate whether the initial reported benefits were maintained in longer term and to explore whether the effect of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy was different based on a stratification for risk of disease recurrence [8] (classified according to tumour stage and tumour grade) with a larger number of RFS and OS events observed from the longer follow-up.

When immediate adjuvant chemotherapy is used in early-stage OC, the choice of optimal chemotherapeutic regimen remains unclear. We provide an extensive discussion with a systematic review of randomised, controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy including women with early-stage OC to explore evidence for the effect of combination chemotherapy, or treatment intensification, in early-stage OC.

methods

patients

ICON1 was an international randomised phase III trial, started in 1991. Patients with histologically confirmed epithelial OC were eligible if, in the opinion of the treating physician, there was uncertainty as to whether the patient required immediate adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients had to be fit to receive chemotherapy, with no previous malignant disease (excepting non-melanomatous skin cancer) and to have not received any previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The surgical requirements were that all visible tumour had to be removed, but recommending minimally total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy, consistent with standard practice at that time. Ethical approval of the local institution and written informed consent for all patients were required.

treatment

Patients were randomly assigned with a 1:1 ratio to receive immediate adjuvant chemotherapy or no immediate adjuvant chemotherapy. Six cycles of chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin (87% of patients received) or the three-drug combination cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin (CAP) was recommended, although alternative platinum-based regimens were also allowed. No patients received paclitaxel. The planned chemotherapy regimen for a patient was specified before individual randomisation. Further details of the doses recommended are provided in the original publication [7].

long-term follow-up

ICON1 pre-specified follow-up to continue for RFS and OS to investigate whether the long-term benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was maintained and to explore any differential effect based on recurrence risk [8]. Women were classified as low risk (stage 1A grade 1), intermediate risk (stage 1A grade 2 or stage 1B/1C grade 1) and high risk (stage 1B/1C grade 2/3 and any stage 1 grade 3 or clear cell histology) (Table 1). This was pre-specified before the dataset lock for analyses and based on a review of published data, clinical consensus and taking into account the distribution of patients (without reference to outcomes) to have the most power from a comparison of roughly equal groups (low/intermediate risk versus high risk). Survival follow-up information was cross-checked with the UK Office of National Statistics and Italian Vital Statistics Offices.

Table 1.

Classification of stage 1 patients by risk of recurrence

| Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1A | 13 | 20 | 10 |

| Stage 1B | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Stage 1C | 15 | 17 | 12 |

Figures represent the proportion of patients in ICON1 (2% unknown). Light grey represents low risk (13%); medium grey represents intermediate risk (38%); dark grey represents high risk (47%).

statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was OS, defined as time from randomisation to death from any cause. The secondary outcome measure was RFS, defined as the time from randomisation to clinically defined recurrence or death from any cause. Kaplan–Meier curves of RFS and OS were compared using the standard log-rank test. Flexible parametric models [9] were applied for estimating difference of RFS and OS between two arms overtime. A χ2 test for interaction between treatment allocation and risk groups was carried out for both RFS and OS outcome measures. All analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis and all statistical tests were two sided.

results

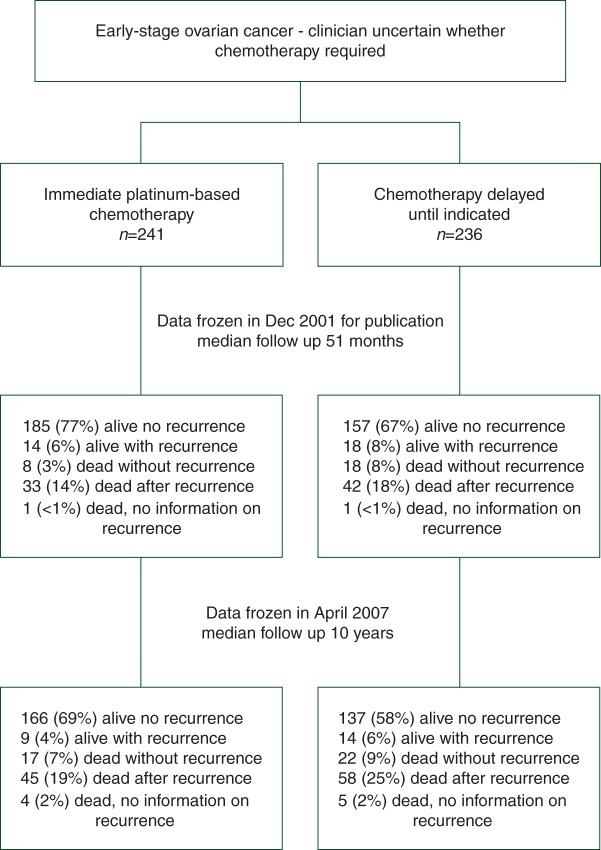

Between August 1991 and January 2000, 477 women (241 immediate adjuvant chemotherapy, 236 no immediate adjuvant chemotherapy) with epithelial OC were recruited from 84 centres in five countries. Patient characteristics were well balanced between the two arms for accrual country, age, tumour stage, residual bulk of disease, degree of tumour differentiation and histological subtype. Figure 1 shows the ICON1 CONSORT diagram. Full details of the chemotherapy administered are provided in the original publication [7].

Figure 1.

International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial (ICON1) profile. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) into either immediate adjuvant chemotherapy arm or no immediate adjuvant chemotherapy arm.

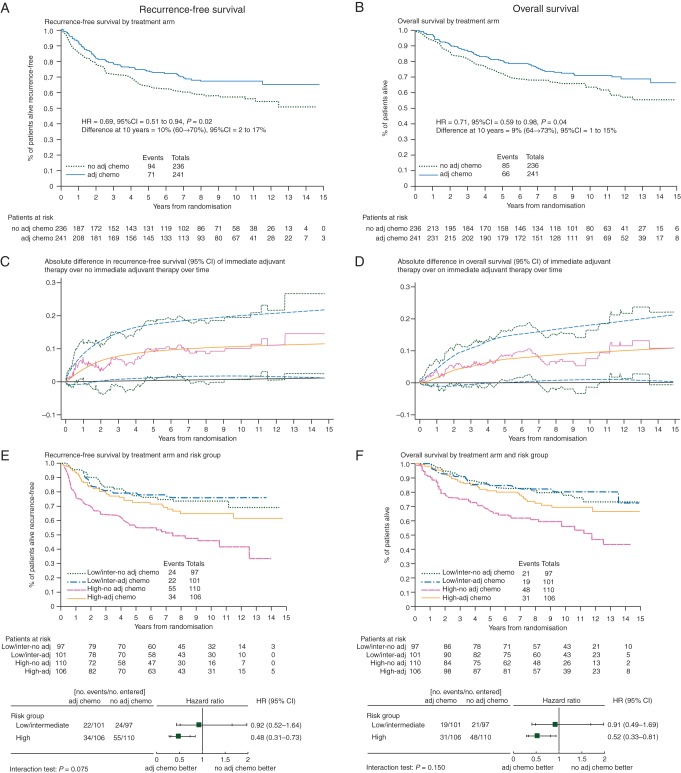

The median follow-up is now 10 years with a total of 165 (35%) women who have developed disease recurrence or died (71 adjuvant chemotherapy, 94 no adjuvant chemotherapy). Comparison of Kaplan–Meier curves for RFS gives an estimated HR = 0.69 (95% CI 0.51–0.94, P = 0.02) (Figure 2A). This translates into a 10% RFS improvement from immediate adjuvant chemotherapy at 10 years, from 60% to 70%. The absolute difference of RFS and 95% CI of the difference between immediate adjuvant therapy over no immediate adjuvant therapy over time is displayed in Figure 2C.

Figure 2.

Updated ICON1 results with median follow-up 10 years.

A further 48 women have died, giving 151 (32%) deaths in total (66 adjuvant chemotherapy, 85 no adjuvant chemotherapy). Seventy-two percent of all deaths were attributed to OC. Comparison of Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 2B) gave an estimated HR = 0.71 (95% CI 0.52–0.98, P = 0.04) in favour of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy, translating into a 9% OS improvement at 10 years, from 64% to 73%. The absolute difference of OS from immediate adjuvant therapy over no immediate adjuvant therapy over time is displayed in Figure 2D.

The effect of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy in stage 1 patients (n = 428) by recurrence risk was explored (Table 1, Figure 2E for RFS and Figure 2F for OS). The benefit of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy appears greatest in women with high-risk stage 1 disease. In these women, for RFS the HR = 0.48 (95% CI 0.31–0.73, P < 0.001) equates to an improvement at 10 years of 23% (95% CI 11% to 33%) from 45% to 68%. For OS in these women, the HR = 0.52 (95% CI 0.33–0.81, P = 0.004) translates into an 18% (95% CI 7% to 27%) improvement at 10 years, from 56% to 74%. In the low/intermediate-risk groups, for RFS, the HR = 0.92 (95% CI 0.52–1.64, P = 0.78) equates with a 2% (95% CI −13% to 12%) improvement at 10 years from 73% to 75%; for OS the HR = 0.91 (95% CI 0.49–1.69, P = 0.77) gives an improvement at 10 years of 2% (95% CI −12% to 11%) from 78% to 80%. The tests for interaction for RFS (P = 0.075) and OS (P = 0.15) suggest a different size of effect between the high-risk versus low/intermediate-risk groups, but the trial was not powered for testing such an interaction.

choice of chemotherapeutic regimen in early-stage OC

A systematic literature search was carried out to identify phase III trials of systemic first-line adjuvant therapy (see supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online). Apart from the ICON1 and ACTION trials, only four reported analyses relating to early-stage disease [10–13]. No evidence of a benefit was shown in early-stage OC with respect to treatment intensification by increasing dose density [12] or by adding a third drug [11] or maintenance paclitaxel [13]. It is acknowledged that patient numbers were small within the trials not specific to early-stage OC. Only one study specifically informs the duration of standard therapy in early-stage OC (GOG157) [10]; this trial compared three versus six cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel. No evidence of a difference in RFS or OS was shown, although increased toxicity occurred with six cycles.

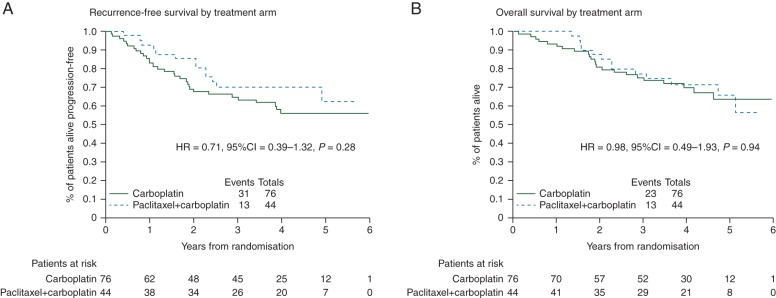

In clinical practice, both carboplatin and carboplatin/paclitaxel are used in early-stage OC. No prospective randomised clinical trials have directly compared carboplatin and carboplatin/paclitaxel in this setting; however, data were available from 120 stage 1 patients enrolled into the ICON3 trial [14] (supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online). These data show a trend towards improved progression-free survival (PFS) in favour of carboplatin/paclitaxel (HR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.39–1.32, P = 0.28) (Figure 3A) but no evidence of a difference in OS between the arms (HR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.49–1.93, P = 0.94) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Stage 1 patients randomised to carboplatin versus paclitaxel + carboplatin in ICON3 trial.

discussion

These updated data from ICON1 confirm the long-term RFS and OS benefit from adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in women with early-stage OC. Results are consistent with previous trials and a meta-analysis [7, 15–17]. The magnitude of benefit appears greatest in women with high-risk disease, which indicates that chemotherapy should be standard of care in these patients. A small benefit in women with lower risk disease cannot be excluded, and chemotherapy should be discussed, considering individual patient and disease characteristics including cyst rupture, age and histological subtype [18–20].

The choice of the optimal adjuvant chemotherapy regimen and the duration of treatment in early-stage OC is a subject of continuing debate. There were no treatment-related deaths in ICON1, but cytotoxic chemotherapy can have potentially serious and/or long-term complications [21], which are increased when taxanes are added to platinum-based therapy. In clinical practice, both carboplatin and carboplatin/paclitaxel are used in this setting, although there is no clear evidence base to support the use of combination therapy. Single-agent carboplatin was the chemotherapy most frequently used in ICON1 and ACTION and thus was the treatment recommended in first reports of these trials. The retrospective analyses comparing carboplatin with carboplatin/paclitaxel using the 120 stage 1 patients in the ICON3 trial lead to wide CIs in the estimates of treatment difference. Some will argue that the HR of 0.71 for PFS, despite the wide CIs, supports the use of carboplatin/paclitaxel, whereas others will argue that the HR of 0.98 for OS and increased toxicities with doublet therapies supports the use of single-agent carboplatin. However, in the absence of any prospective comparative randomised trials in this setting, with observed estimated HR of 0.98 in OS, we support the use of less toxic single-agent carboplatin. Further evidence for carboplatin alone comes from a small retrospective study which demonstrated no evidence of a difference in OS between carboplatin and carboplatin/paclitaxel [22]. There was also no evidence from the trials identified in the systematic review supporting treatment intensification (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of published studies of adjuvant chemotherapy in ovarian cancer allowing inclusion of patients with early-stage disease (I and/or IIA) and with available (ICON3) or reported (others) early-stage analyses

| Study | Number | Eligibility | % |

Control arm | Research arm | No. of cycles | Recruit | HR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III/IV | ||||||||

| ICON1 [7] 2003 |

477 | Uncertain of benefit from chemotherapy | 93 | 6 | 1 | Observation | Platinum based (most carboplatin/CAP) | 6 | 08/91-04/00 | Overall OS HR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.52–0.98, P = 0.04 |

| ACTION 2010 [18] |

448 | Ia–Ib, grade II–III; all stages Ic and IIa, and all stages I–IIa with clear-cell | 93 | 7 | 0 | Observation | Platinum based | 6 | 11/90-01/00 | Overall CSS HR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.48–1.13, P = 0.16 |

| ICON3 [14] | 2074 | FIGO stage I–IV | 9 | 11 | 80 | Carboplatin AUC5 ‘or’ Cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 Doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 Cisplatin 50 mg/m2 |

Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC5 |

6 | 02/95-10/98 | Stage I OS HR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.49–1.93, P = 0.94 |

| GOG157 [10] | 427 | FIGO stage Ia/b grade 3, clear cell, Ic and completely resected stage II | 69 | 31 | 0 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC 7.5 [3 cycles] |

Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC7.5 [six cycles] |

3 versus 6 | 03/95–05/98 | Overall RFS HR = 0.761, 95% CI 0.51–1.13, P = 0.18 |

| AGO-OVAR/GINECO/NSGO [11] | 1742 | All | 8 | 10 | 82 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC5 |

Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC5 Gemcitabine 800 mg/m2 day 1/day 8 |

6 | 2002–2004 | Stage I/IIA OS HR = 3.28, 95% CI 0.89–12.11, P = 0.06 (in favour of standard arm, but events scarce) |

| JGOG [12] | 631 | FIGO ≥stage II | 0 | 18 | 82 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC6 |

Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 day 1, 8, 15) Carboplatin AUC6 |

6 | 04/03-12/05 | Stage II PFS (n = 116) HR = 0·81, 95% CI 0·36–1·82 |

| GOG-175 [13] | 542 | FIGO stage 1A/B grade 3/clear cell or 1C/II | 72 | 28 | 0 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC6 |

Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) Carboplatin AUC6 followed by Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2, 1 h) q1w |

6 24 weeks |

09/98-12/06 | All RFS HR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.57–1.15 |

ICON1 was a pragmatic trial aligned with routine clinical practice at the time, designed to include patients in whom the indication for adjuvant chemotherapy was uncertain, and without mandating specific disease staging. Because of this, there has been comment that there was an unknown proportion of patients with non-optimally surgically staged disease, who could have had undetected more advanced disease [23]. While this is true, even 15 years after ICON1 was started, delivering optimal staging surgery in women with early-stage OC remains a challenge. An incidental diagnosis of OC is still made in some women following laparotomy or laparoscopy carried out for expected benign disease and staging is often incomplete [24]. ICON1 remains the largest trial ever carried out in early-stage OC and remains relevant. It is unlikely that trials in this setting of this size will be repeated. The long-term follow-up of ICON 1 provides important confirmatory results that aid decision making by clinicians treating women with early-stage OC.

The updated results of ACTION trial [17] concentrate on a retrospective subgroup analysis investigating the effect of immediate adjuvant chemotherapy in patients optimally surgically staged and those non-optimally surgically staged. They claim to demonstrate a benefit only in non-optimally surgically staged patients, while the number of RFS and cancer-specific survival events (36 and 19, respectively) in the subgroup of optimally surgically staged patients (n = 151) are very small. Using risk group classified similar to the published risk stratification [8], however, it appeared in ICON1 that there was a greater benefit from chemotherapy in women with high-risk stage 1 disease. In this subgroup at 10 years, the absolute RFS benefit was 23% and the absolute OS benefit was 18%. In the low/intermediate-risk groups, the benefits seen were much smaller (2% for RFS and 2% for OS at 10 years). This type of exploratory analysis was not possible in the ACTION trial as patients with lower risk disease (grade 1 stage 1A/1B) were excluded. In our opinion, given the initial and long-term follow-up results of ICON1, the ACTION subgroup analyses do not provide sufficient evidence to exclude any benefit in optimally staged patients and should not lead to immediate adjuvant chemotherapy being withheld from optimally staged patients with early-stage OC.

In conclusion, the benefit of adjuvant postoperative chemotherapy for early-stage OC is confirmed with long-term follow-up of ICON1, and it appears that the magnitude of benefit is greatest in patients with features that place them at a higher risk of recurrence. The use of single-agent carboplatin is recommended.

funding

ICON1 was supported in Italy by Fondazione Nerina e Mario Mattioli, in the UK by the UK Medical Research Council, and in Switzerland by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research. ICON3 was supported by the UK Medical Research Council; reduced price paclitaxel and funding for some data management was provided by Bristol Myers Squib [no grant numbers].

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank all ICON1 and ICON3 patients who volunteered to take part in the trial. We also thank staff at all participating sites for ICON1 and ICON3.

references

- 1. SEER_faststats: Stage Distribution (SEER Summary Stage 2000) for ovarian cancer, all ages, all races, female: 2000–2008.

- 2.Oncology FCoG. Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.015. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RC, Walton LA, Ellenberg SS, et al. Adjuvant therapy in stage I and stage II epithelial ovarian cancer. Results of two prospective randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1021–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004123221501. doi:10.1056/NEJM199004123221501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holschneider CH, Berek JS. Ovarian cancer: epidemiology, biology, and prognostic factors. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1098-2388(200007/08)19:1<3::aid-ssu2>3.0.co;2-s. doi:10.1002/1098-2388(200007/08)19:1<3::AID-SSU2>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S161–S192. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60033-7. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:113–125. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.2.113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo N, Guthrie D, Chiari S, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1: a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early-stage ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:125–132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.2.125. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergote I, Amant F. Time to include high-risk early ovarian cancer in randomized phase III trials of advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royston P, Parmar MK. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med. 2002;21:2175–2197. doi: 10.1002/sim.1203. doi:10.1002/sim.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, et al. Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.013. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.du Bois A, Herrstedt J, Hardy-Bessard AC, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without gemcitabine in first-line treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4162–4169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4696. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, et al. Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61157-0. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannel RS, Brady MF, Kohn EC, et al. A randomized phase III trial of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel × 3 courses followed by observation versus weekly maintenance low-dose paclitaxel in patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.013. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ICON3 writing committee. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09738-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trimbos JB, Parmar M, Vergote I, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1 and Adjuvant ChemoTherapy In Ovarian Neoplasm trial: two parallel randomized phase III trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:105–112. doi:10.1093/jnci/95.2.105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winter-Roach BA, Kitchener HC, Dickinson HO. Adjuvant (post-surgery) chemotherapy for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004706. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004706.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trimbos B, Timmers P, Pecorelli S, et al. Surgical staging and treatment of early ovarian cancer: long-term analysis from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:982–987. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq149. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet. 2001;357:176–182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03590-X. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan J, Fuh K, Shin J, et al. The treatment and outcomes of early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: have we made any progress? Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1191–1196. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604299. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan JK, Tian C, Monk BJ, et al. Prognostic factors for high-risk early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2008;112:2202–2210. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23390. doi:10.1002/cncr.23390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Travis LB, Holowaty EJ, Bergfeldt K, et al. Risk of leukemia after platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:351–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902043400504. doi:10.1056/NEJM199902043400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams G, Zekri J, Wong H, et al. Platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: single or combination chemotherapy? BJOG. 2010;117:1459–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02635.x. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young RC, Decker DG, Wharton JT, et al. Staging laparotomy in early ovarian cancer. JAMA. 1983;250:3072–3076. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03340220040030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmers PJ, Zwinderman AH, Coens C, et al. Understanding the problem of inadequately staging early ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:880–884. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.012. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.