Abstract

Although several signal peptide-trapping methods have been devised and used to detect signal sequences, none have relied on using E.coli to identify eukaryotic proteins with signal peptides. Here, we describe a system for selecting human secreted and membrane proteins in E. coli followed by the direct validation of secretion in human cells. The method is based on cDNA fusions to a leaderless β-lactamase reporter gene to isolate clones encoding signal peptides of human genes. We found that β-lactamase fusion proteins carrying a eukaryotic signal peptide at its N-terminus were able to direct their export into the periplasm in E. coli to confer survival upon challenge with carbenicillin. When libraries constructed from 5′ end-enriched cDNAs fused to β-lactamase were screened in E.coli, approximately 0.5%–1% of the cDNAs are selected, and over half of the surviving clones were found to encode for secreted fusion proteins when tested in human cells. These clones were sequenced and shown to represent human genes encoding signal peptides of secreted and membrane proteins. We conclude that this is an efficient and effective strategy to easily enrich cDNA libraries for the identification of novel genes likely to encode secreted enzymes, growth factors, and receptors.

The targeting of both secreted and transmembrane proteins to the secretory pathway is accomplished via the presence of a short, amino terminal sequence known as the signal peptide, signal sequence, or secretory leader sequence (von Heijne 1985; Kaiser and Botstein 1986). The signal peptide itself contains several elements necessary for optimal function, the most important of which is a hydrophobic component. Immediately preceding the hydrophobic sequence is often one or more basic amino acids. The carboxyl terminal end of the signal peptide has a pair of small and uncharged amino acids separated by a single intervening amino acid which defines the signal peptidase cleavage site. Although the hydrophobic component, basic amino acid, and peptidase cleavage site can usually be identified in the signal peptide of known secreted proteins, the short lengths of these motifs and the high level of degeneracy within any one of these elements makes it difficult to identify or isolate secreted or transmembrane proteins solely by searching for signal peptides in DNA databases, or based upon hybridization with DNA probes designed to recognize cDNAs encoding signal peptides. A number of different methods have thus been developed to aid in the identification of such proteins. For example, cDNAs encoding novel secreted and membrane bound mammalian proteins are identified by detecting their secretory leader sequences using the yeast invertase gene as a reporter system (Klein et al. 1996; Jacobs et al. 1997). In another example, genes having signal sequences are identified through cell proliferation and/or differentiation (Kojima and Kitamura 1999). Another method describes the use of alkaline phosphatase as a reporter gene for selecting nucleic acids encoding signal peptide sequences (Hoffman and Wright 1985; Chen and Leder 1999). Yet other methods for signal sequence trapping have relied on using fusions to the interleukin-2 receptor (Tashiro et al. 1993), or to CD4 (Imai et al. 1996). All these methods require time-consuming steps, and most of them rely on the labor-intensive use of mammalian cells as the primary selection mechanism. In the present work, we tested the use of Escherichia coli to identify human genes encoding signal peptides. We demonstrate that E. coli is capable of using mammalian signal sequences to correctly process and direct the translocation of the β-lactamase fusion protein across its cytoplasmic membrane into the periplasm. We further show that selection in E.coli leads to an eightfold enrichment for clones capable of secretion in a human cell line. Additionally, these clones were sequence characterized, and most were found to truly represent genes encoding secreted and membrane proteins. Given the great efforts presently being expended to discover novel secreted and transmembrane proteins as potential therapeutic agents, we believe this method provides an improved system which can simply and efficiently identify the coding sequences of such proteins in mammalian recombinant DNA libraries.

RESULTS

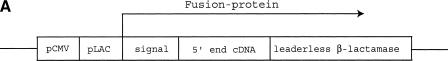

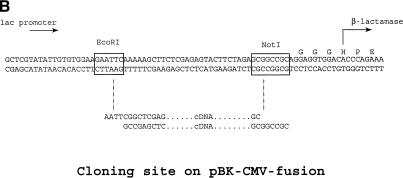

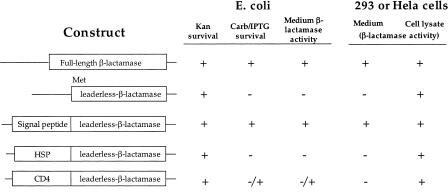

The pBK-CMV vector (Stratagene) contains a CMV promoter to drive the mammalian expression of the fusion gene product, as well as a Lac promoter, which drives the prokaryotic expression. 5′ end-enriched cDNA was cloned unidirectionally upstream of a leaderless β-lactamase gene to effect the expression of a fusion protein with the N-terminus encoded by the inserted cDNA (Fig. 1). In order for the E. coli to survive the antibiotic challenge, the signal sequence and translation initiator ATG codon must be supplied by the cDNA, which must also be cloned in-frame with the leaderless β-lactamase reporter. Detection of β-lactamase activity was accomplished using nitrocefin as a chromogenic substrate (Smith et al. 1987). In the presence of active enzyme, a shift in absorbance from 390 nm to 486 nm is detected upon cleavage of the β-lactam ring. Five constructs were generated and tested to determine the ability of each to survive carbenicillin challenge in E. coli, and for export into the extracellular space in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (Fig. 2). The full-length β-lactamase and leaderless-β-lactamase constructs were used for secreted and intracellular control, respectively. A short signal peptide, the N-terminus of HSPCA, or full-length CD4 was cloned in-frame upstream of the leaderless β-lactamase gene. The kanamycin resistance gene on pBK-CMV confers survival in all constructs when challenged with this antibiotic. However, only when expression of the β-lactamase fusion protein was preceded by a signal peptide from CD4 or β-lactamase did the clone survive carbenicillin challenge. Surprisingly, in the case of the CD4 fusion, only less than 0.1% of the clones tested survived and gave detectable amounts of β-lactamase in the E. coli growth media. The low survival rate of the CD4-fusion clone is most likely due to toxicity in E. coli associated with the CD4 transmembrane domain. Next, these five constructs were tested in HEK 293 cells, and the prokaryotic β-lactamase signal peptides were shown to be as effective in directing extracellular protein export in this mammalian cell line. The CD4–β-lactamase fusion was not detected in the cell media as CD4, a type I membrane protein, would position β-lactamase, joined to its C-terminus, within the cytoplasmic space. However, when the HEK 293 cells were lysed, all five constructs had detectable intracellular β-lactamase, demonstrating adequate expression of the protein.

Figure 1.

(A) The arrangement of E. coli and mammalian promoters in relation to the cDNA and leaderless β-lactamase gene. (B) The sequences at the multiple cloning site of pBK-CMV-fusion where the cDNA fuses with the leaderless β-lactamase gene.

Figure 2.

For each of the constructs listed, the E. coli growth media or the HEK 293 cell culture media was removed and tested for β-lactamase activity. Cell lysates from the HEK 293 cells were obtained to assay for the expression of an active β-lactamase fusion protein. The ability of the clone to survive the carbenicillin challenge is indicated by (+). Detection of β-lactamase in the media or cell lysate is also indicated by (+). In the CD4 fusion construct, a (-/+) sign indicates that only a small percentage (0.1%) of tested clones survived the carbenicillin challenge.

To determine whether or not the carbenicillin challenge specifically selected for clones encoding extracellular proteins, 192 randomly selected clones were picked from plates either with or without carbenicillin. When assayed in E. coli for secretion, 85.9% of the surviving clones produced β-lactamase fusion proteins that were detected in the media, compared to only 5.3% when clones were picked in the absence of carbenicillin (Table 1). When tested in the HEK 293 cells, 54.2% of the cells expressed secreted fusion proteins when transfected with clones that had first been selected with carbenicillin in E. coli, an eightfold increase above the 6.8% observed with unselected cells. This clearly demonstrated that some proteins deemed for extracellular export in human cells were also able to direct the export of β-lactamase in E. coli as well. We next investigated whether extracellular fusion proteins in the HEK 293 cells were truly derived from cDNAs of genes known or thought to be secreted or present on the cell surface. We screened 100,000 clones prepared from a mixture of several different tissue sources (cerebellum, pituitary, lung, kidney, heart, adrenal gland, lymph node, placenta, and ovary) on carbenicillin plates. This led to the selection of 436 surviving clones (0.44%). The plasmid DNA from these clones was recovered and transfected into HEK 293 cells. Of the 436 clones, 282 (64.7%) were scored as `positive' in the nitrocefin assay. The remaining 167 clones had absorbance readings of less than 0.1 and were scored as `negative'. Repeat transfections performed with the same clones showed that the results were consistent and reproducible (data not shown). The cDNA inserts of the 282 positive clones were completely sequenced. The protein identity of half of these clones could not be determined either because they were novel (less than 95% identity over 50 amino acids), or they represented noncoding UTR regions. The other half represented 65 distinct proteins that have been previously identified or characterized (Table 2). The average protein size of these 65 genes was 623 amino acids-long, and the average size of the clone insert cDNAs representing them was 505 bp (data not shown). Forty-six of the 65 genes were cloned at their 5′ mRNA end (i.e., within the first 30 amino acids), demonstrating the efficiency of capturing the start codon and signal peptide using our 5′ bias cDNA library construction method (data not shown). Of the 65 proteins, 38 (58.5%) are thought to be secreted or located at the cell surface; 24 (36.9%) are intracellular, and the location of the remaining three proteins could not be reliably determined. Ten of the 24 intracellular proteins were endoplasmic reticulum, golgi, lysosomal, or mitochondrial proteins, that is, proteins processed through the secretory pathway but not exported from the cell.

Table 1.

Comparison of Unselected and Selected Clones

|

Unselected clones (192)

|

Selected clones (192)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not secreted | Secreted | Not secreted | Secreted | |

| E. coli | 182 (94.8%) | 10 (5.2%) | 27 (14.1%) | 165 (85.9%) |

| 293 cell line | 179 (93.2%) | 13 (6.8%) | 88 (45.8%) | 104 (54.2%) |

Table 2.

Positive Clones from the 293 Cell Line Assay Representing Previously Identified Proteins

| No. | NCBI accession | Protein | Absorbance 486 nm | Localization | Putative signal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell surface or secreted proteins | ||||||||||

| 1 | 806752 | Na,K-ATPase alpha-1 subunit | 0.12 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MLLWIGAILCFLAYSIQA | |||||

| 2 | 7861733 | low density liproprotein receptor related | 0.12 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 3 | 4151807 | membrane-associated guanylate kinase-interacting protein 2 | 0.13 | cell surface, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 4 | 66344454 | betaglycan, TGF-receptor type III | 0.13 | cell surface or secreted, prediction | MTSHYVIAIFALMSFCLA | |||||

| 5 | 699577 | lumican (keratan sulfate proteoglycan | 0.13 | secreted, experimental | MSLSAFTLFLALIGGTSG | |||||

| 6 | 2529742 | Rb-8 neural cell adhesion molecule | 0.13 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MSLLLSFYLLGLLVRSGQA | |||||

| 7 | 180948 | carboxylesterase | 0.13 | secreted, experimental | MWLRAFILATLSASAAWA | |||||

| 8 | 5923891 | cyclophilin-related protein | 0.13 | cell surface, 1 TM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 9 | 9664928 | frizzled-3 | 0.13 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MAMTWIVFSLWPLTVFMGHIGG | |||||

| 10 | 34618 | MGP precursor (AA-19 to 84) | 0.14 | secreted, experimental | MKSLILLAILAALAVVTLC | |||||

| 11 | 6560599 | small solute channel 1 | 0.14 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 12 | 758063 | gastric lipase precursor | 0.14 | secreted, experimental | MWLLLTMASLISVLGTTHG | |||||

| 13 | 179720 | complement protein C8 beta subunit | 0.15 | secreted, prediction | MKNSRTWAWRAPVELFLLCAALGCLS | |||||

| 14 | 3329376 | E25 protein | 0.15 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MLTLLGLSFILAGLIVGGAC | |||||

| 15 | 6165625 | procollagen C-terminal proteinase | 0.16 | secreted, prediction | MRGANAWAPLCLLLAAATQLSRQQS | |||||

| 16 | 506404 | cadherin-11 | 0.16 | cell surface, 1TM, experimental | MKENYCLQAALVCLGMLCHSHA | |||||

| 17 | 2160714 | carboxypeptidase Z precursor | 0.16 | secreted, experimental | MPPPPLLLLLTVLVVAAARP | |||||

| 18 | 2213913 | neuronal calcium channel alpha 1A subunit | 0.16 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | MKSIISLLFLLFLFIVVFALLG | |||||

| 19 | 182280 | EVI2 protein | 0.23 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MEHTGHYLHLAFLMTTVFSLSPGTKA | |||||

| 20 | 4336325 | small membrane protein 1 | 0.25 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 21 | 3982775 | insulin receptor binding protein GRB-IR | 0.26 | cell surface, mitochondrion and cytoplasm, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 22 | 6707925 | T calcium channel alpha1I subunit | 0.29 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 23 | 414928 | G protein-coupled receptor | 0.33 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | MTDKYRLHLSVADLLFVITLPFWAVDA | |||||

| 24 | 31442 | integrin beta 1 subunit precursor | 0.34 | cell surface, 1TM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 25 | 1663517 | membrane glycoprotein M6 | 0.34 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MLAWLGVTAFTSLPVYMLA | |||||

| 26 | 11559216 | MS4A6 | 0.34 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MMVLSLGIILASASFSPNFTQVTS | |||||

| 27 | 6434904 | tetraspanin TM4-C | 0.35 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MMILFNLLIFLCGAALLAVGIWV | |||||

| 28 | 6642960 | glycoprotein-associated amino acid | 0.39 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | MIHVKRCTPIPALLFTCISTLLMLVTS | |||||

| 29 | 386790 | cell surface glycoprotein | 0.39 | cell surface, 1TM, experimental | MRMATPLLMQALPMGALP | |||||

| 30 | 5457049 | protocadherin beta 7 | 0.46 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MEARVERAVQKRQVLFLCVFLGMSWAGA | |||||

| 31 | 337360 | receptor tyrosine kinase | 0.46 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MKPATGLWVWVSLLVAAGTVQP | |||||

| 32 | 516263 | adenylyl cyclase | 0.49 | cell surface, multiTM, prediction | MLPLPLTWAILAGLGTSLLQVILQVVI | |||||

| 33 | 5042232 | disintegrin-protease | 0.54 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | MLRGISQLPAVATMSWVLLPVLWLIVQTQA | |||||

| 34 | 9965402 | twisted gastrulation protein precursor | 0.56 | secreted, prediction | MKLHYVAVLTLAILMFLTWLPESLS | |||||

| 35 | 178250 | angiogenin | 0.57 | secreted and nuclear, experimental | MVMGLGVWLLVFVLGLGLTPPTLA | |||||

| 36 | 5457045 | protocadherin beta 5 | 0.57 | cell surface, 1TM, prediction | METALAKTPQKRQVMFLAILLLLWEAGSEA | |||||

| 37 | 3006228 | Zn-alpha2-glycoprotein | 0.58 | secreted, experimental | MVPVLLSLLLLLGPAVPQ | |||||

| 38 | 3127176 | sulfonylurea receptor 2B | 0.62 | cell surface, multiTM, experimental | MNAAIPIAAVLATFVTHAYA | |||||

| Intracellular proteins | ||||||||||

| 39 | 303616 | PIG-F | 0.13 | ER, multiTM, prediction | MHKRWVYSSLLISLSFMVFSWMA | |||||

| 40 | 37265 | TRAM protein | 0.14 | ER membrane, multiTM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 41 | 6911590 | calnexin | 0.14 | ER membrane, 1TM, experimental | MEGKWLLCML LVLGTAIVEA | |||||

| 42 | 307311 | neuroendocrine-specific protein C | 0.17 | ER membrane, multiTM, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 43 | 9502013 | cholinephosphotransferase 1 beta | 0.50 | microsome and nuclear, multiTM, experimental | MAPNSITLLGLAVNVVTTLVLISYC | |||||

| 44 | 6329074 | UDP-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase | 0.12 | golgi, 1TM typell, prediction | MRLRNGTVATALAFITSFLTLS | |||||

| 45 | 496369 | glucocerebrosidase | 0.32 | lysosomal, experimental | MEFSSPSREECPKPLSRVSIMAGSLTGLLLLQ | |||||

| 46 | 4164448 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase ASHI | 0.14 | mitochondrion, prediction | MQLFGFLAFMIFMCWVGDVYP | |||||

| 47 | 4689104 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase ASHI | 0.49 | mitochondrion, prediction | MQLFGFLAFMIFMCWVGD | |||||

| 48 | 388166 | Bax alpha | 0.15 | cytoplasmic, nuclear and mitochondrial, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 49 | 603074 | ATP:citrate lyase | 0.13 | cytoplasmic, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 50 | 2443338 | myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 | 0.14 | cytoplasmic, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 51 | 8671754 | DAZ associated protein 1 | 0.15 | cytoplasmic, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 52 | 1236915 | cyclin G2 | 0.17 | cytoplasmic, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 53 | 5442446 | thioltransferase | 0.19 | cytoplasmic, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 54 | 440306 | natural-killer enhancer protein | 0.20 | nuclear and cytoplasmic, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 55 | 2282030 | Arp2 | 0.27 | cytoplasmic, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 56 | 13591593 | RING finger protein with leucine | 0.51 | cytoplasmic, prediction | MKMSVILGIIHMLFGVSLS | |||||

| 57 | 7542723 | DHHC1 protein | 0.13 | nuclear, cytoplasmic, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 58 | 2924760 | CIRP (cold-inducible RNA-binding protein) | 0.12 | nuclear, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 59 | 510408 | DNA primase (p58 subunit) | 0.13 | nuclear, prediction | n.d. | |||||

| 60 | 565643 | hnRNP B1 protein | 0.51 | nuclear, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 61 | 7239366 | groucho-related protein 4 | 0.30 | nuclear, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| 62 | 521144 | ELAV-like neuronal protein 1 | 0.40 | nuclear, experimental | n.d. | |||||

| Localization unknown | ||||||||||

| 63 | 5410355 | insulin induced protein 2 | 0.17 | unknown, multiTM | MIRGVVLFFIGVFLALVLNLLQIQR | |||||

| 64 | 9963859 | PTD019 | 0.19 | unknown, 1TM | MRAFRKNKTLGYGVPMLLLIVGGSFG | |||||

| 65 | 4929220 | colon cancer-associated protein Mic1 | 0.44 | unknown, 0TM | n.d. | |||||

DISCUSSION

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, most proteins are guided into the secretory pathway by virtue of their signal peptides (Watts et al. 1983). Not surprisingly, the distributions of charged residues of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal sequences are remarkably similar in terms of net charge and in terms of the position of charged residues within the N-terminal region (von Heijne 1984). We postulated that this similarity was sufficient for E. coli to interchangeably use signal peptides encoded in human cDNA to direct the translocation of proteins across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane into the periplasmic space. To test our hypothesis, we created cDNA constructs where human cDNAs were cloned upstream of a β-lactamase gene with its own leader sequence deleted. Removal of the signal sequence causes the bacteria to produce an active enzyme that is neither secreted into the periplasm nor proteolytically processed (Kadonaga et al. 1984). Here, we found that replacement of the β-lactamase leader sequence with human signal peptide sequences was sufficient to confer protein secretion in E. coli. To successfully apply this strategy as a selection system for signal peptides encoded in cDNA libraries, there were several requirements. First, as the signal peptide is often (but not always) residing at the N-terminus of the pre-protein, it was necessary for us to synthesize cDNA representing these N-terminal regions in order to capture cDNA encoding real signal peptides. To accomplish this, we devised a cDNA synthesis strategy that enriched for the 5′ ends of mRNA transcripts (see Methods). Secondly, removal of the ATG start codon from β-lactamase was necessary, as it had been shown previously that short random sequences can functionally replace the secretion signal sequences of yeast invertase (Kaiser and Botstein 1986; Kaiser et al. 1987). The requirement for the ATG to be supplied by the fused cDNA eliminates some false positives which can arise from internal stretches of highly hydrophobic amino acids (Klein et al. 1996; Chen and Leder 1999). Finally, the cDNA fusion must be cloned in-frame with β-lactamase. Depending on the tissue source used for cDNA library construction, we find that approximately 0.5% to 1% of the recombinant clones survive carbenicillin challenge (data not shown). When randomly sampled clones from either antibiotic-challenged or unchallenged plates were compared for their ability to be secreted in HEK 293 cells, a significant enrichment for cDNA encoding secreted proteins was observed following selection. It is unclear why some clones, which encoded for fusion proteins that were secreted in E.coli, did not test positive in the HEK 293 cells. One possible explanation is that there may be sequences recognized by the prokaryotic organism that fail to be recognized by the more evolved eukaryotic signal recognition system. It is also conceivable that these cDNAs may encode for a functional signal peptide along with one or more transmembrane segments which anchor the β-lactamase fusion protein to the inner cell surface where it is inaccessible to the soluble assay substrate. Additionally, successful expression of the fusion protein in the HEK 293 cells requires the presence of a Kozak consensus sequence (Kozak 1986) on the cDNA, a requirement not necessary for expression in E. coli. Twenty-four of the 65 proteins cloned appear to be false positives (Table 2). Ten of these were endoplasmic reticulum, golgi, lysosomal, or mitochondrial proteins, which are likely to harbor signal sequences leading to its selection by signal trap methods. However, the remaining 14 proteins are clearly normally localized to the nucleus or cytosol, and are not known to contain any signal peptide sequences. It is unknown how these normally intracellular proteins when partly fused to β-lactamase became exported to the extracellular space. Perhaps overexpression of these constructs under a strong CMV promoter led to a non-signal peptide-dependent secretory mechanism. Alternatively, short internal hydrophobic stretches flanked by an internal methionine residue may have masqueraded as signal sequences for both the E. coli and the HEK 293 cells. Still, the false positive rate observed here (36.9%) is lower than those observed with the epitope tagging (57.7%) and CD4 fusion (58%) signal trap methods (Imai et al. 1996; Shirozu et al. 1996). Another advantage of this procedure is that it appears to be more sensitive than those previously described. With E. coli, depending on the human tissue source used to synthesize cDNA, typically 0.5%–1% of all clones tested are selected. With the direct use of mammalian cells, the selection rate is much lower at 0.04% (Kojima and Kitamura 1999), and even lower at 0.0025% using yeast (Klein et al. 1996). If an estimated 10% of all human proteins are secreted or transmembrane, these methods appear to be oversensitive and may exclude the identification of many signal peptide-containing proteins. Indeed, none of the cDNAs isolated using the cytokine receptor trap encoded transmembrane domain sequences (Kojima and Kitamura 1999). One setback for the selection in E. coli, however, is that it is only capable of identifying proteins exported through signal peptide-based mechanisms, and any polypeptide in a mammalian cell requiring posttranslational modifications for secretion may be systematically missed.

In summary, we conclude that this is a convenient procedure to generate libraries of clones enriched for secreted and cell surface proteins. Due to the simplicity of using an E. coli system to screen for mammalian signal peptides, we believe this method offers a powerful way to quickly identify novel secreted and membrane proteins. These results have also furthered our understanding of the striking similarities in signal peptide recognition mechanisms between human and gram-negative bacteria. Today, even with the availability of the complete human genome sequence, major problems are still being encountered with the high errors associated with prediction inaccuracies and with extracellular proteins lacking signal peptides (Antelmann et al. 2001). It is our hope that large-scale sequencing of selected clones will lead to the identification of secreted and receptor proteins missed by sequence-based bioinformatics approaches.

METHODS

Vector Constructs

pBK-CMV (kanamycin-resistant) was purchased from Stratagene. To remove the first ATG following the CMV promoter, pBK-CMV was digested with NheI and EcoRI. A fragment generated by PCR with primers 5′GATCGATCGAATTCTTCCACACAATATACGAG and 5′GTCAGATCCGCTAGCCGCAATTAC using pBK-CMV as template was digested with the same enzymes and ligated in to form pBK-CMV-noATG. The β-lactamase gene was PCR-amplified from plasmid pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) using primers 5′ACTTACCTGGTACCTTACCAATGCTTAATCAG and 5′GTGTGGAAGAAT TCATGAGTATTCAACATTTC. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and KpnI and then ligated into pBK-CMV-noATG to form pBK-CMV-β-lactamase. To remove the leader sequence on pBK-CMV-β-lactamase, PCR was performed using 5′GTGTGGAAGAATTCATGCACCCAGAAACGCTG in lieu of 5′GTGTGGAAGAATTCATGAGTATTCAACATTTC in the above step. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and KpnI, and ligated into pBK-CMV-noATG to form pBK-CMV-leaderless-β-lactamase. To allow for N-terminal cDNA fusion to the leaderless β-lactamase gene, PCR was performed with 5′TAACTGTGGCGGCCGCAGGAGGTGGACACCCAGAAACGCTGGTG and 5′ACTTACCTGGTACCTTACCAATGCTTAATCAG using pBK-CMV-β-lactamase as template. The PCR product was digested and cloned into the NotI and KpnI sites of pBR-CMV-noATG to form pBK-CMV-fusion. As positive control, a NotI–EcoRI-ended double-stranded oligonucleotide representing the β-lactamase leader sequence was synthesized (5′AATTCATGAGTATTCAACATTTCCGTGTCGCCCTTATTCCCTTTTTTGCGGCCATTTTGCCTTCCTGTTTTTGCTGC and 5′GGCCGCAGCAAAAACAGGAAGGCAAAATGCCGCAAAAAAGGGAATAAGGGCGACACGGAAATGTTGAATACTCATG). For negative control, a clone containing the 5′ UTR and coding region of the first 150 amino acids of HSPCA (GenBank 32487) was PCR-amplified using primers 5′AGTGTGGTGGAATTCCAGTTGCTTCAGCGTCCCGG and 5′ACTCCACCTCCTGCGGCCGCCACAGTTACTTTCTCAGCAACC. The amplified product was subcloned inframe into the EcoRI and NotI sites of pBK-CMV-fusion to form pBK-CMV-HSP. The coding sequence for the human CD4 precursor was amplified from the start to the stop codon using the primers 5′TCTGGGTGTCCACCTCCTGCGGCCGCAATGGGGCTACATGTCTTCTG and 5′TGTGTGGAAGAATTCATGAACCGGGGAGTCCCTTTTAGG. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and NotI and cloned into the same sites of pBK-CMV-fusion to form pBK-CMV-CD4.

5′ Bias cDNA Synthesis and Library Construction

Total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen). mRNA was selected using Oligotex beads (QIAGEN). 5′-biased cDNA ends were generated as described (Guegler et al. 2000). Briefly, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using Dynabeads Oligo dT(25) (Dynal Biotech) following the manufacturer's protocols using 1.5μg of mRNA. The beads were then washed twice in TE and resuspended in first-strand cDNA synthesis buffer with RnaseH-free MMLV (Promega) in the presence of a random primer (5′GCGGCCGCGGCCGCNNNNNNNNN) flanked by a NotI site. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized using the standard Gubler-Hoffman strand replacement method (Gubler and Hoffman 1983). Following this, the Dynal-Oligo dT beads were removed, and residual soluble cDNA was blunt-ended and ligated to EcoRI adaptors (Stratagene). cDNA was digested with NotI, size-selected for fragments >500 bp, and ligated into the EcoRI and NotI sites of pBK-CMV-fusion. The ligation mix was electroporated into DH10B cells and plated on agar plates supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg/mL) and IPTG (1 mM) or kanamycin (30 μg/mL).

DNA Purification and Cell Transfection

Selected recombinant clones were inoculated into 1.0 mL of Terrific Broth (TB) containing 0.4% glycerol and 100 μg/mL carbenicillin, and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 300 rpm. Plasmid DNA was prepared using QIAwell 96 Ultra Plasmid Kits (QIA-GEN). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (ATCC) were maintained in DME plus 10% FCS and glutamine, 1× antibiotics and antimycotics (Invitrogen). For transfection, cells were trypsinized and seeded into 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 40,000 cells/well in 100 μL phenol-red free DME/10% FCS (Invitrogen). The following day, transfection cocktails were assembled in 96-well plates. The purified plasmid DNA (∼200 ng in 10 μL/well) was diluted with 15μL OPTI-MEM I medium (Invitrogen) to a volume of 25μL/well. In separate plates, 1 μL LF2000 Reagent (Life Technologies) was diluted into 25μL/well with OPTI-MEM I. The 25μL diluted LF2000 Reagent was then combined with the 25μL diluted DNA, mixed briefly, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The DNA-LF2000 reagent complexes were then added directly to each well. Cells were also transfected with the control plasmids expressing a leaderless β-lactamase gene, the wild-type β-lactamase, CD4 fusion to the leaderless β-lactamase, or an HSP fusion to β-lactamase. β-lactamase activities were measured 24 h following transfection as described below.

β-Lactamase Assay

Lactamase activity was determined by measuring hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate nitrocefin (Calbiochem; Smith et al. 1987). Twenty-four h following transfection, 90 μL of cell culture media was removed for assay. The removed media was replaced by 90 μL PBS, and cells were lysed by three cycles of repeated freezing and thawing. The cell media (90 μL) and cell lysate (90 μL) were assayed at 37°C with 100 μM nitrocefin, 0.5 mM oleic acid (Sigma) in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Absorbance at 486 nm was determined over 20 min in a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Automated DNA sequencing was performed using MegaBACE DNA sequencers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Forward and reverse sequence reads from the cloned inserts were assembled using Phrap (Ewing et al. 1998). Clone sequences were compared against NCBI's Genpept database using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990). Detection of transmembrane domains and signal peptides was performed using an in-house collection of Hidden Markov Models, GCG Spscan (Genetics Computer Group 1999), and TMHMM (Krogh et al. 2001).

Acknowledgments

We thank Karl Guegler, Jonathan Wang, Preeti Lal, and Janice AuYoung for helpful suggestions.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.1000903.

Footnotes

Article published online before print in July 2003.

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelmann, H., Tjalsma, H., Voigt, B., Ohlmeier, S., Bron, S., van Dijl, J.M., and Hecker, M. 2001. A proteomic view on genome-based signal peptide predictions. Genome Res. 11: 1484-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. and Leder, P. 1999. A new signal sequence trap using alkaline phosphatase as a reporter. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 1219-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B., Hillier, L., Wendl, M.C., and Green, P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8: 175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetics Computer Group. 1999. Wisconsin Package Version 10, Madison, WI.

- Gubler, U. and Hoffman, B.J. 1983. A simple and very efficient method for generating cDNA libraries. Gene 25: 263-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guegler, K., Tan, R., and Rose, M.J. 2000. Methods and compositions for producing 5′ enriched cDNA libraries. In United States Patent and Trademarks Office. Patent No. 6,083,727. Incyte Pharmaceuticals, Inc., USA.

- Hoffman, C.S. and Wright, A. 1985. Fusions of secreted proteins to alkaline phosphatase: An approach for studying protein secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 82: 5107-5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai, T., Yoshida, T., Baba, M., Nishimura, M., Kakizaki, M., and Yoshie, O. 1996. Molecular cloning of a novel T cell-directed CC chemokine expressed in thymus by signal sequence trap using Epstein-Barr virus vector. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 21514-21521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, K.A., Collins-Racie, L.A., Colbert, M., Duckett, M., Golden-Fleet, M., Kelleher, K., Kriz, R., LaVallie, E.R., Merberg, D., Spaulding, V., et al. 1997. A genetic selection for isolating cDNAs encoding secreted proteins. Gene 198: 289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadonaga, J.T., Gautier, A.E., Straus, D.R., Charles, A.D., Edge, M.D., and Knowles, J.R. 1984. The role of the β-lactamase signal sequence in the secretion of proteins by Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 259: 2149-2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C.A. and Botstein, D. 1986. Secretion-defective mutations in the signal sequence for Saccharomyces cerevisiae invertase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6: 2382-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C.A., Preuss, D., Grisafi, P., and Botstein, D. 1987. Many random sequences functionally replace the secretion signal sequence of yeast invertase. Science 235: 312-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R.D., Gu, Q., Goddard, A., and Rosenthal, A. 1996. Selection for genes encoding secreted proteins and receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93: 7108-7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T. and Kitamura, T. 1999. A signal sequence trap based on a constitutively active cytokine receptor. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 487-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. 1986. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 44: 283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G., and Sonnhammer, E.L. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305: 567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirozu, M., Tada, H., Tashiro, K., Nakamura, T., Lopez, N.D., Nazarea, M., Hamada, T., Sato, T., Nakano, T., and Honjo, T. 1996. Characterization of novel secreted and membrane proteins isolated by the signal sequence trap method. Genomics 37: 273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H., Bron, S., Van Ee, J., and Venema, G. 1987. Construction and use of signal sequence selection vectors in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 169: 3321-3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro, K., Tada, H., Heilker, R., Shirozu, M., Nakano, T., and Honjo, T. 1993. Signal sequence trap: A cloning strategy for secreted proteins and type I membrane proteins. Science 261: 600-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne, G. 1984. Analysis of the distribution of charged residues in the N-terminal region of signal sequences: Implications for protein export in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 3: 2315-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne, G. 1985. Signal sequences. The limits of variation. J. Mol. Biol. 184: 99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, C., Wickner, W., and Zimmermann, R. 1983. M13 procoat and a preimmunoglobulin share processing specificity but use different membrane receptor mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 80: 2809-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]