Abstract

This protocol describes a pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the clinical and cost effectiveness of arthroscopic and open surgery in the management of rotator cuff tears. This trial began in 2007 and was modified in 2010, with the removal of a non-operative arm due to high rates of early crossover to surgery.

Cite this article: Bone Joint Res 2014;3:155–60.

Keywords: Shoulder, Rotator cuff, Tendon, Tears, Surgery, Arthroscopy

Introduction

In 2000, an assessment of the prevalence and incidence of consultations for shoulder problems in UK primary care estimated the annual prevalence to be 2.4%, with the rate increasing linearly with age.1 It is estimated that disorders of the rotator cuff account for between 30% and 70% of the shoulder pain cases that are reported.2,3 The clinical evidence available, regarding both the natural history and management of rotator cuff tears, is limited and conflicting; most reports are small scale, (< 50 cases), single-centre, retrospective cohort studies.4-11

Rotator cuff tears can be treated both surgically (arthroscopic and open) and non-surgically (for example by injection and exercises). Traumatic tears are uncommon: most patients present through age-related degeneration of tendon attachment to bone at the proximal humerus. Surgical repair may be considered for patients with persistent symptoms who fail to respond to rest and conservative care. Such non-operative care will usually include physiotherapy and glucocorticoid injections into the shoulder.

A rotator cuff repair operation aims to re-attach the tendons to the bone. The repair may also include an acromioplasty, where overhanging bone and soft tissue above the tendon are excised, with the aim of creating more space for the rotator cuff tendons to move freely.

In general, two approaches are available for surgical repair:

Open/mini-open surgery involves the rotator cuff being repaired under direct vision through an incision in the skin.

Arthroscopic surgery involves the repair being performed through arthroscopic portals.

Proponents of arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery suggest that the procedure may have advantages over standard open techniques, in that the resulting trauma to the deltoid muscle and overlying soft tissue is reduced. Arguably, this causes less post-operative patient discomfort, together with earlier return of movement. However, the success of the repair depends on the ability of the surgeon to achieve a secure attachment of tendon to bone. This may be more easily and reliably achieved by open/mini-open surgery. Other potential disadvantages of the arthroscopic approach include increased technical difficulty and longer time in theatre. Only a few, small, non-randomised studies have directly compared procedures and therefore there is a need to compare the outcome of the two surgical techniques.12

The primary objective of this study is to conduct a pragmatic multicentre randomised clinical trial to obtain good quality evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic versus open surgical repair for the treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tears.

Materials and Methods

Design

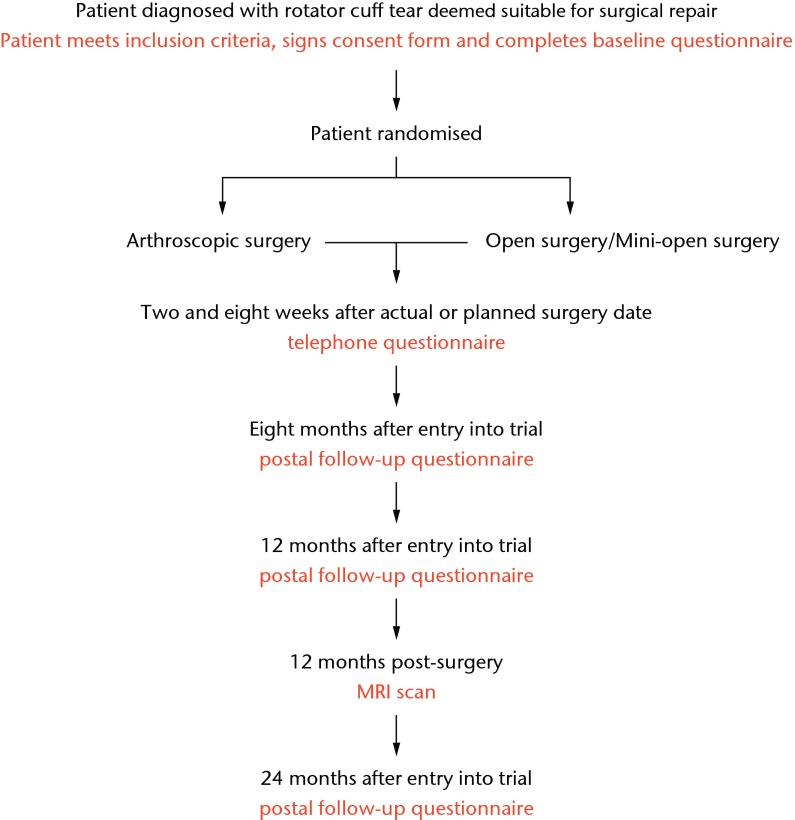

At the outset of the UKUFF trial in 2007, a three-way parallel group randomised trial began comparing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair surgery with open or mini-open rotator cuff repair surgery with a rest-then-exercise programme of non-operative care [UKUFF Original REC Version Number 07/Q1606/49]. Figure 1 presents the original version as a flowchart.

Fig. 1.

Original trial flow chart.

The trial was adapted and reconfigured by the funder in 2009, (after consultation with the trial steering and data monitoring committees), into a two-way parallel group RCT, due to a high rate of crossover of patients (85%) from the rest-then-exercise programme to surgery (UKUFF Reconfigured REC Reference Number 10/H0402/24). A total of 87 patients were carried through to the subsequent reconfigured trial. After the reconfiguration, it was calculated that a further 180 patients should be recruited and followed up for two years as per the original protocol (providing a total of 267 patients treated with surgery). It is the reconfigured design that is presented in this protocol.

UKUFF (reconfigured) is a pragmatic multicentre study involving 20 surgeons from 16 UK centres. It includes patients over 50 years of age, with a diagnosis of a full thickness rotator cuff tear who are deemed eligible for surgery. Patients are randomised to either open or arthroscopic repair, while the surgeons perform their usual and preferred surgical technique using one of these approaches. Patients are followed up with telephone and postal questionnaires for 24 months, and an MRI or USS (Ultrasound Scan) 12 months after their surgery. The primary outcome is the Oxford Shoulder Score at 24 months.13 The study is led by clinicians (both surgeons and physiotherapists), methodologists, statisticians and health economists.

Surgeon eligibility

Participating surgeons require a ‘minimum level of expertise’ for the types of surgery undertaken. For both surgical techniques, only consultant orthopaedic shoulder surgeons with a minimum of two years’ experience in consultant practice can participate. For those surgeons performing both arthroscopic surgery and open surgery, only those who have performed a minimum of five cases per year are considered eligible. The participating surgeons represent a cross-section of high, medium and low volume practitioners undertaking both arthroscopic and open surgery.

Recruitment and treatment allocation

Support from local research networks is used, where possible, to help with patient identification, recruitment and with obtaining any required data from patient notes. The eligibility of the patient is confirmed by the local consultant orthopaedic surgeon.

Patient eligibility

The patient is eligible for the study if:

Aged at least 50 years old;

Suffer from a degenerative rotator cuff tear;

Have a full thickness rotator cuff tear;

Rotator cuff tear diagnosed using MRI or ultrasound scan;

Able to consent.

The patient is excluded if any of the following apply:

Previous surgery on affected shoulder;

Dual shoulder pathology;

Traumatic tear;

Significant problems in the other shoulder;

Rheumatoid arthritis/systemic disease;

Significant osteoarthritis problems;

Significant neck problems;

Cognitive impairment or language issues;

Unable to undergo an MRI scan for any reason.

There is no formal age limit. However, patients aged 85 years and over are not expected to be eligible to participate. Consent is obtained either locally, by a research nurse, or remotely by the study office in Oxford. Only when the consent form and the baseline questionnaire have been returned is the participant entered into the trial and randomised to one of the surgical options. Randomisation is by computer allocation at the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen. Allocation was minimised using surgeon, age and size of tear. After randomisation, the participant is irrevocably part of the trial for the purpose of the research, irrespective of what occurs subsequently.

Patients are free to withdraw at any time without consequence to the health care they receive.

Randomised surgery

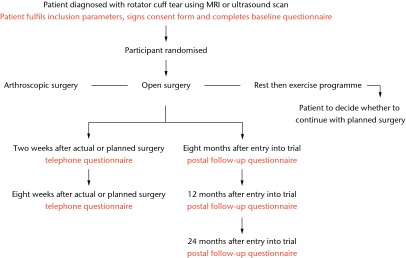

Details of the surgical technique used (including method of repair and theatre equipment used, e.g. types of suture) are recorded on a standard form, as are the size of the tear, the appearance of the tendons involved, and the ease and the completeness of the repair. If circumstances dictate that the allocated surgical technique cannot be carried out, then any alternative procedure is recorded. The surgeon contacts the study office if their patient is unwilling or unable to have the operation on the arranged date. Patient progress through the study is detailed in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

UKUFF trial flow chart.

Data collection and processing

Outcome assessments involve patient-completed questionnaires and 12-month post-surgery imaging.

Questionnaires

A combination of the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS),13 the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI),14 the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5)15 and the EQ-5D16 is used to assess functional outcome and patient-reported quality of life. These assess a range of symptoms often experienced with rotator cuff tears, e.g. pain, weakness and a loss of function. Outcome assessments are conducted by participant self-completion questionnaires and, as such, interviewer bias and clinical-rater bias are avoided. This form of outcome measurement has consistently performed well in comparison with clinician-based assessments and general health status measures. All participants, including those who withdraw from their allocated intervention but who still wish to be involved in the study, are followed up with analysis based on the intention to treat principle.

Participants will receive questionnaires at the following time points:

Baseline questionnaire – completed before randomisation;

Two and eight weeks post treatment – questionnaire completed over the phone;

Eight, 12 and 24 months post-randomisation.

The baseline, 12- and 24-month post-randomisation questionnaires also collect information to inform a cost-effectiveness element. Questions relating to information on primary care consultations, other consultations, out-of-pocket costs and work impact of the intervention received, are included. The study office in Aberdeen will contact and follow up participants whose questionnaires have not been returned.

Post-operative imaging

High rates of re-rupture of the rotator cuff tear (20% to 54%) have been reported after surgery, with some reporting a significant correlation between re-rupture and poor outcome.17 Rates of re-rupture or repair failure may differ between the two surgical techniques. For this reason, participants will undergo an MRI or USS at 12 months post operation to assess the state of the rotator cuff repair. These are arranged by the study office in Oxford and performed locally. The images are collected centrally and read by an independent consultant radiologist blind to the type of surgery performed. The results of the scan are not reported to the participating surgeons. Incidental abnormalities of clinical significance are reported to the surgeon.

Analysis

Statistical analyses are based on randomisation of patients, irrespective of subsequent compliance with the randomised intervention. The principal comparisons will be all those allocated arthroscopic surgery versus all those allocated open surgery. The analyst will be blinded to the allocation.

Measure of outcome

The primary outcome measure used will be the OSS at 24 months after randomisation.

The primary measure of cost-effectiveness will be the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year gained.

Secondary outcome measures include:

OSS at 12 months after randomisation;

EQ-5D16 at eight, 12, 24 months after randomisation;

MHI-515 at eight, 12, 24 months after randomisation;

SPADI14 at eight, 12, 24 months after randomisation;

Participant’s rating of how pleased they are with shoulder symptoms at 12, 24 months after randomisation;

Participant’s view of state of shoulder at eight, 12, 24 months after randomisation;

Surgical complications (intra- and post-operative) at two and eight weeks post surgery and at 12 and 24 months after randomisation;

Net health care costs at two weeks, 12 and 24 months after randomisation; out-of-pocket costs and work impact.

Planned subgroup analyses

i) Size of tear (small/medium versus large/massive); ii) Age < or equal to 65 or > 65.

Stricter levels of statistical significance (p < 0.01) will be used in subgroup analyses reflecting their exploratory nature and the multiple testing involved.

Statistical analysis

Reflecting the possible clustering in the data, the outcomes will be compared using multilevel models, with adjustment for minimisation variables and participant baseline values. Statistical significance is set at the 2.5% level, with corresponding confidence intervals. All participants will remain in their allocated group for analysis (intention to treat). Per-protocol analysis will also be performed.

Economic evaluation

A cost-effectiveness analysis will be performed. A simple patient resource-use questionnaire at baseline and at 12 and 24 months post randomisation is used to obtain information on primary care consultations, other consultations, out-of-pocket costs, work impact of the intervention received and return to work. Unit costs will come from national sources and participating hospitals. The patient questionnaire is also used to administer the EQ-5D. The main health economic outcome is within-trial and extrapolated quality-adjusted life years, estimated using the EQ-5D.

Incremental cost effectiveness will be calculated as the net cost per quality-adjusted life year gained, for arthroscopic surgery versus open surgery. Power calculations (see following section) have been based on clinical rather than cost effectiveness outcomes, which will be estimated rather than used in hypothesis testing. Cost-effectiveness ratios and net-benefit statistics will be calculated. We will report within-trial cost-effectiveness and explore if the trial produces sufficient evidence to plausibly model future quality of life or costs (e.g. based on projected failure rates). We will also extrapolate long-term cost effectiveness beyond the trial period.

An important component of this trial will be assessment of cost. Therefore, an accurate record of procedures at each of the proposed centres is essential. To evaluate costs of each type of surgery, information from the operating theatres will be collected. Theatre managers will be contacted and visited at each site. Resources used, equipment costs and standard procedures for rotator cuff repairs will be recorded. Per-case information will also be analysed during the final analysis. A checklist of equipment, consumables, implants, time and staff used during each case will be completed by theatre staff. Information from theatres will be collected by the Oxford UKUFF office and will be used in a cost comparison between the arthroscopic and open surgery.

Sample size and feasibility

Sample size sought

The sample size was designed to detect a difference in OSS score of 0.38 of a standard deviation (sd) for the comparison of arthroscopic versus open surgery. This was based on our experience of using and developing the OSS score in a variety of settings, from which a three-point difference (0.33 of a sd) would be deemed a clinically important change. Attrition is expected to be low (10%), as are the effects of clustering of outcomes18,19(intra cluster correlation (ICC) less than 0.03). While we did not have a direct estimate from a shoulder trial, other orthopaedic datasets available to our team supported this low ICC estimate. Both of these factors required the sample size to be inflated, however, the primary analysis will be adjusted for baseline OSS score which conversely allows the sample size to be decreased by a factor of 1-correlation squared.20 Our previous studies showed that the correlation in the OSS score pre surgery to six months post surgery in patients similar to potential trial participants was 0.57. Assuming a conservative correlation of 0.5 implied that the sample size could be reduced by 25%, and still maintains the same power. Therefore, a study with a total of 267 participants was considered sufficiently powered to detect a clinically important change in each comparison, assuming attrition and clustering accounted for approximately 25% of variation in the data.

Organisation

Trial Timeline

The trial began in December 2007 and was stopped in December 2009 to allow for reconfiguration. Funding approval of the reconfiguration was given in January 2010 and revised research ethics approval was granted in April 2010. In May 2010, recruitment started to the reconfigured design. The final follow-up assessment was planned for December 2013. Analysis and write up are planned for January 2014 to July 2014, with publication and dissemination from August 2014 onwards.

Central organisation of the study

Oxford co-ordinates the site-specific and clinical concerns, while Aberdeen houses the database and randomisation systems. The study is overseen by an independent Trial Steering Committee and an independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Protocol amendments

Small changes have been made to the protocol over time, to reflect changes in points of outcome data collection and recruitment procedures. Some changes have been made in response to alterations in waiting times for surgery in the NHS that occurred during the trial period. Support for individual centres also changed after the inception of the NIHR in the UK and the provision of a regional network of research support through the UK Comprehensive Research Network (UKCRN).

Publication

The investigators will be involved in reviewing drafts of the manuscripts, abstracts, press releases and any other publications arising from the study. Authors will acknowledge that the study was funded by the NIHR HTA programme. Authorship will be determined in accordance with the ICMJE guidelines and other contributors will be acknowledged. The main report will be drafted by the UKUFF Management Group, and the final version will be agreed by the Trial Steering Committee before submission for publication, on behalf of the UKUFF collaborators.

Trial status

UKUFF completed recruitment in February 2012, with follow-up completed in January 2014. Production of the monograph is planned for July 2014.

Trial sponsorship and registration

Trial co-sponsors are The University of Oxford, Joint Research Office, Churchill Hospital, Headington, Oxford and University of Aberdeen, University Office, King’s College, Regent Walk, Aberdeen.

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN): ISRCTN97804283.

Acknowledgement: Feedback on trial design and implementation and support for the trial have been obtained over a protracted period from a large number of people, including:

Past trial coordinators: Dr S. Breeman, Dr J. Murdoch, Dr J. Eldridge, Miss L. Davies

Trial Steering Committee: Professor J. Blazeby (Chair), Mr D. Stanley, Dr A. Cook, Ms J. Gibson, Major General D. Farrar Hockley and Professor J. Fairbank

Data Monitoring Committee: Professor R. Emery (Chair), Professor J. Lewis and Dr R. Morris.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme (project number 05/47/02). J. L. Rees has received a grant from Oxford University which is related to this paper. J. Dawson reports that Oxford University has received a grant from HTA which is related to this paper, as well as a study grant.

Footnotes

Author contributions:A. J. Carr: Design and development of study protocol, Wrote, read, commented on and approved final manuscript

J. L. Rees: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

C. R. Ramsay: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

J. Moser: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

C. D. Cooper: Design and development of study protocol, Wrote, read, commented on and approved final manuscript

D. J. Beard: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

R. Fitzpatrick: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

A. Gray: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

J. Dawson: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

H. Bruhn: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

M. K. Campbell: Design and development of study protocol, Read, commented on and approved final manuscript

ICMJE Conflict of Interest:None declared

References

- 1.Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, et al. Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell C, Adebajo A, Hay E, Carr A. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ 2005;331:1124–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macfarlane GJ, Hunt IM, Silman AJ. Predictors of chronic shoulder pain: a population based prospective study. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1612–1615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi, K. Mini-Open Rotator Cuff Repair: An Updated Perspective. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2001;83-A:764–772 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Demazière A. Arthroscopic debridement versus open repair for rotator cuff tears. A prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1993;75-B:416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber SC. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy 1999;15:126–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melillo AS, Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD. Massive rotator cuff tears: debridement versus repair. Orthop Clin North Am 1997;28:117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordasco FA, Backer M, Craig EV, Klein D, Warren RF. The partial-thickness rotator cuff tear: is acromioplasty without repair sufficient? Am J Sports Med 2002;30:257–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motycka T, Lehner A, Landsiedl F. Comparison of debridement versus suture in large rotator cuff tears: long-term study of 64 shoulders. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004;124:654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg BA, Smith K, Jackins S, Campbell B, Matsen FA 3rd. The magnitude and durability of functional improvement after total shoulder arthroplasty for degenerative joint disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001;10:464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earnshaw P, Desjardins D, Sarkar K, Uhthoff HK. Rotator cuff tears: the role of surgery. Can J Surg 1982;25:60–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youm T, Murray DH, Kubiak EN, Rokito AS, Zuckerman JD. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comparison of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005;14:455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson J, Rogers K, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The Oxford shoulder score revisited. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009;129:119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res 1991;4:143–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware E, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA). J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:903–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.EuroQol Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life Health Policy 1990;16:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harryman DT 2nd, Mack LA, Wang KY, et al. Repairs of the rotator cuff. Correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1991;73-A:982–989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyle, R. Statistical strategies for small sample research. London: Sage Publications Inc, 1999.

- 19.Campbell M, Grimshaw J, Steen N. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised trials. Changing Professional Practice in Europe Group (EU BIOMED II Concerted Action). J Health Serv Res Policy 2000;5:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein, H. Multilevel statistical models 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold,1995.