Abstract

This paper outlines six important tasks for psychiatry today, which can be put in short as:

Spread and scale up services;

Talk;

Science,

Psychotherapy;

Integrate; and

Research excellence.

As an acronym, STSPIR.

-

Spread and scale up services: Spreading mental health services to uncovered areas, and increasing facilities in covered areas:

- Mental disorders are leading cause of ill health but bottom of health agenda;

- Patients face widespread discrimination, human rights violations and lack of facilities;

- Need to stem the brain drain from developing countries;

- At any given point, 10% of the adult population report having some mental or behavioural disorder;

- In India, serious mental disorders affect nearly 80 million people, i.e. combined population of the northern top of India, including Punjab, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh;

- Combating imbalance between burden of demand and supply of efficient psychiatric services in all countries, especially in developing ones like India, is the first task before psychiatry today. If ever a greater role for activism were needed, this is the field;

- The need is to scale up effective and cost-effective treatments and preventive interventions for mental disorders.

-

Talk: Speaking to a wider audience about positive contributions of psychiatry:

- Being aware of, understanding, and countering, the massive anti-psychiatry propaganda online and elsewhere;

- Giving a firm answer to anti-psychiatry even while understanding its transformation into mental health consumerism and opposition to reckless medicalisation;

- Defining normality and abnormality;

- Bringing about greater precision in diagnosis and care;

- Motivating those helped by psychiatry to speak up;

- Setting up informative websites and organising programmes to reduce stigma and spread mental health awareness;

- Setting up regular columns in psychiatry journals around the globe, called ‘Patients Speak’, or something similar, wherein those who have been helped get a chance to voice their stories.

-

Science: Shrugging ambivalence and disagreement and searching for commonalities in psychiatric phenomena;

- An idiographic orientation which stresses individuality cannot, and should not, preclude the nomothetic or norm laying thrust that is the crux of scientific progress.

- The major contribution of science has been to recognize such commonalities so they can be researched, categorized and used for human welfare.

- It is a mistake to stress individuality so much that commonalities are obliterated.

- While the purpose and approach of psychiatry, as of all medicine, has to be humane and caring, therapeutic advancements and aetiologic understandings are going to result only from a scientific methodology.

- Just caring is not enough, if you have not mastered the methods of care, which only science can supply.

-

Psychotherapy: Psychiatrists continuing to do psychotherapy:

- Psychotherapy must be clearly defined, its parameters and methods firmly delineated, its proof of effectiveness convincingly demonstrated by evidence based and controlled trials;

- Psychotherapy research suffers from neglect by the mainstream at present, because of the ascendancy of biological psychiatry;

- It suffers resource constraints as major sponsors like pharma not interested;

- Needs funding from some sincere researcher organisations and altruistic sponsors, as also professional societies and governments;

- Psychotherapy research will have to provide enough irrefutable evidence that it works, with replicable studies that prove it across geographical areas;

- It will not do for psychiatrists to hand over psychotherapy to clinical psychologists and others.

-

Integrate approaches: Welcoming biological breakthroughs, while supplying psychosocial insights:

- Experimental breakthroughs, both in aetiology and therapeutics, will come mainly from biology, but the insights and leads can hopefully come from many other fields, especially the psychosocial and philosophical;

- The biological and the psychological are not exclusive but complementary approaches;

- Both integration and reductionism are valid. Integration is necessary as an attitude, reductionism is necessary as an approach. Both the biological and the psychosocial must co-exist in the individual psychiatrist, as much as the branch itself.

-

Research excellence: Promoting genuine research alone, and working towards an Indian Nobel Laureate in psychiatry by 2020:

- To stop promoting poor quality research and researchers, and to stop encouraging sycophants and ladder climbers. To pick up and hone genuine research talent from among faculty and students;

- Developing consistent quality environs in departments and having Heads of Units who recognize, hone and nurture talent. And who never give in to pessimism and cynicism;

- Stop being satisfied with the money, power and prestige that comes by wheeling-dealing, groupism and politicking;

- Infinite vistas of opportunity wait in the wings to unfold and offer opportunities for unravelling the mysteries of the ‘mind’ to the earnest seeker. Provided he is ready to seek the valuable. Provided he stops holding on to the artificial and the superfluous.

Keywords: Biological breakthroughs, Commonalities in psychiatry, Indian Nobel Laureate, Integrate, Positive contributions of psychiatry, Psychosocial insights, Psychotherapy, Research excellence, Scale up services, Science, Stigma, Talk

Introduction

A revised and substantially updated version of an earlier paper (Singh, 2007[93]) that also served as a seed paper for a symposium with the same name held at the 2013 Annual Conference of the Indian Psychiatric Society was due. Hence, this paper. It was also proper to publish an edited and peer reviewed version of the proceedings of that symposium in the Mens Sana Monographs. Hence, this Symposium.

While each one of us has his own special concerns and would like to give his own take on what he considers the task before psychiatry today (see, for example, thought provoking ones by Roberts, 2009[82], 2013[81]; Frances, 2013[22]), I want to highlight some critical areas for your consideration which are likely to be common concerns for us all.

I divide them into six tasks to be performed, five of concern to all psychiatrists everywhere (with the first of special concern to India and other developing countries), and the sixth of special concern to Indian psychiatrists and psychiatry. These six important tasks for psychiatry today are:

Spread mental health services to uncovered areas, and increase facilities in covered areas, i.e., Spread and scale up services;

Speak to a wider audience about positive contributions of psychiatry, i.e., Talk;

Shrug ambivalence and disagreement and search for commonalities in psychiatric phenomena, i.e., Science;

Psychiatrists must continue to do psychotherapy, i.e., Psychotherapy;

Welcome biological breakthroughs, while supplying psychosocial insights, i.e., Integrate approaches;

Promote genuine research alone, and working towards an Indian Nobel Laureate in psychiatry by 2020, i.e., Research excellence.

In short:

Spread/scale up services;

Talk;

Science,

Psychotherapy;

Integrate approaches; and

Research excellence.

As an acronym, STSPIR.

STSPIR is the mantra forward. Let us see what this entails.

The First Task: Spreading Mental Health Services to Uncovered Areas, and Increasing Facilities in Covered Areas, i.e., Spread and Scale up Services

The urgent and crying need for psychiatry is to spread mental health services to uncovered areas, especially in developing countries. As also reach out to under-covered areas in developed populations. And strengthen mental health services in areas well covered. In other words, spread and scale up services.

Why?

Leading cause of ill health but bottom of health agenda

Mental and neurological disorders are the leading cause of ill health and disability globally (WHO, 2001[106]), but there is an appalling lack of global interest from governments and NGOs (Patel, 2008[74]). Globally, mental health is widely neglected and marginalized (Saraceno and Dua, 2009[84]). Mental disorders constitute a huge global burden of disease, but there is a large treatment gap, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (Eaton et al., 2011[20]; Petersen, Lund and Stein, 2011[77]).

Mark the word ‘globally’. It signifies that the phenomenon is not restricted to some countries although low-income and middle-income countries bear its greatest brunt.

Psychiatry and mental health services are near bottom of the agenda in most societies, both awareness wise and health budget allotment wise. Amongst global health conditions, while mental health problems account for an estimated 14% (WHO, 2008[107]), they receive less than 1% of most countries’ healthcare budget (Chambers, 2010[13]). The poorest countries spend the lowest percentages of their overall health budgets on mental health (Saxena et al., 2007[86]). Talking of India, mental health is part of the general health services, but carries no separate budget (Khandelwal et al., 2004[46]). Populations with high rates of socioeconomic deprivation have the highest need for mental health care, but the lowest access to it (Saxena et al., 2007[86]).

In other words, mental disorders are leading cause of ill health but are at the bottom of health agenda.

Widespread discrimination, human rights violations and lack of facilities

What does being bottom of the health agenda entail? Stigma, neglect and human rights violations.

Stigma over mental disorder and neglect of psychiatric patients go hand in hand, and lead to poor awareness of the need for greater services for the afflicted. Stigma and discrimination against patients and families prevent people from seeking mental health care (WHO, 2013a[108]). There is a global human rights emergency in mental health, and all over the world people with mental disabilities experience a wide range of human rights violations (WHO, 2013b[109]). These include physical restraint, seclusion and denial of basic needs and privacy. Few countries have a legal framework that adequately protects the rights of people with mental disorders (WHO, 2013c[110]).

And what about facilities?

There is overwhelming worldwide shortage of human resources for mental health, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries, which is well established (Kakuma et al., 2011[40]). As the WHO so succinctly puts it:

Globally, there is huge inequity in the distribution of skilled human resources for mental health. Shortages of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychologists and social workers are among the main barriers to providing treatment and care in low- and middle-income countries. Low-income countries have 0.05 psychiatrists and 0.42 nurses per 100 000 people. The rate of psychiatrists in high income countries is 170 times greater and for nurses is 70 times greater. (WHO 2013d[111])

Just consider this: in a population of 1.21 billion in India (GOI, 2011[31]), there is just 1 psychiatrist per 200,000 population, i.e., 0.5 psychiatrist per 100 000 population (Jebadurai, 2013[39]). Compare this with OECD* countries where, in 2011, there were 15.6 psychiatrists per 100 000 population on an average across OECD countries (OECD, 2013[69]), 31 times more than in India. [The number was by far the highest in Switzerland, with 45 psychiatrists per 100 000 population. Iceland, France and Sweden followed, with 22 psychiatrists per 100 000 population.] In most OECD countries, the number was between 10 and 20 per 100 000 population. There were fewer than 10 psychiatrists per 100 000 population in Mexico, Turkey, Chile, Korea and Poland. But even that is 20 times more than in India and such other developing countries.

In other words, we need 20 times the present number of psychiatrists in India if we want to even come near to doing some justice to mental health programmes.

What does that mean? At the least, existing centres need to double post graduate psychiatric seats, and an equal number of new centres need to be set up to come anywhere near 10 psychiatrists per 100 000 population in the next 10 years.

Stem the brain drain

In countries like India, we also need to stem the brain drain. There are more Indian origin psychiatrists in the USA than there are in the whole of India. If they were to have served this country, the number needed would have been 10 times, and not 20 times, more than what we have in India today. [That, of course, is wishful thinking.]

What we need to do to stem the brain drain is make psychiatry as a career more attractive and lucrative in this country. That is a topic in itself, but sustained stigma removal, greater attractiveness as a career option, and greater government spending over mental health can all act as the necessary spurs.

Prevalence of mental disorders

Again, taking the example of India, in a population of 1210 million (State Census 2011[99]), the prevalence of ‘serious mental disorders’ is 6.5% (Thirunavukarasu and Thirunavukarasu, 2010[101]), which is 78.6 million, i.e. nearly 80 million people, more than the population of states like Tamil Nadu (72 million), Madhya Pradesh (72.6 million), Rajasthan (68.6 million), Karnataka (61 million), Gujarat (60.4 million), Odisha (41.9 million) or the combined population of the northern top of India, including Punjab (27.7 million), Haryana (25.3 million), Jammu and Kashmir (12.5 million), Uttarakhand (10 million) and Himachal Pradesh (6.9 million), a total of nearly 82.4 million (State Census 2011[99]). And this is only a ‘serious’ mental disorders statistic. The population of those suffering from minor mental disorders is likely to be twice this.

Worldwide prevalence statistics show that at any given point, 10% of the adult population will report having some type of mental or behavioural disorder (WHO, 2001[106]). Which really means that, at any given point in time, every tenth person you meet is in likely in need of mental health care.

Need for serious activism

Such a huge population of people in India, and all over the world, suffers from mental disorders. And yet mental health care languishes at the bottom of health care delivery systems almost everywhere, with mental health being low on governmental health planning and spending.

If ever a greater role for activism were needed, this is the field.

There is sustained campaign for tackling communicable diseases, and for certain lifestyle diseases, which is justified, of course. But the colossal neglect of large-scale sustained activism in the field of mental health is criminal. There may be many reasons for this. But it is high time that mental health activists and workers started the ball rolling, and accepted no reasons to justify the present, or future, apathy.

Amongst the 5 key barriers to increasing mental health services availability WHO lists lack of public mental health leadership as one (WHO, 2013e[112]). The need is for sustained advocacy by diverse stakeholders, especially to target multilateral agencies, donors, and governments, and political will and solidarity, above all, from the global health community (Lancet Global Mental Health Group et al., 2007[47]).

We will do such sustained activism and advocacy only when we realize the vast task undone that lies ahead.

Many areas in developed world underserved

Also worth noting is that even in OECD, as in many other parts of the developed world, there are many areas still underserved. For example, in Australia, the number of psychiatrists per capita in 2009 was two times greater in certain states and territories compared with others (AIHW, 2012[3]). The disparity in urban and rural populations, in India, as in other such countries, is stark. Even in countries well covered there are vast populations waiting for NHS appointments. And, in countries like India, the huge queues that stand outside psychiatric OPDs in major municipal and government general hospitals is testimony to the fact that many more qualified mental health personnel are needed even in urban areas.

Scale up services and needed financial resources

The need, thus, is for policymakers all over the world to act on the available evidence to scale up effective and cost-effective treatments and preventive interventions for mental disorders (Patel et al., 2007[77]), with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries (Saraceno and Dua, 2009[84]; Lancet Global Mental Health Group et al., 2007[47]), but not restricted to them. The call to scale up mental health care is not only a public health and human rights priority, but also a development priority (Lund et al., 2011[55]). The grand challenge is to integrate mental health care into the non-communicable disease agenda (Ngo et al., 2013[65]), and into priority health care platforms (Patel et al, 2013[76]).

The redeeming fact is that financial resources needed to better and increase mental health services are relatively modest, US$ 2 per capita per year in low-income countries and US$ 3-4 in lower middle-income countries (WHO, 2013f[113]). It now only depends on the political will spurred on by an enlightened public aware of its needs and rights, wherein mental health workers take an active participatory, and more important, leadership role.

Wake up call

A lot of psychiatrists seem either unaware of all this, or are wrapped up in their cynical slumbers. Governments work only on sustained proddings, and have their priorities elsewhere. Psychiatrists, with some exceptions, make poor activists, or campaigners for causes, or lobbyists. So mass psychiatric care languishes with a few new token departments opened here or there. And the condition of state run mental hospitals is near the bottom in care excellence and credibility, with ‘institutions that resemble human warehouses rather than places of healing’ (WHO, 2013g[114]).

Mental health legislation: Lot done, lot to be done

In scaling up mental health services, progressive legislation plays an important part too. Let's take the example of India. Some notable changes in mental health legislation have happened in India in the last hundred years, from 1912 to 2011.

Mental health legislation has improved from the archaic ‘Indian Lunacy Act 1912’ to the relatively progressive ‘Indian Mental Health Act 1987’ (MHA, 1987), and further to the disabilities empowering ‘Persons with Disabilities Act 1995’ (PDA-95) and the ‘National Trust Act 1999’. Further, the December 2006 adoption of the ‘United Nations Convention for Rights of Persons with Disabilities-2006’ (UNCRPD-2006) was ratified by the Parliament of India in May, 2008. Amendment in MHA-87 was set in motion and a draft ‘Mental Health Care Bill — 2011’ (MHCB-2011) has been prepared. PDA-95 is also under revision and a draft, ‘The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2011’ (RPWD Bill-2011) has been submitted to the Indian Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MSJE) (Narayan and Shikha, 2013[63]).

While these are important steps forward, other progressive legislations, about suicide and homosexuality for example, languish in India for want of sustained campaigning by mental health workers, psychiatrists included. The general population's and affected communities’ activism would get a shot in the arm if psychiatrists, and other mental health workers become their supporters, even co-campaigners. Of course some work in this direction is being done, but more, much more, is needed.

Poverty, illiteracy and outmoded cultural beliefs triple bug-bears

Poverty, illiteracy and outmoded cultural beliefs are the triple bug-bears of efficient psychiatric services in all developing societies, India included. Part of the reason why psychiatric services are not so well spread is because awareness that it can help has not spread to uneducated populations, which still rely on magic and witchcraft to address mental health problems. And since we are not available, they have no option but to continue availing of such archaic services. Part of the reason why psychiatric disorders become chronic is also this. By the time they do land up with proper psychiatric services, it may often be years, and chronicity has set it. And even then, they may just land up in mental hospitals, to be incarcerated long term in some ward.

So it's a vicious cycle. We are not available, so services cannot be availed. Disorders become chronic by the time they are. So psychiatry fails to earn a good name since it can do little for such patients. And that which cannot earn a good name cannot be promoted in health care delivery systems. And we come full circle. We are not available, so cannot offer care. We cannot offer care, so we are not the priority in health planning.

The solution

So what do we do?

A sustained activism and pressure on policy planners to show how psychiatry works in those who come in our care; a sustained campaign to show how it is necessary to offer it to those who are exposed to witchcraft and black magic at present; sustained pressure by Regional and National associations, with help of reliable data, national and international, so that greater number of mental health delivery centres are set up in target areas for target populations. And not resting till India, and such other developing countries, come near par with the developed world in such facilities per unit population.

In Societies better off

Also, where societies are better off with regard to number of services, we need to increase the staff, so NHS appointments do not take that long, waiting in OPD queues is reduced, and greater number of inpatients can be admitted.

More psychiatrists must take up administrative and leadership roles in general hospitals with psychiatric care and see to it this gets implemented. There is no need to be coy or discreet about his. That one is a clear-cut proponent and will not rest till facilities improve must be clear to colleagues and authorities. If there is opposition, so be it. Nothing succeeded till one wins over, or trounces, such opposition. Petitions and pleading do work, but only up to a point. Even Gandhiji realized this in his campaign to root out the British rule. He replaced petitions and pleadings with use of activist tools like Non-violence and Peaceful Non-cooperation. Only here our tools are scientifically validated information about how psychiatry works, how it is needed in areas where it's not available, and how it needs to be strengthened in areas where it already is present.

There is an ‘independence movement from mental ill health’ waiting to be carried out in India, and such other countries, where mental health care still languishes.

Study how activism works

A study of how activism works, a study of the history of psychiatry and what the past masters had to struggle through to reach us where we are, and a sustained effort to reach untapped areas and increase facilities in already tapped areas is the need of the hour. The WHO's 2008 Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) (WHO, 2008[107]), which advocates a greater focus on mental health in global health policies, is a must read for those who plan such advocacy and activism.

Association leaders, psychiatric activists, and those with a fire in the belly to do something good, regardless of the opposition — in fact, those who enjoy handling such opposition and trumping it — this appeal goes directly to them.

Combating imbalance between burden of demand and supply of efficient psychiatric services

Combating this imbalance between the burden of demand and the supply of efficient psychiatric services in all countries, and especially in the developing ones like India, is the first task before psychiatry today.

The Second Task: Speak to a Wider Audience About Positive Contributions of Psychiatry, i.e., Talk

Just do a Google/Yahoo/MSN search on ‘Psychiatry’, ‘Positive Aspects of Psychiatry’, ‘Anti-Psychiatry’. You will get a lot of matter to browse. Please do. It will be an eye-opener.

While you will get to read matter on positive contributions of the branch, quite a lot of it would be about negative aspects of psychiatry: How it is useless and dangerous; how it harms and is an infringement on human rights, free will etc; how barbaric is ECT treatment; how dangerous are its medications etc. It goes on and on and on. And while you and I sit in our consulting rooms and our OPDs, and our seminars and conferences and committees and task forces, debating this and that issue and ostensibly working for patient welfare and therapeutic advancement in psychiatry, a major part of the world around remains unimpressed and keeps ranting about the ill-effects of our branch.

Psychiatry and its critics

There is something about psychiatry that attracts the most vehement protests. No other branch of medicine sees such vilification heaped on it.

And yet, those who are in the system know they are doing the best thing possible for their patients/clients. And it is the one system that is most open to discussing what needs to be improved about it. While many other systems of medicine would dismiss most protests with a shrug, psychiatry is one branch that considers ethical, conceptual and foundational issues, sometimes almost to the point of becoming paralysed for action due to this.

Every psychiatrist knows the benefits of ECT in selected patients. Every psychiatrist knows how psychopharmacology has revolutionised patient care. The grateful patients who have been saved from suicide, who get rid of their delusions/anxieties/phobias/depressions to lead a productive life, whose inter-personal and intra-personal problems have been resolved with psychotherapy — all these are so very well known in psychiatric practice. And yet the vilification of the branch continues.

Of course not all of anti-psychiatry has been useless and only vitriol. One can understand the contributions it has made to mental health consumerism. (Rissmiller and Rissmiller, 2006[80]; Ostrow and Adams, 2012[71]; Torrey, 2011[102]). And it has added enlighteningly provocative critiques to ‘establishment’ psychiatry in the form of thinkers like Michel Foucault in France, R. D. Laing in Great Britain, Thomas Szasz in the United States and Franco Basaglia in Italy (Rissmiller and Rissmiller, 2006[80]). It essentially champions personal liberty and freedom, and that is a laudable approach. But it also opposes any attempt at a definition of normalcy that, according to it, the establishment of psychiatry tries to ‘impose’ on nonconformists and society at large. Here it transgresses its legitimate domain, for a definition of normalcy is essential, although difficult, as is a definition of the abnormal. And every non-conformism is not legitimate. That which confronts social prejudices and stereotypy, is; but that which tries to delegitimize people's disease and resultant distress, suffering and anguish in the name of non-conformity, isn’t. What we label as psychiatric disorders falls in the latter category. Psychiatric disorders may involve non-conformity, but thinking of them as only non-conformity, and brushing aside the distress and anguish it causes to sufferers and their caregivers is one form of care deprivation. Also, one can question the medicalisation of problems of living, whose greatest manifestation is in psychiatry (Maturo, 2013[56]), but one cannot brush aside those stable symptom clusters that go on to get categorised as a new psychiatric disorder.

Moreover, the inability to precisely define a certain phenomena, as for example the difference between normal and abnormal (see, for example, Mayo Clinic 2013a[57], for such a distinction), does not mean it does not exist. It only requires a more clear-cut delineation, which researchers need to work over that much the more diligently. Studies on normality need greater emphasis than is their lot at present.

While every attempt must be made to engage energies in such definition, it is more necessary to move on and outline the processes and manifestations of abnormality in the different forms that it takes, and find appropriate methods of treatment and care.

In other words, major energies must be concentrated on the aetio-pathology, diagnostic finesse and treatment of the myriad psychiatric disorders, and define and treat them with greater and greater precision (Singh, 2013[94]).

Patients who get well

The whole problem also is patients who get well do not talk. They go on with leading their lives and often want to hide their psychiatric history for fear of stigma.

It's a rare instance that a man would speak as eloquently about his psychosis and how he got rid of it, as he would about his recent bypass, or appendectomy, or whatever. [Some notable exceptions are Frese, 1993[23]; Kate, 2013[44]].

It's not that treatment failures do not occur in other branches of medicine. But they are accepted as part of the process. No one wants them. But no one dies a thousand deaths over them. However, in psychiatry, its opponents trumpet every treatment failure so loud as to scare so many more who would greatly benefit by it.

Mercifully, the anger and vituperative outbursts of some of the earlier critics of psychiatry seem to show signs of abating. They have, in a way, found ways to sublimate their anger and aggression. As noted earlier, it is encouraging to note that most anti-psychiatry today is not as keen to focus on dismantling organized psychiatry as on seeking to promote radical consumerist reform (Rissmiller and Rissmiller, 2006[80]). Good for them and good for us too.

However, a substantial section of the disgruntled, which possibly also includes those incompletely treated, continue to relentlessly pour acid comments on the branch.

The easiest option and what do we do

What do we do? The easiest option is to do nothing about it. And that's what most of us probably do. Or go on doing one's bit to the best of one's ability. And think of the grateful faces of those helped. And wait for saner counsel to prevail in the less charitably disposed.

That's a good ploy to keep one's equilibrium in the face of acerbic comments. But it's hardly likely to counter their thrust. And it's hardly likely to help motivate those who can be helped by psychiatric therapy to seek it. In fact, negative comments about the branch, or its practitioners, have the uncanny ability to dissuade the needy from seeking help, even if they continue to suffer because of such a refusal.

The remedy for this is not just remaining quiet and doing one's work, but rather is asking oneself this simple question: If every psychiatrist knows the benefits his patients get by his treatment, what does he do to let the world around know that his methods work?

I would, therefore, urge you to give up on your slumbers and make some effort to list the positive contributions of our branch in general, and your own in particular, to make life worthwhile for the psychiatric patient.

It's not just enough to be convinced yourself about the worth of your branch. That is important, but not enough. It's also important the tirade against psychiatry is fittingly countered, by clear cut therapeutic evidence, by patient data, by statistical details, by replicated studies.

Speak up, patients and clinicians

Maybe it is also time for those who have been helped by psychiatry to speak up.

Patients who get well are grateful, but often just remain anonymous. Stigma (for various facets of stigma discussed at MSM, see Reeder and Pryor, 2008[79]; Shrivastava, Johnston, Bureau, 2012a[90], 2012b[91]) and its fear makes them become just part of a statistic, in a clinic, or hospital, or research paper. They are apprehensive about speaking out aloud about the benefits of treatment. The disgruntled elements have no such compunctions. So they jolly well shout from roof-tops. And the e-world is inundated with their vitriol.

It's time you and I did something to mend matters.

Pick up your pen. Write about how psychiatry helps. If possible, put up a web site, alone or in a group, where authentic information and guidance about psychiatry is available; and especially highlight what are its positive contributions. Not propagandist, not evangelical, just the facts. (See, for example, MedLinePlus 2013[61], APA 2013[6], RCPsych 2013[78], NIH 2013[66]; Mayo Clinic 2013b[58], IPS 2013[38]; BPS 2013[9]. This is just a representative sample.)

Let patients and patient groups, who are benefited, speak. Let those who are not afraid to come out of the closet and have the necessary ability to communicate get a platform to talk how psychiatry has helped them. Let others who are helped but are diffident about coming out in the open find other avenues (anonymous) to voice their opinion.

A regular column in psychiatry journals around the globe, called ‘Patients Speak’ or something similar (see, for example, Needle, 2014[64]; Anonymous, 2007[5]), wherein those who have been helped get a chance to voice their stories, would be a step in the right direction. Occasionally, they may also voice their concerns, difficulties and criticisms, but only occasionally and never as a means to emasculate the branch, or deride fellow practitioners.

This is the second task before psychiatry and psychiatrists today (see also Garg and Garg, 2014[28], elsewhere in this issue).

The Third Task: Shrug Ambivalence and Disagreement; Search Commonalities in Psychiatric Phenomena i.e. Science

Reconciling the nomothetic-idiographic dichotomy

There is a lot of ambivalence about the contributions of psychiatry in the minds of psychiatrists themselves. There is more disparity in thought and approach about almost every psychiatric disorder and therapy than there are drops in the Indian Ocean.

Psychiatrists seem to thrive on disagreement. They stress individuality almost to the point of denying any commonality and scientific categorization. While it is true that each patient is unique and requires individual handling, he is also part of the human race, which has many things in common.

Reconciling the nomothetic-idiographic dichotomy, the IGDA mentions:

The diagnosis itself should combine a nomothetic or standardised diagnostic formulation (e.g. ICD-10, DSM IV) with an idiographic (personalised) diagnostic formulation, reflecting the uniqueness of the patient's personal experience’. [IGDA WORKGROUP, WPA. IGDA, 2003a[36]; IGDA WORKGROUP, WPA. IGDA, 2003b[37].

However, an idiographic orientation which stresses individuality cannot, and should not, preclude the nomothetic or norm laying thrust that is the crux of scientific progress. The major contribution of science has been to recognize such commonalities so they can be researched, categorized and used for human welfare (See also Singh, 2014[95], in this issue). There can be a well-intentioned, but misplaced, rejection of the reductionist approach (Nys and Nys, 2006[68]). It would help in this connection if the autonomy disease model in psychiatry would be carefully debated (Schramme, 2013[88]), but that is obiter dicta here.

Lay intelligent observer, scientist, individuality and commonality

What is the difference between a lay intelligent observer and a scientist?

A lay intelligent observer would try to find out the individual variations and peculiarities of abnormal behaviour as it manifests in different individuals and different cultures. A scientist will try to decipher the commonalities in the abnormal behaviour across cultures and peoples so he can find stable symptom clusters that can be labelled as diseases/syndromes etc. Which then help him decide a plan of therapy and delineate the course and outcome of the said disease/syndrome.

What do we mean thereby? While a lay intelligent observer will stress mainly on the different ways schizophrenia manifests in different cultures and demographic areas even if they may have some common features, the scientist will stress mainly on those common factors that make it schizophrenia even though it may manifest differently in different cultures and demographies.

It is a mistake to stress individuality so much that commonalities are obliterated, for that is counter-scientific. Well-meaning psychiatrists will have to be especially careful they do not carry their honestly intentioned emphasis on individuality to ridiculous limits. This is what makes some of them come dangerously close to being unscientific themselves and makes a few, if not most of them, consort with willing accomplices from the anti-psychiatry group.

In fact, most of those in the other group are basically anti-science, as applied to psychiatry. This means they somehow consider the scientific method as unsuited and inadequate for the psychiatric approach. That is their fundamental peeve.

A conceptually flawed position

It's a conceptually flawed position, precisely because psychiatry is a branch of care where patients, therapy and sickness is involved. And while holistic understanding is necessary to study intimate nuances of psychological/psychopathological processes and while individual manifestations and individual approach are laudable goals in treatment and approach, we cannot forget that major therapeutic advances result from being able to delineate commonalities and stable symptom clusters that are amenable to study and intervention.

In other words, signs/symptoms, diagnosis, diagnostic manuals, clinical practice guidelines, standardized treatments.

Let us appreciate the fact that although stress on the individual's needs has helped psychiatry at times become more humane, it has hurt the task enormously by making some very bright minds question the very scientific basis of psychiatry. There can be no doubt on the issue that while the purpose and approach of psychiatry, as of all medicine, has to be humane and caring, the therapeutic advancements and aetiologic understandings are going to result only from a scientific methodology.

The art is in the caring approach,: the touch, the tone, the outlook. The total attitude of the care-giver and the way that care is administered. Here all medicine, psychiatry included, is an art. But it is a science in the methods used, both in therapy and diagnosis.

Let both these complement each other, but not blur boundaries. The art cannot become the approach itself. Just caring is not enough, if you have not mastered the methods of care, which only science can supply to medicine in general and psychiatry in particular (since we are concerned with it here).

This message must go clear into our minds.

Reemphasis on science, without of course excluding the art, is the third task before psychiatry today.

The Fourth Task: Psychiatrists Must Continue to do Psychotherapy i.e. Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy as a therapeutic tool

The psychotherapeutic approach holds tremendous potential as a therapeutic tool in psychiatry. But it is a myriad bunch of therapies, sometimes so diverse and so disparate that it arouses doubt whether it is scientific after all. At times it seems to be a free for all. This state of affairs needs to be speedily remedied.

Psychotherapy must be clearly defined, its parameters and methods firmly delineated, its proof of effectiveness convincingly demonstrated by evidence based and controlled trials. Here are some important efforts in this direction: studying the effectiveness of long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy by meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (Smit et al., 2012[92]); review of recent process and outcome studies in short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (Lewis, Dennerstein and Gibbs, 2008[54]); empirically supported treatments in psychotherapy leading towards an evidence-based, or evidence-biased, psychology in clinical settings (Castelnuovo, 2010[11]); evidence-based medicine in psychotherapy (Henningsen and Rudolf, 2000[34], article in German). Also, worth noting is the sustained work, over the last decade [2004-2013] by Leichsenring and colleagues on various aspects of evidence-based practice of short-term and long-term psychotherapy: See, for example, 1) psychotherapy and evidence-based medicine (Leichsenring and Rüger, 2004[53], article in German); 2) meta-analysis of the efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific psychiatric disorders (Leichsenring, Rabung and Leibing, 2004[52]); whether 3) psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies are effective at all (Leichsenring, 2005[48]); following up with a, 4) meta-analysis of the effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (Leichsenring and Rabung, 2008[50]); and 5) its update (Leichsenring and Rabung, 2011[51]); and 6) the recent paper showing the emerging evidence for long-term psychodynamic therapy (Leichsenring et al., 2013[49]). It is sustained work such as these that will reestablish psychotherapy to the preeminent position it so richly deserves.

Psychotherapy suffers from neglect and resource constraints

We know psychotherapy suffers from not a little neglect by the mainstream at present, with some predicting the impending and perhaps inevitable collapse of psychodynamic psychotherapy as performed by psychiatrists (Drell, 2007[19]); and many who are concerned with its training and revival, in Canada (Chaimowitz, 2011[12]); in the UK, Australia and New Zealand (Rodrigo et al., 2013[83]); in the UK and globally (Holmes, Mizen and Jacobs, 2007[35]); and in the USA (Mojtabai and Olfson, 2008[62]).

We also know it suffers from a major resource constraint at present. That's because an important funding source, like the pharmaceutical or the medical device industry, is hardly likely to further genuine research in psychotherapy. And we know that's simply because it would be counterproductive to their very existence, based as they are on furthering the biological approach. But that is all the more reason some sincere researchers and altruistic sponsors, as also professional societies and governments themselves, become catalysts in this direction. It is important to search out such, and it is important that professional societies, flush as they are with funds they often don’t know what good to do with, take up such worthy causes. For example, the Indian Psychiatric Society has handsome funds lying in its kitty, which it keeps multiplying in fixed deposits. Nothing wrong with that. But it is high time part of such funds were mobilized to further research fellowships in neglected areas of research, like psychotherapy and social psychiatry. Some salvaging of pride and retribution of guilt for the massive pharma funding that makes for Association funds. And what is applicable here is equally applicable for other professional societies with funds. What use money if not put to proper use?

What proponents of psychotherapy must do

Equally importantly, proponents of psychotherapy will have to give up on their cynical disregard for the positive contributions of the biological approach. They will also have to forsake their archaic methods to prove effectiveness and stop being impressionistic and subjective, or sit in their cocoons idolizing their approach. They will have to provide enough irrefutable evidence that their methods work. And enough replicable studies that prove it across geographical areas.

The time to sing platitudes for the psychotherapeutic approach, or lament its neglect in circles of contemporary influence, is past. Only solid evidential basis will sustain it, or any other branch, in the future. As Singh and Singh, 2004-5[96] mention:

Ultimately, the psychotherapeutic approach itself will benefit by shedding its smug somnolence, become more evidence and experiment based, offer verifiable population statistics to back up its contentions and compete with biological approaches with greater methodological rigour. (Singh and Singh, 2004-5[96])

Anyone who is only a psychopharmacologist is only half a psychiatrist. But anyone who is only a psychotherapist is equally only half a psychiatrist. The total picture is painted only when both approaches are judiciously merged in the training and application of the individual psychiatrist, and his branch itself.

Let's not get carried away by the sloganeering on either side. Let the committed proponent of either branch not find any virtue in such of his commitment as makes him oblivious to the strengths of his opponent and shortcomings of his preferred approach. In fact, his commitment should, if at all, make him acutely aware of the shortcomings of his preferred approach and make him equally acutely aware of the merits of his opponents’. (Singh and Singh, 2004-5[96])

Handing over psychotherapy to clinical psychologists

Also, it will not do for psychiatrists to hand over psychotherapy to clinical psychologists and others. Psychiatrists may enjoy priding themselves in becoming doctors in the sense they are commonly understood, when they mainly prescribe drugs and carry out ‘medical’ procedures and interventions. Psychiatrists feel justifiably proud in prescribing drugs and giving ECTs. They would not want to hand over these responsibilities to others, would they, for they consider them their legitimate areas of expertise? Then why do they find it justified handing over doing psychotherapy to others? If lack of time is the justification, will they say the same when it comes to drug prescribing and ECTs? Will they hand over ECT treatment to trained technicians, or drug treatment to trained pharmacologists, just because they don't have the time? Let's stop kidding ourselves.

The fact of the matter is psychotherapy is time consuming, taxing on the mental resources of the therapist and doesn't offer clear-cut tangible rewards. Moreover, it's not fashionable to be considered a psychotherapist, while it is an ego-booster to say that one has a couple or more of trained clinical psychologists in one's team to handle ‘psycho-social’ issues. That may do good to the psychiatrist's self-esteem, but it does hardly any good to his credibility and standing as one.

In sum, then, it makes eminent sense for psychiatrists to continue to do psychotherapy. And it makes equally good sense for them to encourage/demand for well-designed studies that compare and contrast the different forms of psychotherapies and offer clear-cut guidelines of effectiveness and approach.

The Fifth Task: Welcome Biological Breakthrough, Supply Psychosocial Insights i.e., Integrate approaches

There is a huge mass of research outpouring in biological psychiatry, and not without reason. The quest to find biochemical and neurophysiological underpinnings of mental phenomena in health and disease is a legitimate exercise and likely to yield fruitful results for aetiopathologial and therapeutic advance. The biological approach in psychiatry holds great promise to someday unravel the intricacies and mysteries of the brain in health and disease, a promise no other approach holds as much (Singh, 2013[94]).

Breakthroughs from biology, insights from the psychosocial and philosophical

What then is the role of psychosocial approaches to psychiatric disorder? Are they redundant?

While the experimental breakthroughs, both in aetiology and therapeutics, will come mainly from biology, the insights and leads can hopefully come from many other fields, especially the psychosocial and philosophical. It is in some such synergy that these two supposedly antagonistic branches must engage themselves, to complement and nurture rather than confront and dismember.

Call for, and attempts at, integration

Nobel Laureate Kandel's dream of the integration of cognitive neurosciences with scientific psychoanalysis, (Kandel, 1998[41]) and the wish that psychoanalysis reenergize itself by developing a closer relationship with biology in general and cognitive neuroscience in particular (Kandel, 1999[42]); as also the plea for the synthesis of cognitive psychology and neuroscience (Singh and Singh, 2004-5[96]) are attempts to combine the insights of the psychoanalytical/psychosocial/philosophical with breakthroughs from the biological. Moreover, the promise that Neuroscience holds as it breaks down barriers to the scientific study of brain and mind, (Kandel, 2000[43]), is worth a close look as it offers means to provide such synergy too. The sustained work to delineate the neurobiology of mental disorders (for useful overviews, see, for example, Charney and Nestler, 2011[14]; Mohandas, Avasthi and Venkatsubramanian, 2010[61]), as of individual mental disorders (for example, of major depressive disorder recently, Villanueva, 2013[105]), are also worthy attempts at providing breakthroughs through the biological approach, even if we do accept there are no known biological markers in psychiatry at present (Turck, 2009[103]; and that condition still continues in 2014).

The many recent approaches at integration of approaches in psychiatry and interdisciplinary work and approach are worth a close look. Especially noteworthy are the following: combining neuroplasticity, psychosocial genomics, and the biopsychosocial paradigm in the 21st century (Garland and Howard, 2009[29]); understanding mental health clinicians’ beliefs about the biological, psychological, and environmental bases of mental disorders (Ahn, Proctor and Flanagan, 2009[2]); essentials of psychoanalytic process and change and how we could investigate the neural effects of psychodynamic psychotherapy in individualized neuro-imaging (Boeker et al., 2013[8]); the clinical case study of psychoanalytic psychotherapy monitored with functional neuroimaging (Buchheim et al., 2013[10]); operationalized psychodynamic diagnosis as an instrument to transfer psychodynamic constructs into neuroscience (Kessler, Stasch and Cierpka, 2013[45]); collaboration between psychoanalysis and neuroscience historically (Sauvagnat, Wiss and Clįment, 2010[85]); psychoanalytic self psychology and its conceptual development in light of developmental psychology, attachment theory, and neuroscience (Hartmann, 2009[33]); relational trauma and the developing right brain: an interface of psychoanalytic self psychology and neuroscience (Schore, 2009[87]); grounding clinical and cognitive scientists in an interdisciplinary discussion (Ottoboni, 2013[72]); mind/body debate in the neurosciences (Dolan, 2007[18]); mind, brain and psychotherapy (Sheth, 2009[89]); psychoanalysis and the brain (Northoff, 2012[67]); linking neuroscience and psychoanalysis from a developmental perspective (Ouss-Ryngaert and Golse, 2010[73]), and dialogue between psychoanalysis and social cognitive neuroscience (Georgieff, 2011[30]), with psychoanalysis on the couch and neuroscience providing answers (Mechelli, 2010[59]).

Some esoteric topics worth a look

It would also help for psychiatrists who seek a deeper interdisciplinary understanding to focus a bit of the mind-body problem as philosophers understand it: on the development of the concept of mind itself (Bennett, 2007[7]); of soul, mind, brain and neuroscience (Crivellato and Ribatti, 2007[16]). For the more adventurous, there are some rather difficult topics like the philosophy of/and psychiatry (Fulford et al., 2007[25]; Singh and Singh, 2009[97]). And for the further curious, there are some catchy ones like ‘Pharmacotherapy for the soul and psychotherapy for the body’ (Groleger, 2007[32]); philosophical “mind-body problem” and its relevance for the relationship between psychiatry and the neurosciences (Van Oudenhove and Cuypers, 2010[104]); and even topics like embodiment and psychopathology from a phenomenological perspective (Fuchs and Schlimme, 2009[24]). Some reflection would also be fruitful on the connection between brain and mind in formulations like ‘Brain is the structural correlate of the mind, as mind is the functional correlate of the brain’ (see Brain-Mind Dyad, Singh and Singh, 2011[98]).

Integration is necessary

Integration of approaches is essential for a complete psychiatrist (See also Gabbard, 1994[26]). He has no option, really. The biological and the psychological are not exclusive but complementary approaches (Singh and Singh, 2004-5[96]). There can be no changes in behaviour that are not reflected in the nervous system and no persistent changes in the nervous system that are not reflected in structural changes on some level of resolution (Kandel, 1998[41]).

An insightful comment, which sums up what is the essence of the integrative approach for the psychiatrist, is the one by Gabbard:

Just as the physicist must simultaneously think in terms of particles and waves, the psychiatrist must speak of motives, wishes and meanings in the same breath as genes, neurochemistry and pharmacokinetics. Gabbard, 1999[27]

Integration and reductionism: Both valid

If integration is valid, how does reductionism fit in?

Although integration of approaches is necessary, the reductionist approach of biology is eminently suited to aetiologic understandings as well as therapeutic breakthroughs. Often, too many approaches result in a multitude of viewpoints that obscure and mystify rather than simplify and clarify phenomena. The aetiology and definitive therapy of major conditions in psychiatry would have been known earlier if we were not bombarded by a plethora of conceptual formulations that, in the name of justifying how complex and mysterious the mind is, only obfuscate issues and make the terrain so much more difficult to tread. If the scientific approach is robustly furthered and the reductionist/replicable approach firmly adhered to, significant insights into aetiology and therapy of major psychiatric conditions will yield themselves to the keen researchers’ probings.

Hence, although integration is necessary as an attitude, reductionism is necessary as an approach. Both must co-exist in the individual psychiatrist, as much as the branch itself.

Such integration is the fifth task before psychiatry today (see also Tekkalaki, Tripathi and Trivedi, 2014[100], elsewhere in this issue).

The Sixth Task: Promote Genuine Research Alone and Work Towards an Indian Nobel Laureate by 2020 i.e., Research Excellence

Change mindset: Get rid of awe and subservience to the western mind

A lot of research in psychiatry is substandard, especially in India. While we may probe the reasons why it is so, the major cause is a mind-set that does not allow for a conviction that anything trend setting can result from here. This scenario will hopefully change in the next few years as the Indian has now developed a new-found confidence in his own abilities and, over the next decade or two, will get rid of his awe and subservience to the western mind. The changed economic and socio-political climate, with the manner in which Indian enterprise is making its mark on the world scene in most walks of life, as also the fact that Indians are no longer treated with outright contempt or disguised condescension abroad, something that was their lot till very recently — all these have made for a firm current of positive self-esteem in the Indian of today.

It will not take long for this current to become a torrent in the next decade. And it should not take long for this heightened self-esteem to percolate to the scientific and research fields too. Indian medicine and psychiatry should be its major beneficiaries.

The task for Psychiatry departments and research units in India: Promote research excellence alone

The task before major departments and research units in psychiatry all over the country is to respond to this change with vigour and conviction. The need is to stop engaging in poor quality research. The need is to stop waiting for the next important discovery to come from the West. The need is to believe in oneself and become the next Center from where important breakthroughs can result.

For that it is necessary for heads of units to tighten their belts: to stop promoting poor quality research, and researchers; to stop encouraging sycophants and ladder climbers; and to pick up and hone genuine research talent from amongst their faculty and students. Let us not rue the fact that promising talent seeks to run to the West for brighter pastures there. This is inevitable for some more time. But if we offer them comparable research facilities and a clean work environment that encourages and hones talent — and with the changed economic and political scenario that has unshackled the economy and promotes individual growth — it is very much possible more and more genuinely talented researchers and clinicians would want to stay. The important thing is for Heads of Units, and policy makers and decision takers, not to get cynical and give up on promoting excellence in their respective work places because some promising talent drains away.

If we are persistent enough and offer quality setups, the time when talent will come back seeking work here is also not far away. And the brain drain will get stemmed as well. But all this will not happen by itself. There is no Santa who will offer it as a gift. It will only result by developing consistent quality environs in the departments and having Heads of Units who recognize, hone and nurture talent. And who never give in to pessimism and cynicism.

An Indian Nobel laureate in Psychiatry by 2020

I am no soothsayer, but there is no doubt in my mind that there will be a Nobel Laureate in medicine/physiology of medicine from India in the next few years, 2020 or thereabouts. We have to decide if this Nobel Laureate will be from the field of psychiatry.

It is not that difficult a task. But it will only happen if a number of psychiatric departments all over the country are engaged in quality research for the next few years.

Which department will produce the Nobel Laureate we may leave to destiny. But it will result only when most departments believe it is within the realm of possibility and put in earnest efforts to become the chosen one (some useful resources on how to win a Nobel prize are Agre, 2012[1]; CNN[15]; Doherty, 2006[17]; English 2013[21]).

When a stable wants to produce champion thoroughbreds, it does not bank on a single horse. It identifies a number of potential champions, hones and nurtures them, with care and caution, and waits for one, or more, from the brightest to win the race for them.

Similarly, a number of psychiatric research departments and research institutes will have to engage in top quality research for a couple of decades for some champion from amongst the many thoroughbreds so produced to win the race for them.

If you are one who heads such a department, you know the task that is cut out for you. If you are one who has such a winner in sight, or as a member of your department, you know what you have to do. And if you are one who believes you can be one such potential winner, you know the terrain you must traverse.

Just stop doing, and promoting, poor quality research work. Just stop the temptation to earn a quick buck by doing the next drug trial. Just stop being satisfied with the money, power and prestige that comes by wheeling-dealing, groupism and politicking; and stop wasting energies in Association politics. Association work is fine, and necessary and laudable, but that too within limits, if doing quality research is your objective. Association politics, however, is to be firmly avoided, simply because it will drain you, emotionally and intellectually; and render you incapable of visualizing that anything higher than an official position is ever possible. You have greater goals to achieve and nobler tasks to perform. And they are within your grasp if you just reach out hard enough and persistently enough.

In closing

We entered the branch of psychiatry with a hope and desire to make a difference in the lives of our patients and work to fathom the mysteries of the mind. As Nancy Andreasen (2001[4]) asks: Why did we become psychiatrists and not cardiologists, radiologists, pathologists and surgeons? It's because we were interested in understanding what makes human beings tick in health and disease:

Every person whom we encounter is a new adventure, a new voyage of discovery, a new life story, a new person… We are privileged to explore the most private and personal aspects of people's lives and to try to help them become healthier. (Andreasen, 2001[4])

Somewhere down the line, however, most of us got bogged down with the nitty-gritty of living and ‘achieving’ and laurels and power and prestige. The glorious vision that made us take up the branch got blurred under the foliage of false leads and superfluous achievements. And a crippling cynicism that hurts any worthwhile foray into genuine research, or appreciating someone else who is so engaged.

Let's clear the dust from the picture. The radiance is still there. The magic can be recaptured, to guide and illumine the path to brilliance. Infinite vistas of opportunity wait in the wings to unfold and offer opportunities for unravelling the mysteries of the ‘mind’ to the earnest seeker. Provided he is ready to seek the valuable. Provided he stops holding on to the artificial and the superfluous. Provided he believes he deserves the very best and will not compromise on anything lesser, come what may.

It's a big game, my friends. Learn to play it big. The smaller fishes and loaves, of office and career and position and lucre, will pale into insignificance when you realize what larger issues beckon you to put your shoulder to the wheel.

Are you ready?

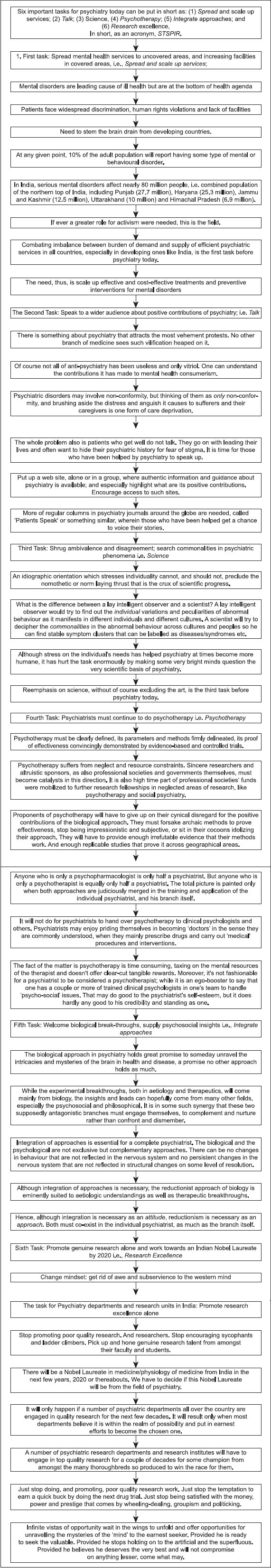

Concluding Remarks [See also Figure 1. Flowchart of paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the paper

Six important tasks for psychiatry today can be put in short as:

Spread and scale up services;

Talk;

Science,

Psychotherapy;

Integrate approaches; and

Research excellence,

In short, as an acronym, STSPIR.

Spreading mental health services to uncovered areas, and increasing facilities in covered areas i.e. Spread and scale up services: Mental disorders are leading cause of ill health but are at the bottom of health agenda; patients face widespread discrimination, human rights violations and lack of facilities; at any given point, 10% of the adult population report having some mental or behavioural disorder; the need is to scale up effective and cost-effective treatments and preventive interventions for mental disorders. Combating imbalance between burden of demand and supply of efficient psychiatric services in all countries, especially in developing ones like India, is the first task before psychiatry today.

Speaking to a wider audience about positive contributions of psychiatry, i.e., Talk: Being aware of, and countering, the massive anti-psychiatry propaganda online and elsewhere; giving a firm answer to anti-psychiatry even while understanding its transformation into mental health consumerism and opposition to reckless medicalisation; motivating those helped by psychiatry to speak up; setting up informative websites and organising programmes to reduce stigma and spread mental health awareness; h) setting up regular columns in psychiatry journals around the globe, called ‘Patients Speak’, or something similar.

Shrugging ambivalence and disagreement and searching for commonalities in psychiatric phenomena, i.e., Science: Idiographic orientation which stresses individuality cannot, and should not, preclude the nomothetic or norm laying thrust that is the crux of scientific progress; the major contribution of science has been to recognize commonalities so they can be researched, categorized and used for human welfare; while the purpose and approach of psychiatry, as of all medicine, has to be humane and caring, therapeutic advancements and aetiologic understandings are going to result only from a scientific methodology.

Psychiatrists continuing to do psychotherapy, i.e., Psychotherapy: Must be clearly defined, its parameters and methods firmly delineated, its proof of effectiveness convincingly demonstrated by evidence based and controlled trials; psychotherapy research suffers from neglect by the mainstream at present, because of the ascendancy of biological psychiatry; c) it suffers resource constraints as major sponsors like pharma not interested; d) needs funding from some sincere researcher organisations and altruistic sponsors, as also professional societies and governments; it will not do for psychiatrists to hand over psychotherapy to clinical psychologists and others.

Welcoming biological breakthroughs, while supplying psychosocial insights, i.e., Integrate approaches: Experimental breakthroughs, both in aetiology and therapeutics, will come mainly from biology, but insights and leads can hopefully come from many other fields, especially the psychosocial and philosophical; the biological and the psychological are not exclusive but complementary approaches; both integration and reductionism are valid: Integration is necessary as an attitude, reductionism is necessary as an approach.

Promoting genuine research alone, and working towards an Indian Nobel Laureate in psychiatry by 2020, i.e., Research excellence: Stop promoting poor quality research, and researchers, and stop encouraging sycophants and ladder climbers; pick up and hone genuine research talent from amongst faculty and students; develop consistent quality environs in departments and have Heads of Units who recognize, hone and nurture talent. c) Stop being satisfied with the money, power and prestige that comes by wheeling-dealing, groupism and politicking.

Take home message

The following are the six tasks before psychiatrists and psychiatry today:

Spread mental health services to uncovered areas, and increase facilities in covered areas, i.e., Spread and scale up services;

Speak to a wider audience about positive contributions of psychiatry, i.e., Talk;

Shrug ambivalence and disagreement and search for commonalities in psychiatric phenomena, i.e., Science;

Psychiatrists must continue to do psychotherapy, i.e., Psychotherapy;

Welcome biological breakthroughs, while supplying psychosocial insights, i.e., Integrate approaches;

Promote genuine research alone, and working towards an Indian Nobel Laureate in psychiatry by 2020, i.e., Research excellence.

In short:

Spread/scale up services;

Talk;

Science,

Psychotherapy;

Integrate approaches; and

Research excellence.

As an acronym, STSPIR.

Questions that this Paper Raises

How much, and what kind, of soul searching is enough, and healthy, for the branch?

What methods of scaling up mental health services are likely to work?

What stigma removal methods are practically useful?

How do we motivate patients and care givers to speak openly about the benefits of the branch?

How do we best combine the biological and the psychosocial approaches?

How do we promote the science in psychiatry without losing out on its art?

How do we get psychiatrists to do psychotherapy, and not just pass the buck to other mental health workers?

What concrete steps will ensure the next Nobel Laureate in psychiatry, as also an Indian Nobel Laureate in psychiatry by 2020?

About the Author

Ajai R. Singh, MD, is a Psychiatrist and Editor, Mens Sana Monographs (http://www.msmonographs.org). He has written extensively on issues related to psychiatry, philosophy, bioethical issues, medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. ©MSM.

Declaration and Acknowledgement

This is my original work, earlier version published as an article: Singh AR. The task before psychiatry today. Indian J Psychiatry 2007;49:60-5. Reproduced with thanks and permission of the Indian Jr of Psychiatry, and its editor, Dr T.S.S. Rao.

Edited and modified to conform to MSM guidelines and substantially updated to include some work since published, including in this issue.

Footnotes

OECD stands for Organisation for Economic cooperation and Development: An umbrella of countries from all over the globe; see OECD, Members and Partners, 2013[70])

Conflict of interest: None declared.

CITATION: Singh AR. The Task before Psychiatry Today Redux: STSPIR. Mens Sana Monogr 2014;12:35-70.

Peer Reviewers for this paper: Anon

References

- 1.Agre P. How to win a nobel prize? [Last cited in 2012 Jan 12, Last accessed on 2013 Dec 30];PLoS Biol. 2006 4:10. Available from: http://www.plosbiology.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pbio.0040333 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn WK, Proctor CC, Flanagan EH. Mental health clinicians’ beliefs about the biological, psychological, and environmental bases of mental disorders. Cogn Sci. 2009;33:147–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canberra: AIHW; 2012. AIHW, Mental Health Services in Brief 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreasen NC. Diversity in psychiatry: Or, why did we become psychiatrists? Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:673–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Recollections of a journey through a psychotic episode: Or, mental illness and creativity. Mens Sana Monogr. 2007;5:188–96. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.32163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.APA 2013. Let's Talk Facts Brochures. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.psychiatry.org/mentalhealth/lets-talk-facts-brochures .

- 7.Bennett MR. Development of the concept of mind. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:943–56. doi: 10.1080/00048670701689477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeker H, Richter A, Himmighoffen H, Ernst J, Bohleber L, Hofmann E, et al. Essentials of psychoanalytic process and change: How can we investigate the neural effects of psychodynamic psychotherapy in individualized neuro-imaging? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:355. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BPS 2013. FAQs. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 29]. Available from: http://bombaypsych.org/faqs/faqs.html .

- 10.Buchheim A, Labek K, Walter S, Viviani R. A clinical case study of a psychoanalytic psychotherapy monitored with functional neuroimaging. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:677. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castelnuovo G. Empirically supported treatments in psychotherapy: Towards an evidence-based or evidence-biased psychology in clinical settings? Front Psychol. 2010;1:27. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaimowitz G. Psychotherapy training of psychiatrists. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers A. Mental illness and the developing world. theguardian.com, Monday 10 May. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 30]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/may/10/mental-illness-developing-world .

- 14.Charney DS, Nestler EJ, editors. 3rd ed.(PB) New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. Neurobiology of Mental Illness. [Google Scholar]

- 15.CNN. How to Win a Nobel Prize. CNN.com. Oct. 5, 2006. (Jan. 12, 2012) [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 29]. Available from: http://edition.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/europe/10/04/shortcuts.nobelprize/index.html .

- 16.Crivellato E, Ribatti D. Soul, mind, brain: Greek philosophy and the birth of neuroscience. Brain Res Bull. 2007;71:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doherty P. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006. The Beginner's Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolan B. Soul searching: A brief history of the mind/body debate in the neurosciences. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.23.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drell MJ. The impending and perhaps inevitable collapse of psychodynamic psychotherapy as performed by psychiatrists. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2007;16:207. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, Araya R, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1592–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60891-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.English M. How do you win a Nobel Prize? [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 30]. Available from: http://science.howstuffworks.com/dictionary/awards-organizations/win-nobel-prize.htm .

- 22.Frances A. Why psychiatry is handicapped today. Nov 5, 2013. Medpage Today's KevinMD. com. [Last accessed on 2013 30 Dec]. Available from: http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2013/11/psychiatry-handicappedtoday.html .

- 23.Frese FJ. Coping With Schizophrenia. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 20];Innov Res. 1993 2(3) Available from: http://www.mentalhealth.com/story/p52-sc04.html . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs T, Schlimme JE. Embodiment and psychopathology: A phenomenological perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:570–5. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283318e5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fulford KW, Thorton T, Graham G. 1st Indian ed. New Delhi: Oxford; 2007. Oxford textbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbard GO. Mind and brain in psychiatric treatment. Bull Menninger Clin. 1994;58:427–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabbard GO. Mind and brain in psychiatric treatment. In: Gabbard GO, editor. Treatments of psychiatric disorders. 2nd sub ed. Vol. 1. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Bros; 1999. pp. 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg UC, Garg K. Speaking to a wider audience about the positive contributions of psychiatry. Mens Sana Monogr. 2014;12:71–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.130297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garland EL, Howard MO. Neuroplasticity, psychosocial genomics, and the biopsychosocial paradigm in the 21st century. Health Soc Work. 2009;34:191–9. doi: 10.1093/hsw/34.3.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Georgieff N. Psychoanalysis and social cognitive neuroscience: A new framework for a dialogue. J Physiol Paris. 2011;105:207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.GOI 2011. Size, growth rate and distribtion of population, Census report 2011. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Government of India. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 30]. Available from: http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/india/Final_PPT_2011_chapter3.pdf .

- 32.Groleger U. Pharmacotherapy for the soul and psychotherapy for the body. Psychiatr Danub. 2007;19:206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann HP. Psychoanalytic self psychology and its conceptual development in light of developmental psychology, attachment theory, and neuroscience. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1159:86–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henningsen P, Rudolf G. The use of evidence-based medicine in psychotherapeutic medicine. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2000;50:366–75. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes J, Mizen S, Jacobs C. Psychotherapy training for psychiatrists: UK and global perspectives. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:93–100. doi: 10.1080/09540260601080888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.IGDA WORKGROUP, WPA. IGDA. Introduction. Br J Psychiatry. 2003a;182:S37–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IGDA WORKGROUP, WPA. IGDA 1.Conceptual bases - historical, cultural and clinical perspective. Br J Psychiatry. 2003b;182:S40–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.IPS 2013. Patient information. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.ips-online.org/page.php?p=58 .

- 39.Jebadurai J. One psychiatrist per 200,000 people. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/members/overseasblogs/india/onepsychiatristper200,000.aspx .

- 40.Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, et al. Human resources for mental health care: Current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378:1654–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandel ER. A new intellectual framework of psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:457–69. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandel ER. Biology and the future of psychoanalysis: A new intellectual framework for psychiatry revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:505–24. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kandel ER, Squire LR. Neuroscience: Breaking down scientific barriers to the study of brain and mind. Science. 2000;290:1113–20. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kate 2013. Academic life and mental illness is not a smooth ride but it can be done. May 15. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.time-to-change.org.uk/blog/academic-life-mental-illness .

- 45.Kessler H, Stasch M, Cierpka M. Operationalized psychodynamic diagnosis as an instrument to transfer psychodynamic constructs into neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:718. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khandelwal SK, Jhingan HP, Ramesh S, Gupta RK, Srivastava VK. India mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2004;16:126–41. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001635177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chisholm D, Flisher AJ, Lund C, Patel V, Saxena S, Thornicroft G, et al. Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: A call for action. Lancet. 2007;370:1241–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leichsenring F. Are psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies effective.: A review of empirical data? Int J Psychoanal. 2005;86:841–68. doi: 10.1516/rfee-lkpn-b7tf-kpdu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leichsenring F, Abbass A, Luyten P, Hilsenroth M, Rabung S. The emerging evidence for long-term psychodynamic therapy. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013;41:361–84. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2013.41.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leichsenring F, Rabung S. Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:1551–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.13.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]