Abstract

Metastases resistant to therapy is the major cause of death from cancer. Despite almost 200 years of study, the process of tumor metastasis remains controversial. Stephen Paget initially identified the role of host-tumor interactions on the basis of a review of autopsy records. His “seed and soil” hypothesis was substantiated a century later with experimental studies and numerous reports have confirmed these seminal observations. Inarguably, an improved understanding of the metastatic process and the attributes of the cells selected by this process are critical to the treatment of patients with systemic disease. In many patients, metastasis has occurred by the time of diagnosis, such that metastasis prevention may not be relevant, and treatment of systemic disease, as well as the identity of patients with early disease, should be our goal. During the last three decades, revitalized research has focused on new discoveries in the biology of metastasis. While our understanding of the molecular events that regulate metastasis has improved; nonetheless, the relevant contributions and timing of molecular lesion(s) potentially involved in its pathogenesis remain unclear. The history of pioneering observations and discussion of current controversies should help investigators understand the complex and multifactorial interactions between the host and selected tumor cells that contribute to fatal metastasis and allow for the design of successful therapy.

Keywords: Metastasis, clonal selection, heterogeneity, microenvironment, tumor progression

Introduction

Tumor metastasis is a multistage process during which malignant cells spread from the primary tumor to discontiguous organs (1). It involves arrest and growth in different microenvironments that are treated clinically with different strategies depending on the tumor histiotype and metastatic location. Thus, a single hepatic metastasis may be resected, while bone marrow metastases may be treated with bone targeting radioisotopes. Further, because of cellular heterogeneity, therapeutics have varying efficacy challenging the oncologist and our understanding of the metastatic process (2). Non-malignant cells, under steady state conditions, proliferate as needed to replace themselves as they age or become injured. However, this can go awry, resulting in uncontrolled proliferation and tumor formation, which can be benign or malignant. Benign tumors are generally slow growing, enclosed within a fibrous capsule, noninvasive, and morphologically resemble their cellular precursor. If a benign tumor is not close to critical vascular or neural tissue, prompt diagnosis and treatment frequently results in a cure. In contrast, malignant tumors rarely encapsulate, grow rapidly, invade regional tissues, and have morphologic abnormalities, such that their tissue of origin may be unrecognizable. Further, malignant tumors metastasize, that is, “the transfer of disease from one organ or part to another not directly connected to it” (3). The term “metastasis” was originally coined in 1829 by Jean Claude Recamier (1) and is the defining hallmark of a malignant tumor. It is also the primary clinical challenge as it is unpredictable in onset and because it exponentially increases the clinical impact to the host.

Metastasis has occurred by the time of diagnosis in many patients, although inherent to diagnostic limitations, we may not be aware of this clinically (4). Clinical and pathological observations have revealed that although tumor metastasis can occur early in tumor progression when the primary tumor is small or even undetectable, most do so later when the primary tumor is larger. This is supported by the observation that surgical excision of smaller lesions is often curative and forms the basis for tumor, nodes, metastasis (TNM) staging. Because metastasis has occurred by diagnosis in many patients, therapeutic strategies targeting tumor cell invasion and other early aspects of the metastatic process may not be relevant to outcome. The suggestion, based on microarray analysis, that all tumor cells within a malignant tumor are equally metastatic, is also likely not to be correct (5-7). This controversial conclusion is associated with the low sensitivity of microarray data that supports the similarity of primary and metastatic tumor expression signatures are similarly due to the activation of a metastatic genetic program in early progenitors. Based on this arguable conclusion, it has been suggested that the overgrowth and dominance within primary and secondary lesions by a single tumor cell population, with a uniform metastatic signature, is associated with early metastasis. An extension of this hypothesis is that the late emergence of metastatic clones will result in divergent expression patterns between primary tumors and metastases, secondary to the masking of metastatic signatures in the primary tumor, by persisting nonmetastatic clones (8). However, studies of clonal cell lines derived from a late-stage human carcinomas (9) have provided direct evidence that individual cancer cells, co-existing within a tumor, differ in their metastatic capability including ones that are nonmetastatic, confirming the tumor heterogeneity demonstrated in preclinical studies with murine (10-13) as well as human tumors (14). Furthermore, the expression signatures of tumors derived from cloned weakly/non-metastatic human cell lines and from their isogenic metastatic counterparts from the same patient tumors differ, although the expression signature of metastases and their corresponding primaries are similar (15).

The pathogenesis of metastasis involves a series of steps, dependent on both the intrinsic properties of the tumor cells and the host response (16). The role of host–tumor cell interactions was identified in 1889 by the English surgeon, Stephen Paget (17). He addressed the question, “What is it that decides what organs shall suffer in a case of disseminated cancer?” (17). Based on a review of autopsy records from 735 women with fatal breast cancer, he was able to propose an answer. In addition, he remarked on the discrepancy between the blood supply and frequency of metastasis to specific organs. This included a high incidence of metastasis to the liver, ovary, and specific bones, and a low incidence to the spleen. His observations contradicted the prevailing theory of Virchow (18) that metastasis could be explained simply by the arrest of tumor-cell emboli in the vasculature. Paget concluded that “remote organs cannot be altogether passive or indifferent regarding embolism” and elaborated upon the “seed and soil” principle, stating: “When a plant goes to seed, its seeds are carried in all directions, but they can only live and grow if they fall on congenial soil.” He also suggested that, “All reasoning from statistics is liable to many errors. But, the analogy from other diseases seems to support what these records have suggested, the dependence of the seed upon the soil” (17). Forty years later, in 1928, James Ewing challenged the “seed and soil” hypothesis (19). He proposed that mechanical forces and circulatory patterns between the primary tumor and the secondary site accounted for organ specificity. The seminal studies by Isaiah Fidler and co-workers in the late 1970s and early 1980s conclusively demonstrated that, although tumor cells traffic through the vasculature of all organs, metastases selectively develop in congenial organs (10, 20).

The studies in the late 70s and early 80s (10-13, 20-26) stimulated research into the pathobiology of metastasis, resulting in extensive research into the local microenvironment, or ‘niche,’ of the primary tumor and metastatic foci. They also provided new insight into biological heterogeneity, the metastasis phenotype, and the selection of metastatic variants during or by the process of metastasis (10). Thus, the studies of Paget remain a basis for ongoing research and continue to be cited 120 years following publication. The “seed and soil” hypothesis is now widely accepted although the “seed” may now be identified as a progenitor cell, initiating cell, cancer stem cell, or metastatic cell, and the “soil” discussed as a host factor, stroma, niche, or organ microenvironment (27). Regardless, few currently disagree that the outcome of metastasis is dependent on interactions between tumor cells and host tissue. Similar to Paget's seed and soil hypothesis, Fidler's studies have withstood the test of time and have been repeatedly verified and validated. These results focused on the process of metastasis being sequential and selective with stochastic elements, i.e., the three S's (28). This concept was initially controversial and has provided a lightening rod on which new concepts and hypotheses have been tested (21). Inarguably, at least to a pathologist, malignancy is not a characteristic shared by all cells within a tumor. This may seem obvious; however, recent literature includes discussions where the term “malignant” is used as a synonym for “neoplastic” or “tumorigenic.” Indeed, given the myopia associated with historical literature, researchers continue to rediscover, frequently under new synonyms, classical observations. Unfortunately, these “new” observations do not always incorporate the detailed understanding of tumor biology and experimental designs critical to research into malignancy and metastasis. Studies focused on metastasis require both in vivo and pathologic analyses. In the absence of whole animal studies, the potential for misinterpretation is high. It is incontestable that concepts regarding metastasis must incorporate a detailed understanding of tumor biology and experimental design(s) as malignancy and metastasis are biologic phenomena and can only be described based on in vivo analysis.

The Pathogenesis of Metastasis

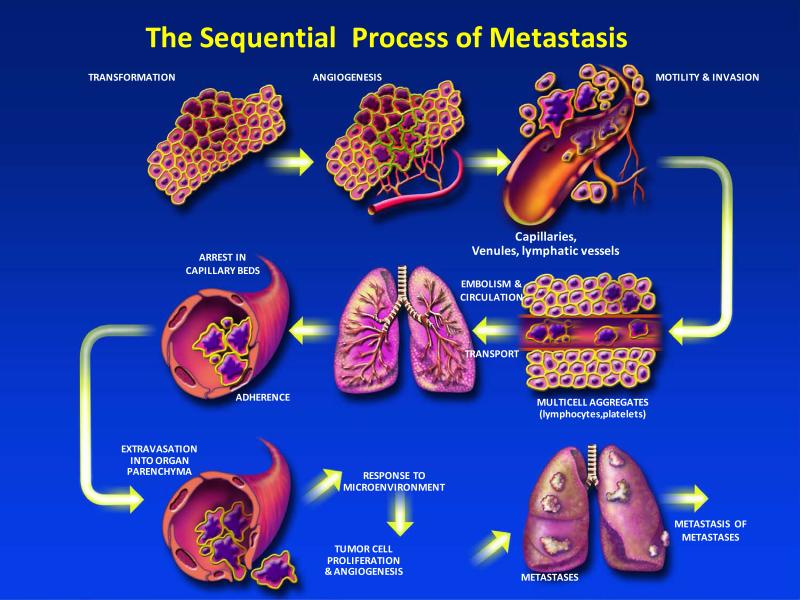

The process of cancer metastasis consists of sequential and interrelated steps (Figure 1), each of which can be rate-limiting since a failure at any step may halt the process (16). Further, the outcome of the process is dependent on both the intrinsic properties of the tumor cells and the host response, such that metastasis is a balance of host-tumor cellular interactions that can vary between patients (29). In principle, the steps or events required for metastasis are the same for all tumors and incorporate the steps shown in Table 1. Thus, the outgrowth of a metastatic lesion requires that it develop a vascular network, evade the host's immune response (30), and respond to organ-specific factors that influence their growth (31-33). Once they do, the cells can again invade the host stroma, penetrate blood vessels, and enter the circulation to produce secondary metastases, or so-called “metastasis of metastases” (16, 34, 35). One critical aspect of this process is the role of the arresting organ. As identified in the seed and soil hypothesis, some organs can support the survival and growth of the tumor emboli or limit its survival. Further, blood flow characteristics and the structure of the vascular system can also regulate the patterns of metastatic dissemination (36, 37). Autopsy studies of breast and prostate cancer patients support an increased number of bone metastases based on blood flow. Thus, some tumor-organ pairs of metastasis may have a positive relationship with metastasis formation (38) and some may be associated with blood flow patterns (39).

Figure 1.

The process of cancer metastasis consists of sequential, interlinked, and selective steps with some stochastic elements. The outcome of each step is influenced by the interaction of metastatic cellular subpopulations with homeostatic factors. Each step of the metastatic cascade is potentially rate limiting such that failure of a tumor cell to complete any step effectively impedes that portion of the process. Therefore, the formation of clinically relevant metastases represents the survival and growth of selected subpopulations of cells that preexist in primary tumors.

Table 1.

Steps in the Metastatic Process

| 1. | After the initial transforming event, the growth of neoplastic cells is progressive and frequently slow; |

| 2. | Vascularization is required for a tumor mass to exceed a 1-2 mm diameter (202) and the synthesis and secretion of angiogenesis factors has a critical role in establishing a vascular network within the surrounding host tissue (202); |

| 3. | Local invasion of the host stroma by tumor cells can occur by multiple mechanisms; including, but not limited to thin-walled venules and lymphatic channels, both of which offer little resistance to tumor cell invasion (203); |

| 4. | Detachment and embolization of tumor cell aggregates that may be increased in size via interaction with hematopoietic cells within the circulation; |

| 5. | Circulation of these emboli within the vascular; both hematologic and lymphatic; |

| 6. | Survival of tumor cells that trafficked through the circulation and arrest in a capillary bed; |

| 7. | Extravasation of the tumor embolus, by mechanisms similar to those involved in the initial tissue invasion; |

| 8. | Proliferation of the tumor cells within the organ parenchyma resulting in a metastatic focus. |

| 9. | Establish vascularization, and defenses against host immune responses; and |

| 10. | Reinitiate these processes for the development of metastases from metastases. |

Only a few cells in a primary tumor are believed to be able to give rise to a metastasis (22, 40). This is due to the elimination of circulating tumor cells that fail to complete all the steps in the metastatic process. The complexity of this progression explains, in part, why the metastatic process was suggested to be inefficient (38). For example, the presence of tumor cells in the circulation does not predict that metastasis will occur as most of the tumor cells that enter the blood stream are rapidly eliminated (22). The intravenous injection of radiolabeled B16 melanoma cells revealed that by 24 hours after injection into the circulation, ≤0.1% of the cells were still viable, and <0.01% of tumor cells within the circulation survived to produce experimental lung metastases (22). Observations such as this raise the question as to whether the development of metastases are the fortuitous survival and growth of a few neoplastic cells, or represent the selective growth of a unique subpopulations of malignant cells with properties conducive to metastasis. That is, can all cells growing in a primary tumor produce secondary lesions, or do only specific and unique cells possess the properties required to enable them to metastasize? While this question has largely been addressed in rodents, clinical studies of this process have been more difficult. Thus, this has been debated; however, recent data shows that human neoplasms are biologically heterogeneous (41-43) and that the process of clinical metastasis is selective (44, 45).

The presence of tumor cells or emboli distant to the primary tumor does not prove that metastasis has occurred. Circulating tumor cells are rapidly eliminated, and arrest in a capillary bed or the marrow is not indicative that a metastatic focus will or has formed. Indeed, cellular arrest during the metastatic process frequently results in cellular apoptosis, dormancy and, more rarely, a clinically detectable metastasis. Thus, the process of metastasis is inefficient, seldom exceeding 0.01% (22), while the entry of tumor cells into the circulation is common and more than a million cells per gram of tumor can be shed daily (46). The low frequency of secondary foci was documented by Tarin et al. using peritovenous shunts to reduce ascites in women with ovarian cancer (47). Although millions of tumor cells were directly deposited into the vena cava every 24 hours by the shunt, these women rarely developed secondary tumors. Similarly, the finding of epithelial cells within the marrow of patients with breast cancer has prognostic indications (48). However, not all cells within the marrow form metastatic nodules due, in part, to host responses against the tumor cells. Thus, antitumor host response can contribute to a soil incapable of supporting tumor cell growth and/or associated with the development of tumor dormancy.

The process of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis is not rapid, and tumor growth rates are generally slow. Mammography studies (49, 50) have shown that primary breast tumors have an average doubling time of 157 days (32) varying between 44 and >1,800 days during exponential growth (51). Thus, the growth of a tumor from initiation to a size of 1-cm (52), which is the limitation of most current imaging tools, requires an average of 12 years. This is significant as a one centimeter diameter tumor has 109 cells and has undergone at least 30 doublings from tumor initiation to diagnosis (4). Based on these parameters and the observation that a tumor burden of approximately 1,000-cm3 is generally lethal (53), the time from diagnosis to mortality represents 10 doubling times from a 1-cm tumor and a shorter time frame. Thus, three quarters of a tumor's life history has occurred prior to diagnosis, and metastasis can occur prior to diagnosis. Similarly, a tumor embolus associated with a surgical shower would require 10 to 12 years to grow to a 1-cm metastasis. These timelines are supported by registry data, which suggests that the median time from tumor resection to a diagnosis of metastasis for patients with a T1 (<2 cm) tumor is 35 months versus 19.9 months for patients with a T3 (>5 cm) tumor (54). Further, these data support the suggestion that metastasis can occur years prior to diagnosis. The time required for the development of a malignant tumor and progression from an adenoma to a malignant carcinoma may be longer than the progression of an adenoma to a metastasis. This may be because more mutations and clonal expansion(s) are required for progression to malignancy as compared to the number required to form a metastasis (55). The time between the appearance of a small adenoma and the diagnosis of malignancy may be as long as 20–25 years based on studies in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (56), and confirmed by serial studies of sporadic colorectal cancer that revealed the transition from a large adenoma to carcinoma takes about 15 years (57). These estimates are consistent with the doubling times of tumors, determined by serial radiologic studies and serial measurements of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) serum biomarker (58). This differs from the observed mean doubling times of a metastasis that may be 2-4 months (55).

The Organ Microenvironment

Clinical observations of cancer patients and studies in rodent models of cancer have revealed that some tumor phenotypes tend to metastasize to specific organs, independent of vascular anatomy, rate of blood flow and number of tumor cells delivered to an organ. Experimental data supporting Paget's ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis have been derived from studies on the invasion and growth of B16 melanoma metastases in specific organs (20). In these studies, melanoma cells were injected intravenously (i.v.) into syngeneic mice with tumor foci development in the lungs and in fragments of pulmonary or ovarian tissue implanted intramuscularly. In contrast, metastatic lesions did not develop in implanted renal tissue, or at the site of surgical trauma, suggesting that metastatic sites are not solely determined by neoplastic cell characteristics, or host microenvironment (20). Ethical considerations rule out experimental analysis of cancer metastasis in patients, but the use of peritoneovenous shunts for the palliation of ascites in women with progressive ovarian cancer has provided an opportunity to study factors that affect metastatic spread in humans (47). Human ovarian cancer cells can grow in the peritoneal cavity, either in the ascites fluid or by attaching to the surface of peritoneal organs. These malignant cells, however, do not metastasize to other visceral organs. One (incorrect) explanation for the lack of visceral metastases is that tumor cells cannot gain entrance into the systemic circulation. Studies by David Tarin and colleagues into metastasis by ovarian tumors in patients whose ascites were drained into the venous circulation addressed this question (47). Clinically, this resulted in palliation with minimal complications; although, the procedure allowed the entry of viable cancer cells into the jugular vein. Autopsy findings from 15 patients substantiated the clinical observations that the shunts did not significantly increase the risk of metastasis to organs outside the peritoneal cavity. Indeed, despite continuous entry of millions of tumor cells into the circulation, metastases to the lung, the first capillary bed encountered, were rare (47). These results provide compelling verification of the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis. Organ specific metastases have also been demonstrated in studies of cerebral metastasis after injection of syngeneic tumor cells into the internal carotid artery of mice. Differences between two mouse melanomas were found based on patterns of brain metastasis such that the K-1735 melanoma produced lesions in the brain parenchyma (59) and the B16 melanomas produced meningeal metastases (60). Thus, different sites of tumor growth within an organ include differential interactions between metastatic cells and the organ environment, possibly in terms of specific binding to endothelial cells and responses to local growth factors (61).

Seed and Soil

Since the 1980s, many investigators have contributed to our understanding of cancer pathogenesis and metastasis, and the dependency of these processes on the interaction between cancer and homeostatic factors (62). Our concept of the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis consists of three principles. The first principle is that primary neoplasms (and metastases) consist of both tumor cells and host cells. Host cells include, but are not limited to, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and infiltrating leukocytes. Moreover, neoplasms are biologically heterogeneous and contain genotypically and phenotypically diverse subpopulations of tumor cells, each of which has the potential to complete some of the steps in the metastatic process, but not all. Studies using in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical staining have shown that the expression of genes/proteins associated with proliferation, angiogenesis, cohesion, motility, and invasion vary among different regions of neoplasms (62, 63). Due to the heterogeneity of tumors and the tumor infiltration by “normal” host cells, the search for genes/proteins that are associated with metastasis cannot be conducted by the indiscriminate and nonselective analysis of tumor tissues.

The second principle is that a focused analyses into the metastatic process is needed to reveal the selection of cells that succeed in invasion, embolization, survival in the circulation, arrest in a distant capillary bed, and extravasation into and multiplication within organ parenchyma (Figure 1). These successful metastatic cells (‘seed’) have been likened to a decathlon champion who must be proficient in 10 events, rather than just a few (64). However, some steps in this process incorporate stochastic elements. Overall, metastasis favors the survival and growth of a few subpopulations of cells that preexist within the parent neoplasm. The current data, especially studies focused on isolated tumor cells, support a clonal origin for metastases, such that different metastases originate from different single cells (21, 64). The third principle is that metastatic development occurs in specific organs, or microenvironments (‘soil’), that are biologically unique. Endothelial cells in the vasculature of different organs express different cell-surface receptors (65) and growth factors that can support or inhibit the growth of metastatic cells (66). Thus, the outcome of metastasis depends on multiple interactions (‘crosstalk’) of metastasizing cells with homeostatic mechanisms, such that the therapy of metastases can target not only the cancer cells, but also the homeostatic factors that promote tumor-cell growth, survival, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis (67).

As discussed above, the analysis by Stephen Paget showed that breast tumors preferentially spread to the liver, but not the spleen. The bone marrow is also a preferential target for breast cancer metastases, with some patients developing metastases more frequently than others. These observations (68, 69) identify that the site of secondary tumors is dependent on the tumor cell (“seed”) and the target organ (“soil”). Therefore, a metastatic focus is established only if the seed can grow in the soil, i.e., if the microenvironment of the target site is compatible with the properties and requirements of the disseminated tumor cell. While this hypothesis was challenged (70), it is now largely accepted that the anatomic architecture of the blood flow is not sufficient to fully describe the patterns of metastatic tumor spread. There are several, molecular and cellular explanations that support the seed and soil hypothesis. These include the observations that endothelial cells lining blood vessels in different organs express different adhesion molecules (61) results from in vivo phage display studies suggest that every vascular bed may have its own specific molecular “address” (71), and the observation that tumor cells expressing the corresponding receptor may use these receptor-ligands to traffic to and arrest in specific tissues. There is also compelling evidence supporting a role for chemokines in the homing or chemoattraction of organ-selective metastasis (72). The CXCR4 receptor appears to have a role in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, and pulmonary targeting of metastases from breast tumors that express its ligand, CXCL12 (73). CXCR4 regulates chemotaxis in vitro and CXCR4-blocking antibodies have been shown to impair lung metastasis in SCID mouse xenograft experiments (72). However, in vivo, CXCR4 activation can also promote the outgrowth of metastases in specific tissues rather than invasion (74). Recently, an immunohistochemical analysis of CXCL12 expression in tumor endothelial cells was reported to have a significant correlation with survival in patients with brain metastases (75). Additional support for organ specific targeting has come from the gene-expression analysis of breast cancer cells selected for increased metastasis to bone (76) or lungs (77) that identified genes functionally involved in organ-specific metastasis.

Cellular Infiltration of Tumors and Metastases

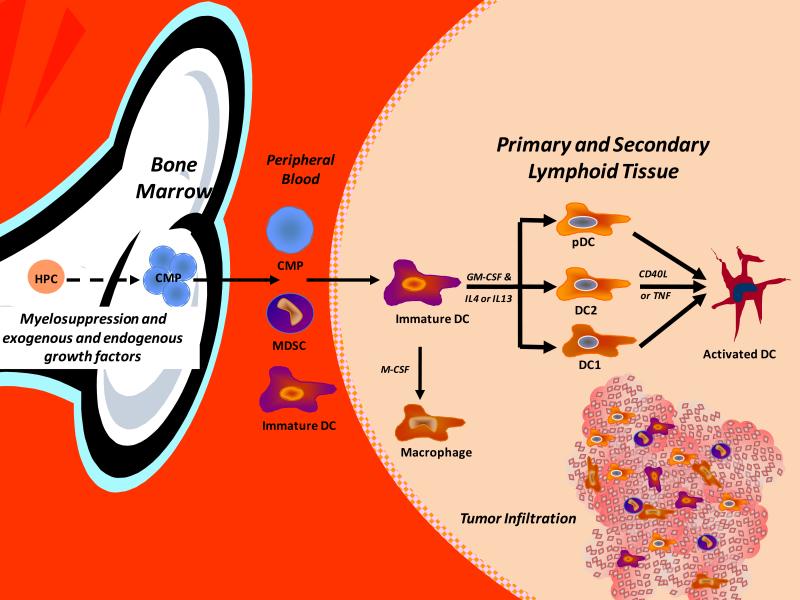

The role of tumor infiltration by leukocytes in tumor growth and development is complex. Although tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) have tumoricidal activity and can stimulate antitumor T-cells, tumor cells can block inflammatory cell infiltration and the function of infiltrating cells (78). Tumor-derived molecules can regulate the expansion of myeloid progenitors (Figure 2), their mobilization from the marrow, chemo-attraction to tumors and activation resulting in the promotion of tumor survival, growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Numerous studies have demonstrated that following activation, macrophages can kill tumor cells in vitro (79). Indeed, if a macrophage activating agent is injected prior to isolation of macrophages from metastases, they have tumoricidal activity in vitro (79). However, tumor infiltration by macrophages appears to have predominately a pro-tumorigenic/metastatic phenotype. This was initially shown in a study in which the macrophage content of six carcinogen-induced fibrosarcomas was reported to directly correlate with immunogenicity and inversely with metastatic potential (80). Other studies using human breast carcinomas and melanomas have been equivocal (81). One clinical study showed that patients with metastatic disease had a low macrophage infiltration (≤10%) of their primary neoplasm, while 13 patients with benign tumors and 6 out of 31 patients with malignant tumors and no clinical evidence of metastases had a TAM frequency of ≥10% (81). Thus, most (82-84) but not all studies (85) have shown that there is no relationship between immunogenicity, metastatic propensity, and TAM frequency. Macrophages differentiate from CD34+ bone marrow (BM) progenitors following expansion and commitment and are mobilized from the marrow into the periphery (56, 86), where they differentiate into monocytes and following invasion into a tissue, mature into macrophages (87). Macrophage infiltration of primary tumors is regulated, at least in part, by cytokines, growth factors (GFs), and enzymes secreted by the primary tumor. The primary tumor can also regulate the function of TAMs, including tumor cell cytotoxicity, which can be tumor-dependent (88).

Figure 2.

Tumors can secrete growth factors and cytokines that result in the expansion and mobilization of myeloid progenitors from the marrow with trafficking to various extramedullary sites including the spleen, liver, lungs and primary and metastatic tumor lesions. These committed myeloid progenitors (CMP) can mature into dendritic cells (DCs) myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and macrophages including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as well as become activated, or “paralyzed”, within the tumor environment. These heterogeneous cells include progenitor cells, immature cells, mature, and activated cells. Dependent upon the infiltrating subset and extent of maturation and activation, these cells can be a critical component and regulator of angiogenesis, vascularogenesis, and tumor regression or growth.

Clinical studies of macrophage infiltration of tumors have suggested that this does not correlate with the immunogenicity and metastatic propensity (82-84, 89); rather, it is associated with a poor prognosis (90). Thus, a low frequency of macrophage infiltration does not guarantee that a tumor will metastasize as multiple factors are critical (91). Macrophage infiltration of tumors is regulated by tumor-associated chemoattractants such that host/tumor interactions may result in qualitative (88) or quantitative (92) regulation of macrophage infiltration that can be obscured by the technologies used to assess macrophage infiltration (83, 93). Macrophages present in the extracellular matrix and capsular area of tumors can facilitate tumor invasion and are important during the development of early stage lesions (94). Further, the proteolytic enzyme secreted by activated macrophages facilitates tumor invasion and extravasation. Indeed, in vitro co-culture of macrophages with tumor cells can accelerate tumor growth (95). Macrophage infiltration of some tumor models has been found to inversely correlate with relapse-free survival (RFS), microvessel density, and mitotic index (96). TAMs also express a number of factors (97) that stimulate tumor cell proliferation and survival and support angiogenesis, a process essential for tumor growth to a size larger than the 1-2 mm3 size that can occur in the absence of angiogenesis.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have also been identified in the circulation of tumor bearing hosts and infiltrating tumors. MDSCs in mice are CD11b+Gr-1+ (98, 99), while the human equivalents that were originally described in the PB of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck patients (100) and, more recently, other cancer histiotypes, are DR−CD11b+ (100-102). Tumor growth is associated with the expansion of this heterogeneous cellular population, which can inhibit T-cell number and function. The mechanisms of MDSC immunosuppression are diverse, including upregulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO) production, L-arginine metabolism, as well as secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines. The immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs were initially described in the late 1970s when they were identified as natural suppressor (NS) cells and defined as cells without lymphocyte-lineage markers that could suppress lymphocyte response to immunogens and mitogens (103, 104).

GM-CSF has been directly associated with MDSC-dependent T-cell suppression (98), which can be reversed by blocking antibodies (105). Mice bearing transplantable tumors that secrete GM-CSF have increased numbers of MDSC and suppressed T cell immunity (106), a finding that contrasts with the adjuvant activity of GM-CSF for tumor vaccines (107). This difference is associated with GM-CSF levels such that high levels expand MDSC numbers and reduce vaccine responses, while lower levels augment tumor immunity. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has also been directly linked with MDSC expansion and tumor progression (108). VEGF can suppress tumor immunity (109) via an inhibitory effect on dendritic cell (DC) differentiation (110). Thus, there is a correlation between plasma VEGF levels in cancer patients, a poor prognosis (111), and VEGF-induced abnormalities in DC differentiation (112), resulting in an inverse correlation between DC frequency and VEGF expression (113). As expected, neutralizing VEGF antibodies can reverse not only VEGF-induced defects in DC differentiation (113), but also improve DC differentiation in tumor-bearing mice (114).

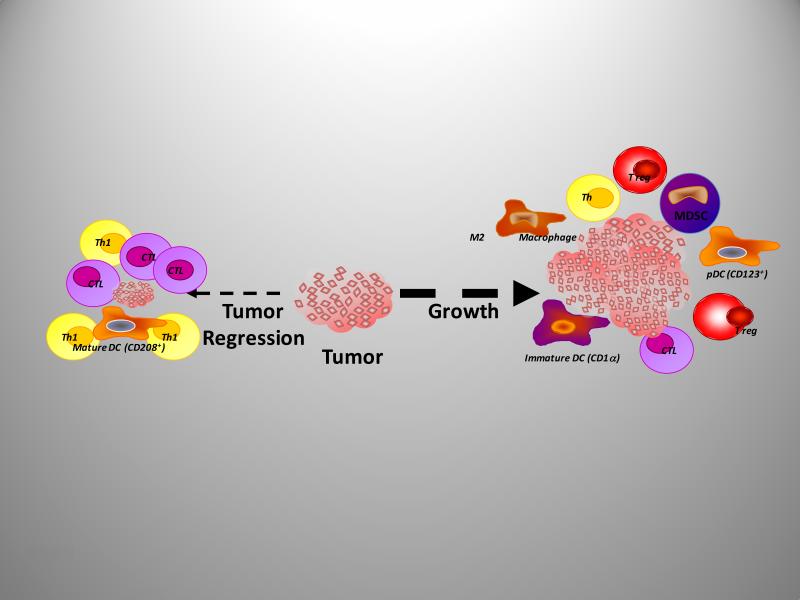

Recently, Dr. Finke (115) reported that administration of sunitinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) resulted in a significant decrease in MDSC within patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (116). Whether this was associated with a reduction in VEGF levels and neoangiogenesis or as an inhibition of Flt3-mediated expansion of MDSC remains to be addressed. Regardless of this observation there have been few studies that examined the infiltration of tumors by MDSC. In one recent rodent study, it was shown that CCL2 mediated MDSC chemotaxis in vitro and that migration or chemotaxis of MDSC could be blocked with neutralizing CCL2 antibodies (Abs) or by blocking CCR2. Sunitinib has also been shown to mediate reversal of MDSC accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients (116). These observations suggest that the regulation of infiltrating myeloid cells has the potential to control the growth of primary tumors and metastasis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The immune cells infiltrating tumors can regulate their growth, progression, and metastasis. Tumor regression is associated with infiltration by mature dendritic cells (DCs) and cytotoxic T cells (CTL) and type 1 T-helper type 1 bioactivity. Contrasting with this, tumor growth is facilitated via immune mediated immunosuppression and neoangiogenesis following infiltration of tumors with immature DCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, (MDSCs) plasmacytoid DCs, (pDCs) M2 macrophages, as well as T regulatory (T-reg) cells and a low frequency of CD4 and CD8 effector T cells.

Metastatic Heterogeneity

Cells with different metastatic properties have been isolated from the same parent tumor, supporting the hypothesis that not all the cells in a primary tumor can successfully metastasize (41-43). Two approaches have been to demonstrate that cells within the parent neoplasm differ in metastatic capacity. In the first approach, metastatic cells are selected in vivo, such that tumor cells are implanted at a primary site or injected i.v., metastases allowed to grow, individual lesions collected and expanded in vitro, and these cells used to repeat the process. This cycle is repeated several times and the function of the cycled cells compared with that of cells from the parent tumor to determine whether the selection process resulted in an enhanced metastatic capacity (117). Several studies have demonstrated that the increase in metastatic capacity did not result from the adaptation of tumor cells to preferential growth in a specific organ but, rather, was due to selection (23, 24, 118). This procedure was originally used to isolate the B16-F10 line from the wild-type B16 melanoma (117), but has also been successfully used to produce tumor cell lines with increased metastatic capacity from many murine and human tumors (119, 120).

In the second approach, cells are selected for an enhanced expression of a phenotype believed to be important to a step in the metastatic process and are then tested in vivo to determine whether their metastatic potential has changed. This method has been used to examine properties as diverse as resistance to T lymphocytes (121), adhesive characteristics (122), invasive capacity (123, 124), lectin resistance (125), and resistance to natural killer cells (126). The finding that a characteristic, typically utilizing a single tumor model with only one or two variants, is associated with metastasis is often considered as proof that this parameter is directly responsible for metastasis. However, this can be model dependent, associated with the selective procedure and has resulted in conclusions and associations that are not reproducible. Clearly, numerous phenotypes are associated, in part, with the metastatic process, but rarely represent all the phenotypes critical to the final outcome. Thus, studies of this nature, as well as, comparisons of clonal subpopulations lend insight into phenotypes that may have a role in metastasis, but can lead one astray as regards overall conclusions into the process. This is also true of microarray analyses, whereby, the primary tumor can have multiple cellular phenotypes due to clonal heterogeneity, as well as, the confounding variable of infiltrating “normal” host cells obfuscating conclusions. As such, conclusions, based on a limited number of tumor samples/clones into a process as complex as metastasis, has the potential to be unsupportable.

One criticism of studies into metastatic heterogeneity is that isolated tumor line(s) may have arisen as a result of an adaptive rather than a selective process. This was addressed by the analysis of metastatic heterogeneity by Fidler and Kripke in 1977 using the murine B16 melanoma (10). A modification of the fluctuation assay of Luria and Delbruck (127) showed that different tumor cell clones, each derived from individual cells isolated from the parent tumor, varied in their ability to form pulmonary nodules following intravenous inoculation into syngeneic mice. Control subcloning procedures demonstrated that the observed diversity was not a consequence of the cloning procedure (10). To exclude the possibility that the metastatic heterogeneity found in the B16 melanoma might have been introduced as a result of in vivo or in vitro cultivation, the biologic and metastatic heterogeneity of a mouse melanoma induced in a C3H/HeN mouse was also studied (128). This melanoma designated K-1735 was established in culture and immediately cloned (129, 130). An experiment similar to the that undertaken with the B16 melanoma confirmed that (10) the clones differed from each other and the parent tumor in their ability to produce lung metastases. In addition, the clones differed in metastatic potential, resulting in metastases that varied in size and pigmentation. Metastases to the lungs, lymph nodes, brain, heart, liver, and skin were not melanotic, while those growing in the brain were uniformly melanotic (59, 129, 130).

An extension of studies into metastatic heterogeneity assessed immunologic rejection by a normal syngeneic host (131, 132), as compared to young nude mice (133), a model in which the immunologic barrier to metastasis is removed and antigenic metastatic cells are able to successfully complete the process. In these studies, cells of two clones that did not produce metastases in normal syngeneic mice produced lung metastasis in the young nude mice. However, most of the nonmetastatic clones were nonmetastatic in both normal syngeneic and nude recipients. Therefore, the ability to metastasize in syngeneic mice was primarily not due to immunologic rejection, but by other deficiencies that prevented completion of a step in the metastatic cascade.

The observation that preexisting tumor subpopulations with metastatic properties exist in the primary tumor has been confirmed by many laboratories using a wide range of tumors (16, 26, 30, 53, 134-136). In addition, studies using young nude mice as models for metastasis of human neoplasms have shown that human tumor cell lines and freshly isolated human tumors, such as colon and renal carcinomas, also contain subpopulations of cells with widely differing metastatic properties. Talmadge and Fidler undertook a series of studies to address the question of whether the cells that survive to form metastases possess a greater metastatic capacity than cells in an unselected neoplasm (23, 25, 117). In these studies, cell lines derived from spontaneous metastatic foci were found to produce significantly more metastases than cells from the parent tumor. Studies with heterogeneous, unselected tumors support the hypotheses that metastasis is a selective process, regulated by a number of different mechanisms. It should be noted that metastatic foci can be clonal in origin, yet originate from tumor emboli containing more than a single tumor cell. Tumor emboli composed of heterogeneous tumor cells can arise if an embolus is derived from a non-homologous zone within a primary tumor (137). The zonal composition of a tumor may play a role in the metastatic process, but also has the potential to obscure the results of microarray studies. The zonal composition can result in the appearance of minimal heterogeneity if a sample is obtained from a single zone within a neoplastic lesion. Thus, as recommended by Bachtiary (138), microarray analyses need to consider intratumoral heterogeneity and zonal gene expression, such that multiple tumor biopsies should be studied from discontiguous sites. Moroni et al. (139), using human colorectal carcinomas, reported intratumoral heterogeneity and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene amplification that correlated with protein levels. Experiments using human tumors in nude mice by Pettaway et al. (140) also revealed that orthotopic implementation of heterogeneous human prostate cancer cell lines into nude mice resulted in rapid local growth and distant metastatic foci with an increased metastatic propensity to various organ sites including the GI tract. The clonal origin of these metastatic foci was documented with karyotypic markers extending and confirming the prior studies by Talmadge and Fidler (21).

The Clonal Origin of Metastases

Nowell (141, 142) suggested that acquired genetic variability within developing clones of tumors, coupled with selection pressures, results in the emergence of new tumor cell variants that display increased malignancy. This hypothesis suggested that tumor progression toward malignancy is accompanied by heightened genetic instability of the progressing cells. To test this hypothesis, Maria Cifone measured the mutation rates of paired metastatic and non-metastatic cloned lines isolated from four different murine tumors (143). She found that highly metastatic cells were phenotypically less stable than their benign counterparts. Moreover, the spontaneous mutation rate of the highly metastatic clones was several fold higher than in non- or poorly-metastatic clones. These observations were subsequently confirmed and extended by with other murine (144) and human neoplasms (145, 146). Taken together, these studies suggest that metastatic tumor populations have a greater likelihood of cells undergoing rapid phenotypic diversification. This genetic instability, coupled with a Darwinian selection, may result in populations resistant to normal homoeostatic growth controls, chemotherapeutic intervention, immune attack, and environmental restraints (147). Indeed, this process can be extended by the mutagenic activity of drugs commonly used to treat tumors (148). This biological heterogeneity is found both within a single metastasis (intralesional heterogeneity) and among different metastases (interlesional heterogeneity). The heterogeneity reflects two processes; the selective nature of the metastatic process and the rapid evolution and phenotypic diversification of clonal tumor growth, resulting from the inherent genetic and phenotypic instability of clonal tumor cell populations. Like primary neoplasms, metastases have the potential for a unicellular or multicellular origin. To determine whether metastases arise from the same clone, or whether different metastases are produced from different progenitor cells, Talmadge et al. designed a series of experiments based on the gamma-irradiation induction of random chromosome breaks and rearrangements to serve as “markers” (149). They examined the metastatic phenotype of individually spontaneous lung metastases that arose from subcutaneously implanted tumors (149). In ten metastases, all the chromosomes were normal, making it impossible to establish whether they were of uni- or multicellular origin. In other lesions, unique karyotypic patterns of abnormal marker chromosomes were found, indicating that each metastasis originated from a single progenitor cell. Subsequent experiments showed that when heterogeneous clumps of different melanoma cell lines were injected i.v., the resulting lung metastases were of unicellular origin (21). These studies indicated that regardless of whether an embolus was homogeneous or heterogeneous, metastases originate from a single proliferating cell. The clonality of metastases has also been reported for numerous other tumors, including breast cancer and fibrosarcomas, as well as melanoma (146).

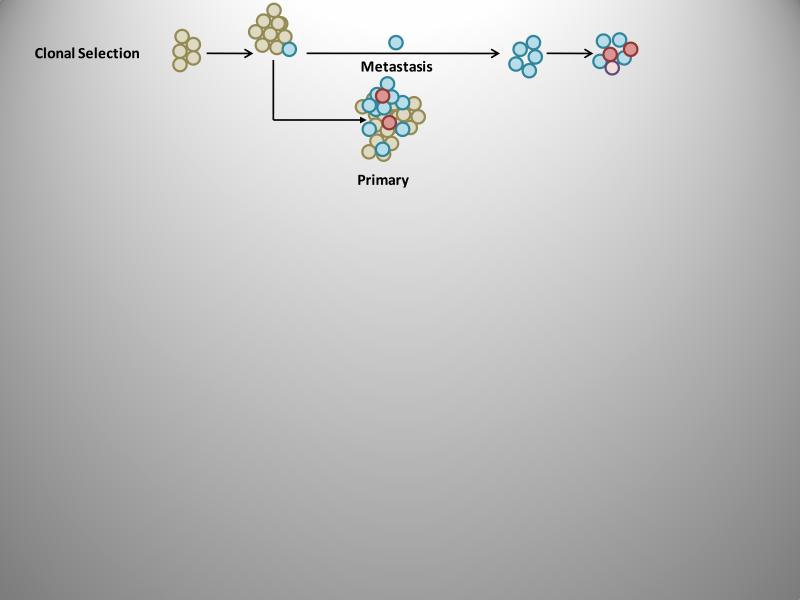

The role of clonal selection (Figure 3) during the process of metastasis and the emergence of successive clonal subpopulations has been supported by studies in which individual cells were tagged by unique markers allowing them to be tracked (150). This has been undertaken with radiation-induced cytogenetic (chromosomal) markers (28) which clearly demonstrated clonal selection. This observation was confirmed by Kerbel and collaborators with the use of drug resistance markers (151) and X-linked isoenzyme mosaicisms (152). However, all of these approaches are limited and recent studies have used markers based on the random insertion of transfected plasmids, which results in the generation of large numbers of uniquely marked cell clones (140, 153, 154). Clearly, clonal selection and intra-host metastatic heterogeneity are supported by preclinical studies (149, 151, 152, 154-156). However, clinical confirmation has been challenging due to methodological impediments. Metastatic tissue is generally obtained asynchronously, relative to primary tumor tissue, and comparisons complicated by tissue availability. Several studies have successfully compared primary tumors to metastatic foci within the same patient based on a number of different phenotypes. Kuukasjarvei et al. (44) analyzed the genetic composition of 29 primary breast carcinomas and paired asynchronous metastases. They found that 69% of the metastases had a high degree of clonality with the corresponding primary tumor, whereas chromosomal X inactivation patterns supported the remaining metastatic lesions as originating from the same clone as the primary tumor. It was concluded that although all metastases were derived from the parent tumor, metastasis occurred at different times. Studies using microarray analyses have also addressed this process and are discussed in the section entitled, “Microarray analysis of heterogeneity, clonality, and prognostic potential.” Results from the microarray and computational analyses have revealed that a small number of genes are differentially expressed between tumors and metastases, supporting the conclusion that although metastases resemble the primary tumor on a mutational basis, a few genes differ consistently and are of significant mechanistic importance.

Figure 3.

The clonal selection model of metastasis suggests that the cell populations in the primary tumor with all of the genetic prerequisites required for metastatic capacity are the subpopulations that metastasize. Further, both the cells within the primary tumor and the metastatic lesion(s) can continue to diversify as the lesions grow.

Current Controversies in Metastatic Research

Pre-metastatic Niche

Recently, it was suggested that to form a metastatic focus, primary tumors produce factors that induce the formation of an appropriate environment in the soil (organ) prior to the seeding of metastatic cells. This led to the concept of a pre-metastatic niche, whereby a special, permissive microenvironment in the secondary site is developed (157). The initial study into a pre-metastatic niche indicated that VEGFR1+ hematopoietic progenitor cells contribute to metastatic spread (158). These VEGFR1+ cells were suggested to arrive at a distant organ site, forming a pre-metastatic niche of clustered bone marrow hematopoietic cells (158). They were suggested to alter the tissue microenvironment and promote the recruitment of tumor cells by the up-regulation of integrins and cytokines. The blockade of VEGFR1 cells in vivo has been suspected to abrogate the formation of pre-metastatic niches and inhibit the growth of metastatic foci. The regulation of VLA-4 and fibronectin by VEGFR1+ cells also helps dictate which organs attract hematopoietic progenitors and support their adhesion; thereby promoting pre-metastatic niches (158). In addition, this may contribute to survival of the metastatic tumor cells as discussed in the section on MDSCs. Mittal and colleagues demonstrated that angiogenesis is essential for the growth of micrometastases (159), and that this process was regulated by bone marrow derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). At the micrometastatic stage, EPCs traffic to and colonize micrometastases. Accelerating angiogenesis facilitates the growth into gross metastases. The blockade of EPCs by short hairpin RNA directed against the Id1 gene, was found to inhibit angiogenesis at the micrometastatic stage and to impair subsequent growth (159). Furthermore, although the number of EPCs contributing to angiogenesis in metastases remained low (in the range of 11%), their impact on the development of micrometastases and rapid cell proliferation is critical for progressive growth of metastasis (160).

Thus, experimental evidence supports the formation of a pre-metastatic niche, which can facilitate metastasis via VEGFR-1+ bone marrow derived hematopoietic progenitor cells (158). These cells express hematopoietic markers, and chemokines and chemokine receptors (e.g., CXCL12/CXCR4), promoting either their homing to the target tissue and/or recruitment /attachment of tumor metastatic cells. This process includes the CXCL12 / CXCR4 axis which has a critical role in stem cell migration (161). Activation of CXCR4 induces motility, chemotactic response, adhesion, secretion of MMPs, and release of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF-A. Thus, disseminating tumor cells, in order to survive at distant sites, need a supportive microenvironment similar to that found in the primary tumor. One way this may occur is by the mobilization and recruitment to a pre-metastatic niche of immune/inflammatory cells that can stimulate growth of metastatic cells (162).

Multiple cellular and molecular mechanisms, whereby tumor cells interact with immune cells, regulate their number and function, and allow tumor cells to escape from immunologic recognition and control (Figure 4). These immunoregulatory events have important physiological and pathophysiological significance, not only for host-tumor interactions and clinical outcomes, but also for clinical intervention. Studies to date have focused on the inflammatory cell infiltration within tumors and draining lymph nodes (LNs) and more recently, subset analyses. T lymphocytic responses to tumors are generally associated with a good prognosis; however, vaccine strategies have had little impact to date (163). This is due, in part, to the escape mechanisms that tumors utilize to circumvent immunologic responses. Host-tumor interactions limit lymphocyte infiltration such that the majority of infiltrating cells are from the innate immune system (164) and are typically immature or with impaired function (163). These cells can “paralyze” the induction of T cell and DC responses (165) in addition to facilitating tumor proliferation and metastasis (166) via pro-angiogenic activity. Indeed, the immune cells infiltrating tumors can secrete immunosuppressive enzymes, resulting in lymphocytic apoptosis and the induction of tolerance (167). Critical questions remain, including how tumors become refractory to immune intervention strategies to overcome these immunosuppressive mechanisms.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMTs)

Molecular technologies, including DNA, antibody, and proteomic arrays, and short-hairpin RNA libraries, have been used to identify multiple molecules that contribute to the metastatic process. This includes growth factors, cytokines and chemokines, pro-angiogenic factors, extracellular matrix-remodeling molecules and, most recently, transcription factors that may regulate cellular changes during tumor invasion-metastasis. These transcription factors include Slug, Snail, Goose-coid, Twist, and ZEB1, which are highly expressed by metastatic cells and have been suggested to have a role in inducing EMTs (168-171), defined as a rapid and reversible change in cellular phenotypes. This concept originated from studies into embryologic development, including the change in phenotype and behavior of cells invaginating from the surface into the interior of an embryo to form the mesoderm during gastrulation (172), changes during renal organogenesis, and the origin and fate of the neural crest (173). EMT studies have focused on the invasive behavior and spindling of cultured cells (174) using explanted embryonic tissue (175). Thus, the potential relevance of EMT to tumor progression is largely based on in vitro studies (176), using transformed epithelial cells and growth factors or extracellular matrix manipulations. Genes upregulated during tumor progression and metastasis are associated with multiple processes, including embryogenesis, tissue morphogenesis, and wound healing (177). In neoplasia, EMT is suggested to result in the loss of epithelial properties, including cell-cell adhesion and baso-apical polarity, and the gain of mesenchymal properties, such as an increased ability to migrate on and invade through extracellular matrix proteins (177). EMT has also been associated with the loss of expression and/or mis-localization of proteins involved in the formation of cell-cell junctions, such as E-cadherin, zonula occludens (ZO-1) and/or claudin, and the gain of mesenchymal protein expression. Thus, a depression in E-cadherin expression is frequently observed during cancer progression (172), and solid cancers are associated with a loss or down-regulation of E-cadherin expression (172, 178).

EMT has been suggested to have a role in the progression of benign tumor cells to invasive and metastatic cells (172). This suggestion is largely based on cell culture, microarray, and histiologic studies. EMT proponents have suggested that tumors which display malignant histopathologic features including loose, scattered cancer cells, spindle cell cytology, which are more aggressive based on grade, stage, and clinical outcome, support the concept that EMT is mechanistically significant (169). Inarguably, carcinomas are histologically heterogeneous in addition to being infiltrated by mesenchymal cell histiotypes. The histiologic identification of mesenchymal elements in human tumors, identified as fetal-type fibroblasts and malignant stroma was described years ago (179). Indeed, a collection of 100 dual staining spindle cell breast carcinomas was reported in 1989 (180). Further, antibodies against keratin 14 and smooth muscle actin have identified spindle cell elements, which may or may not be clinically significant (181, 182). Foci with a histologic appearance of EMT are found in human tumors and this anaplastic appearance, including loss of cell polarity and lineage specific or tissue specific cytology are common features of carcinomas. The morphologic disorder, pleomorphism, and anaplasia as observed by an unskilled observer may be suggestive of a mesenchymal lineage. The examples cited as evidence of EMT in clinical neoplasms, including: scattered single cell infiltration by lobular carcinomas of the breast (172) or diffuse carcinomas of the stomach (183), spindle cell differentiation in squamous carcinomas, and blending of sheets of carcinomatous cells into a highly cellular, desmoplastic stroma without a clear line of demarcation, potentially represent inappropriate analysis of these lesions. As discussed below, diffusely infiltrating cells in lobular carcinomas retain their epithelial identity.

The data supporting EMT, based on in vitro observations, has largely utilized two-dimensional environment that do not contain host stroma, such as vascular, immune, endocrine or neurologic elements. Similarly, studies of cells in three-dimensional matrices do not recapitulate the host environment and the identification of cells in vitro as epithelial or mesenchymal in origin, based on morphology is subjective. Indeed, studies in which epithelial and mesenchymal cell markers are used, to provide evidence for a switch from one differentiated cell lineage to another is also suspect as they relate a marker to a morphologic phenotype, which itself is claimed to transmute into another cell type and thus the identification process becomes self-fulfilling. Inappropriate gene expression by tumors is well established and genetically unstable cells and infiltrating cells could contribute to shifts in linage markers. Indeed, it is difficult to define cells, on morphologic criteria alone, and the gain or loss of markers is insufficient to conclude that a cell population has undergone whole-scale gene expression reprogramming. While the presence of EMT is largely argued based on evidence from in vitro experiments, the in vivo data are unclear (184). Whether the progression of a noninvasive tumor into a metastatic tumor involves EMT (178, 184) needs further study. This controversy is extended by the rarity of EMT-like morphological changes in primary tumors and the observation that metastases are histologically and molecularly similar to the primary tumor. Thus, the role of EMT in tumor metastasis is difficult to assess as it is challenging to obtain tumor cells that have activated in the EMT program for or during metastasis (172).

Microarray Analysis of Heterogeneity, Clonality and Prognostic Potential

Expression profiling has revealed ‘metastasis signatures’ or poor prognosis gene signatures expressed by neoplastic cells within individual carcinomas and the potential to predict metastasis (5, 185). This has been suggested to infer that metastatic propensity might be an intrinsic property of a primary tumor that is developed relatively early in multistep tumor progression and is therefore expressed by the bulk of neoplastic cells within a tumor. It has also been proposed (76, 77) that a set of genes may mediate metastasis to specific organs, such as to the bone marrow or lungs. Studies by Urquidi et al. (9) provided direct proof that individual cancer cells coexist within a tumor, differ in metastatic capability and that metastatic primary tumors contain tumor subpopulations with variant metastatic proclivities and expression profiles. Montel et al. (186) reported that as the metastatic proclivity of a tumor increases, the cellular populations within the tumor develop increasingly variable expression profiles. They suggested, based on the concept of tumor progression (141), that the metastatic foci selected during clonal evolution represent the final stage in the development of a metastasis. However, as we have reviewed here, tumor progression is a continuum and does not end with metastasis. It continues during the growth of primary tumors and metastatic nodule(s), including the development and selection of variants resistant to chemotherapy. Tumor cells within a metastasis, at least initially, express all of the genetic alterations necessary for the metastatic process. However, as tumors progress, heterogenic tumor subpopulations develop within a metastasis, including cells with different metastatic capabilities. Gancberg et al. (187) examined pairs of primary and metastatic tumors from 100 breast cancer patients and reported that 6% had discordant Her2/neu over expression by the metastatic tissue as compared to the primary tumor. FISH analysis from 68 of the patients revealed a 7% discordance between primary and secondary lesions, but from different patients then those found by immunohistochemistry. In addition, they examined Her2/neu over expression from multiple metastatic lesions in 17 patients, revealing that 18% differed in Her2/neu expression. Suzuki and Tarin (8) also examined matched, primary breast tumors and their metastases and concluded that there were limited but statistically significant differences between the primary tumors and their lymphatic metastases. This study (8) also suggested that the genetic program for metastasis developed over time, although occasionally it occurred early during tumor progression, ultimately resulting in heterogeneity both within and between metastases.

The identification of microarray profiles with clinical relevance has supported the development of prognostic signatures for classifying tumors into risk groups and groups targeted for differential treatment approaches or no treatment. In breast cancer this approach has been undertaken by multiple investigators with dispirit results. The research strategy used a retrospective analysis of samples with follow-up, selection of discriminator genes, and the development of a predictive multigene classifier (188). A statistical analysis from the early studies suggested flaws in this experimental design (189). In retrospect two datasets are needed: one to develop the classifier (training set), and another to test the classifier (test or validation set). These two sets are obtained by splitting the original dataset, if it is large enough. Further, a validation using a third independent set is desirable. With this approach multiple genomic-prognostic classifiers for breast cancer have been developed, although the overlap of genes in these signatures has been low. Nonetheless, the primary determinants of all the signatures are proliferation, ER-status, HER2-status and, less prominently, angiogenesis, invasiveness and apoptosis. Thus, it is likely that these signatures detect the same biological processes and pathways involved in metastasis.

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs)

It has been over a century since Cohnheim (190) proposed the “embryonic theory” of cancer that postulated that human tumors arise from embryonic cells that persevere in tissues without reaching maturity. This theory has developed into the CSC hypothesis which states that cancers develop from a subset of malignant cells that possess stem cell characteristics such that tumors have rare cells with infinite growth potential (191). It is noted that this characteristic of infinite growth potential is also the definition of a tumor cell. CSCs are suggested to express characteristics of both stem cells and cancer cells, and have properties of self-renewal, asymmetric cell division, resistance to apoptosis, independent growth, tumorigenicity and metastatic potential. The CSC theory suggests that tumors include a population of asymmetrically dividing CSCs that give rise to rapidly expanding progenitor cells, which eventually differentiate and exhaust their proliferative potential. The stem cells retain their original phenotype and proliferative competence, which is referred to as “self-renewal” capacity. Cell populations enriched for CSCs are hypothesized to display increased tumorigenic potential in serial transplantation assays, as compared to the bulk of tumor cells.

The first definitive evidence of a CSC was with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by Bonnet and Dick in 1997 (192). This study used the cellular hierarchy observed for hematopoietic cells as a model to describe the development of AML from a primitive progenitor cancer cell, now known as the CSC. The tumor initiating cells were all found to have a distinct surface phenotype (CD34+/CD38−), irrespective of AML subtypes and/or the degree of heterogeneity in the tumor from which they were isolated (192). A CSC origin has now been demonstrated for a range of “liquid tumors” (193), including B and T acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL and T-ALL, respectively) and arguably with a variety of solid tumors (194).

Given the similarities between normal and CSCs it has been speculated that CSCs originate from normal self renewing stem cells that have accumulated oncogenic mutations. However, it is suggested that mutations in progenitor or differentiated cells induce dedifferentiation and self-renewal capacity (195, 196). The self-renewal capacity and multipotency of CSCs is suggested to provide a mechanism for tumor recurrence, frequently observed after surgical excision of the primary tumor, but presumably not the CSCs. As discussed above, tumors are heterogeneous such that not all tumor cells possess the same phenotype including metastatic potential. The CSC theory implies that if CSCs are the only subset of cells capable of initiating new tumor growth, then CSCs must be involved in the metastatic process. Therefore, it is posited that as a CSC possesses tumorigenic, invasive and migratory characteristics it will also have all of the necessary attributes to result in a metastasis. However, many reports on CSCs are contradictory, varying in how they should be identified, their characteristics and correlations between clinical outcome and tumor CSC status (197). These contradictory observations have made the CSC hypothesis highly contentious, including the finding that CSCs are tumor cells with metastatic properties and that the cells within the metastatic lesion may then lose the metastatic phenotype; the hypotheses are not well supported clinically. Further, it is not clear whether CSCs are “true” stem cells or represent a highly malignant cellular subpopulation. The recent publication by Morrison et al. demonstrated that by optimizing xenotransplantation procedures, one can increase the frequency of tumor-initiating human melanoma cells (198). This suggests that, at least in some human cancers, tumor-initiating cells are frequent and raised the question of whether the CSC concept applies to solid tumors. Thus, the link between CSCs and metastasis is circumstantial, based on correlations between the frequency of cells required to form a metastasis, cellular phenotypes and the expression of genes associated with “stem cells” or EMT (199). Indeed, the concept that the rare metastases-forming cells found in tumors corresponds to the equally rare CSCs, appears to represent a new nomenclature for a concept discussed in the 1970's by Fidler and co-workers. Both selected cells and CSCs have the potential to form a secondary tumor, with a similar histological architecture as tumor cells in the primary tumor (200). Further, both stem cells and metastatic cells are critically reliant on the microenvironment (“metastatic niche”) that they reside in. As Kaplan et al. have discussed such a niche is required for the formation of metastases (158), and the need to change an organ microenvironment into an appropriate niche may contribute to the latency (and potentially failure) of a disseminated tumor cell to grow into a gross metastasis (191).

Summary and Future Direction

Once a diagnosis of a primary cancer is established, the urgent question is whether it is localized or metastasized. Despite improvements in diagnosis, surgical techniques, general patient care, and local and systemic adjuvant therapies, most deaths from cancer result from metastases that are resistant to conventional therapies. The organ microenvironment, in addition to facilitating metastasis can also modify the response of metastatic tumor cells to therapy and reduce the effectiveness of anticancer agents. In addition, metastatic cells are genetically unstable with diverse karyotypes, growth rates, cell-surface properties, antigenicities, immunogenicities, marker enzymes, and sensitivity to various therapeutic agents resulting in biologic heterogeneity. The process of cancer metastasis is sequential and selective and incorporates stochastic elements. Thus, the growth of metastases represents the endpoint of many events that few tumor cells survive. Primary tumors consist of multiple subpopulations of cells with invasive and metastatic properties, with the potential to form a metastasis in a process dependent on the interplay of tumor cells with host factors. The finding that different metastases can originate from multiple progenitor cells contributes to the biological diversity and provides additional challenges to therapeutic intervention. Further, even within a solitary metastasis of clonal origin, heterogeneity can rapidly develop. Thus, it is critical to improve our understanding of metastatic cell characteristics that will allow us to target them for therapeutic intervention. Clearly, the pathogenesis of metastasis depends on multiple interactions between metastatic cells and host homeostatic mechanisms. We posit that the interruption of these interactions will inhibit or help eradicate metastasis. Clinical efforts have focused on the inhibition or destruction of tumor cells; however, strategies to treat metastatic tumor cells and modulate the host microenvironment now offer new treatment approaches. The recent advances in our understanding of the metastatic process at the cellular and molecular level provide unprecedented potential for improvement and the development of effective adjuvant therapies.

Table 2.

Metastasis Timeline

| 1829 | Jean Claude Recamier developed the term ‘metastasis’ (1). |

| 1858 | Rudolf Virchow suggested that metastatic tumor dissemination was determined by mechanical factors (18). |

| 1889 | Stephen Paget proposed the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis to explain the organs that are afflicted with disseminated cancer (17). |

| 1915 | Makoto Takahashi developed the first murine model of metastasis (204). |

| 1929 | James Ewing proposed that metastasis was determined by the anatomy of the vascular and lymphatic channels that drain the primary tumor (19). |

| 1944 | Dale Rex Coman identified the role of cellular adhesiveness to metastasis and the distribution of embolic tumor cells (205). |

| 1952 | Irving Zeidman demonstrated the transpulmonary passage of tumor cell emboli resulting in metastases on the arterial side (206). |

| 1952 | Balduin Lucke studied the organ specificity of tumor growth following intravenous injection of tumor cells and comparing growth in the liver and lung (207). |

| 1955 | Eva Kline demonstrated that cells adapted to ascites growth preexist within the parent tumor and have an increased malignant phenotype (208). |

| 1962 | Gabriel and Tatiana Gasic demonstrated that enzymatic manipulation of cell surfaces can affect metastatic potential (210). |

| 1965 | Bernard and Edwin Fisher used 51chromium-labelled tumor cells in quantitative dissemination studies (211). |

| 1966 | Bernard and Edwin Fisher distinguished lymphatic from hematogenous metastasis (209). |

| 1970 | Isaiah Fidler reported that metastasis can result from the survival of only a few tumor cells using lUdR-labeled tumor cells (22). |

| 1973 | Isaiah Fidler reported the in vivo selection of tumor cells for enhanced metastatic potential (117). |

| 1973 | Beppino Giovanella and coworkers demonstrated that human tumors can metastasize in thymic-deficient nude mice (212). |

| 1975 | Irwin Bross proposed the metastatic cascade to define a number of sequential events needed for disseminated cancer (213). |

| 1975 | Garth Nicolson proposed that the organ specificity of metastasis is determined by cell adhesion (214). |

| 1976 | Peter Nowell proposed the clonal evolution of tumor-cell population (141). |

| 1976 | Lance Liotta and Jerome Kleinerman linked invasion and metastasis to the production of proteolytic enzymes by metastatic cells (215). |

| 1977 | Isaiah Fidler and Margaret Kripke showed the metastatic heterogeneity of neoplasms (10). |

| 1980 | Lance Liotta demonstrated metastatic potential is correlated with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen (216). |

| 1980 | Ian Hart and Isaiah Fidler demonstrated the organ specificity of metastasis using ectopic organs (20). |

| 1980 | James Talmadge and collaborators demonstrated the regulatory role of NK cells in tumor metastasis (217). |

| 1981 | George Poste and Isaiah Fidler reported that interactions between clonal subpopulations could stabilize their metastatic properties, whereas a clonal subpopulation is unstable that following a short co-culture results in the emergence of metastatic variants (13). |

| 1982 | Karl Hellmann designed first anti-metastasis drug clinical trial (Razoxane) (218). |

| 1982 | James Talmadge and Sandra Wolman showed that cancer metastases are clonal and that metastases originate from a single surviving cell (149). |

| 1982 | James Talmadge and Isaiah Fidler provided direct evidence that the metastatic process was selective using spontaneous metastases from multiple metastatic variants (25). |

| 1982 | George Poste and Irving Zeidman demonstrated the rapid development of metastatic heterogeneity by clonal origin metastases (151). |

| 1982 | Garth Nicolson and Susan Custead demonstrated that metastasis is not due to adaption to a new organ environment but rather was a selective process (135). |

| 1984 | David Tarin and colleagues reported the evidence of organ-specific metastasis in ovarian carcinoma patients who were treated with peritoneovenous shunts (47). |

| 1984 | James Kozlowski and coworkers demonstrated metastatic heterogeneity of human tumors using immune incompetent mice (14). |

| 1984 | Avraham Raz and coworkers demonstrated tumor heterogeneity for motility and adhesive properties and their association with metastasis (219). |

| 1985 | Isaiah Fidler and coworkers addressed the critical role of macrophages in the process of metastasis (220). |

| 1986 | Leonard Weiss and coworkers identified the concept of metastatic inefficiency (221). |

| 1988 | Patricia Steeg and collaborators identified the first metastasis suppressor gene (222). |

| 1990 | Richard Wahl and coworkers demonstrated the ability of FDG to detect LN metastases with PET scans (223). |

| 1990 | Lloyd Culp and collaborators documented the utility of bacterial LacZ as a marker to detect micrometastases during tumor progression (224). |

| 1991 | Judah Folkman and coworkers demonstrated a relationship between metastasis and angiogenesis in patients with breast cancer (225). |

| 1992 | Jo Van Damme reported the role of chemokines in tumor-associated macrophage facilitation of metastasis (226). |

| 1994 | Judah Folkman demonstrated that the removal of a malignant primary tumor in mice spurs the growth of remote tumors, or metastases (227). |

| 1997 | Robert Hoffman and the visualization of tumor cell invasion and metastasis using GFP expression (228). |

| 2000 | David Botstein demonstrated diversity in the gene expression patterns by breast cancer tissues (229). |

| 2001 | Irving Weissman and coworkers suggested the role of cancer stem cells in metastasis (230). |

| 2002 | Rene Bernards and Robert Weinberg proposed that metastatic potential is determined early in tumorigenesis, explaining the apparent metastatic molecular signature by most cells in a primary tumor (231). |

| 2002 | Jean Paul Thiery and Robert Weinberg proposed that EMT could explain metastatic progression (172,231). |

| 2002 | Christopher Klein and collaborators reported the genetic heterogeneity of single disseminated tumors cells in minimal residual cancer (232). |

| 2002 | Laura Van 't Veer and co-workers reported that a specific gene expression profile of primary breast cancers was associated with the development of metastasis and a poor clinical outcome (185). |

| 2003 | Yibin Kang and colleagues identified a molecular signature associated with metastasis of breast tumors to bone (233). |

| 2003 | Michael Clarke and Max Wicha suggest that the ability of breast cancer tumors to metastasize resides in just a few “breast cancer stem cells” that are highly resistant to chemotherapy (234). |

| 2006 | Kent Hunter emphasized the role of genetic susceptibility for metastatic (235). |

| 2007 | Li Ma and Robert Weinberg identified the first metastasis-promoting micro-RNA (236) |

| 2008 | William Harbour and coworkers demonstrated that micro-RNA expression patterns could predict metastatic risk (237). |

| 2008 | Joan Massagué and co-workers reported that micro-RNAs can suppress metastases (238). |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jill Hallgren, Alice Cole, and Lola López for their expert assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Grant support: Nebraska Research Initiative Grant “Translation of Biotechnology into the Clinic”(JET), Avon-National Cancer Institute Patient Award CA036727 (JET), Cancer Center Support Core Grant CA16672 and Grant 1U54CA143837 (IJF) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interests

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Recamier JC. Recherches sur la Traitment du Cancer sur la Compression Methodique Simple ou Combinee et sure l'Histoire Generale de la Meme Maladie. 2 ed. 1829.

- 2.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:453–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorland WA. Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. 24 ed. Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Monte U. Does the cell number 10(9) still really fit one gram of tumor tissue? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:505–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weigelt B, Glas AM, Wessels LF, et al. Gene expression profiles of primary breast tumors maintained in distant metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15901–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634067100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, Golub TR. A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2003;33:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]