Abstract

Hand eczema is often a chronic, multifactorial disease. It is usually related to occupational or routine household activities. Exact etiology of the disease is difficult to determine. It may become severe enough and disabling to many of patients in course of time. An estimated 2-10% of population is likely to develop hand eczema at some point of time during life. It appears to be the most common occupational skin disease, comprising 9-35% of all occupational diseases and up to 80% or more of all occupational contact dermatitis. So, it becomes important to find the exact etiology and classification of the disease and to use the appropriate preventive and treatment measures. Despite its importance in the dermatological practice, very few Indian studies have been done till date to investigate the epidemiological trends, etiology, and treatment options for hand eczema. In this review, we tried to find the etiology, epidemiology, and available treatment modalities for chronic hand eczema patients.

Keywords: Etiology, hand eczema, review

Introduction

What was known?

Hand eczema is a common, chronic occupational disease.

Its etiology is difficult to determine in most of the cases and treatment is challenging to dermatologist.

Hand eczema is a very common and widespread condition, which was presumably first described in the 19th century.[1] It is a frequently encountered problem, affecting individuals of various occupations. Variety of factors may take part in the causation of this condition including endogenous and external/environmental factors acting either singly or in combination. In the 19th century, dermatologists described several morphological variants of hand eczema such as eczema solare, rubrum, impetiginoides, squamosum, papulosum, and marginatum.[2]

The exact prevalence of hand eczema is difficult to determine because it is not a reportable disease and many who are affected do not seek medical attention. An estimated 2-10% of population is likely to develop hand eczema at some point of time during life. In addition, 20-35% of all dermatitis affects the hands. It appears to be the most common occupational skin disease, comprising 9-35% of all occupational disease and up to 80% or more of all occupational contact dermatitides.[3] Females are more commonly involved than males (2:1), possibly because of increased exposure to wet work and household chemicals.[4] Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) was found to be a cause of hand eczema in half of the cases, whereas allergic contact dermatitis comprised 15% cases.[5] Due to the high incidence and prevalence of this pathology, it has enormous socioeconomic consequences and a massive impact on patients’ quality of life. The increasingly complex and industrialized environment of the 21st century, has made it all the more important to find the exact etiology of the disease and to use appropriate preventive and treatment measures.

Various morphological forms of hand eczema are seen, which differ only clinically rather than histologically. Knowledge of pattern of contact sensitivity in patients of hand eczema may give insight of various etiological agents responsible for it, which can further help in management of these patients. The management of hand eczema depends on its cause, while allergic or irritant contact dermatitis of the hands can usually be elucidated by proper history taking and patch test, endogenous hand eczema is often diagnosed after exclusion of the former conditions.

Definition

The word “eczema” has an obscure origin. It was first used by Aetius Amidenus, physician to the Byzantine court in the sixth century. A current and acceptable definition of eczema is that it is “an inflammatory skin reaction characterized histologically by spongiosis with varying degrees of acanthosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.” The clinical features of eczema may include itching, redness, scaling, clustered papulovesicles, hyperkeratosis, or fissuring. The condition may be induced by a wide range of external and internal factors acting singly or in combination. Dermatitis means nothing more than inflammation of the skin. There is no universal agreement on the use of these two terms and they are the cause for some confusion. Dermatitis has a broader application, in that it embraces all forms of inflammation of the skin.

A clear and worldwide-accepted definition of what is included, as “Hand Eczema” does not exist. After having excluded the disorders of known etiology (e.g., Tinea mannum, scabies), well-defined noneczematous disorders (e.g., psoriasis, lichen planus, granuloma annulare, porphyria cutanea tarda, keratosis palmo-plantaris, fixed drug eruptions), and neoplastic disorders from the category of hand dermatoses, and if hands are not involved as part of an extensive skin disorder, diagnosis of characteristic cases of hand eczema present little difficulty. The term hand eczema[6] implies “the dermatitis which is largely confined to the hands, with none or only minor involvement of other areas.”

Epidemiology

Prevalence of hand eczema varies according to the geographical region. In a Swedish epidemiological study[7] of 20,000 individuals between ages 20 and 65, the prevalence of hand eczema occasionally during the last year was found to be 11%. All forms of eczema and contact dermatitis accounted for 10-24% of the patients (1978-1981) seen in eight hospital centers in Great Britain.[8] It is likely that at least 20-25% of these had eczema confined to the hands. In an analysis of 4825 patients patch tested in eight European Centers, the International Contacts Dermatitis Research group found that the hands alone were involved in 36% of males and 30% of females.[9] Agrup, with the use of questionnaire survey followed by examination, estimated the prevalence of hand eczema to be 1.2% in southern Sweden.[10]

The incidence of hand eczema was found to be 10.9-15.8% in various studies[11] while in Indian dermatologic outpatient department of 5-10% of allergic contact dermatitis patients, hand involvement was seen in two-third of cases.[12,13]

In a large study conducted by Meding[14] in Sweden, which included a cohort of about 20,000 people, 11.8% of responders reported having hand eczema on some occasion in the previous 12 months. Hand eczema was found to be almost twice as common in females as in males, with a ratio of 1.9, and was most common in young females. The latter observation has also been noted in other prevalence studies.

The most common cause of hand eczema is contact irritants. In Meding's study, the most common type of hand eczema were irritant dermatitis (35%), atopic hand eczema (22%), and allergic contact dermatitis (19%). The corresponding females:males ratios were 2.6:1, 1.9:1, 5.4:1, respectively. The most frequent positive patch test was for Nickel and Cobalt. A total of 32% of the patients had one or more positive reactions to the standard series. Similar results have been found in other publications on the patch test results. When the different occupational groups are compared, the only statistically significant increase in prevalence of a contact allergy was noted among women in administrative work for colophony. Whether this is attributable to exposure to resin in paper is not known.

History of childhood eczema, female sex, occupational exposure, atopic mucous membrane symptoms (rhinitis or asthma), and a service occupation are established important risk factors.[15] Poor prognostic factors for hand eczema are wide-spread hand involvement, younger age of onset, history of childhood eczema, and contact allergy.

Pathogenesis

Irritant contact dermatitis

Irritant contact dermatitis is a condition caused by direct injury of the skin. An irritant is any agent capable of producing cell damage in any individual if applied for sufficient time and in sufficient concentration.

Immunologic processes are not involved, and dermatitis occurs without prior sensitization. Irritants cause damage by breaking or removing the protective layers of the upper epidermis. They denature keratin, remove lipids, and alter the water-holding capacity of the skin. This leads to damage of the underlying living cells of the epidermis.

The severity of dermatitis produced by an irritant depends on the type of exposure, vehicle, and individual propensity. Normal, dry, or thick skin is more resistant to irritant effects than moist, macerated, or thin skin. Cumulative irritant dermatitis most commonly affects thin exposed skin, such as the back of the hands, the webspaces of the fingers.

There is difference between the mechanism of acute and chronic irritant contact dermatitis. Chronic irritant contact dermatitis is due to disturbed barrier function and increased epidermal cell turn over while acute ICD is a type of inflammatory reaction. Mediators involved in this type of reactions are TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, IL-2, and granulocyte monocyte-colony stimulatory factor.[16]

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction only affecting previously sensitized individuals. A common example of allergic contact dermatitis is the allergic reaction to plants, such as poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Contact allergens are invariably smaller than 500 D, thus penetrate deeper skin and after being conjugated with autologous proteins, sensitization takes place. Two distinct phases in a type IV hypersensitivity reaction are the induction (i.e., sensitization) phase and the elicitation phase.

During the induction phase, an allergen, or hapten, penetrates the epidermis, where it is picked up and processed by an antigen-presenting cell. Most allergens in contact dermatitis are of low molecular weight and require minimal processing. However, many have a complicated structure and are significantly altered by the antigen-presenting cells. Antigen-presenting cells include Langerhans cells, dermal dendrocytes, and macrophages. The processed antigen is presented to T-lymphocytes, which undergo blastogenesis in the regional lymph nodes. One subset of these T cells differentiates into memory cells, whereas others become effector T lymphocytes that are released into the blood stream.

The elicitation phase occurs when the sensitized individual is again exposed to the antigen. Serial biopsies during the first 24 hours after dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) challenge in 15 sensitized patients[17] have shown that DNCB penetrates the epidermis very rapidly and associates with epidermal cells, both keratinocytes and Langerhans cells (LCs), within 1 hour of application and localizes in the sweat glands and deep levels of the pilosebaceous follicles by 3 hours, and at 6 hours large dendritic DNCB-positive cells appear in the papillary and reticular dermis, particularly around these appendages. Within 24 hours of antigen application, LCs migrate to regional lymph nodes where they present the antigen to the compatible T-lymphocytes within the lymph nodes. Certain T-lymphocytes like CD4+ and CD45 RA+ become physically apposed to the LCs, thus facilitating the transfer of antigen. The processed antigen is presented to the circulating effector T-lymphocytes that, in turn, produce lymphokines. Many mediators or cytokines are released namely, IL-1 by antigen-presenting cells and IL-2 by T-lymphocytes. The cytokines cause clonal proliferation of antigen-specific T-helper 1, CD4+ lymphocytes which might be capable of responding to a particular antigen when future exposure occurs. The elicitation phase requires several hours to develop, and, as a result, symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis usually develop hours to days following exposure. Once acquired, contact sensitivity tends to persist. The degree of sensitivity may decline unless boosted by repeated exposure, but with a high initial level of sensitivity, it may remain demonstrable throughout life.

Role of skin barrier and genetics

There are multiple components in epidermis which are important to barrier function. These components are claudin, desmoglein, filaggrin, ceramide, proper control of proteases, and various scaffolding proteins (involucrin, envoplakin, and periplakin). When functioning properly, this layer is an efficient barrier to epidermal invasion of allergens and bacteria and also prevents water loss. The first line of defense within the epidermal barrier is the stratum corneum, which serves several fundamental roles in maintaining protection from the environment as well as preventing water loss. The stratum corneum consists of a multicellular vertically stacked layer of cells embedded within a hydrophobic extracellular matrix. This extracellular matrix is derived from the secretion of lipid precursors and lipid hydrolases. These hydrolases cleave the precursors to form essential and nonessential fatty acids, cholesterol, and at least 10 different ceramides, which self-organize into multilayered lamellar bilayers between the corneocytes and form a watertight “mortar” maintaining skin hydration.[18] Corneocytes in the stratum corneum are held together by tight junctions and various scaffolding proteins which help in maintaining skin barrier. Claudins are a family of proteins that are important components of the tight junctions between corneocytes. Claudin-deficient patients have aberrant formation of tight junctions causing disruption of the skin barrier. Claudins help in preventing moisture loss through this layer of the skin. This tight junction also blocks access through the skin to various external environmental allergens. Thus, claudin may help in prevention of immune exposure to allergic stimuli. Scaffolding proteins are required for effective epidermal barrier. Loss of epidermal scaffolding proteins such as involucrin, envoplakin, and periplakin is associated with alterations in epidermal barrier function and altered formation of cornified epidermal envelope.[19]

Another factor which is required for normal functioning of the epidermis is proper control of skin proteases activity. SPINK is a protein that inhibits serine protease action in the skin. The SPINK gene is absent in Netherton's syndrome. In this syndrome, the patient has severe atopic dermatitis, scaling, and raised serum IgE level. Lack of SPINK results in uncontrolled serine protease elastase-2 activity. Increased protease activity negatively alters filaggrin and lipid (ceramide) processing thereby decreasing skin barrier function.

Filaggrin is an important protein found in lamellar bodies of stratum granulosum corneocytes. When these granules are released they become a vital component of the extracellular matrix of the stratum corneum. The filaggrin gene resides on human chromosome 1q21 within the epidermal differentiation complex, a region that also harbors genes for several other proteins that are important for the normal epidermal barrier function.[20] Filaggrin normally assists in cytoskeletal aggregation and formation of the cornified epidermal envelope. It is required for normal lamellar body formation and content secretion. Furthermore, as corneocytes mature and start losing water, filaggrin dissociates from the cornified envelope and is processed into acidic metabolites and acting as osmolytes help to maintain hydration. These acidic metabolites also keep the pH below the threshold required for the activation of Th2-inducing endogenous serine proteases which has important role in pathogenesis of atopic hand eczema. Therefore, a filaggrin mutation contributes to a disrupted epidermal barrier, increased water loss, inflammation and exposure to environmental allergens resulting in atopic hand eczema.[21]

An impaired expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as cathelicidin and defensins was detected in lesional skin in patients with atopic dermatitis.[22]

Detergents cause stratum corneum damage by removal of the surface lipid layer and increase TEWL leading to irritant contact dermatitis.[23]

Stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme (SCCE) is a serine protease, which has a role in the desquamation of skin via the proteolysis of desmosomes in the stratum corneum. An elevated expression of hK7 (human tissue kallikrein 7) or SCCE in the epidermis leads to increased proteolytic activity, pathological desquamation, and inflammation in many skin diseases such as Netherton syndrome, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis.[24,25,26]

Etiology

Most cases of hand eczema have a multifactorial etiology which can be broadly divided into two groups: Exogenous and endogenous causes. Among exogenous causes contact irritants are mostly commonly blamed for hand eczema. These include soaps, detergents, rubber, vegetables, etc., Physical friction and minor trauma can also cause irritant contact dermatitis.

Ingested allergens like nickel, chromium, and drugs used topically like neomycin and hydroxyquinolones are other factors responsible for hand eczema. Dermatophytide reaction to tinea pedis can also involve hands. Certain occupations are particularly likely to provoke hand eczema like hairdressers, farmers, construction workers, dental and medical personnel, metal workers, food handlers, etc.

Among endogenous causes, atopy is the most common cause of hand eczema. Role of stress, hormones, and xerosis is also documented. Some cases are idiopathic.

Bajaj et al.[27] reported patch-test data from a single general dermatology center in North India. Out of the 1000 patients analyzed, positive reactions were seen in 590 (59%) patients. Positivity to nickel (11.1%) neomycin (7%), mercaptobenzthiazole (6.6%), nitrofurazone (6%), colophony (5.7%), fragrance mix (5.5%), and cobalt chloride (5.4%) antigens was seen. However, parthenium was the most common allergen based on the proportion of patients tested with it (14.5%). In men, potassium dichromate (30%) was the most common sensitizer and in women, and nickel (43%) was the most common to show patch test positivity.

In a study of patch testing in hand eczema by Kishore et al.[28] the positive patch test was seen in 82% of the patients which was high compared with other studies. Potassium dichromate was the most common sensitizer testing positive in 26% of the patients while nickel was the next common testing positive in 18% of the patients. The high positivity for potassium dichromate was explained by its presence in detergents and cements.

A study by Kaur and Sharma[29] in Chandigarh found that 53.1% of the patients with hand eczema were sensitive to metals. Of these, nickel, cobalt and chromate sensitivity was seen in 40.6, 31.2 and 21.8% patients respectively. In the same study, medicaments, rubber, and vegetable sensitivity was found in 40.6, 13, and 13% patients respectively. The miscellaneous sensitizers were positive in 23.4% patients with hand dermatitis; they included plants, oil, file cover, currency notes, DDT, paraphenylene diamine, formaldehyde, mercuric chloride, film, and paper developer.

Soaps and detergents were found to be the second most common sensitizers in females in a study of 71 patients by Bajaj.[30] These findings were also observed in another study undertaken by Singh and Singh[31] who were of the opinion that detergents are responsible for causing both irritant and allergic contact dermatitis.

Vegetables are a common cause of contact dermatitis of hands in housewives and cooks. It occurs as scaling and fissuring of palmar surface of index, middle finger, and thumbs. The most common sensitizers are garlic (Allium sativum), onion (Allium cepa), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), carrot (Daucus carota), lady finger (Hibiscus esculentes), and ginger (Zanzibar officinale).

A study by Pasricha and Kanwar[32] reported vegetable sensitivity to be as high as 75.8% and 82.7% in housewives eczema respectively. Garlic and onion were the most frequent sensitizers. This study also showed that allergic contact dermatitis to garlic and onion has predominant involvement of index, thumb, and middle finger of dominant hand and thumb of the other hand (fingertip dermatitis).

Dermatitis on finger called “tulip finger” is seen in gardeners and bulb growers.[33] Most growers had contact with Narcissus sap during the investigation. Contacts with other irritants such as hyacinth dust and pesticides seemed to be also responsible. Patch tests showed that contact sensitization exists to pesticides and to flower-bulb extracts.

Wet work is a major external risk factor for hand dermatitis. In a study of female cleaners,[34] it was found that they had wet hands more than a quarter of the working day. Water as such decreases the protective capacity of the skin and occlusion further increases irritant effect. In many wet work occupations, lipid soluble chemicals are added to water to achieve the cleaning effect. In the skin this effect is unfavorable because intracellular lipids are washed away. These lipids are important factors in cutaneous protective capacity. The removal of lipid induces structural and physiochemical alterations in the skin, which apparently facilitates the process of cutaneous irritation.

There are various endogenous factors of hand eczema-idiopathic (as in hyperkeratotic palmar dermatitis) and atopy; stress and excessive sweating may aggravate this condition. Atopy has been considered the most common cause of hand eczema[35] and the most frequently involved parts of body are the hands. The worst prognosis was seen in patients of atopic hand dermatitis, as well as it was associated with a longer duration, high continuity of symptoms, and extensive involvement.[36]

In a study of 777 patients of atopic dermatitis,[37] hand involvement was present in 58.9% of patients. The hand involvement presented unique physical, social, and therapeutic challenges for the atopic patients. It was found that involvement of dorsal hand surfaces and the volar wrist may suggest atopy as a cause of hand eczema.

Clinical patterns of hand eczema

There are different patterns of hand eczema which differ only clinically, not histologically. Several clinical variants of hand dermatitis have been described, including hyperkeratotic (i.e., psoriasiform or tylotic), frictional, nummular, atopic, pompholyx (i.e., dyshidrosis), and chronic vesicular hand dermatitis. Hybrids of these patterns exist and some experts do not agree on classifications.[38]

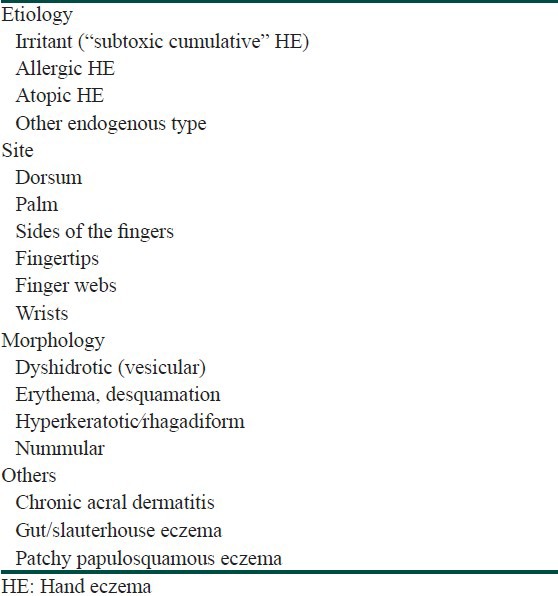

Many published classifications[39,40,41] involve a combination of etiological factors (irritant, allergic, and atopic disease) and morphological features (pompholyx, vesicular, and hyperkeratotoic eczema, Table 1). However, no single classification of hand eczema is satisfactory.

Table 1.

Classification of hand eczema (HE). Overlapping disease entities and multifactorial etiologies are common

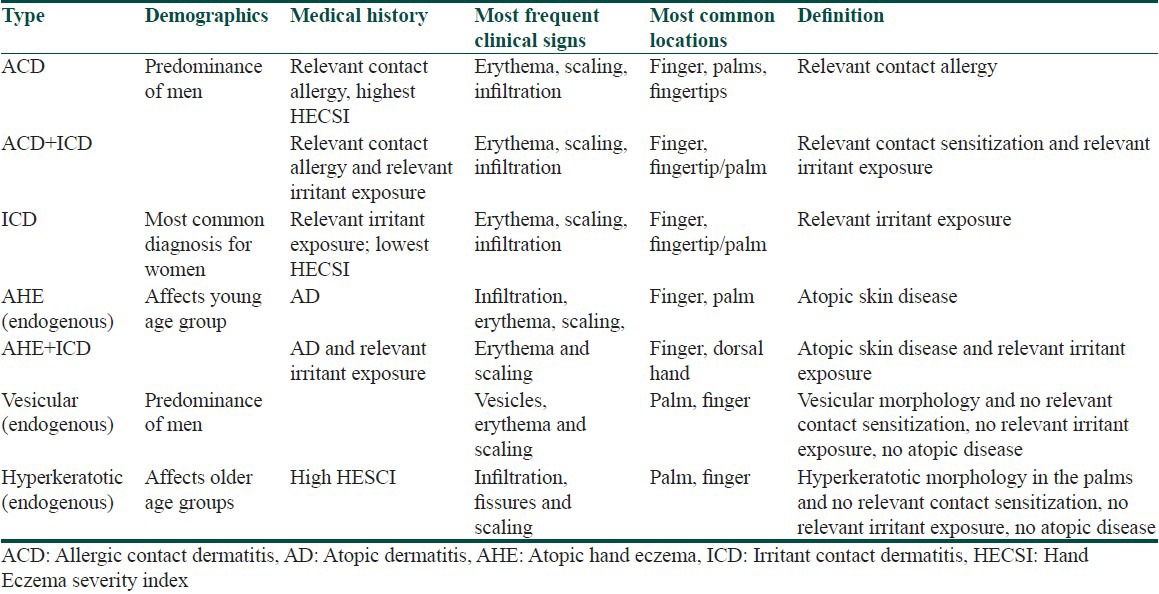

Other classification system based on an analysis of patients attending European patch testing centers was recently proposed.[41] In total, 416 patients from the 10 participating clinics were included in the study. It includes seven subgroups according to demographics, medical history, and lesions’ morphology [Table 2].

Table 2.

Proposed classification of hand eczema[41]

Different clinical patterns of hand eczema included in this review

Pompholyx (vesicular eczema of palms and soles), dyshidrotic eczema

Patchy vesiculosquamous eczema

Hyperkeratotic palmar eczema (tylotic eczema)

Recurrent focal palmar peeling

Discoid eczema (nummular eczema)

Wear and tear dermatitis (housewives dermatitis)

Ring eczema

Finger tip eczema

Apron eczema

Gut/slaughterhouse eczema

Chronic acral dermatitis.

Clinically, hand eczema is characterized by signs of erythema, vesicles, papules, scaling, fissures, hyperkeratosis, and symptoms of itch and pain. Chronic hand eczema is considered when hand eczema is of more than 6 months duration.

Histopathologically all patterns show similar changes. Epidermis shows spongiosis, acanthosis, parakeratosis, infiltration by lymphocytes while dermis show vascular dilatation and lymphocytic infiltration.

Pompholyx

Pompholyx (vesicular eczema of palms and soles, dyshidrotic eczema) is a frequent deep-seated vesicular eruption of idiopathic⁄unknown origin affecting the palms and soles recognized as palmoplantar pompholyx.[36] It accounts for about 5-20% of all cases of hand eczema.[10,30] When pompholyx occurs on the palms, it is named as cheiropompholyx, and when on the soles, podopomphoylx. The condition is more common in hot weather. So it is termed dyshidrotic eczema. The role of sweat glands is disputed, although distribution of lesions corresponds to emotionally activated palmoplantar sweating and hot weather. However, hyperhidrosis is not a constant feature. Role of atopy may be significant.

Lodi et al.[42] found personal and family history of atopy in 50% of their patients compared to 12% controls in study of a group of 104 patients. Nickel sulfate was the allergen with the highest positivity on patch testing: 20.19% versus 6.25% of the control group. In this study it was also observed that different haptens or antigens can produce the same clinical and histological picture of pompholyx in predisposed subjects. Aspirin ingestion, oral contraceptives, and regular smoking increase the risk of pompholyx.

Patchy vesiculosquamous eczema

This pattern is characterized by a mixture of irregular patchy, vesiculosquamous lesions occuring on both hands, usually asymmetrically.

Hyperkeratotic palmar eczema (tylotic eczema)

This condition is characterized by highly irritable, scaly, fissured, hyperkeratotic, patches on the palms, and palmar surfaces of the fingers. It is usually seen in men of middle age. A patch test is negative but found positive in 130 out of 230 patients in an Indian study.[43]

Recurrent focal palmar peeling (desquamation en aires)

This condition is a mild form of pompholyx characterized by small areas of superficial white desquamation which develop on the sides of the fingers and on the palms. The condition is relatively asymptomatic. There are usually no vesicles, but some patients may subsequently develop true pompholyx.

Discoid eczema (nummular eczema)

Discoid eczema is characterized by plaques of nonspecific morphological features, namely circular or oval plaques of eczema with a clearly demarcated edge. Discoid eczema is etiologically related to atopy, infection, physical or chemical trauma, allergy, dry skin, stress, and to drugs like methyldopa and gold. The diagnostic lesion of discoid eczema is a coin-shaped plaque of closely set, thin-walled vesicles on an erythematous base. This arises from the confluence of tiny papules and papulovesicles. Discoid eczema of hands affects the dorsa of the hands or the backside of fingers.

Wear and tear dermatitis/housewives dermatitis/dermatitis palmaris sicca/Frictional dermatitis

This condition affects housewives and cleaners who frequently immerse their hands in water and detergents. This pattern is characterized by dry skin with superficial cracks, which stands out white against an erythmatous background. Skin over the dorsa of the knuckle joints may be dry and chapped.

Ring eczema

This characteristic pattern particularly affects young women, soon after marriage; rarely men are affected. This condition is characterized by a patch of eczema which develops under a ring and spreads to involve the adjacent side of the middle finger and the adjacent area of the palm. Patch is irritable. There is usually no contact sensitivity to gold, copper, or other alloys. Less frequently, allergic contact dermatitis under rings has been observed, from nickel, gold, and palladium.[44] This type of hand eczema is probably due to accumulation of soap and detergent beneath rings, but friction may also play a role. Repeated fragrance contact on irritated skin in a semioccluded area under the rings may facilitate sensitization to cosmetic use as reported in a 16-year-old girl.[45]

Finger tip eczema

This is known as “pulpite” in France, a term that accurately localizes it to the pulps rather than the backs of the fingers. These become dry and glazed “parchment pulps,” then crack and even fissure and are extremely painful. Usually it remains localized but may occasionally extend. Two patterns are recognized. The first and the most common pattern involves most of all of the fingers, mainly those of the dominant hand particularly thumb and forefinger. This pattern is worse in the winter. In this pattern patch tests are negative or not relevant. It is a cumulative irritant dermatitis in which degreasing agents combine with trauma as causative factors. The second pattern involves preferably the thumb, forefinger, and third finger of the dominant hand. This is usually occupational. Patch tests may be rewarding in these cases. It may be either irritant (e.g., in newspaper-delivery employees) or allergic (e.g., colophony in polish or to tulip bulbs). There may be allergy to onions, garlic, or other kitchen products.

Apron eczema

The word “apron eczema” was given by Calnan.[46] Apron eczema is a type of hand eczema that involves the proximal palmar aspect of two or more adjacent fingers and the contiguous palmar skin over the metacarpophalangeal joints, thus resembling an apron. Rarely, it is caused by contact allergens, but may reflect the effect of irritants. It is more common in women and is largely endogenous in origin.[47]

Gut/slaughterhouse eczema

It is seen as a transient vesicular eczema which begins from the webs of the fingers and spreads to the sides. Each episode may be mild and may clear spontaneously but recurs at regular intervals. This specifically affects workers engaged in evisceration of carcasses of animals in slaughterhouses.[48] Pathogenesis is uncertain.

Chronic acral dermatitis

Chronic acral dermatitis is a distinctive syndrome affecting middle-aged patients and is characterized by pruritic, hyperkeratotic papulovesicular eczema of the hands and the feet.[49] It is associated with grossly elevated immunoglobulin (Ig) E levels without any personal or family history of atopy.

Contact urticaria syndrome and hand eczema

“Contact urticaria syndrome” (CUS) or “protein contact dermatitis,” first defined as a biologic entity in 1975, comprises a heterogeneous group of transient inflammatory reactions appearing within minutes to hours after contact with the eliciting substance.[50] This reaction usually occurs on normal or eczematous skin and usually disappears within a few hours. Contact urticaria (CU) in association with hand eczema is a relatively new entity, the first few cases being reported just over 20 years ago. Usually, it is the immunologic variety of CU that is associated with hand eczema. Since its recognition in the 1970, an increasing number of reports of contact urticaria in association with hand eczema have been published, to diverse substances, including various foods, animal and plant products, medicaments, and industrial chemicals. At the weakest end, patients may experience itching, tingling, or burning accompanied by erythema (wheal and flare). At the more extreme end of the spectrum, extracutaneous symptoms may accompany the local urticarial response, ranging from rhinoconjunctivitis to anaphylactic shock. The typical primary lesion (erythema, or wheal and flare) with or without secondary organ involvement resolves in hours, but atypical recurrent episodes via unknown mechanisms, convert into dermatitis (eczema).

Diagnosis of hand eczema

Though the diagnosis of hand eczema is self-evident, many times it is difficult to differentiate it from some other dermatological disorders like psoriasis, tinea mannum, lichen planus, pityriasis rubra pilaris, palmar pustulosis.

Diagnosis of hand dermatitis needs detailed history including general medical status, onset, progression and remission of dermatitis, work/job history, other exposures, family history and clinical examination. The important investigations for confirmation of allergic contact dermatitis include standard patch testing, total and differential leucocyte count evidencing eosinophilia, serum IgE level, skin biopsy, prick test, potassium hydroxide preparation, fungal and bacterial cultures, Gram staining, radioallergosorbent test (RAST), and in vitro lymphocyte stimulation test.

Standard patch test

The patch test was first used by Josly Jadassohn in 1896. He established the role of the patch test by his success in reproducing the clinical lecture of contact dermatitis from iodoform mercury salts. The test is based on the principle that whole skin of an allergic individual is capable of reacting with the causative antigen. Therefore, a standard concentration of the antigen applied on normal looking skin would also produce the same pathophysiological change, as found in allergic contact dermatitis. In cases of allergic contact dermatitis allergens is applied on a patch of the filter paper placed on an impermeable sheet/aluminum cup fixed to the skin over the back by adhesive tape. However, the Finn chambers are the most common system to apply allergens and consist of small aluminum disks, mounted on acrylic based adhesive, non-occlusive, hypoallergenic tape. The major disadvantage of this system is reaction of metal salts like mercury, cobalt, and nickel with aluminum.

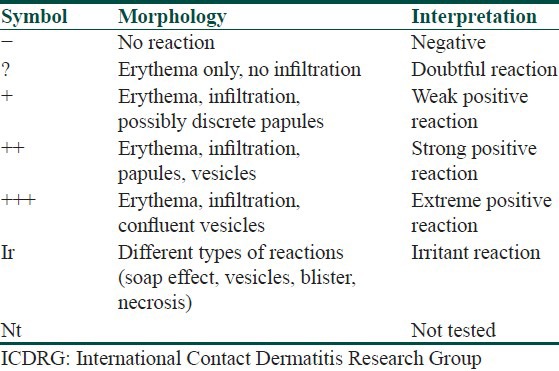

The skin area selected for the patch test should be shaved of coarse hair before application. The allergen is left in contact with skin for about 48 hours and then removed to see the degree of local inflammatory reaction. After an hour of removing the patches, the test reactions are graded as in Table 3. The patch test reading should also be taken at 96 hours.[51]

Table 3.

Scoring of the patch test according to ICDRG recommendations

Photopatch test

Some substances are photosensitizers in that these will result in dermatitis only if the skin after contact with the substances is exposed to sunlight or some other equivalent source of light emitting UVA radiation (usual doses of 5-15 J/cm2). Such substances are to be tested by the photopatch test.

TRUE test (thin-layer rapid-use epicutaneous test)

It is a new type of test system in which an allergen gel is incorporated on a polyester sheet which is then dried and cut into 9 mm × 9 mm squares. It was introduced by Fischer and Malbach.[52] These test patches are mounted on an acrylic tape covered with a siliconized protection sheet and packed in air tight, light impermeable envelopes. Ready-to-apply polyester patches coated with allergens in the hydrophilic gel are used and they have the advantage of exact dosage, thin surface spread, equal distribution, and high bioavailability of the allergen. The TRUE test patches are arranged in two panels of 12 allergens on a test strip. These are ready to apply patches and after application; they can be removed after 48 hours by physician. The patients should be asked to wait for half an hour for accurate reading. The patches should be stored between 2°C and 8°C temperature.

Advantages of the TRUE test

It is easy, convenient, and ready to use

Exact and lower dosage, thin surface spread, and equal distribution

Better tape adhesiveness

Less chances of confusion and mistakes as it is a readymade preparation.

Disadvantage of the TRUE test

More chances of washing away with sweating because of hydrophilic material

Expensive

Important steroid antigens are not included

Suboptimal sensitivity for fragrance mix antigen.

There are other ready-to-use patch tests, namely Accupatch (Smart Practice) and Epiquick (Smart Practice).[53]

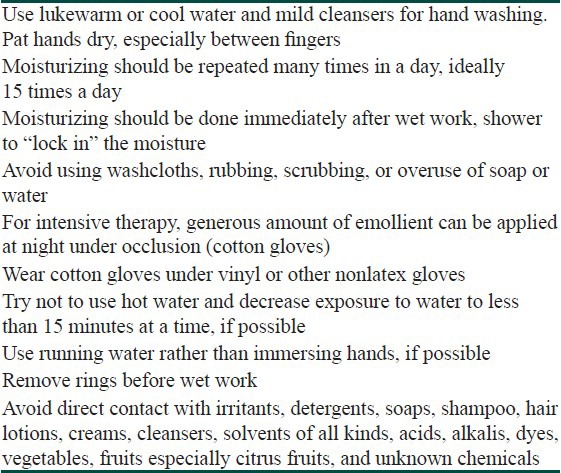

Treatment

Hand eczema has chronic relapsing and remitting course, it is challenging to the patients as well as to a dermatologist. It is estimated that 5-7% of patients with hand eczema are characterized by having chronic or severe symptoms and 2-4% of severe cases are refractory to traditional topical therapy.[41] Avoidance of allergens and irritants is the useful step of treatment but it is not possible most of the times because of the widespread occurrence of contact allergens in household substances as well as in occupational environment mostly after rapidly increasing industrialization in last 60 years. An inimitable feature in most of the cases is altered barrier function after disruption of stratum corneum, thus causing transepidermal water loss. Nearly all forms of hand eczema begin with disruption of stratum corneum barrier.[54] Thus initial management usually aims at maintenance and restoration of the barrier and controlling the inflammation. Most of the times, it would be beneficial to take symptomatic treatment to alleviate the signs and symptoms of the disease and to follow some of the important precautions in day-to-day activities. But it is found impractical to apply emollients many times as outlined below, so it is recommended to apply emollient properly overnight. In a review of therapeutic options in hand eczema, Warshaw outlined the useful guidelines for prevention and lifestyle modification in day to day activities.[38] The modified guidelines are enlisted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Prevention and lifestyle management in hand eczema patients

The management of patients with chronic hand eczema is often unsatisfactory. Although a lot of treatment options exist, there is no consensus over the choice of treatment according to duration or type of the eczema. Conventionally patients with hand eczema are treated with topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, emollients, and short course of systemic corticosteroids according to the severity of disease. Topical steroids are usually the first line agents to control the inflammation. Various types of topical corticosteroids like desonide, mometasone furoate, clobetasol propionate, betamethasone dipropionate, etc., have been used for treatment of hand eczema. Topical steroids are fast acting and control the disease in most of the patients but their use is limited by adverse effects like skin atrophy and telangiectasia. Other problems with their use are rebound flare ups, tachyphylaxis on regular use, weakening of skin barrier, and lack of efficacy in severely affected patients. It has been noted that long-term use of topical steroid can enhance the production of stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme which impairs the epidermal barrier function.[39] Short course of systemic steroids is required in the case of severe disease. But adverse effects profile of systemic steroids limits long-term use. So, it is necessary to come up with a steroid sparing agent which provides good response in the acute stage of the disease, and has less rate of recurrence. Various immunosuppressants have been investigated for use in chronic hand eczema. Different treatment modalities are enlisted in Table 5.

Table 5.

Different treatment modalities for hand eczema

Granlund[80] investigated the effect of oral cyclosporine on disease activity. Forty-one patients were enrolled to take part in this randomized parallel group design study with partial crossover in the second phase. Seventeen patients received oral cyclosporine (3 mg/kg/day) and placebo cream for 6 weeks. The other group underwent topical treatment with betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream and placebo capsules. After 6 weeks there was a crossover of those patients who did not respond to treatment in the first 6 weeks. Third phase consisted of the follow-up period of 24 weeks without intervention. There was improvement in both of the groups, but no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of participant and doctor rated good/excellent control and severity scoring.

Egan[81] reported use of low-dose oral methotrexate in five patients with recalcitrant palmoplantar pompholyx. The patients did not respond to conventional therapy and showed significant improvement or clearing after addition of methotrexate to their treatment.

In an open label study, Mittal et al.[98] used methotrexate 10-15 mg weekly in single or divided doses for 12 weeks in 15 patients of recalcitrant eczema (patients with pompholyx, n = 6), and found that two patients of pompholyx had excellent response (almost complete remission) and one patient of pompholyx had good response (partial remission). The main effect of methotrexate is on epidermal proliferation by its metabolite polyglutamate causing adenosine release.[99] On binding with adenosine receptors, adenosine inhibits lymphocyte proliferation as well as proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and increases production of IL-1 receptor antagonist in monocyte.

A single case report described a patient with a 4-year history of recurrent dyshidrotic eczema resistant to corticosteroids, iontophoresis, and phototherapy who responded to 1.5 g of mycophenolate mofetil administered twice daily with complete clearing in 4 weeks. The dose was tapered gradually over 12 months without recurrence.[82] In another case report, mycophenolate-mofetil-induced, biopsy-proven dyshidrotic eczema was seen, which resolved on discontinuation of mycophenolate mofetil and again appeared on starting the same.[100,101]

Beneficial role of azathioprine in doses 50-100 mg/day is found in chronic recalcitrant hand eczema recently.[83,102]

In different studies, oral retinoids were found to be useful in chronic hand eczema refractory to corticosteroids. Capella[86] investigated the use of acitretin 25-50 mg/day for 1 month, versus a conventional topical treatment (betamethasone and salicylic acid ointment). Forty-two patients with chronic hyperkeratotic palmoplantar eczema were enrolled in this single-blind and matched-sample design trial. The oral retinoid was significantly better than the topical treatment after 30 days with significant persistence 5 months after suspension of acitretin.

Ruzicka[84] used three different doses of 9-cis-retinoic acid, another retinoid (alitretinoin) in comparison with placebo capsules. This trial was a randomized double-blind multicenter study with 319 participants. The patients were allowed to use standard emollients. In addition, they underwent treatment with 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, or placebo capsules daily for 12 weeks. Significant differences were found in terms of clearance or almost clearance in all alitretinoin groups compared to the placebo group. Statistically significant differences were also reported for reduction in severity (improvement in dermatological life quality index) in all intervention groups. This was true for participant and investigator scoring.

In a phase 3 trial, Ruzicka[85] assessed the efficacy and safety of alitretinoin in the treatment of severe chronic hand eczema refractory to topical corticosteroids. A total of 1032 patients from a total of 111 outpatient clinics in Europe and Canada were randomized in this double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective multicenter trial. The patients received placebo, 10 mg or 30 mg of oral alitretinoin once daily for up to 24 weeks. The Physician's Global Assessment was used to determine overall chronic hand eczema severity, with a response defined as clear or almost clear hands. Patients in the 30 mg group responded better than in the 10 mg group. A total of 48% of patients treated with 30 mg of alitretinoin showed a response with 75% mean reduction in disease signs and symptoms.

It was observed that adequate iron intake reduces nickel absorption from intestine. Iron is absorbed in preference to nickel by divalent metal transporter (DMT) because of high affinity. So because of downregulation uptake of nickel is decreased.[101] In a comparative study of 23 nickel sensitive chronic vesicular hand eczema (CVHE) patients, low nickel diet along with 30 mg of oral iron (n = 12, duration = 12 weeks) was found superior to low nickel diet alone (n = 11) in bringing faster reduction in the severity of CVHE in nickel sensitive patients.[90] Ten patients out of 12 (83.3%) showed complete clearance in study group at the end of 12 weeks with no recurrence, while in the control group five patients (5/11, 45.5%) showed complete clearance at the end of study. There was significant decrease in levels of nickel in the study group.

What is new?

This is a comprehensive review on etiology, classification, treatment and various other aspects of hand eczema.

This review gives an update on hand eczema management.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Willan R. London, England: Johnson; 1808. On Cutaneous Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menne T, Maibach HI. Philadelphia: Boca Raton CRC Press; 1994. Hand Eczema. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elston DM, Ahmed DD, Watsky KL, Schwarzenberger K. Hand dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:291–9. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meding B, Swanbeck G. Consequences of having hand eczema. Contact Dermatis. 1990;23:6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lantinga H, Nater JP, Coenraads PJ. Prevalence incidence and course of eczema on the hands and forearms in a sample of general population. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:135–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1984.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berth-Jones J. Eczema, lichenification, prurigo and erythrodema. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 23–13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meding B, Swanbeck G. Prevalence of hand eczema in an industrial city. Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:627–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rea JN, Newhouse ML, Halil T. Skin disease in Lambeth: A community study of prevalence and use of medical care. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976;30:107–114. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fregert S, Hjorth N, Magnusson B, Bandmann HJ, Calnan CD, Cronin E, et al. Epidemiology of contact dermatitis. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1969;55:17–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrup G. Hand eczema and other dermatoses in South Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol. 1969;49:1–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma VK, Kaur S. Contact dermatitis of hands in Chandigarh. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh CL. Prevalence of contact allergy by sex, race and age. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14:237–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edman B. Sites of contact dermatitis in relationship to particular allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:129–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meding B, Wrangsjö K, Järvholm B, Person J, Thorn D, Raut M, et al. Survey based assessment of prevalence and severity of chronic hand dermatitis in a managed care organisation. Cutis. 2006;77:385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meding B, Swanbeck G. Predictive factors for hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;23:154–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb04776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thestrup- Pederson K, Larsen CG, Ronnerig J. The immunology of contact dermatitis. A review with special reference to the pathophysiology of eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;20:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1989.tb03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr MM, Botham PA, Gaahrodgen DJ. Early cellular reactions induced by Dinitrochlorbenzene in sensitized humans. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:637–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias PM, Schmuth M. Abnormal skin barrier in the etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009;9:265–72. doi: 10.1007/s11882-009-0037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevilla LM, Nachat R, Groot KR, Klement JF, Uitto J, Djian P, et al. Mice deficient in involucrin, envoplakin, and periplakin have a defective epidermal barrier. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1599–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morar N, Edster P, Street T, Weidinger S, Di WL, Dixon A, et al. Fine mapping of susceptibility genes for atopic dermatitis in the epidermal differentiation complex on chromosome 1q21. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, et al. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1151–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middleton JD. The mechanism of action of surfactants on the isolated stratum corneum. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1969;20:399–412. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egelrud T, Brattsand M, Kreutzmann P, Walden M, Vitzithum K, Marx UC, et al. hK5 and hK7, two serine proteinases abundant in human skin, are inhibited by LEKTI domain 6. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1200–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson B, Horn T, Sander C, Kohler S, Smoller B. Expression of stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme in ichthyoses and squamoproliferative processes. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:358–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson L, Bäckman A, Ny A, Edlund M, Ekholm E, Hammarström B, et al. Epidermal over expression of stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme in mice: A model for chronic itchy dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:444–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajaj AK, Saraswat A, Mukhija G, Rastogi S, Yadav S. Patch testing experience with 1000 patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:313–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.34008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishore NB, Belliappa AD, Shetty NJ, Sukumar D, Ravi S. Hand eczema- clinical patterns and role of patch testing. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:207–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur S, Sharma VK. Contact dermatitis of hands in Chandigarh. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:103–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajaj AK. Contact dermatitis of hands. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1983;49:195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh G, Singh K. Contact dermatitis of hands. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:152–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasricha JS, Kanwar AJ. Substances causing contact dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Lepr. 1978;44:264–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruynzeel DP, de Boer EM, Brouwer EJ, de Wolff FA, de Haan P. Dermatitis in bulb growers. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:11–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen J. The occurrence and course of skin symptoms of the hands among female cleaners. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:284–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forsbeck M, Skog E, Asbrink E. Atopic hand dermatitis: A comparison with atopic dermatitis without hand involvement, especially with respect to influence of work and development of contact sensitization. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1983;63:9–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meding B, Swanbeck G. Epidemiology of different types of hand eczema in an industrial city. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1989;69:227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson EL, Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Prevalence and morphology of hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2006;17:123–7. doi: 10.2310/6620.2006.06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warshaw EM. Therapeutic options for chronic hand dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:240–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissonnette R, Diepgen TL, Elsner P, English J, Graham-Brown R, Homey B, et al. Redefining treatment options in chronic hand eczema (CHE) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diepgen TL, Agner T, Aberer W, Berth-Jones J, Cambazard F, Elsner P, et al. Management of chronic hand eczema. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diepgen TL, Andersen KE, Brandao FM, Bruze M, Bruynzeel DP, Frosch P, et al. Hand eczema classification: A cross-sectional, multicentre study of the aetiology and morphology of hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:353–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lodi A, Betti R, Chiarelli G, Urbani CE, Crosti C. Epidemiological, clinical and allergological observations on pompholyx. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minocha YC, Dogra A, Sood VK. Contact sensitivity in palmer hyperkeratotic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1983;59:60–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabroe RA, Sharp LA, Peachey R. Contact allergy to gold thiosulfate. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:345–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Córdoba S, Sánchez-Pérez J, García-Díez A. Ring dermatitis as a clinical presentation of fragrance sensitization. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calnan CD. Eczema for me. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1968;54:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cronin E. Clinical patterns of hand eczema in women. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:153–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1985.tb02528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hjorth N. Gut eczema in slaughterhouse workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1978;4:49–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1978.tb03721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkelmann RK, Gleich GJ. Chronic acral dermatitis: Association with extreme elevations of IgE. JAMA. 1973;225:378–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.225.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maibach HI, Johnson HL. Contact urticaria syndrome: Contact urticaria to diethyltoluamide (immediate- type hypersensitivity) Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:726–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.111.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fregert S. 2nd edition. Copenhagen: Munksgaard Publishers; 1981. Manual of Contact Dermatitis. On behalf of the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fischer TI, Maibach HI. The thin layer rapid use epicutaneous test (TRUE-test), a new patch test method with high accuracy. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:63–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lachapelle JM. A left versus right side comparative study of Epiquick patch test results in 100 consecutive patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;20:51–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1989.tb03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harding CR. The stratum corneum: Structure and function in health and disease. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04s1001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bock M, Wulfhorst B, Gabard B, Schwanitz HJ. Efficacy of skin protection creams for the treatment of irritant dermatitis in hairdresser apprentices. Occup Environ Dermatol. 2001;49:73–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mygind K, Sell L, Flyvholm MA, Jepsen KF. High-fat petrolatum-based moisturizers and prevention of work-related skin problems in wet-work occupations. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bielfeldt S, Wehmeyer A, Rippke F, Tausch I. Efficacy of a new hand care system (cleansing oil and cream) in a model of irritation and by atopic eczema. Dermatosen. 1998;46:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lodén M, Wirén K, Smerud K, Meland N, Hønnås H, Mørk G, et al. Treatment with a barrier-strengthening moisturizer prevents relapse of hand eczema. An open, randomized, prospective, parallel group study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:602–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moller H, Svartholm H, Dahl G. Intermittent maintenance therapy in chronic hand eczema with clobetasol propionate and flupredniden acetate. Curr Med Res Opin. 1983;8:640–4. doi: 10.1185/03007998309109812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uggeldahl PE, Kero M, Ulshagen K, Solberg VM. Comparative effects of desonide cream 0.1% and 0.05% in patients with hand eczema. Curr Ther Res. 1986;40:969–73. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gupta AK, Shear NH, Lester RS, Baxter ML, Sauder DN. Betamethasone dipropionate polyacrylic film-forming lotion in the treatment of hand-dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:828–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veien NK, Larsen PO, Thestrup-Pedersen K, Schou G. Long-term, intermittent treatment of chronic hand eczema with mometasone furoate. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:882–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grattan CE, Carmichael AJ, Shuttleworth GJ, Foulds IS. Comparison of topical PUVA with UVA for chronic vesicular hand eczema. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1991;71:118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schempp CM, Muller H, Czech W, Schopf E, Simon JC. Treatment of chronic palmoplantar eczema with local bath-PUVA therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:733–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stege H, Berneburg M, Ruzicka T, Krutmann J. Cream PUVA photochemotherapy. Hautarzt. 1997;48:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s001050050551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanifin JM, Stevens V, Sheth P, Breneman D. Novel treatment of chronic severe hand dermatitis with bexarotene gel. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:545–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schnopp C, Remling R, Mohrenschlager M, Weigl L, Ring J, Abeck D. Topical tacrolimus (FK506) and mometasone furoate in treatment of dyshidrotic palmar eczema: A randomized, observer-blinded trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:73–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.117856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thelmo MC, Lang W. An open-label pilot study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topically applied tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of hand and/or foot eczema. J Dermatol Treat. 2003;14:136–40. doi: 10.1080/09546630310009491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Belsito DV, Fowler JF. Pimecrolimus cream 1%: A potential new treatment for chronic hand dermatitis. Cutis. 2004;73:31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cherill R, Tofte S, Meyer K, Hanifin J. SDZ ASM 981 is effective in the treatment of chronic irritant hand dermatitis: A 6-week randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, single centre study. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:16–7. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thaçi D, Steinmeyer K, Ebelin ME, Scott G, Kaufmann R. Occlusive treatment of chronic hand dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1% results in low systemic exposure, is well tolerated, safe, and effective: An open study. Dermatology. 2003;207:37–42. doi: 10.1159/000070939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Egawa K. Topical vitamin D3 derivatives in treating hyperkeratotic palmoplantar eczema: A report of five patients. J Dermatol. 2005;32:381–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hill VA, Wong E, Corbett MF, Menday AP. Comparative efficacy of betamethasone/clioquinol (Betnovate-C) cream and betamethasone/fusidic acid. J Dermatolog Treat. 1998;9:15–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fowler JF. A skin moisturizing cream containing quaternium-18-bentonite effectively improves chronic hand dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:201–5. doi: 10.1007/s102270000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fowler JF. Efficacy of skin protective foam in the treatment of chronic hand dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11:165–9. doi: 10.1053/ajcd.2000.7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bollag W, Ott F. Successful treatment of chronic hand eczema with oral 9-cis-retinoic acid. Dermatology. 1999;199:308–12. doi: 10.1159/000018280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Odia S, Vocks E, Rakosi J, Ring J. Successful treatment of dyshidrotic hand eczema using tap water iontophoresis with pulsed direct current. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1996;76:472–4. doi: 10.2340/0001555576472474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Coevorden AM, Kamphof WG, van Sonderen E, Bruynzeel DP, Coenraads PJ. Comparison of oral psoralen-UV-A with a portable tanning unit at home vs hospital administered bath psoralen-UV-A in patients with chronic hand eczema. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1463–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosen K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. Chronic eczematous dermatitis of the hands: A comparison of PUVA and UVB treatment. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1987;67:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Granlund H, Erkko P, Eriksson E, Reitamo S. Comparison of the influence of cyclosporine and topical betamethasone-17,21-dipropionate treatment of severe chronic hand eczema. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1996;76:371–6. doi: 10.2340/0001555576371376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Egan CA, Rallis TM, Meadows KP, Krueger GG. Low dose oral methotrexate treatment for recalcitrant palmoplantar pompholyx. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:612–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pickenacker A, Luger T, Schwarz T. Dyshidrotic eczema treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:378–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scerri L. Azathioprine in dermatological practice. An overview with special emphasis on its use in non- bullous inflammatory dermatoses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruzicka T, Larsen FG. Oral alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) therapy for chronic hand dermatitis in patients refractory to standard therapy. Results of a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1453–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ruzicka T, Lynde CW, Jemec GB, Diepgen T, Berth-Jones J, Coenraads PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety or oral alitretinoin (9-cis retinoic acid) in patients with severe chronic hand eczema refractory to topical corticosteroids: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:808–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Capella GL, Fracchiolla C, Frigerio E, Altomare G. A controlled study of comparative efficacy of oral retinoids and topical betamethasone/salicylic acid for chronic hyperkeratotic palmoplantar dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:88–93. doi: 10.1080/09546630410027814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Veien NK, Kaaber K, Larsen PO, Nielsen AO, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Ranitidine treatment of hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis: A double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1056–7. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whitaker DK, Cilliers J, deBeer C. Evening primrose oil (Epogam) in the treatment of chronic hand dermatitis: Disappointing therapeutic results. Dermatology. 1996;193:115–20. doi: 10.1159/000246224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharma AD. Disulfiram and low nickel diet in the management of hand eczema: A clinical study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:113–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burrows D, Rogers S, Beck M, Kellet J, McMaster D, Merrett D, et al. Treatment of nickel dermatitis with trientine. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;15:55–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Menné T, Kaaber K. Treatment of pompholyx due to nickel allergy with chelating agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1978;4:289–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1978.tb04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pigatto PD, Gibelli E, Fumagalli M, Bigardi A, Morelli M, Altomare GF. Disodium cromoglycate versus diet in the treatment and prevention of nickel-positive pompholyx. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1990.tb01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sharma AD. Iron therapy in hand eczema: A new approach for management. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:295–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cartwright PH, Rowell NR. Comparison of Grenz rays versus placebo in the treatment of chronic hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:73–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fairris GM, Mack DP, Rowell NR. Superficial X-ray therapy in the treatment of constitutional eczema of the hands. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:445–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb06607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.King CM, Chalmers RJG. A double-blind study of superficial radiotherapy in chronic palmar eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:451–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb06608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fairris GM, Jones DH, Mack DP, Rowell NR. Conventional superficial X-ray versus Grenz ray therapy in the treatment of constitutional eczema of the hands. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:339–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb04862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mittal A, Khare AK, Gupta L, Mehta S, Garg A. Use of methotrexate in recalcitrant eczema. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:224. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.80434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cronstein BN. The mechanism of action of methotrexate. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23:739–55. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Semhoun-Ducloux S, Ducloux D, Miguet JP. Mycophenolate mofetil-induced dyshidrotic eczema. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:417. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tallvist J, Bowlus CL, Lonnerdal B. Effect of iron treatment on nickel absorption and gene expression of the divalent metal transporter (DMT1) by human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;92:121–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Agarwal US, Besarwal RK. Topical clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream alone and in combination with azathioprine in patients with chronic hand eczema: An observer blinded randomized comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:101–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.104679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]