Abstract

Low-copy repeats, or segmental duplications, are highly dynamic regions in the genome. The low-copy repeats on chromosome 22q11.2 (LCR22) are a complex mosaic of genes and pseudogenes formed by duplication processes; they mediate chromosome rearrangements associated with velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome, der(22) syndrome, and cat-eye syndrome. The ability to trace the substrates and products of recombination events provides a unique opportunity to identify the mechanisms responsible for shaping LCR22s. We examined the genomic sequence of known LCR22 genes and their duplicated derivatives. We found Alu (SINE) elements at the breakpoints in the substrates and at the junctions in the truncated products of recombination for USP18, GGT, and GGTLA, consistent with Alu-mediated unequal crossing-over events. In addition, we were able to trace a likely interchromosomal Alu-mediated fusion between IGSF3 on 1p13.1 and GGT on 22q11.2. Breakpoints occurred inside Alu elements as well as in the 5′ or 3′ ends of them. A possible stimulus for the 5′ or 3′ terminal rearrangements may be the high sequence similarities between different Alu elements, combined with a potential recombinogenic role of retrotransposon target-site duplications flanking the Alu element, containing potentially kinkable DNA sites. Such sites may represent focal points for recombination. Thus, genome shuffling by Alu-mediated rearrangements has contributed to genome architecture during primate evolution.

Segmental duplications, or low-copy repeats (LCRs) of >95% sequence identity, cluster within different chromosome regions and constitute approximately 5% of the human genome (Cheung et al. 2001; Bailey et al. 2002a). Low-copy repeats range in size from 10-250 kb (Stankiewicz and Lupski 2002). They are considered highly dynamic regions in the genome because they mediate meiotic unequal nonallelic homologous recombination events, resulting in altered gene dosage associated with human genomic disorders (Stankiewicz and Lupski 2002). Hemizygous deletions mediated by meiotic homologous recombination events in LCRs occur in several well characterized disorders including Williams-Beuren syndrome at chromosome band 7q11.23 (OMIM 194050), Prader-Willi (OMIM 176270) and Angelman syndromes (OMIM 105830) on chromosome 15q12, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP; OMIM 162500) on 17p12, and Smith-Magenis syndrome (OMIM 182290) on chromosome 17p11.2. In some cases, the reciprocal product of an interchromosomal recombination event occurs, resulting in a duplication of the interval; these disorders include Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A (OMIM 118220) on 17p12 and dup(17)(p11.2p11.2) (Potocki et al. 2000). Three different disorders on 22q11.2—velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome (VCFS/DGS; OMIM192430/OMIM188400), der(22) syndrome (Zackai and Emanuel 1980) and cat-eye syndrome (CES; MIM 115470)—are also associated with rearrangements involving region-specific LCRs (LCR22).

LCR-mediated rearrangements occur sporadically in different populations as de novo events and together have a large impact on human health. Unfortunately, very little is understood about the precise mechanisms by which LCRs mediate chromosome rearrangements, thereby causing disease. It is also not known how the LCRs formed during the evolution of primate species. This is relevant, as it is possible that similar mechanisms are responsible for mediating meiotic rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. With the availability of the complete sequence of the human genome, it is now possible to define the mechanisms responsible for shaping the LCRs during evolution.

In addition to genes and pseudogenes, LCRs, like the rest of the genome, contain highly repetitive elements such as LINEs (long interspersed repetitive elements) and SINEs (short interspersed nuclear elements). These elements, particularly SINEs, have been implicated in chromosome rearrangements and disease. Alu elements are part of the SINE (short interspersed nuclear elements) family of transposable elements, and they comprise 10% of the human genome (Lander et al. 2001). Alu elements are approximately 280 bp in length and consist of two similar monomers that bear similarity to 7SL RNA, which is a major component of the signal recognition particle involved in attaching ribosomes to the endoplasmic reticulum. RNA polymerase III transcribes the Alu elements (Duncan et al. 1979). Different Alu subfamilies have formed and become mobilized at different times in the evolution of primate species (Jurka and Pethiyagoda 1995). The subfamilies (70%-98% homologous) can be identified by examining their sequence content at specific diagnostic nucleotides.

The role of Alu SINEs in modulating the architecture of the human genome in association with human disorders and in mediating gene rearrangements is well documented (Batzer and Deininger 2002; Kolomietz et al. 2002). The two most frequent mechanisms for modulating architecture by Alu elements are by transposition and unequal homologous recombination. Both mechanisms have been linked to human diseases (see Table 1 in Kolomietz et al. 2002). As mentioned above, Alu SINEs are the most widespread class of transposable elements, with about one million copies in the genome (Lander et al. 2001). Moreover, Alu elements are more frequent in GC- and gene-richregions than are other retrotransposons such as LINEs and endogenous retroviruses. Unlike Alu elements, LINES are underrepresented, truncated, or rearranged (Lander et al. 2001). Thus, Alu elements are a likely substrate for recombination events in gene-richregions, as they provide targets for such events. However, the role of Alu elements in shaping the architecture of segmental duplications (low-copy repeats) in the primate genome has not been demonstrated.

Table 1.

Positions of LCR22s

| LCR22 | Begins | Ends | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 15582996 | 15824819 | 241823 |

| ADU | 15924965 | 15926455 | 1490 |

| 15945797 | 15947086 | 1289 | |

| 3a | 17248464 | 17433656 | nd |

| 3b | 17740485 | 17752123 | 11627 |

| 4 | 18164256 | 18409514 | 245258 |

| 5 | 19661949 | 19696275 | 34326 |

| 6 | 20347738 | 20362731 | 14993 |

| 20419414 | 20442294 | 22880 | |

| 20505214 | 20529866 | 24652 | |

| 7 | 21329062 | 21360773 | 31711 |

| 8 | 21700353 | 21790369 | 90016 |

| Interval | 15597234 | 21790369 | |

| Totals | 6193135 | 720065 | |

| % | 11.63% |

Alu SINES can conceivably mediate some of the dynamic processes forming segmental duplications or LCRs in evolution. This might ultimately shed light on the recombination mechanisms responsible for the etiology of genomic disorders. Here we present our analysis of the genomic sequence of chromosome 22q11.2 to identify mechanisms shaping LCRs on this chromosome (LCR22s) during evolution. The approach taken was to map the breakpoints within the substrates and products of rearrangements. We present here evidence for specific Alu-mediated mechanisms in shaping the genes within LCRs.

RESULTS

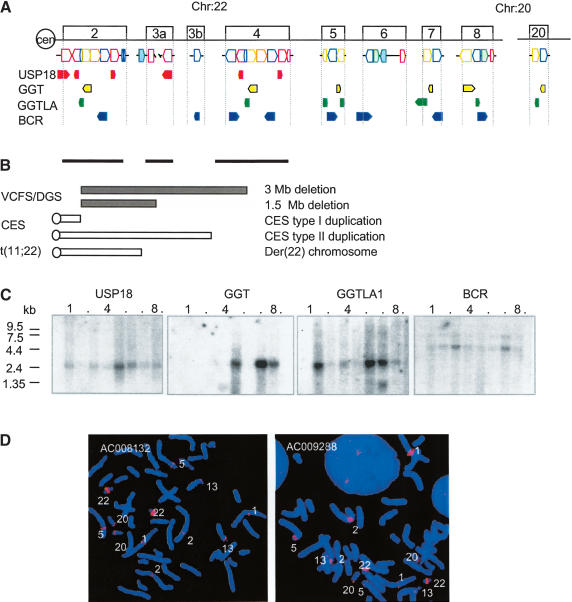

To uncover sequence relationships comprising the minimal tiling path of clones across the 22q11.2 region, we used miropeats software (Parsons 1995) following removal of high-copy repetitive elements from the analysis (RepeatMasker; http://ftp.genome.washington.edu/cgi-bin/RepeatMasker/; Repbase Update libraries; Jurka 2000). Those bearing homologies to each other comprise LCRs. LCR22s constitute the majority of LCRs on 22q11.2 and share sequences with those LCRs that mediate the common chromosome 22q11.2 disorders (Edelmann et al. 1999a; Shaikh et al. 2000). After examining their relationships with each other, we delineated the borders of the LCR22s using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) and BLAT (Kent 2002) analyses. LCR22s were found to comprise 11.6% of the 6-Mb 22q11.2 interval (Table 1). Some LCR22s are large, such as LCR22-2 and LCR22-4, which are both 240 kb in size (Table 1). LCR22-3a, situated between the two, contains an uncloned region within; thus, its size is unknown. Some LCR22s are quite small—less than 2 kb. As shown in Figure 1A, the LCR22s are composed of blocks or modules forming a complex pattern. Most of them appear to be partial duplicates of each other (Fig. 1A). The two greatest in size, LCR22-2 and LCR22-4, contain a large region of overall direct orientation (Fig. 1A; Shaikh et al. 2000). Homologous recombination events between these two LCR22s mediate recurrent 22q11.2 rearrangements associated with VCFS/DGS and CES (Fig. 1B; Edelmann et al. 1999b). Thus, these two intervals, due to their high degree of direct identity (97%-99%; Shaikh et al. 2000), are excellent substrates for unequal crossing-over events. That the two LCR22s share a large region of homology to each other suggests that they evolved from a common progenitor.

Figure 1.

(A) Genes in the LCR22s. Four functional genes, USP18 (red), GGT (yellow), GGTLA (green), and BCR (blue) map to LCR22-2, LCR22-8, LCR22-7 and LCR22-6, respectively. Each has become copied during evolution, resulting in a complex pattern within blocks comprising LCR22s (colored blocks corresponding to LCR22 genes, orientation shown). The orientation of the genes and pseudogene copies with respect to the centromere is indicated. (B) Chromosome rearrangement disorders on 22q11.2. The bars under LCR22-2, LCR22-3a, and LCR22-4 depict the intervals harboring the common deletion endpoints, duplication endpoints, and translocation breakpoints in patients with VCFS/DGS, CES, and der(22) syndrome, respectively. (C) Northern blot analysis. We performed a Northern blot analysis using expression sequence tag (EST) DNA probes for USP18, GGT, GGTLA, and BCR. Autoradiograms of human multitissue Northern blots (Clontech) containing heart, brain (whole), placenta, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, and pancreas tissues were probed with radiolabeled PCR products from ESTs. The USP18, GGT, and BCR probes are derived from the last exon (except for USP18 in LCR22-3a), which would recognize all of the duplicated copies of each on chromosome 22 if transcribed. The band sizes for BCR are 4.79 kb, 7.50 kb; the expected sizes were 2.6 kb and 4.7 kb. The band sizes for GGT are 1.29 kb and 3.00 kb; the expected sizes were 1.8 kb and 2.5 kb. The band sizes for GGTLA are 1.58 kb and 2.8 kb; the expected size was 2.4 kb. The band size for USP18 is 1.95 kb; the expected size was 1.8 kb. (D) Low-stringency FISH mapping. Probes from LCR22-2 (GenBank AC008132) and LCR22-4 (GenBank AC009288) were used for low-stringency FISH mapping. Hybridization signals were detected in the vicinity of chromosomes 1p13, 2p11, 5p13, 13p11, and 20p12. The strongest signals were detected on chromosome 22q11, due to the presence of multiple copies of sequences contained within the LCR22 clones.

As mentioned, both genes and pseudogenes lie within the LCR22s. Some of the genes have been well characterized (Heisterkamp and Groffen 1988). The four known genes in the LCR22s are USP18 (Schwer et al. 2000), GGT (Rajpert-De Meyts et al. 1988), GGTLA (Heisterkamp et al. 1991; Morris et al. 1993), and BCR (Heisterkamp et al. 1985). USP18 maps to LCR22-2, GGT maps to LCR22-8, GGTLA maps to LCR22-7, and BCR maps to LCR22-6 (Fig. 1A). Parts of each therein have been duplicated, forming truncated unprocessed pseudogenes, comprising the block structure of LCR22s (Fig. 1A). Selected components of each gene were duplicated, suggesting that specific mechanisms were responsible for the duplication process.

Northern blot analysis was performed to determine the pattern of expression of the four known genes and to ascertain whether the smaller pseudogene copies are expressed. Each of the four genes were expressed as full length-transcripts in multiple tissues, and showed distinctive patterns of expression, suggesting that they are each subjected to their own transcriptional regulation (Fig. 1C). In general, the unprocessed pseudogenes, which would generate different-sized transcripts, were not strongly expressed.

We were interested in whether these genes map exclusively to chromosome 22q11.2 or elsewhere in the genome. To detect additional copies, we performed low-stringency fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) mapping of normal metaphase chromosomes. Examination of the sequence of the human genome revealed copies of the LCR22 genes on the chromosomal regions 1p13, 2p11, 5p13, 13p11, and 20p12, which coincide with most of the signals detected by low-stringency FISH (Fig. 1D). This was similar to what was previously observed using different probes on 22q11.2 (Bailey et al. 2002b).

Duplication and Transposition of USP18

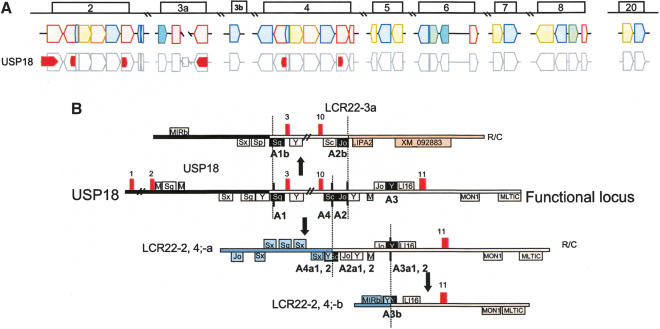

To understand how the genes and pseudogene copies in the LCR22s formed (Fig. 1A), we performed a BLAT analysis and compared the genomic structure of the full-length gene and pseudogene copies. This was done with no model or bias for what sequences could lie within the breakpoints. We began with an analysis of the sequence for the most centromeric gene, termed USP18 (Schwer et al. 2000), in LCR22-2 (Fig. 1A). The gene/pseudogene copies of USP18 in LCR22-2, -3a, and -4, illustrated in Figure 1A, are shown in more detail within the block structure of the LCR22s in Figure 2A. Using the tracks for known genes and high-copy repetitive elements in the UCSC browser (Kent 2002) as a guide, we traced the intervals surrounding the breakpoints within the ancestral USP18 gene and the junctions of the duplicated pseudogene copies (Fig. 2B). We found that exons 3-10 of USP18 became duplicated to LCR22-3a, whereas the last exon, exon 11, became duplicated to two locations in LCR22-2 (Fig. 2B, red blocks; LCR22-2-a, b) and to two locations in LCR22-4 (red blocks; LCR22-4-a, b). The first feature that was particularly striking was the presence of Alu elements at breakpoints in the ancestral USP18 locus and junctions in the duplicated copies (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Position of USP18 within the block structure of the LCR22s. Each of the LCR22s are ordered with respect to the centromere of chromosome 22q11.2. The block structure of LCR22 was created using miropeats software to detect sequence relationships. The colors of the blocks were chosen to be coordinated with the genes within. The USP18 gene (red) is shown in its proper transcription orientation. The position of the functional USP18 locus (most centromeric copy in LCR22) and its unprocessed pseudogene copies within the LCR22 block structure are shown. (B) Duplication events for USP18. The exons (numbered red boxes) and high-copy repeating elements are shown (in a “+” orientation above the line and in a “-” orientation below the line. Alu elements are indicated by the subfamily. Mer elements (abbreviated as “M”) were drawn as tracked by RepeatMasker (UCSC browser; June 2002 assembly) in the vicinity of the USP18 functional locus as shown (11 exons; chr22:15573184-15600410). R/C, reverse and complement. The position of the breakpoints in the USP18 functional locus (substrate) and junctions in the duplicated copies (products) are indicated with a vertical line separating the juxtaposed intervals, shown in different colors depending on the LCR22 block to which they map. The Alu elements involved in the recombination events have black fill. The positions of the breakpoints in LCR22-2 that are shown are 15685023-15689864 (LCR22-2), 18244496-18249337 (LCR22-4), and 17418000-17420692 (LCR22-3a). A different breakpoint in the interval between exons 10 and 11 occurred, creating the copy in LCR22-2, shown at positions 15790288-15794241 and LCR22-4 at 18351456-18355409. For more details see Supplemental Figures 1-3.

The breakpoints on either side of USP18 exons 3-10, creating the copy in LCR22-3a, were in the vicinity of Alu elements (Fig. 2B, A1, A2, black filled boxes; Supplemental Fig. 1 online at http://www.girinst.org/server/supplement/03_babcock/index.html). One of them, Alu A1, is located between exons 2 and 3 of USP18. Sequences on one side of this Alu were present in the ancestral USP18 locus but absent from the duplicated copy in LCR22-3a. On the other hand, sequences on the other side were present in the unprocessed pseudogene copy in LCR22-3a. A similar situation occurred for the region surrounding the other Alu, termed A2 (Fig. 2B). Sequences on one side of this Alu are present in the ancestral locus of USP18, but sequences on the other side of the Alu are missing from the LCR22-3a copy. Alu A2 thus lies in the vicinity of the breakpoint (Fig. 2B). Alu A1 and its copy, A1b and Alu A2-A2b are more closely related to each other than to any other Alu element in the genome (Suppl. Figs. 1,2), indicating that they are copies rather than independent insertions.

LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 each have two separate copies of USP18 exon 11 (Fig. 2A). The more proximal copy in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (LCR22-2a, LCR22-4a) are similar to each other, and they have a larger region deriving from the USP18 ancestral locus than the more distal copy in both LCR22s (LCR22-2b, LCR22-4b). To determine how the copies were formed, we performed a BLAT analysis of the exon 10-11 interval of USP18. Examination of the proximal copy showed that exon 11 became juxtaposed to sequences deriving from the vicinity of another LCR22 block, harboring BCR and the predicted gene, DKFZ434p211 (Fig. 2A,B, blue block, LCR22-6). To form this copy of exon 11, a breakpoint occurred in the vicinity of Alu A4 (Alu Sc; Suppl. Fig. 3). This conclusion was reached because sequences on one side of the Alu A4 are derived from LCR22-6, whereas sequences on the other side of Alu A4 are derived from the ancestral USP18 locus.

The most distal copy of exon 11 (LCR22-2b, LCR22-4b) has a smaller region derived from the ancestral USP18 locus. To generate this copy, a breakpoint occurred in the vicinity of Alu A3 (Fig. 2B; Suppl. Figs. 2,3). This was deduced by examining the sequences at the breakpoints and junctions. After discovering an Alu at the breakpoint junction, we carefully examined the sequences that flank either side of the Alu. Thus, sequences proximal to the copy of Alu A3 (copy termed Alu A3b) are present in LCR22-6, whereas sequences distal are present in the ancestral locus of USP18. Alu A3, A3b1 (copy in LCR22-2b) and A3b2 (copy in LCR22-4b) are highly related to each other, eliminating the possibility of independent insertions (Suppl. Fig. 2).

The images depicted in Figure 2B are shown more concisely in Figure 3A,B. In these figure panels, Alus A1, A2, A3, and A4 in USP18 and their copies are illustrated in their proper orientation within the blocks comprising LCR22-2, -3a, and -4 (Fig. 3A). We were interested in whether the Alu elements formed the borders of LCR22 blocks, because this would suggest that they participated in shaping the LCR22s during evolution. As we anticipated, Alu A1 demarcates the beginning of LCR22-2, and Alu A1b represents the distal end of LCR22-3a. A breakpoint in Alu A2 resulted in a slightly truncated product (A2b; Suppl. Fig. 1). A breakpoint in Alu A4 was responsible for the generation of the copy of USP18 in LCR22-2a and -4a (Fig. 3A,B). A breakpoint within Alu A3 was responsible for the movement of the smallest part of the exon 11 region of USP18 to LCR22-2b and LCR22-4b (Fig. 3A,B). These breakpoints demarcate the junctions between blocks comprising LCR22-2 and -4 (Fig. 3A) and thus form the borders of modules.

Figure 3.

(A) Position of Alu elements involved in USP18 copies in LCR22-2, -3a, and -4. The USP18 gene (light red shapes; exonic orientation shown) within the block structure of LCR22-2, -3a, and -4 is shown. Alu elements A1 (black), A2 (gray), and A3(white) are illustrated in the “+” or “-” orientation. The duplicated copies of the Alu elements within their respective copies of USP18 are illustrated. (B) LCR22 breakpoints occurred within Alu elements. The position of the Alus (A1, black; A4, light gray; A2, dark gray; A3, white) at the breakpoints (dotted line) in the USP18 functional locus (light red) and copies are shown. (C) Alus involved in breakpoints with respect to the genomic organization of USP18. The genomic organization of USP18 was determined by comparing the cDNA sequence with the human genomic sequence by BLAST analysis. The position of Alus A1, A2, A3, and A4 with respect to genomic organization of USP18 is illustrated (dotted line). (D) Structure of Alu elements A1, A2, A3, and A4, and their duplicated copies. Each Alu monomer (red, pink) is illustrated on either side of the A-rich spacer (blue). The 3′ poly A tail is shown (black). Alu A1 and its copy, A1b in LCR22-3a, contain the first monomer and spacer only, and both are part of the Alu Sq family. Alu A2, Alu Jo, and its copy in LCR22-3a, A2b are shown. The 5′ part of the Alu is not part of the Alu Jo subclass (yellow box). Alu A4 is a member of the Alu Sc subclass. The duplicated copies, A4a1 and A4a2, are chimeric, composed in part with sequences from A4 and part from another Alu (yellow box). Alu A3 and its copies, A3b1, A3b2, A3a1, and A3a2 are illustrated. Alus A3b1 and A3b2 contain only the second monomer and poly A site from Alu A3 and the rest from another Alu element (yellow). More details are provided in the Supplemental Figures 1-3.

The positions of Alus A1, A2, A3, and A4 are shown with respect to the genomic organization of USP18 and its unprocessed pseudogene copies in Figure 3C. This shows that the breakpoints at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene in LCR22-2, -3a, and -4 can be explained by Alu-mediated events. We examined the high-copy repetitive sequence content in the 27,228-bp USP18 gene locus on 22q11.2 using RepeatMasker. Repeats comprise 59% of the gene locus: Alus comprise 24.5%, LINE1 elements comprise 20%, and LTR-retrotransposons comprise 9%. Their proportions being equal, if the appearance of Alu elements at the breakpoints were simply by chance, we would expect to see an equal number of LINEs at the breakpoints. However, we found only Alus. Therefore, we do not think the breakpoints occurred in Alu elements by chance.

Next, we were interested in the precise position of the breakpoints in the Alu elements. Alu elements contain two monomers with a spacer in between and a 3′ poly A site (Fig. 3D; Suppl. Figs. 1-3). For Alu A1, an Alu Sq, only one monomer was present in both the ancestral USP18 locus and in the copy present in LCR22-3a (Alu A1b; Fig. 3D). The breakpoint occurred at the 3′ side of the spacer (Fig. 3D, blue bar) between the two monomers, as depicted in red and pink, creating the copy in LCR22-3a (Suppl. Fig. 1 online). For Alu A2, Alu Jo, the breakpoint occurred within the first monomer of the Alu (Suppl. Fig. 1; yellow represents a fusion with another Alu), resulting in the copy in LCR22-3a. Thus, for these two breakpoints creating the truncated copy in LCR22-3a, the precise mechanism could not be discerned. This is not the case for the rearrangements in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4.

The two Alus A4 and A3 were involved in the rearrangements resulting in duplicated copies of USP18 exon 11 in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4. Alu A4 belongs to the Alu Sc subfamily of Alu elements (Fig. 3D). The duplicated copy of Alu A4 in LCR22-2-a and LCR22-4-a (A4a1, A4a2) is chimeric; part derives from Alu A4 and part is from another Alu element (Alu Y; yellow bar, Figs. 2B, 3D). Thus, a homologous recombination event between two Alu elements might have been responsible for creating the chimeric Alu product. Alu A3 is part of the Alu Y or younger Alu subfamily. The duplicated Alu A3 products, A3b1 and A3b2, in LCR22-2-b and LCR22-4-b, respectively, are chimeric as well, and contain part of Alu A3, and part from a different Alu element (Alu Y; yellow bar, Figs. 2B, 3D). Both rearrangements involving these two elements implicate unequal crossover mechanisms.

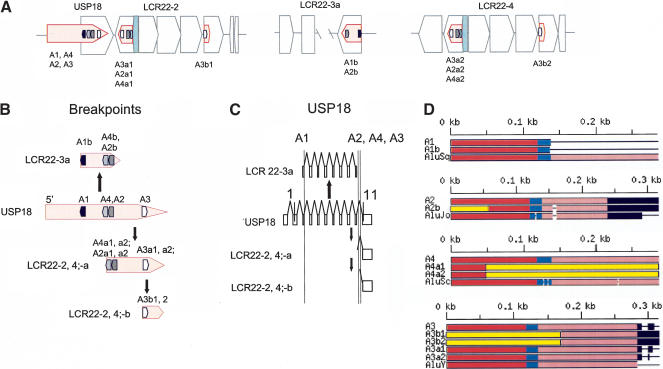

Duplication and Transposition Processes of GGT

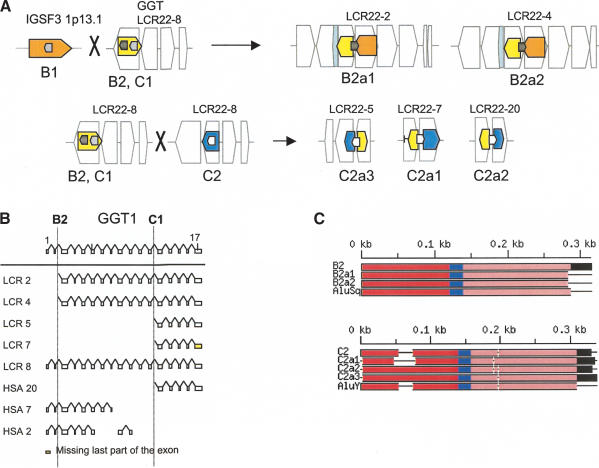

The functional GGT gene (Rajpert-De Meyts et al. 1988) maps to LCR22-8, but unprocessed pseudogene copies (Morris et al. 1993) map to other LCR22s and other loci in the genome (Fig. 1A,D). The genes involved in the duplication process of GGT are shown with respect to the LCR22 block structure in Figure 4A. Exons 2-17 of GGT became duplicated to LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (Fig. 4A,B), whereas exons 13-17 became duplicated onto others (Fig. 4A,B). The overall organization of the genes/pseudogenes for GGT, IGSF3 (functional locus on chromosome 1p13.1), and the predicted gene, DKFZp434p211 involved in the duplication of GGT are illustrated (Fig. 4A). DKFZp434p211 is present in many copies in the genome (Courseaux et al. 2003). On 22q11.2, it is intertwined with BCR (Fig. 4A; Bailey et al. 2002b).

Figure 4.

(A) Positions of GGT, ISGF3, and predicted gene DKFZp434p211 within the block structure of the LCR22s. Each of the LCR22s is ordered with respect to the centromere of chromosome 22q11.2. The block structure of LCR22 was created using miropeats software to detect sequence relationships. The colors of the blocks were chosen to coordinate with the genes within. The GGT (yellow), IGSF3 (orange), and DKFZp434p211 (overlapping with BCR; blue) genes are shown in their proper transcription orientation. The position of the functional GGT locus (LCR22-8) and its unprocessed pseudogene copies within the LCR22 block structure are shown. (B) Recombination events in GGT and IGSF3. GGT exons 3-17 (chr22:21695000-21722900; yellow numbered boxes) became duplicated to LCR22-2 and LCR22-4. IGSF3 (orange; 1p13.1; chr1:117622772-117711984) became juxtaposed to the copies of GGT. R/C, reverse/complement. Both GGT and IGSF3 harbor the Alu S subfamily member (Alu B1, IGSF3; Alu B2, GGT) at the breakpoint junction (Alu B2a1, Alu B2a2, LCR22-2 and LCR22-4, respectively) between the two functional genes (black-filled elements). The products of the recombination are shown (LCR22-2, chr22:15700573-15723288 and LCR22-4, chr22:18260039-18282533). (C) Recombination events in GGT and predicted gene DKFZp434p211. The two substrates, GGT and DKFZp434p211 (overlapping with BCR), are shown. R/C, reverse/complement. Examination of the pattern of exons and high-copy repetitive elements revealed an Alu Y that was present at the junction between the two substrates in the duplicated products of the recombination event (black fill) in LCR22-5, LCR22-7, and LCR20 (Suppl. Fig. 4). The L2 LINE elements upstream of exon 13 in GGT (yellow fill) and the Alu elements upstream exon 1 of DKFZp434p211 (interval) are indicated (blue line). A putative unequal crossover occurred between Alu C1 and Alu C2 in duplicated copies of GGT and DKFZp434p211, resulting in the fusion product shown. Sequences upstream and including Alu C2 in the fusion product were present in the GGT substrate, and sequences distal to the Alu were present in the DKFZp434p211 substrate.

As with USP18, we used BLAT and the UCSC browser to examine the sequences between the exons of GGT that became duplicated. Figure 4B shows how the second exon and surrounding intron of IGSF3, whose functional ancestral locus is on chromosome 1p13.1 (orange bar, Fig. 4B), was copied to GGT on 22q11.2 (yellow bar, Fig. 4B).

The evidence for the rearrangement between GGT and IGSF3 derived from examining the breakpoints and junctions for the rearrangements. As before, an Alu element was at the breakpoint and junction of this duplication event. The sequences including and proximal (left) to the Alu Sq in LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (B2a1 and B2a1) derive from the GGT locus in LCR22-8 (Alu B2), whereas sequences immediately distal (right) are from the IGSF3 locus on chromosome 1 (Fig. 4B). The rearrangement was likely mediated by a recombination event between two Alu elements, Alu B1 and Alu B2. We found that there was a breakpoint not in the middle of the Alu element, but at the end (vertical black bar, Fig. 4B). Thus, the Alu B1 in IGSF3 on chromosome 1p13.1 does not have any clear similarity to the products (B2a1, LCR22-2 and B2a2, LCR22-4). A BLAT search confirmed that B2, B2a1 (LCR22-2), and B2a2 (LCR22-4) are nearly identical and are not likely independent insertions (Suppl. Fig. 4).

A different breakpoint in the GGT gene occurred to create the copies in LCR22-5, LCR22-7, and LCR20 (Fig. 4C). The breakpoint occurred in the vicinity of Alu elements. Alu C1 is at the breakpoint of GGT in LCR22-8 and Alu C2 in the DKFZp434p211 locus in another LCR22 (Fig. 4C). Again, the breakpoint was at the end of the Alu C2 (vertical black bar, Fig. 4C; Suppl. Fig. 5).

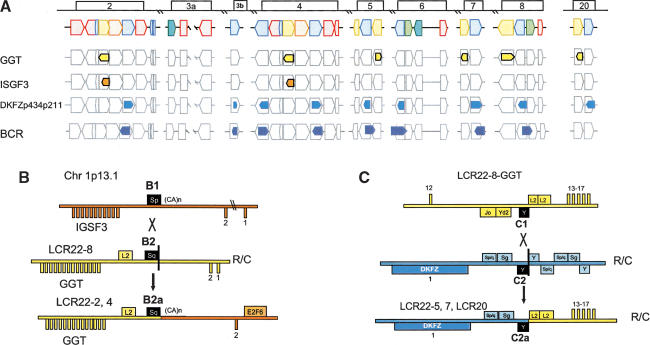

These events are illustrated more concisely in Figure 5A to determine whether the breakpoint junctions were junctions between modules comprising the LCR22s. Alu B1 is within IGSF3 on chromosome 1p13.1, and Alu B2 is present within the GGT locus in LCR22-8. The duplicated copies of B2, Alus B2a1 and B2a1, are at the junction between blocks comprising LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 (Fig. 5A). Alu C2 and duplicated copies of Alu C2 are at the junctions between blocks in three LCR22s, implicating these elements in shaping the genome architecture of LCR22s and one LCR that has migrated to chromosome 20 (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B shows the position of Alus B1 and C1 with respect to the genomic organization of GGT. Figure 5C illustrates the organization of the Alu substrates and products and demonstrates that they are largely unrearranged.

Figure 5.

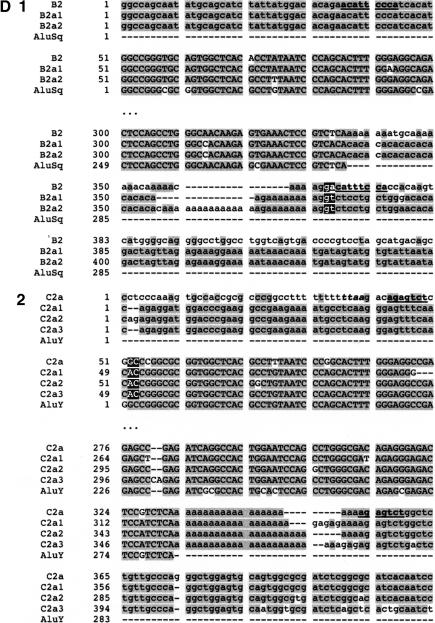

(A) Position of Alu elements involved in shaping GGT in the LCR22s. The GGT gene (yellow shapes; exonic orientation shown), IGSF3 (orange shapes), and DKFZp434p211 (blue shapes) within the block structure of the LCR22s are shown. Alu elements B1 (light gray), B2 (charcoal gray), C1 (light gray), and C2 (white) are illustrated in the “+” or “-” orientation. The duplicated copies of the Alu elements within their respective copies of GGT are illustrated. (B) Alus involved in breakpoints with respect to the genomic organization of GGT. The genomic organization of GGT was determined by comparing the cDNA sequence with the human genomic sequence by BLAST analysis. The position of Alus B1 and C1 with respect to the genomic organization of GGT is illustrated (dotted line). (C) Structure of Alu elements B2 and C2, including their duplicated copies. Each Alu monomer (red, pink) is illustrated on either side of the A-rich spacer (blue). The 3′ poly A tail is shown (black). Alu B2 and its copies are part of the Alu Sq subfamily (see Suppl. Fig. 4). Alu C2 and its copies are part of the Alu Y subfamily (see Suppl. Fig. 5). (D) Breakpoints within Alu targets. Alu repeats are shown in uppercase and flanking sequences in lowercase. The expected breakpoint positions are marked in red. Potential target site duplications are marked in boldfaced and underlined. (D1) Breakpoint within 3′ Alu target of Alu B2. The 5′ flanks of the Alu B2 substrate and its products B2a1, B2a2 are homologous, but this is not true of the 3′ flanks. The end of homology between Alu B2 and substrates corresponds to the position of the breakpoint. Alus B2a1 and B2a2 contain a variable (CA)n microsatellite within poly A tails, so it is difficult to mark the exact position. However, the presence of two Gs immediately flanking the poly A tail in both the substrate and products suggests the likely position of the breakpoint. During L1 endonuclease-mediated integration, the target sequence is duplicated at the 3′ end, except for the first two nucleotides. The position of the presumed breakpoint (GA) corresponds to start of the (partially preserved) 3′ Alu target-site duplication, i.e., 3′ duplicated target of the Alu insertion. Thus the recombination breakpoint coincides with the L1 endonuclease target site, which can be attacked by the L1 endonuclease. (D2) Breakpoint within 5′ target of Alu C2. The 3′ flanks of the Alu C2 and products C2a1, C2a2, C2a3 are homologous, but this is not true of the 5′ flanks; the end of homology between C2 and substrates, corresponds to the position of the breakpoint. The highlighted TTAA motif (yellow) corresponds to the putative original target; the first DNA nick probably occurred between TT and AA, 13 bp upstream of Alu C2a. The breakpoint within products is located 15 bp downstream of the expected first nick, perfectly fitting with the L1 endonuclease preference for second nick 15-16 bp downstream of the first one (Jurka 1997). Thus the breakpoint could be initiated by L1 endonuclease revisiting the original Alu target, and later repaired by homologous recombination. The second DNA nick probably occurred 2 bp downstream compared to the original insertion, and thus the first two nucleotides were not carried during the recombination event. See more details in Figure 9.

The precise positions of the breakpoints in Alus B2 and C2 are shown in Figure 5D (Suppl. Figs. 4,5). In the case of Alu B2, the breakpoint occurred within the 3′ Alu target site for its integration. The end of homology between the Alu B2 and B2a1 and B2a2 products corresponds to the position of the breakpoint. The presence of two Gs immediately flanking the polyA tail of Alu element in both the substrate and products delineates the position of the breakpoint. The position of the presumed breakpoint (GA; red in Fig. 5D1) corresponds to start of the (partially preserved) 3′ target-site duplication after Alu insertion, that is, 3′ duplicated target, corresponding with the L1 endonuclease target site (Fig. 5D).

A similar situation occurred for Alu C2. The breakpoint occurred in the 5′ target site of this Alu element (Fig. 5D2). The highlighted TTAA motif (yellow) corresponds to the putative original Alu target site; the first DNA nick by L1 endonuclease probably occurred between TT and AA, 13 bp upstream of Alu C2a copy (Fig. 5D2). The breakpoint within the Alu products C2a1, C2a2, and C2a3 is located 15 bp downstream the expected first nick (red), perfectly fitting with the preference of L1 endonuclease for a second nick, 15-16 bp downstream of the first one (Jurka 1997). Thus the position of the breakpoint coincides with the initial target for L1-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage and Alu integration (Jurka 1997). The same target if revisited by the L1 endonuclease can trigger recombination of the adjacent Alu element. This fits a model of L1 endonuclease involvement in both the initial Alu integration and subsequent recombination. The second DNA nick probably occurred 2 bp downstream compared to the original insertion, and thus the first two nucleotides were not carried during the recombination event.

In addition to the 5′ breakpoints in GGT, we were interested in whether Alu elements were present at the 3′ breakpoints in GGT. We examined the other side of GGT, 3′ to the last exon (end in chromosome 21721087) and found an Alu element at the breakpoint (5′ side of Alu Yd2, 21748855-21749005, minus orientation) between the blocks.

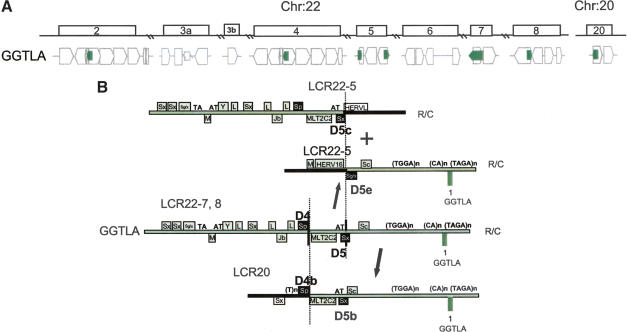

Duplication of GGTLA

We then examined the duplication events for GGTLA (Heisterkamp et al. 1991) mapping to LCR22-7 (Fig. 6A). As with USP18 and GGT, we examined the genes involved in the rearrangement events for GGTLA (Fig. 6A). GGTLA maps to LCR22-7, whereas duplicated truncated copies map to additional loci (Fig. 6A). In all cases, we found that the region surrounding exon 1 of GGTLA was involved in the rearrangement. We examined the sequences in the vicinity of exon 1 and its duplicated copies (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) Position of GGTLA within the block structure of the LCR22s. Each of the LCR22s is ordered with respect to the centromere of chromosome 22q11.2. The GGTLA (green) gene is shown in its proper transcription orientation. The functional GGTLA locus is in LCR22-7. (B) Recombination events for GGTLA in LCR22-7 to form products in LCR22-5 and LCR20. The different recombination events in the different Alu elements shaping LCR22-5 (19661038-19665200, top; 19692592-19699596) and LCR20 (chr 20:23944266-23949403) are shown. Examination of the GGTLA intron 1 in LCR22-7 revealed duplicated copies on LCR22-8 (unrearranged), LCR22-5, and LCR20. We found rearrangements in LCR22-5 and LCR20. For LCR22-5, a single breakpoint within Alu D5 was responsible for creating the two reciprocal copies, one in the proximal end of LCR22-5 and one at the distal end of LCR22-5. Both form the borders of the LCR22. A different breakpoint, in Alu D4, was responsible for shaping the border of LCR20.

The GGTLA locus between exons 1 and 2 contains two Alu elements, which mediate rearrangements, termed Alu D4 and D5 (black-filled boxes; Figs. 6B, 7A,B). We found that there was a split in the sequence of the GGTLA locus within the first intron, one half creating the proximal end of LCR22-5 and one half creating the distal end of LCR22-5 (Figs. 6A,B, 7A). This event was important in shaping the structure of this LCR22. The data are consistent with a single breakpoint in one Alu, Alu D5, creating reciprocal copies of the GGTLA locus (Fig. 7C; Suppl. Fig. 7). The copies of Alu D5 in the two duplicated products in LCR22-5 are termed Alu D5c and D5e (Fig. 7A). Sequences proximal (left) to Alu D5c and the distal monomer of this Alu are present in the proximal end of LCR22-5, whereas sequences on the 3′ side of the Alu are missing from LCR22-5 and represent non-LCR22 sequences (black bar, Fig. 6B). For the distal part of LCR22-5, sequences proximal (left) to Alu D5e and comprising the first monomer of Alu D5 are non-LCR22 sequences, whereas sequences distal to the Alu D5e are similar to LCR22-7 sequences.

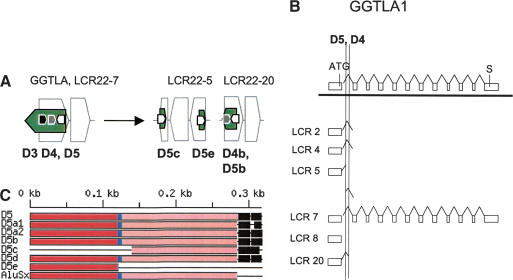

Figure 7.

(A) Position of Alu elements involved in GGTLA rearrangements. The GGTLA gene (green shapes; exonic orientation shown) within the block structure of the LCR22s is shown. Alu elements D4 (gray) and D5 (white) are illustrated in the “+” or “-” orientation, associated with their GGTLA and gene copies. (B) Alus involved in breakpoints with respect to the genomic organization of GGTLA. The genomic organization of GGTLA was determined by comparing the cDNA sequence with the human genomic sequence by BLAST analysis. The position of Alus D4 and D5 with respect to the genomic organization of GGTLA is illustrated (dotted line). (C) Structure of Alu element D5 including its duplicated copies. A breakpoint in Alu D5 resulted in two reciprocal copies, D5c and D5e. For more details, see Supplemental Figure 7.

A rearrangement mediated by a different Alu element was involved in forming the copy of GGTLA on chromosome 20 (Fig. 6B). Again, the breakpoint junction formed the border of this LCR, suggesting that this rearrangement had a role in shaping the LCR20 structure itself (Fig. 7A). A breakpoint at the 3′ end of Alu D4 in LCR22-7 was responsible for shaping LCR20. The sequence data suggest that an L1 endonuclease-mediated mechanism similar to that which occurred for Alu B2 and Alu C2 might have taken place for Alu D4 and its duplicated copies (Suppl. Fig. 6). Alu D4b is retained in chromosome 20, whereas sequences proximal are non-LCR22 sequences and sequences distal are LCR22 sequences. We examined the other side of the breakpoint upstream of the first exon of GGTLA. We found that breakpoints occurred on either side of an Alu Y (21342706-21343001). Thus, Alu elements were responsible for breakpoints on both sides of the GGTLA gene duplications.

DISCUSSION

Segmental Duplication as a Model for Gene Rearrangements

Segmental duplications or LCRs have over 95% sequence identity, suggesting that they have evolved over the last 35 million years (Bailey et al. 2002b). FISH-mapping studies of metaphase chromosomes from apes and monkeys using 22q11.2 probes confirmed the presence of multiple copies in primate lineages (Shaikh et al. 2000; Bailey et al. 2002b). Thus, they have been quite active during primate speciation. As LCRs comprise 5% of the human genome (Bailey et al. 2002a) and many are associated with human disorders, we examined the LCRs on 22q11.2 to identify sequence relationships that could shed light on the mechanism(s) of duplications and chromosome rearrangements. By comparing copies of LCR22s with each other, we traced changes that have occurred during evolution. We found that the LCR22s are heavily rearranged. In most regions within the LCR22s, it was difficult to infer the ancestral state or trace the evolutionary processes that shaped them, with the exception of the known genes and truncated pseudogene copies within them. It was possible to do this because functional genes are under selective pressure against exon reshuffling; therefore, they serve as good estimators of the ancestral state of the loci. Duplicated copies of the genes are relatively unconstrained, and they can form unprocessed pseudogenes in which steps of their evolution can be traced compared to the ancestral copy. LCR genes therefore serve as a good model for gene rearrangements; analogous changes in genes would lead to loss of gene function and likely to genetic disorders and would be eliminated during evolution.

Alu-Mediated Rearrangements Shape Pseudogenes on 22q11.2

In this report we present evidence for Alu-mediated rearrangements in shaping three known genes within LCR22s—USP18, GGT, and GGTLA—and part of the BCR/DKFZp434p211 complex. We found that four Alu elements (A1, A2, A3, and A4) were present at the breakpoints in the ancestral USP18 locus and in the copies of USP18 in three LCR22s: LCR22-2, -3a, and -4. In the case of two of them, A3 and A4, we found evidence of unequal crossover mechanisms between Alu elements likely responsible for the rearrangements. When we examined the duplication events of the GGT gene, we found that there were two independent breakpoints in this gene, one between exons 2 and 3 and another between exons 12 and 13. We found evidence of homology-directed misalignment, but a different mechanism was responsible for mediating the rearrangement. The breakpoints in the Alu elements involved in the rearrangements occurred not in the middle of Alu elements, as above for USP18, but at the end of Alu elements. Of further interest, one of the two genes involved in shaping the LCR22s, IGSF3, maps to 1p13.1 and is therefore in trans to GGT on 22q11.2.

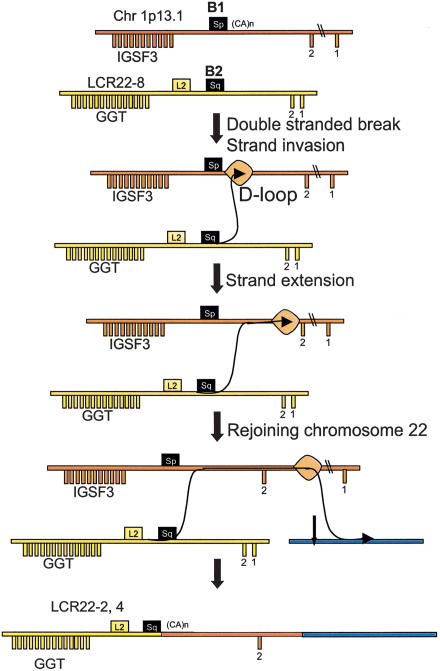

In this case, we propose that a copy of IGSF3 and a copy of GGT were involved in an event that is analogous to the one described by Richardson et al. (1998). Figure 8 shows the model we propose for the interchromosomal recombination between IGSF3 and GGT resulting in a chimeric fusion product. Homologous recombination (HR) is highest between repeats located on the same chromosome; however, recombination is also known to exist between nonhomologous chromosomes, suggesting that mammalian genomes have a mechanism scanning the entire genome (Baker et al. 1996; Richardson et al. 1998). Rearrangements induced by a double-stranded break (DSB) in cell culture preferentially lead to gene conversions, but transferral of larger DNA segments from an unbroken chromosome to broken ones has occasionally been detected (Fig. 8; Richardson et al. 1998). If this is the case, we believe that the IGSF3-GGT fusion was created in meiosis by a replication-dependent mechanism similar to the one proposed by Richardson et al. (1998). This is because in both cases, a transfer of a long DNA segment from chromosome 1 to chromosome 22 occurred without an apparent chromosomal aberration (translocation). The only difference is that in the present case, there was no selection mechanism to retain homologous sequences after rejoining on chromosome 22 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A model of insertion of IGSF3 into LCR22-2 and LCR22-4; interchromosomal recombination between IGSF3 on chromosome 1 and GGT on chromosome 22 (see Fig. 6 in Richardson et al. 1998), explaining the mechanism by which recombination occurs on nonhomologous chromosomes, thereby avoiding crossovers which would lead to aberrant translocations. In this model, a breakpoint in chromosome 22 occurred, presumably at one end of misaligned Alu elements (black boxes). The broken ends from chromosome 22 then would invade the homologous sequence, the Alu (black box) on chromosome 1, forming a D-loop. The invading end would prime DNA synthesis, extending, in this case, a significant distance on chromosome 1. The process would involve the migration of the D-loop into nonhomologous sequences downstream of the region of homology (the Alu). At a further distance, the newly synthesized strand would rejoin chromosome 22 in a region of homology (or nonhomology) between chromosomes 1 and 22. Thus, this model combines homologous recombination in the absence of a crossover with nonhomologous repair. It was proposed for mitotic rearrangements (Richardson et al. 1998), but could be envisioned for meiotic rearrangements as well.

High-Copy Repetitive Elements in Modifying Genome Architecture

In our analysis we detected apparent Alu-mediated rearrangements in LCR22 genes, thereby shaping their architecture during evolution. There are several potential factors regarding the reason(s) why Alu elements are more likely to stimulate duplications and rearrangements in gene-richregions compared to other repeats, including age, copy number, genomic distribution, and structure. HR depends on the degree of similarity between two substrates. Young transposable elements (TEs) including primate-specific Alu are relatively similar to one another, due to the low number of base substitutions, and are more likely to stimulate HR.

The location and high copy number of Alus make them a good substrate for recombination. Alus are the most widespread class of TEs, with about one million copies in the genome (Lander et al. 2001). LINEs (L1) are present in about 500,000 copies; LTR-retrotransposons, such as endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), are present in 440,000 copies (Lander et al. 2001). However, HERVs families are often very diverse and are present in low copy numbers (Repbase Update, Jurka 2000). Therefore, the mean distance between two similar HERV copies can be very large, meaning that they are not good substrates for recombination. Moreover, whereas Alu elements are more frequent in GC- and gene-rich DNA, LINEs and the majority of HERV families are underrepresented there (Lander et al. 2001; Paces et al. 2002).

Structural reasons also result in Alu SINEs being good candidates for recombination. The Alu genome structure is similar between families, and due to their short size, Alus often escape 5′ truncation typical for LINEs. Most HERVs are structurally rearranged, and about 85% of them are solo LTRs (Lander et al. 2001), products of LTR-LTR recombination (Mager and Goodchild 1989; Lander et al. 2001). In the case of LINEs, most are 5′-truncated (Voliva et al. 1983; Lander et al. 2001), containing only the 3′ terminal part, which is very different between L1 families (Smit et al. 1995; Jurka 2000). Like endogenous retroviruses, there are not many closely spaced, highly similar L1 elements prone to recombination. However, Alu repeats are ∼280 bp long, which seems to be sufficient for effective homologous recombination in mammalian cells (Rubnitz and Subramani 1984; Liskay et al. 1987; Waldman and Liskay 1988).

Indeed, the majority of human genetic disorders caused by homologous recombination between repetitive sequences are Alu-Alu recombinations (Deininger and Batzer 1999; Batzer and Deininger 2002; Kolomietz et al. 2002). When Deininger and Batzer reviewed such genetic disorders in 1999, they collected 49 cases of both somatic and germline events linked to Alu rearrangements, whereas there were only two cases of homologous recombination between L1 copies related to human diseases. There are examples of recombinations of other repetitive elements, such as HERV-mediated duplications of the AZFa region on the human Y chromosome compatible with male fertility (Bosch and Jobling 2003), but these are rare.

Mechanism of Alu-Mediated Rearrangements

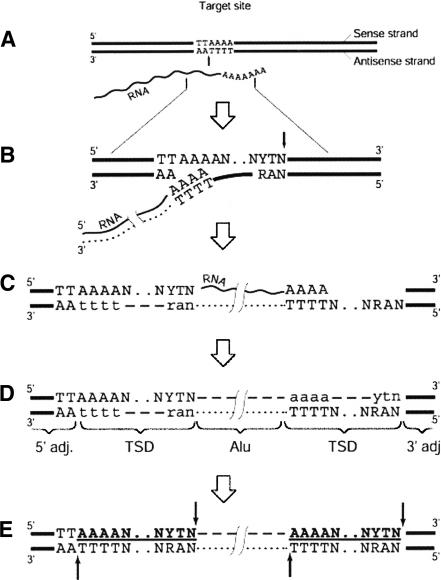

As described above, homology between Alu elements is likely responsible for misalignment of chromosomes during meiosis. In some of the cases, unequal crossovers were responsible for mediating the rearrangement and in others, the breakpoints were at the ends of Alu elements. In this context it should be noted that Alu elements are flanked by retrotransposon target-site duplications (TSDs) containing TTTTAA-like sequence motifs (Jurka 1997). A possible stimulus for these may derive from revisiting the same targets by the L1-encoded endonuclease capable of nicking specific DNA targets (Feng et al. 1996), leading to recombinogenic single- or even double-strand breaks (Fig. 9). In fact, Alu elements are substrates for L1-mediated retrotransposition (Cost et al. 2002).

Figure 9.

Model of Alu integration and generation of breakpoint near integrated Alu. This is based upon the B2, C2, and D4 rearrangements. (A) Enzymatic nicking in the presence of RNA indicated by vertical black arrow. (B) Synthesis of cDNA, indicated by dotted line, and formation of a second nick, indicated by black arrow on the opposite strand. (C) Completion of reverse transcription and DNA-dependent DNA synthesis, indicated by a dashed line and the lowercase letters, followed by ligation. (D) Elimination of RNA and synthesis of the second DNA strand. The integrated Alu element is surrounded by the target-site duplications (TSDs), usually 15-16-bp long. TSDs are marked in boldface and underlined. (E) Potential sites for secondary attacks by the L1 endonuclease, in 5′ and 3′ duplicated targets, are indicated by the black arrows. The 5′ flanking sequence contains an intact target TTAAAAN.NYTN; the 3′ duplicated target lacks the first two nucleotides (typically TT). Modified from Jurka (1997).

Our hypothesis about the revisiting of Alu targets by L1 endonuclease, shown as a model in Figure 9, may explain the occurrence of full-length Alu elements within the breakpoints of LCR22 rearrangements. The Alu target sequence is located at the 5′ end of Alu insertions (targets are also partially duplicated on 3′ flanks). Additional cleavage of the target by L1 endonuclease would preferentially occur at the targets located at the 5′ and 3′ flanks, but not inside, Alu insertions. Therefore, the L1 endonuclease may be viewed as an additional enzyme capable of inducing DNA breaks, thus inducing genomic instabilities. The utilization of L1 endonuclease in Alu mobilization has been directly demonstrated in vitro (Cost et al. 2002), supporting our hypothesis.

In addition to its role as a target site, the TTTTAA-like sequences also harbor potentially kinkable DNA sites (Jurka et al. 1998). Suchmotifs are associated with rearrangements of dispersed elements in pericentromeric α-satellites (Mashkova et al. 2001). Such kinkable sites associated with TSDs may therefore also represent focal points for recombination, as observed in humans and other organisms (Mashkova et al. 2001).

LCR22 Blocks and Alu Elements

In this study, we obtained many pieces of sequence evidence implicating Alu elements in the shuffling of LCR22 genes and their duplicated copies, suggesting that this is not a random event. Besides the shuffling of exons, some of the Alu elements coincided with the positions of several junctions between LCR22 blocks or between LCR22 and non-LCR22 sequences, implicating them in shaping the LCR22 blocks themselves. On the other hand, some of the Alus involved in the rearrangements we describe were present in the middle of LCR22 blocks, suggesting that different, non-Alu-mediated mechanisms were responsible for duplicating or shaping those blocks. It is not surprising that several mechanisms could shape the architecture of the human genome. In fact, some borders of LCR22 blocks or the junction between LCR22 sequences and non-LCR22 sequences did not harbor Alu elements. To be more precise, Alus were at all the borders for USP18, GGT, and GGTLA, but they were at only one border for BCR. However, multiple evolutionary steps might be masked when only human sequence is examined. This is because the original breakpoints and junctions may have already been lost during primate speciation. Another feature is the complex nature of the LCR22s, genes, pseudogenes, and predicted genes. This is particularly true for BCR and the predicted gene DKFZp434p211, which are intertwined (Bailey et al. 2002b). As mentioned, we did not detect Alus at the 5′ truncation breakpoints for BCR, but we did find them at the 3′ truncations. This suggests either multiple mechanisms or that some of the original rearrangement endpoints have been lost. Nonetheless, we believe that Alu-mediated rearrangements have shaped a significant portion of the genome architecture of LCRs during evolution, but that it may be necessary to examine nonhuman primate species to trace all of the steps.

Summary

The ability to trace the products of recombination within the sequence of the human genome has provided us with a unique opportunity to identify the mechanisms responsible for shaping the architecture of the human genome, particularly segmental duplications, large deletions, and interchromosomal recombination during evolution. The availability of individuals with chromosome rearrangement disorders provides an additional opportunity to understand recombination mechanisms in a single meiosis. It is possible that some of the same mechanisms are responsible for both types of events.

METHODS

Identification of LCR22-2 and LCR22-4

We previously generated physical maps of LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 and constructed a minimal tiling path of genomic clones across each LCR [LCR22-2, AC008079 (BAC 519D21), AC008132 (PAC 99506), and AC008103 (PAC 699J1)]; [LCR22-4, AC008018 (BAC 379N11), AC009288 (PAC 413M7) Dunham et al. 1999; Edelmann et al. 1999a]. We compiled the sequences of the LCR22-2 and the LCR22-4 clones in the UCSC browser into two separate contigs, termed LCR22-2 and LCR22-4. We then removed the high-copy repetitive elements in each contig, using Repeat-Masker (http://woody.embl-heidelberg.de/repeatmask/). We then used the two contigs as a reference to identify other LCR22 sequences among the clones that comprise the minimal tiling path across chromosome 22q11.2 from 14.9-22.6 Mb, using miropeats software (Parsons 1995; http://www.genome.ou.edu/). We chose the clones from those assembled in the UCSC browser [June 2002 assembly (hg11) of the April 2002 sequence freeze].

Identification of LCR22 Genes

We first performed a MegaBLAST analysis (Altschul et al. 1990; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) on the LCR22 sequences to identify genes and pseudogenes that might lie within them. Next, we performed a BLASTnr analysis using the known genes or gene fragments that map to the LCR22s. We compared this analysis to recent annotations of the chromosome 22 genes and pseudogenes (Bailey et al. 2002b; Collins et al. 2003). To define the genomic organization of the genes, we subjected the cDNA for USP18 (GenBank acc. NM_017414), E2F6 (GenBank acc. NM_001952), BCR (GenBank acc. NM_004327), DKFZp434p211 (GenBank acc. NM_014549), GGTLA (GenBank acc. NM_004121), GGT (GenBank acc. J04131), and IGSF3 (GenBank acc. NM_001542) to a BLAST 2 sequences analysis (Tatusova and Madden 1999) with each of the LCR22 clones. We compared the genomic organization to that in the public browsers (Ensemble; http://www.ensembl.org/; UCSC browser).

Identification of LCR22 Breakpoint Junctions

To identify the LCR22 breakpoint junctions containing the substrates and products of recombination, we used the UCSC browser (June 2002 assembly) to identify the functional loci of the genes. The USP18 gene maps to positions 15573184-15600410 (size, 27,227 bp) on chromosome 22; GGT is at 21695307-21721084 (size, 25,778 bp); GGTLA is at 21311766-21337166 (size, 25,401 bp), and BCR is at 20221386-20356809 (size, 135,424 bp). BLAT analysis pinpointed the intervals harboring the breakpoints at the site of transposition (Kent 2002). We then integrated the architectural features (genes, pseudogenes, predicted genes, high-copy repeated elements, and simple sequence repeats) from the UCSC browser tracks with respect to the position of the breakpoints in the substrates of recombination and the breakpoint junction in the products of recombination.

Northern Blot Hybridization

We generated probes by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and purified them with Qiaquick Gel Extraction (QIAGEN). The following primer pairs were used for PCR amplification: BCR F (5′-3′) TGACTGACAGCTGGTCCTTG, BCR R TCAGGCCTGGACTC TGAGA, GGT1 F ATTTATTGTGCTGCTCTGCTG, GGT1 R GCAAGCCATCGTCCGCAC, GGTLA1 F TCGATCCATCTTCGTGTCTG, GGTLA1 R GGTGTCGAGAGAGGACCACA, USP18 F TCATTTTCCATTTCCGTTCC, and USP18 R AAATACCCCCTGCCACTGAC. We labeled the probes with α32P-dCTP through random priming using Rediprime II (Amersham) and column cleaned them. The Northern Blots (Clontech; MTN1 blots) were prehybridized for 1 h at 42°C in UltraHyb solution (Ambion) and hybridized overnight at 42°C in the same solution. We washed the filters twice with 2x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at room temperature, twice with 1x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at room temperature, and twice with 0.1x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at 42°C. The only exception to these washes was for the GGTLA1 blot, which we washed twice with 2x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at room temperature, twice with 1x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at 42°C, and twice with 0.1x SSC 0.1% SDS for 20 min at 65°C. The filters were exposed to Kodak Ultrasensitive film X-OMAT AR for 1-3 d (6 h-overnight) at -80°C with intensifying screens.

Low-Stringency Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

We cultured the lymphoblastoid cell lines according to standard cytogenetic laboratory procedures and prepared slides with metaphase chromosomes. We chose BAC clones AC008132 and AC009288 because they contain LCR22-2 and LCR22-4 sequences, respectively. We isolated the DNA by a standard lysis by alkali procedure, and we labeled probes adjacent to the low-copy repeats with digoxigenin by nick-translation. Probes labeled in biotin were used as a control for hybridization- and identification-specific chromosomes. We then performed FISH as described (Shaffer et al. 1997). We viewed cells with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope equipped with a triple-band pass filter that allows multiple colors to be visualized simultaneously. We captured and stored digital images using a MacProbe 4.3/Power Macintosh G4 system (Applied Imaging) and printed images using a Tektronix Phasar 750.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Gary Swergold, John Greally, and Jack Lenz for providing insight into the models for Alu-mediated recombination. We appreciate the efforts of Aaron Theisen, Washington State University for his careful editing of the manuscript. This work is supported by the MOD (1-FY00-768; B.E.M.) and NIH (1 PO-1 HD 39420-01; B.E.M. and L.G.S.; and 5 P01 HD34980-05; B.E.M.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.1549503.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol 215: 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.A., Gu, Z., Clark, R.A., Reinert, K., Samonte, R.V., Schwartz, S., Adams, M.D., Myers, E.W., Li, P.W., and Eichler, E.E. 2002a. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 297: 1003-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.A., Yavor, A.M., Viggiano, L., Misceo, D., Horvath, J.E., Archidiacono, N., Schwartz, S., Rocchi, M., and Eichler, E.E. 2002b. Human-specific duplication and mosaic transcripts: The recent paralogous structure of chromosome 22. Am. J. Hum. Genet 70: 83-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.D., Read, L.R., Beatty, B.G., and Ng, P. 1996. Requirements for ectopic homologous recombination in mammalian somatic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 7122-7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batzer, M.A. and Deininger, P.L. 2002. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, E. and Jobling, M.A. 2003. Duplications of the AZFa region of the human Y chromosome are mediated by homologous recombination between HERVs and are compatible with male fertility. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12: 341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, V.G., Nowak, N., Jang, W., Kirsch, I.R., Zhao, S., Chen, X.N., Furey, T.S., Kim, U.J., Kuo, W.L., Olivier, M., et al. 2001. Integration of cytogenetic landmarks into the draft sequence of the human genome. Nature 409: 953-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.E., Goward, M.E., Cole, C.G., Smink, L.J., Huckle, E.J., Knowles, S., Bye, J.M., Beare, D.M., and Dunham, I. 2003. ReevAluating human gene annotation: A second-generation analysis of chromosome 22. Genome Res. 13: 27-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost G.J., Feng Q., Jacquier A., and Boeke J.D. 2002. Human L1 element target-primed reverse transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 21: 5899-5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courseaux, A., Richard, F., Grosgeorge, J., Ortola, C., Viale, A., Turc-Carel, C., Dutrillaux, B., Gaudray, P., and Nahon, J.L. 2003. Segmental duplications in euchromatic regions of human chromosome 5: A source of evolutionary instability and transcriptional innovation. Genome Res. 13: 369-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, P.L. and Batzer, M.A. 1999. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 67: 183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, C., Biro, P.A., Choudary, P.V., Elder, J.T., Wang, R.R., Forget, B.G., de Riel, J.K., and Wiessman, S.M. 1979. RNA polymerase III transcriptional units are interspersed among human non-α-globin genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 76: 5095-5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, I., Shimizu, N., Roe, B.A., Chissoe, S., Hunt, A.R., Collins, J.E., Bruskiewich, R., Beare, D.M., Clamp, M., Smink, L.J., et al. 1999. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature 402: 489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann, L., Pandita, R.K., and Morrow, B.E. 1999a. Low-copy repeats mediate the common 3-Mb deletion in patients with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64: 1076-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann, L., Pandita, R.K., Spiteri, E., Funke, B., Goldberg, R., Palanisamy, N., Chaganti, R.S., Magenis, E., Shprintzen, R.J., and Morrow, B.E. 1999b. A common molecular basis for rearrangement disorders on chromosome 22q11. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8: 1157-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q., Moran, J.V., Kazazian Jr., H.H., and Boeke, J.D. 1996. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell 87: 905-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisterkamp, N. and Groffen, J. 1988. Duplication of the BCR and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 16: 8045-8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisterkamp, N., Stam, K., Groffen, J., de Klein, A., and Grosveld, G. 1985. Structural organization of the BCR gene and its role in the Ph′ translocation. Nature 315: 758-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisterkamp, N., Rajpert-De Meyts, E., Uribe, L., Forman, H.J., and Groffen, J. 1991. Identification of a human γ-glutamyl cleaving enzyme related to, but distinct from, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88: 6303-6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J. 1997. Sequence patterns indicate an enzymatic involvement in integration of mammalian retroposons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 1872-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J. 2000. Repbase update: A database and an electronic journal of repetitive elements. Trends Genet. 16: 418-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J. and Pethiyagoda, C. 1995. Simple repetitive DNA sequences from primates: Compilation and analysis. J. Mol. Evol. 40: 120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J., Klonowski, P., and Trifonov, E.N. 1998. Mammalian retroposons integrate at kinkable DNA sites. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 15: 717-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W.J. 2002. BLAT—The BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12: 656-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolomietz, E., Meyn, M.S., Pandita, A., and Squire, J.A. 2002. The role of Alu repeat clusters as mediators of recurrent chromosomal aberrations in tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 35: 97-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Linton, L.M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M.C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., et al. 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409: 860-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liskay, R.M., Letsou, A., and Stachelek, J.L. 1987. Homology requirement for efficient gene conversion between duplicated chromosomal sequences in mammalian cells. Genetics 115: 161-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager, D.L. and Goodchild, N.L. 1989. Homologous recombination between the LTRs of a human retrovirus-like element causes a 5-kb deletion in two siblings. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 45: 848-854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkova, T.D., Oparina, N.Y., Lacroix, M.H., Fedorova, L.I., Tumeneva, I.G., Zinovieva, O.L., and Kisselev, L.L. 2001. Structural rearrangements and insertions of dispersed elements in pericentromeric α satellites occur preferably at kinkable DNA sites. J. Mol. Biol. 305: 33-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C., Courtay, C., Geurts van Kessel, A., ten Hoeve, J., Heisterkamp, N., and Groffen, J. 1993. Localization of a γ-glutamyl-transferase-related gene family on chromosome 22. Hum. Genet. 91: 31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paces, J., Pavlicek, A., and Paces, V. 2002. HERVd: Database of human endogenous retroviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 205-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J.D. 1995. Miropeats: Graphical DNA sequence comparisons. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 11: 615-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potocki, L., Chen, K.S., Park, S.S., Osterholm, D.E., Withers, M.A., Kimonis, V., Summers, A.M., Meschino, W.S., Anyane-Yeboa, K., Kashork, C.D., et al. 2000. Molecular mechanism for duplication 17p11.2—The homologous recombination reciprocal of the Smith-Magenis microdeletion. Nat. Genet. 24: 84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajpert-De Meyts, E., Heisterkamp, N., and Groffen, J. 1988. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of human γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85: 8840-8844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C., Moynahan, M.E., and Jasin M. 1998. Double-strand break repair by interchromosomal recombination: Suppression of chromosomal translocations. Genes & Dev. 12: 3831-3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubnitz, J. and Subramani, S. 1984. The minimum amount of homology required for homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4: 2253-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer, H., Liu, L.Q., Zhou, L., Little, M.T., Pan, Z., Hetherington, C.J., and Zhang, D.E. 2000. Cloning and characterization of a novel human ubiquitin-specific protease, a homologue of murine UBP43 (USP18). Genomics 65: 44-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, L.G., Kennedy, G.M., Spikes, A.S., and Lupski, J.R. 1997. Diagnosis of CMT1A duplications and HNPP deletions by interphase FISH: Implications for testing in the cytogenetics laboratory. Am. J. Med. Genet. 69: 325-331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, T.H., Kurahashi, H., Saitta, S.C., O'Hare, A.M., Hu, P., Roe, B.A., Driscoll, D.A., McDonald-McGinn, D.M., Zackai, E.H., Budarf, M.L., et al. 2000. Chromosome 22-specific low copy repeats and the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Genomic organization and deletion endpoint analysis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9: 489-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A.F., Toth, G., Riggs, A.D., and Jurka, J. 1995. Ancestral, mammalian-wide subfamilies of LINE-1 repetitive sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 246: 401-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz, P. and Lupski, J.R. 2002. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 18: 74-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova, T.A. and Madden, T.L. 1999. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174: 247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voliva, C.F., Jahn, C.L., Comer, M.B., Hutchison III, C.A., and Edgell, M.H. 1983. The L1Md long interspersed repeat family in the mouse: Almost all examples are truncated at one end. Nucleic Acids Res. 11: 8847-8859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, A.S. and Liskay, R.M. 1988. Dependence of intrachromosomal recombination in mammalian cells on uninterrupted homology. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8: 5350-5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackai, E.H. and Emanuel, B.S. 1980. Site-specific reciprocal translocation, t(11;22) (q23;q11), in several unrelated families with 3:1 meiotic disjunction. Am. J. Med. Genet. 7: 507-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]