Abstract

Background:

It has been proposed that hepatitis C virus (HCV) antigens are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and may contribute to severity of the disease. Increased expression of the apoptosis-regulating proteins p53 and tTG and decreased levels of bcl-2 in the keratinocytes of the skin of psoriatic patients have been reported.

Aim:

This study aims to identify the serum levels of apoptosis-regulating proteins in patients with psoriasis and without HCV infection and to study the relation between clinical severity of psoriasis and the presence of HCV infection.

Materials and Methods:

Disease severity was assessed by psoriasis area severity index score (PASI) of 90 patients with psoriasis grouped as mild (n = 30), moderate (n = 30) and severe (n = 30); 20 healthy individuals were used as controls. All groups were subjected for complete history taking, clinical examination, and tests for liver function and HCV infection. The serum levels of apoptosis related proteins: p53, tTG and bcl-2 were estimated by enzyme linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA).

Results:

There was a statistically significant (P < 0.001) correlation between clinical severity of psoriasis and presence of HCV antibodies and HCV-mRNA. In addition, significantly (P < 0.001) raised serum p53 and tTG, and reduced bcl-2 were observed among HCV-positive patients as compared to HCV-negative patients and control patients.

Conclusion:

These results conclude that clinical severity of psoriasis is affected by the presence of HCV antibodies and overexpression of apoptotic related proteins. In addition, altered serum levels of apoptosis-regulating proteins could be useful prognostic markers and therapeutic targets of psoriatic disease.

Keywords: Apoptosis, B cell lymphoma-2 protein, Hepatitis C virus, P53, Psoriasis, tissue transglutaminase

Introduction

What was known?

All previous researchers who studied the apoptosis markers in psoriasis have localized those markers in patients’ skin.

HCV is currently suspected as a possible pathogen in psoriasis.

Till date; there have been no studies on the importance of Bcl-2, P53, and tTG concentrations in the serum of patients with psoriasis. Also, no previous research has investigated the clinical severity of psoriasis in HCV infection, regarding changes in apoptosis and its regulatory proteins.

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease characterized by hyper proliferation of keratinocytes associated with acute and chronic inflammatory cells.[1,2]

Although there are varied etiological factors in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, recent data shows that hepatitis C virus (HCV) is more prevalent in patients with psoriasis than in the normal population.[3] HCV in particular is associated with many dermatoses including psoriasis. The extra-hepatic manifestations of HCV including cutaneous features have been extensively reviewed.[4] The association of viral hepatitis and psoriasis has been reported.[5,6] HCV is currently suspected as a possible pathogen in psoriasis.[7,8] On the other hand, recent study shows abnormalities in liver enzymes in 47% of acute generalized pustular patients with psoriasis.[9]

Apoptosis plays an important role in the elimination of unwanted cells during development and also as a factor that maintains proliferative homeostasis.[10] The marked thickening of the epidermis in psoriasis may be related to the imbalance of the homeostasis caused by abnormal apoptotic process.[11] Regulation of apoptosis is mediated by a set of proteins such as p53[12], bcl-2[13] and tTG.[14] Recent study reported significant overexpression of pro-apoptotic markers (Bax, Fas, P53, and Caspase-3) and no change in antiapoptotic marker Bcl-2 in skin samples of advanced HCV liver patients.[15] Bcl-2 is a proto-oncogene protecting the cells against apoptosis. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and Behçet disease[16] have been reported to have excessive expression of Bcl-2 in serum and lymphatic cells. Recently, only the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c as a marker of apoptosis mediated via oxidative stress was measured in the serum as sign of the pathogenesis of psoriasis.[17] Till date, there have been no studies on the importance of Bcl-2, P53 and tTg concentrations in the serum of patients with psoriasis. Also, no previous research has investigated the clinical severity of psoriasis in HCV infection, regarding changes in apoptosis and its regulatory proteins.

This study aimed to identify the serum levels of apoptosis-regulating proteins in patients with psoriasis and without HCV infection and to study the relation between clinical severity of psoriasis and the presence of HCV infection.

Materials and Methods

Patients

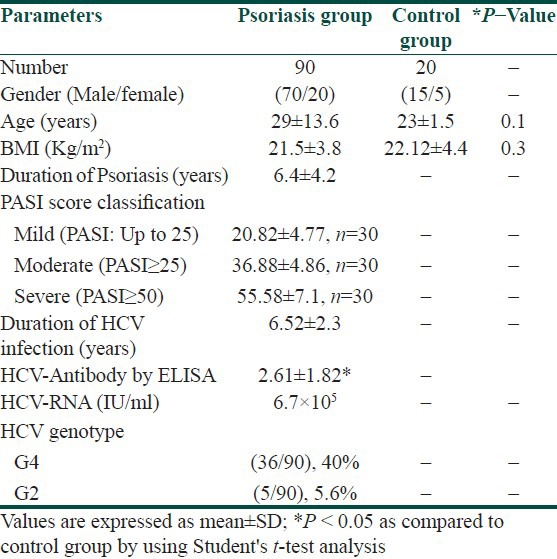

A total of 110 individuals were selected from patients admitted to the Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt. Out of these 20, age- and sex matched healthy individuals (15 men and 5 women, age range: 18-65 years) with a mean age of 23 ± 1.5 years were selected as controls who attended routine health check- ups at the hospital. Total 90 psoriatic patients (70 men and 20 women, age range: 18-64 years) with a mean age of 29 ± 13.6 years with proven viremia, HCVantibodies, HCV-RNA positivity, and genotype determinations were included in this study. Patients and control subjects who were alcoholics or smokers and had past or concurrent diseases like anemia, abnormal lipid profile, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, liver or kidney diseases, HIVand/or HBV co-infection, or other causes of chronic liver diseases and inflammatory skin diseases that may possibly affect the redox status were excluded from the study. Also subjects who were overweight and obese (body mass index, BMI ≥ 25 and ≥30 kg/m2) were excluded from the study. Psoriatic patients with any topical therapy within 4 weeks, systemic drug therapy or photo chemotherapy within 3 months were excluded from this study. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and was reviewed and approved by ethical committee of the Department of Dermatology. All subjects completed a structured questionnaire with questions regarding demographic data and daily medication use. The demographics and baseline characteristics of patients with psoriasis and controls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of psoriatic patients and healthy control groups (mean±SD)

Psoriasis area and severity index

The patients were diagnosed by Auspitz sign, clinical features of psoriasis like erythema, itching, thickening and scaling of skin. Disease duration of psoriatic patients ranges from 5 months to 10 years with a mean range of (6.4 ± 4.2 years). The clinical severity was determined according to the PASI.[18] PASI assesses four body regions: The head, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities. For each region, the surface area involved is graded from 0 to 6 and each of three parameters (erythema, thickness, and scaling of the plaques) is graded from 0 to 4. The scores from the regions were summed to give a PASI score ranging from 0 to 72. Psoriatic patients were classified into mild (30 patients; PASI up to 25), moderate (30 patients; PASI ≥ 25) and severe (30 patients; PASI ≥ −50). Peripheral venous blood samples were obtained from patients and controls in the morning following an overnight fast. Then, serum samples were aliquoted into smaller containers and stored at −80° C until assaying.

Blood analysis

Biochemical analysis

Test for serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were performed using Max Discovery™ Color Endpoint Assay kits (Cat. No.BO_ 5605-01 and BO_3460-08, Bioo Scientific Co., USA.).

Estimation of HCV antibodies using enzyme linkedimmunosorbent assay

Diagnosis of chronic HCV was established by elevated (ALT) levels in persons having HCV antibody (anti-HCV) by a third generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Axsym HCV 3.0, Abbott Laboratories, and Chicago, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo, USA). The HCV RNA was extracted by the silica method and PCR was performed as described by Boom et al.[19]

HCV quantitative test

HCV RNA quantification was done by using Smart Cycler II Real time PCR (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, Calif. USA) with HCV RNA quantification kits (Sacace Biotechnologies, Italy). HCV- RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

HCV genotyping

HCV genotyping technique was done for sera of HCV positivepatients using PCR technique. The method was done as described by Okamoto et al.[20]

Determination of apoptotic marker by ELISA

Serun anti-tissue transglutaminase (IgA) was determined using a commercially available, non-isotropic, anti-t-Tg IgA ELISA kit (Cat# 27-GD70; ALPCO Diagnostic, USA). Also, serum bcl-2 concentrations were determined using a commercially available, non-isotropic bcl-2 ELISA kit (Cat# QIA23, Oncogene Research Products, Germany). The quantification of p53 concentration in serum was determined using photometric one-step-enzyme-immunoassay ELISA kit (Cat. Nr. 11 828 789 001; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Roche Applied Science, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) program version 10 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The quantitative data were presented in the form of mean and standard deviation. Student's t-test was used to compare quantitative data of two groups. Correlations were analyzed by Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

A total of 90 patients (70 men, 20 women; age range: 18-64 years, mean age: 29 ± 13.6 years) with psoriasis were included in this study. Anti-HCV antibodies were detected in 45.6% (46/90) of the patients: The results were confirmed with the detection of HCV-RNA PCR test in serum samples. Based on genotype analysis of psoriatic patients infected with HCV, the most frequently detected genotype was 4 (40.0%), followed by genotype 2 (5.6%). The main characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1.

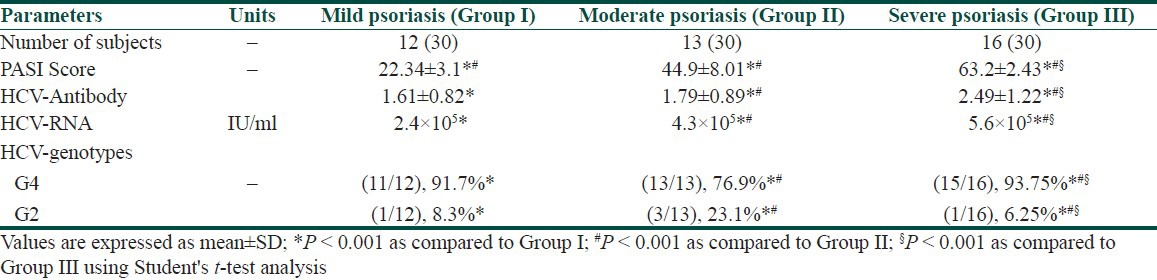

The patients with psoriasis were clinically classified according to PASI as mild, moderate and severe [Table 1]. Anti-HCV antibodies were detected in 40.0% (12/30), 43.3% (13/30), and 53.3% (16/30) of patients with mild, moderate, and severe psoriasis, respectively. In addition, patients with severe psoriasis showed significant higher (P < 0.001) HCV-RNA PCR values compared to (P < 0.001) mild, and moderate psoriatic patients. In the same manner, in severe psoriatic patients, the most prevalent HCV genotype was genotype 4 (15/16; 93.75%) as compared to (P < 0.001) mild and moderate patients. However, genotype 2 showed prevalence rate in moderate psoriatic patients (3/13; 23.1%) compared to (P < 0.001) mild and severe patients. There was a significant increase (P < 0.001) in PASI score values in positive anti-HCV patients with severe psoriasis as compared to patients with mild and moderate psoriasis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Correlation of severity of psoriasis (PASI) with HCV-biomarkers in psoriatic patients

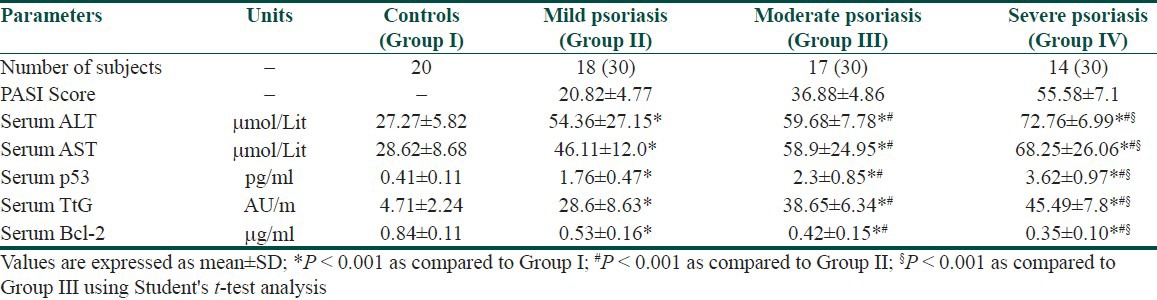

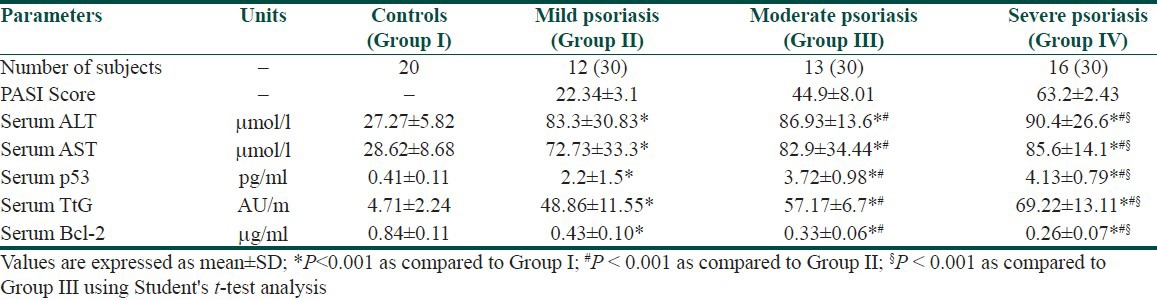

There was a significant increase (P < 0.001) in the level of ALT and AST in all patients with psoriasis compared to controls. Patients with psoriasis positive anti-HCV antibodies showed significant increase (P < 0.001) in the level of ALT and AST when compared to psoriatic patients lacking anti-HCV antibodies [Tables 3 and 4]. There was a significant increase in the expression of p53 and tTG associated with a significant decrease in bcl-2 protein expression in all patients with psoriasis compared to controls. Psoriatic patients with positive anti-HCV abs showed a significant (P < 0.001) higher expression of p53 and tTG associated with significant (P < 0.001) lower expression of bcl-2 compared to those with negative anti-HCV antibodies [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Apoptosis and severity of psoriasis (PASI) measured according to the values ALT, AST, p53, TtG, and Bcl-2 in controls and patients with psoriasis

Table 4.

Apoptosis and severity of psoriasis (PASI) measured according to the values ALT, AST, p53, TtG, and Bcl-2 in controls and patients with psoriasis HCV

Severe psoriatic patients with positive anti-HCV antibodies showed significantly (P < 0.001) higher serum levels of p53 and tTG associated with a significantly (P < 0.001) lower serum level of bcl-2 proteins as compared to moderate and mild psoriatic patients with positive anti-HCV antibodies [Tables 3 and 4]. There was a positively significant (P < 0.001) correlation reported between p53 and TtG and negative correlation (P < 0.001) with bcl-2 in psoriatic patients with or without anti-HCV antibodies. Also, in relation to the severity of psoriasis (PASI), positively significant (P < 0.001) correlation was reported towards p53 and tTG and negative correlation (P < 0.001) with bcl-2. Similarly, in psoriatic HCV patients, the values of HCV-RNA showed positively significant (P < 0.001) correlations with PASI score, p53 and tTG and negative correlation (P < 0.001) with bcl-2 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation analysis of different parameters among different psoriatic patients

Discussion

There are varied etiological factors in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Recently, it has been proposed that HCV viral antigens are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.[4,5,6] HCV antibodies are more frequently found in patients with psoriasis than in the normal population. It has been reported that 10.7% of patients were shown to be infected with HCV in the psoriasis group as compared to 2% in the control group.[6] The high anti-HCV prevalence in this study may be attributed to infection by inapparent routes, through minute psoriatic skin abrasions.

In this work, psoriatic patients with positive HCV antibodies showed significant increased values (P < 0.001) in PASI score as compared to negative patients suggesting that HCV infection may contribute to the severity of psoriasis. The results confirmed with higher significant values of HCV-mRNA, which showed significant association with the severity of psoriasis. Anti-HCV antibodies were found in 8 (79) patients with psoriasis by detection of HCV-mRNA in the tissues of the lesions of psoriasis patients.[8] It is suggested that active viral replication in the skin lesion might be one of the triggering factors of the severity of psoriasis. The data obtained from this study showed a statistically significant correlative relationship between the clinical severity of psoriasis and the presence of HCV antibodies. In addition, genotyping analysis showed a significant prevalent ratio of HCV-genotype 4 in severe psoriatic patients as compared to mild and moderate cases, that could explain the increased severity of psoriasis in HCV patients and that psoriatic lesions may be a suitable route of HCV distribution. These changes may be due to the metabolic and biochemical alterations present in such patients or to the direct effect of the virus, which promotes liver cell failure. This may be manifested in the skin disorders.[21]

On the other hand, psoriasis may affect the liver condition. In the present study, ALT and AST were estimated as biochemical liver markers in the patients and control groups. In patients with severe psoriasis, a significant increase (P < 0.001) in the level of ALT and AST was noticed as compared to mild and moderate groups. The increased levels of ALT and AST in patients with psoriasis indicate that psoriasis may promote liver disorder. The presence of varying degrees of liver cell damage with elevations in the liver function tests in patients with psoriasis was reported and psoriasis itself may cause damage to the liver, which is relatively less than the damage caused by HCV.[9] There is an association between higher titers of ALT and AST and the severity of psoriasis. The presence of abnormal biological liver parameters in 47% of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis, which is not attributed to methotrexate treatment indicates the effect of psoriasis on liver condition.[9] The prevalence of HCV infection in psoriasis patients may add to liver dysfunction.

Apoptosis is a physiological form of cell death that is responsible for the deletion of cells in order to keep and regulate the structural homeostasis of the skin. It has been reported that interferon affects the expression of apoptosis molecules.[10] In this study, none of the patients was treated with interferon. The expression of the pro-apoptotic protein p53 in the psoriatic skin was studied and the data obtained revealed overexpression in keratinocytes of the basal and supra basal layers of psoriatic epidermis.[12] The pivotal role of bcl-2 protein in cell homeostasis of psoriatic patients is negative regulation by the overexpression of p53 or tTG pro-apoptotic proteins.[13,14] All previous researchers who studied the apoptosis markers in psoriasis have localized those markers in patients’ skin.

In this study, we found severity wise increase of p53 and tTG and a decrease in bcl-2 expression in the serum of both anti-HCV-negative and positive patients with psoriasis. However, a significantly higher value of p53 and tTG and lower Bcl-2 values were reported in psoriatic patients with anti-HCV antibodies as compared to anti-HCV-negative patients. Especially when taking into consideration that apoptosis induction in patients with HBV or HCV is considered by some authors as a defense mechanism to limit viral replication and promote their elimination.[22] Serum Bcl-2 level was measured in patients with viral hepatitis; the data obtained showed a significantly elevated Bcl-2 level in the serum of liver cancer as compared to cirrhosis and chronic cases.[23] In addition, a recent study on psoriatic patients showed that there is no difference in the level of serum Bcl-2 before and after topical treatment and no significant difference between patients with mild and severe psoriasis was reported.[24] The exact source of these apoptosis-regulating proteins in the blood of the patients is not known. It may be from the psoriatic skin lesions as there was a significant increase of the serum levels of p53 and tTG and significant decrease of the serum levels of bcl-2 in the serum of the patients as compared to the controls. Previous studies showed a significant reduction in the amount of apoptosis-blocking gene Bcl-2 in basal layer of psoriatic epidermis and a presence of tissue transglutaminase (tTG) in it, specifically placed in cytoplasm of epidermal apoptotic cells. Thus, significantly high titers of antibodies against tTG in psoriatics are likely to result from the response to this protein expression in psoriatic lesions.[25,26,27,28] Moreover, the data matched with that of El-Domyati et al.[29] who reported that psoriatic plaques revealed p53 overexpression in keratinocytes Bcl-2 overexpression in lymphocytes, and absent apoptotic cells.

In psoriasis, many investigators reported over-expression of p53 in the keratinocytes of both psoriatic and non-lesional skin with higher expression of p53 in lesional than in non-lesional skin. This p53 overexpression was explained as a physiological reaction to hyperproliferation. Bcl-2 expression was found to be suppressed in the keratinocytes of psoriatic lesions. Thus, because of its limited expression, Bcl-2 is believed to be not directly associated with cell proliferation or apoptotic resistance in psoriasis;[30,31] this confirms our results that showed significant decrease of bcl-2 psoriatic patients with varying clinical severity. However, overexpression of p53 protein was the only common finding in HCV liver disease patients, which could be attributed to significant DNA damage during apoptosis.[32] Positive correlation between PASI, HCV-RNA, tTG, P53, and negative correlation with Bcl-2 in anti-HCV positive and anti-HCV negative psoriatic patients in our results can partially confirm this suggestion. These findings suggest that an alteration in the proliferation/apoptosis balance is present in the skin of such patients. It is still unclear whether skin diseases associated with HCV infection and characterized histopathologically by apoptosis or necrosis,[33,34] are due to an exaggerated response to such alteration. Also, the increase of apoptotic relating proteins may be related to the regulatory functions of HCV core protein which regulates the signaling pathways, cellular gene expression, and cell growth.[35,36] Liver abnormalities may be another possible source of the apoptosis regulating proteins in the serum of the patients. We found significant increase in the liver enzymes of mild, moderate and sever psoriasis patients. Damage of the liver cells may be caused by chronic inflammation, mediated by either pro-inflammatory skin-derived cytokines or adipokines which may contribute to fatty liver disease and may act on the skin to influence psoriasis disease severity.[37,38] Impaired liver function and liver cell death by apoptosis can either be caused or aggravated by psoriasis. This study showed that liver dysfunction is increased in anti-HCV positive psoriasis patients. The serum levels of liver enzymes are significantly higher in anti-HCV positive patients than negative patients. The liver insult in those patients may be caused of both HCV infection and psoriasis.

Conclusion

We have shown that abnormal expression of apoptosis-regulating proteins p53, tTG, and bcl-2 along with HCV infection are closely related to the clinical severity of psoriasis. These results suggest that the presence of HCV infection might be one of the triggering factors of psoriasis. Finally, determination of apoptosis-regulating proteins in the serum could be useful as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets of psoriatic disease.

What is new?

Abnormal expression of apoptosis-regulating proteins p53, tTG, and bcl-2 closely related to the clinical severity of psoriasis. Determination of apoptosis-regulating proteins in the serum could be useful as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets of psoriatic disease.

Significant correlative relationship between the clinical severity of psoriasis and the presence of HCV antibodies and HCV-mRNA was reported.

HCV genotyping analysis showed a significant correlation between HCV genotype 4 and clinical severity of psoriasis and HCV infection, which may be a route of distribution through psoriatic lesions.

Acknowledgement

Authors extend their appreciation to Rehabilitation Research Chair (RRC), King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Sabat R, Philipp S, Höflich C, Kreutzer S, Wallace E, Asadullah K, et al. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:779–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das RP, Jain AK, Ramesh V. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:7–12. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.48977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen AD, Weitzman D, Birkenfeld S, Dreiher J. Psoriasis associated with hepatitis C but not with hepatitis B. Dermatology. 2010;220:218–22. doi: 10.1159/000286131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doutre MS. Hepatitis C virus-related skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1401–3. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.11.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chouela E, Abeldaño A, Panetta J, Ducard M, Neglia V, Sookoian S, et al. Hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV): Prevalence in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:797–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb02977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson JM. Hepatitis C and the skin. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:449–58. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JW, Kim KJ, Lee CJ. A study of the relationship between psoriasis and viral hepatitis. Korean J Dermatol. 1997;36:266–74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto T, Katayama I, Nishioka K. Psoriasis and hepatitis C virus. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:482–3. doi: 10.2340/0001555575482483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borges-Costa J, Silva R, Goncalves L, Filipe P, Soares de Almeida L, Marques Gomes M, et al. Clinical and laboratory features in acute generalized pustular psoriasis: A retrospective study of 34 patients. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:271–6. doi: 10.2165/11586900-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens MJ. Interferons and apoptosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23:277–92. doi: 10.1089/107999003766628124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laporte M, Galand P, Fokan D, de Graef C, Heenen M, et al. Apoptosis in established and healing psoriasis. Dermatology. 2000;200:314–6. doi: 10.1159/000018394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baran W, Szepietowski JC, Szybejko-Machaj G. Expression of p53 protein in psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2005;14:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koçak M, Bozdogan O, Erkek E, Atasoy P, Birol A. Examination of Bcl-2, Bcl-X and bax protein expression in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:789–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucholski J, Johnson GV. Tissue transglutaminase differentially modulates apoptosis in a stimuli-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2002;81:780–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Domyati M, Abo-Elenin M, Hosam El-Din W, Abdel-Wahab H, Abdel-Raouf H, El-Amawy T, et al. Expression of apoptosis regulatory markers in the skin of advanced hepatitis-C virus liver patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:187–93. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.96189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senturk N, Yildiz L, Sullu Y, Kandemir B, Turanli AY. Expression of bcl-2 protein in active skin lesions of Behcet's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:747–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabr SA, Al-Ghadir AH. Role of cellular oxidative stress and cytochrome c in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:451–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louden BA, Pearce DJ, Lang W, Feldman SR. A simplified psoriasis area severity index (SPASI) for rating psoriasis severity in clinical patients. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boom R, Sol CJ, Salimans M, Jansen CL, Wertheim-van DPM, Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto H, Sugiyama Y, Okada S, Kurai K, Akahane Y, Sugia A, et al. Typing hepatitis C virus by PCR with type-specific primers. Application to clinical surveys and tracing infectious sources. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:673–9. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-3-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenk KS, Arrington KC, Ehrlich A. Psoriasis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:383–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman RW, Collier JD, Hayes PC. Liver and biliary tract disease. In: Nicholas A, Nicki R, Brian R, editors. Davidsons's Principles and Practice of Medicine. 20th ed. USA: Elsevier Science; 2006. pp. 935–98. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osman HG, Gabr OM, Lotfy S, Gabr S. Serum levels of bcl-2 and cellular oxidative stress in patients with viral hepatitis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:323–9. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mysliwiec H, Flisiak I, Baran A, Górska M, Chodynicka B. Evaluation of CD40, its ligand CD40L and Bcl-2 in psoriatic patients. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2012;50:75–9. doi: 10.2478/18699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel T. Apoptosis in hepatic pathophysiology. Clin Liver Dis. 2000;4:295–317. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creamer D, Allen MH, Sousa A, Poston R, Barker JN. Localisation of endothelial proliferation and microvascular expansion in active plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:859–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fesus L, Davies PJA, Piacentini M. Apoptosis: Molecular mechanisms in programmed cell death. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991;56:170–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bianchi L, Farrace MG, Nini G, Piacentini M. Abnormal Bcl-2 and ‘tissue’ transglutaminase expression in psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:829–33. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12413590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Domyati M, Mana1 Barakat Ma, Abdel-Razek R. Expression of apoptosis regulating proteins, P53 and Bcl-2 in psoriasis. J Egypt wom Dermatol Soc. 2006;3:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tadini G, Cerri A, Crosti L, Cattoretti G, Berli E. P53 and oncogenes expression in psoriasis. Acra Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1989;146:33–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannuksela-Svahn A, Paakko P, Autio P, Reunala T, Karvonen J, Vahakangas K. Expression of p53 protein before and after PUVA treatment in psoriasis. Acra Derm Venereol. 1999;79:195–9. doi: 10.1080/000155599750010959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi H, Manabe A, Ishida-Yamamato A, Hashimoto Y, Lizuka H. Aberrant expression of apoptosis-related molecules in psoriatic epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;28:187–97. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(01)00162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wrone-Smith T, Mitra RS, Thompson CB, Jasty R, Castle VP, Nickoloff BJ. Keratinocytes derived from psoriatic plaques are resistant to apoptosis compared with normal skin. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1321–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Domyati M, Ahmad HM, Nagy I, Zahran A. Expression of apoptosis regulatory proteins p53 and Bcl-2 in skin of patients with chronic renal failure on maintenance haemodialysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi J, Lu W, Ou J-h. Structure and functions of hepatitis C virus core protein. Recent Res Devl Virol. 2001;3:105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu W, Strohecker A, Ou Jh JH. Post-translational modification of the hepatitis C virus core protein by tissue transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47993–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creamer D, Allen MH, Sousa A, Poston R, Barker JN. Localisation of endothelial proliferation and microvascular expansion in active plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:859–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alkhouri N, Carter-Kent C, Feldstein AE. Apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:201–2. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]