Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous melanoma (CM) has a high propensity for regional and systemic spread. This is one of the largest series of CM reported from India.

Aims:

To predict factors for loco regional recurrence (LRR) and distant metastasis in patients with CM primarily treated with surgery.

Study Design:

Retrospective analysis of patient database at a tertiary care cancer center with evaluation of factors for LRR and distant metastasis for CM.

Materials and Methods:

Data from 68 patients treated for CM between January 2006 and December 2010 were reviewed. Data recorded included age, sex, symptoms, investigations, treatment given, histopathology, recurrence and follow-up. Patient factors, tumor factors, pathologic variables, and adjuvant treatment were investigated as predictors’ of LRR and distant metastasis.

Results:

Mean age of patients was 54 years. Melanoma was more common in males (44). Tumor thickness > 4 mm was found in 43 patients. Lymph node involvement was found in 43 patients. Adjuvant radiotherapy was given in seven patients. At mean follow-up of 16.5 months, LRR was seen in 34 patients and distant metastasis in 28 patients. LRR and distant metastasis were more commonly found in females, age > 40 years, Clark's level IV and V, Breslow's depth > 4 mm, patients with lymph node involvement and extra-capsular spread.

Conclusion:

The age, sex, site, thickness of lesion, involvement of lymph node, and extra-capsular spread were important factors in predicting LRR and distant metastasis. Distant metastasis was also more commonly found in patients with LRR.

Keywords: Cutaneous melanoma, distant metastasis, locoregional recurrence, predictive factors for recurrence, prognostic factors

Introduction

What was known?

Melanoma is one of the most lethal malignancies with a high propensity for regional and systemic spread.

Melanoma is a neoplastic disorder produced by malignant transformation of the normal melanocyte. Cutaneous melanoma (CM) accounts for only 4-5% of skin cancers but causes majority of deaths from skin cancers.[1] Majority arise de novo and only 23% arise from pre-existing nevi.[2] CM disproportionately affects whites over blacks.[3] These statistics are based on incidence rates in the Western world where CM is common. Although, the incidence of skin cancers in India is lower as compared to the Western world, because of a large population, absolute number of cases is estimated to be significant.[4]

Diagnosing CM at an early stage is the key to improved prognosis. In most Western countries, this knowledge has encouraged prevention and early detection.[5] The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recently established a new staging system based on a large study that included 30,946 CM patients.[6] Recent data suggest that depth of invasion, ulceration, age, sex and anatomical location are the adverse predictors of survival in CM.[7] Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment. Adjuvant radiotherapy has a role in decreasing loco regional recurrence (LRR).[8] No current systemic treatment regimen has shown conclusive benefit.[9]

In spite of being a surface malignancy and more amenable not only to early detection, but also to a potential cure, CM has a lower overall survival rate compared to other skin cancers due a high propensity for regional and systemic spread.[4] A better understanding of prognostic factors in CM has evolved over the last decade. These prognostic factors can, therefore, identify distinct subgroups of melanoma patients with respect to recurrence and metastatic risk which affects the survival rates. Treatment outcome and follow-up data about survival is scarce from the Indian population. Hence, this study was undertaken to know the treatment outcome and to evaluate patient factors, tumor factors, pathologic variables and adjuvant treatment as predictors of LRR and distant metastasis of patients treated at a tertiary care regional cancer center.

Materials and Methods

Patient records of 68 patients with CM treated at surgical oncology department at a regional cancer center between January 2006 to December 2010 were reviewed retrospectively and analyzed.

Patients were first evaluated in the outpatient clinic by a team of surgical oncologists and they underwent treatment according to the protocol decided by the same team. Apart from history and detailed clinical assessment, diagnosis was done with biopsy and the pretreatment work up included routine blood examination, chest X-ray and ultrasound abdomen. Imaging studies (Contrast enhanced computer tomography/Magnetic resonance imaging) were used only in locally advanced lesions to assess the extent of local infiltration and metastasis. Ultrasound of the abdomen was used to evaluate any visceral or lymph nodal metastases. In patients with enlarged regional lymph nodes, fine needle aspiration cytology was carried out to look for regional spread.

Operative procedures varied according to the site and local extent of the disease. Width of surgical margins varied between 1-2 cm according to the depth of the lesion. For patients with CM of the extremities, where the disease had completely encased the neurovascular bundle or infiltrated bones, amputations were performed. In patients with positive margin, re-excision of the scar tissue and tumor bed was carried out. For large surgical defects not suitable for primary closure, reconstruction using split thickness skin grafts were performed. In primary setting, comprehensive regional lymph node dissection was performed if there was clinical evidence of nodal involvement, and was done prophylactically in patients with tumor depth > 4mm. In secondary setting regional lymph nodal dissection was done on regional nodal recurrence.

Adjuvant radiotherapy (50Gy/25# over 5 weeks) was given in cases with positive tumor margins, with locally advanced growths and in patients with positive nodal disease. Adjuvant systemic therapy was given in patients with nodal involvement. After completion of treatment, all the patients were followed up at three monthly intervals to look for relapse of disease. Chest X-ray and ultrasound abdomen was done every 6 months.

Patient factors, tumor factors, pathologic variables and adjuvant treatment were investigated as predictors of LRR and distant metastasis and results were analyzed.

Results

Skin cancers constituted 1.13% of all cancers (475/42180) treated in the surgical oncology department at our institute between January 2006 and December 2010. Among skin cancers malignant melanoma accounted for 21% (100/475) of cases. Out of 100 CM patients, 68 patients were treated surgically and remaining 32 patients with palliative care as they presented with advanced stage. Only these 68 patients who were surgically treated were analyzed for predictors of LRR and distant metastasis.

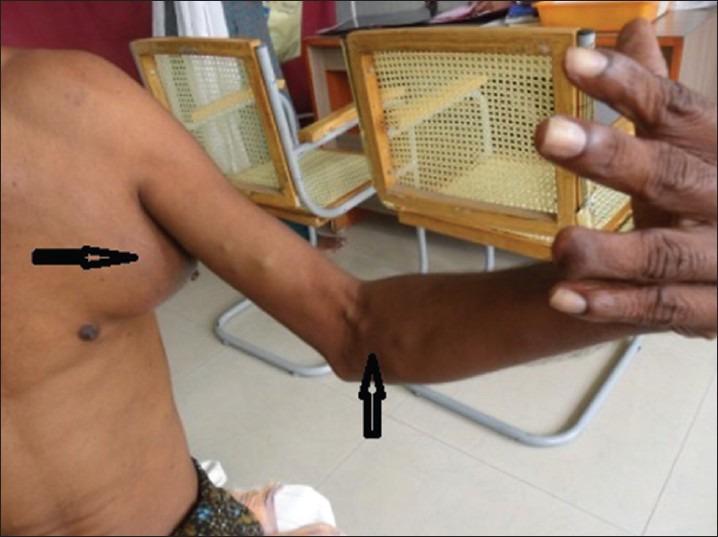

Mean age of patients was 51.8 years (range 19-81 years).44 were men and 24 were women (M:F; 1.8:1). Most patients presented with swelling (44) and/or ulcer (30) or blackish pigmented lesion (14). Nineteen patients had undergone some form of intervention outside before being referred, with wide local excision being the most common. Six patients had preexisting nevi, two patients had Xeroderma Pigmentosa [Figure 1] and one patient had albinism.

Figure 1.

A case of Xeroderma Pigmentosa who developed multiple cutaneous melanoma over head and neck region

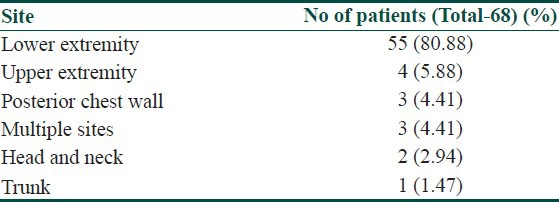

Most common site of involvement was local extremity (55). Distribution of primary sites is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of primary sites

Sixteen patients (23.5%) had regional lymph nodal involvement clinically.

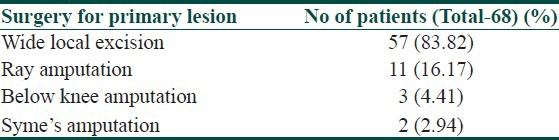

Most of the patients underwent wide local excision (57 patients). Eleven patients underwent amputation (ray amputation in six patients, below knee amputation in three patients and Syme's amputation in two patients). Management of primary lesion is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Management of primary lesion

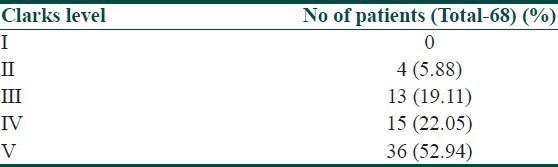

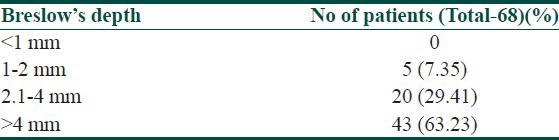

Immunohistochemistry was positive for HMB-45 (Human Melanoma Black) and S-100 in all patients. Three patients had margin positivity. Most of the patients had tumor thickness of Clark's level V and Breslow's depth > 4 mm. Clark's levels and Breslow's depth is summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Clark's level distribution

Table 4.

Breslow's depth distribution

Forty nine patients underwent lymph node dissection either in primary setting (29 patients) or secondary setting (20 patients). Forty three patients had involvement of nodes. Thirty patients had extracapsular spread. Twelve patients received radiotherapy. Out of which five patients received palliative radiotherapy to brain, four patients received adjuvant radiotherapy to primary site and three patients received adjuvant radiotherapy to nodal site. Thirteen patients received one of the following regimens (cisplatin + dacarbazine, dacarbazine + interferon, cisplatin + vinblastine + dacarbazine, interferon, Immuvac or Tamoxifen) as systemic therapy.

Median follow-up of 16.5 months (1-68 months). Thirty four patients (50%) had LRR and 28 patients (41%) had distant metastasis. Mean duration for LRR was 9.1 months. Most common site for LRR was regional nodes (22 patients) [Figure 2], followed by skip lesions (in transit metastasis) in nine patients [Figure 3]. Different sites of LRR are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 2.

A post-operative case of cutaneous melanoma of left ring finger who developed loco regional recurrence (skip lesions and regional nodes)

Figure 3.

A case of cutaneous melanoma of lower extremity who developed skip metastasis

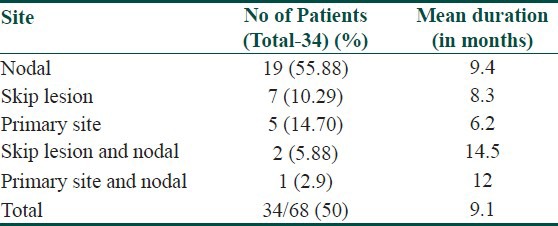

Table 5.

Different sites of LRR

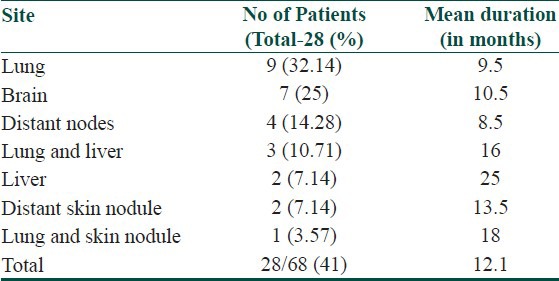

Mean duration for distant metastasis was 12.1 months. Most common site for distant metastasis was lung (13 patients), followed by brain (seven patients). Occurrence of distant metastasis is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Different sites of distant metastasis

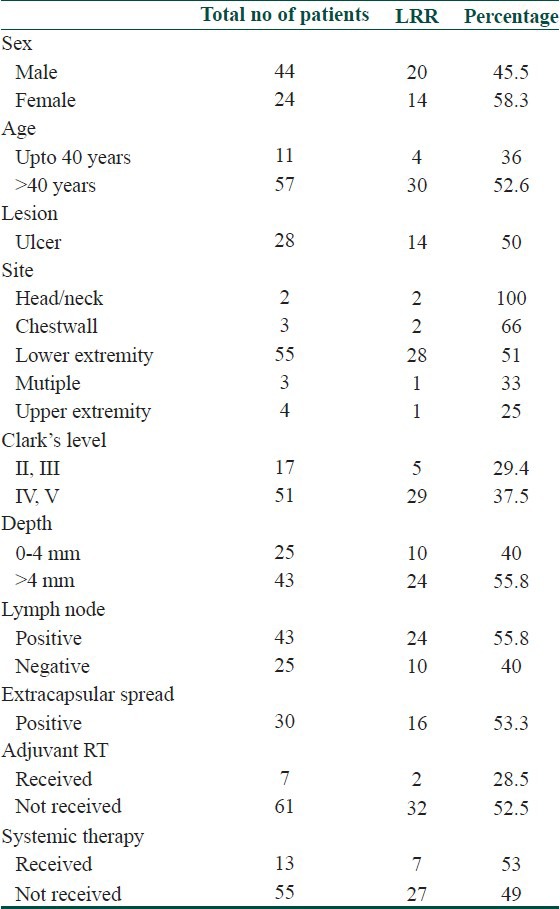

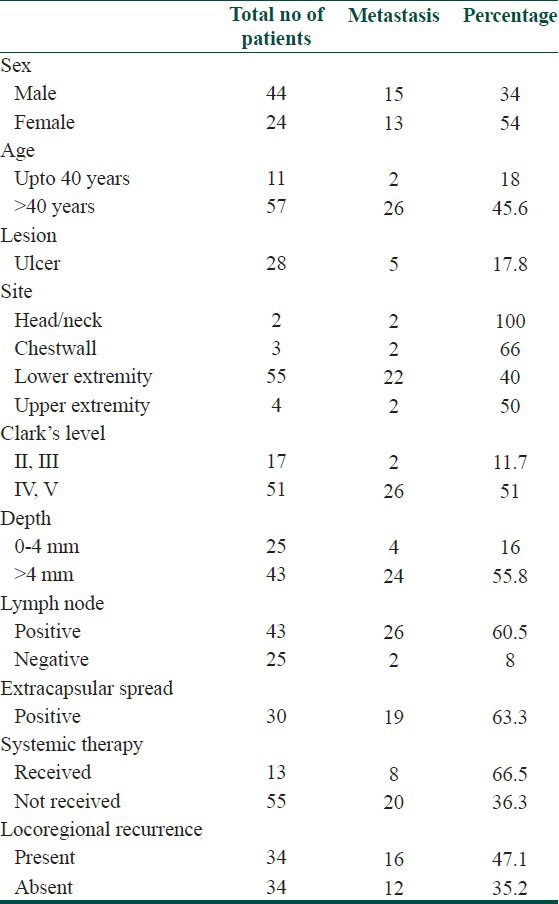

Patient factors, tumor factors, pathologic variables and adjuvant treatment were investigated as predictors of LRR and distant metastasis. Both LRR and distant metastasis was seen more in female patients, age > 40 years, head and neck and chest wall site, Clark's level IV and V, Breslow's depth > 4 mm, involvement of lymph node and presence of extracapsular spread. Distant metastasis was also seen more in patients with LRR than who did not. Presence of ulceration did not increase the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis in our study. Adjuvant radiotherapy decreased the incidence of LRR. Systemic therapy did not affect the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis. Predictive factors for LRR and distant metastasis are summarized in Tables 7 and 8 respectively.

Table 7.

Predictive factors for LRR

Table 8.

Predictive factors for distant metastasis

Discussion

At our regional cancer institute skin cancer comprised 1.13% of all cancers (475/42180) in our study period. Among skin cancer, malignant melanoma accounted for 21% of cases. Although there has been no significant increasing trend in the age-adjusted incidence of skin cancers in Indian patients, but in the Western countries, the incidence of skin cancers, especially of malignant melanoma has been rising for the past 40 years.[10,11]

Various studies have evaluated predictive factors for LRR and distant metastasis like age, sex, site, presence of ulcer, tumor thickness and lymph node involvement.[12,13] However, tumor thickness and anatomic location has been the subject of extensive debate concerning their significance and stratifications. In the present study, evaluation revealed tumor thickness, lymph node involvement, extra-capsular spread, body site, sex, and age as significant prognostic factors, whereas ulceration and adjuvant systemic therapy did not seem to have an independent significant effect on the prognosis of CM.

Older patients present more frequently with thicker and ulcerated melanomas and many studies have reported age to be an independent prognostic factor.[13,14] Similarly in our study patients with age > 40 years had higher LRR (52.6%) and distant metastasis (45.6%).

Previous studies have shown that women have a better prognosis compared to men.[15,16] In Studies by Balch et al. and McKinnon et al., in addition to the patient's age, sex (males with poorer prognosis than females) and anatomic site (trunk and head and neck sites with poorer prognosis than extremities) correlated significantly with survival, although their χ2 values were much lower compared with those for melanoma thickness and ulceration.[17,18] Our study showed that LRR and distant metastasis was more common in women.

In a series of 5,093 patients by Garbe et al. with invasive primary CM, locations that were associated with a significantly higher risk of death included the back, thorax, upper arm, neck, and scalp.[19] Similarly, in our study, patients with head and neck and chest wall location had higher LRR (80%) and distant metastasis (80%).

The general management of primary melanoma lesions is surgical resection. However, there is a role for definitive or adjuvant radiation therapy in certain histologic variants including, lentigo maligna, desmoplastic melanoma, or neurotropic melanoma and for palliation of unresectable primary disease.[8] Post-operative adjuvant radiation may be delivered with 2-3 cm margins around the resected lesion if margins are inadequate, or following resection of a locally recurrent lesion, as this can substantially reduce subsequent local recurrences.[8] Our study also showed that adjuvant radiotherapy decreased the incidence of LRR (28.5%) compared to patients who did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy (52.5%).

No current systemic treatment regimen has shown conclusive benefit. Clinical trials combining chemotherapy have produced promising response rates in single arm, single-institution studies, but have never demonstrated an improvement in overall survival compared with single agent chemotherapy in multicenter randomized trials. Given the increased toxicity associated with such regimens, the modest improvements in progression free survival and absence of a survival advantage limit their consideration as standard therapies. Similarly in our study systemic therapy did not affect the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis.

In the 2009 AJCC analysis, 5 year survival within sub-stages of stage III were 78%, 59% and 40% for patients with stage IIIA, IIIB and IIIC melanoma, respectively.[6] Pathologically documented nodal metastases (by either sentinel or elective node dissection) are defined as microscopic, and clinically or radiologically documented nodal metastases are defined as macroscopic. Survival rates for these two patient groups are significantly different.[13] Studies of the detection of submicroscopic levels of disease in lymph nodes are currently underway.[20,21] Similarly, in our study, patients with lymph node involvement had higher LRR (55.8%) and distant metastasis (60.5%).

Tumor thickness and ulceration have been considered as the most powerful independent prognostic factors in localized CM.[6,7,22,23] Tumor depth is measured in millimeters from the granular layer of the epidermis to the deepest tumor cell. Increased tumor thickness is associated with poor survival. In the 1997 version of the melanoma staging system, the cut-off point between a T1 and T2 melanoma was defined as 0.75 mm.[24] In the 2002 AJCC system and 2010 AJCC system, melanoma thickness is stratified into four categories: ≤1.0 mm, 1.01-2.0 mm, 2.01-4.0 mm and > 4.0 mm. In our study patients with depth > 4 mm had higher LRR (55.8%) and distant metastasis (55.8%).

The Clark's level has been used to describe the anatomic involvement of the tumor within the cutaneous and subcutaneous structures. Level I is intra-epidermal growth with intact basement membrane, level II is invasion of the papillary dermis, level III is tumor involvement filling the papillary dermis and involvement of the junction between the papillary and reticular dermis, level IV is invasion of tumor into the reticular dermis, and level V is invasion of tumor cells into the subcutaneous fat.[25] The 5 year survival rate is 95% for Clark's level II melanomas, between 80% and 85% for Clark's level III and IV melanomas and 55% for Clark's level V melanomas.[23] In our study, patients with Clark's level IV and V had higher LRR (37.5%) and distant metastasis (51%). However, other studies have shown that Clark's level is not an independent predictor of outcome, even in thin melanomas.[26] For tumors thicker than 1 mm, Clark's level is less predictive than ulceration, patient age, or anatomic location and also has limited utility.

Ulceration is defined histologically as the absence of an intact epidermis overlying a significant portion of the primary tumor.[27] As noted above, the two most powerful independent characteristics of the primary melanoma are ulceration (which was not included in the older staging system) and tumor thickness. These factors are highly correlated with each other in previous studies which have shown that the incidence of melanoma ulceration rose with increasing tumor thickness, ranging from 6% to 12.5% for thin melanomas to 63-72.5% for thick (>4.0 mm) lesions.[6,27] The presence of ulceration decreases survival in all tumor thickness categories. This observation led to the inclusion of ulceration as the second determinant for the T-classification in the new staging system and the only primary tumor factor to modify the prognosis of node positive disease.[24] However, in our study presence of ulceration did not increase the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis.

Newer factors, such as vascular invasion may continue to refine the prognostic information gained by knowledge of the tumor thickness alone. Finally, genetic (such as BRAF [v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1] mutation status) and molecular prognostic factors (such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) await further validation before they enter routine clinical use.

Conclusion

CM is a rare disease at our center. Late presentation with advanced disease is a common feature in our environment. A better understanding of prognostic factors in CM has evolved over the last decade. Many of the prognostic factors are interrelated. The sex, age, site, thickness of lesion, involvement of lymph node and extra-capsular spread were important factors in predicting LRR and distant metastasis. The importance of ulceration as a prognostic factor has emerged in recent studies. However, in our study, presence of ulceration did not increase the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis. Our study also showed that adjuvant radiotherapy decreased the incidence of LRR, while systemic therapy did not affect the incidence of LRR or distant metastasis. In the near future, it is expected that several molecular genetic factors will become important as prognostic factors in melanoma. These prognostic factors can, therefore, identify distinct subgroups of melanoma patients with respect to recurrence and metastatic risk which affects the survival rates. Though the rarity of the disease limits the feasibility of clinical trials, a comprehensive, multi-institutional, prospective data collection would augment our understanding of risk-factors and prognostic factors as well as improve management of CM in Indian subset of patients.

What is new?

This paper addresses the lack of data in the Indian population on predictive factors for LRR and distant metastasis in CM.

Acknowledgment

Department of Surgical oncology, Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, Bangalore

Department of Head and Neck oncology, Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, Bangalore

Department of Pathology, Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, Bangalore

Department of Anaesthesia, Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, Bangalore.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harley S, Walsh N. A new look at nevus-associated melanomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:137–41. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: A summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1998;83:1664–78. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1664::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair MK, Varghese C, Mahadevan S, Cherian T, Joseph F. Cutaneous malignant melanoma – Clinical epidemiology and survival. J Indian Med Assoc. 1998;96:19–20. 28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh HK, Geller AC, Miller DR, Grossbart TA, Lew RA. Prevention and early detection strategies for melanoma and skin cancer. Current status. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mervic L. Prognostic factors in patients with localized primary cutaneous melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2012;21:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vongtama R, Safa A, Gallardo D, Calcaterra T, Juillard G. Efficacy of radiation therapy in the local control of desmoplastic malignant melanoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:423–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veronesi U, Adamus J, Aubert C, Bajetta E, Beretta G, Bonadonna G, et al. A randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy in cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:913–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210073071503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnamurthy S, Yeole B, Joshi S, Gujarathi M, Jussawalla DJ. The descriptive epidemiology and trends in incidence of nonocular malignant melanoma in Bombay and India. Indian J Cancer. 1994;31:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doll R. Are we winning the fight against cancer? An epidemiological assessment. EACR–Mühlbock memorial lecture. Eur J Cancer. 1990;26:500–8. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90025-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soong SJ, Harrison RA, McCarthy WH, Urist MM, Balch CM. Factors affecting survival following local, regional, or distant recurrence from localized melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:228–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199804)67:4<228::aid-jso4>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI, Urist MM, Karakousis CP, Temple WJ, et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0 to 4.0 mm) Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang CK, Jacobs IA, Vizgirda VM, Salti GI. Melanoma in the elderly patient. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1135–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.10.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Måsbäck A, Olsson H, Westerdahl J, Ingvar C, Jonsson N. Prognostic factors in invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma: A population-based study and review. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:435–45. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vossaert KA, Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Bart RS, Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, et al. Influence of gender on survival in patients with stage I malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:429–40. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70068-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3622–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinnon JG, Yu XQ, McCarthy WH, Thompson JF. Prognosis for patients with thin cutaneous melanoma: Long-term survival data from New South Wales Central Cancer Registry and the Sydney Melanoma Unit. Cancer. 2003;98:1223–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garbe C, Büttner P, Bertz J, Burg G, d’Hoedt B, Drepper H, et al. Primary cutaneous melanoma. Identification of prognostic groups and estimation of individual prognosis for 5093 patients. Cancer. 1995;75:2484–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2484::aid-cncr2820751014>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shivers SC, Wang X, Li W, Joseph E, Messina J, Glass LF, et al. Molecular staging of malignant melanoma: Correlation with clinical outcome. JAMA. 1998;280:1410–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.16.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sung J, Li W, Shivers S, Reintgen D. Molecular analysis in evaluating the sentinel node in malignant melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:29S–30S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchter L, Schultz DJ, Synnestvedt M, Trock BJ, Guerry D, Elder DE, et al. A prognostic model for predicting 10-year survival in patients with primary melanoma. The Pigmented Lesion Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:369–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soong SJ, Shaw HM, Balch CM, McCarthy WH, Urist MM, Lee JY. Predicting survival and recurrence in localized melanoma: A multivariate approach. World J Surg. 1992;16:191–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02071520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Atkins MB, Cascinelli N, Coit DG, Fleming ID, et al. A new American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1484–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000315)88:6<1484::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcoval J, Moreno A, Graells J, Vidal A, Escribà JM, Garcia-Ramírez M, et al. Angiogenesis and malignant melanoma. Angiogenesis is related to the development of vertical (tumorigenic) growth phase. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:212–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimotty PA, Guerry D, Ming ME, Elenitsas R, Xu X, Czerniecki B, et al. Thin primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: A prognostic tree for 10-year metastasis is more accurate than American Joint Committee on Cancer staging. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3668–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balch CM, Wilkerson JA, Murad TM, Soong SJ, Ingalls AL, Maddox WA. The prognostic significance of ulceration of cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1980;45:3012–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800615)45:12<3012::aid-cncr2820451223>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]