Abstract

Background:

Direct immunofluorescence examination is an important technique in the diagnosis of cutaneous inflammatory disorders including lichen planus, especially in clinically and histopathological doubtful cases.

Objective:

To study the diagnostic utility of intensity, number, and subtypes of positive immuno-reactants found in lichen planus.

Materials and Methods:

A detailed analysis of clinical as well as immuno-histological features of lichen planus cases was carried out.

Results:

The male to female ratio was 1:1.1. The largest number of patients was in 31-50 year age group. Itching was the most common presenting symptom. Papular lesions were seen in 53% cases. Remaining had hypertrophic (6), follicular (3) and mucosal (9) variants. Clinico-pathological discrepancies were observed in 3 patients. The characteristic histopathological changes including basal cell vacuolization, band-like lymphocytic infiltrate at dermo-epidermal junction were seen in all the biopsies while Civatte bodies were detected in 29% cases. The overall positive yield of direct immunofluorescence microscopy was 55%. Immune deposits at Civatte bodies and dermo-epidermal junction were detected in 47% and 8% of cases, respectively. Immunoglobulin M was the most common immunoreactant followed by immunoglobulin G.

Conclusions:

There was no correlation found between the number and intensity of Civatte bodies with clinical variants of disease and also between the number of positive immunoreactants and clinical severity of the disease. The frequency, number, and arrangement of Civatte bodies in clusters in the papillary dermis as well as multiple immunoglobulins deposition at the Civatte bodies on direct immunofluorescence of skin biopsies are important features distinguishing lichen planus from other interface dermatitis.

Keywords: Direct immunofluorescence, interface dermatitis, skin biopsy

Introduction

What was known?

Shaggy fibrinogen deposition, whether alone or combined with other immuno-reactants at dermo-epidermal junction plus any immunoreactant deposit at civatte bodies are the most important findings on direct immunofluorescence favoring the diagnosis of lichen planus.

The frequency, number and arrangement of civatte bodies in clusters in the papillary dermis as well as multiple immunoglobulins deposition at the civatte bodies on direct immunofluorescence of skin biopsies are important features distinguishing lichen planus from other interface dermatitis.

Lichen planus (LP) is a common dermatosis that affects the skin, mucosae, and nails. The typical rash of LP is well-described by the “5 Ps”: Well-defined pruritic, planar, purple, polygonal papules.[1] The microscopic appearance of LP is pathognomic and shows hyperparakeratosis with thickening of the granular cell layer, degeneration of the basal cell layer, and band-like lymphocytic inflammation in the sub-epidermal layer with Civatte body (CBs) formation.[2] The clinical diagnosis of LP can be confirmed by classical histopathological findings. However, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies may be helpful in patients with no specific clinical or histologic features, or with overlapping features of other diseases, e.g., discoid lupus erythematous (DLE).[3] We analyzed 38 cases of LP with detailed clinical, histological, and immunopathological features to emphasize the diagnostic utility of subtypes, intensity, and number of positive immunoreactants found in LP. An attempt was also made to study the correlation between the number of positive immunoreactants and clinical severity of the disease.

Subjects and Methods

All those cases of LP that attended the outpatient department of dermatology from 1998-2007 and where a complete clinical history, histopathological reports with slides, and DIF findings of the biopsied lesion were available, comprised the study material. These biopsies were taken in patients to confirm the diagnosis where clinical presentation was not characteristic of LP. The clinical data were collected from the files of the department of dermatology. The biopsies for histological examination were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and routinely processed for hematoxylin and eosin stain (H and E). The slides were independently reviewed to analyze the pathological features in detail by two observers. DIF was done on frozen sections. For DIF study, all the biopsies were obtained in holding fluid (Michel's medium) containing a saturated solution of ammonium sulfate in buffer at room temperature and stored at 4°C until cut. For the frozen section, the tissue was embedded in OCT (optimal cutting temperature) medium, and 4-5 micron sections were cut (minimum 10 sections). Two sections were layered on each slide, and the slides were stored at −20°C until they were stained. Optimally diluted fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled monospecific immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM, C3) were layered onto the sections and incubated at 37°C for 45 min – 1 h. The sections were washed in PBS (pH 7.2, 0.1 M) thrice and mounted in buffered glycerin and finally viewed under a Nikon OPTOHOT-2, UV microscope. DIF patterns were interpreted according to standard guidelines. The intensity and location of the positive immunoreactants were recorded along with other microscopic findings and then compared with the diagnoses, both clinical and histopathological. The intensity was graded in three levels (+, ++, and +++). We also recorded which among the 4 immunoreactants were present in each specimen.

Results

Clinical details of patients

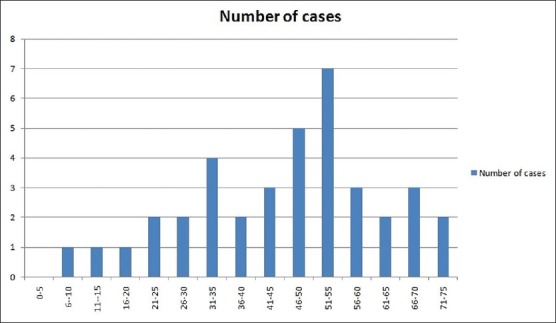

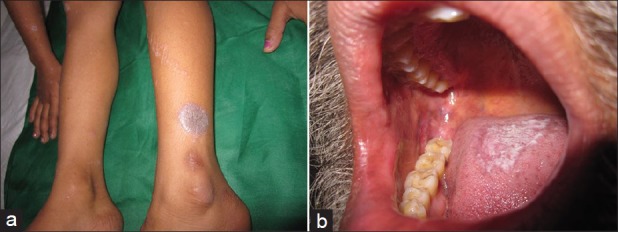

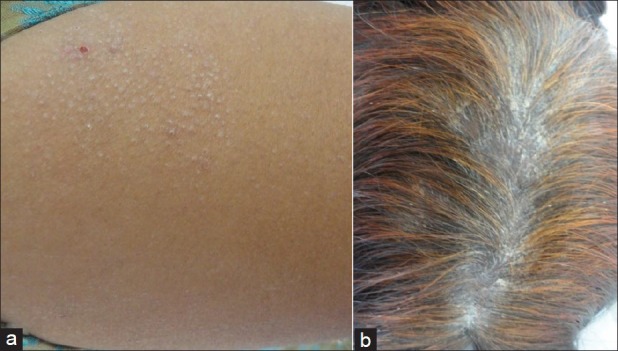

A total of 38 patients (18 males and 20 females) constituted the study cohort. Their age [Figure 1] ranged from 9-75 years (mean, 46.6 ± 16.5 years). A clinical diagnosis of LP was made in all the cases, except for 3 where a clinical possibility of dermatomyositis, bullous pemphigoid, and pyostomatitis vegetans was suggested, respectively. Duration of lesions ranged from 20 days to 34 months (mean 6.4 months). The site of biopsy was trunk in 15 patients followed by buccal mucosa (9 cases), legs (8 cases), arms (5 cases), and scalp (1 case). Majority of patients (20) had papular lesions in the form of violaceous polygonal papules with minimal scaling. Remaining had hypertrophic (6), follicular (3), and mucosal (9) variants of LP [Figures 2 and 3]. Common differential diagnoses considered in these patients were psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, and drug rash. Drugs (beta-blocker, anti-epileptics, and indigenous medications) as predisposing factor were suspected in 10 cases. Body surface area involvement due to LP varied from 2-5%. Itching was the commonest presenting symptom. Scalp and nails were involved in one case each. There was no family history of LP in any of the patient. Most of the patients had received topical corticosteroids and anti-histamines with partial relief in past. All hematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits.

Figure 1.

Age distribution in patients with lichen planus

Figure 2.

Clinical photographs showing (a) Violaceous flat-topped papules and plaques of classical lichen planus (b) Reticular plaque-type mucosal lichen planus involving tongue and cheek mucosa

Figure 3.

Clinical photographs showing (a) Peri-follicular lichenoid papules of follicular lichen planus with loss of hair at places (b) Lichen planus involving scalp with scarring alopecia and lichenoid infiltrated plaques

Histopathological analysis of biopsies

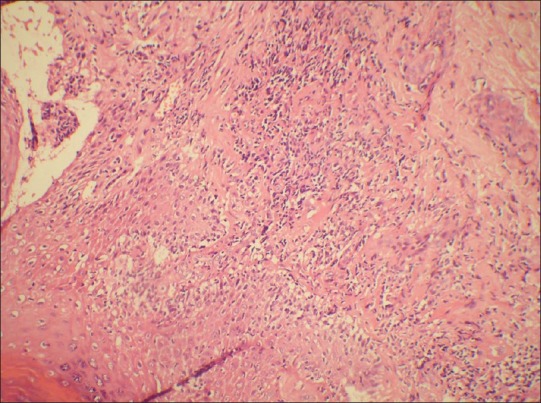

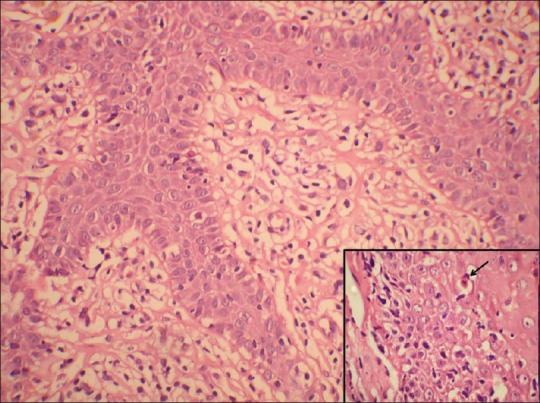

Out of 38 cases, 34 [including 3 cases, where a possibility other than LP was suspected clinically and 5 cases who were diagnosed clinically as hypertrophic (2 cases) and follicular (3 cases) lichen planus] showed histopathological features typical of classical LP [Figures 4 and 5]. Epidermal changes included hypergranulosis (82%), hyperkeratosis (92%), and basal cell vacuolization (100%). The dermis showed band-like lymphocytic inflammatory cell infiltrate, predominantly peri-vascular in location, in all cases. The infiltrate was mild in 45% (17/38), moderate in 37% (14/38), and severe in 13% (5/38) cases. In addition, 4 cases (clinically diagnosed as lichen planus hypertrophicus) showed marked irregular acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and compact orthokeratosis suggesting hypertrophic lichen planus. CBs were seen as round, eosinophilic bodies in the lower epidermis and papillary dermis in 11 cases (29%) with more numerous numbers in 4 cases (11%). Other features included pigment incontinence in 14, sub-epidermal bulla in 6, and keratotic plugging in 2 cases. No signs of epidermal dysplasia were observed in any of the samples.

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph showing basal cell vacuolization and lymphocytic infiltrate at dermo-epidermal junction. (H and E, ×100)

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph showing basal cell vacuolization and lymphocytic infiltrate at dermo-epidermal junction. (H and E, ×400). Inset showing civatte body

DIF results of biopsies

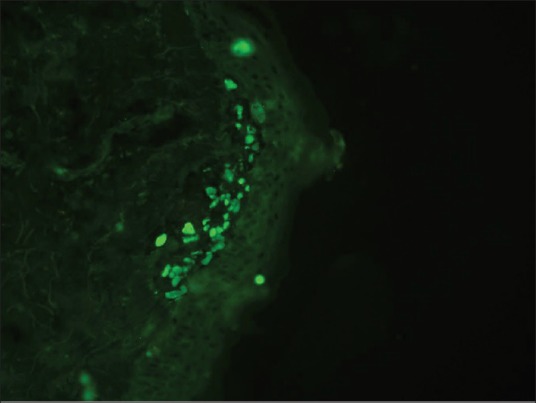

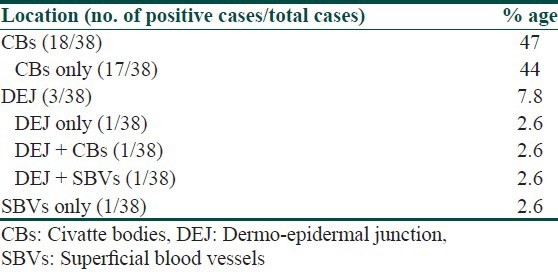

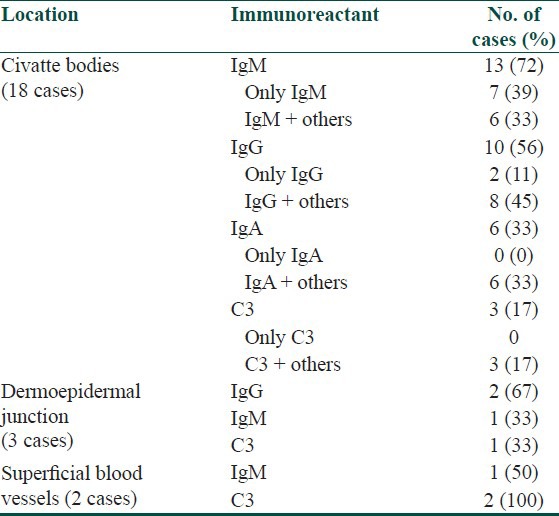

Of 38 cases, DIF study results showed positive findings in 21 (55%) skin biopsies. Immunofluorescence positivity at CBs was detected in 47% (18/38) cases [Figure 6] including 11 cases that showed CBs on HPE. The granular deposits of immunoreactants at dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) and superficial blood vessels were noted in 3 cases and 2 cases, respectively [Table 1]. Epidermal nuclear staining was not observed in any case. In all 18 cases, CBs were found to be deposited at DEJ and in the papillary dermis. None of the biopsies showed follicular or peri-follicular deposits of CBs. A brighter intensity (++ to +++) as well as more numerous number of CBs with clustering were observed in all CB positive cases. The most common immunoreactant at CBs was IgM, seen in 72% cases followed by IgG (56%), IgA (33%), and C3 (17%) [Table 2]. Brightest intensity (+++) was noted for immunoreactant IgM (56% cases). Combinations of various types of immunoreactants at CBs were seen in 50% cases. CBs involving more than 3 immunoreactants were noted in 22% cases. No correlation was found between the number of positive immunoreactants and clinical severity of the disease. We also did not observe any correlation between the number and intensity of CBs and clinical variants (classical, hypertrophic, mucosal, and follicular) of LP.

Figure 6.

DIF photomicrograph showing IgM reactive large grouped globular (++) deposits (Civatte body) in the papillary dermis (anti-IgM, ×400)

Table 1.

Immunofluorescence patterns in skin biopsies of patients with lichen planus

Table 2.

Details of immunoreactant positivity at various locations in lichen planus

Discussion

The diagnostic importance of LP is related to its degree of frequency and incidence, its similarity with other diseases, its occasionally painful nature, and its possible connection with malignant tumors.[4] In our study, LP affected mainly individuals in 31-60 year age group while in other studies from India, the most commonly affected age group was 31-40.[5,6,7] It affected both sexes, with a minor female predominance in accordance with the previous studies.[5,6,7,8] Most patients presented with polygonal papules with pruritus within an average of 6 months of onset of the disease. Apart from distribution of lesions on trunk, extremities, and buccal mucosa, an occasional involvement of nails and scalp was also noted. The incidence of nail involvement has been found to vary from nil to 6.4% in various Indian studies.[5,6,7] Classical LP was the most common clinical variant, followed by hypertrophic lichen planus. Clinico-histopathological discrepancies were observed in 3 patients only where a clinical possibility other than LP (i.e., dermatomyositis, bullous pemphigoid, and pyostomatitis vegetans) was considered.

Most common drugs related to this disease as causative agents are gold salts, beta-blockers, anti-malarials, thiazide diuretics, furosemide, spironolactone, penicillamine, and hypoglycemic drugs such as metformin.[9] Allergic reactions to amalgam (metal alloys) dental restorations (fillings) may contribute to the oral lesions identical to oral lichen planus lesions both clinically as well as histologically. A systematic review has demonstrated that many of the lesions resolved after the restorations were replaced.[10] In our study, the most common offenders precipitating LP were the beta-blockers.

Focusing on the histological findings, hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer of the epidermis and the band-like sub-epidermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate was identified in 100% of the patients, a finding that is corroborated by other authors.[11] This, along with the absence of epithelial dysplasia, constitutes the 3 typical histological criteria of LP. We found CBs in 29% cases, which is an important feature of LP. The CBs represent necrotic keratinocytes, measure about 20 μm in diameter and have a homogeneous, eosinophilic appearance. Other diseases where CB's can be found include any interface dermatitis, in which damage to the basal cells occurs, i.e., lupus erythematosus, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), drug reactions, and in inflamed keratoses such as lichenoid actinic keratosis and lichen planus-like keratosis.[12] In LP, the number of necrotic keratinocytes may be so large that they are seen lying in clusters in the uppermost dermis in histology.[13] We observed such clusters in 4 cases of our study.

The DIF results showed positive findings in 55% of skin biopsies, which correspond to previously reported positive immunofluorescence findings in 37-97% of LP patients.[14,15,16] Any immunoreactant deposit at CBs plus shaggy fibrinogen deposition, whether alone or combined with other immunoreactants at DEJ, are among the most important findings on DIF favoring the diagnosis of LP.[16] Fibrinogen is the most common immunoreactant deposit (91-100%) seen at DEJ in LP. Other immunoglobulin viz. IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 deposition at DEJ ranges from 16-47%. We observed granular deposits of immunoreactants at DEJ in 7.8% cases only.[14,16] As fibrinogen was not included in the routine DIF staining protocol in our department, this might be one of the reasons that explain low prevalence of positive DIF findings at DEJ noted in this study cohort.

We observed immune deposits at CBs in 18/38 biopsies (including 11 cases who were positive for CBs on HPE), thus making DIF a more sensitive technique for detection of CBs. This fact re-emphasizes the importance of DIF in facilitating the diagnosis of LP. In the present series, the fluorescent CBs on DIF were most commonly seen with IgM (72%) followed by IgG (56%). Kulthanan et al. also reported the similar findings with IgM being the commonest immuno-reactant at CBs in 93% of biopsies.[14] Laskaris et al. showed that fibrin was most commonly found at CBs.[17]

However, all these DIF findings do not confirm the diagnosis of LP because they can be associated with other conditions. As mentioned above, although CBs can also be found occasionally in many other cutaneous disorders such as DLE, yet they are highly suggestive of LP if present in large numbers or arranged in clusters or groups.[15] CBs in LP lesions demonstrate a tendency to cluster in groups of 10 or more in the papillary dermis. This cluster formation on DIF may be useful in distinguishing LP from LE, because, in the latter condition, when CBs are present, they tend to exhibit a more linear arrangement. Moreover, between LP and DLE, immune deposits at CBs alone are seen more commonly in LP, whereas immune deposits at CBs plus DEJ and superficial blood vessel (SBV) are more common in DLE.[16] The results of DIF findings in this study were found to be similar to other studies with respect to detection of CBs, type of immunoreactant found on these CB as well as absence of DEJ and SBV deposits. An interesting feature in our study was presence of combinations of various types of immunoreactants at CBs that were detected in 50% cases and CBs involving more than 3 immunoreactants, which was seen in 22% cases. This finding is a unique phenomenon not described in other conditions and may be taken as another indicator for the diagnosis of LP. It should be noted that only a small number of biopsy specimens were obtained from each location, hence there was no statistically significant difference in the positive DIF yield between specimens derived from different sites.

In conclusion, cases with non-classical clinical presentation of LP as well as other similar-looking skin lesions are a diagnostic dilemma for dermatologists and dermato-pathologists. However, combination of clinical, histopathological as well as DIF findings can help in accurate categorization and proper management of these cases.

What is new?

There was no correlation found between the number and intensity of CBs with clinical variants of disease and also between the number of positive immunoreactants and clinical severity of the disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Mobini N, Toussaint S, Kamino H. Noninfectious erythematous, papular, and squamous siseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 180–214. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis FA. Histopathology of lichen planus based on analysis of one hundred biopsies. J Invest Dermatol. 1967;48:143–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.1967.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutism DF, Adam BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803–21. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Meij EH, Schepman KP, Smeele LE, Van der Wal JE, Bezemer PD, Van der Waal I. A review of the recent literature regarding malignant transformation of oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:307–10. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh OP, Kanwar AJ. Lichen planus in India-an appraisal of 441 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1976;15:752–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1976.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachhawa D, Kachhawa V, Kalla G, Gupta LP. A clinicoaetiological profile of 375 cases of lichen planus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:276–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichen Planus-a clinico-histopathological study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:193–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scully C, EI-Kom M. Lichen planus: Review and update on pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:431–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daoud MS, Pittellkow MR. Lichen planus. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 463–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Issa Y, Brunton PA, Glenny AM, Duxbury AJ. Healing of oral lichenoid lesions after replacing amalgam restorations: A systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:553–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Meij EH, Van der Waal I. Lack of clinicopathologic correlation in the diagnosis of oral lichen planus based on the presently available diagnostic criteria and suggestions for modifications. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:507–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grubauer G, Romani N, Kofler H, Stanzl U, Fritsch P, Hintner H. Apoptotic keratin bodies as autoantigen causing the production of IgM-anti-keratin intermediate filament autoantibodies. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;87:466–71. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12455510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camisa C, Neff JC, Olsen RG. Use of indirect immunofluorescence in the lupus erythematosus/lichen planus overlap syndrome: An additional diagnostic clue. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:1050–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Varothai S, Pinkaew S, Sutthipinittharm P. Direct immuno-fluorescence study in patients with lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1237–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu YH, Lin YC. Cytoid bodies in cutaneous direct immunofluorescence examination. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:481–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda P, Triwongwaranat D, Pinkaew S, Kulthanan K. Diagnostic significance of colloid body deposition in direct immunofluorescence. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:373–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.66583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskaris G, Sklavounou A, Angelopoulos A. Direct immunofluorescence in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;53:483–7. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]