Sir,

A 101-year-old Japanese housewife was referred to our department for treatment of a nodule on her left cheek. The nodule had a 3-year history and had enlarged rapidly within the past 3 months. She had consulted with a former dermatologist and was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by skin biopsy. She had no family history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. In an initial physical examination in our department, a skin-colored nodule measuring 16 mm with an eroded and crusted surface was seen on the left cheek [Figure 1a]. Small yellow-brown nodules and patches were also observed on the face, clinically consistent with seborrheic keratosis and lentigo senilis [Figure 1a]. However, actinic keratosis was not seen on the skin. Laboratory tests showed a decreased platelet count (88000/μl), mild anemia (hemoglobin 10.5 g/dl), and renal dysfunction (blood urea nitrogen, 39.7 mg/dl; creatinine, 1.54 mg/dl). However, neither liver nor heart disorders were present. Computed tomography scans of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed no distant metastasis. En bloc resection was performed under local anesthesia with a 6-mm margin from the periphery of the tumor, and the defect was covered with a full-thickness skin graft. Histopathologically, the tumor showed typical findings of cutaneous SCC with partial fatty tissue invasion [Figure 2a and b]. At the periphery of the tumor, atypical keratinocytes in the deeper portions of the epidermis and solar elastosis in the dermis were seen, consistent with actinic keratosis (AK) [Figure 2c]. We diagnosed this case as stage I SCC (T1N0M0) arising in an AK. The patient has shown no evidence of tumor recurrence and has had a good quality of life for over one and a half years postoperatively [Figure 1b].

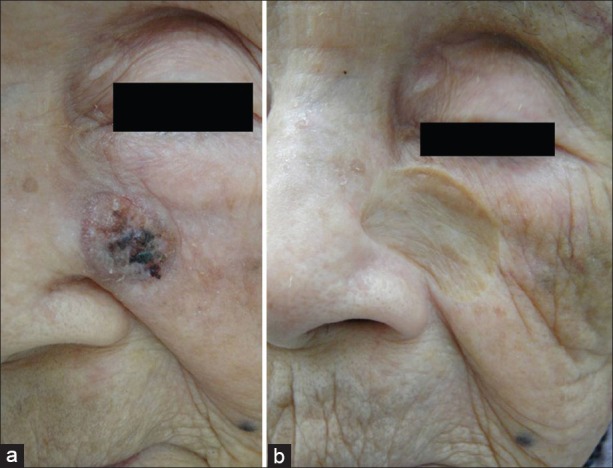

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs at first visit (a) and one and a half years postoperatively (b). (a) A skin-colored nodule measuring 16 mm with an eroded and crusted surface was present on the left cheek. Small yellow-brown nodules and patches were also observed on the face, clinically consistent with seborrheic keratosis and lentigo senilis (b) There is no evidence of tumor recurrence

Figure 2.

Histologic examination of SCC arising in an actinic keratosis (a). The tumor was well circumscribed and had partially invaded the fatty tissue (Hematoxylin–eosin (H and E), original magnification, × 13) (b). The tumor was an atypical squamoproliferative lesion composed of atypical, keratinizing tumor islands, and infiltrating strands with moderate to high grade nuclear atypia, consistent with SCC (H and E, original magnification × 100) (c). At the periphery of the tumor, atypical keratinocytes in the deeper portions of the epidermis and solar elastosis in the dermis were seen, consistent with actinic keratosis (H and E, original magnification × 200) (b) and (c) are high magnification images of the regions in (a) indicated by † and ‡, respectively

Cutaneous SCC is the second most common form of nonmelanoma skin cancer.[1] Over 72% of cases of SCC develop within AK or actinically damaged skin.[1] In the United Kingdom, a recent study of AK found an overall prevalence of 34% and 18% in men and women aged ≥70 years.[2] Life expectancy has increased in developed and advanced countries, and the life expectancy for Japanese women reached 86 years old in 2011. Therefore, the incidence of cutaneous SCC including SCC arising in AK may increase worldwide. However, to our knowledge, this report and that of Yoshida et al.[3] are the only two descriptions of cutaneous SCC in centenarian patients in the English language literature. In Yoshida et al.,[3] the patient was healthy without complications and the tumor was excised under general anesthesia, with repair of the defect using reconstruction with flaps. The patient in our case was considered eligible for surgery under local anesthesia. Safe doses of a local anesthetic could be used because the tumor size was small and neither liver nor heart disorders were detected.

The choice of appropriate treatment for cutaneous SCC is crucial in elderly patients with risk factors such as chronic splanchnopathies. However, advanced age alone does not seem to be a contraindication for surgery. In a case with no or minor complications, surgery may be the most reliable method for preventing metastasis and further enlargement of the tumor, and thus providing a better quality of life for elderly patients.

References

- 1.Samarasinghe V, Madan V. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:3–10. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.94323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn AG, Perkins W. Non-melanoma skin cancer and other epidermal skin tumours. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CS, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010. pp. 30–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida Y, Yamasaki A, Shiomi T, Suyama Y, Nakayama B, Yamamoto O. Ulcerative pigmented squamous cell carcinoma in a 101-year-old Japanese woman. J Dermatol. 2009;36:241–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]