Abstract

Background:

leishmaniasis infection might manifest as sarcoidosis; on the other hand, some evidences propose an association between sarcoidosis and leishmaniasis. Most of the times, it is impossible to discriminate idiopathic sarcoidosis from leishmaniasis by conventional histopathologic exam.

Aim:

We performed a cross-sectional study to examine the association of sarcoidosis with leishmaniasis in histopathologically diagnosed sarcoidal granuloma biopsy samples by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Materials and Methods:

We examined paraffin-embedded skin biopsy samples obtained from patients with clinical and histopathological diagnosis as naked sarcoidal granuloma, referred to Skin Research Center of Shaheed Beheshti Medical University from January 2001 to March 2010, in order to isolate Leishmania parasite. The samples were reassessed by an independent dermatopathologist. DNA extracted from all specimens was analyzed by the commercially available PCR kits (DNPTM Kit, CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran) to detect endemic Leishmania species, namely leishmania major (L. major).

Results:

L. major was positive in PCR of Eight out of twenty-five examined samples.

Conclusion:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis may be misinterpreted as sarcoidosis; in endemic areas, when conventional methods fail to detect Leishmania parasite, PCR should be utilized in any granulomatous skin disease compatible with sarcoidosis, regardless of the clinical presentation or histopathological interpretation.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, Leishmania major, polymerase chain reaction, sarcoidal type granuloma, sarcoidosis

Introduction

What was known?

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease and the role of infectious microorganisms such as Mycobacterium leprae and Leishmania infantum in pathogenesis of sarcoidosis is investigated previously.

There is no study on the role or presence of Leishmania major, which is endemic in Iran.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease characterized by non-caseating epithelioid granuloma formation that may affect almost any organ, including lungs, liver, lymph nodes, eyes, and skin.[1] Several reports support the co-existence or even possible role of micro-organisms such as mycobacteria, especially cell-wall deficient forms like M. tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria and M. leprae,[2,3,4,5,6] Rickettsia helvetica,[7] Leishmania infantum,[8] and Brucella melitensis[9] in development of sarcoidosis; However, the exact etiology of sarcoidosis still remains unknown.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), caused by various species of Leishmania, is a self-limited lesion which may rarely progress to complicated clinical forms; CL is the endemic disease of tropical and sub-tropical parts of the world and it is observed with high incidence in different parts of Iran.[10,11]

CL typically presents as a red, crusted nodule and is usually limited to the face or extremities. The chronic lesions of CL generally consists of tuberculoid granulomas with very few organisms in the upper half of dermis that often impinge on the epidermis. Occasionally, this chronic form presents with unusual clinical and histopathological features, which are not akin to stereotypical characteristics of leishmaniasis and may lead to misdiagnosis in some cases. In. other words, in endemic area a granuloma that is reported as sarcoidosis might be an atypical presentation of leishmaniasis and requires further investigation.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) can detect leishmaniasis genome with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity.[12] We designed this study to investigate the association between sarcoid lesions and Leishmania major (L. major) by PCR technique in biopsy samples that were previously diagnosed as cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

The paraffin-embedded skin biopsy samples attained from cutaneous sarcoidosis patients referred between January 2001 and March 2009 were examined. The clinical impression of cutaneous sarcoidosis correlated with the histopathology diagnosis of naked sarcoidal type of granuloma in all cases. By investigating patients’ files, the samples with positive Mantoux test and simulating causes were excluded. Sarcoidal type granuloma was defined as well demarcated islands of epithelioid cells, containing few giant cells and sparse lymphocytic infiltrations at the margins of the epithelioid cell granuloma; therefore the nomenclature naked granuloma. Applying conventional diagnostic methods, all samples had been evaluated for detection of fungal, bacterial or parasite microorganisms formerly. Among these studies were the ones utilizing special staining such as Hematoxylin-Eosin (H & E), Gram, Giemsa, Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS), Ziehl-Neelsen, modified Ziehl-Neelsen, and Grocott's Methenamine Silver. Nonetheless, all the results were negative; moreover, a second pathologist re-examined the specimens and re-confirmed the diagnosis of naked sarcoid type granuloma in each specimen.

For purpose of our study, all the specimens were investigated for Leishmania parasite by PCR technique. This phase was performed in the Molecular Biology Research Centre of SBMU and thereafter, was repeated by the Biotechnology Research Centre of Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran. All the results were confirmed by the second authority.

DNA isolation from paraffin-embedded tissue

We performed DNA extraction from paraffin-embedded tissue samples according to High Yield DNA Purification kit's (DNPTM Kit, CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran) manual instructions. Paraffin tissue sections were cut with a microtome blade. For each sample, 2 ml of cleaning benzene followed by 3 ml of 2 M HCL were used to clean the microtome blade and all the other instruments. The samples were subsequently rinsed with 10 ml of sterile water. Thereafter, DNA isolation was performed according to DNPTM kit (Cinnagen, Tehran, Iran). Shortly after that, 500 μl of xylene was added to the tissue and in order to remove the paraffin, the specimen was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The xylene was then discarded and the tissue was washed three times by 30 ml of water. Consequently, 500 μl of lysis buffer (0.33M sucrose, 20 mM Tris, 5 mM MgC12 and 2% SDS) was added to the reaction and the sample was incubated for two more hours at 37°C. Next we boiled it for 10 minutes. The samples were centrifuged at 4000 RPM for 5 minutes. Finally the supernatant was transferred to another tube and DNA was precipitated by employing 2 ml of 0.3 M sodium acetate and 1 ml of absolute ethanol; then it was centrifuged at 12000 g for 10 minutes. The obtained pellet was washed with 2 ml of 70% ethanol and was suspended in 50 ml distilled water.

PCR analysis

Using specific molecular diagnostic kit from CinnaGen Co. (Leishmania sp. PCR Determination and Detection, CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran), we performed the PCR technique on the extracted DNA. This is PCR-based detection method developed using using parasite mitochondrial DNA (Kinetoplast DNA or K-DNA) as the target. 1 μl of the DNA was used in 50 μl reaction (1 μl Taq DNA polymerase, 5 μl of 10 × buffer, 2 μl of MgCl2, 2 μl of primers and 39μl of H2O). The PCR technique was carried out applying a step-up program as follows; initial denaturation for 3 minutes at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 minute, 62°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension of 7 minutes at 72°C. The negative control was PCR reaction without any DNA template. The positive control was provided in the kit. PCR product with 620bp band in 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis is considered as L. major. In addition, PCR detection kit for Mycobacteria was obtained from CinnaGen Co, Tehran, Iran. Extracted DNA was used as template for detection of mycobacteria as instructed in the kit.

Results

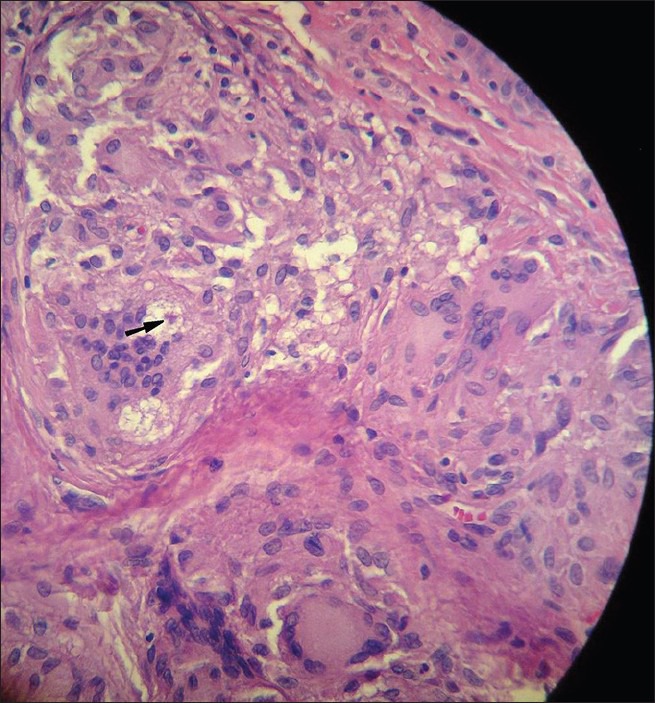

Thirty samples were examined and five were excluded: 3 due to positive Mantoux test and 2 due to inappropriateness of samples for analysis. Twenty-five paraffin-embedded blocks of skin biopsies were examined from patients with clinical diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis and histopathology of naked granuloma in light microscopy [Figure 1]; the samples were taken from 11 women and 14 men, ranging in age from 7 to 65, with a mean of 37.5 years.

Figure 1.

An asteroid body is shown within a multinucleated giant cell (Black arrow) (H and E, ×40)

Clinical descriptions of lesions are demonstrated in Table 1. From histological point of view, no caseating necrosis was seen in these samples, but in one specimen fibrinoid or coagulation necrosis was observed; a fine reticulum network surrounded the granulomas in five cases. Moreover, no microorganism was observed in specimens stained with conventional and specific staining methods.

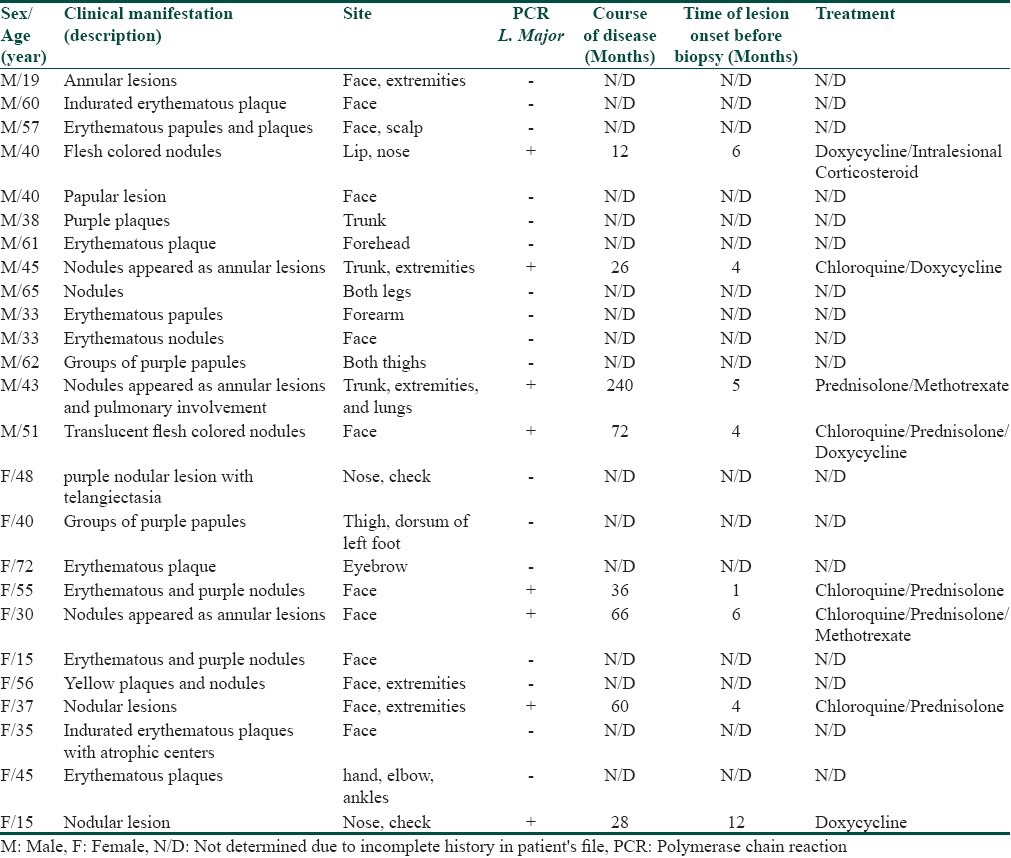

Table 1.

Description of skin lesions among all sarcoidal granuloma cases; along with their sex and age distribution

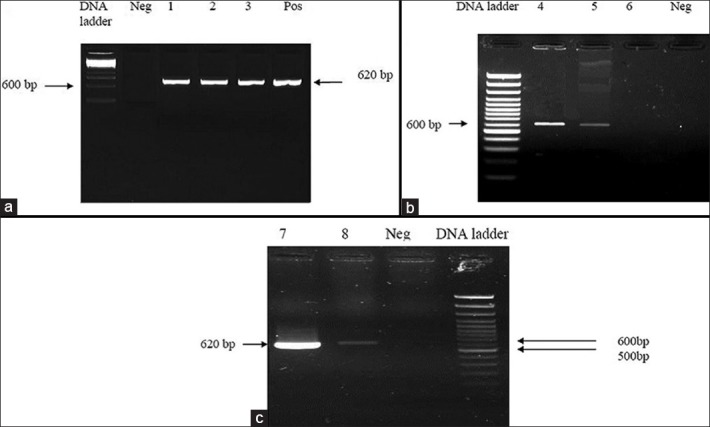

However, in eight out of twenty-five cases, PCR analysis on paraffin-embedded tissues revealed an amplification band, 620-bp, compatible with L. major [Figure 2]. As shown in the Figures 2a–c, the positive control is a standard strain provided by World Health Organization as L. major/RU. The negative control is the PCR reaction without any DNA template to eliminate chances of any false positive contamination. One of the two samples in Figure 2c (column 8) belongs to the skin biopsy of an individual who exhibited extra-cutaneous sarcoidosis. This patient had pulmonary involvement and coexistent diabetes mellitus. [Table 1- case #13] Also in this patient, PCR results were positive for L. major in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) as well as his skin biopsy, which is shown in the other sample in Figure 2c (column 7). One hypothesis holds mycobacterium tuberculosis responsible for this lesion. To rule out this possibility, the extracted DNA was amplified by MTB kit as defined in materials and methods section; however, only positive control of the kit was amplified. The sensitivity of the tests in this figures also demonstrates the fact that even with small amounts of DNA, we can obtain correct results due to the fact that k-DNA was employed as the amplification template.

Figure 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products from paraffin embedded samples. (a) 100 DNA ladder. Neg: Negative control A (No DNA template on the PCR reaction). Column #1. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 4; Column # 2. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 8; Column # 3. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 19; Pos: PCR amplification of the L. major standard strain. (b) 100 DNA ladder. Neg: Negative control A (No DNA template on the PCR reaction). Column # 4. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 14; Column # 5. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 18. Column # 6. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded from patient number 20. (c) 100 DNA ladder. Neg: Negative control A (No DNA template on the PCR reaction). Column # 7. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded BAL sample from patient number 13. Column # 8. PCR amplification of the paraffin embedded skin sample from patient number 13

Discussion

Sarcoidal granuloma (naked granuloma) may be found in a wide variety of diseases such as malignancies, local reaction to inert foreign substances and last but not least, infectious diseases; therefore, it should be always kept in mind that sarcoidosis is the diagnosis of exclusion.[13] Nowadays and with the advent of modern microbiological techniques, a great number of cases that were previously considered as sarcoidosis are understood to be associated with different infectious diseases.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] However, Leishmania genus has rarely been investigated in these conditions.[8,14,15]

Among various clinical manifestations of cutaneous leishmaniasis, chronic forms represent a diagnostic dilemma either in clinical setting or from a histological aspect; in fact, it is challenging to distinguish it from other simulating infectious diseases such as tuberculoid leprosy, lupus vulgaris, lupoid rosacea and granuloma annulare. Several reports have described isolation of Leishmania spp. from a significant number of both single and multiple atypical nodular skin lesions.[14,16] From histological point of view, these granulomas, considered “naked” or “sarcoidal granuloma”, are different from the classic tuberculoid granulomas observed in lupus vulgaris and chronic lupoid leishmaniasis, and normally would not be classified as granulomas caused by a living agent. Therefore, organism is either difficult to trace in those chronic lesions or is altogether absent. Until now, this feature has been reported frequently in association with various species of genus Leishmania.[14,16,17] In actual practice, unusual forms of CL may be misinterpreted by some clinicians as sarcoidosis, particularly in cases where Leishmania amastigotes are not observed microscopically. Moreover, this insidious form has always misled physicians into misdiagnosing it as other mimicking diseases, whereas the treatment strategy in some (e.g., sarcoidosis) is in complete contradiction to leishmaniasis treatment.

Leishmaniasis is an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients. Mucosal and cutaneous leishmaniasis has been previously reported in patients undergoing transplantations and pulmonary tuberculosis.[8] According to experimental studies in human CL, Leishmania infection is usually being controlled predominately by T-cell mediated mechanisms with a preferential Th1 pattern.[18] The occurrence of CL in these immunodeficient patients, therefore, may be due to inadequate cellular response.

In our study, methotrexate, an immunosuppressive agent, which preferentially inhibits cellular immunity, was used in two patients, in whom the lesions were found to be diffuse. (Patients number 13 and 19 in Table 1.) Further investigations revealed pulmonary involvement in one of the latter two cases. These evidences provide strong support for the concept that CL (especially diffuse form) was more likely related to the immunosuppressive effects of methotrexate than to sarcoidosis itself. Furthermore, another remarkable outcome of our study is that despite various types of lesions, even diffuse ones, all extracted Leishmania organisms belonged to L. major species. To the best of our knowledge, the phenomenon of diffuse leishmaniasis due to L. major has not been reported yet.

Since its advent, PCR has been proven to be an accurate laboratory test for rapid detection of numerous antigenic agents (including infectious agents and Leishmania in particular). Safaei et al. reported 92% sensitivity and 100% specificity for PCR in the context of positive histology with granulomatous inflammation in cutaneous leishmaniasis. In a quasi-contrast, they also achieved a PCR positive result in 24 out of 29 cases where the histological diagnosis failed to identify amastigotes (82.7% sensitivity).[12] In comparison with other diagnostic methods, sensitivity of PCR was higher and it has also been demonstrated that this discrepancy becomes more significant in chronic cases.[18] The reason we employed K-DNA PCR, is its due to highest sensitivity among other PCR-based kits utilized for Leishmania detection such as Internal Transcribed Spacer 1 PCR (ITS1 PCR) and splice leader mini-exon PCR (SLME PCR). Additionally, in lesions where the likelihood of detection of micro-organism is low, kDNA PCR has also proved to be a more illuminating technique. This has been achieved because of high abundance of mini circles per parasite (~10,000).[19]

Leishmaniasis is a worldwide disease, although about 90% of cutaneous forms of Leishmania infection occur in seven countries including Iran.[20] Based on several experiments, there are mainly two species of old-world Leishmania in this country, responsible for more than 90% of Iranian CL infection, including L. major and L. tropica.[21,22,23] Thus, considering their endemicity, geographical distribution and epidemiological features, we investigated our samples utilizing these Leishmania-specific PCR fragments.

In conclusion, we recommend that in endemic areas, any granulomatous skin disease compatible with sarcoidal type granuloma (naked granuloma), regardless of its clinical presentation and even histological appearance should be further investigated by the aid of PCR for Leishmania-specific DNA.

What is new?

Leishmania major might be found in some cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis

There might be some association between Leishmania major and sarcoidosis

PCR can be used to find the Leishmania species in patient with sarcoidosis in endemic area; the treatment of leishmaniasis may result in resolution of sarcoidosis lesions.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the kind consultation provided by Mr. Ali Khamesipour, PhD in Immunology and Dr. Soudabeh Givrad, M.D. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Marchell RM, Thiers B, Judson MA. Sarcoidosis. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz S, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 7 ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. 1484. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li N, Bajoghli A, Kubba A, Bhawan J. Identification of mycobacterial DNA in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:271–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almenoff PL, Johnson A, Lesser M, Mattman LH. Growth of acid fast L forms from the blood of patients with sarcoidosis. Thora×. 1996;51:530–3. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.5.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikonomopoulos JA, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos PV, Manolis EN, Kanavaros P, Rassidakis A, et al. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the detection of mycobacterial DNA in cases of tuberculosis and sarcoidosis. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:854–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdick AE, Hendi A, Elgart GW, Barquin L, Scollard DM. Hansen's disease in a patient with a history of sarcoidosis. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 2000;68:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osaki M, Adachi H, Gomyo Y, Yoshida H, Ito H. Detection of mycobacterial DNA in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens by duplex polymerase chain reaction: Application to histopathologic diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson K, Pahlson C, Lukinius A, Eriksson L, Nilsson L, Lindquist O. Presence of Rickettsia helvetica in granulomatous tissue from patients with sarcoidosis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1128–38. doi: 10.1086/339962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wermert D, Lamblin C, Wallaert B, Marty P, Leroy C. Pulmonary sarcoidosis with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:228–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pila-Perez R, Pila-Pelaez R, Paulino-Basulto M, del-Sol-Sosa JM. [Sarcoidosis and brucellosis: a strange and infrequent association] Gac Med Mex. 2003;139:160–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Public health aspects and control. Clin Dermatol. 1996;14:417–23. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowlati Y. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Clinical aspect. Clin Dermatol. 1996;14:425–31. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safaei A, Motazedian MH, Vasei M. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in histologically positive, suspicious and negative skin biopsies. Dermatology. 2002;205:18–24. doi: 10.1159/000063150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissler JC. Southwestern internal medicine conference: Sarcoidosis: Immunology and clinical management. Am J Med Sci. 1994;307:233–45. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boer A, Blodorn-Schlicht N, Wiebels D, Steinkraus V, Falk TM. Unusual histopathological features of cutaneous leishmaniasis identified by polymerase chain reaction specific for Leishmania on paraffin-embedded skin biopsies. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:815–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill PA. A case of granulomatous dermatitis: cutaneous leishmaniasis. Pathology. 1997;29:434–6. doi: 10.1080/00313029700169495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Convit J, Ulrich M, Perez M, Hung J, Castillo J, Rojas H, et al. Atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central America: possible interaction between infectious and environmental elements. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momeni AZ, Yotsumoto S, Mehregan DR, Mehregan AH, Mehregan DA, Aminjavaheri M, et al. Chronic lupoid leishmaniasis. Evaluation by polymerase chain reaction. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:198–202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.132.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell JP, Muller I, Louis JA. A role for Lyt-2+T cells in resistance to cutaneous leishmaniasis in immunized mice. J Immunol. 1989;142:2052–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bensoussan E, Nasereddin A, Jonas F, Schnur LF, Jaffe CL. Comparison of PCR assays for diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1435–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1435-1439.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashford RW, Desjeux P, Deraadt P. Estimation of population at risk of infection and number of cases of Leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1992;8:104–5. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Razavi M, Rezaei S, Kazemi B, Edrissian GH, et al. Identification of Leishmania species isolated from human cutaneous leishmaniasis, using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD-PCR) Iran J Public Health. 2004;33:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motazedian H, Noamanpoor B, Ardehali S. Characterization of Leishmania parasites isolated from provinces of the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8:338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadim A, Seyedi-Rashti M. A brief review of the epidemiology of various types of leishmaniasis in Iran. Acta Med Iran. 1971;14:99–106. [Google Scholar]