Abstract

Carbamazepine is a widely prescribed antiepileptic drug. Due to a lack of an intravenous formulation, its absolute bioavailability, absolute clearance, and half-life in patients at steady state have not been determined. We developed an intravenous, stable-labeled (SL) formulation in order to characterize carbamazepine pharmacokinetics in patients. Ninety-two patients received a 100 mg infusion of SL-carbamazepine as part of their morning dose. Blood samples were collected up to 96 hours after drug administration. Plasma drug concentrations were measured with LC-MS and concentration-time data were analyzed using a noncompartmental approach. Absolute clearance (L/hr/kg) was significantly lower in men (0.039±0.017) than women (0.049±0.018;p=0.007) and in African Americans (0.039±0.017) when compared to Caucasians (0.048±0.018;p=0.019). Half-life was significantly longer in men than women as well as in African Americans when compared to Caucasians. The absolute bioavailability was 0.78. Sex and racial differences in clearance may contribute to variable dosing requirements and clinical response.

Keywords: carbamazepine, pharmacokinetics, stable-labeled isotope, steady-state

INTRODUCTION

Carbamazepine, a commonly prescribed antiepileptic drug, is a first-line treatment for partial seizures, and is indicated for bipolar disorder and trigeminal neuralgia. Its use, however, is often limited by its complex pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and adverse effects. (1) (2) Carbamazepine is slowly absorbed (3) (4) (5) (6), moderately protein bound (65% to 85% to a combination of albumin and AAG), and exhibits an initial low clearance that increases two to three fold due to autoinduction. (4) (7) (8) Carbamazepine also has an active metabolite, carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide (carbamazepine-E) (9) (10) that possesses anticonvulsant activity and CNS toxicity similar to the parent compound. (11) (12) The major route of carbamazepine metabolism is through CYP3A4(13, 14), and, to a lesser degree, CYP3A5.(15)

Carbamazepine side effects including hyponatremia, cardiac conduction abnormalities, ataxia, nystagmus, and cognitive impairment may be due, in part, to its narrow therapeutic range, the presence of carbamazepine-E, and potential to interact with other drugs.(16) (1). Because an intravenous formulation was not available in previous studies, detailed carbamazepine pharmacokinetic information while patients are on maintenance therapy is lacking, especially within the therapeutic range (4-12 μg/mL). Rational dosing and monitoring strategies developed from research in patients under steady-state conditions are needed to better manage therapy and thus reduce the incidence of and minimize carbamazepine adverse reactions and improve seizure control. Simultaneous administration of intravenous and oral carbamazepine offers the best approach to attain this much-needed pharmacokinetic information.

Pairing orally administered drug with intravenously administered, stable-labeled (non-radioactive) isotopes of the same compound coupled with mass spectrometric analysis is a valuable tool for pharmacokinetic and bioavailability studies (17). This method involves co-administration of an intravenous stable isotope by replacing a portion of the patient's usual oral dose, permitting measurement of the absolute bioavailability, absolute clearance, distribution volume, and elimination half-life -- parameters that cannot usually be determined from oral dose studies. For antiepileptic drugs, it is the only method to rigorously characterize pharmacokinetics in patients under steady-state conditions because interruption of drug therapy, which would expose the individual to an increase risk of seizures, is contraindicated. Non steady-state studies, or those relying exclusively on data following oral administration, are limited because they do not fully characterize pharmacokinetics under clinically relevant conditions. Administration of injectable stable isotope formulations has been successfully used by our group and others to determine phenytoin pharmacokinetics (18, 19) (20) (21). The objective of this study was to investigate the pharmacokinetics of intravenous CBZ and the effect of sex and race on carbamazepine disposition during steady-state conditions..

RESULTS

Ninety-two (92) subjects were included in the pharmacokinetic analyses. Patient demographic information is shown in Table 1. The daily carbamazepine dose range (200-2400 mg/day) is representative of its clinical use (22). All subjects included in the analysis cohort completed the study per protocol.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Characteristics

| N | 92 |

|---|---|

| Males/Females | 45/47 |

| Age (yrs) | 41 (11) |

| Weight (kg) | 80.4 (20.1) |

| Daily CBZ dose (mg) | 819 (514) |

| Race (AA/As/CA) | 37/1/54 |

| CBZ formulation: Immediate/Extended release | 31/61 |

Values are presented as mean (standard deviation); CBZ, carbamazepine AA, African American; As, Asian; CA, Caucasian

The LC-MS assay readily distinguished intravenously administered SL-carbamazepine from non-labeled, orally administered immediate- and extended-release carbamazepine as is shown in Figures 1a and 1b, respectively. This representative plot also illustrates the log-linear decline of SL-carbamazepine while the unlabeled carbamazepine concentrations for this subject remained relatively constant, a feature characteristic of all subjects’ concentration-time data.

Figure 1.

a. A representative concentration-time curve for oral, immediate release carbamazepine (IR-CBZ) and stable-labeled carbamazepine (SL-CBZ) administered intravenously to a male on 400 mg/day (b.i.d) oral generic carbamazepine; Volume of distribution = 1.0 L/kg; Elimination half-life = 26.2 hrs.

b. A representative concentration-time curve for oral, extended release carbamazepine (ER-CBZ) and SL-CBZ administered intravenously to a male on 600 mg/day (b.i.d.) Tegretol XR; Volume of distribution = 1.1 L/kg; Elimination half-life = 35.1 hrs.

A summary of the carbamazepine pharmacokinetics is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of carbamazepine pharmacokinetic parameters

| TOTAL N=92 | MALE N=45 | FEMALE N=47 | AA N=37 | CA N=54 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41 (11) | 43 (11) | 39 (11) | 41 (11) | 42 (12) |

| Weight (kg) | 80.4 (20.1) | 88.8 (17.2) | 72.4 (19.5) | 80.5 (21.4) | 80.6 (19.5) |

| Dose/kg (mg) | 10.4 (6.1) | 9.7 (5.5) | 10.9 (6.6) | 9.9 (6.6) | 10.6 (6.1) |

| Cmax (SL); (ug/mL) | 1.99 (0.80) | 1.96 (0.87) | 2.02 (0.73) | 2.03 (0.86) | 1.97 (0.77) |

| Half-life (hr) | 20.0 (8.7) (7.8-53.4) | 22.7 (8.7)* | 17.5 (8.0) | 22.4 (8.1)** | 18.4 (8.8) |

| Clearance (L/hr) | 3.39 (1.22) | 3.44 (1.41) | 3.34 (1.02) | 2.94 (1.02) | 3.69 (1.27) |

| Cl (L/hr/kg) | 0.044 (0.018) | 0.039 (0.017)*** | 0.049 (0.018) | 0.039 (0.017)**** | 0.048 (0.018) |

| Vd (L) | 89.78 (32.5) | 102.19 (33.62) | 77.90 (26.65) | 90.17 (32.01) | 90.68 (34.01) |

| Vd/kg (L/kg) | 1.11 (0.26) | 1.15 (0.31) | 1.07 (0.20) | 1.12 (0.28) | 1.11 (0.25) |

| Bioavailability++ | 0.78 (0.24) (0.38-1.44) N=42 | 0.78 (0.23) N=20 | 0.78 (0.25) N=22 | 0.78 (0.25) N=15 | 0.78 (0.24) N=26 |

| Carbamazepine Cp0 (μg/mL) | 7.84 (3.11) | 8.14 (3.15) | 7.57 (3.07) | 7.62 (2.92) | 7.99 (3.24) |

| Carbamazepine-E Cp0 (μg/mL) | 1.23 (0.79) | 1.23 (0.78) | 1.23 (0.80) | 1.13 (0.71) | 1.29 (0.84) |

| Fμ (free fraction) | 0.26 (0.06) N=72 | 0.26 (0.06) N=36 | 0.25 (0.05) N=36 | 0.25 (0.07) N=35 | 0.26 (0.05) N=37 |

AA, African Americans; CA, Caucasians

p= 0.002

p=0.029

p=0.007

p=0.019

+values are reported as mean (standard deviation)

Bioavailability (F) was computed only on those subjects with a dosing interval of every 8 or every 12 hrs

Both clearance and clearance adjusted for weight (Cl) were highly variable, ranging from 0.871 to 7.345 L/hr and 0.010 to 0.095 L/hr/kg, respectively. The mean Cl in men (0.039±0.017 L/hr/kg) was lower (p = 0.007) than that of women (0.049± 0.018 L/hr/kg). Similarly, Cl was lower (p =0.019) in African Americans (0.039± 0.017 L/hr/kg) than for Caucasians (0.048±0.018 L/hr/kg). There was no interaction between sex and race (Figure 2). On average, Caucasian females had a 67% greater clearance adjusted for body weight than African American men. Multiple regression analysis revealed that sex and race accounted for 21.7% of the variance in Cl.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of mean weight adjusted clearance by sex and race.

Half-life

Carbamazepine half-life varied almost 7 fold, ranging from 7.8 to 53.4 hrs. The mean half- life for men (22.7 ± 8.7 hrs) was longer (p = 0.002) than that for women (17.5 ± 8.0 hrs). The half-life (22.4 ± 8.1 hrs) in African Americans was also longer than that for Caucasians (18.42 ± 8.79 hrs; p = 0.029). Twenty-six percent of subjects had a half life ≥ 24 hrs. As with Cl, there was no interaction between sex and race on carbamazepine half-life.

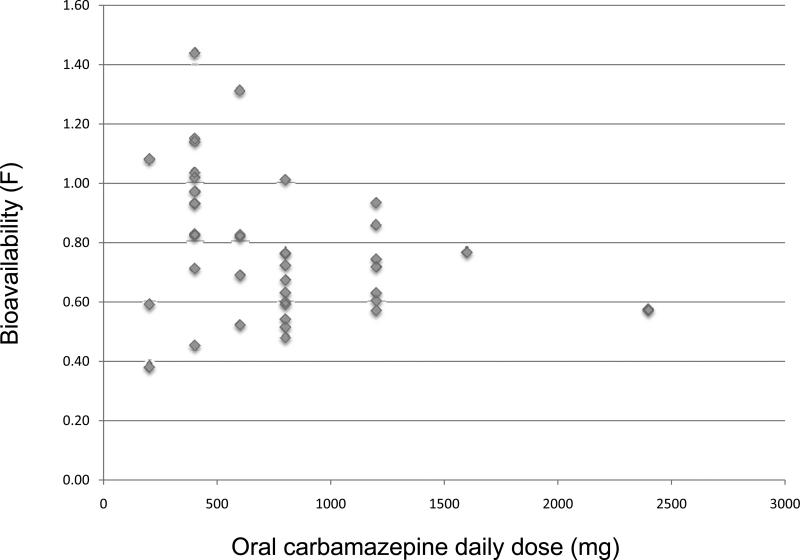

Bioavailability

The absolute bioavailability (F) was determined in a subset of 42 subjects (12 on immediate release and 30 on extended release carbamazepine). The mean and median fraction absorbed was 0.78 and 0.75 respectively, with almost a four-fold variability across subjects (0.38 to 1.44). There was no systematic difference in F either by sex, race or formulation. For the 12 subjects taking immediate release carbamazepine, the mean F=0.80±0.29 (range: 0.38-1.31) while the 30 subjects on extended release carbamazepine had a mean F=0.78±0.22 (range: 0.51-1.44). Moreover, there was no systematic difference in daily oral dose (mg/kg), trough carbamazepine and carbamazepine-E concentrations, or volume of distribution among patient groups.

DISCUSSION

This report provides new information on carbamazepine disposition in patients taking the medication under steady-state conditions. We found previously unreported sex and racial differences in Cl, elimination half lives greater than 24 hrs, and highly variable absorption.

Although the women in our study exhibited greater carbamazepine Cl than men, the influence of sex on the clearance of drugs metabolized via the CYP3A pathway remains an open question. (23) However our data, which isolates drug metabolism from absorption as well as active efflux/influx transport in the gut, is consistent with the observations that CYP3A substrates are eliminated more rapidly in women than men(24) (25) (26, 27). The mechanism for the greater CYP3A activity is incompletely understood and our study was not designed to elucidate the underlying processes. The sex difference in Cl averages 25%, indicating that women require a larger carbamazepine dose on a mg/kg basis than do men (28, 29) In clinical practice, carbamazepine therapy is usually prescribed as fixed doses, so the generally lower body weight of women compensates for their greater clearance. However, some women may require unusually large doses to attain the same plasma carbamazepine concentrations as men of comparable size.

Prior to beginning our study, several reports had been published describing polymorphisms in the gene encoding for CYP3A5. (30) There has also been speculation as to the influence of other CYP3A isoforms on the wide variability in pharmacokinetic parameters of many CYP3A substrates (31). Further, the polymorphisms are differentially expressed in Caucasians and African-Americans(24) (32, 33) with the latter more likely to carry the wild type form of 3A5, which confers greater enzymatic activity. Since carbamazepine is a substrate for 3A5, (15) (34) we hypothesized that African Americans would have a greater clearance than Caucasians. Contrary to our expectations, we found that the Cl was 23% lower in African Americans than Caucasians. It is possible that either unknown 3A5 SNPs are responsible for the unexpected reduction of metabolism via this isoenzyme, or there is reduced activity in other metabolizing enzymes.

Though we do not report data in this paper that directly address the role of genetics in producing the reported differences in Cl between Caucasians and African Americans, we considered other sources of variability that might have affected the mean Cl values for each population. Subjects were recruited from five sites, but 65% of the African-Americans were from Miami, where the majority (70%) of the patients were on an immediate release formulation of carbamazepine (generic or Tegretol). On the other hand, patients from both Emory and the Minnesota were largely (94% and 91% respectively) taking either Carbatrol or Tegretrol XR, both extended release formulations. Since all subjects were at steady-state, and hence fully induced, there is no obvious reason to postulate that the oral formulation should affect intravenous carbamazepine clearance. Thus, we stratified the groups according to site and calculated mean clearances of each. Subjects at Miami had a lower Cl (0.038 ± 0.015 L/hr/kg) than subjects from either Emory (0.052 ± 0.020 L/hr/kg) or the three sites in Minnesota (0.049 ± 0.019 L/hr/kg). Therefore, since formulation as well as race are nested in site, there may be other, non-genetic, factors influencing the unexpected difference in Cl between African Americans and Caucasians. Whatever the underlying mechanism(s), this finding warrants further investigation.

The mean elimination half-life in this study population averaged 20 hours, exceeding the range of 12-17 hours reported in the carbamazepine package insert for adult patients on monotherapy and substantially longer the estimate of 12 hrs reported by Eichelbaum (35) in 4 patients following 6 months of monotherapy. Similar to clearance, carbamazepine half-life displayed wide inter-subject variability with a large number of patients (26%) exhibiting a half-life of a full day or longer. There were, however, 16% of patients with half-lives of ≤ 12 hrs. The almost 7 fold range of elimination half lives we found in this group of patients on carbamazepine monotherapy further emphasizes the need to tailor therapy to patient response.

Despite sex and racial differences in both Cl and elimination half-life, we found no difference in absorption across any of the groups. While our average bioavailability is at the lower limit of that reported in the package insert, our results indicate there is large inter-individual variability in bioavailability. Since we withheld 100 mg of the morning oral dose, the resultant oral AUC(0-tau) slightly underestimates the actual AUC and, by extension, the true absolute carbamazepine bioavailability. The reduction in a single morning dose, which averaged 39%, likely had a modest effect (≈ 10%) on the oral AUC and estimation of bioavailability. However, a subsequent study in which patients on oral carbamazepine were given intravenous carbamazepine as replacement therapy found that the mean bioavailability was approximately 70% with comparable variability as seen in our study (36). The observation that some patients exhibited either very low absorption or had bioavailability values greater than 1 suggests that there may be substantial intra-patient variability in carbamazepine absorption. Poor water solubility and slow absorption may result in slowed and/or reduced carbamazepine absorption at certain times, followed by increased absorption of the current and recent doses depending on gastro-intestinal conditions. Wide intra-subject variability in plasma carbamazepine concentrations, consistent with relatively abrupt changes in absorption, has been reported by others (37).

Both bioavailability and clearance can have a profound effect on carbamazepine dosing requirements. The results from our study indicate that patients with poor absorption and very high clearances may have dosing requirements as much as 5 fold greater than those at the opposite extremes in order to attain similar plasma concentrations.

In conclusion, our study confirms that determination of pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers or after single doses may not accurately depict disposition under steady-state conditions. We found that during maintenance therapy carbamazepine absorption and clearance are highly variable and its elimination half-life is longer than previously reported. These factors should be considered when managing carbamazepine therapy. In particular, since Caucasian and female patients have, on the average, weight adjusted clearances that are 23-25% higher than their African Americans and males counterparts, respectively, they may require a compensatory increase in mg/kg dosing. In addition, the clinician must be aware of the possibility that poor bioavailability and/or very high clearances, rather than noncompliance, may be the culprit when carbamazepine plasma levels do not reflect the prescribed dose. Thus, the results of our study can be used to guide more effective use of carbamazepine, suggesting that rigorous characterization of other drugs during maintenance therapy might yield comparable information that can be clinically valuable.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were African American and Caucasian males and females 18-64 years of age with epilepsy taking carbamazepine. Patients were on either monotherapy or taking medications that do not interact with carbamazepine. Further, patients had to be on a stable maintenance carbamazepine regimen, that is, receiving continuous dosing over multiple months. No dosage adjustments, even minor changes, were allowed within two weeks prior to the first day of the study. Enrollment was stratified with the intention of studying equal numbers of women and men and Caucasians and African Americans. Those with significant medical problems who might not tolerate intravenous administration or those taking medications known to affect carbamazepine disposition were excluded from the study as were those who reported nonadherence to their carbamazepine therapy. Prior to enrollment, the project coordinator contacted subjects to discuss the protocol, confirm drug therapy, and review the consent form. The study was performed at the participating institutions’ General Clinical Research Centers or equivalent facilities.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards covering the five clinics from which subjects were recruited: University of Minnesota, MINCEP Epilepsy Care, Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Emory University, and the University of Miami. All subjects provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with FDA IND #60,722: Use of an Intravenous Stable-labeled Carbamazepine Isotope in Adult and Elderly Patients, 2000.

Intravenous, stable-labeled carbamazepine formulation

Stable-labeled carbamazepine [SL-carbamazepine} (5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine-5-13C, 15N-carboxamide) was synthesized by Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). The labels included 13C and 15N. The SL-carbamazepine was dissolved in a 22.5% w/v solution of HP-beta CD (Jansen) to yield a 50mg/mL solution of SL-carbamazepine. The intravenous formulation was prepared using good manufacturing practices by the University of Iowa Division of Pharmaceutical Services.

Study design

The study was carried out using an open label design. Patients were instructed to fast following dinner the night before the study and to hold all morning drug doses. On the morning of the study, patients were admitted to a research center, underwent brief medical and neurological exams, and provided seizure and medication histories. An indwelling catheter was then inserted in the left arm to facilitate blood sampling throughout the entire stay (either 12- or 24 hours). Blood samples were collected for genotyping, blood chemistries, BUN, CO2, glucose, creatinine, bilirubin, albumin, and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG). A second catheter was placed in the right arm for delivery of the study drug and was removed an hour after infusion.

A syringe was filled with 2mLs of the investigational formulation, weighed, and placed on an infusion pump. The 100mg SL-carbamazepine dose was infused over 10 minutes. Central nervous system toxicity and EKG were assessed by a neurologist (IL, JW, PP, GR) prior to, during, and 20 minutes after the infusion. Blood pressure and pulse were monitored every 2 minutes during infusion, every 15 minutes post-infusion, and then every 8 hours for 12- or 24 hours post infusion (depending on length of stay). A research nurse periodically examined the infusion site for irritation and extravagation and asked the patient about infusion site discomfort. The safety data from this study has previously been reported (38).

At the end of infusion, the syringe was weighed once again to confirm the amount of drug actually delivered. Immediately after receiving the SL-carbamazepine, the patient took his/her usual morning carbamazepine oral dose minus 100mg (as well as any other medications and/or supplements normally taken in the morning).

Blood sampling and drug analysis

Blood samples for determination of carbamazepine and carbamazepine-E were drawn prior to, and at 0.083, 0.25, 0.50, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after administration of SL-carbamazepine. Samples were immediately centrifuged and the plasma frozen until analysis. Urine samples were collected over 12 hours following administration of SL-carbamazepine and if the patient remained in the research facility, over 24 hours. Following the inpatient stay, the remaining blood samples were collected at either the inpatient site or a local clinic.

Plasma concentrations (bound and unbound) of the unlabeled and SL-carbamazepine and the unlabeled metabolites of carbamazepine (epoxide and diol) were measured using ESI and SIM modes of liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometry (Agilent 1100 LCMSD with Electrospray, model G1946). For each patient sample, both total and free carbamazepine were measured.

After spinning 1.0mL of each patient sample in an Amicon Centrifree filter assembly at 37°C to remove proteins along with the bound carbamazepine, the filter assembly containing plasma was centrifuged with a fixed angle rotor at 2000rpm for 60 minutes. If the ultrafiltrate volume was less than 500μL, the sample was spun for an additional 15-30 minutes. Patient samples were then prepared by adding 500μL of the plasma ultrafiltrate to 20μL of carbamazepine-d10 (internal standard: 250ug/mL solution), and extracted by adding 2.0mL ethyl acetate to each sample and vortexing for 20 seconds. Each tube was then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 2000 rpm and the organic layer was transferred to a clear test tube and dried on the Zymark evaporator at 30°C for 15 minutes. Samples were reconstituted with 200μL of mobile phase consisting of ammonium acetate buffer and methanol. The buffer was prepared with 3.85g ammonium acetate (reagent grade) in 1L water and the pH was adjusted to 4.7 using glacial acetic acid. After combining 1L buffer with 1 L methanol, the mixture was filtered and degassed prior to use. After the addition of the mobile phase, samples were filtered with a tuberculin syringe and a 0.45μM syringe filter, and transferred to pre-labeled, auto sampler vials.

The analytes were separated using a Zorbax LC8/LC18 column (3.0X150mm, 3.5μM; Agilent Technologies) at 40°C and the mobile phase (described above). The data were generated using Agilent ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) and quantified using deuterated carbamazepine-d10 internal standard, with a molecular weight of 246 (C/D/N Isotopes Inc, Quebec, Canada, cat #D-3542), and quadratic curves. The SL-carbamazepine was monitored at a molecular weight of 238 vs. 236 for unlabeled carbamazepine. Patient samples were run along with a 7-concentration standard curve (run in triplicate) (range: 0.5-20 μg/mL) and three quality control samples (low, medium and high, also run in triplicate). Unextracted samples of carbamazepine and SL-carbamazepine were also run for every assay to determine if any there was any contribution of unlabeled carbamazepine from the SL-carbamazepine and vice versa. There was no contribution of unlabeled carbamazepine to the SL-carbamazepine. The contribution of SL- carbamazepine to unlabeled carbamazepine was approximately 1.5%, which is consistent with the amount of naturally occurring 13C. Each analytical run was corrected by the amount determined from that day's assay.

The method was validated in our laboratory and had a within-assay variability ≤ 5.0% for all standards and a between-assay variation <5% for all standards except for the lowest standard which was 14.5%. Accuracy ranged between 83.7% - 102.6% for all standards. Quality control samples were all within ≤10%.

Pharmacokinetic analyses

Both stable isotope and non-labeled carbamazepine concentration-time data were analyzed using the pharmacokinetic modeling program WinNonLin® 5.1 employing nonlinear regression and a noncompartmental model assuming first order absorption and elimination.

For each subject, the terminal log-linear phase of the SL-carbamazepine plasma concentration-time curve was identified and the elimination rate constant (ke) was determined by regression analysis based on at least 5 time points. The elimination half-life (t1/2) was then calculated from the following equation: t1/2 = ln2/ke.

The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) was calculated by means of the logarithmic trapezoidal rule with extrapolation to infinity [AUC(0-∞)] for the intravenous SL-carbamazepine using ke. The logarithmic trapezoidal rule was also used to calculate the AUCoral(0-tau). Values for absolute plasma clearance and volume of distribution (Vd) of SL-carbamazepine were calculated by noncompartmental methods as follows: Clearance = Dose/AUCINF_obs and Vd = Dose/(keAUCINF_obs). Values for free fraction (Fμ) were calculated as: free carbamazepine/total carbamazepine.

The absolute bioavailability (F) of oral carbamazepine was estimated from the data of 42 subjects who were taking a fixed dose per dosing interval of oral carbamazepine either every 8 or 12 hours. F was calculated using the following equation:

Statistical analysis

The effects of sex and race on elimination half-life, clearance adjusted for weight (L/hr/kg) and Vd (L) were examined using a univariate analysis of variance (SPSS, v.14) A p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Figure 3.

Distribution of carbamazepine bioavailability in relation to daily oral carbamazepine dose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorder and Stroke grants P50 NS16308 (I.E.L. & J.C.C. co-PIs) and K 01 NS050309 (S.E.M.)

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

I.E.L., J.C.C. & A.K.B. have a royalty agreement with Lundbeck Inc. related to the development of intravenous carbamazepine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patsalos PN, Perucca E. Clinically important drug interactions in epilepsy: general features and interactions between antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:347–356. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsay RE, et al. Carbamazepine metabolism in humans: effect of concurrent anticonvulsant therapy. Ther. Drug Monit. 1990;12:235–241. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy RH, Lockard JS, Green JR, Friel P, Martis L. Pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine in monkeys following intravenous and oral administration. J. Pharm. Sci. 1975;64:302–307. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600640224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichelbaum M, Ekbom K, Bertilsson L, Ringberger VA, Rane A. Plasma kinetics of carbamazepine and its epoxide metabolite in man after single and multiple doses. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1975;8:337–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00562659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawlins MD, Collste P, Bertilsson L, Palmer L. Distribution and elimination kinetics of carbamazepine in man. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1975;8:91–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00561556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geradin AP, Abadie FV, Campestrini JA, Theobald W. Pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine in normal humans after single and repeated oral doses. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1976;4:521–535. doi: 10.1007/BF01064556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitlick WH, Levy RH. Time-dependent kinetics I: Exponential autoinduction of carbamazepine in monkeys. J. Pharm. Sci. 1977;66:647–649. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600660511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertilsson L, Hojer B, Tybring G, Osterloh J, Rane A. Autoinduction of carbamazepine metabolism in children examined by a stable isotope technique. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1980;27:83–88. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1980.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomson T, Almkvist O, Nilsson BY, Svensson JO, Bertilsson L. Carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide in epilepsy. A pilot study. Arch. Neurol. 1990;47:888–892. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530080072013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faigle J, Feldmann K. Pharmacokinetic data of carbamazepine and its major metabolites in man. In: Schneider H, D.J., Gardner-Thorpe C, et al., editors. Clinical pharmacology of antiepileptic drugs. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1975. pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgeois BF, Wad N. Carbamazepine-10,11-diol steady-state serum levels and renal excretion during carbamazepine therapy in adults and children. Ther. Drug Monit. 1984;6:259–265. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albright PS, Bruni J. Effects of carbamazepine and its epoxide metabolite on amygdala-kindled seizures in rats. Neurology. 1984;34:1383–1386. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.10.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr BM, et al. Human liver carbamazepine metabolism. Role of CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 in 10,11-epoxide formation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:1969–1979. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hata M, et al. An epoxidation mechanism of carbamazepine by CYP3A4. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5134–5148. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, et al. Evidence of significant contribution from CYP3A5 to hepatic drug metabolism. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:1434–1445. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patsalos PN, Stephenson TJ, Krishna S, Elyas AA, Lascelles PT, Wiles CM. Side-effects induced by carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide. Lancet. 1985;2:1432. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baillie TA. The use of stable isotopes in pharmacological research. Pharmacol. Rev. 1981;33:81–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne TR, et al. Studies with stable isotopes III: Pharmacokinetics of tracer doses of drug. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1985;25:59–63. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1985.tb02801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Browne TR. Stable isotopes in pharmacology studies: present and future. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1986;26:485–489. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1986.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browne TR. Stable isotopes in clinical pharmacokinetic investigations. Advantages and disadvantages. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1990;18:423–433. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199018060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn JE, et al. Phenytoin half-life and clearance during maintenance therapy in adults and elderly patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;71:38–43. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316392.55784.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loiseau P. Clinical efficacy and use in epilepsy. In: Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, Perucca E, editors. Antiepileptic Drugs Fifth edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL. ender has a small but statistically significant effect on clearance of CYP3A substrate drugs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;48:1350–1355. doi: 10.1177/0091270008323754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diczfalusy U, et al. 4Beta-hydroxycholesterol is a new endogenous CYP3A marker: relationship to CYP3A5 genotype, quinine 3-hydroxylation and sex in Koreans, Swedes and Tanzanians. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2008;18:201–208. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f50ee9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris RZ, Benet LZ, Schwartz JB. Gender effects in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Drugs. 1995;50:222–239. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu B, et al. The distribution and gender difference of CYP3A activity in Chinese subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;55:264–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz JB. The influence of sex on pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:107–121. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meibohm B, Beierle I, Derendorf H. How important are gender differences in pharmacokinetics? Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:329–342. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svinarov DA, Pippenger CE. Relationships between carbamazepine-diol, carbamazepine-epoxide, and carbamazepine total and free steady-state concentrations in epileptic patients: the influence of age, sex, and comedication. Ther. Drug Monit. 1996;18:660–665. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuehl P, et al. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nature genetics. 2001;27:383–391. doi: 10.1038/86882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mesdjian E, et al. Metabolism of carbamazepine by CYP3A6: a model for in vitro drug interactions studies. Life Sci. 1999;64:827–835. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamba JK, et al. Common allelic variants of cytochrome P4503A4 and their prevalence in different populations. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:121–132. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy JN, et al. CYP3A5 genetic polymorphisms in different ethnic populations. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:884–887. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.003822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thummel KE, Wilkinson GR. In vitro and in vivo drug interactions involving human CYP3A. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;38:389–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eichelbaum M, Kothe KW, Hoffmann F, von Unruh GE. Use of stable labelled carbamazepine to study its kinetics during chronic carbamazepine treatment. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1982;23:241–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00547561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walzer M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous carbamazepine in adult patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49:460–460. doi: 10.1111/epi.13012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leppik IE, Conway JM, Strege MA, Birnbaum AK. Intra-individual variability of carbamazepine and valproic acid serum concentrations in elderly nursing home residents. Neurology. 2010;74:A121–122. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conway JM, et al. Safety of an IV formulation of carbamazepine. Epilepsy Res. 2009;84:242–244. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]