Careful modulation of protein concentration is crucial in a variety of biological processes. For example, concentration of hnRNPA1 protein plays an critical role in controlling the isoform-selective expression of pyruvate kinase M1 or M2 through mutually exclusive mRNA splicing,[1] and the abundance of tumor suppressor p53 is elevated under stressed condition, enabling the cells to initiate various cellular responses.[2] Therefore, tools that can precisely control protein concentration in living cells are valuable for investigating the contribution of cellular protein levels to their function.[3] One of the most successful strategies towards this goal relies on protein destabilization domains (DD). Under normal conditions, a DD will be rapidly degraded by the proteasome. However, the same DD can be stabilized or “shielded” in a stoichiometric complex with a small-molecule, enabling dose-dependent control of its concentration. This process has been exploited by several labs to posttranslationally control the expression levels of proteins in vitro as well as in vivo, exemplified by work by the Wandless lab, which used a synthetic ligand Shld1 to control the stability of a proteins genetically fused to an FKBP-based DD (FKBP*, FKBP F36V, L106P).[4–8] Although these technologies are powerful and generalizable, they result in a permanent fusion of the protein of interest to the DD, which can affect its biological activity and complicate any results.

To address this issue, we previously reported a complementary strategy, termed traceless shielding (TShld), in which the protein of interest is released in its native form.[9,10] The TShld system contained two constructs (Figure 1A). The first construct consisted of FRB, a small domain of the mTOR protein, fused to a mutant (I13G) of the N-terminal fragment of ubiquitin (UbN, residues 1–37). The second construct had the following architecture: the DD (FKBP*) followed by the C-terminal fragment of ubiquitin (UbC, residues 35–76) and a protein of interest [e.g., green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a model]. To enable the rapid generation of stably transformed cell line, we encoded the two constructs into a single plasmid by using a viral “self-cleaving” 2A peptide that induces a cotranslational cleavage between the two proteins.[11,12]. Addition of rapamycin stabilized the FKBP*-UbC-GFP construct, which would otherwise be degraded by the proteasome, and subsequently recruited FRB-UbN construct, facilitating the complementation between UbN and UbC and dose-dependent release of the protein of interest from the DD by endogenous ubiquitin hydrolases (Figure 1B). While this system was able to successfully control the concentration of different proteins in their native form, we only observed a modest dynamic range of 5- to 7-fold, due to high background levels of non-degraded protein.

Figure 1.

TShld system. A) Architecture of TShld system. B) Design of TShld system. Under normal conditions, the FKBP* destabilizing domain results in proteasomal degradation of the fusion protein containing the protein of interest (POI). Upon addition of rapamycin, FKBP* is stablized and FRB-UbN is recruited, causing complementation with UbC and release of the protein of interest.

Here, we describe an optimized protein concentration control system that retains the traceless features of TShld but utilizes two tiers of small-molecule control to set protein concentration in living cells. Specifically, we placed level of TShld transcription under the control of doxycycline using a tetracycline-responsive promoter (Tet-On) to create TTShld. Using three concentrations of doxycyline in combination with a range of rapamycin concentrations resulted in a 130-fold range of GFP levels as a model protein. Notably, in this experiment, we observed that induced dimerization of UbN and UbC using rapamycin was not required for ubiquitin complementation and release of GFP. Therefore, we next demonstrated that rapamycin could be replaced with either FK506 or Shld1 to achieve a 87- and 56-fold range of GFP concentrations, respectively. All three small-molecules display good linearity with respect to the amounts of shielded protein across the entire range of concentrations, and the system is generalizable to other proteins of interest. These experiments provide the first protein-concentration control system that results in both a wide-range of protein concentrations and proteins free from engineered fusion constructs.

To improve the dynamic range of the TShld system, we added a second tier of small-molecule control: the Retro-X Tet-On Advanced Inducible Expression system (Clontech), in which the transcription level of gene of interest can be controlled by adjusting the concentration of the system’s inducer, doxycycline. For the ease of quantifying protein concentration, the green fluorescence protein (GFP) was selected as our model protein of interest. We cloned TShld-GFP construct into Retro-X Tet-On Advanced Vector, termed Tet-On TShld-GFP (TTShld GFP). Commercially available Tet-On HEK and HeLa cells were then stably transfected with TTShld-GFP using amphotropic retroviral infection. To confirm shielding and release of GFP, the HEK cells were treated with doxycycline (1000 ng/mL) and rapamycin (500 nM) or water and DMSO vehicles for 48 hours. Western blotting showed that a significant amount of GFP was released from the system only in the treated cells (Figure 2A). Notably, we did not observe any uncleaved T2A protein or full-length FKBP*-UbC-GFP. Next, we ask if the amount of GFP released from the system will be dose-dependent on both the doxycycline and rapamycin. Towards this end, stably transfected HEK and HeLa cells were treated with a combination of three different concentrations of doxycycline (0, 50, 1000 ng/mL) and three different concentrations of rapamycin (0, 50, 500 nM). Analysis by western blotting showed that the amount of GFP released from the system was dose dependent upon the two small molecules (Figure 2B and Figure S1). Again, no uncleaved T2A protein was detected.

Figure 2.

Analysis of TTShld-GFP in stably transformed cells. A) TTShld-GFP HEK cells were treated with doxycycline (1000 ng/mL) and rapamycin (500 nM) or water and DMSO vehicles for 48 hours and analyzed by Western blotting (FRB-UbN: anti-FLAG, FKBP*-UbC-GFP and GFP: anti-HA) B) TTShld-GFP HEK cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of doxycycline and rapamycin for 48 hours before analyzed by Western blotting. C) TTShld-GFP HEK cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of doxycycline and FK506 for 48 hours before Western blotting. D) TTShld(F36V)-GFP expressing HEK cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of doxycycline and Shld1 for 48 hours and then analyzed by Western blot.

Intriguingly, we observed the release of GFP from the system in the absence of rapamycin when the cells were treated with doxycycline alone (Figure 2B). Moreover, the amount of GFP released was dose-dependent on the concentration of doxycycline. Taken together, these data support a model where rapamycin-induced co-localization of the ubiquitin fragments (i.e., UbN and UbC) is not absolutely required for their complementation and GFP release. To test if this is the case, TTShld-GFP expressing HEK cells were treated with the same concentration of doxycycline (0, 50, 1000 ng/mL) and three different concentrations of FK-506 (0, 50, 500 nM), which will bind-to and stabilize FKBP* but not recruit FRB[13,14]. Analysis by western blotting (Figure 2C) showed that GFP was released in a similar dose-dependent manner compared to the cells that were treated with rapamycin (Figure 2B). This demonstrates that the rate of ubiquitin self-complementation is in large-part driven by the cellular concentrations of UbN and UbC and not by the rapamycin-mediated physical interaction between FKBP* and FRB. Importantly, this suggests that rapamycin and FK506, which both have endogenous cellular targets that could produce confounding biological effects in a protein concentration experiment.[15–17], could be replaced with the orthogonal small-molecule Shld1.[5] To test this possibility, we introduced a F36V mutation into the FKBP*, enabling the binding of Shld1 and subsequent stabilization of FKBP* and used retroviral transfection to introduce TTShld(F36V)-GFP into Tet-On HeK cells. We then treated these cells with a combination of three different concentrations of doxycycline (0, 50, 1000 ng/mL) and four different concentrations of Shld1 (0, 50, 500, 1000 nM). Analysis by western blotting demonstrated that the GFP was again released in a dose dependent manner with no observable uncleaved T2A protein or full-length FKBP*-UbC-GFP (Figure 2D).

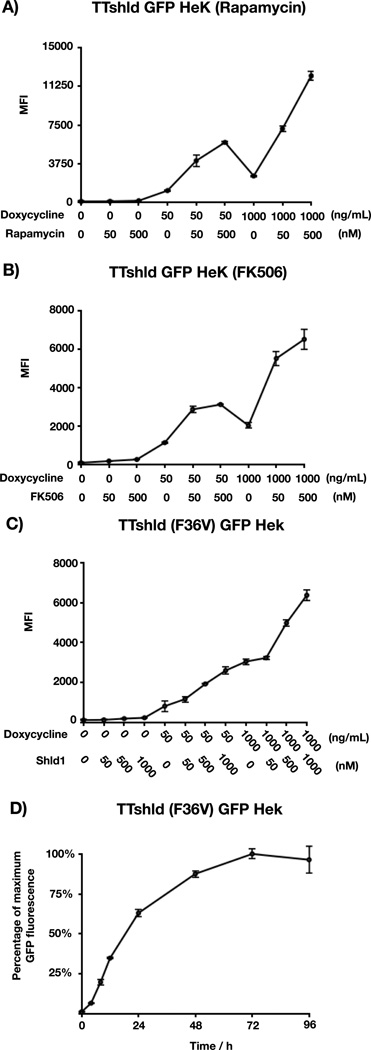

Next, we performed flow cytometry to quantitatively measure GFP concentration and to compare the different FKBP stabilizing small molecules (rapamycin, FK506, and Shld1). In combination with three concentrations of doxycycline, rapamycin precisely controlled the fluorescence intensity of GFP, measured by flow cytometry, in HEK cells with a dynamic range of 130-fold, whereas FK-506 in the same cell-line gave a dynamic range of 87-fold (Figure 3A and B). This supports our conclusion that ubiquitin complementation is driven by the concentrations of UbN and UbC but also demonstrates that rapamycin-induced physical proximity can further drive GFP release. Treating Tet-On HEK cells that stably express TTShld(F36V)-GFP with a range of concentrations of doxycycline and Shld1 resulted in GFP expression over a 56-fold dynamic range (Figure 3C). Because this stable cell-line is necessarily different from the TTShld cell-line (i.e., it contains the F36V mutation), it may have inherent differences in absolute transgene expression. Therefore, to compare the linearity of our control of GFP concentration, we normalized the highest GFP expression level within the two cell-lines. Among three FKBP-stabilizing molecules, Shld1 gave the most linear control of GFP concentration (Data not shown). Therefore, we decided to investigate the kinetics of GFP expression using these cells. Accordingly, we treated the cells with 1000 ng/mL doxycycline and 1 mM Shld1 for different amounts of time before analysis by flow cytometry (Figure 3D). GFP expression was observed as early as 4 hours and plateaued at 72, consistent with transcriptional control.

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of TTShld-GFP A & B) TTShld-GFP HEK cells were treated with doxycycline and rapamycin or FK-506 for the indicated concentrations for 48 hours and GFP fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry. C) TTShld(F36V)-GFP HEK cells were treated with doxycycline and Shld1 for the indicated concentration before flow cytometry analysis. D) TTShld(F36V)-GFP HEK cells were treated with doxycycline (1000 ng/mL) and Shld1 (1000 nM) for the indicated lengths of time before flow cytometry analysis. All experiments were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation; MFI: mean fluorescence intensity.

Finally, to explore the generality of the TTShld(F36V) system, we analyzed two additional proteins of interest. We generated Tet-On HeLa cells that stably express either pyruvate kinase M2 or caspase-3 under control of the TTShld(F36V) system by retroviral infection. These cell-lines were treated with 12 different concentration combinations of doxycycline (0, 50, 1000 ng/mL) and Shld1 (0, 50, 500, 1000 nM) for 48 hours and analyzed by western blotting (Figure 4). In both cases we observed good linear expression level of the protein of interest across the whole spectrum of two small molecules.

Figure 4.

Analysis of TTShld(F36V)-PKM2 and TTShld(F36V)-Caspase-3. HeLa cell-lines stably expressing either construct were treated with indicated concentration of doxycycline and Shld1 for 48 hours before Western blotting analysis.

In summary, we have upgraded the protein-concentration tuneability of the TShld system by placing it under an additional level of small-molecule control at the transcription level, termed TTShld. Using GFP as a model protein, TTShld system gives us a 130-fold range access of protein abundance when using rapamycin as the FKBP*-stabilizing molecule. Interestingly, we found that formation of the FKBP*-rapamycin-FRB ternary complex and coincident co-localization of UbN and UbC was not absolutely required for ubiquitin complementation and release of GFP. Instead, treatment of cells expressing the TTShld system with FK506 instead of ramapycin, resulted in a 87-fold range of GFP concentrations, demonstrating that UbN and UbC can self-complement in a concentration dependent fashion. This contradicts several studies that have used the split-ubiquitin technology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to identify and characterize protein-protein interactions.[18–22] We attribute this difference to the inherent differences between mammalian and yeast cells. Specifically, the higher growth temperature of mammalian cells, 37 ° compared to yeast, 30 °, could kinetically allow for ubiquitin self-complementation. Additionally, mammalian cells may express a molecular chaperone that facilitates split-ubiquitin folding. In either case, this concentration-dependent self-complementation allowed us to introduce a F36V mutation in FKBP* to make use of the non-toxic Shld1 as the FKBP* stabilizing molecule,[5] yielding a 56-fold range of GFP concentrations. Therefore, the TTShld system can be applied to systems where inhibition of the mTOR kinase or calcineurin by rapamycin or FK506, respectively, should be avoided.[15–17] The TTShld system has a greatly improved dynamic-range compared to our previously reported system.[9], and we are confident that the traceless feature will be attractive for the elucidation of the consequences of protein concentration in cell biology.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Chen M, David CJ, Manley JL. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:346–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bargonetti J, Manfredi JJ. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:86–91. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banaszynski L, Wandless T. Chem Biol. 2006;13:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu BW, Banaszynski LA, Chen L-C, Wandless TJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5941–5944. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banaszynski L, Chen L, Maynard-Smith L, Ooi A, Wandless T. Cell. 2006;126:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stankunas K, Bayle JH, Havranek JJ, Wandless TJ, Baker D, Crabtree GR, Gestwicki JE. Chem Bio Chem. 2007;8:1162–1169. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banaszynski LA, Sellmyer MA, Contag CH, Wandless TJ, Thorne SH. Nat Med. 2008;14:1123–1127. doi: 10.1038/nm.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwamoto M, Björklund T, Lundberg C, Kirik D, Wandless TJ. Chem Biol. 2010;17:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau HD, Yaegashi J, Zaro BW, Pratt MR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:8458–8461. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratt MR, Schwartz EC, Muir TW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11209–11214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700816104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DAA. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holst J, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Vignali DAA. Nat Meth. 2006;3:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nmeth858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohler J, Bertozzi C. Chem Biol. 2003;10:1303–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Graffenried CL, Laughlin ST, Kohler JJ, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16715–16720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403681101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EJ, Beal PA, Keith CT, Chen J, Shin TB, Schreiber SL. Nature. 1995;377:441–446. doi: 10.1038/377441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corradetti MN, Guan K-L. Oncogene. 2006;25:6347–6360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnsson N, Varshavsky A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stagljar I, Korostensky C, Johnsson N, te Heesen S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5187–5192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan A, Lennarz W. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3121–3124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kittanakom S, Chuk M, Wong V, Snyder J, Edmonds D, Lydakis A, Zhang Z, Auerbach D, Stagljar I. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;548:247–271. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-540-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mockli N, Deplazes A, Hassa P, Zhang Z, Peter M, Hottiger M, Stagljar I, Auerbach D. BioTechniques. 2007;42:725–730. doi: 10.2144/000112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.