Abstract

Objective

Evaluate three methods of integrating interventions for depression (Adolescent Coping With Depression Course; CWD) and substance use disorders (Functional Family Therapy; FFT), examining (1) treatment sequence effects on substance use and depression outcomes, and (2) whether the presence of major depressive disorder (MDD) moderated effects.

Method

170 adolescents (ages 13–18; 22% female; 61% non-Hispanic white) with comorbid depressive disorder (54% MDD, 18% dysthymia) and substance use disorders were randomized to: (1) FFT followed by CWD (FFT/CWD), (2) CWD followed by FFT (CWD/FFT), or (3) Coordinated FFT and CWD (CT). Acute treatment (24 treatment sessions provided over 20 weeks), 6- and 12-month follow-up effects are presented for substance use (% days substance use; Timeline Followback) and depression (Children’s’ Depression Rating Scale-Revised).

Results

FFT/CWD achieved better substance use outcomes than CT at post-treatment, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups; substance use effects for CWD/FFT were intermediate. For participants with baseline MDD, the CWD/FFT sequence resulted in lower substance use than either FFT/CWD or CT. Depressive symptoms decreased significantly in all three treatment sequences with no evidence of differential effectiveness during or following treatment. Attendance was lower for the second of both sequenced interventions. A large proportion of the sample received treatment outside the study, which predicted better outcomes in the follow-up.

Conclusions

Depression reductions occurred early in all three treatment sequences. Of the examined treatment sequences, FFT/CWD appeared most efficacious for substance use reductions, but addressing depression early in treatment may improve substance use outcomes in the presence of MDD.

Keywords: comorbidity, depression, substance use disorders, adolescents, treatment

Depression and substance use disorders (SUDs) are among the most prevalent disorders of adolescence, and rates of comorbidity are high (Armstrong & Costello, 2002), which complicates the conceptualization and provision of treatment. The impact of comorbidity on SUD treatments has not been adequately studied and SUD relapse rates are high for depressed adolescents (e.g., Godley, Dennis, Godley, & Funk, 2004). Among adolescents with SUD, depression has been associated with more severe substance use (Warden et al., 2012) and higher SUD relapse (McCarthy et al., 2005; Waldron et al., 2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has improved longterm depressive and alcohol outcomes relative to usual care (Cornelius et al., 2011) and CBT plus fluoxetine reduced depressive symptoms (but not substance use) relative to CBT plus placebo (Riggs et al., 2007) in youth with both disorders. The present study evaluated three methods of delivering two interventions for adolescent depression and SUDs: (1) the Adolescent Coping With Depression course (CWD; Clarke et al., 1990), and (2) Functional Family Therapy (FFT; Alexander & Parsons, 1982). The CWD, a cognitive-behavioral group intervention, has been found to be efficacious for depressive disorders, though comorbidity reduces its efficacy (Rohde et al., 2001). FFT is an empirically supported treatment for disruptive behaviors that has been adapted for SUD (Waldron & Turner, 2008). To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of psychosocial treatments for depression and SUDs. We examined (1) the effects of treatment sequence on substance use and depression, and (2) whether severe depression, as indicated by major depression, moderated the effects of treatment sequence.

Method

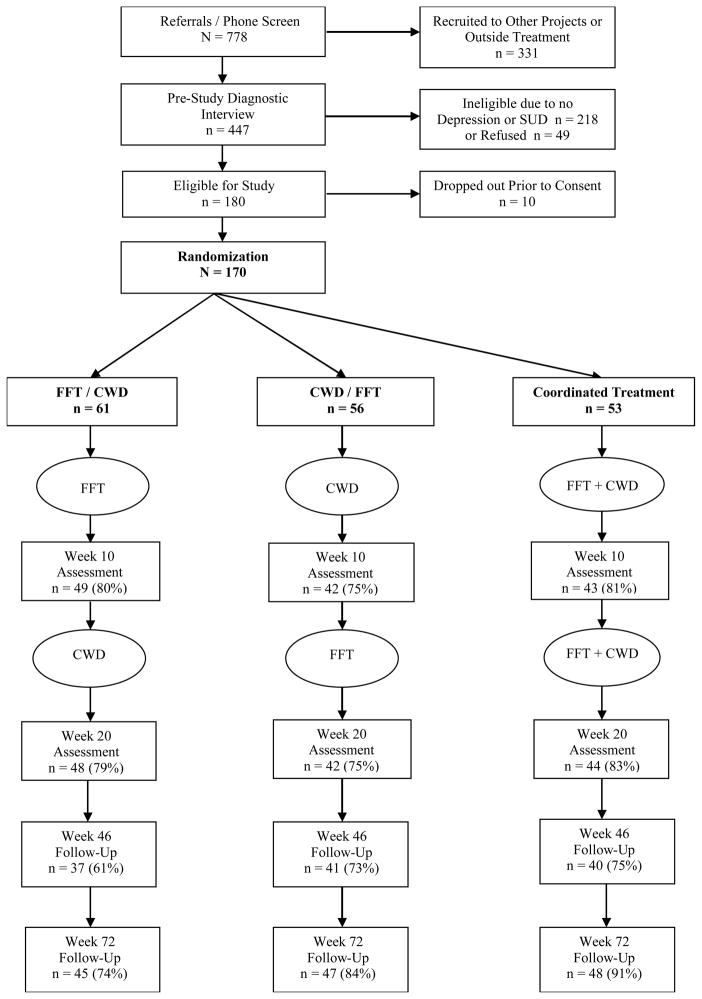

Between 2007–2011, we recruited 170 adolescents from Portland, OR and Albuquerque, NM. Inclusion criteria were: (1) current DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) depressive disorder (major depressive disorder [MDD], dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood; depression not otherwise specified [D-NOS]); (2) current DSM-IV-TR non-nicotine SUD; (3) drug use in the last 90 days, (4) 13–18 years old, and (5) parent willing to participate. Exclusion criteria were: (1) acute suicidal ideation, (2) psychotic symptoms, (3) sibling in the study, and (4) recent change in psychotropic prescription. Most participants (54%) had MDD and cannabis abuse (21%) or dependence (73%); most also met criteria for alcohol abuse (34%) or dependence (31%). The Oregon Research Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study. Adolescents were recruited until a cohort (4–9 families) was formed, which was randomly assigned to one of three sequences: (a) FFT followed by CWD (FFT/CWD), (b) CWD followed by FFT (CWD/FFT), or (c) an intervention combining FFT and CWD (Coordinated Treatment; CT). Therapists were assigned based on availability. Families were interviewed at baseline (Week 0), Week 10 (midtreatment), Week 20 (end of treatment), and Weeks 46 and 72 (6- and 12-month post-treatment, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Through the Study

Assessment of Outcome Measures

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children–Present and Life Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1996). Trained and supervised interviewers assessed adolescents and parents for mood disorders and SUD using the K-SADS-PL. Symptom kappas (random 20% of interviews) were very good: MDD k=.90, SUD k=.87.

Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS; Poznanski & Mokros, 1995) used information from adolescent and parent to create a continuous measure of depression, which served as the primary depression outcome (baseline and follow-up reliability r=.88 and =.92).

Timeline Followback Interview (TLFB; Miller & Del Boca, 1994) is a reliable (e.g., Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005) structured interview with adolescents that reconstructs daily drug use to determine % days of all drug use (either past 90 days or since last assessment, whichever was shorter), which served as the primary substance use outcome variable.1

Treatment Conditions

CWD is a group intervention providing cognitive and behavioral strategies to address adolescent depression. The original intervention was modified from 16 to 12 sessions by removing communication and problem-solving skills (they were included in FFT), shortening sessions from 120 to 90 minutes, and adding a points system to reward participation. FFT is a systems-oriented, behaviorally based model of family therapy (Alexander & Parsons, 1982) that integrates intervention strategies for addictive behaviors to an ecological formulation of family disturbance; standard SUD delivery involves 12 sessions over 10 weeks with 5 treatment phases (engagement, motivation, relational assessment, behavior change, generalization). CT represented a synthesis of FFT and CWD. Overall, family sessions followed FFT. Group treatment consisted of CWD augmented to provide skills aimed at reducing substance use (Waldron & Kaminer, 2004). CT treatment began with 4 family sessions prior to group, which was conducted weekly for 10 weeks with 2 additional sessions in the 20 weeks of treatment.

Ten therapists (1 male) provided both treatments, though youth had a different therapist for FFT versus CWD (unless unavoidable). Therapists had at least a master’s degree in mental health, one year experience with adolescents and families, and were trained in two-day workshops. After FFT training, therapists conducted two pilot cases. Therapists were supervised weekly during treatment. All sessions were videotaped; a random 25% of CWD sessions were rated, as were 2 FFT sessions per family (15%) using established scales, which indicated that therapists adhered to the intervention with no differences across treatment sequences.

Data Analysis Plan

Markov Chain Monte Carlo multiple imputation was used to replace missing data. SPSS19 imputed missing values to create 10 data sets (age and gender conditioned estimates), which did not differ on imputed variable or interactions (all F<1.0). Analyses used the 10 imputed sets but statistics and alpha reflected original sample size. Nesting effects of cohorts and therapists indicated negligible ICCs (e.g., average cohort ICC for CDRS and drug use=.020 and .023). Site effects were nonsignificant. We conducted analyses during either treatment (Weeks 0, 10, 20) or post (Weeks 20, 46, 72) applying a 3 (Sequence) x 2 (MDD) x 3 (Time) factorial repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). We also examined remission (substance use remission=average use <1/week during assessment window; depression remission=CDRS-R< 28).

Results

Baseline characteristics across conditions (Table 1) indicated only one difference for age [F(2, 167)=3.96, p<.02, η2=.046]. The two sites did not differ on MDD rates, age, proportion females, single parents, or family poverty; ethnicity varied by site [χ2(1)=28.99, p<.001], with higher rates of Hispanics in NM (51%) than OR (13%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Condition.

| Variables | Treatment Condition

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| FFT/CWD (n = 61) | CWD/FFT (n = 56) | CT (n = 53) | |

| % days alcohol use1 | 8.55 (13.74) | 10.97 (17.44) | 13.22 (21.33) |

| % days tobacco1 | 51.57 (43.94) | 61.17 (40.31) | 57.04 (40.01) |

| % days marijuana use1 | 47.54 (35.10) | 62.31 (34.10) | 50.97 (34.13) |

| % marijuana dependence | 67.21% | 67.86% | 62.26% |

| % days any substance use1,2 | 54.61 (33.18) | 64.60 (32.25) | 58.95 (29.40) |

| CDRS (T>60) | 84% | 86% | 68% |

| MDD | 57.4% | 58.9% | 43.4% |

| Age in years* | 16.24 (1.40) | 16.10 (1.40) | 16.83 (1.13) |

| Age of first drug use | 11.3 (2.2) | 12.7 (2.3) | 12.4 (2.2) |

| Gender (% female) | 24.6% | 23.2% | 18.9% |

| Hispanic Ethnicity (%) | 29.5% | 23.2%% | 32.1% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 60.7% | 62.5% | 58.5% |

| Parent education: Some College | 73.7% | 76.8% | 83% |

| Below 200% of Poverty level | 30.5% | 39.3% | 43.4% |

| Single Parent | 44.3% | 51.8% | 39.6% |

FFT = Functional Family Therapy; CWD = Coping With Depression; CT = Coordinated Treatment (FFT +CWD). MDD = major depressive disorder.

p < 0.05.

Past 90 days;

Any substance excluding tobacco.

Premature termination (i.e., attending<2 sessions) rates were FFT/CWD=11%; CWD/FFT=16%; CT=8% (differences ns; Total=12%). CWD attendance was lower (p<.05) in FFT/CWD (M=6.0, SD=4.1) than either CWD/FFT (M=7.8, SD=2.9) or CT (M=7.4, SD=3.8). Similarly, FFT attendance was lower (p<.001) in CWD/FFT (M=6.8, SD=5.2) than FFT/CWD (M=10.5, SD=3.0) or CT (M=10.8, SD=3.8). Sequence had an effect for total attendance [F(2, 164)=3.68, p<.03, η2=.043]; CWD/FFT had less attendance (M=12.7, SD=8.5) than CT (M=16.8, SD=8.1) [t(107)=2.67, p<.03] but neither differed from FFT/CWD (M=15.4, SD=8.1).

Substance Use Outcome

Change during treatment

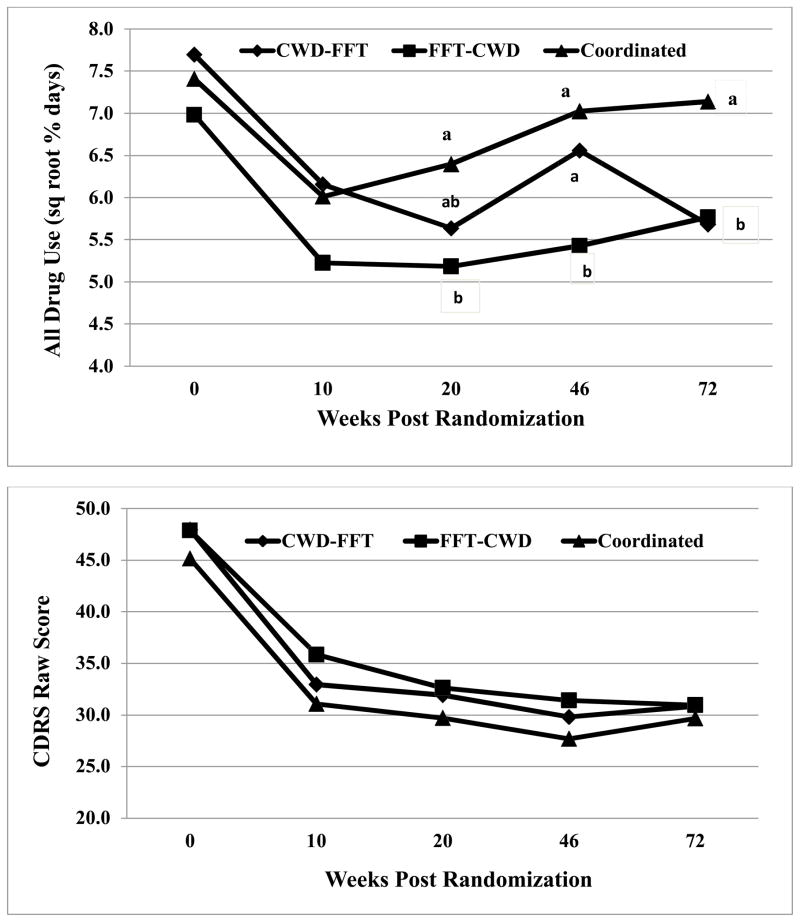

Outcome rates are reported in Table 2. Regarding change during treatment (square root transformation controlled for kurtosis), repeated measures ANOVA found significant effects for Sequence [F(2,160)=3.51, p<.03, η2=0.04], Time [F(2,320) 11.72, p<.0001, η2=0.07], and Sequence X MDD [F(2,320)=3.45, p<.03, η2=0.04]. Gender or age did not modify these (or any subsequent) results. We compared treatments at Week 10 and 20 covarying baseline drug use (Figure 2). Treatments did not differ at Week 10, but FFT/CWD (M=5.10, SD=3.31) had lower substance use [t(120)=2.50, p<.02] than CT (M=6.40, SD=2.99) at Week 20; neither differed from CWD/FFT (M=5.80, SD=3.09). To evaluate the Sequence X MDD interaction, we computed pairwise comparisons (Table 2). For non-MDD participants, all sequences were associated with reductions (p<.05), though change was greater for FFT/CWD (d=1.41) compared to CWD/FFT (d=0.56) or CT (d=0.48), which did not differ. For MDD participants, the two sequenced delivery conditions were associated with substance use reductions, but CWD/FFT resulted in reduced use (d=1.19) that was significantly greater (p<.05) than FFT/CWD (d=0.43) or CT (d=0.36), which did not differ.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations for the all drug use measure (TLFB square root % days) by Treatment Condition, Depression Diagnosis, and Assessment Point.

| Treatment Condition | MDD Present | During Treatment | Post Treatment | In Treatment F |

Post Treatment F |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline | Week 10 | Week 20 | Week 46 | Week 72 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| FFT/CWD | No | 6.81 (2.27)a | 4.54 (2.98)b | 3.99 (3.11) bA | 4.68 (2.56) A | 4.95 (3.22) A | 28.31 *** | 1.25 |

| CWD/FFT | No | 7.78 (2.34)a | 6.51 (3.57)b | 6.24 (3.20)bA | 6.24 (3.19) A | 5.85 (3.93) A | 4.16 * | 0.18 |

| CT | No | 7.47 (2.24)a | 5.51 (2.99)b | 6.22 (3.12) bA | 6.82 (2.92)A | 7.13 (2.91) A | 7.38*** | 1.96 |

| Combined | No | 7.34 (2.31)a | 5.47 (3.25)b | 5.48 (3.31)bA | 6.44 (3.23)A | 6.04 (3.45)A | 28.63*** | 1.36 |

| FFT/CWD | Yes | 7.11 (2.73)a | 5.70 (3.22)b | 6.07 (3.24)abA | 6.18 (3.27)A | 6.44 (3.42)AB | 3.82 * | 0.38 |

| CWD/FFT | Yes | 7.64 (2.22)a | 5.90 (3.25)b | 5.26 (3.06)bA | 6.72 (2.64)B | 5.59 (3.47)A | 8.26*** | 3.69* |

| CT | Yes | 7.33 (2.01)a | 6.67 (3.11)a | 6.65 (2.70)aA | 7.32 (2.89)A | 7.15 (3.15)A | 1.57 | 0.92 |

| Combined | Yes | 7.39 (2.28)a | 6.02 (3.22)b | 5.91 (3.09)bA | 6.66 (2.99)B | 6.30 (3.42)AB | 11.64*** | 3.20* |

Note: Cell Entries are means and standard deviations (SD) for Treatment x Diagnosis combinations. Subscripts represent pairwise comparisons among conditions based upon Bonferroni criteria (α/3) to adjust for the multiple comparisons within contrasts; cells sharing a subscript do not differ. Comparisons are to be made only within a single row and among lower case (contrast during treatment) or upper case (contrast post treatment) subscripts.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Means of Treatment Conditions on All Drug Use (Square Root) and Child Depression Rating Scale (raw scores) Across Time.

Note: Cells sharing a subscript in common are not significantly different by pairwise t-test. Comparisons are to be made only within a single time point.

Change following treatment

Results of the second piecewise [3 (Sequence) x 2 (MDD) x 3 (Time: Week 20, 46, 72)] repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect for Sequence [F(2,320)=4.77, p<.010, η2=0.06]. To evaluate, we compared sequences at Weeks 46 and 72 (Figure 2). Week 46 results indicated that FFT/CWD (M=5.37, SD=3.07) had lower substance use compared to both CWD/FFT [M=6.65, SD=2.78, t(120)=2.42, p<.017] and CT [M=6.97, SD=2.95], t(120)=3.17, p<.001), which did not differ. At Week 72, CT (M=7.06, SD=3.06) had higher substance use than both FFT/CWD [M=5.74, SD=3.40 t(120)=2.06, p<.04) and CWD/FFT [M=5.74, SD=3.40 t(120)=1.98, p<.055), which did not differ.

Depression Severity Outcome

Change during treatment

Rates for the second outcome are reported in Table 3. Regarding acute treatment change, results showed main effects for MDD [F(1, 160)=50.81, p<.0001, η2=0.24], Time [F(2, 320)=120.87, p<.0001, η2=0.43], and MDD x Time [F(2, 320)=21.37, p<.0001, η2=0.12] (Figure 2). None of the effects involving Sequence were significant [Sequence x Time, F< 1.00, η2 = 0.005; Sequence x MDD x Time, F(4,320) = 1.90, p < .11. η2 = 0.02]. To evaluate the Time x MDD interaction, we performed multiple comparisons (Bonferroni adjusted). For MDD participants, baseline CDRS (M =37.90. SD=8.12) was higher (p<.01) than Weeks 10 (M =30.17, SD=10.13) and 20 (M=29.19, SD=10.16) (which did not differ). For non-MDD participants, baseline CDRS (M=54.80, SD=11.47) was higher (p<.01) than Weeks 10 (M=36.11, SD=12.67) and 20 (M=33.38, SD=12.73) (which also did not differ). Differences between youth with or without MDD were significant at Weeks 10 [t(168)=3.25, p<.001, d=0.50] and 20 [t(168)=2.15, p<.001, d=0.36]. In sum, all three sequences were associated with depression reductions for both MDD and non-MDD participants.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for the Child Depression Rating Scale (raw scores) by Treatment Condition, Depression Diagnosis, and Assessment Point.

| Treatment Condition | MDD Present | During Treatment | Post Treatment | During F |

Post F |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline | Week 10 | Week 20 | Week 46 | Week 72 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| FFT/CWD | No | 38.65 (7.63)a | 33.65 (13.36)ab | 29.66 (11.93)bA | 27.98 (12.94)A | 28.88 (12.71)A | 6.89** | 0.26 |

| CWD/FFT | No | 40.05 (7.67)a | 29.46 (5.16)b | 28.36 (6.74)bA | 26.26 (6.72)A | 26.56 (8.44)A | 21.68*** | 0.75 |

| CT | No | 35.67 (8.34)a | 27.66 (8.73)b | 29.37 (10.57)bA | 26.10 (8.54)AB | 24.47 (8.23)B | 9.42*** | 3.76* |

| Combined | No | 37.90 (8.12)a | 30.17 (10.13)b | 29.19 (10.16)bA | 26.77 (9.85)B | 26.53 (10.16)B | 30.96*** | 3.00* |

|

|

||||||||

| FFT/CWD | Yes | 54.71 (11.04)a | 37.31 (14.38)b | 34.78 (12.57)bA | 33.84 (12.82)A | 32.57 (14.94)A | 37.34*** | 0.54 |

| CWD/FFT | Yes | 53.06 (11.65)a | 35.24 (11.60)b | 34.21 (13.40)bA | 32.38 (11.35)A | 33.50 (16.06)A | 32.66*** | 0.68 |

| CT | Yes | 57.52 (11.39)a | 35.56 (11.23)b | 30.03 (11.32)bA | 29.65 (12.85)A | 36.41 (20.02)B | 44.01*** | 2.23 |

| Combined | Yes | 54.80 (11.47)a | 36.11 (12.67)b | 33.38 (12.73)bA | 32.25 (12.40)A | 33.87 (16.80)A | 113.92*** | 1.36 |

Note: Cell Entries are means and standard deviations (SD) for Treatment x Diagnosis combinations. Subscripts represent pairwise comparisons among conditions based upon Bonferroni criteria (α/3) to adjust for the multiple comparisons within contrasts; cells sharing a subscript do not differ. Comparisons are to be made only within a single row and among lower case (during treatment) or upper case (post treatment) subscripts.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Change following treatment

Results for the second part of the piecewise model indicated that MDD adolescents (M=33.87, SD=16.80) had a higher [F(1, 164)=13.01, p<.001, η2=0.07] mean CDRS score during follow-up than non-MDD participants (M=26.52, SD=10.16).

Indices of Substance Use and Depression Remission

Substance use remission was achieved by 33% by Week 20, with higher rates for FFT/CWD (44%) than CT [23%, χ2(1)=5.10, p<.02]; rates for CWD/FFT (31%) were intermediate. At Week 72, substance use remission rates for FFT/CWD [32%, χ2(1)=3.79, p<.05] and CWD/FFT [33%, χ2(1)=3.77, p<.05] were both higher than CT [17%]. Regarding depression remission, 47% remitted by Week 20, with no difference for sequences [FFT/CWD=44%, CWD/FFT=45%, CT=52%; χ2(2)=1.75, p<.42). By end of follow-up, 60% achieved depression remission with no difference for sequences [FFT/CWD=60%, CWD/FFT=54%, CT=65%; χ2(2)=1.46, p<.48].

Impact of Adjunctive Outpatient Treatment and Prescription Medication Usage

We examined non-protocol treatment and medication usage, creating four variables that represented adjunctive therapy or prescription (depression/anxiety) usage during acute treatment or follow-up. Treatment sequences differed in the proportion of youth who reported adjunctive treatment during acute treatment (FFT/CWD=16%; CWD/FFT=49%; CT=20%) [χ2(2)=16.34, p<.001]; differences between sequences during follow-up did not differ (FFT/CWD=34%; CWD/FFT=31%; CT=32%). Sequence differences in medication usage did not differ during either acute treatment (FFT/CWD=31%; CWD/FFT=36%; CT=28%) or follow-up (FFT/CWD=22%; CWD/FFT=32%; CT=28%). We conducted four factorial repeated measures ANOVAs with Sequence and Time (acute or post-treatment) as independent variables and the four indices of non-study treatment as moderators. Medication did not interact with Time or Time x Sequence either during or post treatment. Adjunctive therapy did not interact with Time or Time x Sequence during treatment but moderated time in the follow-up [F(2, 258)=9.98, p<.001, η2= 0.072]; average change (d) for participants who received non-study treatment during follow-up was 0.47 [t(89) =2.22, p<.03], reflecting substance use reductions from Weeks 20 to 72, whereas those who did not receive adjunctive therapy during follow-up had a negative effect [t(43) =4.30, p<.01, d=-0.53], which reflected a substance relapse post-treatment.

Parallel analyses were conducted with depression. Medication usage did not moderate change either during or post treatment. Adjunctive therapy did not interact with time in the acute phase but was significant post-treatment [F(2, 258)=5.09, p<.007, η2= 0.028]; average change (d) for participants who received adjunctive therapy during follow-up was 0.45 [t(87) =3.32, p<.002], reflecting continued depression reductions from Weeks 20 to 72, whereas participants who did not receive adjunctive therapy during follow-up did not improve [t(42)=0.61, p<.68, d=-0.08].2

Discussion

This study examined the effects of three treatment sequences, two serial and the third coordinated, on reducing substance use and depression in adolescents who entered treatment with these comorbid conditions. Regarding substance use, we found main effects for treatment sequence and time that were medium in magnitude. In addition, MDD had a small but significant moderating effect on treatment sequence. After treatment ended, treatment sequence had a medium effect. Overall, data suggest that FFT/CWD was the most effective treatment in reducing substance abuse, achieving lower substance use rates compared to coordinated treatment through follow-up. Consistent with the notion that multiple treatment efforts are needed to achieve remission, a surprisingly large proportion of adolescents received non-study treatment, especially those in CWD/FFT. Non-study treatment did not moderate acute effects for substance use, but those who received additional outpatient therapy during follow-up experienced continued substance use reductions, whereas those who received no additional treatment experienced a significant negative substance use effect, indicative of relapse.

MDD moderated the impact of treatments on substance use. If MDD was present, providing depression-focused CBT treatment first followed by FFT resulted in greater substance use reductions during treatment and follow-up. Conversely, if MDD was not present, the three treatment sequences had a similar pattern of substance use results. Previous research has found that CBT for depression has improved SUD outcomes for depressed adults in addiction treatment when provided in combination with substance-focused treatment (e.g., Brown et al., 1997).

Depressive symptoms showed a markedly different pattern. Depression reductions occurred early in treatment across all three sequences. Most relevant to clinical recommendations, no treatment sequence resulted in more rapid depression recovery. Approximately 40% achieved depression remission during treatment and that rate rose to 60% one year post-treatment, which is consistent with the episodic nature of depressive disorders. Analyses examining the impact of non-study treatment found no effect of medication utilization on depression outcomes, either during or following treatment. However, as seen for substance use, participants who received non-protocol therapy during follow-up experienced continued depression reductions.

In addition to changes in substance use and depression outcomes, we examined the degree to which adolescents in the three treatment sequences attended both family and group-based treatments. Substance abusing adolescents are notoriously difficult to engage and retain in therapy, and approximately 1 in 10 participants failed to engage in treatment across conditions. For youths in either sequenced condition, there was significantly lower engagement for the second modality, especially when it was family-based treatment. One interpretation is that families in both sequenced conditions experienced a fair degree of symptom relief in the first 10 weeks of treatment and may have felt less motivated to engage in the second treatment. A second potential explanation is that introducing a new therapist midway through treatment led to dropout. Regardless of the explanation, there may be a fairly narrow window of opportunity for engaging adolescents in multi-focused treatment, and engaging families appears especially difficult if that family-based modality is not introduced early in care.

No evidence suggested that coordinated treatment was superior to either sequenced condition for either outcome. One potential explanation is that coordinated care failed to create a clear and consistent model of change. Also, adolescents in CT interacted with different CWD and FFT therapists simultaneously, which may have impacted the alliance with each provider. Lastly, the CT condition was developed for this study and may not have been optimal.

Study limitations should be acknowledged. First, treatment occurred in a center providing SUD treatment and participants may not have wanted or thought they needed depression treatment. Second, the majority of participants were male, which is not common in depression treatment research but is the norm in studies of adolescent SUD. Third, other psychiatric conditions were not assessed. Fourth, the CWD intervention was modified for use with this population. Fifth, the study design did not include a usual care condition or wait-list control. It is not known whether any of the treatment approaches would be more effective than routine care or the passage of time. On a related note, we were unable to restrict families from seeking additional treatment and the uncontrolled inclusion of non-protocol interventions seriously limited our ability to interpret the study findings with a high level of confidence.

The goal of this study was to inform understanding regarding the most effective methods of intervening with the common and challenging population of depressed substance-abusing adolescents, but the results also suggest future research directions. First, the strikingly similar degree to which reductions in depression occurred across all three treatment sequences suggests that research identify what factors mediate depression changes in different treatment modalities. Second, moderational analyses, including more sophisticated classification tree and Bayesian additive regression tree models, have the potential of optimizing treatment selection for individual clients. Third, given the strong potential for attrition, future research should attempt to identify the most potent active treatment elements necessary for reducing both depression and substance use as quickly as possible, whether treatments are provided in a sequenced, coordinated or truly integrated fashion.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant DA21357 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We wish to thank our project staff and the participants who made this study possible.

Footnotes

Urine drug screens were obtained using standard procedures at each assessment using a 10-panel screen plus alcohol. Positive urine screens for cannabinoids occurred at baseline (62%), Week 10 (63%), Week 20 (64%), Week 46 (77%), and Week 72 (72%). The dichotomous urine screen result and 90 day self-reported use results were significantly (all tests p<.001) correlated with percent days marijuana use at each assessment. Baseline dichotomous urine screen results also significantly correlated with self-reported opiate use (r=.24; p<.001) but not with other self-reported use. We assessed one possible attrition bias on urine screen results by evaluating whether adolescents were less likely to complete assessments based upon their initial urine screen results. The percent of adolescents at each assessment with positive urine screens at baseline did not differ across time points (baseline=61%, Week 10=63%; Week 20=62%; Week 46=61%; Week 72=60%). A positive urine screen for marijuana was not significantly associated with attendance in post-baseline assessments or with either FFT or CWD attendance (number of sessions; all p>.19).

The percentage of individuals in drug use remission at Week 72 was significantly higher for individuals receiving adjunctive therapy during follow-up than for those who did not receive additional treatment (42% vs. 20%, respectively; corrected χ2(1)=10.33, p<.001). The receipt of adjunctive therapy during follow-up was not significantly associated with depression remission at Week 72 (62% vs.63%; corrected χ2(1)=0.00, p<1.00).

References

- Alexander JF, Parsons BV. Functional family therapy: Principles and procedures. Carmel, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong T, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Evans M, Miller IW, Burgess ES, Mueller TI. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:715–726. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. Adolescent Coping With Depression Course. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Douaihy A, Bukstein OG, Daley DC, Wood SC, Kelly TM, Salloum IM. Evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy/motivational enhancement therapy (CBT/MET) in a treatment trial of comorbid MDD/AUD adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik JS. Concordance between biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:404–413. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Dennis ML, Godley MD, Funk RR. Thirty-month relapse trajectory cluster groups among adolescents discharged from out-patient treatment. Addiction. 2004;99:s2, 129–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. Diagnostic Interview - Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) Pittsburgh, PA: Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Tomlinson KL, Anderson KG, Marlatt GA, Brown SA. Relapse in alcohol- and drug-disordered adolescents with comorbid psychopathology: Changes in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:28–35. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski E, Mokros H. Children’s Depression Rating Scale – Revised (CDRS-R) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs PD, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Davies RD, Lohman M, Klein C, Stover SK. Randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents with major depression, behavior problems, and substance use disorders. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:1026–1034. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Kaufman NK. Impact of comorbidity on a cognitive-behavioral group treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:795–802. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Kaminer Y. On the learning curve: The emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction. 2004;99:93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Turner CW. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:238–261. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Turner CW, Ozechowski TJ. Profiles of change in behavioral and family interventions for adolescent substance abuse and dependence. In: Liddle HA, Rowe CL, editors. Adolescent substance abuse: Research and clinical advances. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Warden D, Riggs PD, Min SJ, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Tamm L, Trello-Rishel K, Winhusen T. Major depression and treatment response in adolescents with ADHD and substance use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;120:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]