Abstract

Background. Few studies have prospectively assessed viral etiologies of acute respiratory infections in community-based elderly individuals. We assessed viral respiratory pathogens in individuals ≥65 years with influenza-like illness (ILI).

Methods. Multiplex reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction identified viral pathogens in nasal/throat swabs from 556 episodes of moderate-to-severe ILI, defined as ILI with pneumonia, hospitalization, or maximum daily influenza symptom severity score (ISS) >2. Cases were selected from a randomized trial of an adjuvanted vs nonadjuvanted influenza vaccine conducted in elderly adults from 15 countries.

Results. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was detected in 7.4% (41/556) moderate-to-severe ILI episodes in elderly adults. Most (39/41) were single infections. There was a significant association between country and RSV detection (P = .004). RSV prevalence was 7.1% (2/28) in ILI with pneumonia, 12.5% (8/64) in ILI with hospitalization, and 6.7% (32/480) in ILI with maximum ISS > 2. Any virus was detected in 320/556 (57.6%) ILI episodes: influenza A (104/556, 18.7%), rhinovirus/enterovirus (82/556, 14.7%), coronavirus and human metapneumovirus (each 32/556, 5.6%).

Conclusions. This first global study providing data on RSV disease in ≥65 year-olds confirms that RSV is an important respiratory pathogen in the elderly. Preventative measures such as vaccination could decrease severe respiratory illnesses and complications in the elderly.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, elderly, respiratory infection, influenza, epidemiology, prevalence, polymerase chain reaction

Elderly individuals are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to microbial infections because of coexisting chronic disease and immune senescence [1]. The contribution of noninfluenza viral infections to acute respiratory illness in the elderly has not been well studied, partly due to difficulties in diagnosis due to atypical presentations and low viral loads [2–5]. However, identification of respiratory viruses is now possible with the advent of sensitive molecular detection methods, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [6, 7].

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is increasingly recognized as an important cause of respiratory infections in adults, particularly affecting the elderly, immunocompromised, and those with underlying chronic cardiopulmonary disease [8]. RSV appears to be a predictable cause of wintertime respiratory illnesses among older adults living in congregate settings such as long-term care or attending daycare and is estimated to infect 5%–10% of nursing home residents per year, with rates of pneumonia and death of 10%–20% and 2%–5%, respectively [9].

Few studies have prospectively assessed etiologies of acute respiratory infections in community-based elderly individuals [8, 10]. Much of the available data describing RSV and other viral infections in the elderly come from a limited number of geographic locations, primarily the United States (US). Different cultures, climates, and intergenerational household members might influence infection rates; thus, global data on RSV and other respiratory viral infections in this population are needed. We used multiplex reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to identify viral respiratory pathogens in nasal and throat swabs from episodes of moderate-to-severe influenza-like illness (ILI) in influenza-vaccinated elderly individuals.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This laboratory-based, epidemiological study assessed the prevalence of RSV and other respiratory viruses in samples collected during the first surveillance year of the INFLUENCE65 clinical trial [11]. INFLUENCE65 (www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00753272) was a Phase III randomized, controlled study evaluating the relative efficacy of the AS03-adjuvanted trivalent split-virion influenza vaccine compared to unadjuvanted vaccine during the 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 influenza seasons, in 43 802 adults aged 65 years and older. The study was conducted in 3 continents in the northern hemisphere: America (Canada, Mexico, and the US), Europe (Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Norway, Poland, Romania (see Table 2 footnote), Russia, the Netherlands, UK), and East Asia (Taiwan). Study participants were community-based or living in retirement homes, which allowed mixing in the community. Bedridden elderly individuals were not eligible.

Table 2.

Distribution of Single Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)/RSV-mixed Infections and RSV Subtypes by Disease Status

| Number of Subjects (N) | Total (N = 556) |

Pneumonia (N = 28) |

Hospitalized (N = 64) |

ISS score >2 (N = 490)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | nb | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) |

| RSV alone | 39 | 7.0 (5.0–9.5) | 2 | 7.1 (.9–23.5) | 7 | 10.9 (4.5–21.2) | 34 | 6.9 (4.9–9.6) |

| RSV and another virus detected | 2 | 0.4 (.0–1.3) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 1 | 1.6 (.0–8.4) | 1 | 0.2 (.0–1.1) |

| Any RSV | 41 | 7.4 (5.3–9.9) | 2 | 7.1 (.9–23.5) | 8 | 12.5 (5.6–23.2) | 35 | 7.1 (5.0–9.8) |

| Any RSV subtype A | 14 | 2.5 (1.4–4.2) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 2 | 3.1 (.4–10.8) | 12 | 2.4 (1.3–4.2) |

| Any RSV subtype B | 27 | 4.9 (3.2–7.0) | 2 | 7.1 (.9–23.5) | 6 | 9.4 (3.5–19.3) | 23 | 4.7 (3.0–7.0) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval;ISS, influenza symptom severity score; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a Includes 10 subjects who had an ISS score >2 and were also hospitalized or had pneumonia.

b n, no. of subjects in a given category.

Informed consent was given to participate in INFLUENCE65. Samples from US subjects were not included in the present study as ethics approval for additional virologic studies would have been required, leaving a study population of 36 132 subjects.

Surveillance and Case Definition

Active surveillance undertaken between the 15th of November and 30th of April comprised weekly or biweekly telephone contacts or home visits. Participants were instructed to report any ILI. Nose and throat swabs were collected from subjects who developed an ILI during the surveillance period.

An ILI was defined as the simultaneous occurrence of at least 1 respiratory symptom (nasal congestion, sore throat, new/worsening cough, dyspnea, sputum production, or wheezing) and one systemic symptom (headache, fatigue, myalgia, feverishness [feeling hot or cold, having chills or rigors], fever [oral temperature of ≥37.5°C]). Because moderate-to-severe ILIs have the most clinically significant implications in terms of complications and associated healthcare costs, we evaluated the etiology of ILI episodes meeting predefined severity criteria. Thus, for the present study, only samples from episodes of moderate-to-severe ILI were selected: defined as associated with pneumonia (based on signs and symptoms with a chest radiograph demonstrating a new or progressive infiltrate), or with hospitalization, or with a maximum (ie, the highest total score achieved on days 0–14) daily Influenza Symptom Severity (ISS) score >2.

Influenza Symptom Severity Questionnaire

The ISS questionnaire assesses the severity of 10 symptoms including 3 respiratory (cough, sore throat, and nasal congestion) and seven systemic (headache, feeling feverish, body aches, fatigue, neck pain, interrupted sleep, and loss of appetite) symptoms using a 3-point grading system (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) and has been validated for influenza infection [12]. The 10 individual scores (systemic and respiratory) were averaged daily with a final score ranging from 0 to 3. The questionnaire was completed for 15 days.

Sample Collection

Nasal and throat swabs were collected by a study nurse or physician using standardized methods, within 5 days after the onset of each ILI episode, then stored at −70°C. Nucleic acids were extracted from each sample and stored below −60°C at GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines' laboratory [13].

Sample Selection

There were 4582 samples collected from 5389 ILI episodes during the INFLUENCE65 2008–2009 surveillance period. We tested 556 (12%) of these samples from subjects who fulfilled the criteria for a moderate-to-severe ILI. One sample per episode was included, but subjects could be included more than once if they had more than 1 ILI episode meeting severity criteria and if there were at least 7 symptom-free days between episodes.

Respiratory Virus Identification

The xTAG® Respiratory Viral Panel (US IVD 96 tests; Luminex, Abbott Molecular, Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium) is a qualitative multiplex RT-PCR used to simultaneously detect and identify nucleic acids from different pathogens. The following respiratory viruses and virus subtype genomes were amplified: Influenza A and subtypes H1, H3, and H5, Influenza B, RSV subtypes A and B, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3, and 4, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus/enterovirus (the test does not differentiate between the 2), adenovirus, coronaviruses 229E, OC43, NL63, HKU1, and SARS as described elsewhere [14, 15]. The analytical sensitivity ranged from 0.1 to 1 TCID50, corresponding to approximately 50 to 250 genome equivalents [14].

Statistical Methods

The primary objective was to estimate the prevalence of RSV in nasal/throat swabs in community-based elderly individuals with moderate-to-severe ILI. Secondary objectives were to estimate the prevalence of other respiratory viruses in this population, and in subgroups defined by pneumonia occurrence, hospitalization status, and ISS score >2. Statistical analyses used SAS Version 9.1 or later. Prevalence was calculated as a proportion with its 2-sided exact 95% confidence interval (CI) [16]. Possible associations between prevalence and baseline characteristics/clinical symptoms were explored using logistic regression with significance level set at P < .05.

Role of the Funding Source

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA designed the study, collected and analyzed data, interpreted the results, and wrote the report. All authors had access to the data and had final responsibility for the analysis, interpretation, and decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

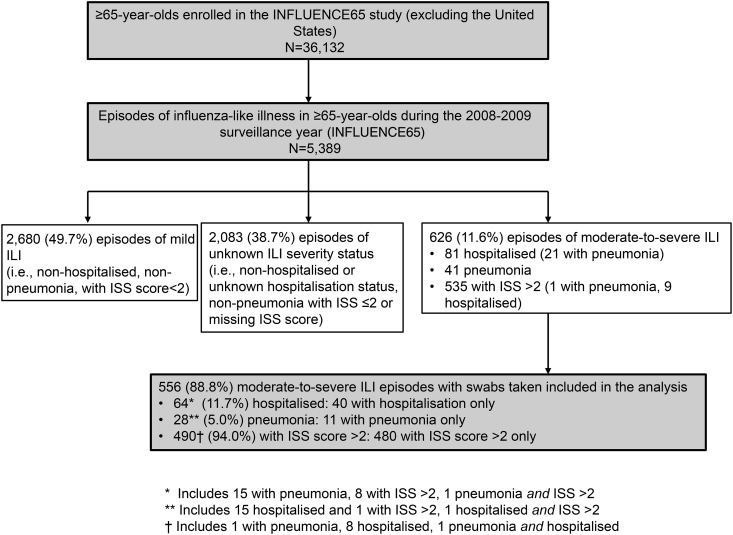

Nasal/throat swabs were collected for 88.8% (556/626) moderate-to-severe ILI episodes reported during the first surveillance year of the INFLUENCE65 study (Figure 1). ILI episodes and swab collection peaked in January 2009 (Supplementary Figure 1). The ISS questionnaire was completed by approximately 70% of subjects reporting any ILI episode (81%, 47/58 of moderate-to-severe ILI episodes with missing ISS scores were hospitalized).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

We tested samples from 553 subjects with 556 episodes of moderate-to-severe ILI: 64 (11.7%) were hospitalized episodes and 28 (5.0%) were pneumonia cases. Of 490 (94.0%) episodes with a maximum ISS score >2, 480 (86.3%) were nonhospitalized, nonpneumonia cases, including 9 with unknown hospitalization status (Figure 1). No deaths occurred in association with the 556 moderate-to-severe ILI episodes included in the analysis.

The study population was representative of the INFLUENCE65 cohort [11]. There were more women than men, and the mean age of subjects was 72.8 years (standard deviation 5.5 years, Table 1). Most subjects were white (88.6%), most lived independently (91.7%), 6.0% were in active employment, and 9.6% were current smokers. The most common preexisting medical conditions were hypertension (65.7% of subjects), other cardiopulmonary diseases (52.5%), noninflammatory cerebrovascular/neurological disorders (30.9%), coronary artery disease (28.6%), and autoimmune/inflammatory disease (24.2%).

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic Characteristics by Subject (Total Cohort: N = 553 Subjects With Moderate-to-Severe Influenza-like Illness With Samples Collected)

| Characteristic | Category | All Subjects | Subjects Hospitalizeda | Subjects With Pneumoniaa | Subjects With ISS Score >2a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects (N) | N = 553 | N = 62 | N = 28 | N = 490 | |

| Age, years | Mean (SD) | 72.8 (5.5) | 74.3 (5.8) | 71.9 (5.4) | 72.7 (5.5) |

| Range | 65.0–93.0 | 65.0–88.0 | 65.0–87.0 | 65.0–93.0 | |

| Age group, n (%)b | 65–69 | 178 (32.2) | 14 (22.6) | 11 (39.3) | 160 (32.7) |

| 70–74 | 181 (32.7) | 21 (33.9) | 9 (32.1) | 163 (33.3) | |

| 75–79 | 124 (22.4) | 15 (24.2) | 5 (17.9) | 109 (22.2) | |

| 80+ | 70 (12.7) | 12 (19.4) | 3 (10.7) | 58 (11.8) | |

| Gender ratio | Women/Men | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Life independence status, n (%)c | Independent | 507 (91.7) | 52 (83.9) | 27 (96.4) | 453 (92.4) |

| Low-level care | 18 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (3.7) | |

| High level care | 28 (5.1) | 10 (16.1) | 1 (3.6) | 19 (3.9) |

Abbreviations: ISS, influenza symptom severity score; SD, standard deviation.

a One subject may belong to >1 category.

b n (%), no. (percentage) of subjects in a given category.

c Low-level care: care with living arrangement provisions that cater for having chronic limitations. High-level care: provides more intense supervision, intermittent services, and nursing care for those who require high support

Prevalence of RSV in Nasal and Throat Samples

RSV was detected in 41/556 (7.4%) moderate-to-severe ILI episodes (95% CI, 5.3%–9.9%). Most were single infections (39/41). The prevalence of RSV detection was 7.1% (2/28) in episodes with pneumonia, 12.5% (8/64) in episodes with hospitalization, and 6.7% (32/480) in episodes with a maximum ISS score >2 (Table 2). The median length of hospitalization for RSV was 6 days (range, 3–20 days) vs median 10 days (range 2–46) for hospitalized cases without RSV (ie, 24/64 cases with another virus detected and 32/64 with no virus detected).

RSV was detected in 11/179 (6.1%) episodes in subjects 65–69 years of age (95% CI, 3.1–10.7), 13/182 (7.1%) episodes in 70–74 years olds (95% CI, 3.9–11.9), 11/124 (8.9%) episodes in 75–79 year olds (95% CI, 4.5–15.3), and in 6/71 (8.5%) episodes in ≥80 year olds (95% CI, 3.2–17.5). Subjects with and without RSV were of similar age and gender distribution, had a similar proportion of pneumonia episodes, and mean ISS score (data not shown). Hospitalization occurred in 19.5% (8/41) of RSV positive episodes and in 10.9% (56/515) of RSV negative episodes (56/506 [11.1%] excluding 9 with unknown hospitalization status). There was no significant association between hospitalization status and RSV detection (Fishers exact P = .12).

No RSV was detected among 98 moderate-to-severe ILI cases in the Russian Federation, or in several of the countries with fewer than 20 moderate-to-severe ILI cases: Estonia (N = 17), Taiwan (N = 4), and the United Kingdom (N = 13; Table 3). RSV prevalence in individual countries ranged from 2.0% (1/50) in Mexico, to 17.1% (12/70) in Czech Republic. The highest prevalence was observed in the Czech Republic (17.1%, 12/70), Norway (15.4%, 2/15), and Germany (14.9%, 7/47). There was a significant association between country and RSV detection (P = .004). Both RSV subtypes (A and B) were detected, although the numbers of each subtype in each country were too small to identify trends (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and Percentage of Moderate-to-Severe Influenza-like Illness (ILI) Episodes Positive for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV: Any and by Subtype) or Any Virus by Country

| Country | Total Samples |

RSV Episodes |

RSV Subtype A |

RSV Subtype B |

Any Virus Detected |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | % of Total | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | |

| Belgium | 20 | 3.6 | 1 | 5.0 (.1–24.9) | 1 | 5.0 (.1–24.9) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–16.8) | 14 | 70.0 (45.7–88.1) |

| Canada | 38 | 6.8 | 2 | 5.3 (.6–17.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–9.3) | 2 | 5.3 (.6–17.7) | 18 | 47.4 (31.0–64.2) |

| Czech Rep. | 70 | 12.6 | 12 | 17.1 (9.2–28.0) | 2 | 2.9 (.3–9.9) | 10 | 14.3 (7.1–24.7) | 53 | 75.7 (64.0–85.2) |

| Estonia | 17 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–19.5) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–19.5) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–19.5) | 8 | 47.1 (23.0–72.2) |

| France | 30 | 5.4 | 1 | 3.3 (.1–17.2) | 1 | 3.3 (.1–17.2) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–11.6) | 17 | 56.7 (37.4–74.5) |

| Germany | 47 | 8.5 | 7 | 14.9 (6.2–28.3) | 3 | 6.4 (1.3–17.5) | 4 | 8.5 (2.4–20.4) | 26 | 55.3 (40.1–69.8) |

| Mexico | 50 | 9.0 | 1 | 2.0 (.1–10.6) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–7.1) | 1 | 2.0 (.1–10.6) | 31 | 62.0 (47.2–75.3) |

| Netherlands | 45 | 8.1 | 3 | 6.7 (1.4–18.3) | 2 | 4.4 (.5–15.1) | 1 | 2.2 (.1–11.8) | 33 | 73.3 (58.1–85.4) |

| Norway | 13 | 2.3 | 2 | 15.4 (1.9–45.4) | 1 | 7.7 (.2–36.0) | 1 | 7.7 (.2–36.0) | 8 | 61.5 (31.6–86.1) |

| Poland | 90 | 16.2 | 10 | 11.1 (5.5–19.5) | 3 | 3.3 (.7–9.4) | 7 | 7.8 (3.2–15.4) | 59 | 65.6 (54.8–75.3) |

| Romaniaa | 21 | 3.8 | 2 | 9.5 (1.2–30.4) | 1 | 4.8 (.1–23.8) | 1 | 4.8 (.1–23.8) | 10 | 47.6 (25.7–70.2) |

| Russian Fed. | 98 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–3.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–3.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–3.7) | 36 | 36.7 (27.2–47.1) |

| Taiwan | 4 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–60.2) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–60.2) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–60.2) | 1 | 25.0 (.6–80.6) |

| UK – CMD | 13 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–24.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–24.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–24.7) | 6 | 46.2 (19.2–74.9) |

| Total | 556 | 100 | 41 | 7.4 (5.3–9.9) | 14 | 2.5 (14–4.2) | 27 | 4.9 (3.2–7.0) | 320 | 57.6 (53.3–61.7) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; UK, United Kingdom.

a Concerns about data integrity from a single study site in Romania that enrolled 102 subjects arose after completion of the analysis. Because evaluation of data from this site showed no irregularities when compared with the total cohort, and because GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines has no current plans to use the study data to support any regulatory activity, data from this site were included in the present analysis.

b n, no. of subjects in a given category.

Prevalence of Other Respiratory Viruses in Nasal and Throat Samples

Any virus, including RSV and influenza virus, was detected in 320/556 (57.6%) of moderate-to-severe ILI episodes. The highest prevalence of respiratory viruses was observed in the Czech Republic (53/70 [75.7%]), whereas the lowest was in Taiwan (1/4) (Table 3). Detection rates of individual viruses differed between countries but did not display the same pattern as RSV (Supplementary Table 1). The most frequently reported respiratory viruses were influenza A (104/320 positive samples [32.5%]), rhinovirus/enterovirus (82/320 positive samples [25.6%]), RSV (41/320 positive samples [12.8%]), and coronavirus and human metapneumovirus (each with 32/320 positive samples [10.0%]; Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and Other Respiratory Viruses in 320 Nasopharyngeal Samples Positive for any Virus by RT-PCR Positive Samples

| 320 Virus-positive Samples |

||

|---|---|---|

| Categories | na | % (95% CI) |

| RSV | 41 | 12.8 (9.4–17.0) |

| RSV subtype A | 14 | 4.4 (2.4–7.2) |

| RSV subtype B | 27 | 8.4 (5.6–12.0) |

| Influenza A | 104 | 32.5 (27.4–37.9) |

| Influenza A subtype H1 | 2 | 0.6 (.1–2.2) |

| Influenza A subtype H3 | 94 | 29.4 (24.4–34.7) |

| Influenza A subtype H5 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–1.1) |

| Other Influenza A subtype | 8 | 2.5 (1.1–4.9) |

| Influenza B | 15 | 4.7 (2.6–7.6) |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 3 | 0.9 (.2–2.7) |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–1.1) |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 15 | 4.7 (2.6–7.6) |

| Parainfluenza 4 | 6 | 1.9 (.7–4.0) |

| Human Metapneumovirus | 32 | 10.0 (6.9–13.8) |

| Rhinovirus/Enterovirus | 82 | 25.6 (20.9–30.8) |

| Adenovirus | 1 | 0.3 (.0–1.7) |

| Coronavirus | 32 | 10.0 (6.9–13.8) |

| Coronavirus 229E | 3 | 0.9 (.2–2.7) |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 11 | 3.4 (1.7–6.1) |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 10 | 3.1 (1.5–5.7) |

| Coronavirus HKU1 | 8 | 2.5 (1.1–4.9) |

| Coronavirus SARS | 0 | 0.0 (.0–1.1) |

There were 11 cases of multiple viruses detected: RSV + rhinovirus/enterovirus; RSV + Human Metapneumovirus; Influenza B + rhinovirus/enterovirus (2 cases); Influenza A + Parainfluenza 4; rhinovirus/enterovirus + Coronavirus OC43; Influenza A + rhinovirus/enterovirus (3 cases); Influenza A + Influenza B; Influenza A + Coronavirus HKU1.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

a n, no. of subjects in a given category.

Multiple viral infections were detected in 11 ILI episodes. Influenza A and/or B and/or rhinovirus/enterovirus were implicated in all but 1 coinfection (Table 4).

Non-RSV viruses detected in pneumonia episodes were influenza A (all H3; 3/28 [10.7%]), human metapneumovirus (1/28 [3.6%]), and rhinovirus/enterovirus (3/28 [10.7%]; Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of Respiratory Viruses Detected in Moderate-to-Severe Influenza-like Illness (ILI) Episodes, by Disease State

| No. of Episodes (N) | Totala (N = 556) |

Pneumonia (N = 28) |

Hospitalized (N = 64) |

ISS Score >2–3 (N = 490) |

% of + ve Cases Who Were Hospitalized | % of -ve Cases Who Were Hospitalized | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | nb | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | ||

| RSV | 41 | 12.8 (9.4–17.0) | 2 | 7.1 (.9–23.5) | 8 | 12.5 (5.6–23.2) | 35 | 7.1 (5.0–9.8) | 19.5 | 10.9 |

| Influenza A | 104 | 32.5 (27.4–37.9) | 3 | 10.7 (2.3–28.2) | 4 | 6.3 (1.7–15.2) | 98 | 20.0 (16.5–23.8) | 3.8 | 13.3 |

| Influenza B | 15 | 4.7 (2.6–7.6) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 3 | 4.7 (1.0–13.1) | 13 | 2.7 (1.4–4.5) | 20.0 | 11.3 |

| Parainfluenza 1 | 3 | 0.9 (.2–2.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 1 | 1.6 (.0–8.4) | 2 | 0.4 (.0–1.5) | 33.3 | 11.4 |

| Parainfluenza 2 | 0 | 0.0 (.0–1.1) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–5.6) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–.8) | 0.0 | 11.5 |

| Parainfluenza 3 | 15 | 4.7 (2.6–7.6) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 1 | 1.6 (.0–8.4) | 14 | 2.9 (1.6–4.7) | 6.7 | 11.6 |

| Parainfluenza 4 | 6 | 1.9 (.7–4.0) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 1 | 1.6 (.0–8.4) | 5 | 1.0 (.3–2.4) | 16.7 | 11.5 |

| Human Metapneumovirus | 32 | 10.0 (6.9–13.8) | 1 | 3.6 (.1–18.3) | 3 | 4.7 (1.0–13.1) | 29 | 5.9 (4.0–8.4) | 9.4 | 11.6 |

| Rhinovirus/Enterovirus | 82 | 25.6 (20.9–30.8) | 3 | 10.7 (2.3–28.2) | 12 | 18.8 (10.1–30.5) | 71 | 14.5 (11.5–17.9) | 14.6 | 11.0 |

| Adenovirus | 1 | 0.3 (.0–1.7) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–5.6) | 1 | 0.2 (.0–1.1) | 0.0 | 11.5 |

| Coronavirus | 32 | 10.0 (6.9–13.8) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–12.3) | 0 | 0.0 (.0–5.6) | 32 | 6.5 (4.5–9.1) | 0.0 | 12.2 |

| Any virus | 320 | 57.6 (53.3–61.7) | 9 | 32.1 (15.9–52.4) | 32 | 50.0 (37.2–62.8) | 290 | 59.2 (54.7–63.6) | 10.0 | 13.9 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ISS,influenza symptom severity score.

aIncludes 9 episodes for which the hospitalization status of the subject was unknown.

b n, no. of subjects in a given category.

Non-RSV viruses were detected in 24/64 hospitalized cases (Table 5). Hospitalization among RSV-positive moderate-to-severe ILI episodes (8/41 [19.5%]) was about 2-fold more common than hospitalization among episodes positive for any other virus (24/279 [8.6%]) and 5-fold more common compared to influenza A (4/104 [3.8%]), respectively.

The median duration of ILI episodes was 15 days. No clear patterns were seen in terms of episode duration according to virus type, although the numbers were small (data not shown).

Frequency of Respiratory Symptoms According to Virus

The frequency of individual respiratory symptoms in subjects with a single infection with 1 of the 5 most prevalent virus types showed no striking pattern of symptoms according to virus type (Table 6). Fever was most frequent in influenza A infection (72.4%) and least frequent in infections due to rhinovirus/enterovirus (40%). Dyspnea and wheezing were most frequent in RSV infections (51% and 46%, respectively). Cough was present in >90% for all virus types.

Table 6.

Frequency of Symptoms Among Single Virus Infections (Viruses Detected in at Least 30 Cases)

| No. of Episodes (N) | RSV (N = 39) |

Influenza A (N = 98) |

Metapneumovirus (N = 31) |

Rhinovirus/Enterovirus (N = 75) |

Coronavirus (N = 30) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | na | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) |

| Nasal congestion | 28 | 71.8 (55.1–85.0) | 76 | 77.6 (68.0–85.4) | 23 | 74.2 (55.4–88.1) | 58 | 77.3 (66.2–86.2) | 28 | 93.3 (77.9–99.2) |

| Sore throat | 25 | 64.1 (47.2–78.8) | 63 | 64.3 (54.0–73.7) | 20 | 64.5 (45.4–80.8) | 58 | 77.3 (66.2–86.2) | 22 | 73.3 (54.1–87.7) |

| New or worsening cough | 36 | 92.3 (79.1–98.4) | 87 | 88.8 (80.8–94.3) | 28 | 90.3 (74.2–98.0) | 61 | 81.3 (70.7–89.4) | 27 | 90.0 (73.5–97.9) |

| New or worsening dyspnea | 20 | 51.3 (34.8–67.6) | 32 | 32.7 (23.5–42.9) | 8 | 25.8 (11.9–44.6) | 26 | 34.7 (24.0–46.5) | 9 | 30.0 (14.7–49.4) |

| New or worsening sputum production | 27 | 69.2 (52.4–83.0) | 49 | 50.0 (39.7–60.3) | 14 | 45.2 (27.3–64.0) | 33 | 44.0 (32.5–55.9) | 12 | 40.0 (22.7–59.4) |

| New or worsening wheezing | 18 | 46.2 (30.1–62.8) | 30 | 30.6 (21.7–40.7) | 3 | 9.7 (2.0–25.8) | 11 | 14.7 (7.6–24.7) | 8 | 26.7 (12.3–45.9) |

| Fever | 22 | 56.4 (39.6–72.2) | 71 | 72.4 (62.5–81.0) | 17 | 54.8 (36.0–72.7) | 30 | 40.0 (28.9–52.0) | 15 | 50.0 (31.3–68.7) |

| Headache | 32 | 82.1 (66.5–92.5) | 72 | 73.5 (63.6–81.9) | 25 | 80.6 (62.5–92.5) | 57 | 76.0 (64.7–85.1) | 26 | 86.7 (69.3–96.2) |

| Fatigue | 31 | 79.5 (63.5–90.7) | 75 | 76.5 (66.9–84.5) | 21 | 67.7 (48.6–83.3) | 59 | 78.7 (67.7–87.3) | 20 | 66.7 (47.2–82.7) |

| Myalgia | 25 | 64.1 (47.2–78.8) | 69 | 70.4 (60.3–79.2) | 19 | 61.3 (42.2–78.2) | 51 | 68.0 (56.2–78.3) | 23 | 76.7 (57.7–90.1) |

| Feverishness | 18 | 46.2 (30.1–62.8) | 58 | 59.2 (48.8–69.0) | 18 | 58.1 (39.1–75.5) | 36 | 48.0 (36.3–59.8) | 17 | 56.7 (37.4–74.5) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

a n, number of subjects in a given category.

Associations Between Risk Factors and Viral Detection

Exploratory univariate analysis showed no association between RSV detection and age, smoking status, gender, or randomization group (adjuvanted vs nonadjuvanted trivalent influenza vaccine) of the primary INFLUENCE65 study. Factors found to be associated with RSV detection among moderate-to-severe ILI episodes were “high-level care” as defined in Table 1 (odds ratio [OR], 3.5; 95% CI, 1.4–9.2; P = .0103), congestive heart failure (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1–7.4; P = .0223), other cardiopulmonary diseases (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.7, P = .0143), and noninflammatory cerebrovascular/neurological disorders (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.3, P = .0102). These factors, however, were not independently associated with RSV detection. No independent predictor of RSV detection was determined in the multivariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

We used multiplex RT-PCR to detect viral etiologies of moderate-to-severe ILI in elderly influenza-vaccinated community-dwelling elderly adults during 1 winter season from November 2008 to April 2009 in a large international study. Viruses were detected in 57.6% (320/556) of moderate-to-severe ILI episodes, of which approximately one-third were influenza A. RSV, rhinovirus/enterovirus, coronavirus, and human metapneumovirus were also important pathogens in this age group, with RSV detected in 7.4% of samples. Moderate-to-severe ILI episodes that were RSV-positive were more likely to result in hospitalization than other viral respiratory infections; however, influenza vaccination may have attenuated the severity of influenza A in the study population.

The virus detection rate of 57.6% in this study is higher than what has been reported in a number of previous studies [6] and can be at least partially explained by the use of a sensitive multiplex RT-PCR, which can detect 18 different viruses and subtypes. However, it is important to recognize that multiplex RT-PCR may have different analytic sensitivities for the different viruses, which can affect the diagnostic yield. In addition, viral load may vary for specific viral infections with RSV viral load typically low in the upper airways of adults [5, 17, 18]. Another factor that may explain the variability of virus detection rates in the literature is the clinical definition used to trigger swab collection and further laboratory testing. There is currently no universally accepted definition of all ILI or moderate-to-severe ILI, in particular in the elderly population where the clinical presentation may be atypical. We attempted to define moderate-to-severe ILI using objective and subjective criteria, which we felt were relevant to respiratory illnesses rather than minor colds. Fever occurs less commonly in the elderly; our definition of ILI, which did not require the presence of fever, is an important difference from other studies using ILI definitions to evaluate noninfluenza viruses. The inclusion of fever as an obligatory part of the ILI case definition would have excluded around 30%–60% of cases, depending on virus type. The majority of subjects with moderate-to-severe ILI were identified by an ISS >2. Although every attempt was made to capture all cases, proportionally more swabs (up to 44%) were missed from episodes with pneumonia and hospitalization. This may mean that subjects presenting with an ILI that resulted in pneumonia deteriorated so rapidly that no swab could be collected in time. Thus, our data may have missed part of the most severe spectrum of disease (no deaths occurred in the test cohort). Of note, as per protocol, swabs were only to be taken if an ILI occurred. A subject presenting with pneumonia without a preceding ILI as per the protocol definition, would have had no swab taken.

We observed an effect of country on RSV prevalence driven mainly by results from 2 countries (Czech Republic and Russia). This effect probably reflected seasonal variability during the study period, although a cultural effect of family/household structure could also have contributed to the regional differences we observed. Studies in individual countries over multiple seasons and considering different disease severities are needed to more fully understand the regional burden of RSV in the elderly.

One of the limitations of our study is that the primary INFLUENCE65 study was designed to evaluate ILI associated with influenza infection, not all causes of respiratory infection. Even though the definition of an ILI was broad, study physicians may have been biased in their clinical assessment and decision whether or not to take a swab depending on whether influenza was active in their community. Other potential limitations of the study include that all subjects received influenza vaccination, which is likely to have reduced influenza infection rates. We were not able to distinguish simple viral infection from combined viral and bacterial infections. Small numbers of RSV positive subjects meant that subanalyses by pneumonia and hospitalization status were unable to identify meaningful associations. Finally, hospitalization status was unknown for 9 (<2%) moderate-to-severe ILI episodes.

We identified no independent predictor of RSV detection. However, another study found that RSV infection was more frequent among adults with congestive heart failure or chronic pulmonary disease [8]. Elderly individuals with chronic cardiac or respiratory disease are therefore likely to benefit most from RSV prevention.

Few prospective studies have evaluated etiologies of acute respiratory infections in community-based elderly individuals. In one prospective US study conducted over 4 winter seasons, RSV was detected (using RT-PCR) annually in up to 3%–10% of elderly individuals living in the community, with the illness preventing normal daily activities in 42% of patients [8]. A prospective study conducted in community-dwelling elderly persons in the United Kingdom detected RSV antibodies (using complement fixation) in 3% of 497 illnesses among the 533 persons followed for 2 winter seasons [10]. A prospective study in Brazil that relied on passive reporting of acute respiratory infections by community-dwelling elderly detected a virus (using RT-PCR) in 15/49 samples (30.6%) [19]. Rhinovirus/enterovirus was detected in all cases but 1 (human metapneumovirus), and no RSV was identified.

In our study, RSV was detected by RT-PCR in 7.4% of severe ILIs in elderly community-dwelling adults and was more prevalent in hospitalized patients than in patients with pneumonia or an ISS score >2. Although our study was not designed to determine incidence rates or evaluate disease burden, the results are consistent with previous reports suggesting that RSV is an important cause of moderate-to-severe ILI and may be associated with hospitalization in the elderly [20–22].

The results of our study cannot be generalized to all ILI in the elderly because moderate-to-severe ILI represented only 10% of all ILI identified in eligible study sites. In addition, our study was limited to 1 year, and evaluations over multiple seasons may more accurately reflect global RSV impact. We observed country-to-country variability in RSV detection, with the highest proportion of RSV-positive episodes occurring in the Czech Republic and Poland. Such variation will require further study over time to understand the implications of these findings. Despite these limitations, this is the first global study to our knowledge providing data on RSV disease in the elderly. Consistent with reports from North America, our study confirms that RSV is an important respiratory pathogen in older adults.

In conclusion, assessment of RSV prevalence using multiplex RT-PCR in influenza-vaccinated subjects aged ≥65 years from 14 countries with moderate-to-severe ILI showed that RSV was implicated in 7.4% of respiratory illnesses. Our study illustrates the importance of RSV and other respiratory viruses as causes of serious respiratory illness affecting older adults around the globe. Thus, in addition to influenza prevention, prevention of viral infections such as RSV could decrease severe illnesses in the elderly, particularly those at increased risk of the complications of viral respiratory tract infections.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Francois Haguinet (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for review of the statistical analysis plan and results, Catherine Cohet (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for her initial work on the protocol, and Joanne Wolter (Independent Medical writer, paid by GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for preparing the first draft of the article.

The authors also thank Sylvie Hollebeeck (XPE Pharma & Science on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for publication coordination and management, Dorien Geypens (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for global clinical study management, Taara Madhavan (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) who was the scientific writer of the protocol, and Clara van der Zee (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) who was the scientific writer of the study report.

The authors also acknowledge the following principal investigators from INFLUENCE65 study centres that contributed samples to this analysis: P.-H. Arnould, Y. Balthazar, M. De Meulemeester, P. Muylaert, L. Tilley, D. Van Riet (Belgium); F. Blouin, A. Chit, M. Ferguson (Canada); I. Koort, K. Maasalu, L. Randvee, J. Talli (Estonia); J.-F. Foucault, D. Saillard, (France); A. Benedix, B. A. Bergtholdt, F. Burkhardt, A. Dahmen, R. Deckelmann, H. Dietrich, T. Eckermann, K. Foerster, H. Folesky, M. Golygowski, C. Grigat, A. Himpel-Boenninghoff, P. Hoeschele, B. Huber, S. Ilg, J.-P. Jansen, U. Kleinecke-Pohl, A. Kluge, W. Kratschmann, J. Kropp, A. Linnhoff, I. Meyer, B. Moeckesch, G. Plassmann, E. Reisinger, T. Schaberg, F. Schaper, B. Schmitt, H. Schneider, T. Schwarz, K. Tyler, J. Wachter, H. K. Weyland, D. Züchner (Germany); M. L. Guerrero, A. Mascareñas de Los Santos, N. Pavia-Ruz (Mexico); W. Gadzinski, J. Holda, E. Jazwinska-Tarnawska, Z. Szumlanska (Poland); A. Neculau, D. Toma; A. Vitalariu (Romania); E. Gorodnova, O. Perminova, V. Semerikov (Russian Federation); P.-C. Yang (Taiwan); E. Abdulhakim, S. Rajanaidu (UK).

The authors thank the following individuals from GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines: A. Caplanusi, C. Claeys, B. Innis, M. Kovac, (INFLUENCE65 Vaccines Clinical Study Support), F. Allard, N. Houard, K. Walravens (INFLUENCE65 laboratory partners), and W. Dewé, C. Durand, M. El Idrissi, M. Oujaa (INFLUENCE65 statistical analysis partners). The authors acknowledge the Members of the Independent Data Monitoring Committee, in particular, J. Claassen, A. Grau, R. Konior and F. Verheugt; and the Members of the Adjudication Committee, in particular, M. Betancourt-Cravioto, D. Fleming and W. J. Paget.

Financial support. This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was involved in all stages of the conduct and analysis of the studies included in this pooled analysis. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also funded all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present article. All authors participated in the design or implementation or analysis, and interpretation of the study and in the development of this article. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission. The corresponding author was responsible for submission of the publication.

Potential conflicts of interest. M. E., G. R.-P., F. G., P. K., O. L., G. L.-R., S. M., and J. H. R. report grants from the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies (GSK) to their respective institutes for the conduct of clinical trials. M. E. and J. M. disclose having received support from GSK for travel and accommodations to attend the meetings of the Publication Steering Committee for the Influence65 trial. J. M. reports personal fees from GSK, Sanofi, MedImmune, Merck, Abott Pharmaceuticals, Merck Frosst, Sanofi, the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, World Health Organization, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, as well as grants from CIHR and NIH NIAID. In addition, J. M. declares having a patent entitled ‘Methods of Determining Cell Mediated Response’ licensed to AMRIC (Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada). G. L.-R. reports having received consultancy fees from GSK in the field of vaccine adjuvantation, influenza and other vaccines, and from Immune Targeting Systems in the field of influenza and HBV vaccine development. O. L. reports having also received grants from vaccine manufacturers other than the commercial entity that sponsored this study. S. M. discloses having received grants and personal fees from GSK during the conduct of the study, and other grants and personal fees from GSK, Pfizer Canada, Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, Merck, outside the present work. A. N. reports having received honoraria from GSK for educational lectures and for performing clinical trials. A. F. reports grants from Sanofi Pasteur, Astrazeneca, and ADMA, Inc, as well as personal fees from Novavax, Retroscreen, Janssen, Hologic and ADMA, Inc, outside the submitted work. X. D. discloses having received grants from Pfizer outside the submitted work. S. S. R., J.-M. D., L. O., S. D., and S. T. are employees of GSK, and J.-M. D., L. O., and S. T. report ownership of GSK stock options. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Larbi A, Franceschi C, Mazzatti D, Solana R, Wikby A, Pawelec G. Aging of the immune system as a prognostic factor for human longevity. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:64–74. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuno O, Kataoka H, Takenaka R, et al. Influence of age on symptoms and laboratory findings at presentation in patients with influenza-associated pneumonia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:322–5. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Govaert TM, Dinant GJ, Aretz K, Knottnerus JA. The predictive value of influenza symptomatology in elderly people. Fam Pract. 1998;15:16–22. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.She RC, Polage CR, Caram LB, et al. Performance of diagnostic tests to detect respiratory viruses in older adults. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;67:246–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talbot HK, Falsey AR. The diagnosis of viral respiratory disease in older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:747–51. doi: 10.1086/650486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011;377:1264–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jartti L, Langen H, Söderlund-Venermo M, Vuorinen T, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. New respiratory viruses and the elderly. Open Respir Med J. 2011;5:61–9. doi: 10.2174/1874306401105010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1749–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:371–84. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.371-384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson KG, Kent J, Hammersley V, Cancio E. Acute viral infections of upper respiratory tract in elderly people living in the community: comparative, prospective, population based study of disease burden. BMJ. 1997;315:1060–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElhaney J, Beran J, Devaster J-M, et al. AS03-adjuvanted versus non-adjuvanted inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine against seasonal influenza in elderly people: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:485–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70046-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborne RH, Norquist JM, Elsworth GR, et al. Development and validation of the Influenza Intensity and Impact Questionnaire (FluiiQTM) Value Health. 2011;14:687–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vesikari T, Beran J, Durviaux S, et al. Use of real-time polymerase chain reaction (rtPCR) as a diagnostic tool for influenza infection in a vaccine efficacy trial. J Clin Virol. 2012;53:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahony J, Chong S, Merante F, et al. Development of a respiratory virus panel test for detection of twenty human respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR and a fluid microbead-based assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2965–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02436-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merante F, Yaghoubian S, Janeczko R. Principles of the xTAG respiratory viral panel assay (RVP Assay) J Clin Virol. 2007;40(Suppl 1):S31–5. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(07)70007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleiss J, Levin B, Paik M. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falsey AR, McCann RM, Hall WJ, Criddle MM. Evaluation of four methods for the diagnosis of respiratory syncytial virus infection in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:71–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mlinaric-Galinovic G, Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in the elderly. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:777–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01701518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe ASA, Carraro E, Candeias JMG, et al. Viral etiology among the elderly presenting acute respiratory infection during the influenza season. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44:18–21. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han LL, Alexander JP, Anderson LJ. Respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia among the elderly: an assessment of disease burden. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:25–30. doi: 10.1086/314567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schanzer DL, Langley JM, Tam TWS. Role of influenza and other respiratory viruses in admissions of adults to Canadian hospitals. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2008;2:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin MR, Coffey CS, Neuzil KM, Mitchel EF, Jr, Wright PF, Edwards KM. Winter viruses: influenza- and respiratory syncytial virus-related morbidity in chronic lung disease. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1229–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.