Abstract

Lipid peroxidation products such as 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) are known to be increased in response to oxidative stress, and are known to cause dysfunction and pathology in a variety of tissues during periods of oxidative stress. The aim of the current study was to determine the chronic (repeated HNE exposure) and acute effects of physiological concentrations of HNE towards multiple aspects of adipocyte biology using differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Our studies demonstrate that acute and repeated exposure of adipocytes with physiological low concentrations of HNE is sufficient to promote subsequent oxidative stress, impaired adipogenesis, alter the expression of adipokines, and increase lipolytic gene expression and increase FFA release. These results provide an insight in to the role of HNE induced oxidative stress in regulation of adipocyte differentiation and adipose dysfunction. Taken together, these data indicate a potential role for HNE promoting diverse effects towards adipocyte homeostasis and adipocyte differentiation, which may be important to the pathogenesis observed in obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: adipose, adipogenesis, Insulin resistance, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity, oxidative stress

Introduction

Adipose tissue serves an essential role in regulating energy homeostasis, allowing for efficient regulation of energy homeostasis, in the face of variable periods of energy expenditure and food intake. In contrast to the beneficial aspects of adipose tissue like energy storage, adipose tissue during conditions such as obesity contributes to the development of metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance [1–3]. Increases in oxidative stress are associated with adipose accumulation [4] and found to play a role in the pathophysiology of various diseases [5–7]. Oxidative tress is also linked to altered glucose regulation [8–10]. Taken together, these data suggest a possible role for oxidative stress during the development of obesity, as well as in the complications of obesity.

Adipocytes are rich in readily oxidizable lipids, and thus vulnerable to oxidative stress and lipid oxidation [4, 11]. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) is an α, β-unsaturated aldehyde, a major product of lipid peroxidation process [12]. HNE rapidly forms adduct with biological molecules such as proteins and DNA and leads to their impaired function [13–15]. Toxic concentrations of HNE are found to induce apoptosis in cells [16]. Studies indicate that physiological concentrations of HNE can act as a growth regulating factor by modulating cell growth and differentiation [17–19]. HNE at physiological concentrations is also known to serve as signaling molecule in variety of cellular responses including inflammatory response, proteasomal-mediated protein degradation, mitochondria function, insulin signaling and apoptosis [16, 20–25].

HNE is considered as biomarker of cellular oxidative stress and previous reports indicate that the levels of HNE in the low micromolar concentrations under physiological conditions in cells, reaching 5 mM under pathophysiological conditions [19,26–29], while the concentrations in human plasma were reported to range from 10 nM – 10 μM [30–31]. Increased levels of HNE and HNE modifed proteins have been reported in different clinical settings including aging, diabetes, obesity and neurodegenerative diseases [2, 14, 32]. Recent studies have linked HNE protein modification to the impaired function of proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, insulin signaling, antioxidant levels and suppression of inflammation [14, 26, 33–34] in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. These data raise the potential for HNE to serve as a potent modulator of adipose biology.

Differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes is characterized by the expression of different adipogenic transcription factors such as PPARγ (a master regulator of adipogenesis), C/EBPα, aP2, increased glucose uptake and altered adipokine production [35–37]. Altered expression of adipogeneic transcription factors and adipokines has been implicated in adipose dysfunction during obesity [2,38–40]. Increased oxidative stress has been shown to inhibit adipogenesis [41], impair glucose uptake [9, 26, 34] and alter adipokine production [4, 42] in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

The effects of repeated and acute exposure of physiological levels of HNE have not been established in adipose cells. In this study, we demonstrate that treatment of mature adipocytes (acute) and differentiating preadipocytes (repeated exposure) with physiological levels of HNE induces oxidative stress, decreases lipid content, and alters adipogenic and adipokine expression and increases free fatty acid release. Repeated exposure with physiological levels of HNE impaired the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. These data raise the potential for HNE in promoting oxidative stress and multiple modes of pathogenesis in adipose tissue during conditions such as obesity.

Materials

The antibodies against β-actin were purchased from SantaCruz (CA, USA), Antibodies against Glut4, C/EBPα and PPARγ were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Incorporated (Danvers, MA, USA). The antibodies against aP2 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). HNE [4-Hydroxy-2- nonenal) was purchased from Cayman chemicals (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). ELISA kits for Adiponectin and Leptin were purchased from R&D systems, Inc. [Minneapolis, MN, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing high glucose and glutamine, fetal bovine serum, calf serum, trypsin and antibiotics penicillin G/streptomycin were purchased from Fisher Scientifics (Pittsburgh, PA). DHE (Di Hydro Ethidium) was purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other items and chemicals including Insulin, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, dexamethasone, propidium iodide and Oil Red O stain were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO, USA). All electrophoresis and immunoblot reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). All the HRP conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Vector Laboratories, USA.

Adipocyte differentiation

Murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM high glucose containing 10% calf serum and antibiotics (100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). To obtain fully differentiated adipocytes, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were plated and grown in 6 well plates to 1 day post confluence and induced to differentiate by changing the medium to DMEM containing 10% FBS and 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM dexamethasone and 1.7 μM insulin (MDI). After 48 hours, medium was replaced with DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% FBS, pen/strep and 0.425 μM insulin. Thereafter medium was replaced every 2 days with DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. The extent of differentiation for adipocyte cultures in the present study is indicated by days, which refers to days post induction with MDI medium. Day 9 (post MDI induction) adipocytes were used for acute HNE treatment studies. Control cells not treated with HNE, were treated with vehicle.

To study the effect of HNE on lipid accumulation in adipocytes, 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation in to adipocytes was induced as described above with the addition of indicated amounts of HNE to the medium for 7 days. Fresh medium containing vehicle or HNE was replaced every 2 days. The lipid accumulation in day 7 cells after induction of differentiation was observed by staining the cells with Oil Red O stain. Day 7 adipocytes (post MDI induction) differentiated in the absence or presence of (1 or 10 μM) HNE were used for chronic HNE treatment studies. Control cells not treated with HNE, were treated with vehicle.

Oil Red O staining

Oil Red O staining was performed to visualize the lipid accumulation in differentiating adipocytes following the treatment with HNE. Cells were gently washed with PBS and fixed in 10% of formalin for 1 hour followed by incubation in 60% isopropanol for 5 minutes. After 5 minutes, 60% isopropanol was removed and then the cells were incubated with filtered Oil Red O working solution for one hour at room temperature. Cells were washed gently with distilled water to clear the background and analyzed under microscope. Oil Red O working solution was made by mixing 4 parts of Oil Red O stock solution (0.5% w/v in 99% Isopropanol) to 1 part of water.

Cell viability assay using Propidium Idodide

Following the treatment with HNE, adipocytes were stained with propidium idodide at a concentration of 1μg/μl, and the effect of HNE on cell viability was analyzed under fluorescence microscope. Percent cell death was calculated using number of dead cells (PI stained cells) to total number cells (Hoechst stained cells). Percent cell viability was then calculated from percent cell death.

Hoechst staining

Following the treatment with HNE, adipocytes were stained with fluorescent DNA-binding dye, Hoechst 344 at a concentration of 1μg/μl, and the effect of HNE on nuclei was visualized under fluorescence microscope.

Dihydroethidium staining for ROS

Dihydroethidium staining for intracellular reactive oxyen species (ROS) was performed by incubating the cells for 30 min with 10 μM dihydroethidium dye (solubilized in DMSO) and then analyzed for dihydroethidium oxidation by visual microscopy.

Western blotting and analysis of oxidized proteins

The protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with specified antibodies. HNE modified proteins in cell lysates were analyzed by western blot analysis. Antibody against HNE was kindly provided by Dr Luke Szweda (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation). Briefly, the proteins were transferred on to PVDF membrane and the membrane was incubated in freshly made solution containing 250 mM sodium borohydride in 100 mM MOPS, pH 8.0 for 15 minutes, which was done to chemically reduce the adduct for antibody recognition. After 15 minutes of incubation, the membrane was washed for 3 times with water and another 3 times with PBS, with 5 minutes used for each washing step. The membrane was blocked in 5% milk for 1 hour and then incubated for overnight with 1:2000 dilution of HNE antibody in 5% milk. The membrane was developed using ECL reagent.

Protein carbonyl levels were analyzed using Oxyblot kit (Millipore) as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, cell or tissue lysates were derivatized with DNPH (2, 4-Dinitrophenyl hydrazine) and then the derivatized products were detected by the western blot analysis as described by the manufacturer.

Glucose uptake

Glucose uptake was carried out as described previously [43] with minor modifications. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were first washed twice in PBS and pre-incubated in serum free medium for overnight with 1% BSA, and then treated with 50 μM of HNE for 2 hours. After that, cells were incubated in PBS containing 200 ηM insulin for 20 minutes and then incubated in PBS containing 0.1 mM 2-deoxy-glucose and 0.5 μCi/ml of deoxy-D-glucose, 2-[1–14C]- (Cat# NEC495A050UC, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) for 5 min. The cells were washed 2X with ice cold PBS, solubilized in 0.4 ml of 1% SDS and [14C]-glucose uptake was measured using Beckman LS6500 Scintillation counter.

Fatty acid uptake

Fatty acid uptake was carried out as described previously [43] with minor modifications. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were first pre-incubated for 3 h in Krebs-Ringer’s HEPES (KRH) buffer (pH 7.4) containing 120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, and 5.4 mM glucose and then treated with 50 μM of HNE for 2 hours. Following treatment, cells were stimulated with 200 ηM insulin for 20 minutes. Fatty acid uptake was initiated by incubating cells in KRH buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5.4 mM glucose and 0.5 μCi/ml Oleic Acid, [1–14C]- (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) along with unlabelled Oleic acid (free fatty acid) and BSA for 5 min. The ratio of FA/BSA used in this assay was adjusted to generate a free fatty acid concentration of 5 ηM. The cells were washed 2X with ice cold PBS, solubilized in 0.4 ml of 1% SDS and [14C]-oleic acid uptake was measured using Beckman LS6500 Scintillation counter.

Estimation of free fatty acid levels

Free fatty acid levels in the cell medium were estimated using Fatty Acid Detection Kit from Zen Bio, Inc. (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Culture medium was collected following acute HNE treatment on day 9 adipocytes or following chronic HNE treatment on day 7 adipocytes. Free fatty acid levels in culture medium were estimated as described by the manufacturer.

Quantitative real-time PCR studies

Total RNA from 3T3-L1 adipocytes was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cells were lysed in RLT lysis buffer and total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. The corresponding cDNA was made from 2 μg of extracted total RNA by M-MuLV transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) using 20 μl of the reverse transcription system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis, aliquots of cDNA were subjected to qPCR in 20 μl of 1X Brilliant II QPCR Master mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), 1X primers and TaqMan probe (6-FAM/ZEN/IBFQ mode), and 10 ηg of cDNA. Primers and probes for PPARγ, C/EBPα, Pref1, aP2, HSL, LPL and GADPH for Prime-Time Predesigned qPCR Assay system were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). GADPH was used as an internal reference gene. PCR amplifications were performed as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 50 cycles each with 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 45 s using an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detector according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative mRNA expression of each gene was represented as ddCT (change in fold expression over respective control) from the mean ± SE of 5 (η=5) independent set of samples.

Results

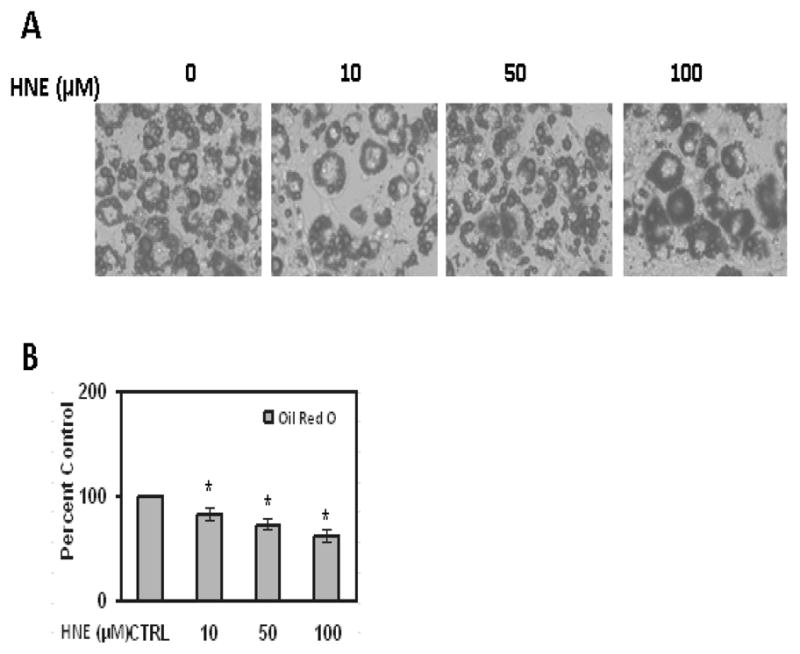

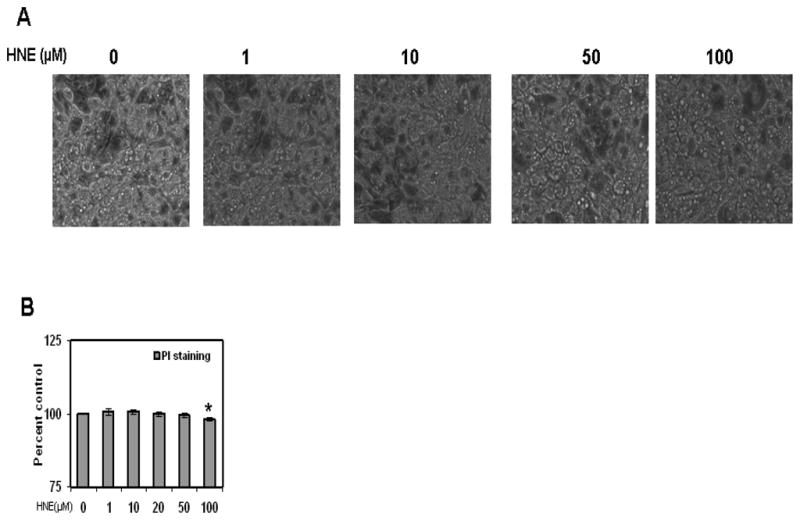

Acute HNE treatment decreases lipid content in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes

To determine the acute effects of HNE on lipid content of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes (day 9 post induction), cells were treated with HNE for overnight (15 hrs) and analyzed by Oil Red O staining. Acute treatment of adipocytes with HNE showed decrease in Oil Red O staining, consistent with increasing amounts of HNE decreasing lipid content in adipocytes (Figure 1).These findings were supported in both microscopic analysis, as well as analysis using plate reader measurements of lysed cells. Adipocyte cell viability was measured using propidium iodide (PI) and Hoechts staining following HNE treatment. Acute treatment of adipocytes with 10 μM HNE for overnight did not have significant toxic effect on viability of adipocytes (Figure 2). However, significant cell death was observed at 100 μM concentration of HNE with overnight treatment compared with the vehicle treated control cells (Figure 2). Control cells treated with vehicle in the absence of HNE did not have any significant effect on the cell viability and lipid content when compared with the adipocytes not treated either with vehicle or HNE (Figure 2). Together, these results show that treatment with physiological concentrations of HNE promotes decreased lipid content in mature adipocytes.

Figure 1.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on lipid accumulation of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. (A) Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE for 15 h and then analyzed by Oil red O staining to visualize the effect of HNE on lipid accumulation as described in methods (B) Oil red O-stained lipid amount was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

Figure 2.

Adipocyte viability following HNE treatment. Mature adipocytes were measured for cell viability using visual inspected of cell morphology, propidium iodide (PI) staining (for necrotic cells), and Hoechts staining (to determine total number of cells in field). The percent cell viability was calculated using number of dead cells (PI stained cells) versus total number cells (Hoechst stained cells). *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

Acute HNE treatment stimulates adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression in mature adipocytes

To evaluate the effects of HNE on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression in mature adipocytes, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE and analyzed for gene expression via Real Time-PCR. Acute treatment of adipocytes with physiological concentrations of HNE (1–10μM) increased the levels of PPARγ, C/EBPα, aP2 (adipogeneic genes), HSL and LPL (lipolytic genes) (Figure 3). Interestingly, higher concentrations of HNE were observed to generally not induce adipogenic gene expression (Figure 3). Taken together, these results show that physiological levels of HNE stimulates adipogenic gene expression, while at the same time inducing lipolytic gene expression.

Figure 3.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression of mature adipocytes. Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE for 15 h and then analyzed for the effect of HNE on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression levels using RT-PCR. (A) PPARγ (B) C/EBPα (C) aP2 (D) HSL and (E) LPL. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

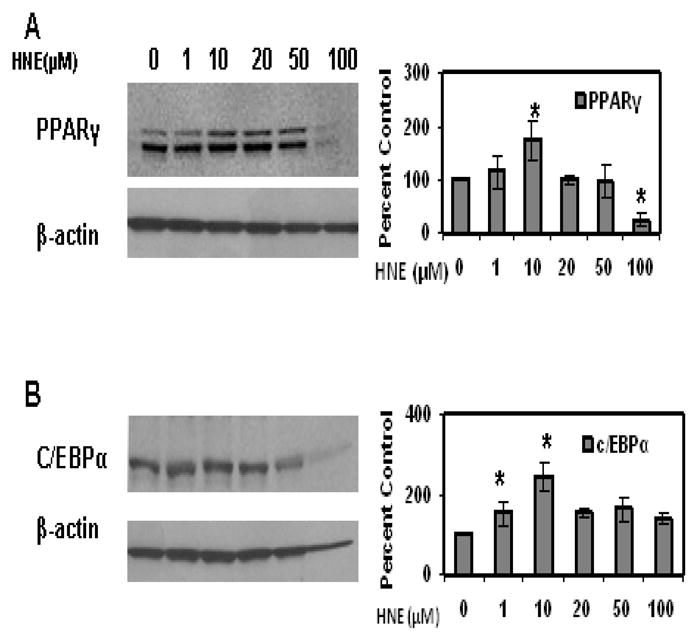

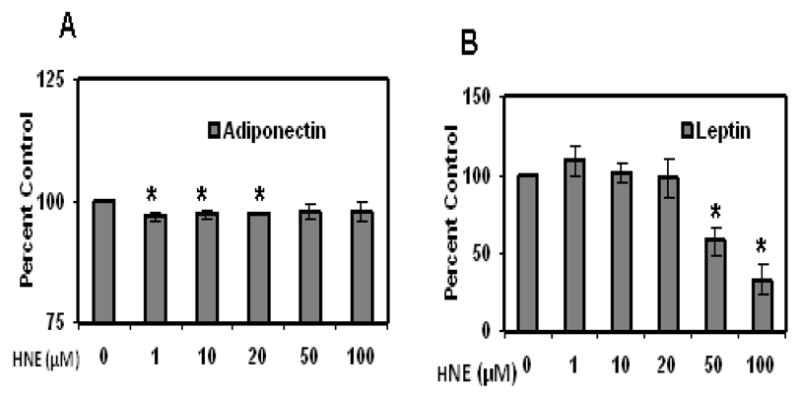

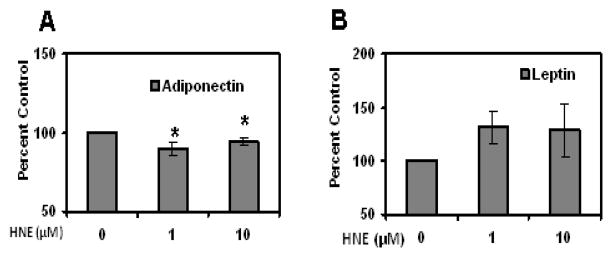

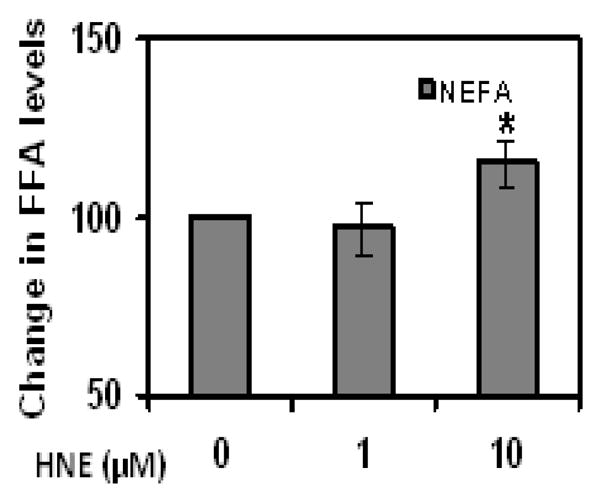

Acute HNE treatment alters adipogenic proteins and adipokines in mature adipocytes

To determine whether acute HNE treatment has any effect on expression of adipogenic proteins such as PPARγ and C/EBPα in mature adipocytes, cells were treated with HNE for overnight and analyzed by Western blot analysis. As shown in (Figure 4), acute treatment of adipocytes with physiological concentrations of HNE (1–10μM) increased the levels of PPARγ and C/EBPα, while higher doses of HNE decreased the levels of these proteins. Acute treatment of adipocytes with physiological concentrations of HNE decreased the levels of adiponectin in mature adipocytes, but did not significantly alter the expression of leptin levels (Figure 5). Acute Treatment of mature adipocytes with HNE resulted in increased release of free fatty acids (FFA) in the culture medium (Figure 6). These results indicate that acute exposure of adipocytes to HNE alters the levels of adipogeneic, adipokine expression and increase FFA release.

Figure 4.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on adipogenic protein expression of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE for 15 h and then analyzed for the effect of HNE on adipogenic protein expression using western blot analysis. (A) PPARγ (B) C/EBPα. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the presented graphs.

Figure 5.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on adiponectin and leptin levels of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE for 15 h and then the cell medium was analyzed for adipokine levels using ELISA. (A) Adiponectin and (B) Leptin. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

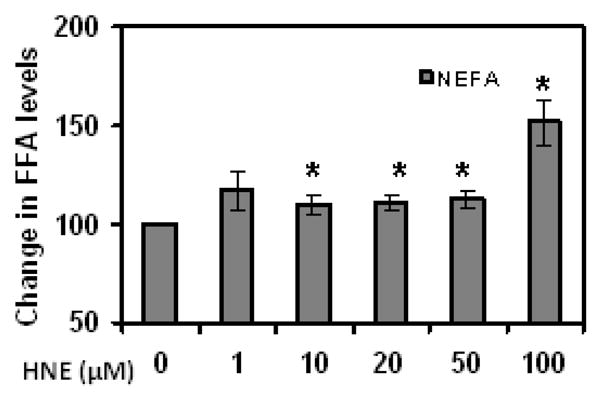

Figure 6.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on free fatty acid levels of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Levels of free fatty acids (FFA) in the culture medium of day 9 adipocytes, following acute HNE treatment for 15 h, were measured as described in methods. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Acute HNE treatment alters Glucose and fatty acid uptake in mature adipocytes

In order to determine whether acute HNE treatment has any effect on glucose and fatty acid uptake in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes, cells were treated with HNE for 2 hours following overnight serum deprivation and analyzed for glucose and fatty acid uptake as described in methods. Treatment of adipocytes with 50 μM HNE for 2hours did not show any significant effect on the cell viability and lipid content of adipocytes. HNE treatment resulted in decreased insulin stimulated glucose and fatty acid uptake as compared to cells not receiving insulin stimulation (Figure 7). It should be noted here that acute HNE treatment on adipocytes for 2 hours did not have significant effect on oxidative stress levels, cell survival and adipogenic transcription factors.

Figure 7.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on glucose uptake, fatty acid uptake of mature adipocytes. Day 9 adipocytes were treated with 50μM of HNE for 2 hours after overnight serum deprivation and then glucose and fatty acid uptake was examined as described in methods. (A) Glucose uptake (B) Fatty acid uptake (Oleic Acid). Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. Treatment with 50μM HNE for 2h did not have any toxic effect on adipocytes viability. *P≤0.05 compared with insulin stimulated untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes. **P≤0.05 compared with unstimulated and untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

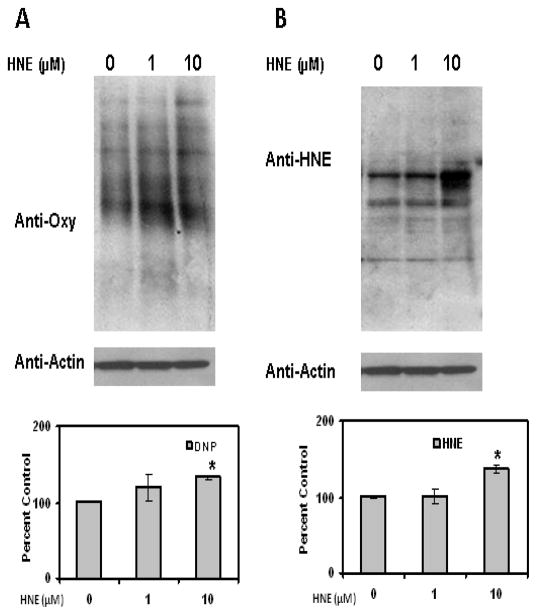

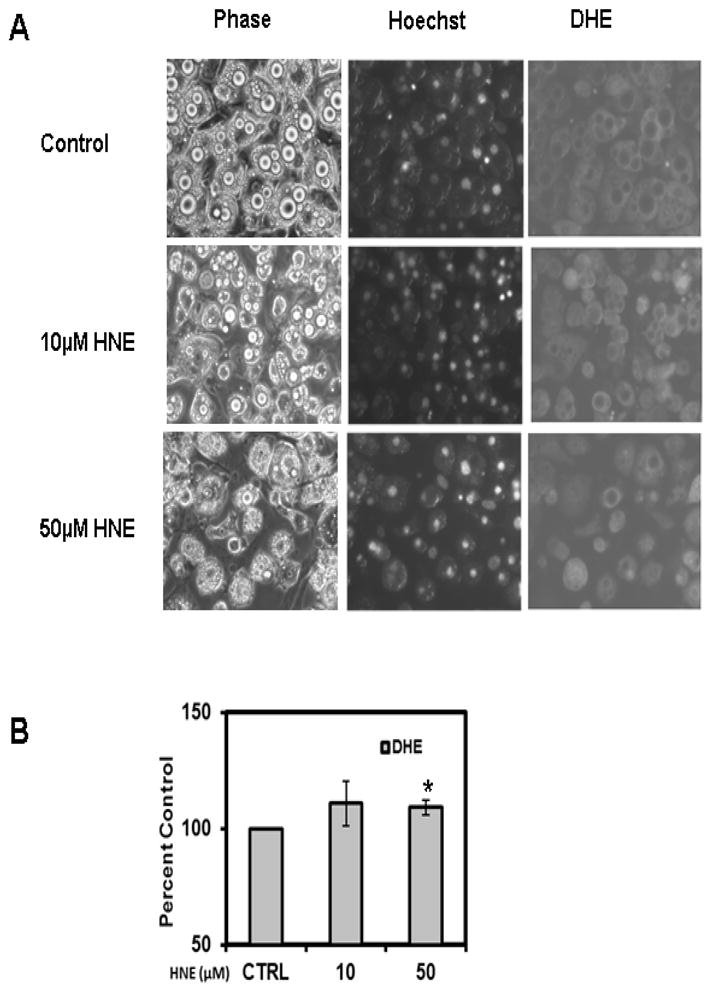

Acute HNE treatment increases intracellular ROS and protein oxidation levels in mature adipocytes

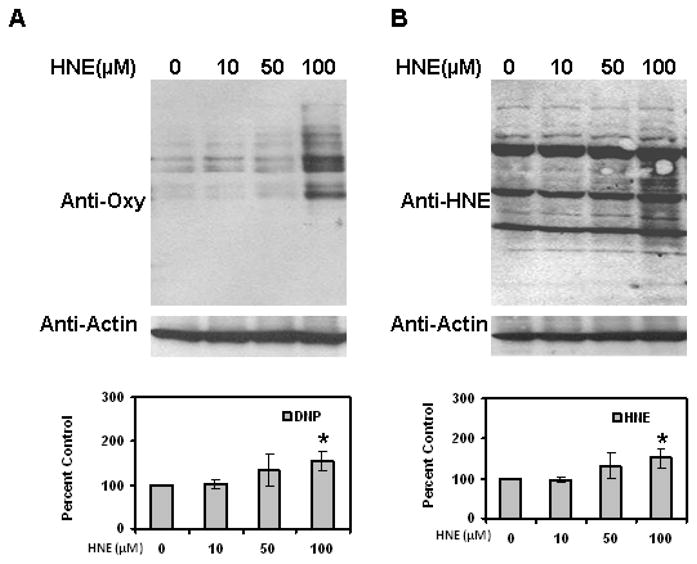

To evaluate whether HNE increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in adipocytes, cells were treated with HNE and analyzed by DHE staining. DHE reacts with reactive oxygen species (ROS) to form the red fluorescent adducts ethidium and oxy-ethidium (product of the reaction of DHE with superoxide) and allow for the quantification of oxidative stress in cells. Acute treatment of adipocytes with physiological levels of HNE resulted in increased levels of ROS (Figure 8). Acute HNE treatment of adipocytes also resulted in significant increase in the amount of oxidized proteins (Figure 9), while at the same time inducing sustained increase in HNE-modified proteins (Figure 9). Treatment of adipocytes with 10, 50 or 100 μM HNE for 4 hrs did not show any significant effect on the cell viability of adipocytes as previously reported by others [26]. These results are consistent with acute exposure to physiological levels of HNE inducing oxidative stress in mature adipocytes.

Figure 8.

Effects of acute HNE treatment on intracellular ROS levels of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of HNE for 4 h and then analyzed by (A) Hoechst and DHE staining as described in methods section (B) Quantification of ROS induced by HNE treatment (using NIH-Image J software). Treatment of adipocytes with 10, 50 or 100μM HNE for 4h did not have any toxic effect on adipocytes viability. Results represent four sets (n=4) of experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with insulin stimulated untreated 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Figure 9.

Effects of acute HNE on protein oxidation levels in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mature adipocytes were treated with increasing amounts of HNE for 4 h and then cell lysates were analyzed for the levels of (A) oxidized and (B) HNE-modified proteins using western blotting analysis. Results represent the means of four sets (n=4) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 9 day adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the presented graphs.

Repeated exposure to HNE treatment decreases lipid accumulation in differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes

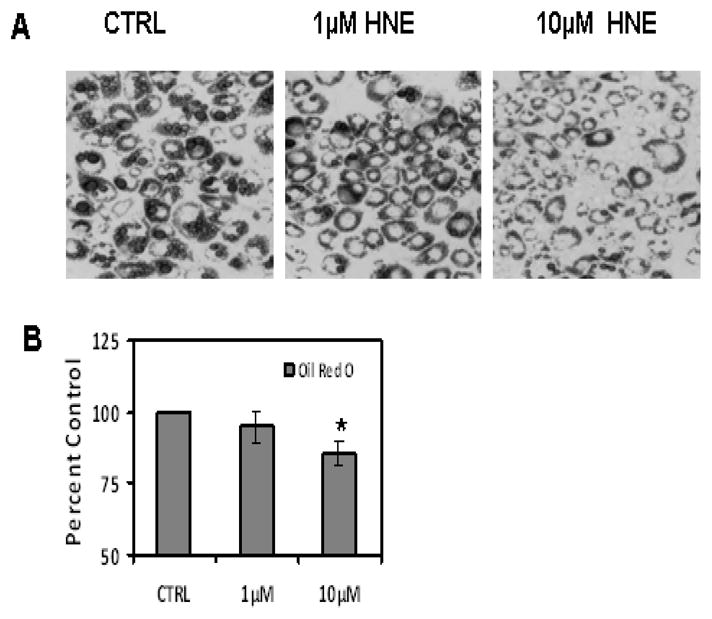

To determine the effects of repeated HNE exposure on lipid accumulation and differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, cells were induced for differentiation in the absence or presence of HNE (1 or 10μM) for 7 days and analyzed by Oil Red O staining as described in methods. Repeated treatment of adipocytes with 10μM HNE for 7 days resulted in decreased lipid accumulation which was confirmed by both microscopic analyses (Figure 10) as well as with quantification of Oil Red O stained lipid content in treated adipocytes (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Effects of repeated HNE treatment on lipid accumulation of differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were induced for adipocyte differentiation as described under materials and methods with the addition of indicated amounts of HNE to the medium for 7 days (A) day 7 adipocytes were analyzed with oil red O staining to visualize the effects of HNE on lipid accumulation (B) Oil red O-stained lipid amount in cells was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm after extraction with Isopropanol. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of experiments done under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated day 7 adipocytes.

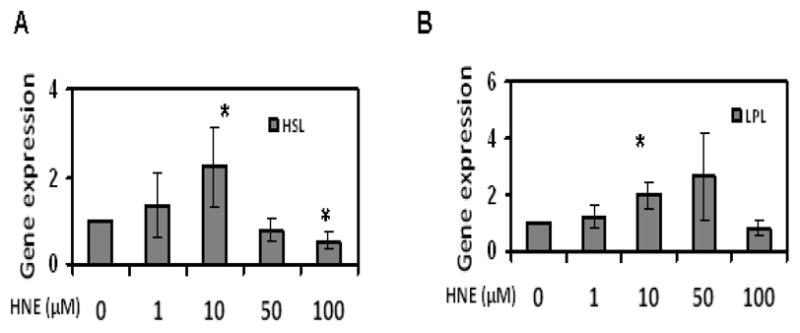

Repeated HNE treatment increases adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression in differentiating adipocytes

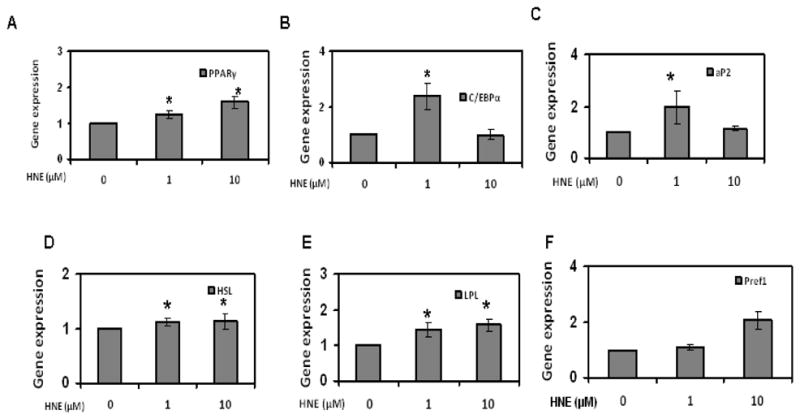

To evaluate the effects of repeated HNE treatment on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression in differentiating adipocytes, cells chronically exposed to HNE were analyzed by RT-PCR. Chronic treatment of differentiating adipocytes with 1 μM HNE stimulated the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα, aP2 (adipogeneic genes), while 10 μM HNE treatment did not significantly change the adipogeneic gene expression (Figure 11). Interestingly, 1 and 10 μM HNE increased the gene expression of HSL and LPL consistent with the presence of increased lipolysis. Taken together, these results indicate that adipogeneic and lipolytic gene expression are altered by repeated exposure to physiological levels of HNE in differentiating adipocytes.

Figure 11.

Effects of repeated HNE treatment on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression of differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were induced for adipocyte differentiation as described under materials and methods with the addition of indicated amounts of HNE to the medium for 7 days and then analyzed for the effect of HNE on adipogenic and lipolytic gene expression levels using RT-PCR. (A) PPARγ (B) C/EBPα (C) aP2 (D) HSL (E) LPL and (F) Pref1. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared to untreated 7 day 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

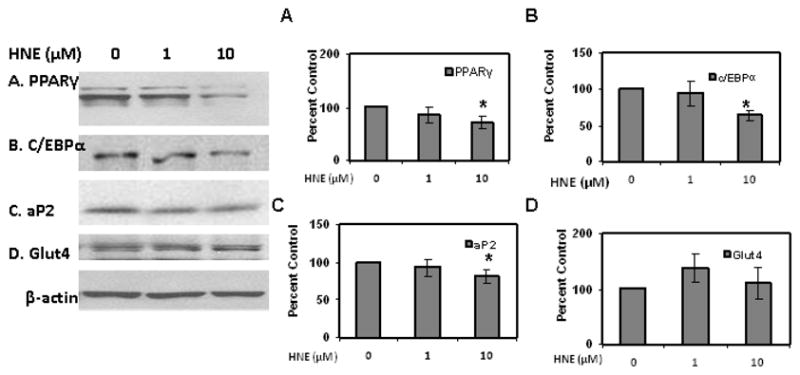

Repeated HNE treatment alters adipogenic, adipokine protein expression and increases FFA release in differentiating adipocytes

As shown in (Figures 12 & 13), repeated treatment of differentiating adipocytes with physiological concentrations of HNE decreased the levels of PPARγ, C/EBPα, aP2 , Glut4 and adiponectin levels as compared to cells not exposed to HNE. Chronic HNE treatment resulted in an increase in FFA levels in the cell medium of differentiating adipocytes (Figure 14). These results indicate a potential role for physiological concentrations of HNE modulating adipocyte differentiation and adipogenic protein expression.

Figure 12.

Effects of chronic HNE treatment on adipogenic protein expression of differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were induced for adipocyte differentiation for 7 days in the presence or absence of HNE and then analyzed for the effect of HNE on adipogenic protein expression using western blot analysis. (A) PPARγ (B) C/EBPα (C) aP2 and (D) Glut4. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 7 day 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

Figure 13.

Effects of repeated HNE treatment on adiponectin and leptin levels of differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were induced for adipocyte differentiation for 7 days in the presence or absence of HNE and then cell medium from day 7 adipocytes was analyzed for the effect of HNE on adiponectin and leptin levels using ELISA (A) Adiponectin (B) Leptin. Results represent the means of five sets (n=5) of independent experiments conducted under identical experimental conditions. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated 7 day 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which was taken as percentage control in the represented graphs.

Figure 14.

Effects of repeated HNE treatment on free fatty acid levels of differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Levels of free fatty acids (FFA) in the culture medium of day 7 adipocytes following chronic HNE treatment were measured as described in methods. *P≤0.05 compared with untreated cells.

Repeated HNE treatment increases protein oxidation in differentiating adipocytes

Repeated HNE treatment on differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes resulted in a low level transient increase in oxidized, and HNE modified proteins, in day 7 adipocytes (Figure 15). This data is consistent with chronic HNE exposure promoting a sustained increase in oxidative stress within differentiating adipocytes.

Discussion

This study is the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate that HNE induces oxidative stress and alters multiple aspects of adipose biology, in both mature and differentiating adipocytes. These in vitro studies strongly support a role for HNE in regulating adipose tissue function and differentiation. Increases in oxidized proteins and HNE modified proteins are increasingly linked to adipose function during a variety of conditions including aging and obesity [43–44]. Based on our in vitro experiments with HNE, the acute and chronic presence of HNE may directly contribute to increased oxidative stress, impair adipogenesis, and alter multiple aspects of adipose function during each of these conditions.

Given the readily available lipid, and presence of numerous stressors capable of increasing ROS levels (hypoxia, inflammation, etc.), it is likely that sustained and rapid elevations in HNE levels can occur in adipose tissue. In the current study, we have demonstrated that acute HNE treatment is sufficient to increase ROS levels in mature adipocytes in a dose dependent manner, which is associated with decrease in lipid content. The loss of lipid content was associated with an increase in lipase expression, consistent with increased fatty acid release. These studies lay the framework for a model in which feed forward cascades of HNE and ROS generation occur within adipose tissue, and thereby modulate adipose tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, these data raise the potential for HNE effects on adipocytes contributing to regulation of circulating free fatty acids, and potentially to metabolic imbalance. Our study demonstrates that chronic treatment of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with physiological concentrations of HNE significantly impairs the adipogenesis and lipid accumulation. Our studies are consistent with the work in other laboratories which have demonstrated the ability of different oxidative stressors to inhibit the 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation [41]. Interestingly, our analysis showed that relatively low levels and physiological levels of HNE (< 10μM) were sufficient to impair the adipogenic potential of preadipocytes [19, 26–29]. Because of the importance of preadipocytes to the maintenance of adipose homeostasis, it is likely that the prolonged down regulation of adipocyte differentiation by HNE could have significant and negative effects on adipose health. In the present study, we observed a decrease in adipogenic protein expression including PPARγ, C/EBPα and aP2 following chronic HNE treatment. These alternations likely to contribute to down regulation of proteins involved in fatty acid uptake, synthesis and storage [4, 45–46]. Taken together, these data identify multiple lines of evidence for HNE effects on adipose biology contributing to metabolic complications relevant to metabolic syndrome.

The differential effect of acute and chronic HNE exposure on adipogeneic gene and protein expression, in mature and differentiating adipocytes is likely due to the differential susceptibility of these states of cell differentiation to HNE induced oxidative stress. Studies are currently underway to clarify this issue. Cells have various defense mechanisms to maintain the homeostasis in response to oxidative stress. In normal conditions excessive ROS produced is removed by intracellular anti redox systems. Previous reports suggest that HNE induced oxidative stress and its deleterious effects on insulin signaling could be reversed by the increased expression of HNE metabolizing enzymes such as fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase (FALDH) [26] indicating their potential role detoxification of aldehydes. An imbalance in antioxidant and redox status that is observed with aging and metabolic syndrome could lead to excessive ROS levels and increased oxidative stress that results in impaired adipocyte differentiation. The loss of preadipocytes (impaired differentiation) would be expected to disrupt adipose homeostasis and overall metabolism in multiple ways. For example, fewer preadipocytes will increase the ratio of mature adipocytes within adipose tissue. This shift in more aged cells results in having more cells within the tissue that are more vulnerable to insulin resistance, likely less able to promote beneficial adipokine secretion, as well as increase the number of cells more capable of elevating circulating levels of lipid. Interestingly, these results are consistent with the recent studies in mice that demonstrated an altered replication and differentiation of preadipocytes and an association between reduced fat mass with increased oxidative stress and age [47–49].

Increased ROS production following HNE treatment may prevent further lipid storage, increasing the levels of free fatty acids, but may also simultaneously cause dysregulated expression of adipocytokines, such as adiponectin as observed in our studies and with others in case of metabolic syndrome [4,50]. It is possible that oxidative stress induced decrease in lipid content in mature adipocytes could increase the FFA levels which could redistribute to ectopic sites other than adipose tissue. Because the impaired adipogenesis and ectopic lipid accumulation are closely related to insulin resistance [41,51] a deterioration of adipose tissue function is likely to contribute to impaired glucose homeostasis. Inhibition of adipogenesis may also lead to FFA elevation in treated cells with the increase in oxidative stress. Studies suggest that increased release of FFA from adipose tissue is a risk factor for FFA elevation in the circulation that contributes to systemic insulin resistance in obesity [52,53] and elevation of plasma FFAs are linked to increased lipolysis in conditions such as obesity [40].

Our studies support a model whereby physiological levels of HNE, formed by low level oxidative stress, promote a feed forward cascade of altered adipose homeostasis and oxidative stress. The effects of HNE are significant towards adipogenesis and mature adipocyte biology, indicating a role for HNE in regulating multiple modalities of adipocyte and adipose biology, with each of these alterations likely contributing towards the development of metabolic disease in response to obesity and other conditions where the levels of HNE in adipose tissue can become elevated. Together, these data identify HNE as a potent and important mediator of oxidative stress pathophysiology in adipose tissue, and suggest HNE may be a potential target for therapeutic strategies which ameliorate adipose pathogenesis in the context of obesity.

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by the Hibernia National Bank/Edward G. Schleider Chair and grants from the NIA (AG029885 and AG025771) to J.N.K.

Abbreviations

- 4-HNE

4-Hydroxynonenal

- aP2

Adipocyte Protein 2

- C/EBPα

CAAT-enhancer-binding protein α

- DHE

Dihydroethidium

- DNPH

2, 4-Dinitrophenyl hydrazine

- FFA

Free Fatty acid

- HSL

Hormone sensitive lipase

- LPL

Lipoprotein lipase

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, Satoh S, Nakano R, Ishii C, Sugiyama T, Eto K, Tsubamoto Y, Okuno A, Murakami K, Sekihara H, Hasegawa G, Naito M, Toyoshima Y, Tanaka S, Shiota K, Kitamura T, Fujita T, Ezaki O, Aizawa S, Kadowaki T, et al. PPAR gamma mediates highfat diet induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999;4:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mlinar B, Marc J. Review: New insights into adipose tissue dysfunction in insulin resistance. J Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011 doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.697. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:289–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1161. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakazono K, Watanabe N, Matsuno K, Sasaki J, Sato T, Inoue M. Does superoxide underlie the pathogenesis of hypertension? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10045–10048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohara Y, Peterson TE, Harrison DG. Hypercholesterolemia increases endothelial superoxide anion production. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2546–2551. doi: 10.1172/JCI116491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maddux BA, See W, Lawrence JC, Jr, Goldfine AL, Goldfine ID, Evans JL. Protection against oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance in rat L6 muscle cells by micromolar concentrations of α-lipoic acid. Diabetes. 2001;50:404–410. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudich A, Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Hemi R, Kanety H, Bashan N. Prolonged oxidative stress impairs insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1562–1569. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.10.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata M, Hakuno F, Yamanaka D, Okajima H, Fukushima T, Hasegawa T, Ogata T, Toyoshima Y, Chida K, Kimura K, Sakoda H, Takenaka A, Asano T, Takahashi S. Paraquat-induced oxidative stress represses phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activities leading to impaired glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20915–10925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimsrud PA, Picklo MJ, Sr, Griffin TJ, Bernlohr DA. Carbonylation of adipose proteins in obesity and insulin resistance: identification of adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein as a cellular target of 4- hydroxynonenal. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:624–637. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600120-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benedetti A, Pompella A, Fulceri R, Romani A, Comporti M. Detection of 4-hydroxynonenal and other lipid peroxidation products in the liver of bromobenzene-poisoned mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;876:658–666. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Codreanu SG, Zhang B, Sobecki SM, Billheimer DD, Liebler DC. Global analysis of protein damage by the lipid electrophile 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:670–680. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800070-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattson MP. Roles of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in obesity the metabolic syndrome and associated vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen DR, Doorn JA. Reactions of 4-hydroxynonenal with proteins and cellular targets. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji C, Amarnath V, Pietenpol JA, Marnett LJ. 4-hydroxynonenal induces apoptosis via caspase-3 activation and cytochrome c release. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:1090–1096. doi: 10.1021/tx000186f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng JZ, Singhal SS, Saini M, Singhal J, Piper JT, Van Kuijk FJ, Zimniak P, Awasthi YC, Awasthi S. Effects of mGST A4 transfection on 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated apoptosis and differentiation of K562 human erythroleukemia cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;372:29–36. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreuzer T, Grube R, Wutte A, Zarkovic N, Schaur RJ. 4-Hydroxynonenal modifies the effects of serum growth factors on the expression of the c-fos proto-oncogene and the proliferation of HeLa carcinoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:42– 49. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarkovic N, Ilic Z, Jurin M, Schaur RJ, Puhl H, Esterbauer H. Stimulation of HeLa cell growth by physiological concentrations of 4-hydroxynonenal. Cell Biochem Funct. 1993;11:279–286. doi: 10.1002/cbf.290110409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrera G, Pizzimenti S, Dianzani MU. Lipid peroxidation: control of cell proliferation cell differentiation and cell death. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dwivedi S, Sharma A, Patrick B, Sharma R, Awasthi YC. Role of 4-hydroxynonenal and its metabolites in signaling. Redox Rep. 2007;12:4–10. doi: 10.1179/135100007X162211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Echtay KS, Brand MD. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and uncoupling proteins: an approach for regulation of mitochondrial ROS production. Redox Rep. 2007;12:26–29. doi: 10.1179/135100007X162158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonarduzzi G, Robbesyn F, Poli G. Signaling kinases modulated by 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radical Biol Med. 2004;37:1694–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shearn CT, Smathers RL, Stewart BJ, Fritz KS, Galligan JJ, Hail N, Jr, Petersen DR. Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) inhibition by 4-hydroxynonenal leads to increased Akt activation in hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:941–952. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.069534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin InVest. 2003;112:1785– 1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demozay D, Mas JC, Rocchi S, Van Obberghen E. FALDH reverses the deleterious action of oxidative stress induced by lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal on insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1216–1226. doi: 10.2337/db07-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esterbauer H. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of lipid-oxidation products. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(5 Suppl):779S–785S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.779S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siems W, Grune T. Intracellular metabolism of 4-hydroxynonenal. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchida K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strohmaier H, Hinghofer-Szalkay H, Schaur RJ. Detection of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) as a physiological component in human plasma. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1995;11:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(94)00027-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syslova K, Kacer P, Kuzma M, Najmanova V, Fenclova Z, Vlckova S, Lebedova J, Pelclova D. Rapid and easy method for monitoring oxidative stress markers in body fluids of patients with asbestos or silica-induced lung diseases. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2477–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyokuni S, Yamada S, Kashima M, Ihara Y, Yamada Y, Tanaka T, Hiai H, Seino Y, Uchida K. Serum 4-hydroxy- 2-nonenal-modified albumin is elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Antioxid Redox Signaling. 2000;2:681–685. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shearn CT, Fritz KS, Reigan P, Petersen DR. Modification of Akt2 by 4-hydroxynonenal inhibits insulin-dependent Akt signaling in HepG2 cells. DR Biochemistry. 2011;50:3984–3996. doi: 10.1021/bi200029w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tirosh A, Potashnik R, Bashan N, Rudich A. Oxidative stress disrupts insulin-induced cellular redistribution of insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10595–10602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE. ACRP30/adiponectin: An adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen ED, Walkey CJ, Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1293–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsubara M, Maruoka S, Katayose S. Inverse relationship between plasma adiponectin and leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:173–180. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1470173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicklas BJ, Rogus EM, Colman EG, Goldberg AP. Visceral adiposity increased adipocyte lipolysis and metabolic dysfunction in obese postmenopausal women. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E72–78. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.1.E72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Findeisen HM, Pearson KJ, Gizard F, Zhao Y, Qing H, Jones KL, Cohn D, Heywood EB, de Cabo R, Bruemmer D. Oxidative stress accumulates in adipose tissue during aging and inhibits adipogenesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Z, Dou X, Gu D, Shen C, Yao T, Nguyen V, Braunschweig C, Song Z. 4-Hydroxynonenal differentially regulates adiponectin gene expression and secretion via activating PPARγ and accelerating ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;349:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Ebenezer PJ, Dasuri K, Fernandez-Kim SO, Francis J, Mariappan N, Gao Z, Ye J, Bruce-Keller AJ, Keller JN. Aging is associated with hypoxia and oxidative stress in adipose tissue: implications for adipose function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E599–607. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00059.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dasuri K, Zhang L, Ebenezer P, Fernandez-Kim SO, Bruce-Keller AJ, Szweda LI, Keller JN. Proteasome alterations during adipose differentiation and aging: links to impaired adipocyte differentiation and development of oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1727–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans RM, Barish GD, Wang YX. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye J. Emerging role of adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and insulin resistance. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:54–66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Djian P, Roncari AK, Hollenberg CH. Influence of anatomic site and age on the replication and differentiation of rat adipocyte precursors in culture. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1200–1208. doi: 10.1172/JCI111075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karagiannides I, Tchkonia T, Dobson DE, Steppan CM, Cummins P, Chan G, Salvatori K, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Kirkland JL. Altered expression of C/EBP family members results in decreased adipogenesis with aging. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R1772–1780. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.6.R1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirkland JL, Hollenberg CH, Gillon WS. Age anatomic site and the replication and differentiation of adipocyte precursors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1990;258:C206–210. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maury E, Brichard SM. Adipokine dysregulation adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;314:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scherer PE. Adipose tissue: from lipid storage compartment to endocrine organ. Diabetes. 2006;55:1537–1545. doi: 10.2337/db06-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boden G. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and NIDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delarue J, Magnan C. Free fatty acids and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:142–148. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328042ba90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]