Abstract

Background and objective

To evaluate frame registration and averaging algorithms for optical coherence tomography.

Patients and Methods

Normal and glaucoma eyes (n=20 each) were imaged. Objective differences were measured by comparing noise variance (NV), spread of edge (SE), and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR). Subjective image quality was also evaluated.

Results

Two frame-averaging algorithms (FA400 and FA407) had better NV and CNR, but worse SE than did single frames (p<0.01). Additionally, both algorithms provided better subjective assessments of structure boundaries than did single images (p<0.001). Algorithm FA407 had significantly lower SE and better ILM visualization than did FA400.

Conclusion

Frame-averaging significantly suppressed speckle noise and increased the visibility of retinal structures. However, imperfect image registration caused edge blurring that could be detected by the SE parameter. In frame-averaging algorithms, higher CNR and lower NV indicated better noise suppression, but SE was most sensitive in comparing edge preservation between algorithms.

INTRODUCTION

Several image enhancement techniques have been developed for suppressing speckle noise that can compromise the quality of optical coherence tomography (OCT) images. There are two basic approaches to these enhancement techniques: image frame averaging and image spatial filtering. Most OCT instruments used in ophthalmology have the frame-averaging function, including the Spectralis (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), Spectral OCT/SLO (OPKO/OTI, Miami, FL, USA), 3D OCT-2000 (Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and Cirrus HD-OCT (Carl Zeiss, Germany), etc.1 In this study, we have included only frame-averaging techniques for noise suppression. The averaging approach is a widely used, very effective, and important way of improving the signal-to-noise ratio in speckled noisy images.2 It combines multiple registered frames of the same region into a single image.3–5 Depending on the accuracy of the image registration, the speckle noise could be reduced as much as n1/2, where n is the number of frames to be averaged.6 Though the frame-averaging method can improve image quality by suppressing background and speckle noises, at the same time, artifacts may be introduced if registration of the frames does not adequately remove motion error.

There are two frame-averaging techniques. The first one combines a scanning laser ophthalmoscope with OCT to produce tracking laser tomography. This enables real time tracking of eye movements and averaging of multiple B-scans.7, 8 This is the method used in the Spectralis OCT instrument. The other one is a post-processing method, in which the frame averaging is based on image registration after scan acquisition9 as done by the RTVue Fourier domain-OCT instrument (Optovue, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) and the Cirrus HD-OCT instrument (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA). In this paper, we focus on the evaluation of image registration after scan acquisition as accomplished by the RTVue.

Image quality is not associated with a single factor, but rather it is a composite of a variety of factors. We evaluated three factors, noise, blurring, and contrast, for their contribution to OCT image quality. We then determined if averaging OCT images improved image quality by suppressing background and speckle noise.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol wase approved by the institutional review boards of university of southern California. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Twenty normal and twenty glaucoma patients were randomly selected from the University of Southern California center of the Advance Imaging for Glaucoma Study (AIGS) [www.aigstudy.net]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of normal and glaucomatous eyes have been described previously by our group10 or been found in the manual of procedure of AIGS (www.aigstudy.net). Only one eye was randomly selected for each patient.

Image acquisition

To evaluate the performance of the frame-averaging algorithm, a Fourier domain OCT system (RTVue) was used to acquire images from 6-mm line scans centered at the fovea. Image resolution was 5 μm axially and 20 μm transversally. Sixteen consecutive frames were acquired at the same retinal position for each line scan. Each frame consisted of a B-scan combined with 1024 A-scans. Two different versions of RTVue software, version 4.0.0.143 (algorithm FA400) and the updated version 4.0.7.4 (algorithm FA407), were used for registering and averaging the consecutive frames for each line scan (Fig. 1). As frames may lose similarity due to big eye movement, only frames with good similarity were averaged. Thus the actual number of frames used for averaging was case dependent.

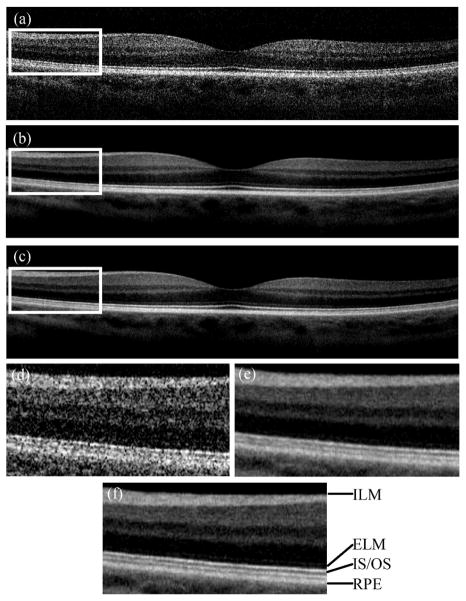

Figure 1.

OCT images of a single frame and averaged frames. (a) Single frame. (b) Frame averaged by Algorithm FA400. (c) Frame averaged by Algorithm FA407. (d – f) Corresponding regions in the white square of (a – c) respectively. ILM, internal limiting membrane; IS/OS, inner–outer segments; ELM, external limiting membrane; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Objective assessment parameters

We used three image parameters for objective assessment: (1) Noise variance (NV) evaluated noise suppression11 and was used to evaluate the speckle noise intensity. Less speckling meant that more details of retinal structure could be observed. (2) Spread of edges (SE) evaluated edge blurring due to misregistration.12 Less blurring meant that the junctions between each layer in retina could be differentiated more easily. (3) Contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) assessed contrast enhancement.13, 14 High CNR meant that more details from the hyperreflective layers (e.g., retinal never fiber layer) to the hyporeflective layers (e.g., photoreceptor layer) could be seen clearly.

Image noise is recognized as a fundamental component of image quality for all imaging modalities.15 It depends on many parameters of the image, such as image texture, average luminance of the image, bandwidth of noise, and noise standard deviation (SD).16–18 Kayargadde showed that image noise depends mainly on the noise SD, and the most reliable method for noise SD estimation is based on average local variance.19 Especially in OCT, speckle noise is a coherent phenomenon that causes variations in signal strength within a coherent length. This causes an increase in the high spatial frequency component of the image. Thus we evaluated noise by assessing the high frequency component using noise variance. The average local variance represents the noise SD of a pixel. It can be calculated as the average variance of a small region that includes the pixel itself and the 8 nearest neighbor pixels. For that reason, we used a fast NV estimation method to evaluate noise in the OCT images.11 This algorithm uses a zero mean operator N, which is almost insensitive to the image structure.

| (1) |

The NV in image I can be computed as

| (2) |

where W and H are width and height of the image respectively; x and y is the coordinate of each pixel in the image; * means convolution. The variance of the output from the convolution between operator N and I(x, y) is an estimate of the noise variance that belongs to a pixel located in coordinate (x, y) in the whole image. A small value of σn means less noise corruption and more detail of visible structures. However, blurring suppresses high frequency tissue boundaries and also leads to lower NV.

Misregistration of frame-averaging algorithms can blur the image while reducing speckle noise. Blurring tends to blend each image point with the surrounding area. This smears the edges and induces a loss of general detail. Marziliano’s blur metric correlates well with the perception of blur and has a very low complexity.12 We used this objective algorithm to measure SE, the blur measurement for edge location. To achieve this, a Sobel edge detector20 was applied to calculate the edge of the object. In simple terms, an image gradient is a change in intensity of the image. An edge occurs when the gradient is greatest in the local image. A Sobel edge detector uses this fact to find edges. It calculates the gradient of the image intensity at each point by convolving the image with a pair of 3×3 filters. The largest possible direction that increases from light to dark and the rate of change in this direction can be determined. The result shows whether or not this point represents an edge. Then noise was removed by applying a threshold to the gradient image. Pixels corresponding to the edge location were then found by scanning each row of the processed image. According to the locations of the local luminance extrema closest to the edge, the start and end positions of the edge were defined. Finally, the local SE was determined by calculating the distance between the start and end positions, which could be regarded as the “thickness” of edge. The retina consists of many layers that are generally lying in the depth direction of OCT images. Here we used the global blur measurement for the evaluation. This was obtained by averaging local blur values over the whole upper edge of the retina. Thus, only the depth direction was measured because of the characteristics of the retinal structures in the OCT images. Small values of SE meant less blur, and the edge of each layer was more discernible.

The detectability of an object is largely determined by the signal difference with neighboring objects or background and can be described by the CNR.13 High contrast allows humans to easily differentiate between regions and detect edges and slight changes in luminance. Thus the CNR can serve as a quantitative and intuitive parameter to evaluate the performance and quality of images.14 It is defined as,

| (3) |

where f is the mean signal intensity of the retina in the image (foreground), b is the mean signal intensity of the surrounding region (background), and δf and δb are the corresponding standard deviations. Larger values of CNR meant that the image has better contrast.13, 21 The CNR is proportional with image enhancement method performance. A higher CNR meant that more detailed information of the retina was clear, even those structures with low luminance features.

Subjective assessment parameters

Subjective grading of the internal limiting membrane (ILM), inner–outer segments junction (IS/OS), external limiting membrane (ELM), and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) was also used for image quality assessment. The layers were defined in figure 1f. The grader provided his perception of quality for each structure based on a scoring system. For each of these structures, the quality of the images was assessed on a four level grading scale: Poor, 1; Fair, 2; Good, 3; and Excellent, 4. (table 1)

TABLE 1.

Grading scale for subjective assessment

| ILM | IS/OS | ELM | RPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | very clear | very clear | 100% | 90% – 100% |

| Good | clear | clear | 75% – 99% | 70% – 89% |

| Fair | slightly blurry | slightly blurry | 50% – 75% | 50% – 69% |

| Poor | blurry | blurry | 0% – 50% | 0% – 50% |

ILM, sharpness of inner limiting membrane; IS/OS, sharpness of inner segment/outer segment junction; ELM, continuity of external limiting membrane; RPE, double layer feature in retinal pigment epithelium

For ILM and I/OS, the grader checked the edge sharpness, or how blurry the edge is. The two edges were the sharpest edges in OCT images of the retina. They would become blurry if the registration did not correct the eye movement sufficiently. Thus the edge sharpness can be used to qualitatively assess the registration accuracy of the frame-averaging procedure.

For ELM and IS/OS, the grader checked the continuity of the ELM and visibility of the double-layer feature in RPE band. The reflectance of ELM was just slightly higher than its neighbor layers. On the contrary, the two bright bands in RPE were close and the gap between the two bands is just slightly darker than them. Thus these two features were sensitive to the noise level of the image and can be used to measure the image enhancement.

Evaluation process

To better compare single frames and averaged frames, each image used for evaluation was divided into 5 blocks (Fig. 2). The first, third, and fifth blocks were considered as the temporal, center, and nasal regions of retina. Finally a total of 360 block images, including raw single frame images and both kinds of frame-averaged images, were used in the assessment.

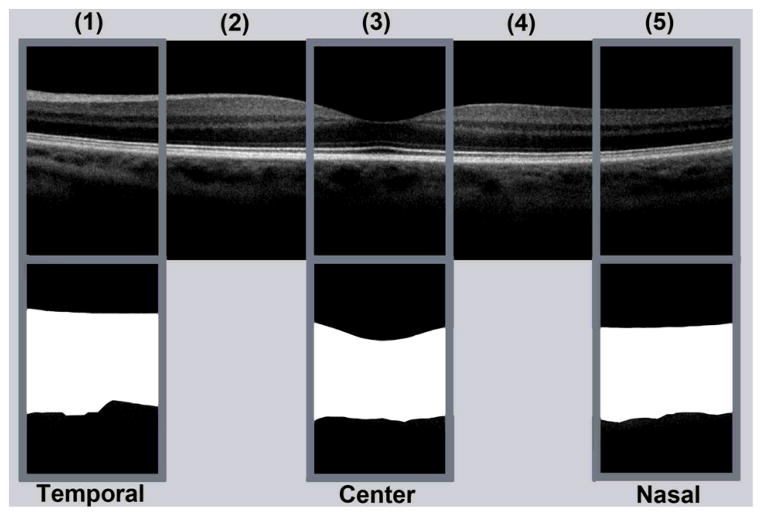

Figure 2.

Five blocks of a retina OCT image. The 1st, 3rd and 5th blocks were used for assessment. These three regions were segmented into retina/foreground (white) and background (black) for contrast-to-noise ratio.

Three objective assessment parameters were calculated respectively based on these three regions. To calculate the CNR of the tested regions, a segmentation algorithm was used to divide each region into retina and background (Fig. 2).

For subjective assessment parameters, one block of OCT image was displayed on the computer screen without any boundary line overlaid on it and the ophthalmologist was asked to provide his perception of the quality of this block according to the grading scale (Table 1). The images are displayed in gray color and the ophthalmologist is confident in locating these layers from the OCT image. All images were de-identified and displayed in a random order. The ophthalmologist could not proceed with the next image until the current image was graded, nor could he change the score of previous image.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test22 was used to evaluate the significance of differences in image quality. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Both the evaluation of objective assessment parameters and statistical analyses were performed using Matlab 7.0 (Mathworks, Natick, MA). All of the subjective grading was made by co-author RRP, who was a retinal specialist in the Doheny Image Reading Center during this study.

RESULTS

Forty scans from 20 normal subjects and 20 glaucoma subjects were graded. The age of normal group is 63.5±9.2 years and the age of glaucoma group is 63.4±11.9 years. Females comprised 80% of the normal group and 50% of the glaucoma group. The mean deviation (MD) of normal group is 0.16±1.08 dB, and pattern standard deviation (PSD) is 1.55±0.23 dB. The in the glaucoma group, MD is −4.27±5.10 dB and PSD is 5.16±4.42 dB.

For the FA400 algorithm, 9.75±3.85 frames out of 16 frames were averaged for normal eyes and 8.35±3.66 frames out of 16 frames were averaged for glaucoma eyes. For FA407, 8.75±3.91 frames and 7.80±3.56 frames out of 16 frames were averaged for normal and glaucoma eyes respectively. The difference between the two versions and the two populations were not significant (p>0.05). Due to the similarity of the results from normal and glaucoma groups, we combined the data for the normal and glaucoma eyes together for the analysis of objective and subjective assessments.

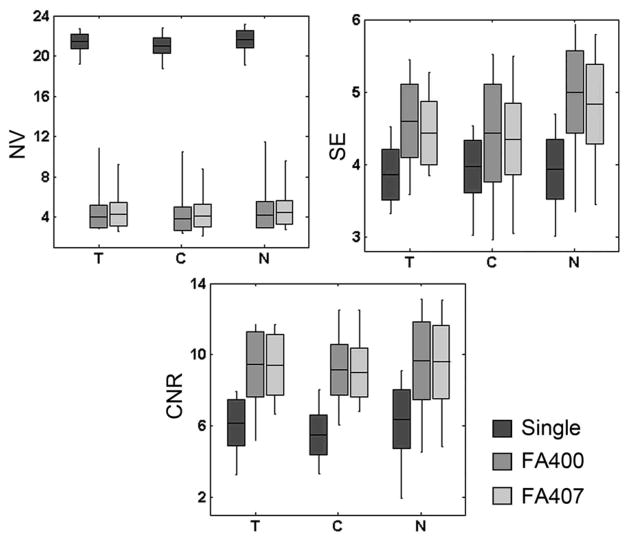

Based on objective assessments of NV, the FA400 and FA407 frame-averaged values were lower than the single frame values (p<0.001, Fig. 3). For SE and CNR, both frame-averaged objective assessments were greater than the single frame values (p<0.001, Fig. 3). For NV and CNR, there were no significant differences between the FA400 and FA407 frame averaging for the combined temporal, central, and nasal retinal data (Table 2). However, the NV calculated from the central part of retina with FA400 was significantly lower than FA407 (p=0.02). Furthermore, for SE, FA407 was significantly better than FA400 (p=0.04). Both frame-averaging algorithms of the combined retinal regions provided better objective assessments of NV, SE, and CNR than did single images (p<0.001, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Single- and frame-averaged values of objective assessments at the temporal (T), center (C) and nasal (N) regions. Comparing FA400 and FA407 frame-averaging results to single images, all p<0.001. Black line in the center of each box, mean value; upper and lower borders of box, variance values; lines extending from ends of box, minimum and maximum values.

TABLE 2.

Average value of objective assessment

| Images | NVa | SEa | CNRa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 21.4±0.73 | 3.92±0.28 | 6.01±1.17 |

| FA400 | 4.03±1.18 | 4.68±0.37 | 9.41±1.58 |

| FA407 | 4.27±1.13 | 4.54±0.34 | 9.34±1.47 |

Data are means ± standard deviations based on values averaged from the temporal, center and nasal parts in retina, including normal and glaucoma eyes.

NV, noise variance; SE, spread of edges; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio.

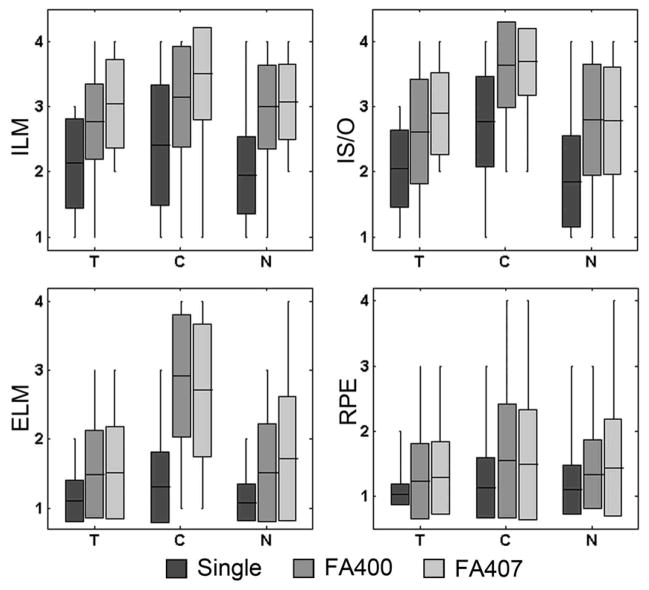

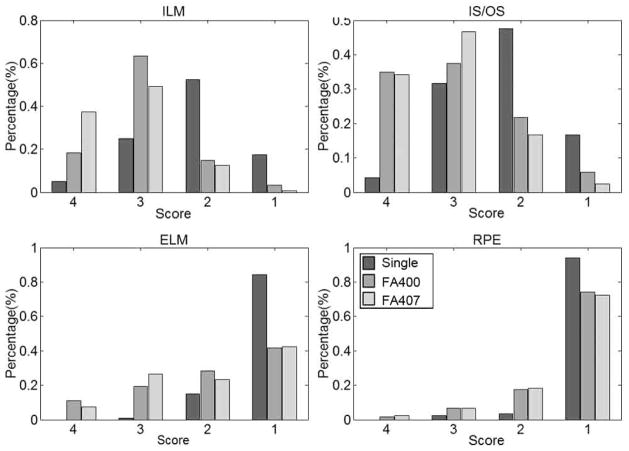

Both frame-averaging algorithms of the combined retinal regions gave better subjective assessments of ILM, IS/OS, ELM, and RPE than did single images (p<0.001, Table 3, Fig. 4). The grades for ILM value of FA407 algorithm was significantly better than the value of FA400 algorithm for the combined temporal, central, and nasal retinal data (p=0.01, Table 3). However, for IS/OS, ELM, and RPE, there were no significant differences between FA400 and FA407 frame averaging (p<0.001, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Average value of subjective assessment parameters

| images | ILMa | IS/OSa | ELMa | RPEa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 2.18±0.77 | 2.23±0.78 | 1.17±0.40 | 1.08±0.36 |

| FA400 | 2.97±0.69 | 3.02±0.90 | 1.99±1.02 | 1.36±0.68 |

| FA407 | 3.23±0.69 | 3.13±0.77 | 1.99±1.00 | 1.39±0.73 |

Data are means ± standard deviations based on values averaged from the temporal, center and nasal parts in retina, including normal and glaucoma eyes

ILM, inner limiting membrane; IS/OS, inner segment/outer segment; ELM, external limiting membrane; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium

Figure 4.

Single- and frame-averaged values of subjective assessments at temporal (T), center (C) and nasal (N) regions. ILM, internal limiting membrane; IS/OS, inner–outer segments; ELM, external limiting membrane; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium. Comparing FA400 and FA407 frame-averaging results to single images, all p<0.001.

All three objective assessment parameters had moderate (SE, r=0.37) to strong correlation (NV, r=0.51 and CNR, r=0.47) with subjective assessment of ILM edge sharpness (Table 4). The parameters NV and CNR also had strong correlation (r=0.42 each) with the subjective assessment for continuity of the ELM. The parameters NV and CNR had weak to moderate correlation with the subjective assessment for edge sharpness of IS/OS (r=0.31 and r=0.24 respectively) and visibility of the double-layered RPE (r=0.20 and r=0.24 respectively).

TABLE 4.

Correlation between subjective assessment parameters and objective assessment parameters

| Objective Parameters | Subjective Parameters

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILMa, | IS/OSa | ELMa | RPEa | |

| NV | 0.51 (<0.001) | 0.31 (<0.001) | 0.42 (<0.001) | 0.20 (<0.001) |

| SE | 0.37 (<0.001) | 0.12 (0.019) | 0.10 (0.057) | 0.10 (0.084) |

| CNR | 0.47 (<0.001) | 0.24 (<0.001) | 0.42 (<0.001) | 0.24 (<0.001) |

Person Correlation coefficient r and (p-values);

NV, noise variance; SE, spread of edges; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; ILM, internal limiting membrane; IS/OS, inner–outer segments; ELM, external limiting membrane; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

In both frame-averaging algorithms, less than 34.2% of the averaged images got good scores of 4 or 3 points for continuity of the ELM, and less than 9.2% of the averaged images for double layer visibility of the RPE got good scores (Fig. 5). On the contrary, more than 81.7% and 55.8% of the averaged images for the edge sharpness of the ILM and the IS/OS could got good scores.

Figure 5.

Score statistics for subjective assessment.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated by both objective and subjective measures that frame averaging significantly improves the quality of OCT images. Lower speckle noise level can induce smaller values of NV, while higher CNR can improve differences in the distinction between areas of interest. Averaged frames had smaller values of NV than single frames in the temporal, center, and nasal retinal locations. Thus frame averaging is useful for speckle noise suppression in OCT images. Simultaneously, CNR values increased in each region after frame averaging. This result is consistent with the subjective assessment for contrast improvement by Jørgensen and Sander.23 The objective results and subjective assessment indicated that the visualization of retinal structural details was increased in frame-averaged OCT images. This may improve the accuracy of retinal boundary detection and intra-retinal layer segmentation.

Compared with single frames, both frame-averaging algorithms got higher grades for all subjective assessments. For continuity of the ELM and visibility of the RPE, the differences between averaged frames and single frames were significant for both algorithms. Thus, frame averaging enabled recovery of detailed structural information in the retina. These subjective grades agreed with the objective assessments of CNR and NV.

Smaller SE values mean that the image is less blurred. The SE value of the single frames was significant smaller than the two frame-averaging algorithms. This indicates that the frame-averaged images were objectively more blurry than single-framed images. The blurring may be caused by the misregistration that can occur in frame averaging or out-of-frame motion. Subjective grades for the frame-averaged sharpness of the ILM and IS/OS in each region of the retinal image were significantly better than for single frames. Thus the contrast is more important than a small amount of edge blurring for subjective sharpness. The reason for this is that blurring caused by misregistration during frame averaging is very small. It may be just below the detectable blur threshold in human visual perception.24 At the same time, improved contrast in frame-averaged images can raise the threshold. Thus, subjective grades of the ILM and IS/OS show that edges in frame-averaged images are sharper than in single frames,25 though averaging introduces blurring.

Comparing these two frame-averaging algorithms, FA407 provided better visualization than FA400 of thin tissue boundaries such as the ILM. Presumably this was due to better image registration and less SE. FA407 also had slightly higher NV than FA400 due to better edge preservation, giving FA407 greater high spatial frequency content in the image. Thus higher NV actually was associated with better image registration. Overall, the SE was the objective factor that best discriminated the qualities of the registration algorithms, and the ILM was the image feature that was most sensitive to registration. The fact that the SE was significantly worse for both algorithms compared to single frame images indicated that there was significant misregistration of images with both algorithms. Further improvement may be possible using real-time tracking or improved registration in post-processing.

Both objective and subjective results revealed that frame-averaging algorithms suppress speckle noise and increase the useful signal. As the Pearson linear correlation between these two assessment parameters showed, when the p-value was less than 0.05, the correlation R2 was significantly different from zero. The correlation results indicate that NV and CNR are important in the subjective perception of all retinal layers graded. With higher values of CNR and lower NV, more structural details can be observed in OCT images.

Image diagnostics and quantization of pathologies in the clinical setting are facilitated by contrast enhancement in frame-averaged OCT images. The small blurring induced by misregistration is just under the detectable blur threshold of human perception, and it does not influence the clinical use of frame-averaged OCT images. However, according to the score statistics for subjective assessment, even though existing frame-averaging algorithms significantly enhanced OCT image quality, improvements are necessary for consistent detection of small features. As suggested above, using eye-tracked frame averaging or a better registration algorithm may lead to better results.

In conclusion, frame averaging significantly suppresses speckle noise and increases the visibility of retinal structures, but it blurs boundaries. Edge blurring indicates misregistration or out-of-frame motion. In the two frame registration algorithms compared in this study, FA407 preserved the sharpness of edges better than FA400 and had better subjective grading. Frame-averaging methods could be further improved by either better registration or transverse retinal tracking. Finally, to evaluate frame-averaging algorithms, higher CNR and lower NV indicate better noise suppression, but SE is most sensitive in comparing edge preservation between algorithms.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This study was supported by the NIH grant R01 EY013516, the State Scholarship Fund of China 2009632110.

Footnotes

OCIS codes: 170.4470, 170.4500, 170.3890, 110.4280.

Presented in part as a research poster at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, May 1–5, 2010, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

Statement:

Financial and proprietary interest:

Wei Wu, Rajeev R. Pappuru, and Huilong Duan have no financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned. Ou Tan and David Huang received grant support from Optovue Inc.; David Huang received travel support from Optovue, Inc. David Huang received patent royalty, speaker honorarium, and stock options from Optovue, Inc.

References

- 1.Alonso-Caneiro D, Read SA, Collins MJ. Speckle reduction in optical coherence tomography imaging by affine-motion image registration. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2011;16:116027. doi: 10.1117/1.3652713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadjadi AF. Perspective on techniques for enhancing speckled imagery. Optical Engineering. 1990;29:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam D, Beilin-Nissan S, Friedman Z, Behar V. The combined effect of spatial compounding and nonlinear filtering on the speckle reduction in ultrasound images. Ultrasonics. 2006;44:166–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trahey EGW, Smith S, Ramm OTV. Speckle pattern correlation with lateral aperture translation: Experimental results and implications for spatial compounding. IEEE Trans Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 1986;33:257–264. doi: 10.1109/t-uffc.1986.26827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burckhardt CB. Speckle in ultrasound b-mode scans. IEEE Trans Sonics and Ultrasonics. 1978;25:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behar V, Adam D, Friedman Z. A new method of spatial compounding imaging. Ultrasonics. 2003;41:377–384. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(03)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiernan DF, Mieler WF, Hariprasad SM. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: A comparison of modern high-resolution retinal imaging systems. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 149:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hangai M, Yamamoto M, Sakamoto A, Yoshimura N. Ultrahigh-resolution versus speckle noise-reduction in spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Optics Express. 2009;17:4221–4235. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.004221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Velthoven MEJ, Faber DJ, Verbraak FD, van Leeuwen TG, de Smet MD. Recent developments in optical coherence tomography for imaging the retina. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2007;26:57–77. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan O, Chopra V, Lu ATH, et al. Detection of macular ganglion cell loss in glaucoma by Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2305–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Immerkaer J. Fast noise variance estimation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding. 1996;64:300–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marziliano P, Dufaux F, Winkler S, Ebrahimi T. Perceptual blur and ringing metrics: Application to jpeg2000. Signal Processing: Image Communication. 2002;19:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogowska J, Brezinski ME. Evaluation of the adaptive speckle suppression filter for coronary optical coherence tomography imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2000;19:1261–1266. doi: 10.1109/42.897820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geissler A, Gartus A, Foki T, Tahamtan AR, Beisteiner R, Barth M. Contrast-to-noise ratio (cnr) as a quality parameter in fmri. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;25:1263–1270. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tapiovaara MJ, Wagner RF. Snr and noise measurements for medical imaging - i a practical approach based on statistical decision-theory. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 1993;38:71–92. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/38/1/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barni M, Bartolini F, Piva A. Improved wavelet-based watermarking through pixel-wise masking. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 2001;10:783–791. doi: 10.1109/83.918570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis AS, Knowles G. Image compression using the 2-d wavelet transform. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 1992;1:244–250. doi: 10.1109/83.136601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kayargadde V, Martens J-B. An objective measure for perceived noise. Signal Processing. 1996;49:187–206. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitas I. Digital image processing algorithms and applications. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2000. p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Liu KJR, Lo S-CB. Fractal modeling and segmentation for the enhancement of microcalcifications in digital mammograms. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1997;16:785–798. doi: 10.1109/42.650875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiß P. Applications of generating functions in nonparametric tests. Mathematica Journal. 2005;9:803–823. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen TM, Sander B. Contrast enhancement of retinal b-scans from oct3/stratus by image registration - clinical applications. In: Manns F, Soederberg PG, Ho A, Stuck BE, Belkin M, editors. Ophthalmic technologies xvii. Vol. 6426. Bellingham: Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering; 2007. pp. 42608–42608. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogervorst MA, van Damme WJM. Visualizing the limits of low vision in detecting natural image features. Optometry and Vision Science. 2008;85:951–962. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181886fc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanz I, Calvo ML, Chevalier M, Lakshminarayanan V. Perception of high-contrast blurred edges. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation. 2001;12:240–254. [Google Scholar]