Abstract

Background

There is a growing mandate for Family Medicine residency programs to directly assess residents’ clinical competence in Care of the Elderly (COE). The objectives of this paper are to describe the development and implementation of incremental core competencies for Postgraduate Year (PGY)-I Integrated Geriatrics Family Medicine, PGY-II Geriatrics Rotation Family Medicine, and PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE for COE Diploma residents at a Canadian University.

Methods

Iterative expert panel process for the development of the core competencies, with a pre-defined process for implementation of the core competencies.

Results

Eighty-five core competencies were selected overall by the Working Group, with 57 core competencies selected for the PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents and an additional 28 selected for the PGY-III COE residents. The core competencies follow the CanMEDS Family Medicine roles. Both sets of core competencies are based on consensus.

Conclusions

Due to demographic changes, it is essential that Family Physicians have the required skills and knowledge to care for the frail elderly. The core competencies described were developed for PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents and PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE, with a focus on the development of geriatric expertise for those patients that would most benefit.

Keywords: core competencies, core competency development, core competency assessment, care of the elderly residents, family medicine residents, enhanced skills

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 50 years, the age of Canada’s population has changed dramatically, with the number of seniors increasing from 8% of the population in 1971 to 14.8% in 2012.(1,2) It is projected that this segment of the Canadian population will increase to 27.2% by 2056.(3) The increase in the number of seniors in the Canadian population has important implications for health-care delivery. One of those implications is the current transformation of health-care delivery from an approach focused on acute illness to one that recognizes the prevalence of chronic and complex disease.(4,5) As noted by MacAdam, “… integrated care for the elderly has become a major theme in health reform because of well-documented issues surrounding the poor quality of care being delivered to those with chronic conditions”.(6) It also has been noted that the strongest programs of integrated care include active involvement of physicians.(6) By 2020, family physicians can anticipate that at least 30% of their outpatients, 60% of their inpatients, and 95% of their continuing care patients will be aged 65 and older.(7,8)

In Canada, physicians who specialize in caring for the older adult include specialists in geriatric medicine, geriatric psychiatrists, and family physicians who have taken additional training in ‘Care of the Elderly’ (COE). In 2009, there were 228 geriatricians in Canada, but an estimated need for 500.(9) Significantly, 20% of Canadian geriatricians are nearing retirement age and few physicians are electing to train in this area.(10) In 2009, there were approximately 130 physicians who had completed COE training.(11) The United States is experiencing a similar geriatrician shortage.(11,12) All of these considerations underscore the importance of the need for, and the important role that, COE physicians play in the delivery of health services to seniors with complex health needs.

METHODS

Program

COE academic programs are sanctioned by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) and were officially established in Canada in 1989. These 15 programs represent “elective, supplementary training in care of the elderly for 6 or 12 month’s duration, available after the two-year core Family Medicine residency”.(13) Core program requirements include experience in geriatric inpatient, geriatric psychiatry, ambulatory, continuing care, and outreach settings, as well as regular time in a longitudinal clinic. There also is a formal research project requirement. A full description of the COE Diploma requirements are published in the Standards for Accreditation of Residency Training Programs.(14)

In order to provide the resident with the requisite medical knowledge, clinical assessment skills, and attitudes (communication, responsibility, respectfulness, ethical consideration) in this area, COE residents completing an Enhanced Skills Diploma need clearly defined educational objectives.(15) Clearly defined educational objectives also are central to COE diploma program administrators in that they can serve as a guide in the development and/or refinement of the curriculum for the Enhanced Skills program and can serve as the foundation for evaluation of residents completing the program.

Our impetus for the development of core competencies for the COE was two-fold: 1) our recognition of the growing mandate for Family Medicine residency programs to directly assess residents’ clinical competence, and 2) the potential to use the core competencies to demonstrate the added benefit of Enhanced Skills COE Diploma training.

From the beginning, it seemed fundamental that the core competencies should be built on the learning objectives that were previously developed for COE residency training in Canada.(15) Those learning objectives relate closely to a specific lesson, and provide residents with requisite medical knowledge and clinical assessment skills. The core competencies, on the other hand, are more general, and relate to skills, behaviours, and knowledge that should be gained through a course or series of courses. The core competencies also differ from learning objectives in that the core competencies explicitly define expected levels of overall competence for practice. As such, core competencies allow for competency-based assessment of postgraduate medical education learners, which is a significant model change from past assessment practices.(16) Specifically, this switch to competence-based assessment determines whether learners “do the right thing at the right time in the right way in complex situations, by using and integrating the right internal and external resources, in accordance to professional roles and responsibilities” (slide 10).(17) An added benefit of standardized core competencies is that they also can be used to standardize expected learning outcomes, and provide direction to curriculum developers and content experts in terms of instructional strategies, feedback on relevancy of context, and the determination of the most relevant and up-to-date medical content.

The objectives of this paper are to describe the development of incremental core competencies for Postgraduate Year-I and Year-II Integrated Geriatrics/Geriatrics Rotation (PGY-I/II) Family Medicine and PGY-III Enhanced Skills Care of the Elderly for COE Diploma residents and the implementation of these core competencies into our program.

Development of Core Competencies

The development of the core competencies for the PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents and PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE residents at the University of Alberta followed an iterative process. That process involved three primary steps.

-

Selection of committee members

A COE Core Competency Working Group was established using interested and experienced members of the University of Alberta’s COE Residency Program Committee. Members were selected based on roles at the local and national level (e.g., Program Director, Divisional Director, experience on national committees). Members of our working group had sat on the national Canadian Geriatric Society’s Core Competency Committee for medical students, the CFPC’s Health Care of the Elderly Committee that worked on Core Competencies at the PGYI/II Family Medicine resident level and/or on the current CFPC’s Working Group on Assessment of Competence in Care of the Elderly. A list of members, based on components of the COE Competency Working Group, is provided in Table 1.

-

Identification of potential core competencies

Potential core competencies were identified through a focused review of the pertinent literature using PubMed and MEDLINE, as well as a review of guidelines published by other national societies, such as the American Geriatrics Society and the Canadian Geriatrics Society.(4,18–25) The 20 core competencies for medical students, developed by the Medical Education Committee of the Canadian Geriatrics Society, were selected by the COE Core Competency Working Group as a baseline.(24) An additional seven competencies were received from the national Health Care of the Elderly (HCOE) Committee on Core Competencies at the PGY-I/II level for Family Medicine residents.(26) Each COE Core Competency Working Group member then worked on competencies in a number of domains, developing core competencies expected at the PGY-I/II Family Medicine and PGY-III COE level of training.

-

Selection of core competencies

The draft list of core competencies for the two groups (PGY-I/II Family Medicine and PGY-III COE) were then circulated to each individual member of the Working Group who was asked to independently review the core competencies and indicate those that were appropriate, and if appropriate, for which level (PGY-I/II/III). Individual members then anonymously submitted this information to the Chair of the Working Group. Consensus statements that all members of the Working Group agreed to as being appropriate were retained, and those that were inappropriate were discarded. Statements that did not reach consensus were identified and discussed formally with all members of the Working Group. Those statements were revised until there was consensus or discarded because there was lack of agreement.

TABLE 1.

Roles of the Care of the Elderly Core Competency Working Group

| Member/Roles | Degree/Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Divisional Director | MD, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

| Care of the Elderly Working Group 2002 that reported to the CFPC on standards for accreditation | |

| Family Medicine Coordinator 2007–11 | MBChB, Dip. COE, Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

| COE Program Director 2011 – present | |

| CFPC Working Group on Assessment of Competence in Care of the Elderly member | |

| COE Program Director 2005–2009 | MD, Dip. COE, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

| Health Care of the Elderly committee member | |

| COE Program Director 2009–2011 | MD, Dip. COE, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

| Health Care of the Elderly committee member | |

| Undergraduate Coordinator | MBBS, Dip. COE, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

| CGS committee member on Core Competencies in the care of the older persons for Canadian medical students | |

| Research Director | PhD, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta |

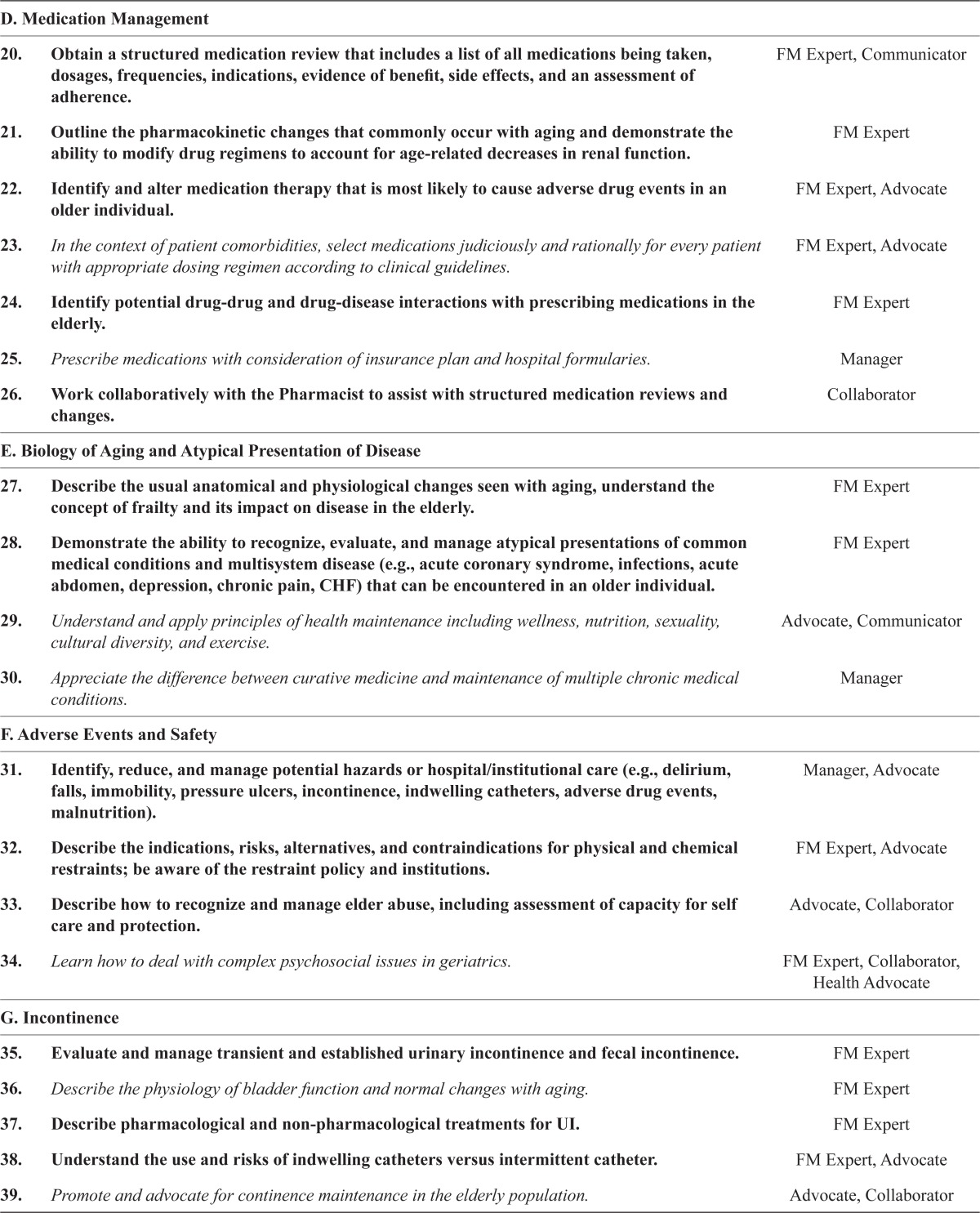

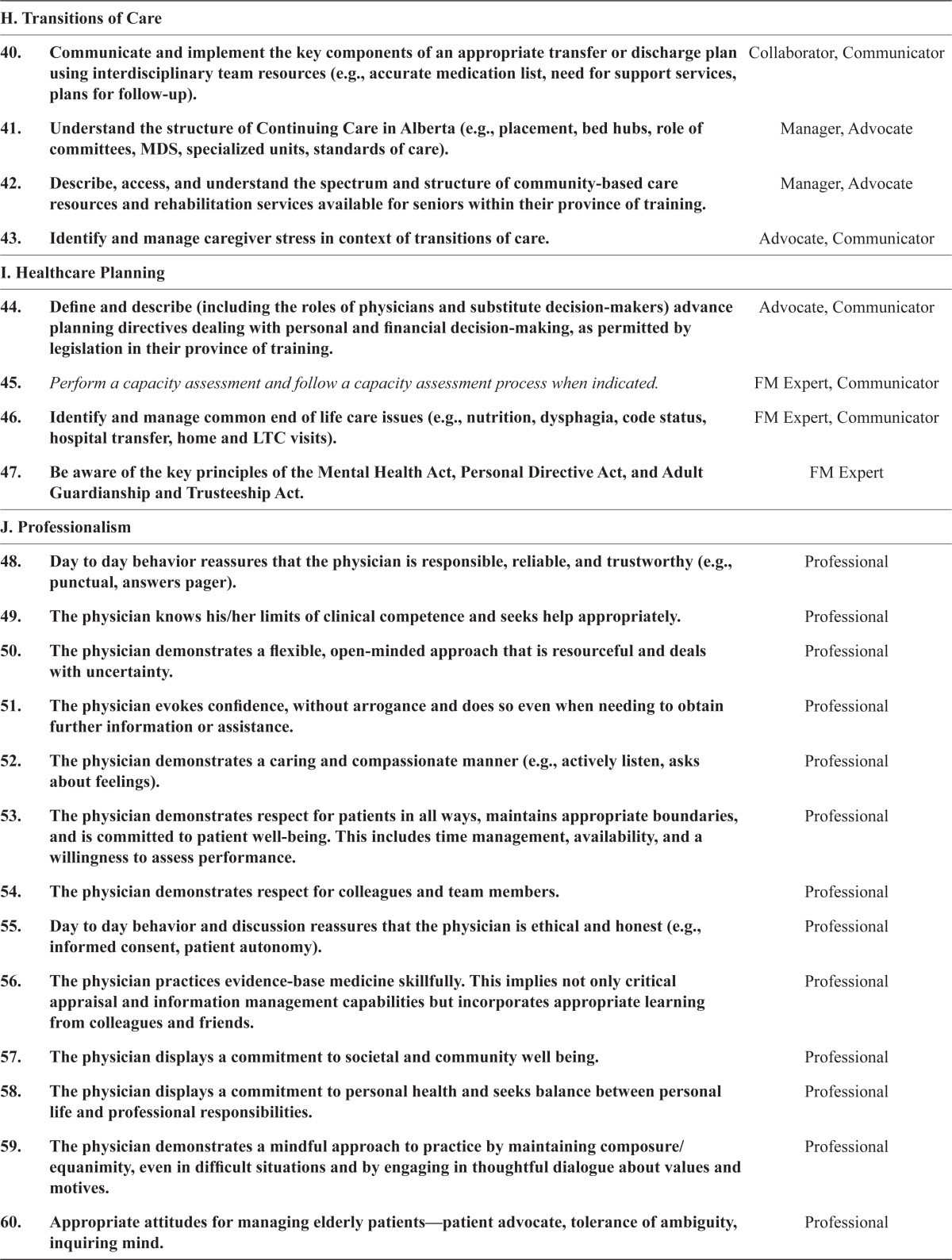

Fifty-seven core competencies were selected by the COE Core Competencies Working Group for the PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents, and an additional 28 (for a total of 85) core competencies were selected for the PGY-III COE residents (see Appendix A, Table A.1). Both sets of core competencies are consensus competencies that would be expected at the Family Medicine/COE level of training. They cover 12 primary domains which include cognition, function, mobility, medication, biology of aging, adverse events, incontinence, transitions of care, health-care planning, professionalism, communication, and research. Importantly, they follow the CanMEDS-Family Medicine Roles.(27) A description of CanMEDS-Family Medicine roles can be found in Appendix A, Table A.2.

Implementation of the Core Competencies

Implementation of the core competencies followed a pre-defined process, including methodologies to ensure opportunities to familiarize residents and preceptors with them before incorporating them into evaluation (rotation evaluations, exit examinations, etc.). The core competencies described above have been implemented into our program and serve as the foundation for the COE rotations at the University of Alberta. They also are utilized in the rotation evaluations/Academic Half-Day curriculum at the PGY-I/II/III resident level through clinical observation and Program Evaluation/Exit Examination at the PGY-III resident level. Each of these evaluations has been mapped to cover the respective core competencies.

DISCUSSION

The core competencies that were developed for PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents and PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE residents include behavioural competence, as well as performance competence, with a focus on enhancing learner performance and what we want them to achieve. They build on the competencies developed for medical students for better coordination of teaching and clinical experiences. They also define competence that would be expected of a Family Physician receiving integrated geriatrics or the more traditional geriatric’s rotation. Notably, a recent national survey of Family Medicine Residency education in Geriatric Medicine found that, between 2001 and 2004, the percentage of programs requiring geriatric clinical experience for all residents rose from 92% to 96%.(28) As such, core competencies are similarly important to Family Medicine residents who will increasingly be caring for older patients. An added advantage of having clearly defined competencies at the Family Medicine level is that they will help to ensure equivalent experiences for residents, irrespective of whether they are in an integrated or vertical one-month block.

Finally, the core competencies incrementally define the competence that would be expected of a Family Physician with Enhanced Skills in COE. There is much research outlining that geriatric expertise should be targeted to those patients who would most benefit (e.g., those aged 85 and older, or those who have complex medical problems, frailty or other geriatric conditions, disability, or dementia).(29–32) The consequences of not achieving these competencies are increased costs of care, poor coordination of services, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy.(5)

CONCLUSION

Due to demographic changes, the majority of health professionals today regularly care for elderly patients. It is thus crucial that Family Physicians and those with Enhanced Skills in COE have the required skills and knowledge to care for this segment of the population. Core competency requirements can be used to develop curriculum that will prepare future physicians to competently care for older people. The 57 core competencies for PGY-I/II Family Medicine residents are included as curriculum objectives on the University of Alberta Department of Family Medicine website and on the formal evaluation of their geriatrics rotation. The 85 core competencies were introduced into the PGY-III COE program in 2010 and overarch all components of the program. They define the rotation evaluations, the overall evaluation, Academic Half Day curriculum, and the Exit Examination. Currently we are researching the effects of these core competencies at the PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE level by retrospectively examining resident evaluations pre- and post-implementation of core competencies. Finally, it is hoped that the core competencies can be integrated into PGY-I/II geriatric rotations and PGY-III Enhanced Skills COE training nationally, with that work being done through the national HCOE Committee. One of the authors also sits on the CFPC Working Group on Assessment of Competence in Care of the Elderly. The experience gained in the development of the University of Alberta’s core competencies will be of benefit, and can be used to guide national efforts in this area.

APPENDICES

TABLE A.1.

PGY-I Integrated Geriatrics, PGY-II Geriatric Rotation, and PGY-III Core Competencies (with the 57 PGY-I/II core competencies bolded and the additional 28 PGY-III italicized)

| A. Cognitive Assessments | ||

|

| ||

| 1. | Perform a cognitive assessment and obtain collateral history relevant to cognitive and/or functional decline. | FM Expert, Communicator |

| 2. | Define and distinguish between the clinical presentations of delirium, dementia, and depression. | FM Expert |

| 3. | Diagnose delirium, formulate a differential diagnosis, and develop and implement plans for evaluation and management. | FM Expert |

| 4. | Diagnose common dementias, formulate a differential diagnosis, and develop plans for management. | FM Expert, Collaborator |

| 5. | Recognize and manage common issues in dementia care (e.g., driving, capacity, wandering, BPSD, rational use of antipsychotics, caregiver stress) during initial and follow-up visits. | FM Expert, Collaborator |

| 6. | Recognize and manage common psychogeriatric conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychosis, suicidality, somatization, substance use disorder). | FM Expert, Collaborator |

| 7. | Recognize the atypical forms of dementia (FTD, LBD, CJD) and develop plans for evaluation and management. | FM Expert, Collaborator |

| 8. | Utilize the Canadian Consensus Guidelines on Dementia to decide on assessment investigations. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 9. | Perform standard cognitive testing and have good knowledge and application of advanced cognitive testing relevant to the diagnosis of dementia and delirium. | FM Expert |

| 10. | Determine the appropriate use of medications to be used along the continuum of dementia (ACEI, psychotics, NMDA agonists). Recognize and identify their potential side effects, contraindications, and drug-drug and drug-disease interactions. | FM Expert |

| 11. | Generate appropriate referrals to relevant interdisciplinary team members and utilize their information in the management of delirium, dementia, and depression. | Collaborator, Manager |

|

| ||

| B. Functional Assessment (Self Care Capacity) | ||

|

| ||

| 12. | Evaluate baseline (pre-morbid) and current functional abilities (both basic and instrumental activities of daily living) using reliable sources of information including standardized assessment tools. | Collaborator, Communicator, FM Expert |

| 13. | Develop and implement plans for the assessment, management, and maintenance of patients with functional deficits, including the use of adaptive interventions, in collaboration with interdisciplinary team members. | Collaborator, Manager, FM Expert |

|

| ||

| C. Falls, Balance, and Gait Assessment | ||

|

| ||

| 14. | Construct a differential diagnosis (including risk factors) and plans for the evaluation, management, and prevention of falls. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 15. | Assess and manage gait, balance, and movement disorders using accepted standardized assessment tools. | FM Expert |

| 16. | Understand the causes of falls in the elderly (intrinsic and extrinsic). | FM Expert |

| 17. | Understand the impact and consequences of falls. | FM Expert |

| 18. | Identify consequences of immobility in the elderly patient. | FM Expert |

| 19. | Work with interdisciplinary teams to prevent, manage, and treat consequences of immobility in the elderly patient. | Collaborator, Manager |

|

| ||

| D. Medication Management | ||

|

| ||

| 20. | Obtain a structured medication review that includes a list of all medications being taken, dosages, frequencies, indications, evidence of benefit, side effects, and an assessment of adherence. | FM Expert, Communicator |

| 21. | Outline the pharmacokinetic changes that commonly occur with aging and demonstrate the ability to modify drug regimens to account for age-related decreases in renal function. | FM Expert |

| 22. | Identify and alter medication therapy that is most likely to cause adverse drug events in an older individual. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 23. | In the context of patient comorbidities, select medications judiciously and rationally for every patient with appropriate dosing regimen according to clinical guidelines. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 24. | Identify potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions with prescribing medications in the elderly. | FM Expert |

| 25. | Prescribe medications with consideration of insurance plan and hospital formularies. | Manager |

| 26. | Work collaboratively with the Pharmacist to assist with structured medication reviews and changes. | Collaborator |

|

| ||

| E. Biology of Aging and Atypical Presentation of Disease | ||

|

| ||

| 27. | Describe the usual anatomical and physiological changes seen with aging, understand the concept of frailty and its impact on disease in the elderly. | FM Expert |

| 28. | Demonstrate the ability to recognize, evaluate, and manage atypical presentations of common medical conditions and multisystem disease (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, infections, acute abdomen, depression, chronic pain, CHF) that can be encountered in an older individual. | FM Expert |

| 29. | Understand and apply principles of health maintenance including wellness, nutrition, sexuality, cultural diversity, and exercise. | Advocate, Communicator |

| 30. | Appreciate the difference between curative medicine and maintenance of multiple chronic medical conditions. | Manager |

|

| ||

| F. Adverse Events and Safety | ||

|

| ||

| 31. | Identify, reduce, and manage potential hazards or hospital/institutional care (e.g., delirium, falls, immobility, pressure ulcers, incontinence, indwelling catheters, adverse drug events, malnutrition). | Manager, Advocate |

| 32. | Describe the indications, risks, alternatives, and contraindications for physical and chemical restraints; be aware of the restraint policy and institutions. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 33. | Describe how to recognize and manage elder abuse, including assessment of capacity for self care and protection. | Advocate, Collaborator |

| 34. | Learn how to deal with complex psychosocial issues in geriatrics. | FM Expert, Collaborator, Health Advocate |

|

| ||

| G. Incontinence | ||

|

| ||

| 35. | Evaluate and manage transient and established urinary incontinence and fecal incontinence. | FM Expert |

| 36. | Describe the physiology of bladder function and normal changes with aging. | FM Expert |

| 37. | Describe pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for UI. | FM Expert |

| 38. | Understand the use and risks of indwelling catheters versus intermittent catheter. | FM Expert, Advocate |

| 39. | Promote and advocate for continence maintenance in the elderly population. | Advocate, Collaborator |

|

| ||

| H. Transitions of Care | ||

|

| ||

| 40. | Communicate and implement the key components of an appropriate transfer or discharge plan using interdisciplinary team resources (e.g., accurate medication list, need for support services, plans for follow-up). | Collaborator, Communicator |

| 41. | Understand the structure of Continuing Care in Alberta (e.g., placement, bed hubs, role of committees, MDS, specialized units, standards of care). | Manager, Advocate |

| 42. | Describe, access, and understand the spectrum and structure of community-based care resources and rehabilitation services available for seniors within their province of training. | Manager, Advocate |

| 43. | Identify and manage caregiver stress in context of transitions of care. | Advocate, Communicator |

|

| ||

| I. Healthcare Planning | ||

|

| ||

| 44. | Define and describe (including the roles of physicians and substitute decision-makers) advance planning directives dealing with personal and financial decision-making, as permitted by legislation in their province of training. | Advocate, Communicator |

| 45. | Perform a capacity assessment and follow a capacity assessment process when indicated. | FM Expert, Communicator |

| 46. | Identify and manage common end of life care issues (e.g., nutrition, dysphagia, code status, hospital transfer, home and LTC visits). | FM Expert, Communicator |

| 47. | Be aware of the key principles of the Mental Health Act, Personal Directive Act, and Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act. | FM Expert |

|

| ||

| J. Professionalism | ||

|

| ||

| 48. | Day to day behavior reassures that the physician is responsible, reliable, and trustworthy (e.g., punctual, answers pager). | Professional |

| 49. | The physician knows his/her limits of clinical competence and seeks help appropriately. | Professional |

| 50. | The physician demonstrates a flexible, open-minded approach that is resourceful and deals with uncertainty. | Professional |

| 51. | The physician evokes confidence, without arrogance and does so even when needing to obtain further information or assistance. | Professional |

| 52. | The physician demonstrates a caring and compassionate manner (e.g., actively listen, asks about feelings). | Professional |

| 53. | The physician demonstrates respect for patients in all ways, maintains appropriate boundaries, and is committed to patient well-being. This includes time management, availability, and a willingness to assess performance. | Professional |

| 54. | The physician demonstrates respect for colleagues and team members. | Professional |

| 55. | Day to day behavior and discussion reassures that the physician is ethical and honest (e.g., informed consent, patient autonomy). | Professional |

| 56. | The physician practices evidence-base medicine skillfully. This implies not only critical appraisal and information management capabilities but incorporates appropriate learning from colleagues and friends. | Professional |

| 57. | The physician displays a commitment to societal and community well being. | Professional |

| 58. | The physician displays a commitment to personal health and seeks balance between personal life and professional responsibilities. | Professional |

| 59. | The physician demonstrates a mindful approach to practice by maintaining composure/equanimity, even in difficult situations and by engaging in thoughtful dialogue about values and motives. | Professional |

| 60. | Appropriate attitudes for managing elderly patients—patient advocate, tolerance of ambiguity, inquiring mind. | Professional |

| 61. | Comprehensive approach that respects patient autonomy. | Professional |

| 62. | Respects other members of the health care team and fosters an interdisciplinary approach. | Professional |

| 63. | Demonstrates an open attitude and willingness to teach other learners. | Professional |

|

| ||

| K. Communication | ||

|

| ||

| i) | With Patients | |

| 64. | Language skills both verbal and written must be adequate to be understood by the patient—open to closed questions, limits jargon. | Communicator |

| 65. | Listening skills—uses both general and active listening skills to facilitate communication—lets the patient tell their story. | Communicator |

| 66. | Non-verbal skills—both expressive and receptive body language—sitting, eye contact, responds to patient’s discomfort. | Communicator |

| 67. | Culture and age appropriateness – adapts communication to the individual patient for reasons such as culture, age, and disability. Use collateral sources to obtain history. | Communicator |

| ii) | With Colleagues | |

| 68. | Language skills both verbal and written adequate to understand complex profession specific conversation. | Communicator |

| 69. | Charting and Consult Letter skills—legible, organized, timely. | Communicator |

| 70. | Listening skills—attentive. | Communicator |

| 71. | Non-verbal skills—expressive (e.g., eye contact, body language) and receptive. | Communicator |

|

| ||

| L. Research | ||

|

| ||

| 72. | Formulate a research question. | Scholar |

| 73. | Conduct a literature search. | Scholar |

| 74. | Choose appropriate literature. | Scholar |

| 75. | Design project methodology. | Scholar |

| 76. | Complete a Health Research Ethics Board ethics application. | Scholar |

| 77. | Complete chart reviews with accuracy. | Scholar |

| 78. | Assist with data analysis. | Scholar |

| 79. | Accurately interpret data. | Scholar |

| 80. | Develop a presentation using PowerPoint. | Scholar |

| 81. | Present data in PowerPoint format. | Scholar |

| 82. | Present research in a public forum. | Scholar |

| 83. | Develop critical thinking skills as evidenced by the ability to ask questions related to data interpretation and to draw accurate conclusions from the research data. | Scholar |

| 84. | Acquires practical research skills. | Scholar |

| 85. | Acquires practical research knowledge. | Scholar |

ACEI = angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, BPSD = behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, CHF = congestive heart failure, FTD = frontal temporal dementia, LBD = Lewy body dementia, CJD = Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, LTC = long-term care, MDS = myelodysplastic syndromes, NMDA = N-Methyl-D-Aspartate, UI = urinary incontinence

TABLE A.2.

CanMEDS-Family Medicine Roles(20)

| Family Medicine Expert | Family physicians are skilled clinicians who provide comprehensive, continuing care to patients and their families within a relationship of trust. The role of the Family Medicine Expert draws on the competencies included in the roles of Communicator, Collaborator, Manager, Health Advocate, Scholar, and Professional. |

| Communicator | As Communicators, family physicians facilitate the doctor-patient relationship and the dynamic exchanges that occur before, during, and after the medical encounter. |

| Collaborator | As Collaborators, Family physicians work with patients, families, health-care teams, other health professionals, and communities to achieve optimal patient care. |

| Manager | As Managers, family physicians are central to the primary health-care team and integral participants in health-care organizations. They use resources wisely and organize practices which are a resource to their patient population to sustain and improve health, coordinating care with the other members of the health-care system. |

| Health Advocate | As Health Advocates, family physicians responsibly use their expertise and influence to advance the health and well-being of individual patients, communities, and populations. |

| Scholar | As Scholars, physicians demonstrate a lifelong commitment to reflective learning, as well as the creation, dissemination, application, and translation of medical knowledge. |

| Professional | As Professionals, physicians are committed to the health and well-being of individuals and society through ethical practice, profession-led regulation, and high personal standards of behaviour. |

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada . Seniors in Canada. Catalogue No.: 85F0033MIE. Ottawa, ON: Author; 2001. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/Collection/Statcan/85F0033M/85F0033MIE2001008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada The Canadian population in 2011: Age and sex. Catalogue No.: 98-311-X2011001. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011001-eng.pdf.

- 3.Turcotte M, Schellenberg G. A portrait of seniors in Canada Catalogue No: 89-519-XIE. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2007. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-519-x/89-519-x2006001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):373–83. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasmith L, Ballem P, Baxter R, et al. Transforming care for Canadians with chronic health conditions: put people first, expect the best, manage for results. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacAdam M. Frameworks of integrated care for the elderly: a systematic review. Toronto, ON: Canadian Policy Research Networks; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reuben DB, Zwanziger J, Bradley TB, et al. How many physicians will be needed to provide medical care for older persons? Physician manpower needs for the twenty-first century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(4):444–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mold JW, Mehr DR, Kvale JN, et al. The importance of geriatrics to family medicine: a position paper by the Group on Geriatric Education of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Fam Med. 1995;27(4):234–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Health care in Canada, 2011: a focus on seniors and aging. Ottawa, ON: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited . Healthcare strategies for an aging society. New York, NY: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank C, Seguin R. Care of the elderly training: implications for family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(5):510–511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine . Retooling for an aging America: building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Care of the Elderly Working Group . Final report on care of the elderly. Edmonton, AB: Alberta College of Family Physicians; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) Standards for accreditation of residency training programs. Mississauga, ON: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Working Group on Care of the Elderly . The report of the Working Group on Care of the Elderly to Postgraduate Education Joint Committee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada in collaboration with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oandasan I, Saucier D, editors. Triple C Competency-based Curriculum Report – Part 2: Advancing implementation. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2013. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Education/_PDFs/TripleC_Report_pt2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saucier D, Schipper S, Oandasan I, et al. Key concepts and definitions of competency-based education [PowerPoint presentation] Mississauga ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2011. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/TripleCToolkit/. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tannenbaum D, Kerr J, Konkin J, et al. The scope of training for family medicine residency: report of the working group on postgraduate curriculum review. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald CJ, McKeen M, Wooltorton E, et al. Striving for excellence: developing a framework for the Triple C curriculum in family medicine education. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(10):e555–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, et al. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(Suppl 1):48–56. doi: 10.1002/jhm.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geriatric Education and Recruitment Initiative (GERI), National Institute for Care of the Elderly (NICE) Core interprofessional competencies for gerontology. Toronto, ON: Authors; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geriatric Education and Recruitment Initiative (GERI), National Institute for Care of the Elderly (NICE) Objectives of training in psychiatry: geriatric component 2009. Toronto, ON: Authors; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monette M, Hill A. Arm-twisting medical schools for core geriatric training. CMAJ. 2012;184(10):E515–16. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmar J. Core competencies in the care of the older persons for Canadian medical students. Can J Geriatr. 2009;12(2):70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society Core competencies for the care of older patients: recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society. Acad Med. 2000;75(3):252–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mather F. Health Care of the Elderly Committee newsletter. Mississauga, ON: The College of Family Physicians Canada; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework: better standards, better physicians, better care. Ottawa, ON: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bragg EJ, Warshaw GA, Arenson C, et al. A national survey of family medicine residency education in geriatric medicine: comparing findings in 2004 to 2001. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):258–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Fried LP, et al. Which patients benefit the most from a geriatrician’s care? Consensus among directors of geriatrics academic programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1796–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warshaw GA, Thomas DC, Callahan EH, et al. A national survey on the current status of general internal medicine residency education in geriatric medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):679–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callahan CM, Weiner M, Counsell SR. Defining the domain of geriatric medicine in an urban public health system affiliated with an academic medical center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1802–06. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phelan EA, Genshaft S, Williams B, et al. How “geriatric” is care provided by fellowship-trained geriatricians compared to that of generalists? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1807–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]