Abstract

Background

The reinforcing properties of nicotine may be mediated through release of various neurotransmitters both centrally and systemically. People who smoke report positive effects such as pleasure, arousal, and relaxation as well as relief of negative affect, tension, and anxiety. Opioid (narcotic) antagonists are of particular interest to investigators as potential agents to attenuate the rewarding effects of cigarette smoking.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of opioid antagonists in promoting long‐term smoking cessation. The drugs include naloxone and the longer‐acting opioid antagonist naltrexone.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register for trials of naloxone, naltrexone and other opioid antagonists and conducted an additional search of MEDLINE using 'Narcotic antagonists' and smoking terms in April 2013. We also contacted investigators, when possible, for information on unpublished studies.

Selection criteria

We considered randomised controlled trials comparing opioid antagonists to placebo or an alternative therapeutic control for smoking cessation. We included in the meta‐analysis only those trials which reported data on abstinence for a minimum of six months. We also reviewed, for descriptive purposes, results from short‐term laboratory‐based studies of opioid antagonists designed to evaluate psycho‐biological mediating variables associated with nicotine dependence.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in duplicate on the study population, the nature of the drug therapy, the outcome measures, method of randomisation, and completeness of follow‐up. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months follow‐up in patients smoking at baseline. Abstinence at end of treatment was a secondary outcome. We extracted cotinine‐ or carbon monoxide‐verified abstinence where available. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis, pooling risk ratios using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model.

Main results

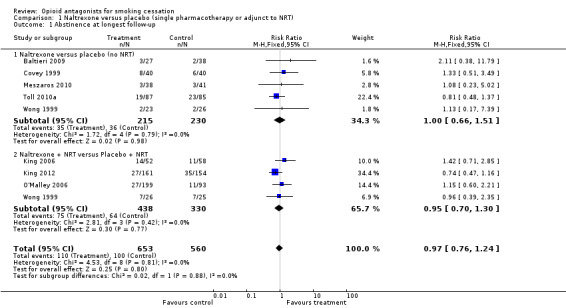

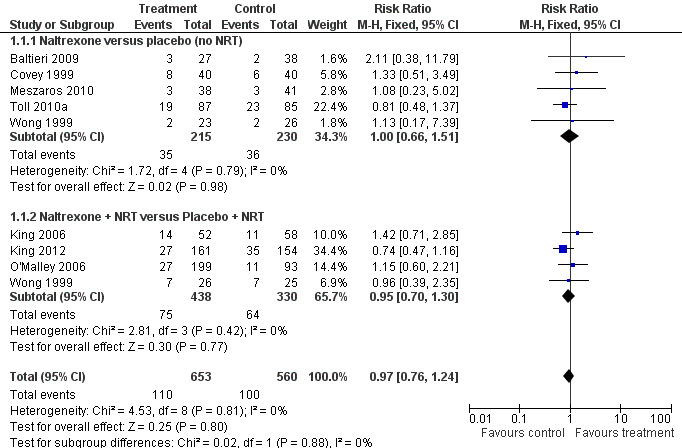

Eight trials of naltrexone met inclusion criteria for meta‐analysis of long‐term cessation. One trial used a factorial design so five trials compared naltrexone versus placebo and four trials compared naltrexone plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus placebo plus NRT. Results from 250 participants in one long‐term trial remain unpublished. No significant difference was detected between naltrexone and placebo (risk ratio (RR) 1.00; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 1.51, 445 participants), or between naltrexone and placebo as an adjunct to NRT (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.30, 768 participants). The estimate was similar when all eight trials were pooled (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.24, 1213 participants). In a secondary analysis of abstinence at end of treatment, there was also no evidence of any early treatment effect, (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.22, 1213 participants). No trials of naloxone or buprenorphine reported abstinence outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Based on data from eight trials and over 1200 individuals, there was no evidence of an effect of naltrexone alone or as an adjunct to NRT on long‐term smoking abstinence, with a point estimate strongly suggesting no effect and confidence intervals that make a clinically important effect of treatment unlikely. Although further trials might narrow the confidence intervals they are unlikely to be a good use of resources.

Keywords: Humans, Buprenorphine, Buprenorphine/therapeutic use, Naloxone, Naloxone/therapeutic use, Naltrexone, Naltrexone/therapeutic use, Narcotic Antagonists, Narcotic Antagonists/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking, Smoking/drug therapy, Smoking Cessation, Smoking Cessation/methods, Tobacco Use Cessation Devices

Plain language summary

Do opioid antagonists such as naltrexone help people to stop smoking?

Opioid antagonists are a type of drug which blunts the effects of narcotics such as heroin and morphine, and might help reduce nicotine addiction by blocking some of the rewarding effects of smoking. Our review identified eight trials of naltrexone, a long‐acting opioid antagonist. The trials included over 1200 smokers. Half the trials gave everyone nicotine replacement therapy and tested whether naltrexone had any additional benefit. Compared to a placebo, naltrexone did not increase the proportion of people who had stopped smoking, at the end of treatment, or at six months or more after treatment, either on its own or added to NRT. The available evidence does not suggest that opioid antagonists such as naltrexone assist smoking cessation.

Background

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death (USDHHS 2010). United States clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of approved cessation pharmacotherapy for quitting smoking (Fiore 2008). Evidence‐backed medications delivering abstinence at six months or longer include nicotine replacement in the form of gum, patch, lozenge, inhaler, and nasal spray (risk ratio (RR) for any NRT 1.60, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.53 to 1.68, Stead 2012); bupropion (RR 1.69; 95% CI 1.53 to 1.85, Hughes 2007); and varenicline (RR 2.27, 95% CI 2.02 to 2.55; Cahill 2012; Mills 2012; ). Effective second‐line treatments include nortriptyline (RR 2.03; 95% CI 1.48 to 2.78, Hughes 2007) and clonidine (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.74, Gourlay 2008;). However long‐term quit rates are relatively modest, in the range of 19.0% to 36.5% (Fiore 2008). With relapse as the norm, there is continued interest in other pharmacological agents for assisting cessation.

Nicotine dependence involves a complex interplay of learned or conditioned behaviours, personality, social settings, and pharmacological factors. The reinforcing properties of nicotine are theorised to be mediated in part through release of various neurotransmitters throughout the brain. Acute exposure to nicotine activates nicotinic cholinergic receptors resulting in the release of neurotransmitters including dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, vasopressin, serotonin, glutamate, gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) and beta endorphin. It has been suggested that release of beta endorphin may be associated with reduction of anxiety and tension (Benowitz 1999). Nicotine also activates nicotinic cholinergic receptors in the adrenal medulla leading to the release of epinephrine (adrenaline) and beta endorphin, which may contribute to the systemic effects of nicotine. In one study, smoking a cigarette increased beta‐endorphin levels 30 to 300%, which was significantly correlated with plasma nicotine levels (Pomerleau 1983). In addition to evidence suggesting a possible reinforcing role for the endogenous opioid system in smoking, findings from other studies suggest that this system might be involved with mediating nicotine withdrawal. Studies by Malin and colleagues indicate that the opioid antagonist naloxone precipitates nicotine withdrawal in nicotine‐maintained rats, and nicotine‐induced reversal of this withdrawal syndrome is antagonised by naloxone (Malin 1993; Malin 1996), and these and other studies have demonstrated that naloxone may actually precipitate physical and affective symptoms of nicotine withdrawal (Biala 2005; Isola 2002; Malin 1993; Malin 1996).

Opioid antagonists are typically used in the treatment of opioid dependence and alcohol dependence. The focus of this review and meta‐analysis is on evaluations of opioid antagonists for the treatment of tobacco dependence. A secondary focus is the effect of opioid antagonists on psycho‐biological mediating variables associated with nicotine dependence and smoking cessation.

Naloxone (Narcan; half‐life 30‐100 min; Goodrich 1990), a short‐acting opioid antagonist, is routinely administered to reverse the acute effects of narcotic overdose. Evidence that naloxone and related drugs may block the reinforcing properties of nicotine and affect nicotine withdrawal has led to clinical trials of naloxone to determine its effects on smoking behaviour and withdrawal symptoms.

Naltrexone (Narpan™, Revia™, Vivitrol™, half‐life 240 mins Meyer 1984), a long‐acting opioid antagonist, is a marketed drug which blunts certain effects of narcotics such as heroin, meperidine, morphine and oxycodone. It has been shown to help in the treatment of alcohol dependence (O'Malley 1995; Volpicelli 1992). Naltrexone occupies the μ‐opioid receptors, which putatively diminishes the activation of mesolimbic dopamine and therefore may reduce craving for nicotine. Thus it is believed that NRT and naltrexone could produce additive effects by reducing craving through different mechanisms of action. Naltrexone has also been studied for its utility to reduce post‐smoking cessation weight gain; a recent Cochrane review showed a modest benefit of naltrexone on reduced post‐cessation weight gain at end of treatment, but this did not persist for six months or longer (Farley 2012).

Buprenorphine (Buprenex™, Subutex™, Suboxone™, Butrans™, half‐life 24 ‐ 60 hrs; SAMHSA 2013), a mixed agonist‐antagonist, has also been evaluated in two published studies of smoking (°Mello 1985; °Mutschler 2002).

Since opioid antagonists are known to precipitate nicotine withdrawal in nicotine‐dependent animals, using them as an adjunct to NRT may have the additional benefit of attenuating the increased withdrawal, dysphoria and sedation caused by naloxone and naltrexone.

Serious adverse events are uncommon when these drugs are used in the treatment of alcohol dependence (CSAT 2009). The most common side effects have included nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, fatigue, nervousness, anxiety, and somnolence. Less common side effects include gastrointestinal distress, chest and joint/muscle pain, rash, difficulty sleeping, excessive thirst, loss of appetite, sweating, increased tears, mild depression, and delayed ejaculation. Side effects of buprenorphine are similar to those of other opioids and include nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

Objectives

The primary objective of the review was to evaluate the efficacy of opioid antagonists (including naltrexone, naloxone, buprenorphine), alone or in combination with nicotine replacement, in promoting smoking cessation. The secondary objectives of the review were to evaluate the efficacy of opioid antagonists in treating withdrawal symptoms, attenuating the reinforcing value of smoking, and reducing ad libitum smoking. In the analysis, specific opioid antagonists were considered separately rather than grouping these medications as a class. For example, studies evaluating naltrexone were compared only to other studies evaluating naltrexone and not grouped with naloxone.

The main hypotheses were: 1. Opioid antagonists are more effective than placebo in promoting sustained abstinence from smoking. 2. Opioid antagonists used in combination with nicotine replacement therapy are more effective than either opioid antagonists or nicotine replacement therapy alone in promoting sustained abstinence from smoking.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review includes two tiers of evidence. We used randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of opioid antagonists that report smoking status at least six months after intervention to assess the efficacy for long‐term cessation. We also considered RCTs of opioid antagonists with short‐term follow‐up that report the outcomes of withdrawal, reinforcing properties of smoking, or ad libitum smoking.

Types of participants

Adults who smoke.

Types of interventions

Naltrexone, naloxone, buprenorphine or other opioid antagonists, with or without concurrent nicotine replacement therapy.

Types of outcome measures

Abstinence at six months or longer was the primary outcome measure. Abstinence at end of treatment was a secondary outcome. We used a sustained cessation rate in preference to point prevalence, and biochemical verification of self‐reported quitting where reported. We regarded people lost to follow‐up as continuing smoking. We noted any adverse effects. Other secondary outcome measures included withdrawal, reinforcing or hedonic effects of smoking, mood states, and ad libitum smoking.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register in April 2013 using the terms 'naloxone' or 'naltrexone' or ' opioid antagonist*' or 'opiate antagonist*' or 'narcotic antagonist*' in the title or abstract, or as key words (see Appendix 1 for details). At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 3, 2013; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20130329; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201313; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20130401. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and list of other resources searched (CTAG Module). An additional search of MEDLINE (via OVID, to update 20130417) used the terms (explode "Narcotic‐Antagonists"/ all subheadings) AND ("Smoking‐Cessation"/ all subheadings OR "Tobacco‐Use‐Disorder"/ all subheadings OR "Smoking"/ all subheadings).

Data collection and analysis

Two authors checked the studies generated by the search strategy for relevance, according to the inclusion criteria. One author extracted data and a second author checked them. Discrepancies were resolved by mutual consent. If significant disagreement had arisen at either stage this would have been resolved with the participation of a third author, as required. We noted reasons for the non‐inclusion of studies.

Data extraction and management

The following information about each trial is reported in the table 'Characteristics of Included Studies':

Country

Criteria for recruitment (whether current smokers only, or recent quitters) and whether selected according to willingness to make a quit attempt

Other relevant inclusion/exclusion criteria for trial

Method of randomisation, blinding, allocation concealment

Smoking behaviour and characteristics of participants

Adverse events

Support measures

Primary outcome measures ‐ definition of long‐term abstinence used in review, use of biochemical validation

Secondary outcomes ‐ withdrawal symptoms, ad libitum smoking, hedonic effects

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated studies on the basis of the following items, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Measures of treatment effect

For the abstinence outcomes we extracted the numbers reported quit at longest follow‐up and at end of treatment using the strictest definition used in the study, i.e. preferring sustained over point prevalence rates, with biochemical validation where possible. We calculated risk ratios using as the denominators the numbers of patients randomised to each arm excluding any deaths and treating those who dropped out or were lost to follow‐up as continuing to smoke. We noted any deaths and adverse events in the results tables. If necessary, we contacted authors for clarification of specific points.

Data synthesis

We combined the results of studies evaluating long‐term cessation using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model for pooling risk ratios. Interventions including nicotine replacement therapy were grouped separately from those without. In previous versions of this review we used odds ratios to summarise effects, but the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group now recommends the use of risk ratios, as being less likely to be misinterpreted (Deeks 2011). Data on other outcomes were tabulated and described narratively. In a sensitivity analysis we estimated the effect at end of treatment of adding in the results from studies excluded due to lack of long‐term follow up.

Results

Description of studies

Further details are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Studies evaluating long‐term abstinence

Naltrexone:

We identified eight trials evaluating naltrexone and reporting long‐term abstinence data (six months or more).

Covey 1999 randomised 80 volunteers to either naltrexone or placebo daily for four weeks. All smokers began taking 25 mg naltrexone or placebo at least three days before the target quit date (TQD) and the dose was increased to 50 mg on the TQD. Medication was continued for four weeks and all subjects received individual counselling. The investigators reported continuous abstinence verified by saliva cotinine at three and six months.

Wong 1999 randomised 100 volunteers to receive 12 weeks of either placebo only, naltrexone only, placebo with nicotine patches, or naltrexone with nicotine patches. The naltrexone dose was 50 mg taken once daily, and the nicotine patch dose was 21 mg/24‐hour for the first eight weeks and 14 mg/24‐hour for the remaining four weeks. Treatment with naltrexone and/or the nicotine patches started on the TQD. The trial therefore contributed separate data to both the naltrexone versus placebo and the naltrexone plus NRT versus placebo plus NRT subgroups. All participants received brief (15 to 20 minutes) counselling sessions throughout the treatment phase. Brief behavioural intervention was provided at each visit. The outcomes used in the meta‐analysis were continuous abstinence at end of treatment and six months This study was part of a multicentre, partially‐blinded, 2 x 2 factorial design study of naltrexone (50 mg, active versus placebo) and nicotine patch (active versus no treatment). Three hundred and fifty subjects were enrolled at five centres in the United States. However, the authors could report only the data from the Mayo Clinic site which enrolled 100 people. We made several attempts to obtain unpublished data in order to include them for the other 250 participants, but the funder, Dupont, has not disclosed further results (Croop 2000).

King 2006 randomised 110 smokers to either naltrexone 50 mg/day or placebo for six weeks. Both groups received weekly smoking cessation counselling sessions. All participants received nicotine patch. Prolonged abstinence was assessed at eight and 24 weeks, verified by carbon monoxide (CO). Change in body weight, withdrawal symptoms, smoking urges and affect were also assessed.

O'Malley 2006 randomised 385 volunteers to four treatment conditions: placebo, 25 mg, 50 mg or 100 mg of naltrexone for six weeks. All participants also received 21 mg active nicotine patch throughout the study period, and brief weekly counselling sessions and self‐help support. Abstinence, weight gain and adverse events were the main outcomes of interest. The published report gives outcomes at six weeks. CO‐verified quit rates at six and 12 months were provided to us by the authors. The longer term outcome is used in the meta‐analysis, combining 50 mg and 100 mg dose arms.

Baltieri 2009 randomised 155 alcohol‐dependent individuals, of which 105 were smokers, to three treatment conditions: placebo, naltrexone 50 mg/day or topiramate up to 300 mg/day for 12 weeks after a one‐week alcohol detoxification period. The authors provided unpublished six‐month follow‐up abstinence data without biochemical verification. The authors also reported changes in cigarettes/day, mood and alcoholic relapse.

Meszaros 2010 randomised 79 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and comorbid alcohol and nicotine dependence to naltrexone thrice weekly (100 mg twice, + 150 mg) or placebo for 12 weeks. The authors provided unpublished six‐month follow‐up abstinence data without biochemical verification. No effects on withdrawal or cigarette consumption were reported.

Toll 2010a randomised 172 treatment‐seeking smokers and concerned about their weight to either naltrexone 25 mg a day or placebo for 27 weeks. Self‐reported abstinence with CO verification was reported at six months after the quit date. In addition, changes in body weight, cigarettes smoked per day, withdrawal and craving were assessed.

King 2012 randomised 315 treatment‐seeking smokers to either naltrexone 50 mg a day plus nicotine patch or placebo plus nicotine patch for 12 weeks. Both groups received weekly smoking cessation counselling sessions. Self‐reported CO‐validated abstinence was measured at 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. We have used the longer term outcome in the meta‐analysis. In addition, change in body weight and self‐reported ratings of smoking urges and depression symptoms were assessed.

Studies evaluating effects on other outcomes

The remaining included studies do not report long‐term abstinence and are not included in the meta‐analysis. However, they fall into our second eligible category of studies that cover withdrawal or craving, reinforcing or hedonic effects of smoking, mood states, and ad libitum smoking. Studies in this category have ° preceding the study identifier (e.g. °Boureau 1978). There was methodological heterogeneity in assessments of effects of opioid antagonists on these secondary outcomes. There were cue reactivity studies (elicited craving or withdrawal) and static (no smoking cue, unelicited craving or withdrawal) assessments of withdrawal or craving or smoking urges, and some trials combined treatment with nicotine replacement while others did not. For measures and methods with more than one trial to evaluate them, results were mixed and inconclusive.

Naltrexone:

Naltrexone was also evaluated for its effects on withdrawal syndrome, ad libitum smoking, and/or the reinforcing properties of smoking in 14 randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over or within‐subject designed studies in laboratory settings (°Brauer 1999; °Caskey 2001; °Epstein 2004; °Houtsmuller 1997; °Hutchison 1999; °King 2000; °Knott 2007; °Lee 2005; °Ray 2006; °Ray 2007; °Rohsenow 2007; °Rukstalis 2005; °Sutherland 1995; °Wewers 1998) and in eight non‐laboratory‐based randomised controlled trials (Covey 1999; King 2006; King 2012; °O'Malley 1998; O'Malley 2006; °Rohsenow 2003; Toll 2010a; Wong 1999).

Naloxone:

The studies of naloxone and buprenorphine were designed to evaluate effects on withdrawal syndrome, ad libitum smoking, and/or the reinforcing properties of smoking. Five studies of naloxone were small sample, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over or within‐subject designed studies carried out in controlled laboratory environments (°Boureau 1978; °Gorelick 1988; °Karras 1980; °Krishnan‐Sarin 1999; °Nemeth‐Coslett 1986).

Buprenorphine:

The effect of buprenorphine on amount smoked was assessed in two studies. °Mello 1985 administered buprenorphine to seven heroin addicts, and °Mutschler 2002 randomised 23 opioid‐ and cocaine‐dependent detoxification inpatients to 4 or 8 mg of buprenorphine for 12 days.

Risk of bias in included studies

Studies included in the meta‐analysis were evaluated on their attempts to control bias in randomisation, allocation, assessment and analysis. None of the eight studies was judged to be at high risk for selection bias due to inadequate randomisation or allocation concealment procedures, but three (Baltieri 2009; Covey 1999; Meszaros 2010) did not report methods in sufficient detail for the possibility of allocation bias to be discounted. Two of these studies (Baltieri 2009; Meszaros 2010) have only been reported as abstracts with limited methodological detail. All studies were described as being double‐blind. Six of the eight long‐term cessation studies confirmed abstinence with biochemical verification, the exceptions being Baltieri 2009 and Meszaros 2010. King 2006, King 2012, O'Malley 2006, Toll 2010a and Wong 1999 reported exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) verification and did not report plasma or urine cotinine (although O'Malley 2006 tested serum cotinine at baseline). Covey 1999 reported plasma cotinine concentration. Covey 1999 was assessed as being at risk of bias from attrition because drop‐out was high in both groups and occurred earlier in the naltrexone group. Ten people in the naltrexone and two in the placebo group dropped out prior to the target quit day, for reasons including drug‐related side effects. We have included these people as treatment failures.

Effects of interventions

Studies evaluating long term abstinence

Eight published studies of opioid antagonists (Baltieri 2009; Covey 1999; King 2006; King 2012; Meszaros 2010; O'Malley 2006; Toll 2010a; Wong 1999) reported long‐term abstinence data and are included in the primary outcome meta‐analysis. All of these trials evaluated the efficacy of naltrexone for smoking cessation. We summarise the results of studies of opioid antagonists evaluating other outcomes (withdrawal symptoms, ad libitum smoking, hedonic effects) below as a review of extant data with potential utility for clinical practice pending further and more generalisable studies.

Naltrexone versus placebo without NRT

Five studies with a total of 450 participants in the relevant arms contributed to this subgroup of the meta‐analysis. The pooled estimate did not detect a significant benefit for naltrexone over placebo (risk ratio (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 1.51 Analysis 1.1). All studies reported outcomes at six months. Two studies were included based on unpublished data without biochemical validation of abstinence (Baltieri 2009; Meszaros 2010). The pooled estimate was not sensitive to the exclusion of these studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Naltrexone versus placebo (single pharmacotherapy or adjunct to NRT), Outcome 1 Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

Naltrexone versus placebo as an adjunct to NRT

Four studies with a total of 768 participants in the relevant arms contributed to this subgroup. We used the 100 mg and 50 mg arms from the O'Malley 2006 study.The pooled results from the relevant arms in these four studies did not give any indication of a treatment effect for naltrexone as an adjunct to the nicotine patch (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.30). Including the 25 mg arm of the O'Malley 2006 study in the meta‐analysis left the RR virtually unchanged.

There was no evidence of heterogeneity in subgroups with or without NRT. We also pooled both subgroups to estimate the effect of naltrexone irrespective of the use of NRT. The pooled estimate gave no evidence of a treatment effect (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.24, 1213 participants Figure 1; Analysis 1.1).

1.

Naltrexone versus placebo (single pharmacotherapy or adjunct to NRT), Abstinence at longest follow up.

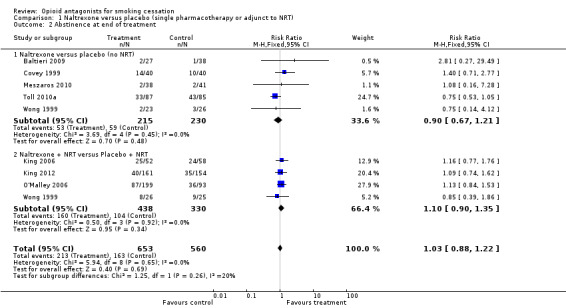

Short‐term outcomes of long‐term studies

In the absence of any evidence of long‐term effect, we did a secondary analysis using end‐of‐treatment outcomes (week 6 for Toll 2010a which provided 27 weeks of treatment). This supported the longer‐term analysis, showing no evidence that there was any early treatment effect either, and with a slightly narrower confidence interval (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.22, Analysis 1.2). Since three studies (Byars 2005; Krishnan‐Sarin 2003; Toll 2010b) that reported only short‐term outcomes had been excluded, we also did a sensitivity analysis including them in the short‐term analysis. The additional 116 participants from these trials did not greatly alter the estimates (RR 1.09 95% CI 0.93 to 1.27, data not shown).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Naltrexone versus placebo (single pharmacotherapy or adjunct to NRT), Outcome 2 Abstinence at end of treatment.

Studies evaluating effects on withdrawal symptoms

Naltrexone:

Ten studies indicated no effect of naltrexone on withdrawal symptom scores (°Brauer 1999; Covey 1999; °Houtsmuller 1997; °King 2000; King 2006; °Knott 2007; °Lee 2005; °Sutherland 1995; Toll 2010a; Wong 1999), while five studies reported reductions in withdrawal or smoking urge symptoms (°Caskey 2001; King 2006; King 2012; °Lee 2005; O'Malley 2006). Three trials indicated diminished withdrawal symptoms following provocative smoking cues during sustained abstinence (°Epstein 2004; °Hutchison 1999; °Rohsenow 2007) and one trial (O'Malley 2006) reported reduced withdrawal but only at the 100 mg dose compared to placebo and not at lower dose. °Ray 2007 reported that naltrexone reduced the enhancing effect of ethanol on smoking urge symptoms but had no main effect on smoking urges.

Naloxone:

°Wewers 1998 found no significant difference in withdrawal symptoms or mood states between the naloxone and control groups. °Gorelick 1988 did not find any impact of naloxone on withdrawal. °Krishnan‐Sarin 1999 found that naloxone apparently increased urge to smoke (craving) and tiredness at lower dosages.

Studies evaluating ad libitum smoking

Naltrexone:

The results regarding ad libitum smoking were mixed. There were no significant effects of naltrexone on ad libitum smoking in three of the laboratory‐based trials (°Brauer 1999; °Houtsmuller 1997; °Sutherland 1995). However, six trials (°Caskey 2001; °Epstein 2004; °King 2000, °Lee 2005; °Olmstead 2002; °Rohsenow 2003) demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the number of cigarettes smoked ad libitum. Four trials designed to evaluate abstinence and other outcomes during smoking cessation (King 2012; O'Malley 2006; Toll 2010a; Wong 1999) reported effects of naltrexone on daily or weekly smoking during and/or after treatment with naltrexone. Wong 1999 did not find any association between naltrexone and the number of cigarettes smoked among continuing smokers. O'Malley 2006 reported that cigarettes per week increased more in the placebo group compared to the naltrexone group at only the 100 mg dose of naltrexone, whilst King 2012 and Toll 2010a reported significantly lower weekly cigarettes smoked in the naltrexone (versus placebo) arms of the respective trials. Baltieri 2009 and Meszaros 2010 reported no difference in cigarettes per day between naltrexone and placebo groups.

Naloxone:

The results for naloxone are mixed. °Gorelick 1988 and °Karras 1980 found significant reductions in number of cigarettes smoked in the naloxone group compared with placebo. However, °Nemeth‐Coslett 1986 did not find an effect of naloxone over a wide range of dosages for any measure of cigarette smoking, including number of cigarettes, number of puffs, or expired air carbon monoxide.

Buprenorphine:

°Mello 1985 found that cigarette consumption by seven heroin addicts increased compared to the pre‐buprenorphine baseline. °Mutschler 2002 detected a significant increase among detoxified opioid‐ and cocaine‐dependent inpatients in the rate of ad libitum smoking with buprenorphine administration.

Studies evaluating reinforcing effects of smoking

Naltrexone:

Studies have reported mixed results for the effect of naltrexone on hedonic effects. °Sutherland 1995 did not find any significant effect of naltrexone on self‐reported satisfaction from smoking. °Wewers 1998 found a significant reduction in self‐reported satisfaction with smoking for subjects treated with naltrexone compared to placebo. °Brauer 1999 found that naltrexone increased negative mood following smoking. °King 2000 found that naltrexone significantly reduced post‐cigarette craving and increased lightheadedness, dizziness, and head rush following a cigarette. °Ray 2006 did not observe any effect of naltrexone on smoking reinforcement. However, °Rohsenow 2007 found that naltrexone did not affect reinforcing or aversive measures of smoking.

Naloxone:

Neither °Gorelick 1988 nor °Karras 1980 found an effect of naloxone on the reinforcing properties of smoking cigarettes.

Discussion

Eight trials of naltrexone with a total of 1213 smokers randomised to naltrexone at doses of 25 ‐ 100 mg/day or placebo tablets have now reported long‐term abstinence data. The point estimate for the risk ratio (RR) pooling all studies, 0.97 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 1.24), suggests that naltrexone has no effect on abstinence whether used alone or in combination with NRT. The addition of four studies in this update has narrowed the confidence interval sufficiently to conclude that the likelihood of any clinically important effect is very small. The consistency of the effects seen so far suggest that further research is only likely to reduce the CI around no effect. We also know that one study remains unpublished, the likelihood being that it too did not detect evidence of benefit (Croop 2000). Further studies would probably strengthen the evidence of lack of benefit, but may not be the best use of resources. In a secondary analysis added for this update we pooled short‐term outcomes, which also showed no evidence of any early treatment effect. Three randomised clinical trials with a total of 116 participants were excluded because of lack of assessing or reporting long‐term abstinence rates, and including their results in the short‐term analysis did not affect the conclusions. By comparison, the RR of long‐term abstinence rates for NRT from 117 trials with over 50,000 participants was 1.60 (95% CI 1.53 to 1.68) (Stead 2012).

At least three study reports (Covey 1999; King 2006; King 2012) raised the possibility that there could be a difference in effect by gender, with women showing more evidence of a benefit than men. The other five abstinence studies (Baltieri 2009; Meszaros 2010; O'Malley 2006; Toll 2010a; Wong 1999) did not report quit rates for men and women separately, so we could not conduct a meta‐analysis without risk of reporting bias.

Although not an end point of this systematic review, it should be noted that the King 2006 and King 2012 studies showed significant benefits of naltrexone for reducing post‐cessation weight gain, but Toll 2010a did not find a significant effect of naltrexone for this outcome. The effects on weight gain are evaluated in a separate Cochrane review (Farley 2012). There are mixed results with regard to whether or not naltrexone reduces withdrawal symptoms, diminishes the reinforcing effects of nicotine and tobacco or reduces post‐cessation weight gain. However, because of heterogeneity of methods and data reporting we are unable to examine withdrawal symptoms and reinforcing effects using meta‐analytic techniques. Also, we do not have enough data to examine whether or not the use of combination naltrexone and nicotine replacement has a significant effect on withdrawal symptoms compared to nicotine replacement plus placebo.

There were no clear trends suggesting positive or negative effects of naloxone on withdrawal, ad libitum smoking or hedonic effects. In any case, the very short half‐life, and route of administration of naloxone (intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous) precludes its use as an agent for smoking cessation in clinical settings.

Given the purported role of opioid pathways in nicotine dependence, it would seem biologically plausible that opioid antagonists would blunt the rewarding effects of smoking. Moreover, we would expect, if opioid antagonists diminished the reinforcing properties of smoking, that this would translate to decreased tobacco consumption or ad libitum smoking. However, we found no such trends. This lack of observed effects of opioid antagonists on smoking rates and aversive or reinforcing properties of nicotine is consistent with a study in rats that showed no effect on nicotine self administration (Corrigall 1991).

A large body of converging evidence suggests that nicotine stimulates the release of dopamine in the mesocorticolimbic system and plays an important role in the reinforcing properties of smoking. Blum 1995 and others have suggested that individuals may be at higher risk for dependence on nicotine and other substances because of deficiencies in dopamine transmission in the mesocorticolimbic system. However, the neurobiology of nicotine addiction is complex and involves interactions between multiple neurotransmitter systems (Benowitz 2010). The dopamine re‐uptake inhibitor bupropion appears to diminish the rewarding effects of smoking and also appears to decrease withdrawal (Shiffman 2000) and the nicotine receptor partial agonist varenicline has shown similar effects (Brandon 2012). While we cannot draw any firm conclusions on the effect of opioid antagonists on the reinforcing properties of smoking or withdrawal, the literature to date suggests that dopamine and other interacting pathways play a more important role in nicotine dependence.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The current evidence suggests that the clinical use of naltrexone or other opioid antagonists is of no benefit for smoking cessation.

Implications for research.

Further research is unlikely to change the conclusion of lack of benefit.

Longer‐term smoking cessation outcomes data (six months or more), if collected by investigators in past, present, or future studies, should be made available in the public domain, to improve the reliability and generalisability of meta‐analyses for smoking cessation medications such as opioid antagonists and other classes of pharmacological agents.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 April 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. Four new studies with long term outcomes. |

| 18 April 2013 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Evidence supports absence of a treatment effect. Meta‐analysis of short term outcomes added. Judith Prochaska became a co‐author. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 3, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 June 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated for issue 4, 2009. No new long term cessation studies, four laboratory/ short term studies |

| 29 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 9 August 2006 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated for issue 4, 2006. Two new studies with long term cessation data. Dr Eden Evins became a co‐author. |

| 24 October 2002 | New citation required and minor changes | Updated for issue 1, 2003. One new study of effect of buprenorphine on ad libitum smoking, not relevant to clinical intervention |

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Drs Baltieri, Batki, Hutchison, Niaura, O'Malley and Szombathyne‐Meszaros for assistance with additional information or data on studies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Register search strategy

| 1 | (naloxone):AB,TI,MH,EMT,KY,XKY | 8 |

| 2 | (naltrexone):AB,TI,MH,EMT,KY,XKY | 82 |

| 3 | (opioid antagonist*):AB,TI,MH,EMT,KY,XKY | 15 |

| 4 | (opiate antagonist*):AB,TI,MH,EMT,KY,XKY | 10 |

| 5 | (narcotic antagonist*):AB,TI,MH,EMT,KY,XKY | 31 |

| 6 | opioid*:XKY | 36 |

| 7 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 | 102 |

| 8 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) AND (INREGISTER) | 85 |

| 9 | 2009 or 2010 or 2011 or 2012 or 2013:YR | 5231 |

| 10 | #8 AND #11 | 23 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Naltrexone versus placebo (single pharmacotherapy or adjunct to NRT).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abstinence at longest follow‐up | 8 | 1213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

| 1.1 Naltrexone versus placebo (no NRT) | 5 | 445 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.66, 1.51] |

| 1.2 Naltrexone + NRT versus Placebo + NRT | 4 | 768 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.70, 1.30] |

| 2 Abstinence at end of treatment | 8 | 1213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.88, 1.22] |

| 2.1 Naltrexone versus placebo (no NRT) | 5 | 445 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.67, 1.21] |

| 2.2 Naltrexone + NRT versus Placebo + NRT | 4 | 768 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.90, 1.35] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baltieri 2009.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: Brazil Recruitment: Unclear Design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 155 male alcohol‐dependent outpatients (52 nonsmokers and 103 smokers), 18 – 60 years of age, with ICD‐10 diagnosis of alcohol dependence | |

| Interventions | 1) Naltrexone 50 mg/day for 12 wks 2) Placebo 3) Topiramate up to 300 mg/day (not used in this review) After a 1‐wk alcohol detoxification period |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking abstinence at 12 wks (EOT) and 6 months from baseline, time to first relapse, adherence to treatment, cigarettes smoked/day, mood | |

| Notes | Only smokers included in meta‐analysis. No biochemical verification of abstinence. Unpublished 6‐month data provided by authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomised", method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Medication was dispensed under double‐blind conditions. Only two pharmacists from the pharmacy sector ... knew which medication corresponded to the specific code. The packages containing the capsules were distributed to patients by two blinded research assistants, who also assessed patient outcomes throughout the study. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "patients received standardized brief cognitive behavioural interventions from their doctors who were blind to medication conditions"; "Medications codes were revealed to researchers only after all patients had completed the study." (Baltieri 2008) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Drop‐out rates 40.8% naltrexone, 57.4% placebo, |

Covey 1999.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: By notices at University and newspaper adverts Design: Randomised double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | 80 smokers, ≥ 20 cpd, age 18 ‐ 65, smoked before leaving house in morning, had made at least 1 quit attempt, and experienced withdrawal symptoms during quit attempt | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 25 mg/day at least 3 days before TQD, increased to 50 ‐ 75 mg/day on quit date and continued for 4 wks 2. Placebo Both groups received weekly individual behavioural counselling | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported continuous abstinence at 4 wks and 6 months, verified at all visits by plasma cotinine ≤15 ng/mL Mood | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned"; method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | no details given |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "double‐blind" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Subject drop‐out high and differential. 32.5% (n = 13) dropped out in naltrexone group; 32.5% (n = 13) also dropped out in placebo group. However 10/13 drop‐outs in naltrexone group occurred before quit date for wide range of side effects or excuses. All drop‐outs included as smokers in meta‐analysis |

King 2006.

| Methods | NALTREXONE AS AN ADJUNCT TO NICOTINE PATCH

Country: USA

Recruitment: Newspaper adverts, flyers, word of mouth Design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 110 smokers (15 ‐ 40 cpd), 51% F, av age 44 | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 25 mg for 3 days then 50 mg for 2 months, nicotine patch for 1month 2. Placebo + nicotine patch All participants received 6 individual 45 ‐ 60 mins behavioural therapy sessions | |

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence at 8 wks (EOT) and 24 wks, validated by CO ≤10 ppm Smoking urges, withdrawal, side effects, body weight changes | |

| Notes | Preliminary results presented in King 2002, King 2003. Gender difference noted in outcomes | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomly assigned via a computer‐generated random number list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Both subjects and trial staff were blinded to study medication assignment" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Both subjects and trial staff were blinded to study medication assignment" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 8/52 naltrexone, 13/58 placebo lost to follow‐up, all included as smokers in meta‐analysis. |

King 2012.

| Methods | NALTREXONE AS AN ADJUNCT TO NICOTINE PATCH Country: USA Recruitment: Internet, print and radio Randomisation: Stratified by gender |

|

| Participants | 315 treatment‐seeking smokers Subjects were eligible if they were 18 to 65 years old, smoked 10 ‐ 40 cpd for at least 2 years, had a body mass index (kg/m²) of 19 to 38, had a breath CO ≥10 ppm, and a urinary Nicalert reading > 500 ng/mL cotinine, confirming regular smoking |

|

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone (50 mg/day) x 12 wks plus nicotine patch (21 mg/day x 2 wks, 14 mg/day x 1 wk, 7 mg/day x 1 wk) 2. Placebo x 12 wks, + nicotine patch (same schedule) |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence at 12 wks (EOT), 6 and 12 months verified with expired air CO, cpd Self‐reported ratings of smoking urges and depression symptoms | |

| Notes | 12w & 12m outcomes used in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomly assigned by computer" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Participants and study staff were blinded to treatment assignment" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Participants and study staff were blinded to treatment assignment" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 7 Naltrexone, 11 Placebo did not start treatment, not included in MA. All other drop‐outs included as smokers in meta‐analysis |

Meszaros 2010.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Unclear Design: Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 79 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and comorbid alcohol and tobacco dependence Subjects in alcohol treatment trial were eligible if ages 18 to 69, DSM‐IV schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder w/psychotic features, bipolar type I or II or psychosis and alcohol dependence, but not opioid dependence |

|

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 3 times/wk (100 mg Mon and Tue; 150 mg Fri) x 3 months 2. Placebo (same schedule) |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence at 12 wks (EOT), 6 months, cpd | |

| Notes | Not yet published in full. Conference abstract and data from author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomised, method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "Double‐blind" no further details |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | All randomised participants included in denominators |

O'Malley 2006.

| Methods | NALTREXONE AS AN ADJUNCT TO NICOTINE PATCH Country: USA Recruitment: Patients at a Connecticut mental health centre and a VA healthcare centre, recruited through press, advertisements and mailings to physicians Design: Double‐blind randomised controlled trial, to test effects of naltrexone, with and without NRT, on smoking cessation and on weight gain. Block randomisation stratified by gender after 150 enrolments. Allocation by random sequence provided to pharmacist | |

| Participants | 385 smokers (from 400 eligible), age ≥ 18, ≥ 20 cpd, CO > 10 ppm 46% F, av cpd 28, av age 46 | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 100 mg 2. Naltrexone 50 mg 3. Naltrexone 25 mg 4. Placebo All participants also received 21 mg NRT patch x 6 wks, initial 45 min counselling session, weekly 15 min counselling sessions for 6 wks, plus self‐help materials including dietary and exercise tips | |

| Outcomes | PPA at 12 months (also 6 months, and 6 wk continuous abstinence) validated by expired CO < 10ppm Adverse events | |

| Notes | Analyses were ITT and per protocol (completers); weight change was a secondary outcome. 50 mg and 100 mg dose groups combined in main analysis. Sensitivity analysis using individual groups, and 6 month outcomes did not alter conclusions. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomized in blocks to treatment arms, with stratified (for sex) randomization implemented after the first 150 participants to ensure that the important predictor, sex,would be distributed similarly among treatment groups." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Random sequence was provided to the pharmacist, who assigned participants; others were blinded to treatment assignment." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | " ... others were blinded to treatment assignment." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 15/400 who did not start treatment excluded from analyses. All other losses included as smokers in meta‐analysis |

Toll 2010a.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Adverts, mailings, fliers, healthcare provider referrals, press releases and websites Design: Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 172 treatment‐seeking smokers Subjects were eligible if "weight‐concerned", 18 yrs or older, at least 1 prior quit attempt, had a breath CO ≥ 10 ppm, smoked > 10 cpd x ≥1 yr |

|

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone (25 mg/day) x 27 wks 2. Placebo x 27 wks |

|

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence to 6 wks and 6 months verified with expired air CO, cigarettes smoked/wk, withdrawal and craving | |

| Notes | Study stopped early after interim analysis. Abstinence at 6 wks used for short‐term/EOT analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "... blocked stratified (for gender) randomization ..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Random sequence was provided by one of the authors (RW) to the pharmacist who assigned participants; all others were blind to treatment assignment." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | See above |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 28/87 naltrexone and 30/85 placebo completed treatment. All randomized participants included in analyses, losses classified as smoking. |

Wong 1999.

| Methods | NALTREXONE AS AN ADJUNCT TO NICOTINE PATCH

Country: USA

Recruitment: Adverts and press releases

Randomisation: By subject after stratification by gender Design: Randomised, partially‐blinded, 2 x 2 factorial trial using naltrexone |

|

| Participants | 100 smokers, ≥ 10 cpd at least 1 yr, age 18 ‐ 65, baseline CO ≥ 15 ppm without history of depression or alcohol/drug dependence | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 50 mg/day for 12 wks 2. Nicotine patch (21 mg 8 wks/14 mg 4 wks) + placebo pill 3. Naltrexone (50 mg/day) + nicotine patch (21/14) for 12 wks 4. Placebo pill for 12 wks. All groups received weekly counselling. No placebo patches used | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence to 12 wks (EOT) and 6 months verified with expired air CO, cpd Self‐reported ratings of urges and craving | |

| Notes | Data reported from only 1 of 5 centres involved in study. Additional data sought from the DuPont Merck Pharmaceutical Company but was not provided (Croop 2000). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computer generated randomization schedules prepared by the clinical operations group of the study sponsor." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Identification numbers were randomized to the medication kits ... Randomization schedules were retained by the study sponsor in sealed envelopes." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Partially blinded, NRT condition open |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Differential loss to follow‐up; 31% placebo, 61% naltrexone, 12% placebo + NRT, 27% naltrexone + NRT. |

°Boureau 1978.

| Methods | NALOXONE Country: France Recruitment: Not clear, abstract only Design: Laboratory‐based, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over study | |

| Participants | 20 smokers, 35% F | |

| Interventions | 1. Naloxone 0.4 mg 2. Placebo |

|

| Outcomes | Number of cigarettes smoked per day | |

| Notes | Not long‐term abstinence | |

°Brauer 1999.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Newspaper adverts Design: Laboratory, double‐blind, double‐dummy, within‐subject trial | |

| Participants | 19 smokers aged 18 ‐ 55, smoked ≥ 20 cpd for at least 2 yrs, in good health | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 50 mg plus placebo patch 2. Placebo tablet plus nicotine patch 3. Naltrexone plus nicotine patch 4. Placebo tablet plus placebo patch 1 week on each condition, day 7 smoked normal and denicotinized cigarettes in laboratory Abstinence not attempted | |

| Outcomes | Cigarette satisfaction, depression, withdrawal symptoms, mood, smoking behaviour, cardiovascular measures, and cognitive and psychomotor performance | |

| Notes | No attempt at ascertaining abstinence | |

°Caskey 2001.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Not clear, abstract only Design: Randomised, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 16 smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. Naltrexone 100 mg 2. Naltrexone 50 mg 3. Placebo | |

| Outcomes | Smoking topography, urge to smoke, serum nicotine and cotinine | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°Epstein 2004.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Flyers and newspaper adverts Design: Within‐subject, placebo‐controlled laboratory study |

|

| Participants | 44 regular smokers, 48% F | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 mg/day and placebo in random sequence | |

| Outcomes | Ad lib smoking, smoking urges, positive and negative affect, withdrawal symptoms, exhaled CO | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°Gorelick 1988.

| Methods | NALOXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Hospital employees and outpatients Design: Laboratory, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial | |

| Participants | 10 male chronic smokers with severe nicotine dependence (mean FTQ score of 7.4 and past failure to quit smoking) | |

| Interventions | Each subject evaluated in 2 laboratory sessions receiving either naloxone 10 mg sc or placebo (drug vehicle) | |

| Outcomes | Number of cigarettes smoked, CO content of expired air, subjective aspects of smoking and withdrawal, physiologic data | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°Houtsmuller 1997.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: No data given in abstract on recruitment Design: Laboratory, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, within‐subject trial | |

| Participants | 14 smokers. No data given in abstract on gender, age, inclusion or exclusion criteria | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 mg/day and placebo for 4 days each, with 10‐day washout period between | |

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms, ad lib smoking using smoking topography measures | |

| Notes | Did not report hedonic effects or ad lib smoking | |

°Hutchison 1999.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Newspaper adverts and flyers Design: Laboratory, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | 20 smokers, ≥ 20 cpd | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 + nicotine patch vs placebo pill + nicotine patch. Cue reactivity evaluate after 9‐hr abstinence | |

| Outcomes | Nicotine dependence severity, (FTQ), positive and negative affect, withdrawal symptoms | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°Karras 1980.

| Methods | NALOXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Unclear from manuscript Design: Laboratory‐based double‐blind, drug‐placebo, cross‐over trial | |

| Participants | 7 smokers, employees at medical centre, ≥ 20 cpd | |

| Interventions | Naloxone 10 mg/ml or 1ml or placebo sc | |

| Outcomes | Number of puffs smoked, weight of smoked portion, desire for cigarette, satisfaction, mood, side effects | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°King 2000.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Adverts Design: Laboratory‐based, randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled within‐subject trial | |

| Participants | 22 regular cigarette smokers aged 19 ‐ 50. Excluded if history of major psychiatric illnesses or positive blood or urine toxicology for cocaine, opiates, benzodiazepines, amphetamine, barbiturates, and phencyclidine | |

| Interventions | Each subject participated in 2 identical testing sessions in double‐blind study. Sessions spaced 8 days apart. Each subject received pre‐administration of either 50 mg naltrexone or identical placebo in random order, after overnight abstinence. Offered up to 4 cigs over 2 hrs | |

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms and ad lib smoking | |

| Notes | No long‐term abstinence data | |

°Knott 2007.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: Canada

Recruitment: Not described Design: Laboratory‐based, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 18 smokers, ≥ 10 cpd, 40% F, av age 23 | |

| Interventions | Four sessions: 1. 2‐sessions active naltrexone 50 mg; 2. 2‐sessions placebo tablets; 3. 2‐session nicotine gum 4 mg; 4. 2‐session placebo gum |

|

| Outcomes | Change in withdrawal symptoms or hedonic effects of nicotine | |

| Notes | ||

°Krishnan‐Sarin 1999.

| Methods | NALOXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Newspaper adverts in community Design: Laboratory‐based, single group, within‐subject design | |

| Participants | 9 smokers (smoked 1 ‐ 1½ packs per day) and 11 non‐smoking volunteers | |

| Interventions | Naloxone in dosages of 0, 0.8, and 1.6 mg iv | |

| Outcomes | Narcotic withdrawal scale, smoking urges, blood cortisol levels | |

| Notes | Did not report ad lib smoking or hedonic effects | |

°Lee 2005.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: South Korea

Recruitment: Not clear, apparently recruited from clinical setting Design: Randomised, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 25 male smokers | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 25 mg/day x 7 days, then 50 mg/day x 7 days vs placebo | |

| Outcomes | Daily cigarette consumption, exhaled CO, nicotine dependence severity, ACTH, cortisol, prolactin, beta‐endorphin, dynorphin | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported | |

°Mello 1985.

| Methods | BUPRENORPHONE Country: USA Recruitment: From drug rehabilitation clinic Design: Laboratory‐based, single group, within‐subject design | |

| Participants | 7 heroin addicts | |

| Interventions | Buprenorphine ascending dosages (0.5 ‐ 8mg/day) | |

| Outcomes | Number of cigarettes smoked | |

| Notes | Did not report hedonic effects or withdrawal symptoms | |

°Mutschler 2002.

| Methods | BUPRENORPHONE Country: USA Recruitment: Pts admitted to a clinical research ward for concurrent opioid and cocaine dependence Design: Randomised trial with randomisation to 4 mg or 8 mg of buprenorphine | |

| Participants | 23 adult men with DSM III‐R diagnosis of concurrent opioid and cocaine dependence | |

| Interventions | Buprenorphine with randomisation to 4 or 8 mg/day with ascending dosages following 6 days of detoxification on methadone | |

| Outcomes | Smoking topography, urge to smoke, serum nicotine and cotinine | |

| Notes | Did not report hedonic effects or withdrawal symptoms | |

°Nemeth‐Coslett 1986.

| Methods | NALOXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: From clinical setting Design: Laboratory‐based, within‐subject |

|

| Participants | 7 smokers | |

| Interventions | Injection of naloxone HCl (0.0625, 0.25, 1.0, or 4.0 mg/kg) or placebo. Each subject received each treatment 3 times in a mixed order across days | |

| Outcomes | Number of cigarettes smoked, number of puffs, exhaled CO | |

| Notes | Did not report abstinence outcomes | |

°O'Malley 1998.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: No information given in abstract regarding recruitment Design: Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, factorial design | |

| Participants | 60 smokers who were not alcohol‐dependent. No other data provided in abstract | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 mg/day orally or similar dose placebo pill and assignment to 1 of 3 nicotine patch conditions: 1. 21 mg for 4 wks; 2. 21 mg for 2 wks followed by 14 mg and 7 mg for 1 wk each; 3. No patch |

|

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms, ad lib smoking, self‐reported abstinence at 4 wks. | |

| Notes | No specific data on number randomised to each group or number abstinent at 4 wks given | |

°Olmstead 2002.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Not described Design: Laboratory‐based, within‐subject design |

|

| Participants | 29 smokers: > 15 cpd (N = 19) or < 6 cpd (N = 10). | |

| Interventions | Repeated measures, 12‐hr sessions x 3 randomised by sequence to naltrexone 100 mg/day, 50 mg/day, and placebo | |

| Outcomes | Smoking topography, smoking urges, serum cotinine and nicotine, exhaled CO | |

| Notes | No abstinence data reported. | |

°Ray 2006.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Not described Design: Laboratory‐based, within‐subject design |

|

| Participants | 30 smokers, ≥ 10 cpd, 37% F, av age 43, av cpd 22 | |

| Interventions | Lab‐based, counterbalanced design randomised within‐subjects comparison of nicotinised (0.6 mg) vs denicotinised (0.05 mg) cigarettes | |

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms, craving | |

| Notes | ||

°Ray 2007.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Not described Design: Laboratory‐based, within‐subject design |

|

| Participants | 10 smokers (heavy drinkers), 20% F, av age 22, av cpd 5 | |

| Interventions | Laboratory‐based, quasi‐experimental, repeated‐measures study with 2 counterbalanced sessions of 1. naltrexone 50 mg; 2. placebo tablet; + iv etoh (alcohol) challenge | |

| Outcomes | Alcohol and cigarette craving | |

| Notes | ||

°Rohsenow 2003.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: From subjects enrolled in a trial of naltrexone for alcohol use outcomes Design: Randomised, placebo‐controlled trial |

|

| Participants | 73 alcoholic smokers, abstinent from alcohol and/or drugs | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 mg/day or placebo pill for 12 wks + counselling | |

| Outcomes | Cigarettes per day, stage of change | |

| Notes | Abstinence data not reported | |

°Rohsenow 2007.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Not described Design: Laboratory‐based, within‐subject design |

|

| Participants | 134 smokers, 54% F, ≥ 15 cpd, av age 49 | |

| Interventions | 3 x 3 randomised, between‐subject, parallel‐groups, crossed‐medication (naltrexone 50 mg vs placebo) + nicotine patch (42 mg vs 21 mg); cigarette cue exposure + smoking challenge | |

| Outcomes | Cue reactivity: smoking urges + withdrawal, hedonic + aversive effects of smoking | |

| Notes | ||

°Rukstalis 2005.

| Methods | NALTREXONE

Country: USA

Recruitment: Local adverts Design: Laboratory‐based, double‐blinded, within‐subject design |

|

| Participants | Smokers, ≥ 10 cpd, ≥ 18, 42% F | |

| Interventions | Lab‐based, double‐blind, within‐subject, counterbalanced, 3‐session study: 1. naltrexone 50 mg; 2. bupropion 300 mg; 3. placebo; with cigarette choice (nicotinised 0.6 mg vs denicotinised 0.05 mg cigarettes) smoking challenge |

|

| Outcomes | Smoking urges, smoking satisfaction | |

| Notes | ||

°Sutherland 1995.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: UK Recruitment: Newspaper adverts Design: Laboratory‐based, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over trial | |

| Participants | 12 heavy smokers (4 men, 8 women), ≥ 20 cpd, CO ≥ 30 | |

| Interventions | Subjects seen on 6 occasions. Sessions grouped in 2 blocks of 3 sessions. First block evaluated at baseline, during acute nicotine administration and then given naltrexone 50 mg orally or a placebo pill with trace amounts of nicotine and asked to abstain from smoking until next session 24 hours later. Then followed for 48‐hour ad lib smoking period | |

| Outcomes | Withdrawal symptoms, mood, satisfaction and other subjective measures, ad lib smoking | |

| Notes | No long‐term abstinence data reported | |

°Wewers 1998.

| Methods | NALTREXONE Country: USA Recruitment: Adverts Design: Laboratory‐based, randomised, double‐blind, repeated measures experimental design | |

| Participants | 43 smokers, > 10/day, age > 19, admitted to Clinical Research Centre for 6 days | |

| Interventions | Naltrexone 50 mg or placebo pill. 22 received naltrexone and 21 received placebo for 3 days Abstinence not attempted | |

| Outcomes | Plasma nicotine, expired air CO, number of cigarettes smoked, self‐reported satisfaction with smoking, mood and withdrawal | |

| Notes | ||

CO: Carbon monoxide; cpd: cigarettes per day; FTQ: Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire; iv: Intravenous; ITT: Intention‐to‐treat (includes all randomised); PPA: Point prevalence abstinence; ppm: parts per million; Sc: subcutaneous; wks: weeks

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ahmadi 2003 | No placebo control group, and high drop‐out rates (63 ‐ 95%). |

| Byars 2005 | No follow‐up beyond 12 wks. |

| Croop 2000 | Unpublished data not released. |

| Krishnan‐Sarin 2003 | No follow‐up beyond 4 wks. |

| O'Malley 1995 | Designed to evaluate effect on alcohol consumption and did not provide any data on tobacco consumption. |

| Roozen 2006 | Follow‐up only 3 months, no placebo group, so did not contribute data on withdrawal or other outcomes. |

| Toll 2008 | Not randomised. Follow‐up only six wks. |

| Toll 2010b | Follow‐up only 6 wks. |

| Wilcox 2010 | No placebo control group. |

Differences between protocol and review

The following changes to methods were made in the 2013 update:

Short‐term (end of treatment) abstinence was added as a secondary outcome for meta‐analysis. Studies that only report short‐term abstinence outcomes are still excluded, but short‐term outcomes were extracted for a sensitivity analysis of the effect of including them in this analysis.

Studies were not required to have biochemical validation of abstinence for inclusion (no studies had previously been excluded for this reason).

Contributions of authors

SD initiated the review, drafted the protocol, checked relevant studies, extracted data and drafted the review. LS and SD extracted data. LS and JP assisted in finalising the review. SD, LS, TL, EE and JP reviewed and approved the update for the 2013 version of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Brown University/Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, USA.

Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, UK.

National School for Health Research School for Primary Care Research, UK.

External sources

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

-

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), USA.

R01 MH083684 (Dr Prochaska)

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse, USA.

P50 DA009253 (Dr Prochaska)

-

Tobacco‐Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), USA.

17RT‐0077

Declarations of interest

Nil.

New search for studies and content updated (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

°Boureau 1978 {published data only}

- Boureau F, Willer JC. Failure of naloxone to modify the anti‐tobacco effect of acupuncture [Desintoxication tabagique par l'acupuncture: essai negatif de blocage par la naloxone]. Nouvelle Presse Médicale 1978;7(16):1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Brauer 1999 {published data only}

- Brauer LH, Behm FM, Westman EC, Patel P, Rose JE. Naltrexone blockade of nicotine effects in cigarette smokers. Psychopharmacology Berl 1999;143:339‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Caskey 2001 {published data only}

- Caskey NH, Olmstead RE, Jarvik ME, Madsen DC, Iwamoto‐Schaap PN, Terrace S, et al. The acute effects of low dose naltrexone on ad lib smoking in normal heavy smokers (PO2 77). Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 7th Annual Meeting March 23‐23 Seattle Washington. 2001:Abstracts book p106.

°Epstein 2004 {published data only}

- Epstein AM, King AC. Naltrexone attenuates behavioral and objective measures of cigarette smoking (POS1‐29). Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 9th Annual Meeting February 19‐22 New Orleans, Louisiana. 2003:Abstracts book p43.

- Epstein AM, .King AC. Naltrexone attenuates acute cigarette smoking behavior. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior 2004;77:29‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Gorelick 1988 {published data only}

- Gorelick DA, Rose JE, Jarvik ME. Effect of naloxone on cigarette smoking. Journal of Substance Abuse 1988;1:153‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Houtsmuller 1997 {published data only}

- Houtsmuller EJ, Clemmey PA, Sigler LA, Stitzer ML. Effects of naltrexone on smoking and abstinence (In: Problems of Drug Dependence 1996, Proceedings of the 58th annual Conference). Nida Research Monograph 1997;174:68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Hutchison 1999 {published data only}

- Hutchison KE, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Colby SM, Gnys M, et al. Effects of naltrexone with nicotine replacement on smoking cue reactivity: preliminary results. Psychopharmacology Berl 1999;142:139‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Karras 1980 {published data only}

- Karras A, Kane JM. Naloxone reduces cigarette smoking. Life Sciences 1980;27:1541‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°King 2000 {published data only}

- King AC, Meyer PJ. Naltrexone alteration of acute smoking response in nicotine‐dependent subjects. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior 2000;66(3):563‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Knott 2007 {published data only}

- Knott VJ, Fisher DJ. Naltrexone alteration of the nicotine‐induced EEG and mood activation in tobacco‐deprived cigarette smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2007;15(4):368‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Krishnan‐Sarin 1999 {published data only}

- Krishnan‐Sarin S, Rosen MI, O'Malley SS. Naloxone challenge in smokers. Preliminary evidence of an opioid component in nicotine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 1999;56(7):663‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Lee 2005 {published data only}

- Lee YS, Joe KH, Sohn IK, Na C, Kee BS, Chae SL. Changes of smoking behavior and serum adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, prolactin, and endogenous opioids levels in nicotine dependence after naltrexone treatment. Progress in Neuro‐psychopharmacol and Biological Psychiatry 2005;29(5):639‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na C, Ku YS, Lee YS. Smoking behavior and hormonal change after naltrexone in nicotine dependence. 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 17 22, San Francisco CA. 2003:NR694.

°Mello 1985 {published data only}

- Mello NK, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. Buprenorphine effects on cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology Berl 1985;86(4):417‐25. [PUBMED: PMID 3929312] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Mutschler 2002 {published data only}

- Mutschler NH, Stephen BJ, Teoh SK, Mendelson JH, Mello NK. An inpatient study of the effects of buprenorphine on cigarette smoking in men concurrently dependent on cocaine and opioids. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2002;4(2):223‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Nemeth‐Coslett 1986 {published data only}

- Nemeth‐Coslett R, Griffiths RR. Naloxone does not affect cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology Berl 1986;89(3):261‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°O'Malley 1998 {published data only}

- O'Malley S, Krishnan‐Sarin SS, Meandzija B. Naltrexone in the treatment of nicotine dependence: A preliminary study. Proceedings of the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting. 1997.

- O'Malley SS, Krishnan‐Sarin S, Meandzija B. Naltrexone treatment of nicotine dependence: a preliminary study. Addiction 1998;93(6):918‐9. [Google Scholar]

°Olmstead 2002 {published data only}

- Olmstead RE, Caskey NH, Madsen DC, Terrace S, Iwamoto‐Schaap PN, Griffith TM, et al. The acute effects of low dose naltrexone on ad lib smoking in normal heavy smokers and chippers. Proceedings for the Society of Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 8th Annual Meeting, Savannah GA. 2002.

°Ray 2006 {published data only}

- Ray R, Jepson C, Patterson F, Strasser A, Rukstalis M, Perkins K, Lynch KG, O'Malley S, Berrettini WH, Lerman C. Association of OPRM1 A11G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology Berl 2006;188(3):355‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Ray 2007 {published data only}

- Ray RA, Miranda R, Kahler CW, Leventhal AM, Monti PM, Swift R, et al. Pharmacological effects of naltrexone and intervenous alcohol on craving for cigarettes among light smokers: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology Berl 2007;193(4):449‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Rohsenow 2003 {published data only}

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Colby SM, Gulliver SB, Swift RM, Abrams DB. Naltrexone treatment for alcoholics: effect on cigarette smoking rates. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2003;5(2):231‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Rohsenow 2007 {published data only}

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Hutchison KE, Swift RM, MacKinnon SV, Sirota AD, et al. High‐dose transdermal nicotine and naltrexone: effects on nicotine withdrawal, urges, smoking, and effects of smoking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2007;15(1):81‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Rukstalis 2005 {published data only}

- Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Strasser A, Lynch KG, Perkins K, Patterson F, et al. Naltrexone reduces the relative reinforcing value of nicotine in a cigarette smoking choice paradigm. Psychopharmacology Berl 2005;180:41‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Sutherland 1995 {published data only}

- Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Naltrexone, smoking behaviour and cigarette withdrawal. Psychopharmacology Berl 1995;120(4):418‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

°Wewers 1998 {published data only}

- Wewers ME, Dhatt R, Tejwani GA. Naltrexone administration affects ad libitum smoking behavior. Psychopharmacology Berl 1998;140(2):185‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers ME, Dhatt RK, Tejwani GA. Naltrexone administration influences cigarette smoking behaviour. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 1999;1(1):112‐3. [Google Scholar]

Baltieri 2009 {published and unpublished data}

- Baltieri DA, Daró FR, Ribeiro PL, Andrade AG. Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction 2008;103(12):2035‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltieri DA, Daró FR, Ribeiro PL, Andrade AG. Effects of topiramate or naltrexone on tobacco use among male alcohol‐dependent outpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2009;105(1‐2):33‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Covey 1999 {published data only}

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Naltrexone effects on short‐term and long‐term smoking cessation. Journal of Addictive Diseases 1999;18:31‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Naltrexone for smoking cessation. Journal of Addictive Diseases 1996;15:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

King 2006 {published data only}

- King A, Chilton E, Niaura R, Hatsukami D. Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: effects of gender on clinical response (PA8‐6). Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 9th Annual Meeting February 19‐22 New Orleans, Louisiana. 2003:32.

- King A, Wit H, Riley RC, Cao D, Niaura R, Hatsukami D. Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: a preliminary study and an examination of sex differences. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2006;8:671‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Chilton E, Niaura R. Role of naltrexone in initial smoking cessation: preliminary findings. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 2002;26(12):1942‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

King 2012 {published data only}

- Fucito LM, Toll BA, Roos CR, King AC. Medication expectancies predict smoking cessation success. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 19th Annual Meeting March 13‐16 Boston MA. 2013:58.

- King AC, Cao D, O'Malley SS, Kranzler HR, Cai X, Dewit H, et al. Effects of naltrexone on smoking cessation outcomes and weight gain in nicotine‐dependent men and women. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2012;32(5):630‐6. [] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]