Abstract

Inducible micro RNAs (miRNAs) perform critical regulatory roles in central nervous system (CNS) development, aging, health and disease. Using miRNA arrays, RNA-sequencing, enhanced Northern dot blot hybridization technologies, Western immunoblot and bioinformatics analysis we have studied miRNA abundance and complexity in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain tissues compared to age-matched controls. In both short post-mortem AD and in stressed primary human neuronal-glial (HNG) cells we observe a consistent up-regulation of several brain-enriched miRNAs that are under transcriptional control by the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-kB. These include miRNA-9, miRNA-34a, miRNA-125b, miRNA-146a and miRNA-155. Of the inducible miRNAs in this subfamily, miRNA-125b is amongst the most abundant and significantly induced miRNA species in human brain cells and tissues. Bioinformatics analysis indicates that up-regulated miRNA-125b targeted expression of (a) the 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX; ALOX15; chr 17p13.3), utilized in the conversion of docosa-hexaneoic acid (DHA) into neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1), and (b) the vitamin D3 receptor (VDR; VD3R; chr12q13.11) of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. 15-LOX and VDR are key neuromolecular factors essential in lipid-mediated signaling, neurotrophic support, defense against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS) and neuroprotection in the CNS. Pathogenic effects appear to be mediated via specific interaction of miRNA-125b with the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of the 15-LOX and VDR messenger RNAs (mRNAs). In AD hippocampal CA1 and in stressed HNG cells, 15-LOX and VDR down-regulation and a deficiency in neurotrophic support, may therefore be explained by the actions of a single inducible, pro-inflammatory miRNA-125b. We will review recent data on the pathogenic actions of this up-regulated miRNA-125b in AD, and discuss potential therapeutic approaches using either anti-NF-kB or anti-miRNA-125b strategies. These may be of clinical relevance in the restoration of 15-LOX and VDR expression back to control levels and the re-establishment of homeostatic neurotrophic signaling in the CNS.

Keywords: 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), innate immune response, micro RNA (miRNA), miRNA-125b, ncRNA, neuro-inflammation, neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1), vitamin D receptor (VDR)

Introduction

Micro RNA (miRNA)

Single-stranded nucleic acids known as microRNAs (miRNAs) represent an evolutionarily conserved class of RNA polymerase II or III (RNA Pol II, RNA Pol III) generated 21-23 nucleotide, small non-coding RNAs (snRNAs) involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. While our understanding on the neurobiological mechanism and relevance of miRNA signaling continues to evolve, it is currently widely accepted that the major mode of miRNA action is to regulate gene expression through an imperfect base-pairing with the 3′ un-translated region (3′-UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and depending on this sequence complementarity within an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), results in either reduction or inhibition in the translation of the target mRNA, and hence the down-regulation in the expression of that mRNA’s genetic information [1-6]. Up-regulated mammalian miRNAs therefore, predominantly act to decrease their target mRNA levels, and down-regulated miRNAs may be a reflection of post-mortem artifacts due to rapid miRNA decay, especially in the analysis of human post-mortem brain tissues [5-10]. While the potential contribution of snRNA to the regulation of brain gene function has been known for over 20 years [11], more recently there has been an explosion into molecular-genetic and epigenetic research involving the neurobiological function of these snRNAs in brain development, aging, health, acute injury and chronic disease [2,12-18]. To date virtually all CNS metabolic, neurochemical, endocrine and signaling processes that are reliant on mRNA-based gene expression are now known to involve direct modulation by CNS miRNAs. The focus of this review will be the miRNA-125b-mediated down-regulation in the expression of 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in AD and in related models of progressive, age-related inflammatory degeneration of the human CNS.

miRNA and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

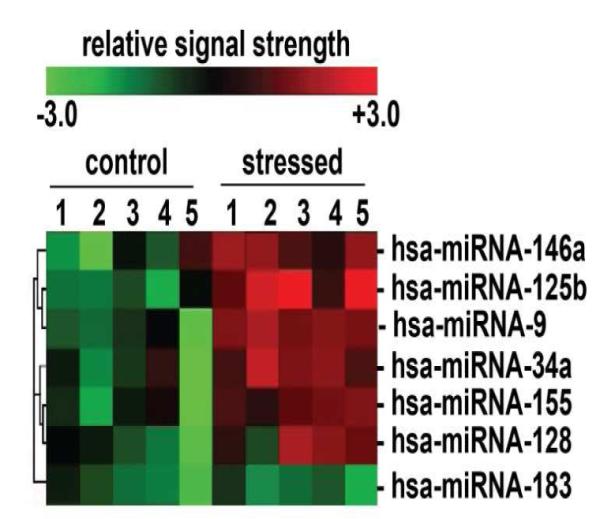

Many laboratories have independently analyzed miRNA abundance, speciation and complexity in various anatomically-relevant regions of the AD brain at various stages of AD, and in modeling systems such as those employing human brain cells stressed with AD-relevant stressors, including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), the 42 amino acid amyloid beta (Aβ42) peptide, neurotrophic viruses such as herpes simplex-1 (HSV1), and neurotoxic, environmentally abundant, ROS-generating metal sulfates [1-15]. Resulting patterns of miRNA expression have been analyzed using DNA arrays, miRNA arrays, RNA-sequencing, Northern dot blot hybridization technologies, ELISA, Western immunoblot and bioinformatics analysis [12-18]. No clear ‘universal’ consensus on what miRNAs are specifically altered in abundance in AD has emerged to date, and this may be a reflection of a number of factors including (a) the initial accuracy of the diagnosis of AD; (b) the drug and medication history of the AD patient, and selection of controls; (c) post-mortem and brain-freezing or tissue-storage effects; (d) problems associated with tissue acquisition and processing, pre-mortem, agonal, and concurrent disease effects; (e) the type of analytical techniques used; (f) methods of bioinformatics analysis; (g) the anatomical region of the brain analyzed, and (h) intrinsic human genetic, epigenetic and biochemical individuality [7,8,19,20]. A genuine concern of using post-mortem tissues are that miRNAs are rapidly degraded so a down-regulated miRNA may be, in part, a reflection enhanced miRNA decay, especially in long postmortem delay pathological tissues [5-10]. Differential miRNA abundances in AD may also be an indication of differential gene expression patterns between individuals, sometimes referred to as ‘human biochemical and genetic individuality’; such variability might have bearing on an individual’s susceptibility to AD onset, development and disease course [15-23]. For example, one recent study showed that African Americans, who in general appear to be more susceptible to AD and exhibit a more intense clinical course, also had significant increases in specific miRNAs in their brains when examined post-mortem, including up-regulated miRNAs known to drive critical aspects of AD pathology [20]. Alexandrov et al’s rigorous analysis of carefully controlled very short post-mortem interval AD brains, extracellular fluid (ECF) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed that a selective subset of miRNAs that includes miRNA-9, miRNA-34a, miRNA-125b, miRNA-146a and miRNA-155 are significantly increased in AD brain hippocampal CA1, temporal lobe neocortex, ECF and CSF, and that these same miRNAs are also induced in human brain cells in primary culture when stressed with AD-relevant stressors (Figure 1) [21-23]. AD-relevant stressors include pro-inflammatory cytokines and neurotoxic peptides known to be overly abundant in AD affected brain cells and tissues, and these include the CNS-resident cytokines IL-1β, TNFα, Aβ42 peptides, or complex mixtures of these noxious reagents. AD-relevant stressors also include neurotrophic viruses such as HSV-1 and the ubiquitous, environmentally abundant neurotoxin aluminum [6,13]. Interestingly, the up-regulated miRNAs that in turn down-regulate their mRNA targets is in line with the progressive down-regulation of gene expression as is observed by multiple laboratories in the AD brain [24-27]. Another notable point is that this quintet of up-regulated miRNA is under transcriptional regulatory control by RNAP II and the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-kB [28-31]. NF-kB has long been known to exhibit a generalized up-regulation in AD brain tissues and in other neurological diseases with a progressive, inflammatory, neurodegenerative component [28-30]. As discussed further below, anti-NF-kB strategies have been shown in vitro to effectively quench pathogenic miRNA induction; the extrapolation of these NF-kB-inhibitory techniques to animal models awaits further investigation, as does translation and the potential use of NF-kB inhibitors directed towards the clinical management of AD [31].

Figure 1. Up-regulated AD-relevant miRNAs regulated by NF-kB.

primary HNG cells were treated with an AD-relevant, NF-kB-inducing cocktail of Aβ42 peptide (5 M; Sigma-Aldrich) plus human recombinant interleukin-1β (IL-1β; 10 nM; I4019, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO); Aβ42 peptides were prepared using the hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) evaporation-dimethyl sulfoxide-solubilization method as previously described [10,39,40]. Confirmation of selective miRNA induction and NF-kB sensitivity was obtained using (a) RNA sequencing; (b) LED-Northern dot blot and/or (c) RT-PCR analysis [10,39]; (d) by inhibition of this induction using specific NF-kB inhibitors CAPE, CAY10512 and PDTC [10,39,64] and (e) by bioinformatics analysis of functional NF-kB binding sites in the promoters of the genes that encode these inducible miRNAs [10,39,60]. A small family of 5 miRNAs including miRNA-9, miRNA-34a, miRNA-125b, miRNA-146a and miRNA-155 were found to be up-regulated in both stressed HNG cells and in high quality total RNA isolated from short post-mortem AD brain; note that hsamiRNA-128 is an example of a variably up-regulated miRNA; miRNA-183 is an internal control miRNA that is neither up- nor down-regulated after induced stress; N=5; other up-regulated miRNAs showed modest up-regulation but are not discussed further here [10,39,64].

Inducible, NF-kB-sensitive miRNA expression

Because the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-kB has been reported to be overly abundant in AD affected tissues and is in general an extremely potent pro-inflammatory gene activator [28-31], it was perplexing to formulate a hypothetical mechanism why so many brain-essential genes have been found to be down-regulated in sporadic AD tissues by several independent investigators [24-27]. Indeed, roughly 2/3 of all expressed genes are observed to be down-regulated in the hippocampal CA1, superior temporal neocortex or other neocortical regions in moderate-to-advanced sporadic AD [24-27]. A hypothesis was formulated that NF-kB activates the transcription of several relatively abundant miRNAs, including miRNA-125b [28-31], and the up-regulation of this miRNA subfamily is ultimately responsible for the down-regulation of brain essential genes as is observed not only in sporadic AD tissues but also in AD cell culture models undergoing AD-relevant stress [10,13,15]. Indeed, pro-inflammatory cytokines and peptides such as IL-1β, TNFα, Aβ42 peptides, as well as HSV-1 and aluminum, are potent activators of both NF-kB and perhaps not too surprisingly NF-kB-sensitive miRNAs [6,13,28-32].

Up-regulated miRNA-125b has multiple pathogenic effects

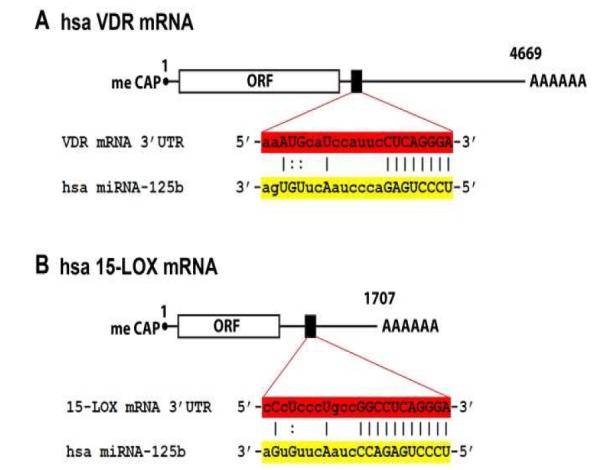

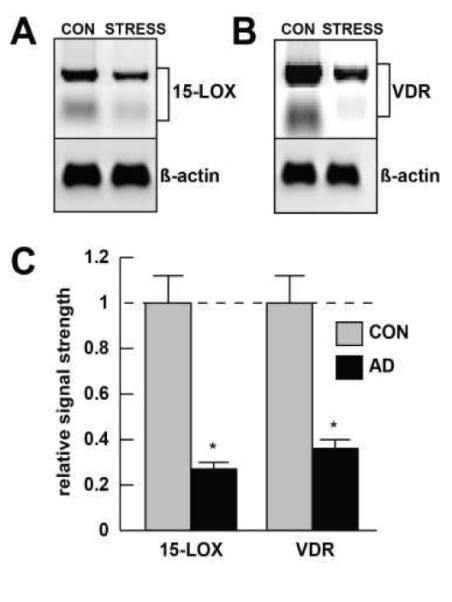

Of the up-regulated miRNAs observed in AD tissues and in stressed human primary brain cells, miRNA-125b is an extremely abundant and inducible snRNA that is under transcriptional control by NF-kB [30-32]. Up-regulated miRNA-125b has been shown to target and down-regulate many phagocytic-, synaptogenic- and neurotrophism-relevant genes [38-40,69-72]. These include decreased expression of 15-LOX and VDR, by virtue of miRNA-125b recognition features in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTRs) of target 15-LOX and VDR mRNAs; Figure 2; see below). The result of miRNA-125b up-regulation and targeting such selective gene expression systems and AD-relevant neurological targets is further associated with multiple neurological dysfunctions including hypoxic-ischemic brain damage [33], astrogliosis in sporadic AD [34] and glial cell proliferation, both in AD and in glioma and glioblastoma [35]. Interestingly 15-LOX and VDR are significantly down-regulated in [Aβ42+IL-1β]-stressed HNG cells (Figure 3). Another miRNA-125b related, early event in AD appears to be the miRNA-125b-mediated down-regulation of complement factor H (CFH), a key repressor protein in complement activation and the innate immune response of the brain [36]. In this mechanism miRNA-125b appears to act alone or in concert with other NF-kB-sensitive, pro-inflammatory miRNAs to stimulate a pathogenic pro-inflammatory response [36,40]. Progressive miRNA-125b-mediated down-regulation of CFH has been shown to occur in AD brain hippocampal CA1 and the superior temporal lobe neocortex, and correlate with an enhancement in pro-inflammatory signaling and disruption of the innate-immune response of the aging AD brain [37-40]. The abundance and ubiquity of miRNA-125b up-regulation in AD brain tissues and in stressed HNG cells may be particularly significant because this pro-inflammatory miRNA is also abundant in AD-derived extracellular fluid (ECF) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), suggesting paracrine signaling capabilities and potential for spreading miRNA-125b-mediated neuropathology throughout the CNS.

Figure 2. Complementarity maps between homo sapiens VDR or 15-LOX mRNA 3′-UTRs and miRNA-125b.

[A] schematic representation of human VDR mRNA, highlighting a section (black box) of the 3′-untranlated region (3′-UTR) and the complementarity of this VDR mRNA 3′-UTR region (red) with the predicted target sequence of homo sapien (hsa) miRNA-125b (yellow); size and scale are approximate; the human VDR mRNA (encoded from a 9 exon gene at chr12q13.11; GenBank: AB002168.2)contains about 4669 nucleotides followed by a variable poly A tail [50; http://www.Genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=VDR; Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel]; meCAP = 5′ methyl cap typical of all eukaryotic mRNAs and ORF = open reading frame; the numbering refers to the 5′ end of the mRNA as 1; a ‘:’ indicates a partial hydrogen bond and an ‘I; indicates a perfectly complementary hydrogen bond; ribonucleotides in upper case are implicated in either partial or full hydrogen bonding; [B] is a schematic representation of human 15-LOX (ALOX15; arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase) mRNA, highlighting a section of the 3′-UTR (black box) and the complementarity of this 15-LOX mRNA 3′-UTR region (red) with the predicted target sequence of hsa miRNA-125b (yellow); the hsa 15-LOX mRNA (encoded by a 14 exon gene at chr 17p13.3; GenBank: U88317.1) is considerably smaller than the hsa VDR mRNA; size and scale are approximate; the human 15-LOX mRNA contains about 1707 nucleotides followed by a variable poly A tail [see http://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=ALOX15&search=15-lox.

Figure 3. As in AD brain, 15-LOX and VDR expression is down-regulated in stressed HNG cells.

Western analysis; HNG cells were cultured as previously described in detail [10,40,47,67,72]. An AD-relevant stress cocktail of [Aβ42+IL-1β] together was found to reduce 15-LOX [A] and VDR [B] protein levels to approximately 0.25- and 0.35-fold, respectively, of their control, homeostatic levels in these HNG cell co-cultures [10,40,67]; human antibodies for 15-LOX and VDR were respectively [(C-20): sc-1008] and [(H235); sc-32940; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA; www.scbt.com); Western analysis yielded 2 bands for both 15-LOX (~80 and ~75 kDa) and VDR (~48 and ~56 kDa); both bands were quantitated for the bar graph in [C]; the reductions in both 15-LOX and VDR in stressed HNG cells compared to untreated control are highly significant compared to an unchanging β-actin signal in the same sample; N=4, *p<0.01 (ANOVA); a dashed horizontal line at 1.0 indicates control, homeostatic levels for 15-LOX (left panel) and VDR (right panel) for ease of comparison.

miRNA-125b is up-regulated in AD ECF and CSF

Besides variations in specific miRNA abundance in AD cells and tissues, several independent research groups have identified potentially pathogenic miRNAs in human extracellular fluid (ECF; the interstitial fluid that surrounds brain cells), CSF, blood serum and other secreted bodily fluids, underscoring their potential for paracrine effects and the potential transmission of disease-carrying ribonucleic acid signals [15,20,21]. Importantly, miRNA-125b is very highly expressed in brain anatomical regions including the entorhinal neocortex and hippocampal CA1 where AD is thought to originate, in the ECF that surrounds hippocampal and neocortical brain cells, in the CSF that circulates throughout the CNS, and in the plasma of patients suffering from AD and other neurological disorders such as spinocerebellar ataxia type 3/Machado-Joseph disease (SCA3/MJD) and human prion diseases [15,20,32,34,41-43]

miRNA-125b and AD-relevant targets involved in neurotrophism

15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) and the DHA-NPD1 conversion

The lipoxygenase (LOX) enzymes represent a small family of iron-containing, membrane-peripheral or membrane-integral proteins which dioxygenate unsaturated fatty acids, thus (a) initiating the synthesis of membrane-derived signaling molecules; (b) inducing membrane-structural and cellular metabolic changes; and (c) supporting the lipoperoxidation of membranes [45-48]. Brain- and retinal-abundant LOX enzymes in mammals include 5-LOX (EC 1.13.11.34), 12-LOX (EC 1.13.11.31), and 15-LOX (EC 1.13.11.33), classified with respect to their positional specificity of the deoxygenation of their primary substrate arachidonic acid (AA). The lipoxygenases also utilize other unsaturated fatty acid as primary substrates and these include docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [47-49].

Age-related deficiencies in the abundance of DHA, normally a major component of brain and retinal phospholipids and an essential omega-3 fatty acid required for brain and retinal development and health, is significantly associated with cognitive decline in AD and retinal dysfunction in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Multiple studies indicate that lipid peroxidation targets phospholipids containing highly unsaturated fatty acids such as DHA, and the DHA content in AD brain is significantly reduced [47,48]. Normally, a novel DHA-derived, anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective 10,17S-docosatriene known as neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1) is generated from unesterified DHA via the action of a 15-LOX [46,47]. Several studies have shown that increases in the abundance of miRNA-125b in AD brain tissues is associated with decreased 15-LOX expression and decreased abundance of NPD1 (Figure 3, Figure 4) [44-47]. Hence miRNA-125-mediated decreases in 15-LOX and deficits in DHA-derived NPD1 may attenuate homeostatic anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective gene expression programs that normally modulate anti-inflammatory signaling and promote brain and retinal cell survival. Interestingly 15-LOX, acting as a key agent in phospholipid metabolism and physiological membrane remodeling has been further implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, inflammation, immune tolerance and carcinogenesis [46-49].

Figure 4.

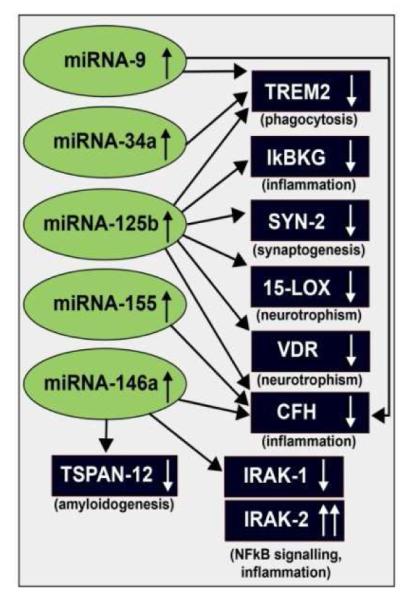

Taken together, recent findings define in part a highly interactive network of NF-kB-sensitive, up-regulated miRNAs in stressed human brain cells and AD brain that can explain much of the observed neuropathology in AD. The CNS-abundant, miRNA-125b is a central member of this up-regulated miRNA group that may be in part responsible for driving deficits in phagocytosis (TREM2), innate-immune signaling and chronic inflammation (IkBKG, CFH), impairments in neurotransmitter packaging and release (SYN-2), and neurotrophism (15-LOX, VDR). Other NF-kB-sensitive up-regulated miRNAs (such as miRNA-146a) appear to be responsible for the observed deficits in NF-kB regulation (IRAK-1, IRAK-2) and/or amyloidogenesis (TSPAN12) (see text); these up-regulated miRNAs and down-regulated mRNAs form a highly integrated, pathogenic miRNA-mRNA signaling network resulting in gene expression deficits in sporadic AD that may be self-perpetuating due to chronic re-activation of NF-kB stimulation perhaps through the involvement of deficits in IkBKG signaling [10,73-76]. Inhibition of the NF-kB initiator or individual blocking of the pathogenic induction of these 5 miRNAs may provide novel therapeutic approaches for the clinical management of AD, however what NF-kB or miRNA inhibition strategies, or whether they can be utilized either alone or in combination, remain open to experimentation (see Figure 4). Extensive recent data in human brain cells in primary culture has indicated that these approaches may neutralize this chronic, inducible, progressive pathogenic gene expression program to re-establish brain cell homeostasis, and ultimately be of novel pharmacological use in the clinical management of AD.

Vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor (VDR)

Collectively, cell culture, animal modeling and clinical data support the idea that 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 [1,25-(OH)2D3; cholecalciferol; vitamin D3] and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) performs critical roles in brain cell detoxification, differentiation, inflammation, neuroplasticity neuroprotection, neurotransmission and prominently, neurotrophism [50-62]. The VDR is co-localized to both neurons and astroglia, and enzymes linked to vitamin D metabolism, including vitamin D-dependent synthesis of neurotrophic factors and neurotransmitters that are highly expressed in the CNS, including dopamine and serotonin, influence neurotransmitter systems implicated in behavior, mood, motivation, and memory [54-56]. Neuroprotective and immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D and the VDR have been described in several experimental models, indicating the potential value of this essential, fat-soluble lipophilic hormone and its pharmacological analogs in the treatment of neurodegenerative and neuroimmune diseases that include AD [50-56]. Interestingly, vitamin D has shown benefit in clinical trials for AMD and the combination of memantine and vitamin D significantly prevents axon degeneration induced by amyloid-beta and glutamate, a proposed underlying contributory mechanism to the AD process [58,59]. Very recent clinical trials involving DHA and vitamin D have demonstrated considerable therapeutic potential for cancer, cardiovascular disease, epilepsy and neurodegenerative disorders [60-62].

Neurobiological actions of vitamin D are regulated through the VDR (also known as the calcitriol receptor or NR1I1; nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group I, member 1) and represents a prominent member of the superfamily of nuclear steroid hormone receptors [51-55]. Upon complexation with vitamin D, the VDR forms a heterotypic dimer with the retinoid-X receptor that subsequently binds tovitamin D responsive elements (VDREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes throughout the genome, with this multimeric complex functioning as a trans-acting transcriptional activation factor [50-62]. Yokoi’s group and others have demonstrated that the VDR expression is under regulatory control by miRNA-125b, and up-regulated miRNA-125b drives the down-regulation of the VDR via a productive miRNA-125b-VDR mRNA-3′-UTR interaction (Figure 1) [50]. As for 15-LOX protein, VDR protein abundance is down-regulated in stressed human brain cells (Figure 3) and in AD (unpublished observations). Interestingly, loss-of-function polymorphisms in the VDR gene are linked to increased incidence of AD in several independent studies [50-54]. The miRNA-125b-mediated regulation of VDR expression underscores that nuclear receptors to which brain hormones, such as vitamin D, bind as a ligand, may be critically regulated by miRNAs, culminating in changes in nuclear receptor sensitivity and the down-regulated expression of a variety of VDR-associated target genes in complex miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks in the brain and retina [62-72].

Other disease-relevant miRNA-125b-mRNA targets

Due in part to the ubiquity of miRNA-125b abundance in the brain it is perhaps not too surprising that miRNA-125b up-regulation has been shown to be involved, in part, in the down-regulated expression of an important family of brain-essential genes. These include the miRNA-125-mediated down-regulation of (a) the triggering receptor for expression in microglial/myeloid cells (TREM2) essential in amyloid peptide phagocytosis; (b) the NF-kB essential modulator (NEMO) also known as inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit gamma (IKK-γ) encoded by the IKBKG gene; (c) the synaptic vesicle phosphoprotein synapsin-2 (SYN-2), a key modulator of neurotransmitter release across the pre-synaptic membrane; (d) a 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) involved in the conversion of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to the highly neurotrohic neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1); (e) the nuclear steroid hormone VDR; and (f) the innate-immune-regulatory protein complement factor H (CFH) (Figure 4) [10,39,69-72]. Interestingly, because miRNA-125b is inducible, and under strong transcriptional control by NF-kB, it might be predicted that any disease-associated biophysical or physiological stressor that activates NF-kB in the cell (see below) may also activate miRNA-125b, the select mRNA family that miRNA-125b targets, and their subsequent pathology-associated effects. These actions may be amenable to pharmacological intervention using either anti-NF-kB and/or anti-miRNA-125b therapeutic strategies (Figure 5).

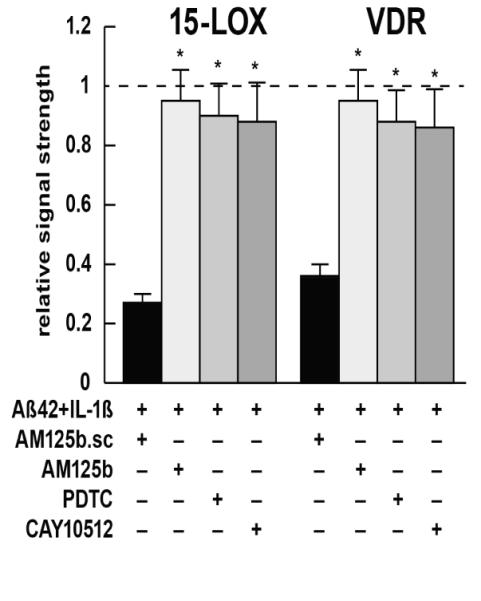

Figure 5. Western analysis; recovery of 15-LOX and VDR expression using anti-miRNA-125b or anti-NF-kB treatment strategies in vitro.

AD-relevant stress (a cocktail of Aβ42+IL-1β; see Figure 1) reduces 15-LOX and VDR protein levels to respectively 0.25- and 0.35-fold of their control, homeostatic levels in primary HNG cell co-cultures [10,40,67]; while a control scrambled anti-miRNA-125b (AM125b.sc) has no effect on restoring protein levels (black bars), a fully antisense, protected anti-miRNA-125b (AM125b; light gray bars) restores expression levels to near control levels; for ease of comparison a dashed horizontal line at 1.0 indicates pre-stress (control) levels for 15-LOX and VDR; similarly the NF-kB inhibitors pyrollidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC; medium gray bars) and the polyphenolic resveratrol analog trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxy-stilbene CAY10512 (dark gray bars) [10,39,40] show near equal restoration of 15-LOX and VDR signals back to homeostatic (control) levels; these data and recently published data indicate that anti-miRNA (AM, antagomir) and/or anti-NF-kB therapeutic strategies may be useful in restoring homeostatic gene expression in AD; N=3; *p<0.01 (ANOVA); see also text and Figures 1 and 3.

Anti-NF-kB versus anti-miRNA-125b strategies

As research into human miRNA speciation, complexity and biological activity continues to progress, it has emerged that highly selective subsets of all so-far-characterized miRNAs utilized by human cells and tissues are under complex RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) or RNA Pol III transcriptional control, just as are the transcription of protein-encoding mRNAs. As fore-mentioned, miRNA-125b is just one prominent member of a highly selected, miRNA subset under inducible transcriptional control by the pro-inflammatory and immune system-linked transcription factor NF-kB [39,40]. This ubiquitously expressed pro-inflammatory transcription factor is comprised by a ~20-member family of heterodimeric DNA-binding proteins, including the relatively common p50-p65 complex, that normally resides in a ‘resting state’ in the cytoplasm [73-76]. The kinetics of the induction of NF-kB-sensitive pro-inflammatory miRNAs by each of these ~20 NF-kB family members is currently incompletely understood, but they might be expected to be highly relevant in inflammatory and immune signaling in the CNS in health and disease. Cellular NF-kB p50-p65 activation via phosphorylation of the NF-kB inhibitor IkB is stimulated by wide array of AD-relevant physiological stressors including pathogenic elevations in inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, Aβ42 peptides, hypoxia, ionizing radiation, viral infection, neurotoxic metal sulfates, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS) and other AD-relevant stressors that are associated with diet, lifestyle and environmental factors [6,13,63-67]. The inducible up-regulation of the NF-kB-sensitive miRNA-125b is by virtue of multiple, NF-kB-DNA binding, and other recognition sites located in the transcriptional regulatory regions of the miRNA-125b (chr 11q24.1) [10,30,31,68]. In progressive neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and AMD, stress-triggered up-regulation of these NF-kB-induced miRNAs appear to be playing pathogenic roles in the down-regulation of brain-essential mRNAs, and the initiation and propagation of pathological gene expression that coincide with the disease process [30,31]. NF-kB-mediated up-regulated miRNAs and down-regulated mRNA targets thereby form a highly integrated, pathogenic NFkB-miRNA-mRNA signaling network that can explain much of the observed neuropathology in progressive, inflammatory brain degenerations such as AD. These collectively include deficits in phagocytosis [69,72], synaptogenesis [28-31,68], amyloidogenesis [71-75], NF-kB-mediated innate-immune signaling and chronic inflammation [39,70], impairments in neurotransmitter packaging and release, and deficits in neurotrophic signaling (Figure 4) [71,73-75]. The selective inhibition of the gene regulatory actions of NF-kB and specific NF-kB-sensitive miRNAs therefore seems a reasonable therapeutic strategy towards neutralizing their combined and integrated effects in progressive, age-related neurological diseases with an innate-immune and inflammatory component.

Ever since NF-kB’s original description in 1986, several hundred NF-kB inhibitors, both natural and synthetic, have been developed to inhibit various aspects of NF-kB-mediated gene activation in this complex signaling network [73-76]. However, constitutive NF-kB signaling is also homeostatic to many aspects of normal brain function, and essential to the control of cell proliferation, apoptosis, innate and adaptive immunity, the chronic inflammatory, and related stress response [72-74]. NF-kB activation is also an important part of a cellular recovery process that may protect brain cells against ROS, RNS or brain trauma-induced apoptosis and induced neurodegeneration, hence antagonism of NF-kB may reduce an intrinsic potential for neuroprotective activity in brain cells [72-76]. Put another way, NF-kB-inhibition strategies may be maximized only when NF-kB-stimulated effects have surpassed a critical threshold that are together seriously detrimental to the normal homeostatic function of CNS cells and tissues. It is still problematic and pharmacologically difficult to minimize the complicating effects of NF-kB inhibition on essential, low-level homeostatic NF-kB function and undesired off-target effects [76].

Anti-miRNA (AM, antagomir) approaches on the other hand appear to be much more target-efficient, and a stabilized single stranded, anti-miRNA ribonucleotide with sequence 100% homologous complementary to the target miRNA will inhibit that target miRNA with extremely high efficacy, including miRNA-125b and its 15-LOX and VDR mRNA 3′-UTR targets (Figure 4, Figure 5) [37-40]. The introduction of imperfections into base-pair complementarity between the anti-miRNA ribonucleotides and the target pathogenic miRNA results in only a partial inhibition of the miRNA with a tailored ‘throttle-down’ of miRNA-mediated effects, and could be used as a therapeutic strategy of ‘variable efficacy’ [31,36-40,63-68,72]. Interestingly, it has recently been shown that miRNAs may also target and regulate other non-coding RNAs including non-canonical targets [77,78]. It is becoming increasingly clear that the appropriate clinical application of these anti-NF-kB or anti-miRNA strategies requires a more intimate understanding of the specific NF-kB and miRNA mechanisms responsible for their activation pathway in different CNS cell types, definition of the optimal point of intervention in the NF-kB or miRNA activation pathway, and the characterization of potent and specific inhibitors of the chosen NF-kB or miRNA targets including an evaluation of undesired off-target effects. The differential pharmacological utilization of either anti-NF-kB or anti-miRNA each has its own merits and detriments, and has been the subject of several recent more in depth papers and focused reviews [28-31, 73-76].

Summary

AD is currently the most prevalent age-related neurodegenerative disease in our society, representing the leading cause of progressive cognitive decline, intellectual impairment and memory loss in our aging population. To date no effective pharmacological therapy is available to prevent, delay or cure this insidious, multifactorial brain disease. miRNAs are an evolutionarily conserved class of endogenous snRNAs that participate in the regulation of almost every disease process so far investigated, and inducible, up-regulation of their expression has a profound effect on the down-regulation of their target mRNAs, and hence the expression of the genetic information contained within those mRNAs. The complex network of miRNA signaling and the regulatory potential of miRNA families in the CNS in development, aging, health and disease are just beginning to become understood, and appreciated in its depth and scope. Novel epigenetic approaches for AD, including anti-NF-kB or anti-miRNA strategies may be useful as an efficacious AD treatment strategy. Abundant miRNAs, such as miRNA-125b, in the ECF, CSF and blood plasma suggests that genetic regulatory information carried by miRNAs might be spread to other cells and tissues of the CNS by cerebrospinal, cerebrovascular and systemic circulatory routes. Attenuation of miRNA signals from these bodily fluids, either by preventing their initial generation using anti-NF-kB strategies or by using anti-miRNA approaches may be useful for stemming the spread of AD-relevant signals and the attenuation of progressive inflammatory neurodegenerative disease, even if an effective cure for AD cannot be found. Lastly, our comprehensive understanding of neurodegeneration, memory loss and intellectual impairment will not be achievable without elucidating the role of miRNAs in non-neuronal cells such as microglia, endothelial cells that line the cerebrovasculature, and other CNS cell types that contribute to the structure, function and complex signaling intricacies of the neurovascular unit [80,81]. This may be especially important because pro-inflammatory miRNAs such as miRNA-125b appear to carry unique pathogenetic signaling information across plasma membrane and cellular barriers to drive AD-type pathology in adjacent brain cell types.

Acknowledgments

This work was originally presented at the joint meeting of the ISN-ASN in the Satellite Symposium entitled ‘Unveiling the Significance of Lipid Signaling in Neurodegeneration and Neuroprotection’ April 17-19, 2013, Cancun, MEXICO and at the Alzheimer Association International Conference 2013 (AAIC 2013), Boston MA, USA July 13-18, 2013. Sincere thanks are extended to E. Head, M. Ball, W. Poon, F. Culicchia, C. Eicken and C. Hebel for short post-mortem interval (PMI) human brain tissues or extracts, miRNA array work and initial data interpretation, and to D Guillot and AI Pogue for expert technical assistance. Thanks are also extended to the many physicians and neuropathologists who have provided high quality, short PMI human brain tissues for study; additional human temporal lobe and hippocampal CA1 control and AD brain tissues were provided by the Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders (MIND) Institute and the University of California, Irvine Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (UCI-ADRC; NIA P50 AG16573). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Research in the Lukiw laboratory involving small non-coding RNA (sncRNA), miRNA, the innate-immune response, amyloidogenesis and neuro-inflammation in AD, prion disease and AMD was supported through a COBRE III Project, a Translational Research Initiative Grant (LSUHSC), the Louisiana Biotechnology Research Network (LBRN), an Alzheimer Association Investigator-Initiated Research Grant IIRG-09-131729, and NIH NIA Grants AG18031 and AG038834.

References

- [1].Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Perron MP, Provost P. Protein components of the microRNA pathway and human diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;487:369–385. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-547-7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lukiw WJ. Micro-RNA speciation in fetal, adult and Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2007;18:297–300. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280148e8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Taft RJ, Pang KC, Mercer TR, Dinger M, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. J Pathol. 2010;220:126–139. doi: 10.1002/path.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–40. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lukiw WJ, Pogue AI. Induction of specific micro RNA (miRNA) species by ROS-generating metal sulfates in primary human brain cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sethi P, Lukiw WJ. Micro-RNA abundance and stability in human brain: specific alterations in Alzheimer’s disease temporal lobe neocortex. Neurosci Lett. 2009;459:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Noncoding RNAs and RNA editing in brain development, functional diversification and neurological disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:799–823. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rüegger S, Großhans H. MicroRNA turnover: when, how, and why. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:436–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cui JG, Li YY, Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. Differential regulation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK-1) and IRAK-2 by miRNA-146a and NF-kB in stressed human astroglial cells and in Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38951–38960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lukiw WJ, Handley P, Wong L, McLachlan DRC. BC200 and other small RNAs RNA in normal human neocortex, non-Alzheimer dementia (NAD), and senile dementia of the Alzheimer type (AD) Neurochem Res. 1992;17:591–597. doi: 10.1007/BF00968788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tsitsiou E, Lindsay MA. microRNAs and the immune response. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Yuan LY, Bhattacharjee PS, Corkern M, Clement C, et al. Acyclovir or Aβ42 peptides attenuate HSV-1-induced miRNA-146a levels in human primary brain cells. Neuroreport. 2010;21:922–927. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833da51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Madathil SK, Nelson PT, Saatman KE, Wilfred BR. MicroRNAs in CNS injury: potential roles and therapeutic implications. Bioessays. 2011;33:21–26. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Alexandrov PN, Dua P, Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. microRNA (miRNA) speciation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and extracellular fluid (ECF) Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:365–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hulse AM, Cai JJ. Genetic variants contribute to gene expression variability. Genetics. 2013;193:95–108. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cowley MJ, Cotsapas CJ, Williams RB, Chan EK, Pulvers JN, Liu MY, Luo OJ, Nott DJ, Little PF. Intra- and inter-individual genetic differences in gene expression. Mamm Genome. 2009;20:281–295. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9181-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Olson MV. Human genetic individuality. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2012;13:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090711-163825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hébert SS, Nelson PT. Studying microRNAs in the brain: technical lessons learned from the first ten years. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lukiw WJ. Variability in micro RNA (miRNA) abundance, speciation and complexity amongst different human populations and potential relevance to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:133–136. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen X, Liang H, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Secreted microRNAs: a new form of intercellular communication. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Raj A, Rifkin SA, Andersen E, van Oudenaarden A. Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature. 2010;463:913–918. doi: 10.1038/nature08781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zheng W, Gianoulis TA, Karczewski KJ, Zhao H, Snyder M. Regulatory variation within and between species. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:327–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Loring JF, Wen X, Lee JM, Seilhamer J, Somogyi R. A gene expression profile of Alzheimer’s disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:683–695. doi: 10.1089/10445490152717541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Colangelo V, Schurr J, Ball MJ, Pelaez RP, Lukiw WJ. Gene expression profiling of 12633 genes in Alzheimer hippocampal CA1: transcription and neurotrophic factor down-regulation and up-regulation of apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:462–473. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lukiw WJ. Gene expression profiling in fetal, aged, and Alzheimer hippocampus: a continuum of stress-related signaling. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:1287–1297. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000023615.89699.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ginsberg SD, Alldred MJ, Che S. Gene expression levels assessed by CA1 pyramidal neuron and regional hippocampal dissections in Alzheimer’sdisease. Neurobiol.Dis. 2012;45:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappaB in the nervous system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001271. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Strong NF-kB-DNA binding parallels cyclooxygenase-2 gene transcription in aging and in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease superior temporal lobe neocortex. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:583–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980901)53:5<583::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lukiw WJ. NF-κB-regulated, proinflammatory miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:47–52. doi: 10.1186/alzrt150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lukiw WJ. Antagonism of NF-kB-up-regulated micro RNAs (miRNAs) in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-anti-NF-κB vs. anti-miRNA strategies. Front Genet. 2013;4:77. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lukiw WJ, Andreeva TV, Grigorenko AP, Rogaev EI. Studying micro RNA function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Genet. 2012;3:327–340. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Peng T, Jia YJ, Wen QQ, Guan WJ, Zhao EY, Zhang BA. Expression of microRNA in neonatal rats with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2010;12:373–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pogue AI, Cui JG, Li YY, Zhao Y, Culicchia F, Lukiw WJ. Micro RNA-125b (miRNA-125b) function in astrogliosis and glial cell proliferation. Neurosci Lett. 2010;476:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wan Y, Fei XF, Wang ZM, Jiang DY, Chen HC, Yang J, Shi L, Huang Q. Expression of miR-125b in the new, highly invasive glioma stem cell and progenitor cell line SU3. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31:207–14. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lukiw WJ, Alexandrov PN. Regulation of complement factor H (CFH) by multiple miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Yuan LY, Bhattacharjee PS, Corkern M, Clement C, Kammerman EM, Ball MJ, Zhao Y, Sullivan PM, Hill JM. Acyclovir or Aβ42 peptides attenuate HSV-1-induced miRNA-146a levels in human primary brain cells. Neuroreport. 2010;21:922–927. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833da51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lukiw WJ, Surjyadipta B, Dua P, Alexandrov PN. Common micro RNAs (miRNAs) target complement factor H (CFH) regulation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:105–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lukiw WJ. NF-κB-regulated micro RNAs (miRNAs) in primary human brain cells. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lukiw WJ, Zhao Y, Cui JG. An NF-kB-sensitive micro RNA-146a-mediated inflammatory circuit in Alzheimer disease and in stressed human neural cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31315–31322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805371200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nelson PT, Dimayuga J, Wilfred BR. microRNA in situ hybridization in the human entorhinal and transentorhinal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:7–11. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.007.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Le MT, Xie H, Zhou B, Chia PH, Rizk P, Um M, Udolph G, Yang H, Lim B, Lodish HF. MicroRNA-125b promotes neuronal differentiation in human cells by repressing multiple targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5290–305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01694-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shi Y, Huang F, Tang B, Li J, Wang J, Shen L, Xia K, Jiang H. MicroRNA profiling in the serums of SCA3/MJD patients. Int J Neurosci. 2013 Aug 22; doi: 10.3109/00207454.2013.827679. 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bazan NG, Calandria JM, Gordon WC. Docosahexaenoic acid and its derivative neuroprotectin D1 display neuroprotective properties in the retina, brain and central nervous system. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2013;77:121–131. doi: 10.1159/000351395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Orr SK, Palumbo S, Bosetti F, Mount HT, Kang JX, Greenwood CE, Ma DW, Serhan CN, Bazinet RP. Unesterified docosahexaenoic acid is protective in neuroinflammation. J Neurochem. 2013 Aug 6; doi: 10.1111/jnc.12392. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12392. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hennig R, Kehl T, Noor S, Ding XZ, Rao SM, Bergmann F, Fürstenberger G, Büchler MW, Friess H, Krieg P, Adrian TE. 15-lipoxygenase-1 production is lost in pancreatic cancer and overexpression of the gene inhibits tumor cell growth. Neoplasia. 2007;9:917–926. doi: 10.1593/neo.07565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lukiw WJ, Cui JG, Marcheselli VL, Bodker M, Botkjaer A, Gotlinger K, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. A role for docosahexaenoic cid-derived neuroprotectin D1 in neural cell survival and Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2774–2783. doi: 10.1172/JCI25420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Palacios-Pelaez R, Lukiw WJ, Bazan NG. Omega-3 essential fatty acids modulate initiation and progression of neurodegenerative disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41:367–74. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Uderhardt S, Krönke G. 12/15-lipoxygenase during the regulation of inflammation, immunity, and self-tolerance. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90:1247–56. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mohri T, Nakajima M, Takagi S, Komagata S, Yokoi T. MicroRNA regulates human vitamin D receptor. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1328–1333. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lehmann DJ, Refsum H, Warden DR, Medway C, Wilcock GK, Smith AD. The vitamin D receptor gene is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2011;504:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wang L, Hara K, Van Baaren JM, Price JC, Beecham GW, Gallins PJ, Whitehead PL, Wang G, Lu C, Slifer MA, Züchner S, Martin ER, Mash D, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Gilbert JR. Vitamin D receptor and Alzheimer’s disease: a genetic and functional study. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1844. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Garcion E, Wion-Barbot N, Montero-Menei CN, Berger F, Wion D. New clues about vitamin D functions in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:100–105. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lu’o’ng KV, Nguyen LT. The role of vitamin D in Alzheimer’s disease: possible genetic and cell signaling mechanisms. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:126–36. doi: 10.1177/1533317512473196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].DeLuca GC, Kimball SM, Kolasinski J, Ramagopalan SV, Ebers GC. Review: the role of vitamin D in nervous system health and disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:458–484. doi: 10.1111/nan.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nissou MF, Brocard J, El Atifi M, Guttin A, Andrieux A, Berger F, Issartel JP, Wion D. The transcriptomic response of mixed neuron-glial cell cultures to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 includes genes limiting the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35:553–564. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dursun E, Gezen-Ak D, Yilmazer S. Beta amyloid suppresses the expression of the vitamin d receptor gene and induces the expression of the vitamin d catabolic enzyme gene in hippocampal neurons. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;36:76–86. doi: 10.1159/000350319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pahl L, Schubert S, Skawran B, Sandbothe M, Schmidtke J, Stuhrmann M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D decreases HTRA1 promoter activity in the rhesus monkey - A plausible explanation for the influence of vitamin D on age-related macular degeneration? Exp Eye Res. 2013 Sep 27; doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.09.012. 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Annweiler C, Brugg B, Peyrin JM, Bartha R, Beauchet O. Combination of memantine and vitamin D prevents axon degeneration induced by amyloid-beta and glutamate. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 Sep 4; doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.07.029. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Manson JE, Bassuk SS, Lee IM, Cook NR, Albert MA, Gordon D, Zaharris E, Macfadyen JG, Danielson E, Lin J, Zhang SM, Buring JE. The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL): rationale and design of a large randomized controlled trial of vitamin D and marine omega-3 fatty acid supplements for the primary prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:159–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Holló A, Clemens Z, Lakatos P. Epilepsy and Vitamin D. Int J Neurosci. 2013 Sep 25; doi: 10.3109/00207454.2013.847836. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 24063762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Taghizadeh M, Talaei SA, Djazayeri A, Salami M. Vitamin D supplementation restores suppressed synaptic plasticity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutr Neurosci. 2013 Jul 23; doi: 10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000080. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Boldin MP, Baltimore D. MicroRNAs, new effectors and regulators of NF-κB. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:205–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pogue AI, Li YY, Cui JG, Zhao Y, Kruck TP, Percy ME, Tarr MA, Lukiw WJ. Characterization of an NF-kappaB-regulated, miRNA-146a-mediated down-regulation of complement factor H (CFH) in metal-sulfate-stressed human brain cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2009;103:1591–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Riazanskaia N, Lukiw WJ, Grigorenko A, Korovaitseva G, Dvoryanchikov G, Moliaka Y, Nicolaou M, Farrer L, Bazan NG, Rogaev E. Regulatory region variability in the human presenilin-2 (PSEN2) gene: potential contribution to the gene activity and risk for AD. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:891–898. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].McLachlan DR, Lukiw WJ, Kruck TP. New evidence for an active role of aluminum in Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1989;16:490–497. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100029826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hill JM, Zhao Y, Clement C, Neumann DM, Lukiw WJ. HSV-1 infection of human brain cells induces miRNA-146a and Alzheimer-type inflammatory signaling. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1500–1505. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283329c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bredy TW, Lin Q, Wei W, Baker-Andresen D, Mattick JS. MicroRNA regulation of neural plasticity and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Niemitz E. TREM2 and Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2012;45:11–12. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Heneka MT, O’Banion MK, Terwel D, Kummer MP. Neuroinflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:919–947. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Xu D, Sharma C, Hemler ME. Tetraspanin12 regulates ADAM10-dependent cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. FASEB J. 2009;23:3674–3681. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-133462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Jones BM, Dua P, Alexandrov PN, Hill JM, Lukiw WJ. Regulation of TREM2 expression by an NF-κB-sensitive miRNA-34a. Neuroreport. 2013;24:318–323. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835fb6b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sen R, Baltimore D. Inducibility of kappa immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein Nf-kappa B by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell. 1986;47:921–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Gilmore TD, Herscovitch M. Inhibitors of NF-kB signaling: 785 and counting. Oncogene. 2006;25:6887–6899. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Gilmore TD, Garbati MR. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling as a strategy in disease therapy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;349:245–263. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Nam NH. Naturally occurring NF-kB inhibitors. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:945–951. doi: 10.2174/138955706777934937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chen X, Liang H, Zhang CY, Zen K. miRNA regulates noncoding RNA: a noncanonical function model. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Lukiw WJ, Alexandrov PN, Zhao Y, Hill JM, Bhattacharjee S. Spreading of Alzheimer’s disease inflammatory signaling through soluble micro-RNA. Neuroreport. 2012;23:621–626. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835542b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pogue AI, Percy ME, Cui JG, Li YY, Bhattacharjee S, Hill JM, Kruck TP, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. Up-regulation of NF-kB-sensitive miRNA-125b and miRNA-146a in metal sulfate-stressed human astroglial (HAG) primary cell cultures. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1434–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lecrux C, Hamel E. The neurovascular unit in brain function and disease. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;203:47–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Erickson MA, Banks WA. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction as a cause and consequence of Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1500–1513. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]