Abstract

Time-sampled observations of Head Start preschoolers' (N = 264; 51.5% boys; 76% Mexican American; M = 53.11 and SD = 6.15 months of age) peer play in the classroom were gathered during fall and spring semesters. One year later, kindergarten teachers rated these children's school competence. Latent growth models indicated that, on average, children's peer play was moderately frequent and increased over time during preschool. Children with higher initial levels or with higher slopes of peer play in Head Start had higher levels of kindergarten school competence. Results suggest that Head Start children's engagement with peers may foster development of skills that help their transition into formal schooling. These findings highlight the importance of peer play, and suggest that peer play in Head Start classrooms contributes to children's adaptation to the demands of formal schooling.

Keywords: peers, play, Head Start, school competence, kindergarten transition

Understanding factors that promote young children's school competence is important, given that early academic and behavioral adjustment sets the stage for later academic and social competence (La Paro & Pianta, 2000). This is particularly true for children who come from low-income households and are thought to be at risk for difficulties in adjusting to formal schooling (McWayne, Cheung, Green Wright, & Hahs-Vaughn, 2012). Engagement with peers can be influential in several domains (emotional, cognitive, social) that are important for school competence (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). For example, children who enter kindergarten with social skills that have been honed through many experiences with peers may transition to kindergarten with fewer difficulties than children who are less socially mature and have not had as many experiences with peers (Ladd & Price, 1987). In the present study, we observed children's peer play over one year in Head Start classrooms and examined how individual differences in peer play trajectories (i.e., individuals' within-person change over time) predicted school competence a year later at the end of kindergarten.

Development of Peer Play

Based on observations of children in classrooms and childcare settings, children's play has been conceptualized as evolving from infancy to childhood. For example, nearly a century ago, Parten (1932) classified children's play into categories that varied from nonsocial to social play. Parten noted that as children aged, they spent more time in social relative to nonsocial play. Contemporary research only partially supports the sequence described by Parten (Ladd, 2005; Rubin et al., 2006). Although young children increasingly move from playing alone to playing with peers, the development of play is complex and not necessarily sequential. For instance, social play becomes more frequent across early childhood (Farran & Son-Yarbrough, 2001), but nonsocial play also is normative and not replaced by social play (Rubin & Coplan, 1998; Smith, 1978). Furthermore, there are individual differences in the amount of time young children spend playing with peers (Howes, 1988; Howes & Matheson, 1992). Such individual differences have been hypothesized to be associated with factors such as emotionality or regulation (Fabes, Hanish, Martin, & Eisenberg, 2002), cognitive and linguistic competence (Rubin & Daniels-Beirness, 1983), and childcare experiences (Howes, 1987).

The quality of children's play also varies across children and time. For instance, Cohen and Mendez (2009) examined Head Start children's peer play reported by teachers in the fall and spring, and classified play quality at each time point as “disordered” if it was disruptive or disconnected. Some children's quality stayed the same and other children's quality differed from fall to spring (stable disordered [13% of sample], disordered improving [14%], stable nondisordered [64%], and nondisordered declining [9%]).

Despite the attention that the development of children's play has received, we know little about individual differences in trajectories (individuals' within-person quantitative change) of children's observed peer play. We identified only one study of preschoolers' play trajectories. Fabes et al. (2002) examined preschoolers' and kindergarteners' trajectories of observed nonsocial play (playing alone in the company of peers) over three months. The study suggested that change in nonsocial play was not uniform across children, and that individual differences in change were positively associated with negative emotional intensity. A finer-grained examination of within-person change that captures the consistency and frequency of play with peers is missing from the literature. The assessment of children's latent developmental trajectories offers advantages over previously utilized methods that yielded only aggregate group-level information about change in children's play with peers, and did not correct for measurement error.

Frequency of play with peers may be best measured through observations of play. The use of observational measures offers important advantages. Teachers' reports of children's behavior (often used in play research with Head Start samples) have benefits (e.g., observing the child for long periods of time), but they can be biased by characteristics of the child (e.g., gender, reputation; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD], 2002). Observations by trained research assistants are likely to be more objective than teachers' ratings. Observers also are able to devote their attention to the specific behaviors of interest.

One reason developmental trajectories of children's observed peer play have not been an object of focus is that this requires a fairly large sample size and multiple occasions of measurement. Obtaining such data is a demanding and challenging research endeavor. We addressed this gap by using time-sampled observations that allowed us to identify latent trajectories of Head Start children's engagement with peers during free play across the preschool year. Furthermore, our examination of variability in trajectories of play with peers allowed us to investigate the relation of individual differences to the successful transition to kindergarten.

Transition to Kindergarten and its Potential Association with Peer Play

Children's entrance into kindergarten marks a transition for them and their families. It is children's first experience in a more formal learning environment, one in which academic skills are emphasized to a greater degree than in preschool (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). In kindergarten, children spend more time in larger groups of peers relative to preschool (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). The teacher-child relationship becomes more instrumental and less emotionally responsive than in preschool (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004). Furthermore, social and behavioral expectations are higher during kindergarten than in preschool. Children are expected to show sustained attention, be more autonomous, and have more self-control (Love, Logue, Trudeau, & Thayer, 1992). Due to the numerous shifts that occur at the kindergarten transition, pre-academic, behavioral, and social skills have been emphasized as important aspects of school readiness (Snow, 2006). Children's adjustment to kindergarten is predictive of later academic performance and achievement (Claessens, Duncan, & Engel, 2009).

Relationships with peers, parents, and teachers are key mechanisms through which children gain the skills necessary for school readiness (Mashburn & Pianta, 2006), and multiple theoretical perspectives describe how children may learn through their interactions with peers. For instance, constructivists (Vygotksy, 1978) assert that children can learn with the assistance of more experienced and knowledgeable peers. Peer play provides a context in which children can learn academic skills from more advanced playmates, and is associated with cognitive growth (Wentzel, 2009). Social learning theorists suggest that children can learn from others by observation (Bandura, 1977). Children imitate same-age and older peers (Brody & Stoneman, 1981), and can learn new actions by observing others (Nielsen, Moore, & Mohamedally, 2012). Interactions with peers also provide opportunities for development of a variety of skills that support children's academic and social competence. In peer play, children receive feedback, and have opportunities to practice problem solving, communication, social coordination, and perspective taking (Cheah, Nelson, & Rubin, 2001; Coplan & Arbeau, 2009). Sociodramatic peer play provides children with practice in regulating their behavior in ways that help sustain the interaction (Elias & Berk, 2002; Howes, 1992). Even peer interactions characterized by conflict may benefit children as they learn to negotiate a balance between their own and others' desires (Ladd, 2005). Given the ways in which children can learn from their peers, it is not surprising that children's frequency of engagement with peers has been positively associated with numerous outcomes, including cognitive skill, language development, perspective taking, autonomy, and academic performance (for meta-analysis see Fisher, 1992; Provost & LaFreniere, 1991). Peer play appears to help set the stage for the transition to kindergarten.

Although the developmental benefits of children's early engagement with peers have been described by theorists (Vygotsky, 1967) and have been the subject of studies for decades (Fisher, 1992), research is needed that tracks children's trajectories of peer engagement over time and how these trajectories relate to developmental outcomes. Trajectories of peer play are important to investigate as they may reflect children's accumulation of new experiences, which may result in the development of skills that support the transition to school. In a review of the literature, we found no study in which individuals' trajectories of observed peer play were examined in relation to school competence. Given the research that shows children's adaptation to kindergarten and early schooling is related to later academic performance and achievement, understanding how trajectories of peer play in preschool predict kindergarten competence is important. The present study fills this gap by observing children's peer play over a year of preschool and examining their peer play trajectories in relation to the transition to kindergarten.

Socio-demographic Risk and the Transition to Kindergarten

Identifying how peer play trajectories foster social and academic skills may be especially important for children from families with socio-demographic risk factors associated with poor adjustment to the transition to formal schooling. Latino children from low-income families have been rated as having lower interpersonal skills than White children at entry to kindergarten (Galindo & Fuller, 2010). In addition, children from impoverished backgrounds may have difficulty adjusting to the academic demands, behavioral expectations, length of the school day, and interacting with other children, particularly compared to peers from middle- and high-income households where there likely are more resources and supports for children's interpersonal and cognitive competencies (Hill, 2001; Patterson, Kupersmidt, & Vaden, 1990).

Much of the existing research in which children's play has been examined in relation to school or academic competence has been conducted with White children and/or children from middle-income families. Few studies have investigated play of children from low-income families or racial/ethnic minority children. The existing body of research with Head Start children suggests that preschoolers' positive interactive play in the classroom (prosocial and cooperative interactions) is associated with positive outcomes including vocabulary, literacy, and mathematic skills, as well as positive learning engagement in the classroom (Coolahan, Fantuzzo, Mendez, & McDermott, 2000; for a review see Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2012).

A limitation of this literature is that many studies in which Head Start children's play has been examined in relation to school adjustment have been comprised mostly of African American children. Recently, calls have been made to extend this investigation to low-income samples from other backgrounds, such as Latino or Asian American children (Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2012). It also is important to understand peers' role in language-minority children's school adjustment and competence, particularly given that language-minority students comprise approximately 21% of all students in the U.S. (National Center for Education Statistics, 2010).

Our study helps to address these gaps, as our sample was comprised of children in a Head Start program, many of whom were Mexican American and did not speak English as their primary language. Many children in our study had more than one factor that has been related to increased risk (e.g., cumulative risk) for maladaptive social-emotional, cognitive, and behavioral, outcomes, as well as poor school readiness (McLoyd, 1998; Raver & Knitzer, 2002).

The Present Study

We had two aims for the present study: 1) to describe developmental trajectories of peer play across one academic year of preschool and 2) to determine if peer play trajectories in preschool predict school competence in kindergarten. Some researchers have categorized the content of play (Smilansky, 1968) or utilized measures that incorporate the social context and content of play (Rubin, 2001). Although the content of play is developmentally salient (Rubin et al., 2006), because little is known about the developmental trajectories of peer play during the preschool period, and obtaining information in intensive observations is extremely challenging, we focused only on the identification of trajectories of children's engagement in play with peers.

We used an observational procedure in which Head Start children were observed during free-play over the course of the fall and spring. Approximately a year later, kindergarten teachers reported on these children's school competence. In this study of at-risk children's adjustment to kindergarten, we provide further exploration of how Head Start children's socio-emotional skills contributed to their adjustment to formal schooling. Such findings may highlight strategies that will help at-risk children be successful in early schooling.

We hypothesized that children's peer play would increase over the school year, on average, and that there would be individual differences in peer play trajectories. We expected that children with higher initial levels of peer play would exhibit better kindergarten school competence because they would have more frequent peer play across preschool, all else being equal (including rate of change in peer play). We expected children with higher slopes of peer play would exhibit better kindergarten competence because they would accumulate more peer experiences by the end of preschool, all else being equal (including initial levels of peer play).

Observed positive emotionality during peer play interactions was included as a covariate. We included it as a way to control for differences between children in the affective tone of their peer interactions, and to help us test whether differences in engagement in peer play itself predicted kindergarten school competence independent of the affective nature of play. In addition, receptive vocabulary skills and language in which the vocabulary measure was administered (English or Spanish) were included as covariates, given that vocabulary might be expected to positively relate to peer play and kindergarten school competence.

Gender differences in which girls' teacher-reported play interaction (cooperative and successful peer play) is higher than boys' have been found in Head Start samples (Coolahan et al., 2000). Gender differences in observed play with peers occasionally, but not always (Farran & Son-Yarbrough, 2001; Reuter & Yunik, 1973), have been found. For example, boys have exhibited more observed interactive (associative and cooperative) play than girls (Provost & LaFreniere, 1991), but this difference has varied by classroom type (Johnson & Ershler, 1981). In contrast, girls have exhibited more observed play with peers than boys in other studies (Tizard, Philps, & Plewis, 1976). It is unclear if the inconsistency in gender differences is due to differences in measurement, demographics, or other factors. Thus, we examined gender differences in trajectories of peer play, as well as in the potential relation between trajectories of peer play and kindergarten school competence, in an exploratory fashion.

Method

Participants

Participants were a part of a research project aimed at understanding children's adjustment to school. Participants were drawn from 18 Head Start classrooms from seven schools in a Southwestern metropolitan area of the US. Schools served native Spanish-speaking and English-speaking children. On average, there were 15 students per classroom. Three cohorts were recruited, with each cohort representing one preschool year of data collection. Parental consent was obtained for 292 children (out of 295; 99%). For children with data collected during two preschool years (n = 16), we omitted the child's first year of data collection. Children who were missing data in either the fall (n = 4) or spring (n = 20) due to late enrollment or disenrollment were excluded. As a group, these late-enrolled or disenrolled children were significantly younger than children who were enrolled across the entire year (Ms = 48.82 and 52.49 months, SDs = 6.32 and 4.84, respectively, p < .05), but did not differ significantly on other demographic variables. We omitted four additional children who were enrolled in the fall and spring but had low numbers of observations (< 40) due to absences. These data were excluded because of past research highlighting that data from children with large numbers of missing data due to low attendance or disenrollment are unreliable (Martin & Fabes, 2001).

Our final sample included 264 children (136 boys). At the beginning of the fall, children were between 37 and 72 months old (M = 53.11, SD = 6.15; 74% were 48 to 58 months olds). According to parents' reports, the majority of children were Mexican American (74%). The remaining distribution included 7% European American; 7% African American; and 7% were Asian American, Native American, and other races/ethnicities (5% were not sure). Many children came from homes in which parents reported that Spanish was the primary language spoken (60%). Reporting parents were married and never divorced (41.3%), divorced and single (4.9%), divorced but living with a partner (1.9%), separated (4.5%), widowed (.4%), never married and single (13.6%), together but never married (22%), or other (1.5%; 9.8% missing). Parent-reported annual family income ranged from under $10,000 to $70,000–80,000. The majority (82.1%) of parents who reported their income indicated that the family made $20,000–30,000 or less (median and mode = $10,000–20,000).

In the late spring of the year following Head Start, each child's kindergarten teacher was contacted for school competence data. Teachers and families were paid for participation ($25 per child and $40, respectively), and children received a small toy. One hundred and eighty-one children from the sample (69%) participated in the kindergarten follow-up assessment. The attrition principally was because we were unable to locate the children (e.g., due to moving).

Demographic variables were analyzed for attrition status (having preschool and kindergarten data vs. having preschool but not kindergarten data) differences using t-tests and Pearson chi-square tests. There were no differences for child's gender, annual family income, or parents' education. Children with kindergarten data were older at the beginning of preschool than children without kindergarten data (Ms = 54.14 and 50.82 months, SDs = 5.26 and 7.30, respectively), t(120.55) = −3.712, p < .001, 95% CI [−5.10, −1.55], Cohen's d = .56. Children who spoke Spanish were more likely than English speakers to have kindergarten data, χ2(1) = 6.30, p = .01 (Φ = .16, p = .01). In addition, European American children and children of other races (African American, Asian American, Native American, and others combined [to prevent sparse data]) were less likely than Hispanic children to have kindergarten data, χ2(2) = 18.65, p < .001 (Φ = .27, p < .001). Variables found to differ by attrition were included as auxiliary variables in supplementary models to improve the likelihood that data met the missing at random (MAR) assumption. Model fit, direction of relations, and significance of estimates did not differ when auxiliary variables were included. Models reported here did not include auxiliary variables.

Demographic variables were analyzed for cohort differences using ANOVAs and Pearson chi-square tests. There were no cohort differences for child's age, gender, language, race, or family income. However, parents' education differed by cohort, χ2(4) = 11.47, p = .02 (Cramer's V = .17, p = .02). Specifically, 56.9%, 34.5%, and 63.1% of parents within cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively, had a high school education or less; 32.3%, 47.3%, and 26.2% of parents within cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively, had some vocational school or college; and 10.8%, 18.2%, and 10.7% of parents within cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively, completed at least a college degree.

Procedures and Measures

Time-sampled observations of play behaviors were gathered throughout the fall and spring semesters of preschool. Bilingual coders (36 females, 8 males) were trained for at least one month by three graduate research assistants who had considerable experience in the observational methodology (language observed in children's interactions with teachers or peers was 71% English, 26% Spanish, and 3% both English and Spanish). Coders practiced until they reached at least 80% reliability with their trainers. Reliability was assessed weekly. Coders were in children's classrooms 5.68 days per month (SD = 2.7, range = 2 to 16) on average and were unaware of study hypotheses.

Coders used a randomly ordered list of participating children in a classroom. They observed each child for 10-seconds, recorded the nature of the child's play, and observed the next child on the list. Once observers reached the bottom of the list, they waited five minutes to record any notes and provide more time for children to re-sort themselves in terms of their interactions and activities. Then observers repeated their observation from the top of the list. In general, it took about an hour to complete one round of observations, and coders were encouraged to complete each round. Multiple observations were gathered indoors and outdoors for each child on each observation day during a 2- to 3-hour shift. Each coder averaged 367.30 observations per month (SD = 260.72, range = 69 to 1339).

This method successfully has been used to document preschoolers' activities and play partners (Martin & Fabes, 2001). Only observations that occurred during indoor or outdoor free-play (children freely decide what to do, with whom, and where to do it) were included in analyses. A total of 65,173 free play observations were collected (median = 245.50 per child, M = 239.97, SD = 75.41). The range in observations per child (42 – 406) was due to children's attendance and availability. Over 95% of the children had more than 100 observations. Children were observed an average of 5.52 times per day (SD = 1.79).

Peer play

Observers coded children's activity during the 10-sec observations. Observations classified as peer play were those in which a child was involved in verbal or physical activity with at least one other child (including interactions that were positive and affiliative or conflicted and agonistic) or was in very close proximity and engaged in the same task as another child (Bakeman & Brownlee, 1980; Robinson, Anderson, Porter, Hart, & Wouden-Miller, 2003). Observations in which children were playing alone, were doing nothing, or were engaged only with teachers were not coded as peer play. For 15% of the observations, two observers coded the same child's behavior. Based on 6,481 simultaneous reliability observations, the average kappa was .92.

Data collection took place beginning in September and ending in May. We calculated each child's proportion of peer play during each month by taking the number of peer play observations and dividing it by the total number of observations for that child during that month. Some months had fewer observations per child due to holiday vacation or because observational coders were being trained. For this reason, we combined data from months 4 and 5. Thus, data were aggregated into eight time points across the preschool year. Children were required to have at least three (they typically had more) observations within a time point to receive a proportion score. This resulted in nine children not receiving a score during one time point.

Positive emotionality in peer play

For each play observation, observers rated the degree of children's positive emotion during the 10-sec period. Intensity and duration was taken into account (0 = no evidence of positive emotion, 1 = minimal evidence of positive emotions [e.g., slight smile, saying “this is fun” in a soft, unexcited voice], 2 = moderate evidence [e.g., enduring smile or laughter, saying “this is fun” in excited voice] lasting at least 2 to 3 secs, 3 = strong evidence [e.g., loud laughter, screaming in joy or excitement] lasting at least 2 to 3 secs).

Based on 6,481 simultaneous observations (15% of observations), the intraclass correlation was .78. Children's ratings were averaged during each month. An average of the monthly positive emotionality scores was used as a positive emotionality composite.

Vocabulary

Early in the fall of preschool, each child was individually administered either the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (PPVT-III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997) in English (n = 126), or the Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody (TVIP; Dunn, Padilla, Lugo, & Dunn, 1986) in Spanish (n = 127). The PPVT-III and the TVIP are standardized measures of receptive vocabulary that are reliable and valid (Dunn & Dunn, 1997; Dunn et al., 1986). The language chosen for administration (Spanish or English) was based on teachers' recommendations of each child's language preference. The TVIP was developed using the most appropriate items from the PPVT-III for a Spanish population. The PPVT-III and TVIP have the same number of total questions and most questions are identical, although some items differ between versions. Individuals were administered the tests by trained bilingual RAs. RAs presented each child with four pictures and asked the child to point to the picture that best represented the word spoken by the RA. Items were administered until the child incorrectly answered eight items in a set of 12. Deviation-type normative scores were calculated based on items answered correctly and the child's performance relative to other children that were his or her age (i.e., national norms). For growth models, scores were divided by 100 to reduce ill-scaled variances and aid convergence.

Kindergarten school competence

Toward the end of the spring semester of kindergarten, each child's teacher completed questionnaires (in English). Teachers were asked to assess each child on a variety of characteristics, several of which assessed the overall quality of the child's kindergarten school competence. Composite scores from these measures were used as indicators of a latent variable representing kindergarten school competence.

Penn Interactive Peer Play Scales

To assess perceptions of children's peer interactive skills, kindergarten teachers completed the 32-item modified version of the Penn Interactive Peer Play Scales (PIPPS; Fantuzzo, Coolahan, Mendez, McDermott, & Sutton-Smith, 1998). The PIPPS has been widely used in Head Start samples and the modified version has shown good reliability and validity (Coolahan et al., 2000; Fantuzzo et al., 1998). Teachers indicated how frequently they observed behaviors in a child on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = often, 4 = always), and subscale items were averaged: 1) play interaction (children's play strengths; e.g., “comforts others when hurt or sad”; α = .83 [all alphas computed on this sample]), 2) play disruption (behaviors that interfere with peer play; e.g., “verbally assaults others”; α = .92), and 3) play disconnection (nonparticipation in peer play; e.g., “needs help to start playing”; α = .92). Subscale scores (interaction, disruption [reversed], and disconnection [reversed]) were correlated, rs(179) = .50 to .69, ps < .001. A composite that reflected positive peer interaction skills was computed by averaging the subscale scores. For latent growth models, the composite scores were divided by 10 to aid convergence.

Teacher Rating Scale of School Adjustment

Kindergarten teachers completed the Teacher Rating Scale of School Adjustment (TRSSA; Birch & Ladd, 1997), which assesses children's 1) cooperative participation (7 items; e.g., “follows teacher's directions”; α = .93), 2) self-directedness (4 items; e.g., “seeks challenges”; α = .76), 3) school liking (5 items; e.g., “enjoys most classroom activities”; α = .86), and 4) school avoidance (5 items; e.g., “feigns illness at school”; α = .69). Teachers rated the degree to which items described a child using a 3-point rating scale (0 = no, 1 = sometimes, 2 = yes), and items were averaged within subscale. Cooperative participation and self-directedness subscales were averaged to form a school participation composite, r(179) = .66, p < .001. School liking and school avoidance (reversed) were averaged to form a school-liking composite, r(177) = .44, p < .001. For latent growth models, both composite scores were divided by 10 to aid convergence.

Developmental Profile

Kindergarten teachers completed the Developmental Profile (Fabes, Martin, Hanish, Anders, & Madden-Derdich, 2003; Meisels, 1996), which is a multidimensional school readiness and adjustment profile. Teachers assessed children's personal, social, and academic qualities associated with school adjustment using five subscales. The subscales included: 1) social development (6 items; e.g., “responds appropriately to others' emotions and intentions”; α = .93), 2) school-specific instrumental development (8 items; “generally completes tasks in allotted time”; α = .93), 3) reading and writing (9 items; “uses context clues to predict meaning”; α = .92), 4) logical thinking and use of numbers (10 items; “can count reliably up to 12”; α = .92), and 5), and perceptual-motor development (5 items; “enjoys and feels confident during physical activities”; α = .89). Teachers rated each item using a 4-point scale that reflected the stage of development (1 = not yet developed, 2 = early stage, 3 = intermediate stage, 4 = proficient), and items were averaged within subscale. The five subscales were averaged into a school adjustment composite, rs (177, 179) = .61 to .84, p < .001. For latent growth models, the composite scores were divided by 10 to aid convergence.

Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Gender differences in variable means were examined using independent samples t-tests, and significant results are presented in Table 1. Of the peer play interactions, 50% involved dyadic peer play, 33% involved a verbal exchange, 11% involved large motor physical play, 21% were positive, and 4% were disruptive/conflicted (categories were not mutually exclusive). Zero-order correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | N | M number observations per child | Observed Range | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion peer play Tl | 193 | 17.33 | 0.00–1.00 | .44 | .19 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| Proportion peer play T2a | 258 | 34.79 | 0.00–1.00 | .45 | .13 | 0.35 | 1.15 |

| Proportion peer play T3 | 264 | 39.83 | 0.17–0.79 | .45 | .11 | 0.18 | −0.12 |

| Proportion peer play T4/T5 | 248 | 15.40 | 0.00–1.00 | .47 | .19 | −0.22 | −.002 |

| Proportion peer play T6 | 205 | 37.85 | 0.05–0.73 | .49 | .13 | −0.64 | 0.24 |

| Proportion peer play T7b | 257 | 39.37 | 0.17–0.88 | .50 | .12 | −0.26 | −0.06 |

| Proportion peer play T8 | 253 | 51.19 | 0.24–0.78 | .52 | .11 | −0.08 | −0.21 |

| Proportion peer play T9 | 202 | 27.67 | 0.13–1.00 | .54 | .17 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| Preschool positive emotionality | 264 | 238.97 | 1.01–2.36 | 1.46 | .26 | 0.59 | −0.26 |

| Vocabularyc | 252 | n/a | 45.00–123.00 | 84.81 | 14.11 | 0.03 | −0.37 |

| Peer interactionc,d | 181 | n/a | 0.35–2.70 | 1.98 | .44 | −0.94 | 0.86 |

| School participationc,e | 181 | n/a | 1.00–3.00 | 2.45 | .49 | −0.92 | 0.20 |

| School likingc,f | 179 | n/a | 0.41–2.21 | 2.01 | .30 | −2.18 | 5.88 |

| School adjustmentc,g | 181 | n/a | 1.46–4.00 | 3.30 | .59 | −0.87 | 0.12 |

T = time.

Gender difference: t(253.45) = −2.03, p = .04, CI 95% [−.06, −.001], boys' M = .47, girls' M = .44, Cohen's d = .23.

Gender difference: t(252.11) = 2.30, p = .02, CI 95% [.005, .06], boys' M = .48, girls' M = .51, Cohen's d = .25.

Statistics computed prior to being rescaled for use in latent growth model.

Gender difference: t(169.19) = 3.29, p = .001, CI 95% [.08, .33], boys' M = 1.88, girls' M = 2.09, Cohen's d = .49.

Gender difference: t(174.64) = 3.45, p = .001, CI 95% [.10, .38], boys' M = 2.34, girls' M = 2.58, Cohen's d = .51.

Gender difference: t(176.18) = 2.08, p = .04, CI 95% [.005, .18], boys' M = 1.97, girls' M = 2.06, Cohen's d = .31.

Gender difference: t(174.05) = 3.51, p = .001, CI 95% [.13, .46], boys' M = 3.16, girls' M = 3.45, Cohen's d = .51.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peer 1 | .33*** | .36*** | .19* | .25** | .21** | .15* | −.01 | .23*** | .04 | .11 | .05 | .19* | .05 |

| 2 Peer 2 | - | .41*** | .25*** | .27*** | .15* | .06 | −.02 | .18** | .02 | .10 | .02 | .12 | .02 |

| 3 Peer 3 | - | .46*** | .37*** | .34*** | .27*** | .15* | .09 | −.01 | .14 | .12 | .18* | .03 | |

| 4 Peer 4/5 | - | .36*** | .23*** | .16* | .18* | .11 | .06 | .18* | .17* | .17* | .16* | ||

| 5 Peer 6 | - | .58*** | .42*** | .31*** | .14* | −.01 | .07 | .08 | .06 | −.08 | |||

| 6 Peer 7 | - | .43*** | .36*** | .17** | .02 | .19* | .14 | .12 | .08 | ||||

| 7 Peer 8 | - | .32*** | .15* | .01 | .14 | .13 | .21** | .12 | |||||

| 8 Peer 9 | - | .12 | −.03 | .23** | .21** | .17* | .21* | ||||||

| 9Pos | - | .09 | .05 | .07 | .09 | .13 | |||||||

| lOVocab | - | −.06 | −.04 | −.04 | .10 | ||||||||

| 11 Interact | - | .76*** | .59*** | .71*** | |||||||||

| 12Partic | - | .54*** | .78*** | ||||||||||

| 13 Liking | - | .53*** | |||||||||||

| 14 Adjust | - |

Notes. Degrees of freedom range = 123 to 262. Peer = Proportion peer play. Pos = Observed preschool positive emotionality. Vocab = Vocabulary. Interact = Peer interaction. Partic = School participation. Liking = School liking. Adjust = School adjustment.

p < .50.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Study variables measured during preschool were examined for differences by attrition status using t-tests. No significant differences (of 10 possible) were found. Study variables measured during preschool and kindergarten were examined for differences by cohort using ANOVAs. Three differences (of 14 possible) were found by cohort. The proportion of peer play during month 6 differed across cohort, F(2, 202) = 13.22, p < .001 (η2 = .12). According to Tukey's HSD comparisons, all pairs of means [Ms = .47, .36, and .53 for cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively] differed (ps < .01). The proportion of peer play during month 9 differed across cohort, F(2, 199) = 13.04, p < .001 (η2 = .12). According to Tukey's HSD comparisons, cohort 3's mean differed (ps < .001) from the other cohorts' [Ms = .52, .49, and .62 for cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively]. The positive emotionality composite differed across cohort, F(2, 260) = 20.64, p < .001 (η2 = .14). According to Tukey's HSD comparisons, all pairs of means [Ms = 1.58, 1.45, and 1.36 for cohort 1, 2, and 3, respectively] differed (ps < .05).

Analytic Plan to Address Study Aims

Our first aim was to describe the trajectories of peer play across one year of preschool. We examined peer play in a latent growth model in which the means and variances for the intercept and linear slope factors were estimated. The intercept represented the expected value during month 1 of Head Start, and the slope represented the rate of change per month of Head Start. Residual variances were allowed to vary across time points.

Our second aim was to examine prediction of kindergarten school competence from peer play trajectories during preschool. A latent construct reflecting kindergarten competence was indicated by peer interaction, school participation, school liking, and school adjustment composites. Kindergarten competence was regressed on the intercept and slope of the peer play growth model. The intercept and slope of peer play, as well as kindergarten competence were regressed on four covariates: children's gender (occasional gender differences were found for peer play, and girls often were rated higher than boys in kindergarten competence, see Table 1), mean-centered vocabulary (PPVT) score (not significantly related to peer play or kindergarten competence variables; see Table 2), language in which the PPVT was administered (Spanish speakers had higher scores on the peer interaction and school participation composites, rs [175] = .18 and .22, ps = .02 and .003, respectively), and children's mean-centered preschool positive emotionality (positively related to peer play but not kindergarten competence; see Table 2).

Based on the MAR assumption, models were estimated using a full information maximum likelihood estimator (maximum likelihood robust; MLR) in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Head Start children's data were nested within 18 classrooms, but we did not use multilevel modeling because group-level variances and standard errors may be underestimated when the number of groups is small (Maas & Hox, 2005). However, we used the type = complex function in Mplus to take dependency in data into account when computing standard errors and the chi-square when the number of estimated parameters did not exceed the number of classrooms (i.e., the latent growth model for preschool peer play).

Global fit of the models was evaluated using the chi-square test, SRMR, RMSEA, and CFI. Although “rules of thumb” regarding model fit evaluation have not been established for latent growth models which incorporate both the covariance and mean structure (Wu, West, & Taylor, 2009), we took SRMR, RMSEA, and CFI values close to .08, .05, and .95 respectively, as indicative of good fit between the model and data. These indices were used in conjunction as they may be differentially sensitive to misspecification in the mean structure (Wu et al., 2009). Note that null models appropriate for latent growth models were estimated and utilized in hand-calculation of the CFIs reported in this manuscript (Widaman & Thompson, 2003).

Latent Growth Model of Preschool Peer Play

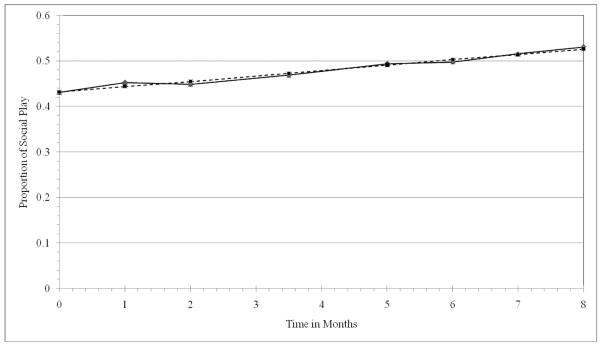

The model was respecified one time after initial estimation to improve local fit (global fit was good) by estimating a covariance between the residuals of peer play at month 3 and 4/5, and at month 6 and 7, as suggested by modification indices. The resulting model was a good fit, χ2(N = 263; df = 29) = 18.75, p = .93, scaling correction factor for MLR = 1.43, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .06, and CFI = 1.00. Standardized residuals for the mean vector and the covariance matrix were small. No modification index exceeded 3.84. The means and variances for the intercept and linear slope from the unstandardized solution were: InterceptPeerPlay (M = .432, p < .001; s2 = .009, p < .001), and SlopePeerPlay (M = .012, p < .001; s2 = .000, p < .001). Unstandardized estimates were numerically small (e.g., the slope variance was in the ten-thousandths) because the potential range of our observed indicators was zero to one, but often were statistically significant. Peer play was moderately frequent at the beginning of the school year and increased over time on average, but there were individual differences in level and change of peer play. The intercept and slope covariance was negative (unstandardized estimate = −.001 p < .001, completely standardized estimate = −.696, p < .001). Children with higher initial peer play had lower (less positive) rates of change than children with lower initial peer play (Figure 1 presents the observed-sample and model-estimated means). R2 values indicated that the growth trajectory accounted for significant variability (range 14% – 52%) in observed peer play at each time point.

Figure 1.

Observed-sample means and model-estimated means of proportion of peer play over time. The dashed line indicates sample means. The solid line indicates model-estimated means.

Prediction of Kindergarten School Competence from Trajectories of Head Start Peer Play

A confirmatory factor model was specified for kindergarten competence. It was a good fit, χ2(N = 181, df = 2) = 3.78, p = .15, scaling correction factor for MLR = 1.41, RMSEA = .07, CFI = .96, and SRMR = .02. Loadings were significant and in the expected direction.

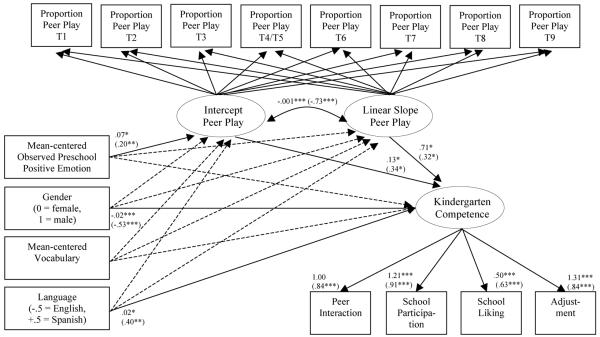

Kindergarten competence was regressed on the Head Start peer play intercept and slope. The model (see Figure 2) was a good fit according to most indices, but the chi-square was significant, χ2(N = 252, df = 97) = 127.08, p = .02, scaling correction factor for MLR = 1.00, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .06, and CFI = .96. Some modification indices exceeded 3.84 but did not make sense to incorporate.

Figure 2.

Latent growth model analysis for peer play predicting kindergarten competence. Loadings for the intercept factor were set at 1.0 for all indicators. Loadings for the linear slope factor were set at 0, 1, 2, 3.5, 5, 6, 7, and 8 for T1, T2, T3, T4/T5, T6, T7, T8, and T9 indicators, respectively. For clarity, non-significant path estimates are not reported. Significant unstandardized estimates and associated significance levels are presented. Significant standardized estimates and associated significance levels are presented in parentheses (completely standardized estimates for continuous predictors and standardized only on Y estimates for categorical predictors). Covariates freely correlate. The correlations between the residuals for T3 and T4/5, and for T6 and T7 peer play were positive and statistically significant, p < .001 (not included in the figure for clarity). *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Observed positive emotionality during peer play predicted the intercept (unstandardized b = .07, p = .01), but not slope (unstandardized b = −.001, p = .79), of peer play. Gender (0 = female, 1 = male; unstandardized b = .003, p = .85, and b = −.003, p = .25), vocabulary (unstandardized b = .01, p = .84, and b = −.001, p = .94), and language of vocabulary test administration (unstandardized b = .01, p = .56, and b = .000, p = .94) did not significantly predict the intercept or slope of peer play, respectively. R2 values indicated that a non-significant amount of variance in the intercept and slope of peer play was accounted for by covariates, 4.2% and 1.1%, respectively.

Children's gender (unstandardized b = −.02, p < .001) and language of vocabulary test administration (unstandardized b = .02, p = .01) were related to kindergarten competence. Observed positive emotionality (unstandardized b = .01, p = .54) and vocabulary (unstandardized b = .01, p = .67) were not related to kindergarten competence. Girls and children who were given the vocabulary measure in Spanish were rated as having higher kindergarten competence. Consistent with our hypothesis, the intercept and slope of preschool peer play predicted kindergarten competence (unstandardized b = .13, p = .03, and b = .71, p = .02, respectively). Head Start children with more frequent initial peer play had better teacher-rated kindergarten competence a year later. Specifically, the coefficient for the peer play intercept may be conceptualized to represent the average difference in kindergarten competence (i.e., .13) for children who differ by one-unit in the intercept, but have the same values for their slope (i.e., children who have parallel growth but different starting points) and the same values for the covariates. In addition, Head Start children with higher rates of change in peer play had better teacher-rated kindergarten competence a year later. Specifically, the coefficient for the peer play slope may be conceptualized to represent the average difference in kindergarten competence (i.e., .71) for children who differ by one-unit in the slope, but have the same values for their intercept (i.e., growth rates differ but same starting point) and the same values for covariates. The R2 indicated that a significant amount, 19%, of the variance in kindergarten competence was accounted for by the intercept and the slope of peer play as well as the covariates.

Because the PIPPS measure and social development subscale of the Developmental Profile assessed aspects of social behavior, we re-ran the analyses that assessed prediction of kindergarten school competence from peer play with these indicators excluded from the model. Estimates of interest for models including or excluding these components of school competence were similar, with one exception. Prediction of school competence from the intercept of peer play became marginally significant (i.e., p = .058) when the social aspects of school competence were excluded. Prediction of school competence from the slope of peer play remained significant even when the social aspects of kindergarten competence were removed from the model.

Exploration of Gender Differences

We ran several series of models to examine gender differences (see online supplementary materials). The first series indicated invariance of loadings, but not intercepts, for indicators of kindergarten school competence for boys and girls. Thus, a unit-difference in the latent kindergarten school competence factor was associated with an equivalent difference in the observed indicators for boys and girls. However, a given score on the latent kindergarten school competence factor was not necessarily associated with the same score on the indicators for boys and girls. Thus, latent factor means for school competence were not compared for boys and girls.

The second series indicated invariance of the latent intercept mean, latent slope mean, latent intercept variance, latent slope variance, and intercept/slope covariance of the peer play growth model for boys and girls. The final series indicated that the prediction of kindergarten competence from the intercept and slope of peer play, as well as prediction of outcomes from the covariates (positive emotionality, language, and vocabulary) was not moderated by gender.

Discussion

The surge of interest in school readiness and early school competence from researchers and policy makers highlights the importance and long-term significance of these issues. This emphasis reflects the awareness that what happens to children before they enter formal schooling affects their adjustment to and performance in school. Understanding factors that predict children's kindergarten adjustment is essential because, as noted previously, early adjustment sets the tone for later school competence (La Paro & Pianta, 2000). Identifying these factors is of particular importance for groups of children who are known to be at risk for school adjustment difficulties. In the present longitudinal study, individual differences were found in Head Start children's trajectories of peer play during an academic year. This study adds to the literature by providing a new perspective related to how trajectories of peer play during preschool predict later kindergarten competence, even after controlling for the positivity of these interactions.

Developmental Trajectories of Head Start Children's Peer Play

Our hypotheses regarding the development of peer play during preschool were supported. During the first month of Head Start, the average proportion of children's peer play was. 43. Thus, children in Head Start started off the school year engaging in moderately frequent peer play; on average, 43% of the total time a child was observed, he or she was engaged in peer play. Furthermore, on average, the proportion of peer play increased by .01 each month. By the ninth month, Head Start children were engaged in peer play on average about 53% of the time they were observed. The increase over time in peer play was consistent with previous studies that have shown an increase in the average quantity of peer interactions as young children age (Coplan & Arbeau, 2009; Smith, 1978). Others have suggested that as children's social, linguistic, and cognitive skills develop, they are able to engage in longer and more complex peer interactions (Howes, 1988). In addition to children's growing capability for social exchanges, it is possible that social aspects of play become increasingly entertaining, exciting, and reinforcing for most children as they learn to navigate the social context of Head Start.

The mean-level trajectory for Head Start children's peer play was only part of the story. There was significant variability in the intercept and slope of peer play. Children's proportion of peer play during the first month of Head Start varied. In addition, many children's peer play increased, but some Head Start children stayed the same or even decreased across the year (see online supplementary materials). For example, according to descriptive statistics of the factor scores, the slope of peer play ranged from −.02 to .04 (SD = .01). This variation in the trajectory of peer play was relevant in the prediction of later kindergarten competence. In addition, the intercept and slope of peer play negatively covaried, and indicated that children who interacted with their peers more frequently at the start of preschool relative to their peers had less growth over time. Based on a scatterplot of children's factor scores for the intercept and slope factors (see online supplementary materials), it seems that some children with very frequent initial peer play declined in their peer play over time, but perhaps more often it was the case that children with a low initial frequency of peer play increased in their peer play over time.

Observed positive emotionality during peer play related to peer play trajectories. Children with higher positive emotionality during observed peer play tended to have peer-play trajectories that started higher during the first month of Head Start, but positive emotionality was not predictive of rate of change in peer play across the year in Head Start. It appears that positive emotionality sets the initial stage for preschoolers' rates of social interactions with their classmates. Research has found that children who exhibit positive affect are better liked by peers (Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, & Holt, 1990) and may be attracting more playmates upon entry to preschool. However, factors other than positive emotionality appear to account for changes in these rates over time, and as is discussed below, should be investigated in the future.

In summary, our results were consistent with our hypotheses and the existing literature. Our findings extended the literature by providing information regarding the form, rate, and individual differences in intraindividual change in peer play across the first year of Head Start.

Prediction of Kindergarten School Competence from Head Start Peer Play Trajectories

A critically important aspect of our study was examining whether peer play trajectories in Head Start predicted school competencies a year later after these children entered kindergarten. As hypothesized, we found that Head Start children with high initial levels or higher slopes of peer play tended to exhibit better teacher-rated kindergarten competence. Peer play has been related to academic performance and other factors associated with school adjustment (cognitive and social skills, self-regulation; Elias & Berk, 2002; Fisher, 1992; Howes & Matheson, 1992).

Our findings were consistent with these results, but also augmented the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first study in which rates of change in peer play during Head Start have been found to be predictive of later kindergarten competence. The covariates and play trajectories accounted for 19% of the variation in kindergarten school competence. It is notable that children's proportions of peer play during the first month of preschool were predictive of teacher-rated kindergarten school competence. Kindergarten school competence was rated toward the end of kindergarten. Thus, our school competence measure reflects teachers' perceptions of how children adjusted and performed during the school year and not just immediate adjustment and readiness for kindergarten. Furthermore, relations held after controlling for covariates (positive emotionality in peer play, gender, vocabulary, and language).

Kindergarten school competence was a broad measure that captured multiple facets of competence and school adjustment, such as school liking, ability to follow directions, autonomy, responsibility, cooperative and competent interactions, self-regulation, and academic competence. Head Start children with initially high or increasing trajectories of peer play likely benefit from interactions with their peers in numerous ways that are relevant for later school competence. They have opportunities to practice conducting themselves in a way that promotes harmonious interactions. This probably includes learning to be regulated and cooperative, and developing communication and turn-taking abilities. Having frequent peer interactions is expected to facilitate cognitive and linguistic growth. Moreover, peer play and peer relationships may promote school liking, which may increase children's commitment and engagement during kindergarten. In contrast, preschoolers with initially low or decreasing peer play might miss out on interactions expected to facilitate acquisition of competence-relevant skills. These children may be ill-equipped for the social and academic demands of the kindergarten classroom. Furthermore, a child displaying progressively less frequent peer play might be viewed as atypical and rejected or neglected by their peers, or their rejection or neglect may lead to the necessity of engaging in solitary play. This unwelcoming social environment may create a dislike for school, a negative social reputation, and/or a distrust of others that carries over to kindergarten.

These relations held even when controlling for positive emotionality, which helps confirm that the social nature of peer play contributed to later kindergarten adjustment above and beyond individual differences in the affective experiences children had in these peer interactions. As such, there is something about the social nature of the peer interactions themselves that contributes to enhanced kindergarten competence in a sample of children known to be at risk for problems associated with school adjustment and performance.

Kindergarten competence also was predicted by language in which the child was tested during Head Start. In most studies, language-minority status has been linked to diminished academic adjustment and performance (Kieffer, 2008; McWayne et al., 2012). In our study, we found that children who were tested in Spanish during Head Start had higher kindergarten competence than those tested in English. One possibility for the discrepancy across studies is the breadth of our kindergarten competence measure which, as already described, encompassed socio-emotional competence in the classroom, as well as academic performance. Although speculative, it is possible that Spanish-speaking children were more likely to be taught to cooperate, show respect, and care for others, as these are characteristics emphasized in Latino socialization (Galindo & Fuller, 2010), and these characteristics facilitated the transition to kindergarten. Furthermore, it is possible that the language composition of the peer group played a role, given that the Spanish-speaking children had many other Spanish-speaking peers. Language-minority students were 50–60% of the present sample (depending on how it was defined). It appears that the overall language context needs to be considered when attempting to explicate how language status relates to later school competence and performance. Finally, Spanish-speakers in our sample were not necessarily poor English-speakers; in other words, English proficiency was not controlled. If our finding is replicated, it may have implications for policies and practices related to early intervention for language-minority children, particularly those from low-income backgrounds.

Lack of Gender Differences

We explored gender differences in trajectories of peer play, as well as in the relation between peer play trajectories and kindergarten school competence. Gender differences in the frequency of observed peer play occasionally have been found in which boys produce more peer play than girls (Provost & LaFreniere, 1991), but gender differences have not always been found (Farran & Son-Yarbrough, 2001; Reuter & Yunik, 1973) or have been found in the other direction (Tizard et al., 1976). In the present study, no gender differences were found in the average level or variability of peer play during the first month of preschool, or in the average level or variability of rate of change in observed peer play. These results suggest that trajectories of peer play are similar for Head Start boys and girls. In addition, the relations of peer play trajectories to kindergarten competence did not significantly differ for boys and girls. It is possible that gender differences exist with regard to play quality. Our observations of peer play were focused on the quantity, as opposed to the quality, of peer play; thus, our findings cannot speak to potential gender differences related to the quality of peer play.

Limitations

This study was not without limitations. For example, we did not have data regarding whether all children had been enrolled in preschool prior to enrollment in the study. Thus, we were unable to control for years previously spent in preschool. Also, we relied solely on teachers' reports for kindergarten school competence, and these ratings may be subject to bias (NICHD, 2002). Furthermore, our study was focused on play with peers; thus, other potential environmental influences -most notably, parenting-- were not included in our analysis. Aspects of parenting have been found to relate to children's academic and social functioning when transitioning to school (Barth & Parke, 1993). For example, Head Start preschoolers from Latino families exhibited better school readiness when parents' literacy involvement was higher (Farver, Xu, Eppe, & Lonigan, 2006). Finally, this study had a correlational design and, thus, causality cannot be inferred.

Future Directions and Conclusions

In a meta-analysis investigating the benefits of pretend play, Lillard and colleagues (2013) called for longitudinal efforts to help clarify the nature of relations between play and children's development. In keeping with that suggestion, our study included a large number of naturalistic observations of play during preschool and teachers' reports on a number of measures of kindergarten competence, a relatively large sample size, and longitudinal analyses. The finding that individual differences in trajectories of Head Start children's peer play meaningfully predicted kindergarten school competence is important and highlights the crucial role that peers play in influencing early school adjustment. A logical next step is to identify factors that account for variability in Head Start children's peer play trajectories. As discussed previously, researchers have suggested numerous personal and environment factors that may be related to individual differences in play. However, we know of no study in which factors related to rates of change in preschoolers' play with peers have been examined (Fabes et al., 2002 examined factors related to nonsocial play trajectories). A variety of factors might be expected to prompt a decrease in peer play, such as rejection by peers, the presence of anxiety, or perhaps trouble at home. Increases in peer play likely occur in tandem with the development of capacities that facilitate engagement in peer play (e.g., the ability to take turns), and may be influenced by characteristics that are attractive to peers (e.g., low aggression).

Gaining a deeper understanding of why the development of peer play relates to school competence also is of interest. For example, detailed observations of children's social processes could be used to determine if particular skills are being fostered during play. Understanding more fully what children are doing in these social interactions (e.g., activities, discourse) is an important next step. Furthermore, understanding how to maximize the benefits of peer play seems important. For instance, teachers may create opportunities for peer play and help facilitate learning during peers' interactions through naturally occurring teaching opportunities (Stanton-Chapman & Hadden, 2011). Getting answers to these questions involves intensive repeated measures, often using demanding observational procedures. The data used in this study are a first step towards understanding these processes, and underscore the important role that interactions with peers at preschool have for children's later school adjustment. That early school performance is predictive of later school adjustment and competence (Duncan et al., 2007), highlights the importance of our research and calls for more efforts like these.

Our sample was comprised of children in Head Start preschools, many of whom were Mexican-American and Spanish-speaking. As such, the present study adds to the literature by examining trajectories of peer play in classrooms comprised of a large number of children from Spanish-speaking households. Our findings revealed that trajectories of peer play predicted kindergarten competence for these children in Spanish-predominant classes. Understanding peers' role in language-minority children's school adjustment and competence is a significant goal, and is important because during day-to-day classroom routines preschoolers interact with one another and these interactions have significant influences (Martin & Fabes, 2001). The present research helps to address this gap and our results call for more efforts in this area.

In addition, it will be important to examine peer play and its correlates with children from a wide range of backgrounds, given that cultural differences in play socialization and parent-involvement in play (Rogoff et al., 1993), as well as in children's social interaction organization (Mejía-Arauz, Rogoff, Dexter, & Najafi, 2007), have been identified. There may be cultural differences in play with peers and/or in the manner in which play relates to school competence. For instance, observer-rated play interaction has been found to be higher for Hispanic than African-American Head Start children (albeit the reverse was found for teachers' reports; Milfort & Greenfield, 2002).

Our results have important implications for educational reform related to Head Start and school readiness. For years now, academic scholars, policy makers, and practitioners have engaged in serious debates regarding the most important school readiness skills, particularly for children at risk. The findings of the present study highlight the importance of peer interactions as significant predictors of kindergarten adjustment for Head Start children, and remind us of the importance of young children's play with their peers and their long-term influences. Head Start programs should foster children's peer interactions and the skills associated with these prior to elementary school (Fantuzzo, Sekinio, & Cohen, 2004). Moreover, educators and parents may want to directly teach social skills to at-risk children and pay attention to peer play in Head Start children. It is possible that paying attention to, and targeting, potential sources of shifts in peer play behavior (e.g., negative peer treatment, anxiety) may help prevent Head Start children's problems when they enter formal schooling.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

Head Start preschoolers' peer play increased over time during preschool on average

There were significant individual differences in peer play trajectories

More peer play at the start of preschool predicted kindergarten school competence

Increases in preschool peer play predicted kindergarten school competence

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to Fabes, Hanish, and Martin (1 R01 HD45816-01A1). Research support for this project also was provided by the Cowden Endowment Fund. The authors would like to thank the students who contributed to this project, as well as the children and teachers for their participation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bakeman R, Brownlee JR. The strategic use of parallel play: A sequential analysis. Child Development. 1980;51:873–878. doi:10.2307/1129476. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Oxford, England: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barth JM, Parke RD. Parent-child relationship influences on children's transition to school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1993;39:173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher-child relationship and children's early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(96)00029-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z. Selective imitation of same-age, older, and younger peer models. Child Development. 1981;52:717–720. doi:10.2307/1129197. [Google Scholar]

- Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Manz PH, Mendez JL, McWayne CM, Sekino Y, Fantuzzo JW. Peer play interactions and readiness to learn: A protective influence for African American preschool children from low-income households. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:225–231. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00221.x. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Nelson LJ, Rubin KH. Nonsocial play as a risk factor in social and emotional development. In: Göncü A, Klein EL, editors. Children in play, story, and school. Guilford Press; NY: 2001. pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens A, Duncan G, Engel M. Kindergarten skills and fifth-grade achievement: Evidence from the ECLS-K. Economics of Education Review. 2009;28:415–427. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.09.003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JS, Mendez JL. Emotion regulation, language ability, and the stability of preschool children's peer play behavior. Early Education and Development. 2009;20:1016–1037. doi:10.1080/10409280903305716. [Google Scholar]

- Coolahan K, Fantuzzo J, Mendez J, McDermott P. Preschool peer interactions and readiness to learn: Relationships between classroom peer play and learning behaviors and conduct. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:458–465. doi:I:I0.1037MXI22-0663.92.3.45. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA. Peer interactions and play in early childhood. In: Rubin KH, Bukowksi WM, Laursen B, editors. Social, emotional, and personality development in context. The Guilford Press; NY: 2009. pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, McKinley M, Couchoud EA, Holt R. Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child Development. 1990;61:1145–1152. doi:10.2307/1130882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Dowsett CJ, Claessens A, Magnuson K, Huston AC, Klebanov P, Brooks-Gunn J. School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3rd ed. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Padilla ER, Lugo DE, Dunn LM. Test de Vocabulario en Imagenes Peabody: TVIP: Adaptacion Hispanoamericana (Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test: PPVT: Hispanic-American Adaptation) American Guidance Service, Inc.; Circle Pines, MN: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Elias CL, Berk LE. Self-regulation in young children: Is there a role for sociodramatic play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17:216–238. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(02)00146-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Hanish LD, Martin CL, Eisenberg N. Young children's negative emotionality and social isolation: A latent growth model analysis. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48:284–307. doi:10.1353/mpq.2002.0012. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Martin CL, Hanish LD, Anders MC, Madden-Derdich DA. Early school competence: The roles of sex-segregated play and effortful control. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:848–858. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.848. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Coolahan K, Mendez J, McDermott P, Sutton-Smith B. Contextually-relevant validation of peer play constructs for African American Head Start Children: Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1998;13:411–431. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(99)80048-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Sekino Y, Cohen HL. An examination of the contributions of interactive peer play to salient classroom competencies for urban head start children. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Farran DC, Son-Yarbrough W. Title I funded preschools as a developmental context for children's play and verbal behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2001;16:245–262. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00100-4. [Google Scholar]

- Farver JM, Xu Y, Eppe S, Lonigan CJ. Home environments and young Latino children's school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:196–212. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.008. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EP. The impact of play on development: A meta-analysis. Play and Culture. 1992;5:159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo C, Fuller B. The social competence of Latino kindergartners and growth in mathematical understanding. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:579–592. doi: 10.1037/a0017821. doi:10.1037/a0017821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE. Parenting and academic socialization as they relate to school readiness: The roles of ethnicity and family income. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2001;93:686–697. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.4.686. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Social competency with peers: Contributions from child care. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1987;2:155–167. doi:10.1016/0885-2006(87)90041-X. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Peer interaction of young children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1988;53:1–92. doi:10.2307/1166062. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. The collaborative construction of pretend: Social pretend play functions. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson CC. Sequences in the development of competent play with peers: Social and social pretend play. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:961–974. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.961. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Ershler J. Developmental trends in preschool play as a function of classroom program and child gender. Child Development. 1981;52:995–1004. doi:10.2307/1129104. [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer MJ. Catching up or falling behind? Initial English proficiency, concentrated poverty, and the reading growth of language minority students in the United States. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:851–868. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.4.851. [Google Scholar]

- La Paro KM, Pianta RC. Predicting children's competence in the early school years: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research. 2000;70:443–484. doi:10.3102/00346543070004443. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Children's peer relations and social competence: A century of progress. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Price JM. Predicting children's social and school adjustment following the transition from preschool to kindergarten. Child Development. 1987;58:1168–1189. doi:10.2307/1130613. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard AS, Lerner MD, Hopkins EJ, Dore RA, Smith ED, Palmquist CM. The impact of pretend play on children's development: A review of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:1–34. doi: 10.1037/a0029321. doi:10.1037/a0029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love JM, Logue ME, Trudeau JV, Thayer K. Transitions to kindergarten in American schools: Final report of the national transition study. RMC Research Corporation; Portsmouth, NH: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Maas CJM, Hox JJ. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology. 2005;1:86–92. doi:10.1027/1614-1881.1.3.86. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Fabes RA. The stability and consequences of young children's same-sex peer interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:431–446. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Pianta RC. Social relationships and school readiness. Early Education, & Development. 2006;17:151–176. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1701_7. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWayne CM, Cheung K, Green Wright LE, Hahs-Vaughn DL. Patterns of school readiness among head start children: Meaningful within-group variability during the transition to kindergarten. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2012;104:862–878. doi:10.1037/a0028884. [Google Scholar]

- Meisels SJ. Performance in context: Assessing children's achievement at the outset of school. In: Sameroff AJ, Haith MM, editors. The five to seven year shift. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1996. pp. 407–431. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía-Arauz R, Rogoff B, Dexter A, Najafi B. Cultural variation in children's social organization. Child Development. 2007;78:1001–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01046.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milfort R, Greenfield DB. Teacher and observer ratings of Head Start children's social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17:581–595. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(02)00190-4. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 7th ed Author; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics The condition of education 2010. 2010 (Rep. No. NCES 2010–028). Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2010/2010028.pdf.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.) Child Development and Behavior Branch Early childhood education and school readiness: Conceptual models, constructs, and measures: Workshop summary. 2002 Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/documents/school_readiness.pdf.

- Nielsen M, Moore C, Mohamedally J. Young children overimitate in third-party contexts. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parten MB. Social participation among pre-school children. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1932;27:243–269. doi:10.1037/h0074524. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB, Vaden NA. Income level, gender, ethnicity, and household composition as predictors of children's school-based competence. Child Development. 1990;61:485–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02794.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Stuhlman MW. Teacher-child relationships and children's success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review. 2004;33:444–458. [Google Scholar]

- Provost MA, LaFreniere PJ. Social participation and peer competence in preschool children: Evidence for discriminant and convergent validity. Child Study Journal. 1991;21:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Knitzer J. National Center for Children in Poverty. Colombia University, Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY: 2002. Ready to enter: What research tells policymakers about strategies to promote social and emotional school readiness among three- and four-year-olds. Retrieved from http://nccp.org/publications/pub_485.html. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter J, Yunik G. Social interaction in nursery schools. Developmental Psychology. 1973;9:319–325. doi:10.1037/h0034984. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Pianta RC. An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: A theoretical framework to guide empirical research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21:491–511. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(00)00051-4. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Anderson GT, Porter CL, Hart CH, Wouden-Miller M. Sequential transition patterns of preschoolers' social interactions during child-initiated play: Is parallel-aware play a bidirectional bridge to other play states? Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2003;18:3–21. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(03)00003-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B, Mistry J, Goncu A, Mosier C, Chavajay P, Heath SB. Guided participation in cultural activity by toddlers and caregivers. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1993;58:1–179. doi:10.2307/1166109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH. Play observation scale. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.rubin-lab.umd.edu/Coding%20Schemes/POS%20Coding%20Scheme%202001.pdf.