Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether letrozole incorporated in a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist multiple dose protocol (MDP) improved controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) and in vitro fertilization (IVF) results in poor responders who underwent IVF treatment.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, a total of 103 consecutive IVF cycles that were performed during either the letrozole/GnRH antagonist MDP cycles (letrozole group, n=46) or the standard GnRH antagonist MDP cycles (control group, n=57) were included in 103 poor responders. COS results and IVF outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Results

Total dose and days of recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone (rhFSH) administered were significantly fewer in the letrozole group than in the control group. Duration of GnRH antagonist administered was also shorter in the letrozole group. The number of oocytes retrieved was significantly higher in the letrozole group. However, clinical pregnancy rate per cycle initiated, clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer, embryo implantation rate and miscarriage rate were similar in the two groups.

Conclusion

The letrozole incorporated in GnRH antagonist MDP may be more effective because it results comparable pregnancy outcomes with shorter duration and smaller dose of rhFSH, when compared with the standard GnRH antagonist MDP.

Keywords: Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist, In vitro fertilization, Letrozole, Poor responder

Introduction

Although many studies have been performed to develop a method of efficient controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) in infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve who are scheduled for in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, the management for them remains challenging. Several COS regimes have been developed, including the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist low-dose long protocol [1,2], GnRH agonist flare-up regimes [3,4], and GnRH antagonist protocols [5,6,7]. However, none of these protocols have been particularly effective in improving the ovarian response of poor responders. Therefore, hormonal manipulation that aim to augment follicular recruitment and coordinate subsequent antral follicle growth during COS has been used in poor responders. Such hormonal manipulation involves the use of aromatase inhibitors.

Indeed, several preliminary studies showed that when the aromatase inhibitor letrozole is added to a COS protocol in poor responders, the ovarian response to follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) improves and total doses of gonadotropin required are reduced [8,9,10,11].

Therefore, the present study was performed to evaluate whether letrozole incorporated in a GnRH antagonist multiple dose protocol (MDP) would improve the ovarian response to COS and IVF results in poor responders who underwent IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Materials and methods

1. Patients

This retrospective cohort study included 103 consecutive IVF/ICSI cycles in 103 poor responders who underwent COS using either the GnRH antagonist MDP in which letrozole is added (letrozole group, n=46) or the standard GnRH antagonist MDP (control group, n=57) between January 2008 and December 2011. The diagnosis of poor responder was based on the Bologna criteria of the 2011 European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology consensus [12]. Twenty-five patients of all subjects have previously undergone ovarian surgery for ovarian cysts. Twelve patients of them were included in the letrozole group and 13 were included in the control group. Twelve patients with the result that less than 4 oocytes were retrieved despite the use of an ovarian stimulation protocol of at least 150 IU FSH per day in a previous failed IVF/ICSI cycle were included in this study. Six patients of twelve were included in each the letrozole group and control group. The institutional review board of the University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, approved the study.

The selection criteria for this study were as follows: 1) women of 20 to 39 years old, 2) women with normal ovulatory cycles of 24 to 35 days in length, 3) body mass index (BMI) between 18 and 25 kg/m2, and 4) women without any endocrine and metabolic disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes and thyroid dysfunction. Patients were excluded from this study if they were found to have any significant pelvic pathology such as hydrosalpinx, uterine anomaly, advanced endometriosis of stage III to IV or fibroids with uterine cavity distortion. Subjects who had any abnormalities that would interfere with adequate stimulation, previous hospitalization due to severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, or a history of previous (within 12 months) or current abuse of alcohol or drugs were also excluded. If patients underwent two or more cycles of IVF/ICSI during the study period, charts corresponding to the 1st IVF/ICSI cycle were reviewed and data of other IVF/ICSI cycles except 1st cycle were excluded from this analysis.

2. Controlled ovarian stimulation protocols

In the letrozole group, letrozole (Femara, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) 2.5 mg per os daily was administered from the 3rd day to 7th day of menstruation after ovarian and uterine quiescence was established by transvaginal ultrasound. From the 3rd day of letrozole treatment (stimulation day 3), 225 IU of recombinant human FSH (rhFSH; Gonal-F, Merck Serono, Geneva, Switzerland) was initiated. In the control group, 225 IU of rhFSH was commenced from the 3rd day of menstruation after establishing ovarian and uterine quiescence. In both groups, the dose of rhFSH was adjusted according to ovarian response, every 3 to 4 days. When the lead follicle reached 13 to 14 mm in average diameter, GnRH antagonist cetrorelix (Cetrotide, Merck Serono) at a dose of 0.25 mg/day was started and continued daily up to the day of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) injection. A recombinant hCG (rhCG; Ovidrel, Merck Serono) of 250 µg was administered subcutaneously simultaneously with GnRH agonist 0.1 mg (Decapeptyl; Ferring, Malmo, Sweden) to induce follicular maturation when one or more follicles reached a mean diameter of ≥18 mm.

In both groups, transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval was performed 36 hours after rhCG injection. After IVF or ICSI, one to four embryos were transferred into the uterus on the 3rd day after oocyte retrieval. Luteal support was provided by administering 90 mg of vaginal progesterone gel (Crinone gel 8%, Merck Serono) once daily from the day of oocyte retrieval. The β-hCG serum levels were measured by radioimmunoassay using a hCG MAIA clone kit (Serono Diagnostics, Woking, UK) with interassay and intraassay variances of <10% and 5%, respectively,11 days after embryo transfer (ET). Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of a gestational sac by ultrasonography, while miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy was defined as the proportion of patients who failed to continue development before 20 weeks of gestation in all clinical pregnancies.

3. Statistical analysis

Mean values were expressed as mean±standard deviation. Student's t-test was used to compare mean values. Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare fraction. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All analyses were performed by using SPSS ver. 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

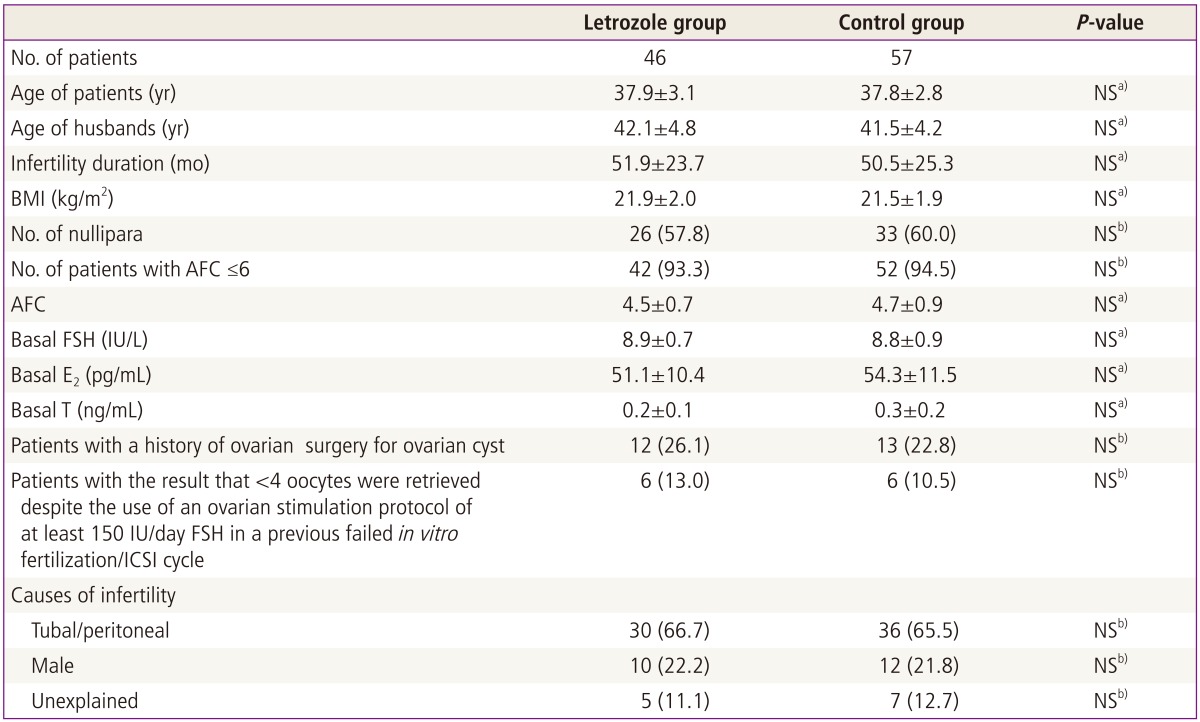

The two groups did not differ with respect to the ages of the patients and their spouses, duration of infertility, BMI, the proportion of nullipara, antral follicle count (AFC), basal endocrine profile and IVF/ICSI indications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Values are mean±standard deviation or n (%).

NS, not significant; BMI, body mass index; AFC, antral follicle count; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; T, testosterone; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

a)Student's t-test; b)Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

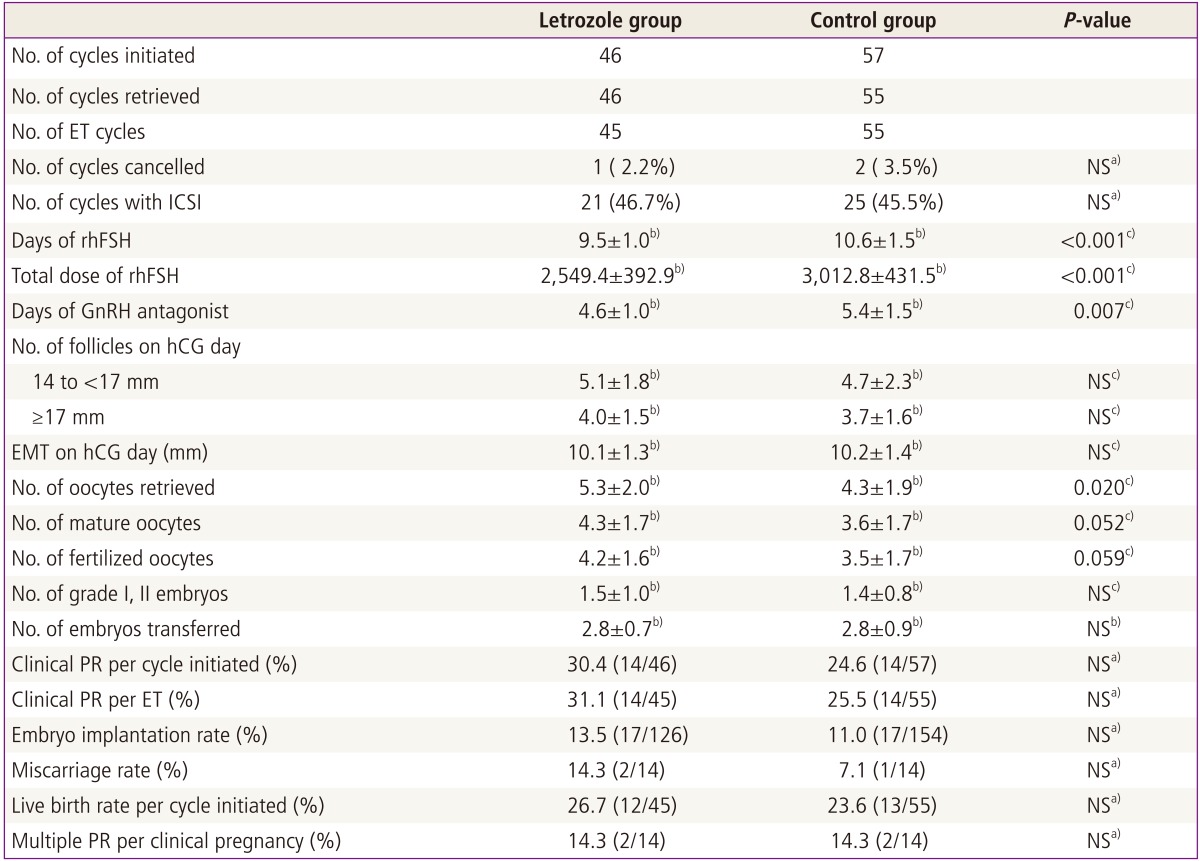

In the letrozole group, 1 out of 46 cycles initiated (2.2%) was cancelled before ET, because no oocytes were obtained despite a follicular aspiration for oocyte retrieval. In the control group, 2 out of 57 cycles initiated (3.5%) was cancelled before oocyte retrieval due to no follicular development. There was no difference in cycle cancellation rate between the two groups (Table 2). Compared with the control group, the letrozole group had a significantly shorter duration of rhFSH administration for COS (P<0.001) and required significantly less total dose of rhFSH (P<0.001) (Table 2). The number of oocytes retrieved was significantly higher in the letrozole group of 5.3±2.0, compared with 4.3±1.9 in the control group (P<0.020). However, there were no significant differences in the numbers of mature oocytes, fertilized oocytes and grade I or II embryos between the two groups (Table 2). The clinical pregnancy rates per cycle initiated and per cycle ET, embryo implantation rate, miscarriage rate, and live birth rate per cycle initiated were comparable in the two groups (Table 2). No patients reported any systemic or local adverse effects attributed to the use of letrozole.

Table 2.

Comparison of controlled ovarian stimulation results and in vitro fertilization/ICSI outcome

ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; ET, embryo transfer; NS, not significant; rhFSH, recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; EMT, endometrial thickness; PR, pregnancy rate; ET, embryo transfer.

a)Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test; b)Mean±standard deviation; c)Student's t-test.

Discussion

Approximately 9% to 30% of infertile women that undergo assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) are poor responders with diminished ovarian reserve (DOR). Poor ovarian response to COS is still a major concern in IVF/ICSI treatment. Especially, the growing tendency of women to postpone childbearing until their late 30's or early 40's significantly decreases their chance of achieving a pregnancy and increases the incidence of poor ovarian response to COS. The most important objective in managing poor responders whose IVF cycles fail repeatedly is to increase ovarian sensitivity to gonadotropin. This is likely to improve pregnancy outcomes and reduce the high cost of IVF overall.

Recently, aromatase inhibitors were found to elevate follicular sensitivity to gonadotropin effectively, which makes them useful in the management of infertility [8,9,10,11,13]. Aromatase inhibitors inhibit the enzyme by competitively binding to the heme of the cytochrome P450 subunit. This blocks androgen conversion into estrogen, thus causing a temporary accumulation of intraovarian androgens [13]. Androgen promotes the initiation of primordial follicle growth and increases the number of growing preantral and small antral follicles in the primate ovary [14,15]. Howles et al. [16] also suggested that, in women with DOR who undergo ART treatment, boosting intraovarian androgens may increase the number of small antral follicle available to enter the recruitment stage as well as the process of follicle recruitment itself. In addition, androgen accumulation in the follicle may also stimulate insulin-like growth factor I, which may synergize with FSH to promote folliculogenesis [17,18]. Kim et al. [19] and Kim [20] investigated whether androgen treatment affects ovarian features. Their study demonstrated that both 3 weeks and 4 weeks transdermal testosterone gel pretreatment result in the significant increase of AFC and significant decreases of mean follicular diameter and resistance index value of ovarian stromal artery, compared with baseline values.

In 2002, Mitwally and Casper [8] reported the results of an observational cohort study that included women with unexplained infertility who were undergoing COS and intrauterine insemination. The subjects were divided into three groups that were assigned to receive the FSH protocol alone (FSH only group), letrozole plus the FSH protocol (letrozole/FSH group), or clomiphene citrate (CC) plus the FSH protocol (CC/FSH group). The letrozole/FSH and CC/FSH groups required significantly lower total FSH doses than the FSH only group. However, pregnancy rates were significantly higher in the letrozole/FSH and FSH only groups than in the CC/FSH group. Thus, they concluded that aromatase inhibition with letrozole reduces the FSH dose required for COS and does not have the undesirable antiestrogenic effects that are frequently seen in women who take CC [8]. The success of letrozole in increasing ovarian sensitivity to gonadotropins encouraged further exploration of the ability of letrozole to improve the response to ovarian stimulation in poor responders. Recent studies again found that the addition of letrozole improved the ovarian response to FSH and reduced the gonadotropin dose needed for COS in poor responders [9,10,11]. Goswami et al. [11] performed a randomized controlled single-blind trial to evaluate the effect of the adjunctive use of letrozole in 38 poor responders. In their study, subjects were randomly assigned to the GnRH agonist long protocol or the letrozole plus FSH protocol during IVF cycles. Their study showed that the letrozole/FSH group had comparable pregnancy outcomes with lower total dose of FSH required, compared with the GnRH agonist long protocol group [11].

In the present study, letrozole was incorporated in GnRH antagonist MDP during IVF/ICSI cycles and its efficacy was compared with the standard GnRH antagonist MDP. The addition of letrozole yielded comparable pregnancy outcome with significantly fewer dose and days of rhFSH required even in GnRH antagonist MDP. Although the criteria for GnRH antagonist initiation were same in both letrozole and control groups, duration of GnRH antagonist administration was significantly shorter in the letrozole group than in the control group. Letrozole increases ovarian sensitivity to gonadotropins, thereby improving ovarian response to rhFSH and significantly reducing the duration of rhFSH administration. This action of letrozole may contribute to decrease the duration of GnRH antagonist use in the letrozole group. Moreover, letrozole supplementation resulted in a significant increase of the number of oocytes retrieved. When considering that GnRH antagonist protocol is recently recognized as one of promising COS regimen for poor responders, our results are encouraging. Studies comparing letrozole/GnRH antagonist protocol with standard GnRH antagonist protocol are very limited. Only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Ozmen et al. [21] was found. The results of their study were similar to those of our retrospective cohort study. In both studies, the total dose of gondotropin required for COS was significantly lower in the letrozole group and clinical pregnancy rate per ET cycle was comparable between the letrozole and control groups. In the study by Ozmen et al. [21], rhFSH was administered with a fixed dose (450 IU/day) in both study and control groups. However, rhFSH was administered with a flexible manner in our study. In the present study, the starting dose of rhFSH was 250 IU/day which was much smaller than the daily dose of rhFSH used in the RCT by Ozmen et al. [21] and the dose of rhFSH was adjusted according to ovarian response, every 3 to 4 days. The total dose of rhFSH used in each letrozole and control groups in our study appeared to be lower, when compared with those in the study by Ozmen et al. [21]. It may be caused by the difference of gonadotropin administration method between their RCT and our study.

Our results suggest that GnRH antagonist MDP in which letrozole is incorporated may be more effective than standard GnRH antagonist MDP in poor responders undergoing IVF/ICSI. However, our study has a limitation to evaluate the efficacy of letrozole addition due to a small number of sample available and its retrospective nature. In the near future, well-designed prospective randomized trials are required to confirm the efficacy of letrozole as an adjuvant to gonadotropin in COS for poor responders.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Feldberg D, Farhi J, Ashkenazi J, Dicker D, Shalev J, Ben-Rafael Z. Minidose gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist is the treatment of choice in poor responders with high follicle-stimulating hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivennes F, Righini C, Fanchin R, Torrisi C, Hazout A, Glissant M, et al. A protocol using a low dose of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist might be the best protocol for patients with high follicle-stimulating hormone concentrations on day 3. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1169–1172. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padilla SL, Dugan K, Maruschak V, Shalika S, Smith RD. Use of the flare-up protocol with high dose human follicle stimulating hormone and human menopausal gonadotropins for in vitro fertilization in poor responders. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:796–799. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surrey ES, Bower J, Hill DM, Ramsey J, Surrey MW. Clinical and endocrine effects of a microdose GnRH agonist flare regimen administered to poor responders who are undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olivennes F, Belaisch-Allart J, Emperaire JC, Dechaud H, Alvarez S, Moreau L, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled study of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer with a single dose of a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) antagonist (cetrorelix) or a depot formula of an LH-RH agonist (triptorelin) Fertil Steril. 2000;73:314–320. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolibianakis EM, Collins J, Tarlatzis BC, Devroey P, Diedrich K, Griesinger G. Among patients treated for IVF with gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues, is the probability of live birth dependent on the type of analogue used? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:651–671. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim CH, Jeon GH, Cheon YP, Jeon I, Kim SH, Chae HD, et al. Comparison of GnRH antagonist protocol with or without oral contraceptive pill pretreatment and GnRH agonist low-dose long protocol in low responders undergoing IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1758–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibition improves ovarian response to follicle-stimulating hormone in poor responders. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:776–780. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of infertility. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:353–371. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healey S, Tan SL, Tulandi T, Biljan MM. Effects of letrozole on superovulation with gonadotropins in women undergoing intrauterine insemination. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1325–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goswami SK, Das T, Chattopadhyay R, Sawhney V, Kumar J, Chaudhury K, et al. A randomized single-blind controlled trial of letrozole as a low-cost IVF protocol in women with poor ovarian response: a preliminary report. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2031–2035. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L, et al. ESHRE consensus on the definition of 'poor response' to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Velasco JA, Moreno L, Pacheco A, Guillen A, Duque L, Requena A, et al. The aromatase inhibitor letrozole increases the concentration of intraovarian androgens and improves in vitro fertilization outcome in low responder patients: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vendola KA, Zhou J, Adesanya OO, Weil SJ, Bondy CA. Androgens stimulate early stages of follicular growth in the primate ovary. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2622–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vendola K, Zhou J, Wang J, Famuyiwa OA, Bievre M, Bondy CA. Androgens promote oocyte insulin-like growth factor I expression and initiation of follicle development in the primate ovary. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:353–357. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howles CM, Kim CH, Elder K. Treatment strategies in assisted reproduction for women of advanced maternal age. Int Surg. 2006;91(5 Suppl):S37–S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adashi EY. Intraovarian regulation: the proposed role of insulin-like growth factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;687:10–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giudice LC. Insulin-like growth factors and ovarian follicular development. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:641–669. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-4-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CH, Ahn JW, Nah HY, Kim SH, Chae HD, Kang BM. Ovarian features after 2 weeks, 3 weeks and 4 weeks transdermal testosterone gel treatment and their associated effect on IVF/ICSI outcome in low responders. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4 suppl):S155–S156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CH. Androgen supplementation in IVF. Minerva Ginecol. 2013;65:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozmen B, Sonmezer M, Atabekoglu CS, Olmus H. Use of aromatase inhibitors in poor-responder patients receiving GnRH antagonist protocols. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]