Abstract

Various approaches have been studied to engineer the implant surface to enhance bone in-growth properties, particularly using micro- and nano- topography. In this study, the behavior of osteoblast (bone) cells was analyzed in response to a titanium oxide (TiO2) nanotube-coated commercial zirconia femoral knee implant consisting of a combined surface structure of a micro-roughened surface with the nanotube coating. The osteoblast cells demonstrated high degrees of adhesion and integration into the surface of the nanotube-coated implant material, indicating preferential cell behavior on this surface when compared to the bare implant. The results of this brief study provide sufficient evidence to encourage future studies. The development of such hierarchical micro and nano topographical features, as demonstrated in this work, can provide for insightful designs for advanced bone-inducing material coatings on ceramic orthopedic implant surfaces.

Keywords: TiO2 nanotube, osteoblast, orthopedic implant, zirconia, cell adhesion, osseointegration

INTRODUCTION

Zirconia (ZrO2) was introduced as an orthopedic implant material in 1985, and is well known as one of the highest-strength ceramics suitable for medical use [1]. In particular, zirconia has been found to be a choice material for the femoral component of the total knee implant when compared to the more commonly used CoCr, due to a reduction in polyethylene wear [2]. Although zirconia orthopedic implants received a poor reputation in the late 90s due to failures found to be a result of a change in the heat treatment procedure, a much better understanding of the ceramic aging and degradation behavior and prevention techniques has been obtained [3–4], and the material is becoming popular again.

While the current success of total knee replacement (TKR) is much improved from pioneering knee implant designs, further improvements are necessary for increased implant lifetime. Some studies have shown that the failure rate of TKR is greater in younger patients due to a higher level of activity [5]. The most common reasons for TKR revision surgery are aseptic loosening and instability [6]. The reasons for aseptic loosening are multifactorial [7]. However, in general, the source of the problem lies in osteolysis at the bone-implant interface. As such, one area for implant lifetime improvement is in strengthening the osseointegration of the implant.

Zirconia implant surfaces are chemically inert, and do not naturally form a bond with bone [8], thus cemented fixation is required. There is much controversy on the benefits of cemented versus uncemented fixation techniques of TKRs. Uncemented fixation for TKR was introduced as a method of potentially increasing implant longevity [9]. The presence of a more physiological bond between the bone and the implant is considered by some to provide a stronger device [10]. While studies in the literature often favor cemented fixation, some more recent studies suggest that there is not a significant difference between the fixation methods [10–11], and both are equally recommended in terms of implant performance. In any case, current studies investigating methods for modifying the surface properties of zirconia with the aim to achieve osseointegration naturally without the use of a bone cement. One such study utilized a CO2 laser to introduce microstructure and higher surface energy to the surface of zirconia ceramic, which resulted in enhanced bone cell adhesion to the surface [8].

It has been well-established that the presence of nanotopography affects basic cell behavior in almost all types of mammalian cells [12]. Of particular interest are titanium oxide (TiO2) nanotubes, since titanium is a well-known biocompatible orthopedic material. TiO2 nanotubes have been found not only to significantly accelerate osteoblast cell growth, but also improve bone-forming functionality and direct stem cell fate. These results are especially promising for well-established titanium bone implants currently on the market, since aseptic loosening is still a relevant problem in orthopedic implants. The nanotube surface structure can essentially be added to any shape of titanium implant by a simple anodization procedure. Additionally, TiO2 nanotubes can be grown from a thin film of titanium deposited onto another surface. This expands the possible applications to not only current titanium implants, but other types of implants as well.

In this work, a commercial zirconia ceramic femoral knee component was sputter coated with a thin film of titanium on the bone bonding (backside) surface, and further anodized to form a coating of TiO2 nanotubes. Osteoblast viability, adhesion, and spreading was analyzed and compared on the TiO2 nanotube coating and bare zirconia implant surface. Here we report an improvement of osteoblast cell adhesion and spreading on the TiO2 nanotube coated implant.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Apparatus and Reagents

The apparatus used for TiO2 nanotube fabrication has been described in detail elsewhere [13]. The reagents used for each respective part of the experiment are described in the following sections.

TiO2 Nanotube-Coated Implant Preparation

A zirconia ceramic femoral knee component was obtained from Kinamed, Inc. (GEM™ Total Knee System, Cat # 20-120-1001) and was cleaved into six pieces in a manner which maximized the sample surface area of relatively flat backside implant surface. In order to obtain regular surfaces for the experiments, the prosthesis was cut using a diamond saw into rectangular pieces measuring ~1 cm × 2 cm. The backside of the samples were then ground to create a relatively flat and even surface. Two of the pieces were set aside to be used as controls in this study, while the remaining four pieces were taken for further processing. Before film deposition, ZrO2 implant materials were cleaned successively in acetone and isopropyl alcohol with ultrasonication. Ti thin film was vacuum-deposited using Denton Discovery 18 sputter system. Base pressure was 1~10−6 torr and substrate being rotated was heated to 400 °C during sputtering. Plasma power was 200 W and Ar pressure was 3.0 mTorr. Deposition rate was 0.25 nm/s and 1 μm thick Ti film was deposited. Electrical contact for the anodization step was provided by copper tape and a lacquer protective paint. The TiO2 nanotube surfaces were created using a two-electrode-setup anodization process. An organic-based electrochemical solution was used which was composed of 0.25 wt% NH4F in 2 vol% deionized water in ethylene glycol. A platinum electrode (99.9% pure, Alfa-Aesar, USA) served as the cathode. The samples were anodized at 20 V for 15 min, followed by a washing step with ethanol, and an acetone soak to remove the lacquer paint. The samples were then dried at 80 °C overnight and heat-treated at 500 °C for 2 h in order to crystallize the as-fabricated amorphous structured TiO2 nanotubes into an anatase structure. The samples used for all experiments were sterilized by autoclaving prior to use. The bare zirconia implant samples were used as a control after being chemically cleaned by acetone and isopropanol, dried and autoclaved.

Adhesion Strength Test

For adhesion strength of TiO2 nanotube coating on the zirconia implant materials, a simple adhesion set-up was utilized. Commercial thermosetting epoxy was attached on the surface of the TiO2 nanotubes and a hook-shaped metal wire end was tightly embedded inside the epoxy. The adhered area of epoxy was 0.2 cm2. After the epoxy was fully cured, uniaxial force was applied normal to the surface. Adhesion strength was indirectly determined whether fracture occurred along the epoxy/TiO2 nanotube interface or TiO2 nanotube/implant interface. In result, adhesion strength was at least greater than 460 lb/in2 in which epoxy was detached from TiO2 nanotube surface with a sharp facture interface.

Contact Angle Measurement

The measurement of contact angle for the bare implant and TiO2 nanotube surfaces was carried out by a video contact angle measurement system (Model No. VSA 2500 XE, AST Products, Inc.).

Osteoblast Cell Culture

For this study, MC3T3-E1 mouse osteoblast (CRL-2593, subclone 4, ATCC, USA) were used. Each 1 mL of cells was mixed with 10 mL of alpha minimum essential medium (α-DMEM; Invitrogen, USA) in the presence of 10 vol% bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, USA) and 1 vol.% penicillin-streptomycin (PS; Invitrogen, USA). The cell suspension was plated in a cell culture dish and incubated at 37°C in a 5 vol% CO2 environment. When the concentration of the MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells reached confluency, they were seeded onto the experimental substrate of interest (TiO2 nanotubes or bare implant), which was placed on a 6-well polystyrene plate and stored in a CO2 incubator for 24 and 48 h to observe the cell morphology and adhesion. The concentration of the cells seeded onto the substrate was 1.5 × 105 cells per well.

Cell Viability, Adhesion, and Spreading Test

Fluorescein diacetate (FDA; Sigma, USA) staining was conducted to visualize cell viability and to quantify cell spreading. At 24 h after plating, the cells on the substrates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (1 × PBS) solution (Invitrogen, USA) and incubated for approximately 30 s with FDA stock (5 mg dissolved in 1 mL of acetone) dissolved in PBS (10μl/10mL), and washed once more. The samples were then inverted into new wells, visualized and photographed using a fluorescence microscope with a green filter (DM IRB, Leica Co., USA). Six fields were randomly chosen from each sample. The digital images were stored in a 672 × 512 pixels file and imported to a TIF format. Stored images were imported to ImageJ image processing program for digital analysis. The number of adherent cells were counted in each image. Additionally, the total cell spreading area was quantified.

SEM for Substrate and Cell Morphological Examination

After 24 h of culture, the cells on the substrates were washed with PBS and fixed with 2.5% w/v glutaraldehyde (Sigma, USA) in PBS for 1 h. After fixation, they were washed three times with PBS for 10 min each wash. The cells were then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (50, 75, 90, 100 vol.%) for 30 min each and left in 100% ethanol overnight. The substrates were then dried by a critical point dryer (EMS 850, Electron Microscopy Science Co., USA). Next, the dried samples were sputter-coated with palladium for examination by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The morphology of the TiO2 nanotubes and bare implant as well as that of the adhered cells were observed using an XL30 scanning electron microscope (FEI Co., USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

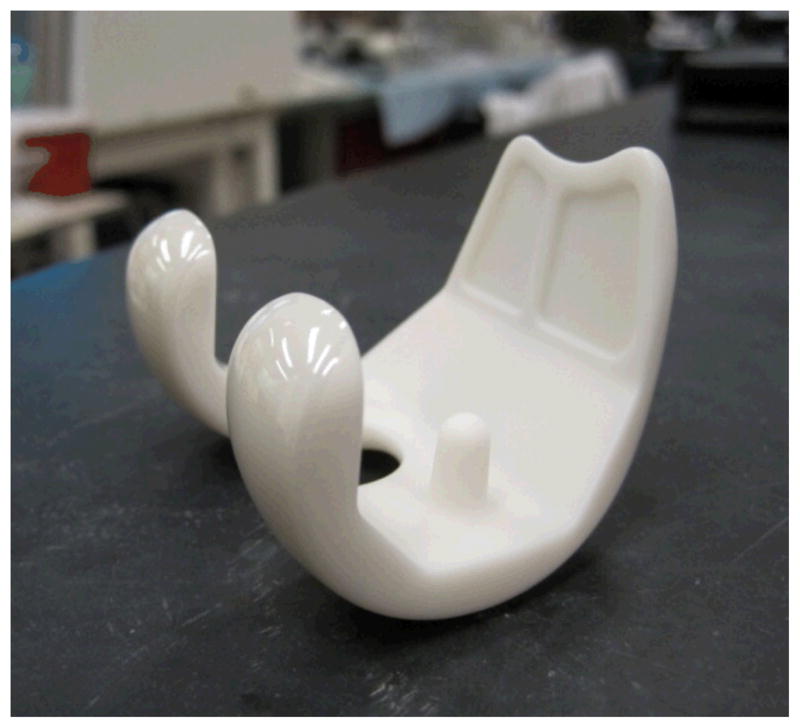

The zirconia (ZrO2) ceramic femoral knee component obtained from Kinamed, Inc. (GEM™ Total Knee System, Cat # 20-120-1001) for modification and experimentation in this study is pictured in Fig. 1, as received. The bone-integrating (backside) surface of the femoral knee implant is shown facing upward (the dull surface) in this photograph, while the articulating (shiny) surface is facing downward. This implant was cut into six sample pieces for use in the study herein.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the as-received commercial zirconia femoral knee implant.

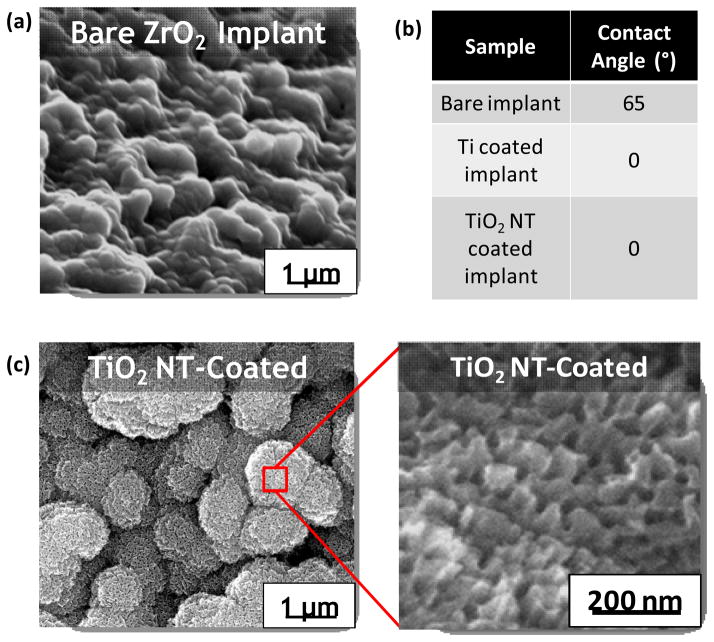

Fig. 2 shows SEM micrographs of the as-received zirconia implant surface (a), and the TiO2 nanotube coated implant surface at low and high magnification (c). Fig. 2(c) reveals the nanotopography present on the TiO2 nanotube surface which is lacking on the bare implant surface (a). The self-assembled nanotube surface was obtained by anodizing the titanium sputter-coated zirconia femoral implant at 20 V an organic-based electrolytic solution. The nanotube pore size is ~50 nm, with a length of ~200 nm.

Figure 2.

Physical characterization of the as-received zirconia implant and TiO2 nanotube coated implant surfaces. (a) SEM micrographs of bare implant surface (tilted 45° angle). (b) Table with surface contact angle measurements of water droplets on the bare implant, titanium coated implant, and TiO2 nanotube coated implant surfaces. (c) SEM micrographs of the TiO2 nanotube coated implant surface at low magnification (left), and high magnification (right).

While the top-view of the TiO2 nanotube surface appears slightly more porous in nature, tube morphology was verified to be present underneath a porous top layer, as seen in Fig. 2(c). This configuration of TiO2 nanotubes with a porous surface morphology was clearly explained by Wang, et al. to be the result of an imbalance in two competitive reactions which occur during TiO2 nanotube formation [14]. Further optimization of our anodization conditions could result in a tube-like surface morphology. However, for the purposes of this study we analyzed the porous TiO2 nanotube surface morphology in comparison with the bare implant material.

The SEM images show that a micron-scale surface roughness is present on the as-received implant; the nanotube coated implant possesses the same microtopography, in addition to the nanotopography created by the porous nanotube surface. The surface contact angle measurements of water droplets on each surface revealed that the titanium surface coating altered the as-received implant surface to become extremely hydrophilic in nature, while the as-received implant was only slightly hydrophilic. The TiO2 nanotube coated implant was also superhydrophilic, with a contact angle of 0° (Fig. 2(b)).

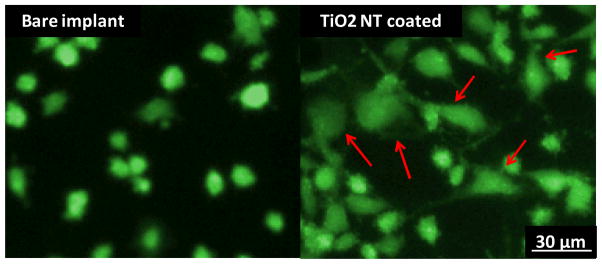

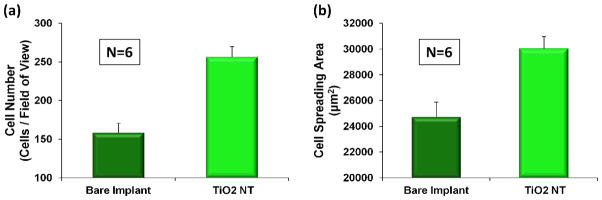

To investigate cell behavior in response to the as-received and modified implant surfaces, osteoblast cells were seeded on the comparative surfaces at a cell density of 1.5 × 105 per well. As indicated in Fig. 3, cell adhesion and spreading after 24 h of culture was found to be increased on the TiO2 nanotube surface in comparison to the bare implant surface. The plots of the quantification of the fluorescent images (Fig. 4) clearly confirm these trends. Both the number of adhered cells (Fig. 4(a)) and cell spreading area (Fig. 4(b)) were significantly increased on the nanotube surface. These results are in agreement with our previously reported investigations of osteoblast behavior on TiO2 nanotube surfaces when compared to flat Ti foil [15–16]. It is likely that the increase in cell adhesion and spreading is a direct result of the superhydrophilic nature of the nanotube-coated surface. Many researchers have demonstrated the positive effects of superhydrophilic biomaterials on protein and cell adhesion properties [17–18].

Figure 3.

FDA viability of osteoblast cells after 24 hours of incubation on the bare zirconia implant and TiO2 nanotube coating on the zirconia implant. More spreading is evident on the nanotube surface which indicates greater cell adhesion. Red arrows indicate significant cell spreading.

Figure 4.

Cell number (a) and spreading area (b) after 24 hours of incubation. The bar graphs show the average ± standard error bars. The p-value after performing a t-test confirmed a statistical significance (p < 0.005).

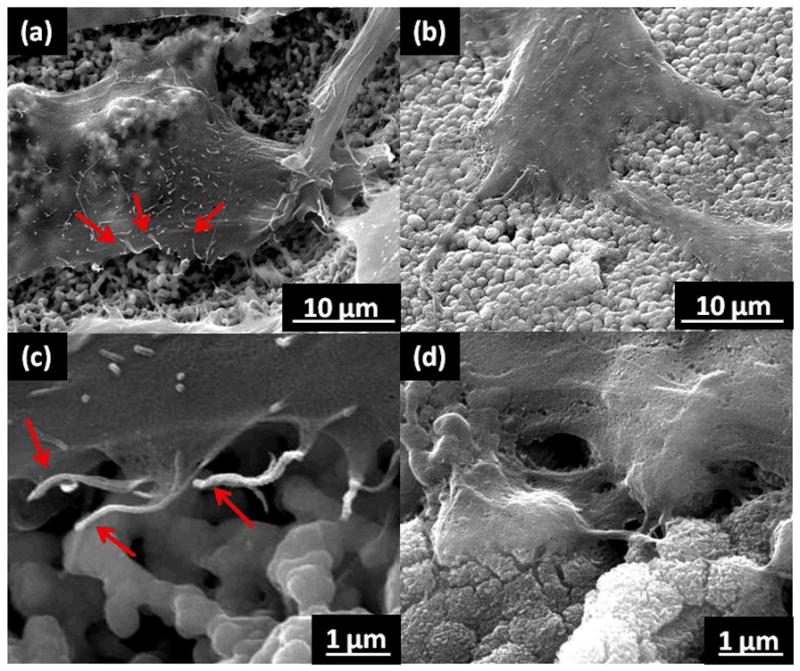

The higher degree of cell adhesion and spreading was further confirmed by SEM, as shown in Fig. 5. On the bare zirconia implant surface (Fig. 5(a) and (c)), the cells appear to be unable to attach to the surface. Although there are many filopodial extensions present, rarely are they in contact with the surface, as indicated by the red arrows. In contrast, the cells on the TiO2 nanotube coated implant surface (Fig. 5(b) and (d)) are clearly integrating into the surface, and no floating filipodia are evident. The higher magnification images of the cell edge (Fig. 5(c) and (d)) emphasize the unmistakable cell-surface interaction evident on the TiO2 nanotube coated implant. It can be speculated that the increase in cell-surface interaction can be contributed to two key factors. Firstly, as mentioned previously, the alteration from a slightly hydrophobic surface to an extremely hydrophilic surface is likely to enhance cell adhesion and spreading capabilities. Secondly, the presence of nanotopography in addition to the bare implant microtopography may have an impact on how the cells behave. A hierarchical hybrid micro/nano-textured titanium surface has been recently considered to create an improved surface structure for osseointegration [19]. While the nanotopography can be assumed to induce an increase in bone functionality, the microtopography contributes to the mechanical interlocking ability of the surface.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of osteoblast cells after 24 hours of incubation on the bare zirconia implant (a, c), and TiO2 nanotube coating on the zirconia implant (b, d). (c) and (d) are higher magnification of the cell edges on the respective surfaces. Red arrows indicate floating filopodia.

The spectrum of this study was limited by the number of commercial femoral implant samples available at the present time. In order to fully evaluate cell adhesion to the surface, more extensive cell proliferation or cell survival experiments such as MTT or WST should be utilized. In addition, further studies should be performed to verify osteoblast functionality and maturation, as well as mesenchymal stem cell behavior on the surfaces in order to demonstrate the in vitro behavior of the two important cell types present at a bone implant interface. Furthermore, in vivo results should be assessed for more complete materials analysis, as well as surface roughness tests.

CONCLUSION

This study was intended to facilitate the osseointegration of zirconia femoral knee implants by providing a novel hierarchical micro- and nano-structured titanium surface coating which encourages bone cell adhesion and integration. The osteoblast cells demonstrated high degrees of adhesion and integration into the surface of the nanotube-coated implant material, indicating preferential cell behavior on this surface. The results of this brief study provide sufficient evidence to encourage future studies. The development of such hierarchical micro and nano topographical features, as demonstrated in this work, can provide for insightful designs for advanced bone-interfacing material coatings on ceramic orthopedic implant surfaces.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by K. Iwama Endowed Chair fund at UC San Diego and UC Discovery Grant No. ele08-128656/Jin. The authors thank Mr. Clyde Pratt of Kinamed, Inc. for active support of the UC Discovery Program, providing the zirconia femoral knee implants for this work as well as helpful discussions and encouragement of this research.

References

- 1.Clarke IC, et al. Current status of zirconia used in total hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(Suppl 4):73–84. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300004-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsukamoto R, et al. Improved wear performance with crosslinked UHMWPE and zirconia implants in knee simulation. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(3):505–11. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevalier J, Gremillard L, Deville S. Low-temperature degradation of Zirconia and implications for biomedical implants. Annual Review of Materials Research. 2007;37:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaise L, Villermaux F, Cales B. Ageing of zirconia: Everything you always wanted to know. Bioceramics. 2000;192-1:553–556. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gioe TJ, et al. Why are total knee replacements revised?: analysis of early revision in a community knee implant registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(428):100–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paxton EW, et al. The Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry. The Permanente Journal. 2008;12(3):5. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundfeldt M, et al. Aseptic loosening, not only a question of wear: a review of different theories. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(2):177–97. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hao L, Lawrence J, Chian KS. Osteoblast cell adhesion on a laser modified zirconia based bioceramic. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16(8):719–26. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-2608-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett RW. Results of 1,000 Performance knees: cementless versus cemented fixation. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(4):409–13. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi R, et al. Survival and clinical function of cemented and uncemented prostheses in total knee replacement: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(7):889–95. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaw FM, et al. A randomised, controlled trial of cemented versus cementless press-fit condylar total knee replacement. Ten-year survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(5):658–66. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b5.12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(30):5406–15. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mor G, et al. A review on highly ordered, vertically oriented TiO2 nanotube arrays: Fabrication, material properties, and solar energy applications. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells. 2006;90:2011–2075. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, et al. TiO2 Nanotubes with Tunable Morphology, Diameter, and Length: Synthesis and Photo-Electrical/Catalytic Performance. Chemistry of Materials. 2009;21(7):9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh S, et al. Significantly accelerated osteoblast cell growth on aligned TiO2 nanotubes. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2006;78A(1):97–103. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brammer KS, et al. Improved bone-forming functionality on diameter-controlled TiO(2) nanotube surface. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(8):3215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyauchi T, et al. The enhanced characteristics of osteoblast adhesion to photofunctionalized nanoscale TiO2 layers on biomaterials surfaces. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3827–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishizaki T, Saito N, Takai O. Correlation of cell adhesive behaviors on superhydrophobic, superhydrophilic, and micropatterned superhydrophobic/superhydrophilic surfaces to their surface chemistry. Langmuir. 2010;26(11):8147–54. doi: 10.1021/la904447c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L, et al. The influence of hierarchical hybrid micro/nano-textured titanium surface with titania nanotubes on osteoblast functions. Biomaterials. 2010;31(19):5072–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]