Abstract

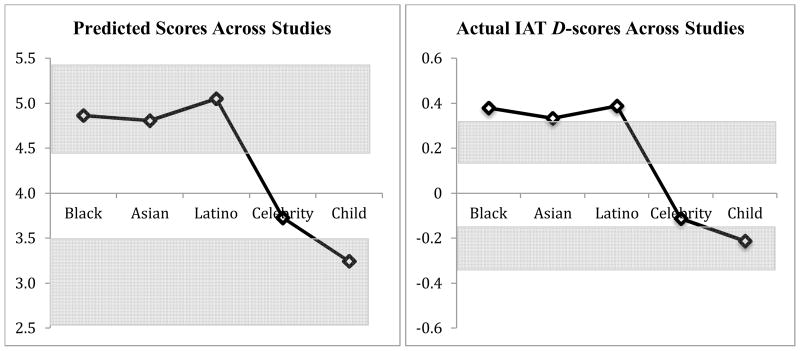

Research on implicit attitudes has raised questions about how well people know their own attitudes. Most research on this question has focused on the correspondence between measures of implicit attitudes and measures of explicit attitudes, with low correspondence interpreted as showing that people have little awareness of their implicit attitudes. We took a different approach and directly asked participants to predict their results on upcoming IAT measures of implicit attitudes toward five different social groups. We found that participants were surprisingly accurate in their predictions. Across four studies, predictions were accurate regardless of whether implicit attitudes were described as true attitudes or culturally learned associations (Studies 1 and 2), regardless of whether predictions were made as specific response patterns (Study 1) or as conceptual responses (Studies 2–4), and regardless of how much experience or explanation participants received before making their predictions (Study 4). Study 3 further suggested that participants’ predictions reflected unique insight into their own implicit responses, beyond intuitions about how people in general might respond. Prediction accuracy occurred despite generally low correspondence between implicit and explicit measures of attitudes, as found in prior research. All together, the research findings cast doubt on the belief that attitudes or evaluations measured by the IAT necessarily reflect unconscious attitudes.

Keywords/phrases: Implicit attitudes, IAT, introspection, unconscious, racial bias

Considerable interest in the concept of implicit attitudes has been shown over the past two decades, both in academic outlets (e.g., Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010; Gawronski & Payne, 2010; Jost, Pelham & Carvallo, 2002; Nosek, Hawkins, & Frazier, 2012; Petty, Fazio, & Brinol, 2008; Quillian, 2008; Wittenbrink & Schwartz, 2007) and in the popular media (Gladwell, 2005; Tierney, 2008a, 2008b; The Economist, 2012; Dateline NBC, 2007; Oprah.com, 2006). The term implicit attitude is generally used to refer to an attitude (evaluation or preference) that is inferred from indirect, performance-based procedures (most popularly the Implicit Association Test [IAT], Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) that avoid the direct influence of deliberative processing. This is in contrast to explicit attitudes, which are measured by self-report and necessarily involve respondents knowing that their attitudes are being assessed.1

Much of the interest in implicit attitudes stems from findings that they capture aspects of human thought and behavior that are not revealed by self-reported explicit attitudes. Correlations between implicit and explicit attitudes are often low (e.g., Nosek, 2005, 2007; Nosek & Hanson, 2008; Nosek & Smyth, 2007; for overviews, see Blair, 2001; Hofmann, Gawronski, Gschwendner, Le, & Schmitt, 2005a; Hoffmann, Geschwendner, Nosek, & Schmitt, 2005b), and studies in a number of domains show that implicit and explicit attitudes explain unique aspects of behavior (e.g., Agerström & Rooth, 2011; Blair et al., 2013; Dempsey & Mitchel, 2010; Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; Fazio, Jackson, Dunton, & Williams, 1995; Galdi, Arcuri, & Gawronski, 2008; Green et al., 2007; Rydell & McConnell, 2006; van den Bergh, Denessen, Hornstra, Voeten, & Holland, 2010; for reviews, see Friese, Hofmann, & Schmitt, 2008; Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009).

Although implicit and explicit attitudes have been distinguished along many dimensions (e.g., Bargh, 1994; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006), in line with the origins of the terminology (cp. footnote 1), awareness seems to be of particular significance, such that unconscious attitudes and implicit attitudes (or conscious attitudes and explicit attitudes) are often used as interchangeable terms (e.g., Bosson, Swann & Pennebaker, 2000; Cunningham, Nazlek & Banaji, 2004; Jost et al. 2002; Phelps et al., 2000; Rudman, Greenwald, Mellott & Schwartz, 1999; Quillian, 2008). Additionally, research showing dissociations between implicit and explicit attitudes has been interpreted as suggestive evidence that implicit attitudes might generally not be available to introspection (e.g., Nosek, 2007). Some researchers have even made stronger statements that implicit attitudes cannot be introspected upon (e.g., Devos, 2008; Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2001; Kihlstrom, 2004; McConnell, Dunn, Austin, & Rawn, 2011; Spalding & Hardin, 1999). Other researchers have argued that people probably do have access to implicit attitudes (e.g., Gawronski, Hofmann, & Wilbur, 2006; Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000; Strack & Deutsch, 2004), often based on the finding that implicit-explicit correlations are consistently above zero, and thus some information about them must be available to conscious awareness (e.g., Gschwendner, Hofmann & Schmitt, 2006; Hofmann at el. 2005a, 2005b).

Importantly, there are several aspects of implicit attitudes of which people might or might not be aware. Gawronski et al. (2006) list three: The attitude’s source, its content, and its impact on behavior. In the current paper we are interested in awareness of an attitude’s content: Are people aware that they have implicit preferences, or biases, for certain attitude targets over others? We argue that answering this question on the basis of correlations between implicit and explicit attitudes is inconsistent with theoretical models on implicit and explicit attitudes (Gawronski et al., 2006). To elucidate this point we turn to Gawronski and Bodenhausen’s (2006) Associative-Propositional Evaluation (APE) model.

Awareness and the Associative-Propositional Evaluation Model

According to the APE model by Gawronski and Bodenhausen (2006), implicit attitudes reflect spontaneous affective reactions to an attitudinal cue, regardless of the perceiver’s beliefs that these reactions are valid or invalid. For example, many White Americans appear to have spontaneous negative reactions to Black Americans, even when that negativity is perceived as invalid (Devine, 1989; Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, 2002).

On the other hand, explicit attitudes (i.e., self-reported preferences) result from an inferential process in which a person tries to validate all of the propositions that are salient or considered relevant at the time the explicit attitude judgment is made. These propositions may reflect specific exemplars that come to mind (e.g., “I really like my Black friend Martin; I like Bill Cosby.”), but may also include other sources, such as values (e.g., “I strive to treat all people equally, regardless of their race or ethnicity”); other relevant knowledge (e.g., “I admire the fight certain groups have fought for their rights”); or self-presentational concerns (e.g., “I shouldn’t say that I have negative feelings towards social groups”). One may also consider spontaneous reactions in propositional form (e.g., “I initially feel uncomfortable when I meet a Black person.”). According to the APE model, an explicit attitude results from, a) decisions about the validity of each salient proposition as a basis for judgment, and b) attempts to maximize consistency among the different propositions (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006; Gawronski, Brochu, Sritharan, & Strack, 2012). As a result, in some cases a person will decide on an explicit attitude that is consistent with the implicit attitude. But in other cases a person might decide that, in line with other propositions such as the examples presented above, the initial reaction is not a valid basis for an explicit attitude and consequently the stated explicit attitude is inconsistent with the person’s implicit attitude.

Importantly, one conclusion to draw from the APE model is that how people answer an explicit attitude question is irrelevant to the question of their awareness of their implicit attitude (Hahn & Gawronski, in press). This is because there are other reasons for implicit and explicit attitudes to misalign than just lack of awareness. Explicit attitude questions ask participants about the attitudes they consider valid, not about their awareness of spontaneously activated reactions (implicit attitudes). As shown in the example above, a person could be entirely aware of his or her implicit attitude, but not report it on an explicit attitude measure due to its inconsistency with other propositions. Implicit-explicit correlations reveal whether people consider their implicit attitudes valid bases for explicit attitudes, not whether they are aware of them.

Previous Research

Notwithstanding these considerations, research addressing people’s awareness of their implicit attitudes has primarily focused on correlations between implicit and explicit attitudes, and specifically on the factors that impact the magnitude of these correlations (Gschwendner at al., 2006; Jordan, Whitfield, & Zeigler-Hill, 2007; Ranganath, Smith, & Nosek, 2008; Richetin, Perugini, Perugini, Adjali, Hurling, 2007; Smith & Nosek, 2011). For example, Jordan et al. (2007) found greater correspondence between implicit and explicit measures of self-esteem for people who scored higher on faith in intuition (i.e., chronically viewing their intuitions as more valid). And Gschwendner et al. (2006) found greater correspondence between implicit and explicit interethnic attitudes for people who scored higher in private self-consciousness, although this only occurred when the participants were told to use their IAT performance to answer the explicit attitude questions (but see Hofmann et al., 2005a, who failed to find any effect of private self-consciousness in their meta-analysis). Studies in which participants are directed to consider their gut feelings or respond more spontaneously to explicit attitude questions also find small increases in correlations between implicit and explicit attitudes (Jordan et al., 2007; Ranganath et al., 2008; Smith & Nosek, 2011). In their meta-analysis, Hofmann et al. (2005a) report average correlations of .28 for affect-focused instructions, as opposed to .18 for cognition-focused instructions.

As the first study to investigate people’s understanding of their performance on an implicit attitude measure, Monteith, Voils and Ashburn-Nardo (2001) found that a majority of participants were aware that they had performed differently across the critical blocks of an IAT measure of implicit race attitudes. Furthermore, participants were more likely to attribute their performance difference to racial bias, the more they thought that they might behave out of line with their egalitarian ideals (should-would discrepancies). However, nearly two-thirds of these participants did not attribute their IAT performance to race-related attitudes, suggesting that awareness of implicit attitudes is confined to a small proportion of people, if interpretation of IAT performance is considered a measure of awareness.

Altogether, this prior research suggests that people might be able to perceive their implicit attitudes in the form of intuitions or gut reactions (i.e., people who think that such reactions are valid bases for making judgments [chronically or as instructed by a researcher] report explicit attitudes that are closer to their implicit attitudes). Additionally, research is suggestive that people might be able to observe and possibly draw attitudinal inferences from their behavior (e.g., test performance). However, the evidence is slim and appears to suggest low levels of awareness, only under certain circumstances and possibly only for some people. Additionally, the studies to date have relied on measures of explicit attitudes to indicate awareness, which confounds awareness with the propositional validation process believed to underlie these explicit attitudes (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, 2006). A question left open by prior research is whether people could be aware of their implicit reactions, even if they reject such reactions as a valid basis for an explicit attitude.

In line with this theorizing, we took a different approach to the question of awareness: We directly asked participants to predict their results on implicit attitude tests. In line with previous research we believed that participants would be able to perceive their spontaneous or implicit reactions even though only some might consider these reactions a valid basis for an explicit attitude. Accordingly, we believed that participants’ predictions of their implicit attitude results would be fairly accurate, even when they report different explicit attitudes.

The Present Research

Our research introduces a paradigm in which participants were asked to predict their own results on upcoming measures of implicit attitudes toward five different social groups. After participants completed the tests, we examined the degree to which their prior predictions corresponded with their actual test results. We used the IAT in our studies for the simple reason that it is the most widely used measure of implicit attitudes in the basic science literature, and its popularity has spread to more applied fields, including education, employment, business, politics, medicine and health (Greenwald et al., 2009; Nosek, Hawkins, & Frazier, 2011, 2012).2 The depth and breadth of the work that has relied on the IAT makes it particularly important to understand the extent to which people are aware of implicit attitudes as measured by this test.

We asked participants to predict and complete five different IATs for two reasons. First, we wanted to have a range of valenced target objects vis-à-vis the same comparison group – in these studies White adults. For instance, we included IATs that captured traditional implicit prejudice (e.g., White versus Black targets) and IATs in which the comparison group would likely be viewed less favorably than the other group (e.g., White children versus White adult targets).

The second reason for our use of five different IATs was based on theoretical considerations about the appropriate unit of analysis in considering the extent to which people are aware of their implicit attitudes. One way to examine awareness would be to assess the degree to which participants can make accurate prediction relative to other participants. This would involve correlating predictions and IAT scores across participants (between-subjects), one attitude target at a time. Another strategy would be to examine whether participants can make accurate predictions for one attitude object compared to other attitude objects. This latter method would look at the correlations between predictions and implicit attitude scores within-subjects (i.e., for each participant), across the five attitude targets. We believe that this second method of examining the accuracy of implicit attitude predictions is theoretically preferable.

To make accurate predictions of their implicit attitude results relative to the results of others (i.e., a between-subject analyses), participants need to have access not only to their own responses but also to knowledge of where their own responses line up relative to others’ responses. Although this latter question is interesting, it is altogether a different question. We were interested in whether participants could predict their own implicit attitude results, rather than their correctness in estimating how their attitudes compare to the attitudes of others. For these reasons, we examined the accuracy of participants’ implicit attitude predictions by correlating them with actual IAT scores within-subjects, across the five IAT’s that each participant completed. We then aggregated these correlations in a multi-level analysis to determine the accuracy of participants’ predictions on average. We return to the question of how one’s implicit attitude predictions compare to other people’s predictions towards the end of this paper, in a separate analysis across studies.

Study 1

In addition to the general question of whether people would be able to accurately predict their implicit attitude results, we pursued another question in Studies 1 and 2. Specifically, one of the explanations given for discrepancies between implicit and explicit attitudes is that people distort their explicit reports when being honest would reflect poorly on their desired self concepts (e.g., negative attitudes toward minority groups in the face of egalitarian social norms; Gawronski et al., 2006; Nosek, 2005, 2007; Wilson et al., 2000). To examine this possibility, half of the participants in Study 1 were informed that implicit attitudes are really cultural associations that may or may not reflect their true selves (removing self-concept threat), whereas the other participants were told that implicit attitudes are their true attitudes. If accuracy in predictions of one’s implicit attitudes are vulnerable to self-enhancing repression (Gawronski et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2000), then participants ought to make worse predictions in the “true attitudes” condition than in the less threatening “cultural associations” condition (Uhlmann & Nosek, 2012; Uhlmann, Poehlman, & Nosek, 2012).

Method

Participants and Design

Our aim in this and all the following studies was to collect at least 30–50 participants per between-subject (level-2) condition depending on availability of participants in the psychology subject pool of the University of Colorado Boulder at the time the studies were run. No data were analyzed until the full samples reported here were collected.

Sixty-nine undergraduate students participated in Study 1 for partial course credit. One participant did not complete the measures and three more participants made too-fast responses (< 300 ms) on more than 10% of their IAT trials and were thus excluded in accordance with criteria outlined by Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003). For the remaining 65 participants, 54% were women, and 82% self-identified as White. The other ethnic/racial identities were, “other” or multi-racial (5), Latino (3), Asian (2), Black (1), and Middle-Eastern (1). Ages ranged from 18–25, with a median age of 19.

This study used a multi-level design. The continuous relationship between the five IAT score predictions and the five IAT scores were modeled at level 1 for each participant. The outcome of this relationship was modeled across participants at level 2. At level 2 we additionally assessed the influence of the two differing IAT explanations on the strength of this relationship.

Materials

The IATs

Participants completed five evaluative (good vs. bad) IATs in an order that was individually randomized for each participant. Each IAT compared a different social group with the same comparison group (non-celebrity (unfamiliar) White young adults). The comparisons were labeled as, Black vs. White, Latino vs. White, Asian vs. White, Celebrity vs. Regular Person, and Child vs. Adult. All pictures representing children and celebrities also looked White to ensure the target social dimension was perceived as intended.

Ten faces (five male and five female) representing each social group were selected from the productive ageing lab database (Minear & Park, 2004) and from photos found publicly available online. Each face had a neutral expression, included the person’s hair and neck, and was shown against a grey background. The pictures used in each IAT were pretested and matched on likeability, except for those in the categories “child” and “celebrity” which were not expected to be comparable in liking to average White adults. The faces used to represent the comparison group (non-celebrity White young adults) were different in each IAT, thus there was a total of 50 non-celebrity White young adult faces used.

Each of the five IATs consisted of the following four blocks: (1) 20 trials sorting pictures of the two social groups, (2) 40 trials in which one group was sorted with positive words and the other group was sorted with negative words, (3) 40 trials in which the two social groups were reversed in position from Block 1, and (4) 40 trials in which the groups were paired with the opposite valence from Block 2.3 To ensure comparability between participants, all participants received compatible blocks first and incompatible blocks second (i.e., the order was not counterbalanced in line with considerations outlined by Egloff & Schmukle, 2002; Gawronski, 2002; Hofmann, Gschwendner, Wiers, Friese, & Schmitt, 2008)4. For all of the IATs, the compatible blocks were defined as those in which the comparison group is paired with good words, i.e., White + good for the three ethnic/racial IAT, Adult + good for the Child-Adult IAT, and Regular Person + good for the Celebrity-Regular Person IAT.

An IAT D-score following recommendations by Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji (2003) was calculated for each person on each IAT (i.e., the difference between the incompatible and the compatible blocks divided by their pooled standard deviation for each IAT for each participant). Higher scores on this measure reflect more negative implicit attitudes toward each target social group (i.e., Blacks, Latinos, Asians, children, or celebrities) relative to the comparison group.

IAT Explanation Manipulation and Training

Participants went through a thorough training procedure, during which they both learned about the meaning of implicit as opposed to explicit attitudes, and experienced completing IATs (on targets other than human social groups). Several steps were taken to manipulate beliefs that the IAT reveals either true attitudes or cultural associations. In the true attitudes condition, participants were first given a half-page introduction in which the IAT was described as revealing a person’s “true underlying attitude” that can sometimes differ from what people “think of themselves.” Participants were next given more specific information about the IAT sorting procedures and how implicit attitudes are inferred from those procedures. After each of these explanations, participants were asked to write down what they had just learned, using their own words. All references to IAT results in this section were consistently labeled as “true implicit attitudes.”

Conversely, participants in the cultural associations condition received a description of the IAT as revealing “culturally learned associations” that can differ from “what the person truly believes,” and all references to IAT results were phrased as “culturally-learned associations.” These participants were also asked to write down what they had learned about implicit associations and the IAT, following the description.

After learning that the IAT reveals “true implicit attitudes” or “cultural associations,” all of the participants were given first-hand knowledge of the IAT by completing two practice tests; one comparing Insects vs. Flowers and the second comparing Dogs vs. Cats. The practice IATs had only half the number of trials of the regular IATs to give participants a good sense of the test but not fatigue them unnecessarily. For both of the practice tests the participants were asked to first predict their score, complete the IAT, and indicate again how they thought they had scored. They then received automatized feedback on their actual IAT score.

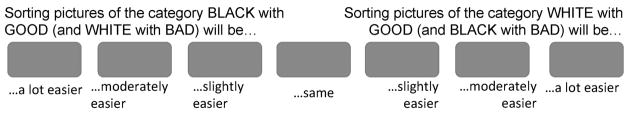

IAT prediction task

Prediction of one’s performance on an IAT was asked in terms of the perceived “ease” of completing the compatible versus the incompatible sorting tasks. For example, in predicting their performance on the Black-White IAT, participants were shown the faces that would appear in this test with one group appearing above the left side of a 7-point response scale and the other group appearing above the right side of the scale. Participants were encouraged to look at the pictures, “carefully listen to their gut feeling,” and then try to answer the question of which sorting task (e.g., sorting Black with good or sorting White with good) would be easier for them, and how much easier it would be (see Figure 1). This bi-polar scale thus made the comparative nature of the IAT clear and asked the participants to respond accordingly.

Figure 1.

Prediction scale participants used to make their predictions of their IAT score (example of Black-White IAT) in Study 1. Photos used in the actual IATs were depicted above the ends of the scales on the left and right. In Study 2, labels below the buttons were changed (see text).

For the feedback participants received on the practice IATs, the computed D-scores were translated into terms that were similar to the prediction scale: D-scores >.65 produced the feedback that a particular sorting combination had been “A LOT easier” than the other combination, D-scores between .65 to .35 were translated as “MODERATELY easier,” D-scores between .35 and .15 were translated as “SLIGHTLY easier,” and D-scores between .15 and −.15 produced the statement that the two sorting tasks were “the SAME” for the participant. These cut-offs were made according to conventions used on the IAT webpage (www.projectimplicit.com, Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2006, Personal communication from N. Sriram to I. Blair on July 6, 2009). Participants only received this feedback for the two IATs that were part of the training procedure, but never for the social group IATs.

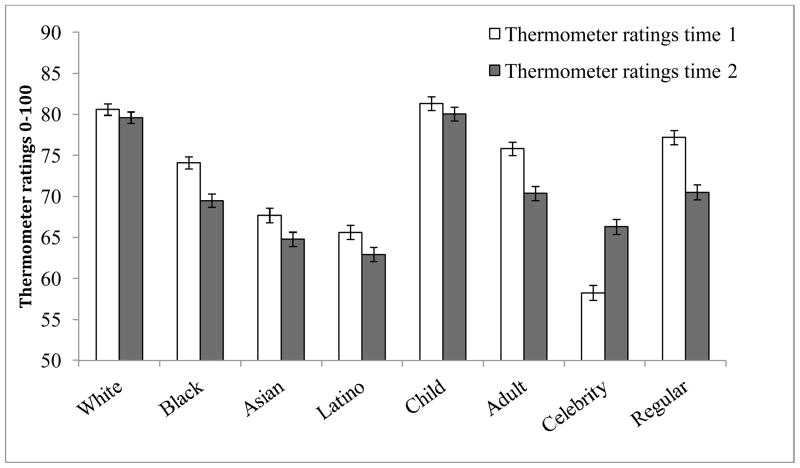

Explicit Ratings

Participants were asked to indicate their explicit group attitudes using a standard thermometer scale. For each group label, a scale appeared on the computer screen in the shape of a thermometer that ranged from “0 – very coolly” to “100 – very warmly.” Participants were asked to indicate how warmly or coolly they felt toward “Whites/Caucasians,” “Blacks/African Americans,” “Asians/Asian Americans,” “Latinos/Hispanic Americans,” “children,” and “celebrities.”

Manipulation Check

To assess the extent to which participants in each condition had in fact accepted the explanation they were given about the IAT, they were presented with four statements in a randomized order, each accompanied by a seven-point scale ranging from “1 – strongly disagree” to “7 – strongly agree.” The statements were, “The IAT measures my true underlying attitude”, “My IAT results have nothing to do with how I really feel about different groups of people” (reverse-scored), “The IAT measures a culturally learned association that I hold,” and “The IAT cannot say how I’m influenced by my culture” (reverse-scored). The first two and last two items were averaged, respectively (Cronbach’s α attitudes scale = .62, Cronbach’s α associations scale = .47), with higher scores indicating more agreement with the respective explanation.

Procedure

After informed consent was obtained, participants were seated in individual cubicles and completed the tasks in the following order: (1) explicit thermometer ratings, (2) explanation of the IAT (true attitudes vs. cultural associations, randomly assigned), (3) two practice IATs, each with a prediction, a “post-diction”, and computer feedback about the actual result, (4) predictions of IAT scores for all five of the critical IATs in one pre-determined order (Black-White, Asian-White, Latino-White, children-adults, celebrities-regular people), and (5) completion of the five IATs in random order. The experiment concluded with participants repeating explicit thermometer ratings on all of the groups.5 They then answered the manipulation check and demographic questions.

Results

Manipulation check

Before the primary analyses, we examined the manipulation check responses to determine whether participants had accepted the IAT explanation they were assigned. We ran a 2 (condition: true implicit attitudes vs. cultural association condition) by 2 (scale: IAT measures culturally-learned associations vs. IAT measures true implicit attitudes) mixed-model ANOVA with repeated measures on the second factor. The expected interaction of the two factors emerged, F(1, 63) = 31.08, p <.001, ηp2=.33. Participants in the true-attitudes condition agreed more with the idea that the IAT measured their true underlying attitudes (M=5.08, SE=.21), than their culturally learned associations (M=4.40, SE=.19), F(1, 63) = 10.80, p=.002, ηp2=.15. Contrarily, participants in the cultural associations condition agreed more with the idea that the IAT measured culturally learned associations (M=5.06, SE=.18) than their true underlying attitudes (M=4.15, SE=.20), F(1, 63) = 21.45, p<.001, ηp2=.25. Hence, participants believed that the IAT measured what we told them it measured – either their true underlying attitudes, or culturally learned associations that they hold.

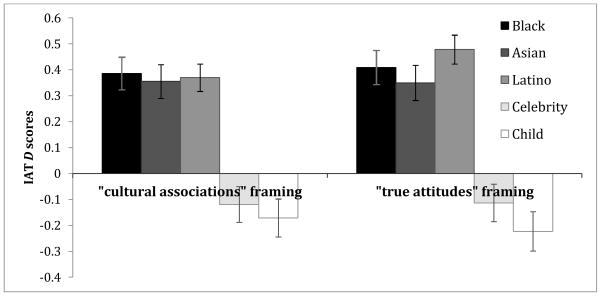

IAT scores

Figure 2 depicts the mean IAT D-scores. As expected, on average participants tended to have more positive implicit attitudes towards Whites as compared to Blacks, Latinos, or Asians, all three t(63)’s > 7.4, all p’s < .001, all ηp2’s>.47, but more positive attitudes towards celebrities as opposed to regular people, t(63) = −2.32, p = .02, ηp2=.08, and more positive attitudes towards children as opposed to adults, t(63) = −3.74, p <.001, ηp2=.18. There were no effects of explanation condition on any of these scores, t(63)’s < 1.5, all p’s > .16.

Figure 2.

Study 1: Mean IAT scores by condition. Higher scores mean more positive implicit attitudes towards the comparison group (i.e., regular White adult). Negative scores indicated more positive scores towards the target group (Black, Asian, Latino, celebrity, or child). Error bars are calculated from mean square errors from a 5 (target) x 2 (condition) ANOVA on IAT scores.

Accuracy of predictions

In order to examine whether participants could accurately predict the patter of their five IAT results, we estimated a multilevel model6 in which each participant’s five IAT scores were modeled as a function of that person’s five IAT predictions at the first level. Because we wanted the sizes of the resulting random slopes to be indicative of participants’ accuracy in predicting the patterns of their results, we individually standardized IAT scores and predictions for each participant.7 Thus, the slopes from this analysis are akin to a correlation coefficient for each participant that estimates the degree to which his or her IAT scores are associated with his or her predictions. At level two, we looked at the average size of these random slopes (the fixed effect), and also modeled them as a function of the explanation manipulation (between-subjects). The results from this analysis are given in the left column of Table 1.8 The top part of Table 1 gives the tests of the fixed effects and the bottom shows the variances of the random error components of the model.

Table 1.

Study 1: IAT D-scores regressed on IAT score predictions (left) and explicit thermometer ratings (right)

| Parameters (DV: IAT D-scores) | Prediction model estimates | Imp.-exp. model estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| IAT score predictions | .53*** | |

| Predictions × condition | .09† | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | .01 | |

|

| ||

| Random effect variances | ||

| IAT score predictions | .041 | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | .077 | |

| Residuals | .550*** | .741*** |

|

| ||

| Goodness of fit | ||

| −2 log likelihood | 750.43 | 850.39 |

p < .11

p<.001

All level-1 variables are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. Accordingly the intercept in this model would be 0 and is not included in the model. Similarly, the main effect of condition on these centered IAT scores is not included either. “Condition” represents a level-2 condition assignment. It is coded “−1” for the “cultural associations” condition, and “1” for the “true attitudes” condition.

As Table 1 shows, participants’ predictions of their IAT results corresponded significantly with their actual IAT scores, b= .53, t(61) =9.80, p <.001. As previously discussed, the slope from this standardized model can be interpreted as the average within-subject correlation between predictions and actual IAT scores. Looking at the distribution of these individual correlations revealed that it was negatively skewed, making the median within-participant correlation between predictions and IAT scores higher than the average, r = .62. The random components of this model (see lower half of Table 1) furthermore indicated that random variation in these slopes across participants was not significant.

As Table 1 also indicates, the manipulation of IAT explanation only minimally affected participants’ prediction accuracy (predictions by condition interaction). Contrary to a threat hypothesis, participants’ predictions were actually non-significantly more accurate in the “true-attitudes” condition than in the “associations” condition, b= .09, t(60) =1.64, p =.11.

The lack of a condition effect made us wonder whether or not the manipulation possibly only affected the more socially sensitive racial/ethnic IATs. Additionally, we were interested in whether participants’ accuracy stemmed mainly from predicting the difference between the minority IATs (which indicated a pro-White bias), and the other two IATs (which indicated biases against the White comparison group, see Figure 2). Results of an analysis looking only at predictions of ethnic/racial IATs did not support either of these speculations. First, there was still evidence that participants could predict their pattern of results for only these three (mostly pro-White) IATs, even in this underpowered analysis of only three data points per participant, b=.32, t(38.0) = 2.80, p=.008. Additionally, there was still no evidence that thinking about the IAT as revealing “true attitudes” made participants less accurate in their predictions of these results. As before, the direction of the (non-significant) slope indicated more accuracy in the “true attitudes” as opposed to the “cultural associations” condition, b=.15, t(38) = 1.29, p=.21.

Relations with explicit attitudes

We conducted an additional analysis to determine the relation between participants’ explicit thermometer ratings and their IAT scores. This time we modeled level-1 IAT scores as a function of participants’ explicit attitudes (their thermometer ratings) measured prior to the IATs.9 The results of this analysis are reported in the right column of Table 1. They show that participants’ explicit thermometer ratings were unrelated to their IAT scores across the five IATs, b = .01, t(64) =.10, p =.92.

Discussion

The purpose of Study 1 was to investigate people’s ability to predict their IAT results. With regard to five social-group comparisons, we found that participants predicted their results with a fair amount of accuracy. Participants were furthermore as accurate (even a little more so) in their predictions when they were led to believe that the IAT revealed their true attitudes, as they were when they were led to believe that the IAT revealed culturally learned associations. At the same time, results from the manipulation check showed that participants accepted the explanations they were given. Taken together, the pattern of results suggests that people can predict their performance on implicit attitude tests even as they face the possibly unpleasant revelation that these “true attitudes” differ from their explicit attitudes.

Indeed, participants in this study reported explicit attitudes that were distinct from their IAT results, even as they demonstrated that they could accurately predict the latter. This last point supports the argument that lack of correspondence between implicit and explicit measures of attitudes says little about how aware people are of their implicit reactions. Studies concerned with the correspondence between implicit and explicit measures of attitudes provide only circumstantial evidence on this issue (Gschwendner et al., 2006; Hofmann et al., 2005a, 2005b; Smith & Nosek, 2011; Ranganath et al., 2008).

There are additional questions that remain to be answered. Specifically, the prediction task in Study 1 asked participants to make an operational prediction (i.e., “Which of two blocks in this task will be easier to complete?” See Figure 1). Participants might have some sort of procedural awareness about their response impulses, but not about their spontaneous attitudinal reactions towards the groups. Since it is the latter construct (attitudes) that we intended to address, Study 2 was conducted to replicate the results with a more conceptual prediction measure of participants’ implicit attitudes towards the groups.

Study 2

Method

Participants and Design

Seasonal availability allowed us to sample more participants in Study 2 to further investigate the weak condition effects found in Study 1. Data were only analyzed after the full sample reported here was collected. Ninety-three undergraduate students participated in the study for partial course credit. Three participants were excluded from data analysis: One participant made too-fast responses (<300 ms) on 19% of the IAT trials (Greenwald et al., 2003), and two participants were missing too much data to be included. The remaining 90 participants were 64% women, and 81% identified as White. The other ethnicities were: 5 “other” or mixed-races, 5 Arab/Middle-Eastern, 4 Asian, 2 Latino and 1 Black. Age range was 18–25 years, with a median age of 19.

Study 2 used the same design as Study 1. That is, the continuous relationship between predictions of IAT results and actual IAT scores was calculated for each participant at level 1, and the effect of the IAT explanation condition on this relationship was assessed across participants at level 2.

Materials and procedure

The materials and the procedure were exactly the same as those used in Study 1 with two exceptions. First and most significantly, we modified the measure that the participants used to predict their IAT results. As before, participants saw the pictures they would be sorting in the IATs accompanied by instructions encouraging them to look at the pictures and listen to their gut reactions. However, instead of focusing on which of two IAT blocks would be easier to complete, the prediction measure asked participants directly about their “true implicit attitudes” or their “culturally learned associations”, depending on IAT-explanation condition. Thus, the final prediction scale read, e.g., “I predict that the IAT comparing my reactions to BLACK vs. WHITE will show that my true implicit attitude [culturally learned association] is…” (1) “a lot more positive towards BLACK”, (2) “moderately more positive towards BLACK”, (3) “slightly more positive towards BLACK”, (4) “same”, and then the opposite labels on the second half of the scale (e.g., “slightly more positive towards WHITE,” etc.). Except for these changes in the labels, the prediction scale still looked similar to the one depicted in Figure 1.

The second modification was made to reinforce the IAT explanation condition manipulation, given its weak effect in Study 1. Following score feedback on the two practice IATs (Insect-Flower and Dog-Cat), participants were asked to reflect what their results said about their “true attitudes” (or their “culturally learned associations,”) in an additional writing task. As in Study 1, the effectiveness of the manipulations was assessed by four manipulation check questions in the end of the study (Cronbach’s α attitudes scale = .68, Cronbach’s α associations scale = .48).

Results

Manipulation check

The manipulation check scales were analyzed as a function of IAT explanation condition. The expected interaction between scale and condition emerged again, F(1, 88) =11.14, p = .001, ηp2=.11. Participants in the true-attitudes condition agreed significantly more that the IAT measured their underlying true attitudes (M=4.54, SE=.21) than culturally learned associations (M=4.04, SE=.18), F(1, 88) =4.51, p =.036, ηp2=.05. Conversely, participants in the cultural associations condition agreed more that the IAT measured culturally learned associations (M=4.51, SE=.18) than true underlying attitudes (M=3.90, SE=.21), F(1, 88) =6.74, p =.011, ηp2=.07.

Accuracy of predictions

As in Study 1, a multi-level model was estimated in which each participant’s five IAT scores were modeled as a function of that person’s five IAT predictions (both individually standardized) at the first level, within-subjects, and then the random slopes from this level were modeled at level 2 as a function of the IAT explanation condition, between-subjects. The results are summarized in the left column of Table 2. We again found a significant relationship between the IAT predictions and actual scores, b = .55, t(86) =12.02, p <.001. The distribution of the correlation coefficients was again negatively skewed so that the median correlation was even higher, r = .72.

Table 2.

Study 2: IAT D-scores regressed on IAT score predictions and explicit thermometer ratings, simple relationships and simultaneous regressions.

| Parameters (DV: IAT D-scores) | Prediction model estimates | Imp.-exp. model estimates | Sim. regr. model estimates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| IAT score predictions | .55*** | .59*** | |

| Predictions × condition | −.00 | −.04 | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | −.20*** | .06 | |

| Therm. × condition | −.09 | ||

|

| |||

| Random effect variances | |||

| IAT score predictions | .048 | .040 | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | .028 | .079* | |

| Residuals | .533*** | .747*** | .475*** |

|

| |||

| Goodness of fit | |||

| −2 log likelihood | 1027.56 | 1161.51 | 1023.31 |

p<.05

p<.001

All level-1 variables and the dependent IAT scores are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. Condition is coded “−1” for the “cultural associations” condition, and “1” for the “true attitudes” condition.

An examination at level 2 of the model again showed no evidence that the explanation manipulation had any effect on the accuracy of participants’ predictions, b = .00, t(86) =−.09, p =.93. As in Study 1, we also looked at these relationships for only the three ethnic/racial IAT predictions. Prediction accuracy for these three IATs was comparable to what we found in Study 1, b=.33, t(45)=3.46, p=.001, and there was not a significant difference by explanation condition, b=.17, t(45) = 1.75, p=.09. As in Study 1, the direction of this slope was opposite to a threat hypothesis, showing a tendency for participants to be more accurate in predicting the pattern of their racial/ethnic minority IAT scores when they thought of them as revealing “true attitudes” than when they thought of them as revealing “culturally learned associations.”

Explicit attitude relations

The next multi-level model tested whether participants’ explicit thermometer ratings were related to their IAT scores (see the middle column of Table 2). This analysis showed a significant relationship, b = −.20, t(89) =−4.12, p < .001.10 This relationship was largely in line with previous research on implicit-explicit relationships (Blair, 2001; Hofmann et al., 2005a, 2005b), and as such weaker than the relationship between IAT score predictions and IAT scores (b=.55 opposed to .20, see Table 2). Additionally, the relationship between thermometer ratings and IAT scores disappeared once participants’ IAT predictions were added to the model as a covariate, b = .06, t(104.27) =1.09, p =.27 (see rightmost column in Table 2).

Discussion

Study 2 replicated the results of Study 1 with a more conceptual prediction task. Instead of predicting which of two blocks would be easier to complete in an IAT, Study 2 asked participants to predict their implicit attitudes in terms of positivity for one group over another. Participants were just as accurate at making this prediction as they were in Study 1. The relationship between implicit and explicit attitude measures again followed a different pattern. Although statistically significant in this study, this relationship was a) substantially weaker than the relationship between implicit attitudes and their predictions, and b) could be entirely explained through participants’ predictions of their implicit attitudes. We believe this to be consistent with the APE model: Participants are generally able to notice their implicit reactions, but differ in how much validity they grant such reactions and the extent to which other propositions carry more weight in explicit attitude responses, resulting in an average implicit-explicit relationship that is low, as found in previous research (Blair, 2001; Hofmann et al., 2005a, 2005b).

Results so far are consistent with the hypothesis that participants can accurately predict their IAT results. However, looking at the groups that participants were asked to evaluate, another possible explanation is that participants simply predicted the attitudes that “make the most sense” for people in the cultural context. That is, most contemporary Americans would probably predict that the average American would have somewhat more negative associations with ethnic minorities as opposed to Whites, but somewhat more positive associations with children as opposed to adults, and with celebrities as opposed to regular people. The presumed accuracy in their predictions could thus be interpreted as showing that people have good naïve theories about social norms rather than showing unique insight into their own implicit attitudes (F. Strack, personal communication, July 2011).

We addressed this alternative explanation in two ways. First, as reported earlier for both Studies 1 and 2, we examined participants’ predictions for only the three minority IATs. As shown in Figure 2, average biases were similar across these three minority groups, which would suggest that “good guesses” (no variance across groups) would show no relation with actual scores. This was not what we found, suggesting that participants showed insight into their own unique responses.

Second, we decided to investigate whether participants’ predictions would uniquely describe their own response pattern, compared to the predictions made by another person. Using the data from Study 211, we randomly paired participants within a condition, one labeled “A” and the other “B”, and then examined the accuracy (variance accounted for in IAT scores) of each participant’s predictions compared to the predictions of the random other participant. Table 3 shows the results when participant A’s IAT scores are regressed onto both participant A’s and participant B’s predictions (left columns), and when participant B’s IAT scores are regressed onto both A’s and B’s predictions (right columns). There was a significant zero-order relationship between IAT scores and the other person’s predictions: A on B: b = .36, t(86) =7.57, p <.001, B on A: b = .34, t(86) =6.53, p <.001. However this relationship was substantially lower than the relationship between participants’ predictions and their own IAT scores (b = .55, t(86) =12.02, p <.001), as confirmed by two paired-sample t-tests, participant A’s IAT score: t(89)=3.18, p = .002, ηp2=.10, participant B’s IAT score: t(89) = 3.49, p=.001, ηp2=.12. Furthermore, the relationships between IAT scores and the other person’s predictions dropped even further when own predictions were included in the models, A on B: b = .18, t(93.87) =3.68, p <.001, B on A: b = .17, t(95.97) =3.61, p <.001. Participants’ own predictions for themselves furthermore continued to predict a comparable amount of variance, even with the predictions of the random other participants in the model, participant A’s own prediction accuracy: b=.50, t(96.60) =10.25, p<.001, participant B’s own prediction accuracy: b=.48, t(94.96) =9.70, p<.001.12

Table 3.

Study 2: Random paring of predictions and IAT D-scores between two participants (A and B).

| Parameters | DV: Participant A’s IAT D-score | DV: Participant B’s IAT D-score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple model estimates | Sim. reg. model estimates | Simple model estimates | Sim.rReg. model estimates | |

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Participant A’s IAT score pre-dictions | .50*** | .34*** | .17*** | |

| Participant B’s IAT score pre-dictions | .36*** | .18*** | .48*** | |

| A’s predictions × Condition | −.00 | −.08 | −.02 | |

| B’s predictions × condition | −.01 | .07 | .02 | |

|

| ||||

| Random effect variances | ||||

| Participant A’s IAT score pre-dictions | .057 | .080* | .043 | |

| Participant B’s IAT score pre-dictions | .026 | .054 | .055 | |

| Residuals | .683*** | .466*** | .646*** | .481*** |

|

| ||||

| Goodness of fit | ||||

| −2 log likelihood | 1124.55 | 1010.99 | 1121.67 | 1018.27 |

p<.05

p<.001

All level-1 variables, including the dependent IAT scores, are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. Pairing of participants A and B are entirely random, but fixed within condition. Different random pairings would lead to slightly different results.

In sum then, there did seem to be a normative pattern of IAT responses, and thus participants’ predictions explained variance in the pattern of their co-participants’ IAT scores. Nevertheless, participants’ predictions for their own scores explained variance over and above this general pattern. That is, deviations of participants’ individual IAT patterns from the general pattern could be largely explained by participants’ own unique predictions for their scores. Study 3 was conducted to address this issue more directly.

Study 3

Study 3 had two aims. One was to further investigate the difference between unique insight and predictions based on normative assumptions. In addition to predicting their own IAT results, participants were asked to predict how they thought a “typical or average CU student” in this study would respond. If participants have unique access into their own implicit responses, then self predictions should explain variance in IAT scores over and above predictions made for the average student. This is a particularly conservative test of unique insight, because participants are likely to egocentrically base their predictions for the average student on their own intuitions (Krueger, 1998; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977).

The second aim of Study 3 was to remedy methodological ambiguities in Studies 1 and 2. First, we provided participants with a continuous sliding scale for the prediction of their IAT results, rather than the 7-point scale used previously. Second, we added ratings of “adults” and “regular people” to the explicit thermometer measures. These allowed us to compute difference scores for children as opposed to adults and celebrities as opposed to regular people more analogous to the comparative scores obtained from the IATs (rather than contrasting all scores simply from the normative comparison category “White”). The purpose of both of these changes was simply to get more accurate results and rule out the possibility that certain results (e.g., low implicit-explicit correlations) were methodological artifacts; we did not expect any meaningful differences in the pattern of results.

Method

Participants and Design

One hundred and twenty undergraduate students completed the study for course credit.13 One participant failed to understand the IAT instructions and did not complete the study. Of the final 119 participants, 77 (65%) were women, and 84% identified as White, with the remaining 19 participants identifying as Black (5), Latino (4), Asian (6), or mixed-ethnicities (4). Ages ranged from 18–32 years, with a median age of 18.

The study again consisted of a multi-level design. On level 1 we estimated a regression for each participant to analyze the continuous unique relationships between actual IAT scores as the criterion and, simultaneously, both IAT score predictions for self and IAT score predictions for the average student as predictors. On level 2, across participants, we estimated these relationships as a function of prediction order (self first vs. other first, between-subjects).

Materials

Materials were almost identical to the materials used in Study 2, with the exception of the following changes.

Predictions for the average participant

A second prediction task was added to this study. Specifically, participants were encouraged to imagine “a typical or average student” from their university participating in this study and to predict how this student would respond to the same questions the participants were answering for themselves. The participants were further told that their predictions for another student would be tested for accuracy. To reinforce this perspective-taking task participants were asked to provide predictions for the average student on all explicit thermometer ratings as well as IAT scores.

IAT training

The IAT training procedure was similar to that used in the “true implicit attitudes” condition of Study 2, except that all instances of the word “true” were omitted, and participants were simply asked to predict their “implicit attitudes” (instead of their “true implicit attitudes”). In line with this change, implicit attitudes were described as “the underlying attitude that gets triggered spontaneously and that might not be consciously known,” and explicit attitudes were now described as “what you like once you’ve had time to think and reflect about it.”

IAT score prediction

The IAT prediction task was similar to the one used in Study 2 in the true-attitudes condition, except the word “true” was omitted, and participants saw a sliding scale instead of seven buttons. This scale had seven equidistant cut-off lines placed along its length that were labeled the same as the buttons in Study 2 (e.g., “6 - moderately more positive towards WHITE”). The computer registered .1-increments between a choice of 1.0 and a choice of 7.0 (both anchors indicating “a lot more positive towards group X”). Participants thus had 61 options to use to predict their own, and the average student’s, attitudes. Participants either predicted all of their own attitudes first in one block and then all attitudes for the average participant, or vice versa. In contrast to Studies 1 and 2, the order of the target attitudes that participants predicted were individually randomized for each participant within each block (i.e., one random order for IAT self predictions, and another random order for IAT other predictions).

IAT training feedback

Participants received more precise feedback on their flower-insect and dog-cat training IATs (as before, they did not receive feedback on the social-group IATs). Their D-scores (Greenwald et al., 2003) were converted into a numerical value between 1 and 7, which they saw in addition to the sentence describing their bias. Thus, a participant could see a sentence, such as, for instance, “your IAT score indicates that you have moderately more positive attitudes towards CAT as opposed to DOG. On the 7-point scale you used, this corresponds to a value of 5.2”).14

Additional explicit thermometer ratings

Participants were asked to rate eight groups on the thermometer scale (0–100), once to indicate their own feelings and once to estimate the feelings of an average participant. In addition to the groups rated in the previous two studies (Whites/Caucasians, Blacks/African Americans, Asians/Asian Americans, Latinos/Hispanic Americans, children, and celebrities), participants also rated “adults” and “regular people (non-celebrities)” in a constraint-randomized order to avoid confusion. That is, participants rated the groups in three blocks that appeared in random order for each participant (1. ethnic groups, in a different random order for each participant 2. adults then children, and 3. celebrities then regular people).

Procedure

All participants began the experiment with an announcement that this experiment was concerned with their ability to predict their own scores on a computerized test, as well as to predict the response of the average student from their university participating in this study. They were encouraged to imagine such an average student, but not to think of a specific person they knew. Participants were then randomly assigned to a “self-first” or “other-first” condition in completing both the explicit attitudes measures and the IAT predictions. The order of events was, (1) explicit thermometer ratings for self and other, with either self first or other first, (2) the IAT training procedure described above, (3) predictions of self and other scores on the five social-group IATs, in the same order as the thermometer ratings (self first or other first), (4) completion of the IATs, and (5) another round of explicit thermometer ratings, this time only for self.15 The experiment concluded with a demographic questionnaire.

Results

Accuracy

We ran the same multi-level analysis conducted in Studies 1 and 2 on the data of Study 3, modeling the relationship between IAT scores and IAT predictions on level 1, and tested for order effects on level 2. Results are depicted in the left column of Table 4. Participants again predicted their IAT results with considerable accuracy, b = .59, t(117) =16.26, p <.001. The median correlation per participant of this skewed distribution was r = .72. The order in which participants completed the measures (self-first vs. other-first) did not influence accuracy, t <1.6, n.s..

Table 4.

Study 3: IAT D-scores regressed onto a participant’s prediction for their own score (left), the same participant’s prediction for the average participant and their own score simultaneously (2nd column), IAT scores regressed onto explicit thermometer ratings (3rd column), and both self-predictions and explicit ratings simultaneously (right).

| Parameters (DV: IAT D-scores) | Prediction model estimates | Self-vs-aver. model estimates | Imp.-exp. model estimates | Sim. reg. model estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||

| IAT score predictions self | .59*** | .34*** | .58*** | |

| self predictions × order | −.02 | −.04 | .07 | |

| IAT score predictions other | .34*** | |||

| other predictions × order | −.00 | |||

| Explicit therm. ratings | .27*** | .03 | ||

| Exp. Therm. rating × order | .07 | .07 | ||

|

| ||||

| Random effect variances | ||||

| IAT score predictions self | .028 | .009 | .019 | |

| IAT score predictions other | .033 | |||

| Explicit therm. ratings | .111** | .077** | ||

| Residuals | .505*** | .452*** | .655*** | .451*** |

|

| ||||

| Goodness of fit | ||||

| −2 log likelihood | 1313.49 | 1268.38 | 1501.44 | 1306.61 |

p<.01

p<.001

All level-1 variables are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. “Order” represents a level-2 (between-subjects) condition assignment, one half predicted their own scores first (assigned code −1), another half predicted the score of the average participant first (coded 1).

Predictions for the average participant

Mean pattern

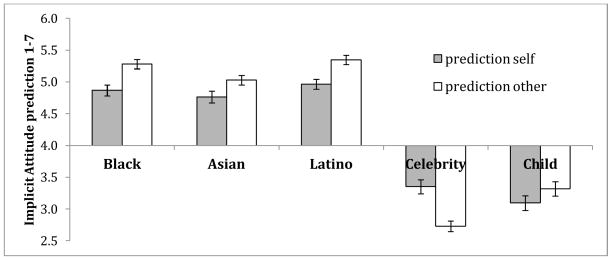

As expected, participants predicted very similar patterns of responses for the average participant as they predicted for themselves. The mean within-subject correlation was r= .73 (see Figure 3). The distribution of these correlations was highly skewed and showed a median of r=.86.16 To examine mean differences in self versus other predictions, we conducted a 2(prediction for self vs. prediction for other) by 5(social groups) by 2(order) mixed-model analysis with repeated measures on the first two factors. The principal effect of interest was an interaction of self vs. other by groups, F(4, 468)=28.63, p<.001, ηp2=.20. Simple effect contrasts showed that participants predicted that the average participant would show more bias than they themselves would show in favor of Whites as opposed to Blacks, F(1, 117)=25.25, p<.001, ηp2=.18, Asians, F(1, 117)=10.05, p=.002, ηp2=.08, and Latinos, F(1, 117)=24.96, p<.001, ηp2=.18; and more bias than they would show in favor of celebrities over regular people, F(1, 117)=44.86, p<.001, ηp2=.28, but less bias than they would show in favor of children over adults, F(1, 117)=4.07, p=.046, ηp2=.03.

Figure 3.

Study 3: Mean predictions of participants’ own IAT score and predictions for IAT scores of the average participant participating in the same study. Scales range from 1–7 with scores above 4 indicating more bias in favor of the comparison group (White, regular, or adult), and score below 4 indicating bias in favor of the target group (Black, Asian, Latino, celebrity, or child). All pairwise differences between predictions for self and predictions for the average participant are significant (see text). Error bars are calculated from mean square errors from a 2 (self vs. other) x 5 (targets) x 2 (self first vs. other first) ANOVA.

Accuracy of IAT predictions for self vs. predictions for other

In order to see whether participants had insight into their own implicit responses over and above the pattern they predicted for the average participant, we regressed participants’ IAT scores simultaneously on their predictions for themselves and their predictions for the average participant on level 1 (within-subjects), and looked at how these relationships were moderated by task order on level 2 (between-subjects). Results are shown in the second column of Table 4. Participants’ predictions for the average participant were significantly related to their IAT scores, b = .34, t(266.18) = 6.70, p <.001. However, their predictions for themselves explained IAT variance over and above this relationship, b = .34, t(241.72) = 7.10, p <.001, suggesting unique insight into their own pattern of implicit responses. None of these relationships were moderated by task order, all |t|’s <= 1.

Explicit ratings

For better comparison to IAT scores, each explicit attitude reported for the self was computed as the difference between two thermometer ratings (White minus each of the three ethnic groups, adult minus child, and regular person minus celebrity), and these were used as predictors of IAT scores. Results are summarized in the two right-most columns of Table 4. Participants’ thermometer ratings were moderately correlated with their IAT scores, b = .27, t(118) = 5.61, p <.001. However, this relationship disappeared when participants’ IAT predictions (for self) were included in the model, b = .03, t(136.42) = .59, p =.56. The random components in this model indicated that these implicit-explicit relationships were highly variable across participants. The highly accurate implicit attitude predictions, on the other hand, showed non-significant random variance across participants, as in the previous studies.

Discussion

Study 3 showed that participants have unique insight into their own implicit responses, over and above normative assumptions. Specifically, the predictions participants made for themselves explained variance in actual IAT scores over and above the predictions they made for an average student participating in the same study. Despite making the explicit attitude scores more comparable to IAT scores, the relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes followed similar patterns as in the previous studies.

Study 4

The purpose of Study 4 was to examine the necessity of the IAT training procedure used in the previous 3 studies. That is, participants in our prior studies were given extensive explanation about the meaning of implicit attitudes and the IAT as a measure of such attitudes, including direct experience with two practice IATs. We were curious to see how much explanation and experience with implicit-attitude measurement was in fact necessary for participants to make accurate predictions. An exploration of this issue would also be informative about people’s general insight into the difference between their spontaneous reactions and deliberate attitudes.

To test this question, we manipulated both the amount of explanation and experience with the IAT in a 2 (minimal explanation vs. full explanation) by 2 (no experience vs. full experience) between-subjects factorial design.

Method

Participants

One hundred and fifty-seven participants completed this study in exchange for partial course credit. One participant was excluded for responding faster than 300 milliseconds on 55% of the IAT trials (Greenwald et al., 2003). Due to computer errors, demographic information was available for only 154 of the remaining 156 participants. Of those, 62% were female, and 77% self-identified as White. The remaining 23% self-identified as Black (2), Latino (7), Asian (16), Native American (1), Middle-Eastern/Arab (3) or as multi-ethnic (7). Ages ranged from 18–32 years, with a median age of 19.

Design

Using a multi-level design, the continuous relationship between participants’ IAT score predictions and their actual IAT scores were modeled for each participant separately at level 1. At level 2 we modeled this relationship as a function of a 2 (minimal explanation vs. full explanation) by 2 (no experience vs. full experience) between-subjects factorial design.

Materials and Procedure

The procedure and design of Study 4 are graphically depicted in Table 5. After completing explicit thermometer ratings, as in Study 3, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions.

Table 5.

Design and procedure Study 4.

| Procedure | Condition | Full explanation | Minimal explanation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full experience | No experience | Full experience | No experience | ||

| I) Explicit thermometer ratings | !! | ||||

| II) IAT training procedure | Step 1: Explanations and writing tasks: Implicit & explicit attitudes; IAT procedure. | !! | -- Instead: Filler writing task and prediction prompt |

||

| Step 2: IAT experience and feedback with insect-flower IAT & dog-cat IAT | !! | -- | !! | -- | |

| Step 3: Explanatory writing task: Reflect on your IAT results | !! On real results |

!! On hypothetical results |

-- | -- | |

| III) 5 social group IATs | Score predictions | !! With reference to “gut reactions” |

!! Without reference to “gut reactions” |

||

| Actual test completions | !! | ||||

| IV) Explicit thermometer ratings | !! | ||||

| V) Demographics | !! | ||||

As can be seen in Table 5, the IAT training procedure used in the previous studies can be organized into 3 steps: (1) two explanatory writing tasks on the meaning and measurement of implicit attitudes; (2) experience with predicting, completing, and receiving feedback on an insect-flower and a dog-cat IAT; and (3) reflecting on the meaning of the results of the two training IATs. Experience with the IAT (full vs. no) and explanation of the difference between implicit and explicit attitudes (full vs. minimal) was manipulated by systematically eliminating steps in this training procedure.

Specifically, as can be seen in Table 5, participants in the full-explanation/full-experience condition completed all steps as in the previous studies, using the materials from Study 3. Participants in the full-explanation/no-experience condition did not complete the two practice IATs (step 2). Accordingly, step 3 for these participants involved writing a hypothetical interpretation about what their results would mean if they were to complete an insect-flower and a dog-cat IAT.

Participants in the minimal-explanation/full-experience condition completed only step 2 of the training procedure, but did not complete steps 1 and 3. Instead of step 1, they completed a filler task that had the same title, “Do you know yourself?”, but asked participants to describe in detail what they had done on the previous afternoon. Participants in this condition then continued to step 2 and completed the insect-flower and dog-cat IATs and received feedback on their actual results. These participants’ predictions were thus informed by experience with the IAT, but not by theoretical reflection about its meaning.

Lastly, participants in the minimal-explanation/no-experience condition did not complete any of the three training steps. After completing the thermometer ratings, participants in this condition only completed the filler writing task.

After the training procedure (or no training), participants in all conditions predicted their IAT scores for the five social-group IATs in an order randomized for each participant, and then completed the actual IATs, also in individually randomized orders.

In order to explain the prediction task to participants in both minimal-explanation conditions, they were given the following prompt before making their predictions, modeled after the IAT webpage’s introductory portal (www.projectimplicit.com, Nosek et al., 2006):

“This study uses a method that examines some of the divergences that may occur between people’s implicit and their explicit attitudes. This new method is called the Implicit Association Test, or IAT for short. In a minute you will complete some IATs and we are interested in whether you can predict your performance on each one. Past research shows that people are actually pretty good at predicting their scores, even if they aren’t entirely sure. So even if the predictions seem difficult, just try your best to be as accurate as possible.”

The predictions themselves for the minimal-explanation conditions were also slightly modified in that they did not encourage participants to listen to their gut reactions. Instead, the screen where participants were asked to make their predictions showed the same pictures that would be used in the IATs and asked participants “if you took an IAT to measure your implicit attitude, what would it show?” The prediction scale itself (taken from Study 3) was the same for participants in all conditions. After completing the IATs, all participants repeated the explicit thermometer ratings, and were asked to provide demographic information.

Results

Effects of condition assignments on accuracy

Participants’ IAT scores, standardized for each participant, were regressed onto their within-subject standardized predictions, for each participant separately on level 1. The resulting slopes (reflecting accuracy of predictions) were modeled as a function of training condition on level 2. Specifically, we analyzed the effects of two binary contrast-coded between-subjects predictors on level 2, one for full explanation vs. minimal explanation (coded −1 and 1, respectively), and one for full experience vs. no experience (also coded −1 and 1, respectively), as well as their interaction (i.e., their product). Results are depicted in Table 6.

Table 6.

Study 4: IAT D-scores regressed onto IAT score predictions and explicit thermometer ratings.

| Parameters (DV: IAT D-scores) | Prediction model estimates | Imp.-exp. model estimates | Sim. Reg. model estimates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| IAT score predictions | .54*** | .55*** | |

| Predictions × Explanation | −.02 | −.02 | |

| Predictions × Experience | .00 | −.01 | |

| Predictions × Explanation × Experience | .03 | .01 | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | .24*** | −.02 | |

| Therm. × Explanation | −.03 | −.02 | |

| Therm. × Experience | .05 | .03 | |

| Therm. × Explanation × Experience | .04 | .04 | |

|

| |||

| Random effect variances | |||

| IAT score predictions | .000 | .000 | |

| Explicit therm. ratings | .087** | .058* | |

| Residuals | .574*** | .686*** | .530*** |

|

| |||

| Goodness of fit | |||

| −2 log likelihood | 1297.22 | 1997.58 | 1805.64 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

All level-1 variables are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. “Explanation”, “Experience”, and “Explanation × Experience” refer to Level-2 (between-subject) predictors that are contrast-coded “−1” for no or minimal, and “1” for full explanation or experience, respectively. The interaction term is the product of these two codes.

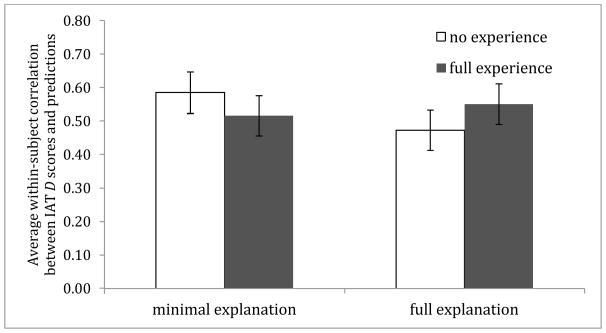

As in the previous studies, participants predicted their IAT results with considerable accuracy across conditions, b=.54, t(776.0) = 17.61, p < .001. The median within-participant correlation in this study was r=.66. Surprisingly, the systematic impoverishment of the training did not affect accuracy. Neither explanation, b=−.02, t(776) =−.64, n.s., nor experience, b =.00, t(776) =.08, n.s, nor their interaction, b =.00, t(776) =.08, n.s, had any effects on the accuracy of IAT predictions. The average within-subjects correlations per condition are graphed in Figure 4. As can be seen, results went in unexpected directions. Although none of these differences were significant, participants in the minimal-explanation/no-experience condition tended to be the most accurate in predicting their results.

Figure 4.

Study 4: Average within-participant correlation between IAT score predictions and actual IAT scores by condition. Error bars are calculated from mean square errors from a 2 (explanation) x 2 (experience) ANOVA on participants’ individual correlations calculated separately in a first step.

Relationship of IAT scores with explicit ratings

As in Study 3, the thermometer ratings based on group comparisons showed a significant, if moderate, within-participant relationship with IAT scores, b=.24, t(154.00) = 5.92, p < .001 (see middle and right column of Table 6). However, once controlling for participants’ IAT predictions, these relationships dropped to nil, b=−.02, t(206.60) = −.48, p =.63. The degree to which the predictions explained the relationships between thermometer ratings and IAT scores was constant across the four conditions (all |t|’s < 1, n.s.). Also consistent with Study 3, the random components indicated that there was no meaningful variation in participants’ predictions of their IAT results (non-significant random error component for prediction), but a significant random error component for the thermometer ratings-IAT relationships.

Relationship between explicit thermometer ratings and IAT predictions

The lack of condition effects on accuracy is puzzling in many ways. In concert with the repeated finding that participants’ explicit thermometer ratings were only moderately related to their IAT scores, this finding poses the question of how participants differentiated between making an explicit thermometer rating and (explicitly) predicting an IAT score. In order to further investigate this process, we ran a series of additional analyses on the relationship between the thermometer ratings and IAT predictions. The main questions of interest were (1) the extent to which participants’ predictions were related to their initial explicit attitude ratings; (2) whether variance in participants’ IAT predictions that was not related to their explicit attitude ratings could be explained by their actual IAT results, as the previous findings would indicate; and, (3) whether these effects would be moderated by condition assignments. In other words, did all participants in all conditions deliberately indicate different attitudes when predicting their IAT results than when completing the thermometer ratings? And does the extent to which they indicated different predictions accurately reflect their IAT scores in all conditions?

Results of these analyses are presented in Table 7. As can be seen, there was a significant within-subjects relationship between IAT predictions and thermometer ratings, b=.47, t(151.00)=11.80, p<.001. And, although smaller in size, this relationship held when controlling for participants’ actual IAT scores, b=.37, t(143.08)=10.30, p<.001. Importantly, the simultaneous regression also confirmed that the variance in participants’ predictions that was left unexplained by the thermometer ratings could be explained by participants’ IAT scores to a substantial degree, b=.43, t(149.65)=14.97, p<.001. Crucially, results indicated that none of these effects were moderated by condition, all |t|’s <=1.09. That is, all participants in all conditions deliberately indicated different attitudes when they predicted their IAT results than when they completed the thermometer ratings, even those in the minimal-explanation/no-experience condition. And in all conditions, these differences accurately reflected participants’ actual IAT scores.

Table 7.

Study 4: The effect of explicit thermometer ratings on participants’ implicit-attitude predictions

| Parameters (DV: Score predictions) | Model 1 estimates | Model 2 estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Explicit thermometer ratings | .47*** | .37*** |

| Therm. × Explanation | −.01 | .00 |

| Therm. × Experience | .04 | .03 |

| Therm. × Explanation × Experience | −.01 | −.03 |

| IAT D-scores | .43*** | |

| IAT score × Explanation | −.01 | |

| IAT score × Experience | −.03 | |

| IAT score × Explanation × Experience | .02 | |

|

| ||

| Random effect variances | ||

| Explicit thermometer ratings | .122*** | .091*** |

| IAT D-scores | .011 | |

| Residuals | .517*** | .388*** |

|

| ||

| Goodness of fit | ||

| −2 log likelihood | 1815.75 | 1624.92 |

p<.001

All level-1 variables are standardized for each individual participant before they are entered in the analysis. “Explanation”, “Experience”, and “Explanation × Experience” refer to Level-2 (between-subject) predictors that are contrast-coded “−1” for no or minimal, and “1” for full explanation or experience, respectively. The interaction term is the product of these two codes.

Discussion

The purpose of Study 4 was to assess whether people would be able to predict their IAT results even without substantial explanation of the differences between implicit and explicit attitudes, and without experience with the implicit attitude measure. Results indicated that neither of these factors were necessary conditions for making accurate predictions about one’s implicit responses. Participants were as accurate in their predictions when they received minimal explanation and had no immediate experience with the implicit attitude measure, as they were with full training.