Abstract

Processes of coping with stress and the regulation of emotion reflect basic aspects of development and play an important role in models of risk for psychopathology and the development of preventive interventions and psychological treatments. However, research on these two constructs has been represented in two separate and disconnected bodies of work. We examine possible points of convergence and divergence between these constructs with regard to definitions and conceptualization, research methods and measurement, and interventions to prevent and treat psychopathology. There is clear evidence that coping and emotion regulation are distinct but closely related constructs in all of these areas. The field will benefit from greater integration of methods and findings in future research.

The skills needed to cope with stressful events and chronic adversity and to regulate emotions, including emotions that arise in response to stress, are fundamental and pervasive aspects of development that emerge over the course of childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. These abilities are implicated in normative development (e.g., Cole et al., 2004), distinguishing between resilience and risk for psychopathology (Compas & Reeslund, 2009; Curtis & Cicchetti, 2007), and adaptation to chronic and acute illness (Compas, Jaser, Dunn, & Rodriguez, 2012; DeSteno, Gross, & Kubzansky, 2013), among many other domains. The development of coping and emotion regulation skills reflects the coordination and interplay of processes of social, cognitive, affective, and brain development over these developmental periods. Further, coping and emotion regulation skills play a central role in transdiagnostic models of preventive interventions and psychological treatments for a range of psychological problems and disorders (Compas, Watson, Reising, & Dunbar, 2013; Mennin, Ellard, Fresco, & Gross, 2013; Trosper, Buzzella, Bennett, & Ehrenreich, 2009). In spite of their importance, and despite the many features they may share, research on these concepts has remained decidedly separate. As a result, the common vs. distinct elements of coping and emotion regulation remain poorly understood. We propose that the cumulative knowledge base in these fields will be stronger if we recognize both the shared and unique characteristics of these processes.

Several issues are central to advancing our understanding of the intersection of processes of coping and emotion regulation. First, a comparison of the definitions and conceptualizations of coping and emotion regulation is crucial for determining the shared vs. unique contributions of research on these processes. Second, comparison of the methods and measures used to study these processes can lead to greater integration of research and to the identification of ways in which findings from these two areas of research can complement and extend each other. And third, integration of research on interventions that involve the teaching of coping and emotion regulation skills designed to prevent or treat psychological disorders could lead to stronger, more targeted and more comprehensive interventions. We now address each of these issues.

Definition and Conceptualization

For research on coping and emotion regulation to continue to move forward, clear definitions and conceptualizations of each construct are needed to guide the development and selection of measures and research designs, and the integration of findings. Two questions are central to this task: (1) Are coping and emotion regulation distinct constructs, or are these constructs synonymous? (2) Is coping a subset of emotion regulation or is emotion regulation a subset of coping? One of the challenges in distinguishing between coping and emotion regulation has come from problems in defining each of these constructs separately (e.g., Cole et al., 2004; Compas et al., 2001; Eisenberg, 2010; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Skinner et al., 2003). Concerns have been raised about the lack of consensus regarding definitions of each of these constructs and, most importantly, there has been little or no systematic examination of the consistencies and differences in the definitions between coping and emotion regulation (Compas, Jaser, & Benson, 2009). In Table 1, we present several of the most widely used definitions of both constructs to facilitate the identification of similarities and differences.

Table 1.

Definitions of coping and emotion regulation.

| Coping | |

| Lazarus & Folkman (1984) | “Constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (p.141). |

| Lazarus (2004) | “Efforts to manage adaptational demands and the emotions they generate” (p. 10). |

| Compas et al. (2001) | “Conscious and volitional efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, behavior, physiology, and the environment in response to stressful events or circumstances” (p. 89). |

| Skinner & Wellborn (1994) | “Action regulation under stress”, including the ways that people “mobilize, guide, manage, energize, and direct behavior, emotion, and orientation, or how they fail to do so” under stressful conditions (p. 113). |

| Eisenberg et al. (1997) | “Regulatory processes in a subset of contexts—those involving stress” (p. 42). |

| Emotion Regulation | |

| Thompson (1994) | “The extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluation, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features, to accomplish one’s goals” (p. 27–28). |

| Gross (1998 / 2013) | “The process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience these emotions” (p. 275). “Emotion regulation requires the activation of a goal to up- or down-regulate either the magnitude or duration of a specific emotional response” (p. 1). |

| Cicchetti et al. (1991) | “[T]he intra- and extraorganismic factors by which emotional arousal is redirected, controlled, modulated, and modified to enable an individual to function adaptively in emotionally arousing situations” (p. 15). |

| Eisenberg et al. (2007) | “[P]rocesses used to manage and change if, when, and how (e.g., how intensely) one experiences emotions and emotion-related motivational and physiological states, as well as how emotions are expressed behaviorally” (p. 288). |

Coping

Perhaps the most widely cited definition of coping continues to be that of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), almost 30 years since it was first presented (see Table 1). This definition highlights several features of coping, including the role of both cognitive and behavioral processes and a focus on responses to demands that are appraised as stressful, in that they tax or exceed the resources of the individual. With an increasing focus on coping processes in children and adolescents, several definitions following the seminal work of Lazarus and Folkman have shifted toward a focus on childhood and adolescence (Compas et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Guthrie, 1997; Skinner et al., 2003). For example, Skinner and Wellborn (1994) have conceptualized coping as “action regulation under stress” and defined it as “how people mobilize, guide, manage, energize, and direct behavior, emotion, and orientation, or how they fail to do so” (p. 113). More recently, Compas et al. (2001) defined coping as, “conscious volitional efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, behavior, physiology, and the environment in response to stressful events or circumstances” (p.89). However, in spite of their increased emphasis on coping in children and adolescents, these definitions do not include explicit developmental elements.

These recent definitions represent increasing consensus in defining coping and share several features. First, similar to the earlier perspective of Lazarus and Folkman, these definitions focus on processes that occur exclusively in response to acute or chronic stressful events or circumstances; i.e., coping refers to processes that are enacted in response to stress. Second, these definitions focus on effortful processes in response to stress. The focus on effort implies that coping is controlled, purposeful, within conscious awareness, and goal-directed. Third, there has been an increasing emphasis on coping as a form of regulation in response to stress. This emphasis on regulation has broadened the scope of coping since the earlier work of Lazarus and Folkman to include more than the “management” of stressful demands. The regulation of a wider range of functions, including emotion, behavior, cognitions, physiology, and the environment, is now included within the sphere of coping. In spite of this increasing consensus, however, there is continued debate about the underlying structure of coping and the subtypes that best capture the varied nature of coping responses. For example, Skinner et al. (2003) identified over 400 subtypes of coping that have been studied, noting that progress in determining the structure of coping has been slow. Thus, while some progress has been made in clarifying the conceptualization of coping in the broadest sense, there continues to be confusion about the organization and subtypes of coping.

Emotion regulation

Several definitions of emotion regulation have been offered, reflecting a promising degree of consensus regarding the core features of emotion regulation (see Table 1). An influential perspective is offered by Gross (1998), who defined emotion regulation as, “ the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions” (p. 275) and more recently as the process by which individuals influence the occurrence, timing, nature, experience, and expression of their emotions (Gross, 2013). Similarly, Eisenberg, Hofer, and Vaughn (2007) defined emotion regulation as, “processes used to manage and change if, when, and how (e.g., how intensely) one experiences emotions and emotion-related motivational and physiological states, as well as how emotions are expressed behaviorally” (p. 288). Emotion regulation is organized around specific emotions (e.g., sadness, fear, anger) and includes efforts to up- or down-regulate both positive and negative emotions. Conceptualizations of emotion regulation include both intrinsic and extrinsic processes to accomplish goals or function adaptively (Cicchetti, Ackerman, & Izard, 1995; Thompson, 1994). Similar to the state of research on coping, a number of different emotion regulation strategies have been identified and there is not consensus on the underlying structure of emotion regulation (e.g., Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). And similar to the wide range of strategies that are included within the framework of coping, the number of emotion regulation strategies continues to increase in number and breadth. For example, Aldao et al. (2010) include problem solving as one example of emotion regulation, even though the explicit intent of such strategies is not the regulation of emotions.

Coping and emotion regulation: Common elements

Examination of the definitions presented in Table 1 suggests that the concepts of coping and emotion regulation share several important elements. First, both coping and emotion regulation are conceptualized as processes of regulation. As noted by Eisenberg et al. (1997) not only is coping “motivated by the presence or expectation of emotional arousal (generally resulting from stress or danger),” but “many forms of coping are very similar to types of regulation discussed in the emotion regulation literature” (p. 288). Similarly, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck (2007) conceptualize coping as “action regulation under stress.” In their conceptualization of coping, Compas et al. (2001) note that regulation includes efforts to initiate, terminate or delay, modify or change in form or content, redirect the focus, or modulate the amount or intensity of a thought, behavior, emotion, or physiological response. By definition, regulatory processes are also at the core of emotion regulation. For example, Thompson (1994) noted that emotion regulatory processes include monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensity and duration. Aldao et al. (2010) noted that individuals deploy regulatory strategies to modify the magnitude and/or type of their emotional experience or the emotion-eliciting event.

Second, both coping and emotion regulation include controlled, purposeful efforts. This is reflected in the early work of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), who viewed coping as purposeful responses that are directed toward resolving the stressful relationship between the self and the environment. These responses are represented in goal-directed processes in which the individual orients thoughts and behaviors toward the goals of resolving the source of stress and managing emotional reactions to stress. Compas et al. (2001) recognize that both automatic and controlled processes are enacted in response to stress, but argue that coping is limited to responses that are volitional, purposeful, within conscious awareness, and goal directed. Similarly, Gross (2013) views emotion regulation as part of a continuum from automatic processes to explicit, conscious, effortful, and controlled regulation. Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema (2010) note that emotion regulation includes processes through which individuals consciously modulate their emotions. As we discuss below, however, the role of automatic processes is a point of distinction between coping and emotion regulation.

Third, coping includes emotion regulation under stress. Because emotion regulation is conceptualized as an ongoing process that occurs under both stressful and non-stressful circumstances (Gross, 2013), coping can be conceived as a special case of emotion regulation under stress (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010). Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck (2007) noted that, “all strategies of emotion regulation can be considered ways of coping” (p. 122). Therefore, the intersection or common ground of coping and emotion regulation involves efforts to regulate emotions in response to stressful events and circumstances.

And fourth, coping and emotion regulation are conceptualized as temporal processes that unfold and may change over time. For example, although most forms of coping are viewed as responses to stressful events and circumstances, anticipatory coping has been described as a process that occurs prior to the onset of a stressor to prevent, forestall, or reduce the severity of the stressful event (e.g., Aspinwall & Taylor, 1997). Similarly, emotion regulation can include modification of situations in advance of the arousal of an emotion as well as modification of emotions once they arise. For example, John and Gross (2004) consider cognitive-reappraisal to be an antecedent-focused strategy, such that it is employed before the emotion response tendencies have been activated. On the other hand, emotional suppression is considered to be a response-focused strategy, such that it is employed after the emotion has been experienced, modifying the behavioral expression of the emotion.

Coping vs. emotion regulation: Distinguishing features

These similarities notwithstanding, coping and emotion regulation are distinct in several ways. First, emotion regulation includes both controlled and automatic processes whereas coping includes only controlled volitional processes. Gross (2013) conceptualizes emotion regulation as including both automatic and controlled processes that may be conscious or non-conscious. Although some conceptualizations of coping have included automatic processes as a part of coping (Somerfield & McRae, 2000), most definitions distinguish coping as controlled responses to stress from automatic processes reflected in stress reactivity (e.g., Compas et al., 2001).

Second, coping exclusively refers to responses to stress, whereas emotion regulation encompasses efforts to manage emotions under a much wider range of situations and in reaction to a wider range of stimuli (Compas et al., 2001; Folkman & Mosowitz, 2004). Emotion regulation includes processes directed towards positive and negative emotions that arise under normative, non-stressful circumstances (e.g., Webb et al., 2012). Therefore, it follows that emotion regulation occurs in a much wider range of circumstances than only those that are stressful. For example, emotion regulation involves responses to non-stressful circumstances such as suppressing a laugh when seeing someone make a mistake or managing a strong emotion in response to a film or a book (Webb et al.) Positive and negative emotions arise in the course of ongoing encounters in daily life, the majority of which do not represent sources of stress for the individual. Although coping is limited to responses to stress, the boundary between stressful and non-stressful circumstances is admittedly blurry (e.g., Grant et al., 2004).

Third, as highlighted in the definition offered by Thompson (1994) presented in Table 1, emotion regulation may include both intrinsic processes (i.e., emotion that is regulated by the self) and extrinsic processes (i.e., emotion that is regulated by an outside factor). Although coping may involve extrinsic factors (e.g., social support), it is only carried out by the person experiencing stress. In contrast, some aspects of emotion regulation can be managed by another person, particularly early in development (e.g., a parent providing solace and soothing for a young child).

Fourth, research on emotion regulation and coping has focused on different developmental stages. While extensive research has examined emotion regulation in infants and young children, coping has almost exclusively been studied in later childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Research on the developmental course of these regulatory strategies is still in its early stages (for reviews, see Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2011), and how the structure of coping may change across different developmental periods with the emergence of new capacities (e.g., language, locomotion, executive function) is not well understood. Although infants and young children experience stressors and engage in regulatory processes, many of these responses involve direct assistance and comfort from caregivers and the extent to which young children’s own behaviors (e.g., sucking, gaze aversion) are conscious and volitional responses is not clear. Consequently, coping research has mainly focused on childhood, adolescence, and adulthood when the cognitive and behavioral skills needed to engage in more complex, effortful, and goal-directed regulatory behaviors (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, distraction, avoidance) emerge. However, future research should more closely and systematically examine the use of regulatory strategies in infants and young children to better understand the developmental course of coping and emotion regulation strategies.

Summary

To return to our two questions about coping and emotion regulation, current conceptualizations would suggest that they are not synonymous. That is, coping and emotion regulation are closely related but distinct constructs. However, the relationship between these constructs is complex. On the one hand, emotion regulation is a broader construct than coping as it encompasses ongoing emotional events whereas coping is a subset of emotion regulation that is enacted in response to stressful events or circumstances. On the other hand, coping includes a broader array of regulatory efforts than emotion regulation within the context of stressful encounters and emotion regulation is a subset of responses to stress. Thus, coping is both broader and more specific in its focus than emotion regulation. This suggests that an important focus of research could be the relations between coping that is enacted under stress and emotion regulation under non-stressful circumstances. For example, what is the association between the ongoing regulation of emotions in daily life and coping that is enacted in response to stress? And what is the developmental sequence between emotion regulation and coping skills?

Measurement and Methodology

Reflective of both their shared and distinct features, research on coping and emotion regulation has involved both similar and different methods and measures to study these processes. Extensive research using questionnaires has assessed both coping with stress and the regulation of emotions as they occur during ongoing transactions with the environment. However, processes of emotion regulation have been uniquely studied using experimental designs in which emotions are either elicited using arousing stimuli or through instruction to participants to experience specific emotions. Although these experimental methods offer important insights into emotion regulation and coping (e.g., Gross 1998; Gross & John, 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Webb et al., 2012), we focus here on questionnaire measures as a way to highlight similarities in the measurement of these two constructs.

In Table 2, we present items on two questionnaires selected as examples of current measures of each construct, the Responses to Stress Questionnaire (RSQ; Connor-Smith et al., 2000) and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003). Although the RSQ measures both controlled and automatic responses to stress, we focus here on the portion of the measure that reflects controlled responses to stress, or coping strategies. Similarly, the ERQ measures conscious, controlled efforts to regulate emotion. When we compare these two measures of emotion regulation and coping at the item level, it becomes clear that there is considerable overlap. Two key examples of this overlap emerge in measures of both coping and emotion regulation as strategies that are used across developmental stages, demonstrate associations with psychopathology, and are capable of change in response psychological interventions. These are cognitive reappraisal/restructuring and emotional suppression/expression.

Table 2.

Measurement of Coping and Emotion Regulation: Similarities Across Items on the RSQ and ERQ on the Constructs of Cognitive Reappraisal and Emotional Expression/Suppression

| Cognitive Restructuring / Cognitive Reappraisal | |

|---|---|

| RSQ Items | ERQ Items |

| When I’m faced with (stressor), I think about the things that I am learning from the situation, or something good that will come from it. | When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about. |

| I tell myself that things could be worse. | When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about. |

| I tell myself that it doesn’t matter, that it isn’t a big deal. | When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm. |

| ----- | When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation. |

| ----- | I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in. |

| ----- | When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation. |

| Emotional Expression / Suppression | |

| RSQ Items | ERQ Items |

| I keep my feelings under control when I have to, then let them out when they won’t make things worse. | I keep my emotions to myself. |

| I get help from other people when I’m trying to figure out how to deal with my feelings. | When I am feeling positive emotions, I am careful not to express them. |

| I do something to calm myself down (e.g., take a deep breath, listen to music, walk). | I control my emotions by not expressing them. |

| I let someone know how I feel (e.g., parent, teacher, friend). | When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them |

| I get sympathy, understanding, or support from someone. | ----- |

| I let my feelings out (e.g., by writing in a journal, punching a pillow). | ----- |

Note. RSQ: Responses to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith et al., 200). ERQ: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003).

Cognitive reappraisal/restructuring

Cognitive reappraisal/restructuring is defined as “a form of cognitive change that involves construing a potentially emotion-eliciting situation in a way that changes its emotional impact” (Lazarus & Alfert, 1964). More recently, Gross and Thompson (2007) defined emotion regulation as “a cognitive-linguistic strategy that alters the trajectory of emotional responses by reformulating the meaning of a situation” (p. 14). In research on coping the strategy of cognitive restructuring as measured on the RSQ includes items such as, “I tell myself that things could be worse,” and “I think about the things that I am learning from the situation” (Connor-Smith et al., 2000). The ERQ, similarly, includes items such as, “When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm,” and “When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation” (Gross & John, 2003). Although there are semantic differences in these items, they all reflect efforts to change one’s thoughts to address a stressor or one’s emotions.

In research on both coping and emotion regulation, cognitive reappraisal/restructuring is associated with better psychological adjustment, including lower symptoms of depression and anxiety. In emotion regulation research, cognitive reappraisal/restructuring on the ERQ is generally related to higher levels of positive emotion and lower levels of negative emotion (Gross & John, 2003). In a recent meta-analysis of emotion regulation and psychopathology, Aldao et al. (2010) found that cognitive reappraisal/restructuring was associated with fewer symptoms of psychopathology as reflected in a small but significant negative effect (mean d = −.14). And in emotion regulation research, cognitive reappraisal/restructuring on the ERQ is generally related to higher levels of positive emotion and lower levels of negative emotion (Gross & John, 2003).

Likewise, studies using the RSQ have shown that secondary control coping strategies, which includes cognitive reappraisal/restructuring, are related to better adjustment (e.g., fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression; Compas et al., 2006; Jaser et al., 2005). One limitation of this measure is that cognitive restructuring is grouped with other strategies that are involved in adapting to a stressor or one’s emotional response to a stressor (i.e., positive thinking, acceptance, and distraction) and is analyzed as part of a higher-order factor, secondary control coping. As such, no analyses have been conducted at the specific level of cognitive reappraisal/restructuring, and we cannot determine whether that particular strategy relates to better adjustment. Conversely, the problem with only measuring cognitive reappraisal/restructuring is that other important information about closely related strategies of secondary control coping might be lost.

In one of the only studies to use both the RSQ (as a measure of coping with interpersonal stress) and the ERQ, Andreotti et al. (2013) found that cognitive restructuring on the RSQ and cognitive reappraisal on the ERQ were significantly correlated, but this effect was only moderate in magnitude (r = .33). Further, cognitive reappraisal as measured by the ERQ was more strongly associated with positive affect, while secondary control coping (including cognitive restructuring) was more strongly associated with negative affect, including symptoms of depression and anxiety (Andreotti et al.). These associations are striking in light of one important difference between the two measures-- the RSQ asks what people do in response to a specific domain of stress (in this case, interpersonal stressors), whereas the ERQ asks individuals what they do in response to their emotions (e.g., sadness). While the process of cognitive reappraisal is similar, the goal of the actions are different – the ERQ is focused on emotions, while the RSQ is focused on a stressor.

Emotional expression/suppression

Emotional expression (e.g., letting someone know how you are feeling) and emotional modulation (e.g., keeping feelings under control until an appropriate time to express them) are constructs found in coping measures that are similar to emotional expression/suppression constructs found in emotion regulation measures. For example, the RSQ strategy of emotional modulation includes items such as, “I keep my feelings under control when I have to, then let them out when they won’t make things worse” (Connor-Smith et al., 2000). Similarly, the ERQ strategy of emotional suppression, “I keep my emotions to myself” (Gross & John, 2003) asks about individuals’ attempts to keep the expression or display of emotions under control. Both measures include scales that focus on emotion, but while the ERQ is focused on suppression of the expression of emotion, the RSQ is focused on the modulated expression of emotion.

The suppression of the expression of emotions in real-world settings has been linked with increases in negative emotions. For example, in their meta-analysis of emotion regulation and psychopathology, Aldao and colleagues (2010) found that emotional suppression was significantly associated with greater symptoms of psychopathology (d = .34). It is hypothesized that this is due to people’s awareness of lack of authenticity in suppressing the expression of a feeling (Gross & John, 2003). In the coping literature, strategies related to emotional expression and emotional modulation have often been considered part of the broader category of emotion-focused coping which has been associated with poorer adjustment (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). However, confirmatory factor analyses of the RSQ indicate that these strategies (emotional expression and emotional modulation) load together with problem solving as part of the primary control coping factor (Benson et al., 2011; Connor-Smith et al., 2000; Compas et al., 2006; Wadsworth et al., 2004), and several studies have found that primary control coping is associated with lower symptoms of anxiety and depression and other internalizing symptoms (e.g., Campbell et al., 2009; Jaser & White, 2011).

Perhaps the difference in the direction of effects of emotional modulation/emotional expression found in coping measures and emotional suppression is due to an important distinction between the constructs – while emotional suppression describes individuals’ attempts to suppress the expression of negative emotions, emotional modulation acknowledges that individuals may need to express their emotions at a later, potentially more appropriate time. The work of Stanton and colleagues on emotional approach coping, which includes strategies related to expressing emotion and emotional processing, is instructive in this regard. For example, Hoyt, Stanton et al. (2013) found that emotional approach coping was associated with lower symptoms of psychological distress than earlier measures of emotion-focused coping, which often included items related to letting feelings out inappropriately (e.g., crying, worrying). In a longitudinal study, emotional processing and emotional expression were found to predict fewer symptoms of depression and higher satisfaction with life (Stanton et al., 2000). This is in line with results showing that expressive writing about emotions reduces symptoms after traumatic events (e.g., Smyth & Pennebaker, 1999).

In spite of the active lines of research using questionnaires to assess coping and emotion regulation, this method has been the target of significant criticism (see Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004, for a review) due to the inherent limitations in the use of self-reports to assess both coping or emotion regulation and symptoms of distress or psychopathology (i.e., shared method variance due to use of self-reports, possible reporting biases, confounding of items, problems with recall of coping and emotions). However, recent work reflects progress in the use of questionnaires to assess coping. The use of cross-informant reports from children and parents offers supporting evidence that the constructs measured by these questionnaires do capture important aspects of coping. For example, significant cross-informant correlations have been found in children’s self-reports and parents’ reports of the way in which children cope with stress related to parental depression (Jaser et al., 2005). Similarly, the way in which children cope with chronic pain has been measured with both parent- and self-report and found to predict cross-informant reports of anxiety and depression using latent indicators of both constructs in structural equation analyses (Compas et al., 2006). These studies demonstrate that coping can be effectively measured using questionnaires and can achieve convergence across multiple informants. Further, coping questionnaires have been validated with cognitive and physiological measures (e.g., Campbell et al., 2009; Dufton et al., 2011). For example, Campbell et al. found that measures of executive function (assessing the domains of working memory, cognitive flexibility, behavioral inhibition, and self-monitoring) were significantly related to primary control coping, secondary control coping, and disengagement coping in childhood cancer survivors. In addition, Andreotti and colleagues (2013) showed significant associations between measures of working memory and secondary control coping (including cognitive restructuring).

Summary

Similar to the considerable level of coherence in the definitions of these distinct constructs, examination of measures of coping and emotion regulation further highlights both convergence and divergence between these constructs. More studies are needed using measures from both fields to better understand the overlap between these constructs. Careful measurement of coping and emotion regulation is important, as we turn to the interventions designed to improve these skills.

Preventive Interventions and Psychological Treatments

The development of interventions to enhance coping and emotion regulation skills represents one of the most important applications of these constructs. These interventions have all been included within the general family of cognitive-behavioral interventions; have been designed for children, adolescents, and adults; and have focused on both the prevention and treatment of psychological problems (e.g., Compas et al., 2013; Mennin et al., 2013). In light of the considerable overlap in definitions, conceptualizations, and measures of coping and emotion regulation, it is not surprising that coping and emotion regulation interventions share many common features. Below, we review several interventions aimed at improving the concepts highlighted above: cognitive reappraisal/restructuring and emotional expression/suppression (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Skills Taught Across Coping and Emotion Regulation Interventions

| Coping skills taught in interventions | ER skills taught in interventions |

|---|---|

| Acceptance (Compas et al. 2009) | Emotion Awareness (Suveg et al., 2009); Acceptance (Fresco et al., 2013) |

| Distraction (Compas et al., 2009) | Walking away from a distressing situation, participating in a play activity, physical exercise, playing music, chores, projects (Kovacs, 2006) |

| Cognitive Restructuring (Compas et al., 2009) | Using imagery to counter dysphoric emotion, helpful “self talk,” focusing attention on neutral or positive topics, changing thoughts that tend to lead to sad affect (Kovacs, 2006); Cognitive change (Fresco et al., 2013) |

| Positive Thinking (Compas et al., 2009) | Receiving physical comfort, talking to a trusted adult about dysphoria, playing or interacting with peers, and effectively recruiting social regulators (by using explicit language) (Kovacs, 2006) |

| ----- | Problem Solving (Suveg et al., 2009) |

| Scheduling and participating in mood enhancing activities (Compas et al., 2009) | ----- |

| ----- | Relaxation (Suveg et al., 2009) |

Interventions to enhance coping skills

A recent example of a coping skills interventions focuses on teaching secondary control coping skills to children of depressed parents, including cognitive reappraisal (positive thinking), acceptance, and distraction to children of depressed parents (Compas et al., 2009, 2010, 2011). These coping skills (as measured by both child self-reports and parent reports) increased in children who participated in the intervention as compared to those in a control condition, and changes in children’s use of secondary control coping mediated (i.e., accounted for) subsequent changes in children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Compas et al., 2010). This study provides strong evidence that teaching coping skills is an important, active ingredient in this preventive intervention.

Interventions to enhance emotion regulation skills

A recent intervention developed by Kovacs and colleagues (2006), Contextual Emotion-Regulation Therapy (CERT), targets emotion-regulation in childhood depression. The intervention targeted cognitions as one of several emotion regulation domains, and cognitive skills included “conjuring up some image to counter the dysphoric emotion, helpful ‘self-talk’… or changing how you think about what makes you sad”. In addition, CERT targeted behavioral, biological, and social/interpersonal emotion regulation strategies, teaching a number of skills, including participating in a play activity, physical exercise, or other projects, receiving physical comfort, talking to a trusted adult, or talking with peers. Similarly, Suveg et al. (2009) developed an emotion-regulation treatment for child anxiety, Emotion-Focused CBT (ECBT). ECBT teaches youth cognitive reappraisal skills common to CBT in treatment for child anxiety, as well as problem solving and relaxation training.

Mennin and colleagues describe the development of emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adults (Fresco et al., 2013; Mennin et al., 2013). Based in cognitive regulation skills training and experiential exposure to promote contextual learning. The three main emotion regulation skills taught are acceptance and allowance, cognitive distancing (decentering), and cognitive change (reframing) (Fresco et al., 2013). Acceptance is taught through an in-session exercise designed to increase clients’ awareness of emotional, tactile, and cognitive sensations. Cognitive distancing or decentering is taught through perspective taking, allowing the client to deliberately respond “counteractively” instead of mindlessly responding reactively (Fresco et al.). In the cognitive change component of the treatment clients are encouraged to adopt a “self-compassionate” reappraisal stance by imagining they are telling a very caring, interested, compassionate individual about their difficult thoughts and feelings and reminding themselves of their strengths and coping abilities. By noticing their self-critical thoughts clients are encouraged to “soften” them when they arise by invoking of alternative, self-validating statements (Fresco et al.).

Summary and Future Directions

Coping with stress and the regulation of emotions are important psychological processes that are represented in two vibrant areas of theory, research and clinical application. There is now considerable evidence that these two constructs share many features in their basic definition and conceptualization, measurement, and interventions to enhance skills in the prevention and treatment of psychopathology. However, while coping and emotion regulation are closely linked, they are not synonymous, suggesting that there is potential benefit in examining these separate constructs together in future research.

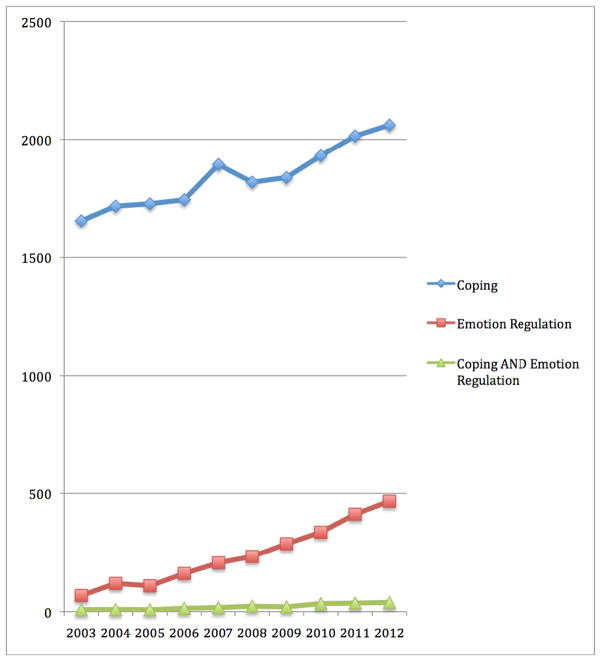

Given the substantial overlap between these constructs, it is important to examine the degree to which research has examined possible connections between them. Both coping and emotion regulation are the focus of highly active areas of research. Several authors have noted that coping is a historically older construct, reflecting over 50 years of research (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004), whereas emotion regulation has emerged more recently but has experienced a rapid ascension to an active area of research (Gross, 2013). In spite of the considerable degree of overlap, this work has largely proceeded separately with little evidence of dialogue between these two lines of research. This is clearly reflected in the number of citations to these constructs over the last 10 years. Based on a PsycINFO search of the key words “coping” and “emotion regulation” from 2003 through 2012, the number of citations for coping has increased annually from 1,656 in 2003 to 2,061 in 2012, and the citations for emotion regulation have increased from 68 to 467 (see Figure 1). However, citations that included both terms have increased from only 8 in 2003 to 39 in 2012. Thus, citations that included both coping and emotion regulation as key terms reflect only 1% of the total publications on these processes in the past 10 years (i.e., only 208 articles out of 20,804 articles in the last 10 years included the identifiers of coping and emotion regulation), demonstrating that researchers continue to examine these two constructs separately.

Figure 1.

Citations in PsycInfo including coping and emotion regulation as key terms from 2003 through 2012.

Based on the findings reviewed above, we believe that it is time for researchers who study coping and emotion regulation to break down the barriers between these two lines of research and further examine the possible linkages between these constructs. This can take at least two forms, one at a broad, macro level and the other at a more focused, micro level. At the broadest level, it is important to test the developmental pattern and possible sequences in the emergence of skills to cope with stress and regulate emotions over the course of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. We propose the ability to regulate emotions under normative conditions of daily life emerges early in childhood and precedes the ability to bring these skills, and the ability to regulate other aspects of cognition and behavior, into action in response to stressful events and conditions of chronic adversity. Such a sequence would suggest that emotion regulation skills provide a foundation that individuals can learn to call upon when faced with the heightened levels of arousal that accompany exposure to stress.

At a more micro level we hypothesize that coping efforts that are initiated in response to a defined stressful event are supported by efforts to regulate emotions before and after a stressful encounter. Poor emotion regulation skills prior to stress may contribute to the onset or occurrence of dependent stressful events; i.e., stressors that are at least in part the result of actions by the individual (e.g., Conway, Hammen, & Brennan, 2012). And after the termination of a stressful event, problems in the regulation of residual negative emotions following the event could lead to heightened and prolonged negative emotions even in the absence of stress, leaving the individual vulnerable. For such individuals, everyday, non-stressful encounters may trigger sustained periods of distress. These are but two examples of the kinds of hypotheses that will come into focus if researchers make a more concerted effort to take an integrated approach to the study of coping and emotion regulation.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti C, Thigpen JE, Dunn MJ, Watson KH, Potts J, Reising MM, Robinson KE, Rodriguez EM, Roubinov DM, Luecken L, Compas BE. Cognitive reappraisal and secondary control coping: Associations with working memory, positive and negative affect, and symptoms of anxiety/depression. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 2013;26:20–35. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.631526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. A stitch in time: Self regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:417–436. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MA, Compas BE, Layne CM, Vandergrift N, Pasalic H, Katalinski R, Pynoos RS. Measurement of post-war coping and stress responses: A study of Bosnian adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32:323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LK, Scaduto M, Van Slyke D, Niarhos F, Whitlock JA, Compas BE. Executive function, coping and behavior in survivors of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:317–327. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a specific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ackerman BP, Izard CE. Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Ganiban J, Barnett D. Contributions from the study of high-risk populations to understanding the development of emotion regulation. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1991. pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Andreotti C. Risk and resilience in child and adolescent psychopathology: Processes of stress, coping and emotion regulation. In: Beauchaine TP, Hinshaw S, editors. Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2. New York: Wiley; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Boyer MC, Stanger C, Colletti RB, Thomsen AH, Dufton LM, Cole DA. Latent variable analysis of coping, anxiety/depression, and somatic symptoms in adolescents with chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1132–1142. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, Cole DA, Reeslund KL, Fear J, Hardcastle J, Keller G, Rakow A, Garai E, Merchant MJ, Roberts L. Coping and Parenting: Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:623–634. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth M. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Progress, problems, and potential. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, Champion A, Reeslund KL, McKee L, Fear JM, Colletti CJM, Hardcastle E, Merchant MJ, Roberts L, Potts J, Garai E, Coffelt N, Roland E, Sterba SK, Cole DA. Randomized clinical trial of a family cognitive behavioral preventive intervention for children of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1009–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Thigpen JC, Keller G, Hardcastle EJ, Cole DA, Potts J, Haker K, Rakow A, Colletti C, Reeslund K, Fear J, Garai e, McKee L, Merchant MJ, Roberts L. Family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for families of depressed parents: 18- and 24-month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:488–499. doi: 10.1037/a0024254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Benson M. Coping and emotion regulation: Implications for understanding depression during adolescence. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Depression. New York: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM. Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:455–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Reeslund KL. Processes of risk and resilience: Linking contexts and individuals. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescence. 3. New York: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Watson KH, Reising MM, Dunbar JP. Stress and coping: Transdiagnostic processes in child and adolescent psychopathology. In: Ehrenrich-May J, Chu B, editors. Transdiagnostic Mechanisms and Treatment Approaches of Youth Psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary responses to stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CC, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Expanding stress generation theory: Test of a transdiagnostic model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:754–766. doi: 10.1037/a0027457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis WJ, Cicchetti D. Emotion and resilience: A multilevel investigation of hemispheric electroencephalogram asymmetry and emotion regulation in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:811–840. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno D, Gross JJ, Kubzansky L. Affective science and health: The importance of emotion and emotion regulation. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):474–486. doi: 10.1037/a0030259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufton LM, Dunn MJ, Slosky LS, Compas BE. Self-reported and laboratory-based responses to stress in children with pain and anxiety. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36:95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK. Coping with stress: The roles of regulation and development. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, Vaughan J. Effortful control and its socioemotional consequences. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Ritter M. Emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20:282–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY. Stressors and child/adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:412–425. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward. Emotion. 2013;13:359–365. doi: 10.1037/a0032135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MA, Stanton AL, Irwin MR, Thomas KS. Cancer-related masculine threat, emotional approach coping, and physical functioning following treatment for prostate cancer. Health Psychology. 2013;32:66–74. doi: 10.1037/a0030020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Langrock AM, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson M, Reeslund K, Champion JE, Compas BE. Coping with the Stress of Parental Depression II: Adolescent and Parent Reports of Coping and Adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:193–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, White LE. Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011;37:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Lopez-Duran NL. Contextual emotion regulation therapy: A developmentally based intervention for pediatric depression. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;21:327–343. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and lifespan development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Sherrill J, Geroge CJ, Pollack M, Tumuluru RV, Ho V. Contextual emotion-regulation therapy for childhood depression: Description and pilot testing of a new intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:892–903. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000222878.74162.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Alfert E. Short-circuiting of threat by experimentally altering cognitive appraisal. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1964;69:195–205. doi: 10.1037/h0044635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Ellard KK, Fresco DM, Gross JJ. United we stand: Emphasizing commonalities across cognitive-behavioral therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:234–248. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviv T, Wadsworth ME. The efficacy of a pilot prevention program for children and caregivers coping with economic strain. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34:216–228. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(2):216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Wellborn JG. Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. In: Featherman D, Lerner R, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-Span Development and Behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 91–133. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Pennebaker JW. Sharing one’s story: Translating emotional experiences into words as a coping tool. In: Snyder CR, editor. Coping: The psychology of what works. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Somerfield MR, McRae RR. Stress and coping research: Methodological challenges, theoretical advances, and clinical applications. American Psychologist. 2000;55:620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burge A, Twillman R, Cameron CL, Bishop M, Collins CA, Kirk SB, Soroworski LA. Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:875–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Sood E, Comer JS, Kendall PC. Changes in emotion regulation following cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:390–401. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Biological and behavioral aspects. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 59. 1994. pp. 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosper SE, Buzzella BA, Bennett SM, Ehrenreich JT. Emotion regulation in youth with emotional disorders: Implications for a united treatment approach. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:234–254. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Reickmann T, Benson M, Compas BE. Coping and responses to stress in Navajo adolescents: Psychometric properties of the Responses to Stress Questionnaire. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:391–411. [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Miles E, Sheeran P. Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(4):775–808. doi: 10.1037/a0027600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]