Abstract

Fertility throughout East Asia has fallen rapidly over the last five decades and is now below the replacement rate of 2.1 in every country in the region. Using South Korea as a case study, we argue that East Asia's ultra-low fertility rates can be partially explained by the steadfast parental drive to have competitive and successful children. Parents throughout the region invest large amounts of time and money to ensure that their children are able to enter prestigious universities and obtain top jobs. Accordingly, childrearing has become so expensive that the average couple cannot afford to have more than just one or two children. The trend of high parental investment in child education, also known as ‘education fever’, exemplifies the notion of ‘quality over quantity’ and is an important contributing factor to understanding low-fertility in East Asia.

Keywords: Education Fever, Korea, Low fertility, Quality-Quantity Trade-Off, East Asia

Background

Recent fertility increases in Europe over the last 10 years have somewhat ameliorated the concerns about low fertility and its implications for population ageing and declining population sizes. These increases in total fertility rate (TFR) and related fertility measures have been interpreted by many as offering a more optimistic outlook for the demographic trends in Europe and some other highly developed countries. Specifically, fertility rates in all but one European country have emerged from ‘lowest-low’ fertility (TFR of 1.3 or less), and many countries seem likely to experience further fertility increases (Kohler, Billari, & Ortega, 2002; Goldstein, Sobotka, & Jasilioniene, 2009; Myrskylä, Kohler, & Billari, 2009). These increases have been documented in both period and cohort fertility. While some European countries (e.g. Sweden, Norway, and Denmark) have regained TFR levels near replacement level fertility after sustained periods of lower fertility, others countries persist with relatively low fertility levels—even if it is higher than the TFR levels observed in the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Spain, Italy, and Portugal). Although low fertility in Europe will, in all likelihood, continue to be an important topic for social scientists and policy makers, from today's perspective, it seems reasonable to predict that most countries in Europe, as well as the continent as a whole, have experienced their ‘natality nadir’ in terms of the all-time lowest TFR levels, and that future fertility is likely to be higher—and in many cases, substantially higher—than the levels observed during the last 20 years.1 One manifestation of this expectation, for instance, is reflected in the most recent UN World Population Prospects, which assume a long-term convergence of TFR to near-replacement level, a revision from earlier forecasts that assumed a convergence to a persistent below-replacement TFR (United Nations, 2011).

The renewed modest optimism towards the future of European fertility stems from recent literature pointing to childbearing postponement (a form of tempo change) as the culprit for Europe's natality nadir (Goldstein et al., 2009; Kohler et al., 2002; Kohler, Billari, & Ortega, 2006) and analyses that suggest that TFR levels might be pushed upward through quantum increases in the most advanced countries (Myrskylä et al., 2009), especially when high levels of development are combined with high levels of gender equality (Myrskylä, Kohler, Billari, 2011). According to Goldstein et al. (2009, abstract), ‘formerly lowest-low fertility countries will continue to see increases in fertility as the transitory effects of shifts to later childbearing become less important’. This trend may be reinforced if there are indeed quantum increases that elevate fertility from very low levels as countries reach higher development levels. These claims are supported by new cohort fertility forecasts from Myrskylä, Goldstein, and Cheng (2012) which show that cohort fertility has stopped falling and will likely increase in many developed countries, including places most known for and frequently studied because of their low fertility such as Italy, Germany, and Russia.

Like Europe, period fertility in East Asian countries has probably reached its all-time low. Key demographic indicators provide evidence that tempo changes due to postponed marriage and childbearing have had, and continue to have, profound impacts on the region's low fertility rate. The mean age of first marriage, which has risen across the region over the last 15 years, is likely attributable to the fact that East Asian women now study longer and enter the labour force at a later age. Given the close link between marriage and childbearing in East Asia, the age at first birth has essentially changed in tandem with the age at first marriage (Suzuki, 2003). Increased standards of living and opportunities for social mobility make one's 20s a time to travel, grow, and seize opportunities for career advancement. In fact, Choe and Retherford (2009) note that single [Korean] women are likely to invest more time in their work in order to improve their chances to return to it after raising children, thus resulting in marriages at even later ages. Given that East Asian women are able to work and lead financially solvent lives, many do not feel the degree of financial pressure they once did to ‘rush into marriage’.

One of the possible effects of the postponement transition in East Asia (i.e., women marrying and concomitantly having children at later ages) is the temporary lowering of the region's TFRs to all-time lows of 1.08 in Korea (2005), 0.9 in Hong Kong (2003), 1.15 in Singapore (2010), 1.26 in Japan (2006), and 0.9 in Taiwan (2010) (World Bank, 2011). While these short- and medium-term trends are similar to those that have been observed in Europe, East Asian countries are distinct in the longer-term magnitude of their fertility declines.

In sharp contrast to Europe, where lowest-low levels of fertility were primarily driven by childbearing postponement (Goldstein et al., 2009) and have risen due to fertility recuperation among older ages (Myrskylä et al., 2012), cohort fertility has fallen dramatically throughout East Asia. As Frejka, Jones, and Sardon (2010, p. 588) state, ‘very few of the postponed births [have been] recuperated’ and as a result, completed cohort fertility rates are ‘as low as, or lower than, the lowest rates in Europe’ (Frejka et al., 2010, p. 602). Frejka et al.'s findings are confirmed by Myrskylä et al.'s (2012) cohort fertility projections which project that the East Asian countries of South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore will experience further declines in completed cohort fertility (below 1.4 for the 1979 birth cohort), and that Japan's CFR will plateau at a very low 1.45.

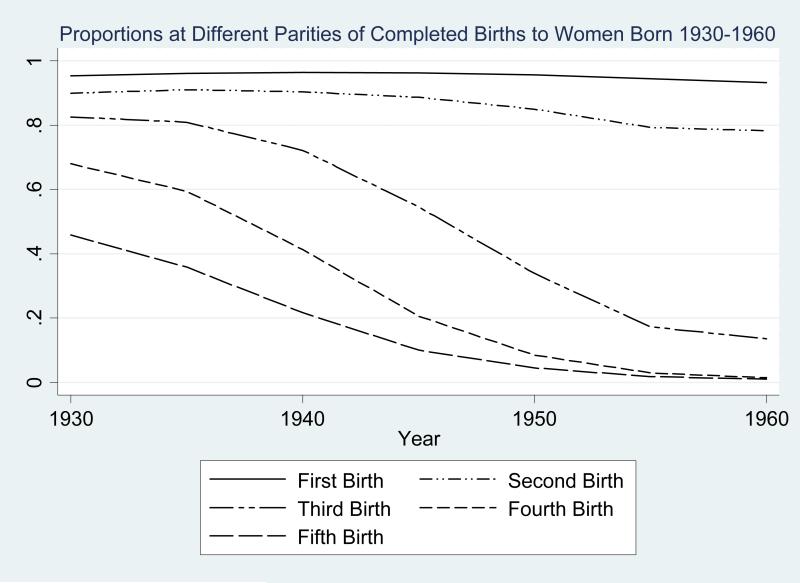

The following Figure 1 dissects the Korean fertility decline by looking at percentages of completed fertility parities for women born from 1930 to 1960. According to the figure, of the women born between 1930–1934 (most of whom entered their childbearing years in the 1950s/1960s), 95.3% had one child or more, while about 90% had two children or more, 83% had three children or more, 68% had four children or more, and 46% had five or more children. When looking at completed fertility of 5 year age cohorts from 1935 to 1960, we note that the percentage of women with at least one child decreased only slightly (from 95% to 93%), while the percentage of families with (at least) two children fell moderately, the percentage of three children families decreased drastically, and families of four children or more fell to nearly zero. Figure 1 thus documents the well-known pattern of stopping behaviour after the first birth as the primary driving force behind the Korean fertility decline in cohorts born during 1930– 1960, rather than an increase in the fraction of women foregoing motherhood (though childlessness has slightly risen during the period). For cohorts born after 1955, there is a clear shift towards single or two-child families, in sharp contrast to cohorts born around 1930 that had fairly high fertility.

Figure 1.

Proportions at Different Parities of Completed Births to Women Born 1930–1960

In this paper we seek to explain why East Asia, the region at the lowest end of the fertility spectrum, has experienced such dramatic and continual declines in fertility. We first discuss how East Asian family structures and gender norms have impacted the region's fertility transition. We then turn to a crucial piece of the East Asian fertility puzzle: education fever. Education fever, and by extension, ‘competitiveness fever’ and ‘English fever’, refers to the high parental investment in education by East Asian parents. In such ultra-competitive, status-driven societies, the cost of raising children in many East Asian countries has become so high that many couples are turning to single or two-child families.

Our analyses, data, and the majority of our discussion focus on South Korea (‘Korea’, hereinafter) as a case study for East Asia. We concentrate on Korea because (1) Korea has experienced the greatest fertility decline over the last five decades among OECD countries; (2) Korea has the highest participation rates of private education in the region, making it an exemplary case to study the relationship between low fertility and private education expenditures 2 ; and (3) the government-collected data on private education expenditures in Korea is the most extensive in the region. Nonetheless, most of the topics covered in this paper (such as familial structures and the relationship between private education and low fertility) are widespread throughout East Asia. Private places of learning similar to the Korean hagwon, for example, are frequented by the majority of children in Japan and Taiwan (where they are known as ‘jukus’ and ‘buxibans’, respectively), and by a sizeable fraction of children in China, Hong Kong, and Singapore. While this paper uses Korea as a case study for the region, it should be kept in mind that the link between having successful offspring (achieved through high investment in education) and low fertility in East Asia is widely recognised as a broad regional phenomenon in which various countries share important commonalities (discussed in more detail below).

Fertility and Family Structures in Developed Countries

While Europe and East Asia can broadly be grouped together for having below-replacement fertility, over the last few decades, we have witnessed a clear divide emerge among below-replacement countries, separating them into countries with moderately-low fertility (TFR of 1.7 to 2.1), low fertility (1.3–1.7) and lowest-low fertility (under 1.3) 3. Moderately low fertility countries are primarily concentrated in Northern and Western Europe while low and lowest-low fertility countries are found in Southern and Eastern Europe and East Asia. Moreover, as it has been pointed out by other scholars, lowest-low fertility has almost exclusively moved to Asia, with no lowest-low fertility country remaining in Europe (with the exception of Moldova) as of 2008 (Goldstein et al., 2009).

While the intent of this paper is not to give a cross-country comparison on low-fertility determinants, it is important to evince that many social dynamics and cultural norms with regard to the family and gender equality in South Korea (and East Asia) parallel those of Southern Europe and differ from those of Northern and Western Europe. Specifically, scholars have pointed to a dichotomy of family structure within the developed world over the last century: strong familism and weak familism. This dichotomy is closely related to fertility levels, as countries with ‘strong familism’ almost always have low or lowest-low fertility while countries with ‘weak familism’ typically have moderately low to stable fertility. Table 1 contains noteworthy characteristics of societies with strong familism and weak familism.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Societies with Weak and Strong Familism

| Strong Familism | Weak Familism |

|---|---|

| • Late parental home move out (“late nest leaving”) | • Premarital parental home move out (“early nest leaving”) |

| • Traditional gender roles | • High degree of individual autonomy |

| • Strong family ties | • Lowered parental authority |

| • Very low out of wedlock births | • Cohabitation common |

| • Cohabitation not very common | • High use of childcare, babysitters, and nannies |

| • Often linked to religion, ideology, or ethical and philosophical system (e.g. Confucianism, Catholicism) | • Housework is shared relatively equally by both men and women |

| • Mothers as primary caregivers | • Moderately low or near replacement level (TFR of 1.7-2.1) common |

| • Women take on household responsibilities | • Northern and Western Europe |

| • Low (TFR of 1.3-1.7) or lowest-low (TFR of or below 1.3) fertility levels common | |

| • Southern Europe, East Asia, Eastern Europe |

(Source: Reher, 1998; Suzuki, 2008)

Societies with strong and weak familism are largely shaped by their defining characteristics. As we later discuss, the feature of weak familism fosters a progressive and egalitarian household environment that comfortably aligns with economic development and social modernisation. This nurtures a childbearing-friendly society and provides a partial explanation for why fertility is relatively high in countries with weak familism. In countries with strong familism, economic development and social modernisation clash with traditionalism in the household. This clash creates an environment in which women face obstacles in balancing home and work life.

Women with children in countries with strong familism are almost always tasked with being the primary caregivers, in charge of managing ‘unpaid work’ or household tasks, and in many cases, expected to work. Balancing a job, a family, and daily household chores is both physically and mentally taxing on women, and makes the prospects of having a large family (three or more children) difficult. Furthermore, career-oriented, individualistic women in countries with strong familism may perceive marriage and childbearing as threatening, as they can interfere with women's self-aspirations or goals. As a result, women in societies with strong familism often delay marriage and childbearing until later ages and in some cases, forego the two entirely.

Societies with weak familism, on the other hand, tend to foster environments in which the mother and father can lead both domestic and professional lives. Government-subsidised day-care and the hiring of babysitters and nannies are highly prevalent in societies with weak familism. These ‘outside care’ sources take much of the burden off mothers to act as the ‘primary caregiver’ and facilitate women in balancing their roles as both workers and mothers. Additionally, the amount of household chores (‘unpaid work’) is much more evenly split between men and women in societies with weak familism than in those with strong familism, thus creating a less taxing situation for mothers.

Lastly, social norms regarding the institution of marriage vary in countries with weak familism and strong familism. In the former, marriage still remains a strong institution but is more of a formality or legal contract as opposed to a religious or social pathway ‘permitting’ one to cohabit and have children. As a result, cohabitation is quite normal and out-of-wedlock births comprise a significant share (if not majority) of total births. In societies with strong familism, conservative social norms dictate marriage as being an important step before cohabiting or childbearing. This explains why countries with strong familism have significantly lower levels of cohabitation and even lower levels of out-of-wedlock births.

A growing body of literature supports the idea that in developed countries, a high level of gender equality is essential in fostering a child friendly society. Myrskylä et al. (2011, p. 4), for example, argue that very low fertility is most prevalent in countries ‘high in health, income and education but low in gender equality’. Their argument appropriately fits within the framework of strong and weak familism, as a society with the former is characterised by a low degree of gender equality and very low fertility and a society with the latter tends to have high gender equality and relatively high fertility.

In Table 2, four countries with strong familism (e.g. South Korea, Japan, Italy, and Spain)4 are compared with four countries with weak familism (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) using key characteristics.

Table 2.

Key Characteristics of Strong and Weak Familism in Selected Countries

| Country | TFR 2009 | % Living at Home: Ages 15-29 | Unpaid Work Difference | % Enrollment Rate: Out-of-school Child Care | Global Gender Gap Index 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 1.94 | 22.2 | 72 | 84.2 | 4 |

| Norway | 1.98 | 27.6 | 73 | 71 | 2 |

| Denmark | 1.84 | 23.9 | 57 | 87.8 | 7 |

| Finland | 1.86 | 15.5 | 91 | 26 | 3 |

| Italy | 1.41 | 73.2 | 223 | 3.8 | 74 |

| Spain | 1.4 | 64.2 | 187 | 7.4 | 11 |

| Japan | 1.37 | 66.5 | 210 | 11.2 | 94 |

| South Korea | 1.27 | 68 | 182 | 2.6 | 104 |

The ‘percentage of 15-29 year olds living at home’ illustrates that nest leaving occurs later in societies with strong familism and earlier in others. The difference in unpaid work indicates how many more minutes women spend a day doing household chores than men. The enrollment percentage of “out-of-school” childcare refers to the use of non-parental childcare, and sheds light on the high use of outside source childcare in weak familism countries and the low use of outside source childcare in strong familism countries. The data were nationally collected and compiled by the OECD, though the age ranges corresponding to each country vary slightly (6-10 years old in Italy, 6-8 in Korea, 6-11 in Japan, 3-5 in Spain, 7-9 in Finland, 6-8 in Denmark and Sweden, and 3-10 in Norway). Lastly, the Global Gender Gap Index, a measure of gender inequality, indicates the “rank” of each country (out of 192 countries, 1 being the most gender equal country and 192 being the least). The fertility rate of each country is included to stress that weak familism countries have much higher fertility than strong familism countries.

Sources:

TFR: World Bank (2011).

% Living at Home: European and World Values Survey, 1999 (Denmark), 2005 (Italy, Japan, South Korea, Finland), 2006 (Sweden), 2007 (Spain and Norway).

Unpaid Work Difference: OECD, 2010.

% Enrollment rate: Out-of-school childcare: OECD, 2011a, OECD, 2011b; Global Gender Gap Index: Hausmann, Tyson, & Zahidi, 2010.

Like other countries with strong familism, Korea also has very conservative traditions with regard to household and gender roles. The country has experienced economic prosperity over the last fifty years, but despite the technological, economic, and social advances, Korea still harbours high gender inequality and long-established social norms. As highlighted, based on the recent theories and empirical evidence that points to gender equality as an important factor facilitating moderately low, rather than very low or lowest-low fertility in developed societies (Myrskylä et al., 2011; McDonald, 2002), this ‘clash’ between economic development/social modernisation and household traditionalism foments a society almost destined to persistently have very low fertility rates.

Korean mothers primarily hold the responsibility for raising their children. This deeply rooted norm, coupled with a lack of public childcare facilities and high childcare costs, makes it difficult for the average woman to evade this societal expectation. Additionally, Korean women assume responsibility for the majority of rudimentary household tasks from cooking to cleaning (Jones, 2011). After the 1997 financial crisis, Korean men who once insisted on being the sole breadwinner came to realise the financial advantage of a working wife and began to favour employed women when searching for a wife (Eun, 2007). This not only made it more socially acceptable for women to work but also encouraged them to do so. Now, women who decide to marry and have children often find it physically and mentally strenuous to raise multiple children while also having to manage the majority of household chores and in many cases, work a job (see Caldwell & Caldwell, 2005). The obstacle faced by mothers to balance their work and home lives—stemming mainly from high gender inequality—exerts an immeasurable yet undoubtedly important influence on Korea's low fertility rate.

Familial traditionalism and gender inequality are not particular to Korea but can also be found in other highly economically and technologically advanced countries. Many Southern and Eastern European countries, along with most East Asian countries, enjoy highly modernised economies but still manifest strong familism. Women in these regions are faced with the same difficulties as women in Korea, namely that of balancing a job and childcare. Yet, while fertility in Southern and Eastern Europe is very low, both period and cohort fertility seemed to have stopped falling in these regions (Myrskylä et al., 2012) and have never reached the lowest points as experienced in East Asia. Why is fertility saliently lower in East Asia than in Southern and Eastern Europe, where fertility levels have recently risen above the ‘lowest-low’ TFR threshold of 1.3?

The title of this article refers to East Asian fertility as a ‘puzzle’ because the literature on the topic lacks a thorough and compelling explanation for why East Asian families have experienced continual declines in family size. Popular media and various academic sources speculatively point to the high cost of raising children as driving low fertility, but none has been able to provide a convincing case for their suspicions, and careful empirical analyses are scarce. The remainder of this paper draws upon recently published quantitative and qualitative data to add credibility to the argument that the high costs invested in one's offspring, specifically in their education, partially explain why East Asian fertility persists at such a low level. As stated, most of our analyses and discussion are centred on Korea, though these driving factors of low fertility and more generally, the notion of ‘quality over quantity’ regarding family size, is similarly pervasive throughout East Asia.

The Missing Piece to the Korean Fertility Puzzle: Education Fever, English Fever, and Competitiveness Fever

Obsession with education in Korea has become an integral part of contemporary Korean culture and affects all aspects of social life. Deeply rooted Confucian values stress education as the best way for achieving high social status and economic prosperity (Seth, 2002). Park (2009) argues that more recently, a collapse of the hierarchical social class system coupled with egalitarian ideas from the West have created the notion that any Korean child can achieve personal advancement, economic prosperity, and social mobility through education. Korean parents widely recognise this and see it as their duty to provide their children with the proper educational resources and support in order to produce successful and competitive children. In the mid-1970s as part of their family planning project, even the Korean government adopted the notion of ‘quality over quantity’ with colourful and creative ‘population propaganda’ exclaiming: ‘Daughter or son, let's not think about which. Just have two and raise them well’ (J. Lee, 2009).

The 1997 economic crisis in Korea is commonly noted for intensifying Korea's competitive environment (see, for example, Eun, 2007; Park, 2009). During this time, according to Eun (2007, p. 7), ‘[job] uncertainty was endemic’ and standing out as more qualified than others was an absolute necessity in order to receive the best university education and later obtain a well-paid and secure job.

Once illegal for allegedly ‘promoting social inequality’, hagwons, also known as ‘cram schools’ or ‘private after-school education centres’, were once again permitted by the Korean government in the 1990s and have been exploding in popularity ever since. Students attend hagwons after their regular school hours for additional training in all subjects including math, writing, music, science, and perhaps the most common, English. Hagwons are seen by many as crucial for admission to Korea's utmost prestigious and elite ‘SKY’ universities (Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University). Sending one's child to after-school activities has become embedded in the Korean culture as a social norm. In fact, over 75% of children in 2009 partook in some form of private education (Korea National Statistical Office [KNSO], 2009). Parents who fail to send their children to these additional lessons, i.e. breaking the norm, may even run the risk of being classified as irresponsible or even neglectful parents (Lee, 2011).

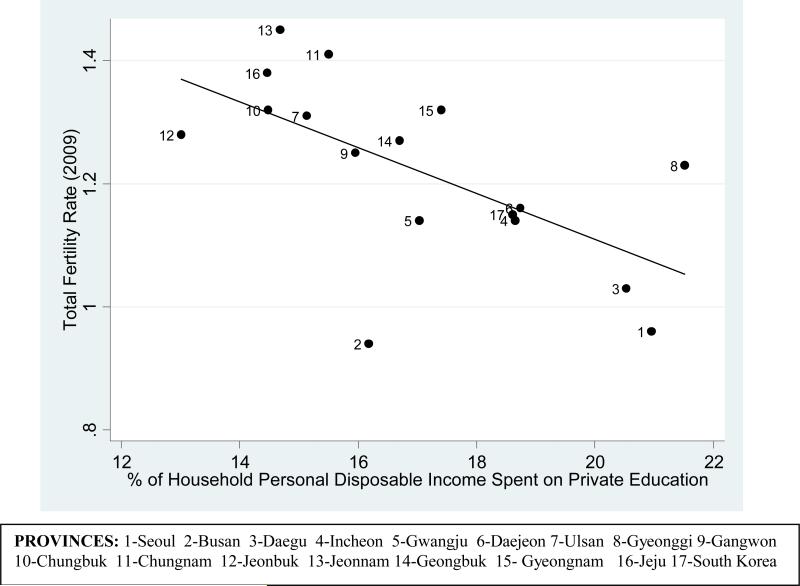

Hagwons are notoriously expensive and as a result, they are often cited by parents in popular media as a reason why they only have only one or two children (see ‘Qualitative Support’ below). The social pressure to send one's child or children to hagwons coupled with the high cost of private education is likely to deter the idea of a big family. After all, the more children in a family, the fewer financial resources are able to be delegated to each child's education and, as thought by many Korean parents, the less likely their children will end up being ‘successful’. In an attempt to measure the effect of private education expenditures on fertility behaviour, we correlate provincial average income adjusted education expenditures with the respective regional total fertility rates for the year 2009.

First, we use data from the 2009 Survey of Private Education Expenditure (KNSO, 2009) which reports yearly expenditures on private education for the entire country of Korea and each of its 16 provinces. While the average amount spent on monthly private education expenditures equated to 240,000 won (US$208) per student in 2009, there was great provincial variation in the amount spent, from 160,000 won (US$140) per student in Jeonbuk to 321,000 won (US$278) in Seoul. The 2009 report on ‘Regional Income Estimation’ from Statistics Korea reports the personal disposable income (PDI) for Korea as a whole as well as for each of the 16 provinces. The data also shows great variability among the different provinces, as the average family in Seoul had nearly 15,800,000 won (US$13,700) while the average family's personal disposable income in Jeonnam was just 11,104,000 won (US$9,600). In order to account for provincial income differences, we divide the average monthly private education expenditure by the personal disposable income for each of the 16 Korean provinces and the country as a whole, thus yielding the percentage of personal disposable income spent on private education.

There are various reasons why we focus on a provincial analysis to explain the effects of private education expenditures on fertility as opposed to examining the relationship on a cross-country analysis. First, Korea is largely homogeneous which makes widely differing cultural or societal norms across different provinces unlikely. Second, competition to enter university is countrywide; it is equally difficult for all students to be accepted into university and therefore private education to enhance competitiveness is ‘equally necessary’ across all provinces. Third, the tax structure and governmental investment in education is uniform for Korea; the risk of inaccurately comparing public and private investments in education in proportion to tax structure and income differences across multiple countries would be relatively high.

We perform a linear regression analysis using the total fertility rate of each province, provided by Statistics Korea upon request, and the provincial percent of income spent on private education. The scatter plot with the regression coefficient is found below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Personal Disposable Income Spent on Private Education and Provincial Total Fertility Rates

The regression scatter plot (Figure 2) suggests that after income adjustment, regions in which parents spend more on education tend to have fewer children than regions where parents spend less on their children's education. This relationship strengthens our hypothesis that there exists a relationship between private education expenditures and fertility, where an increase in the former is associated with a decrease in the latter.5

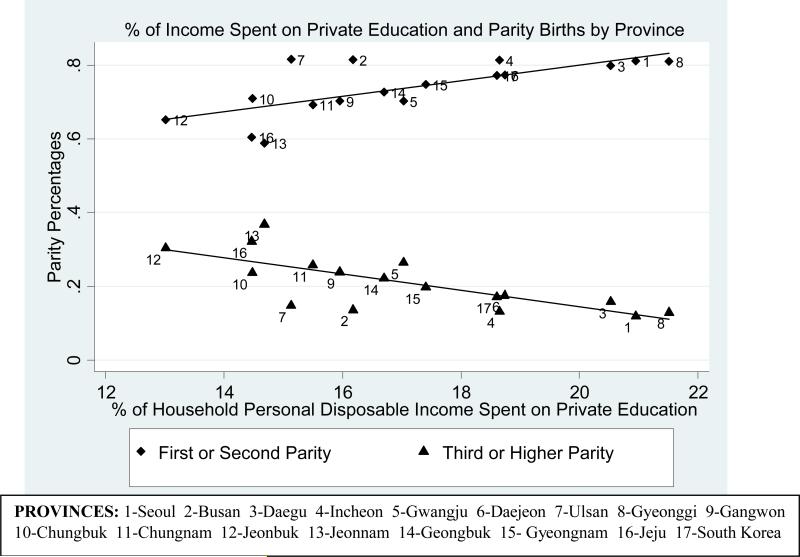

Next, in an attempt to examine the relationship between family size and education expenditures, we correlate parity percentages (i.e. the percentage of women with one, two three, etc. children) with income adjusted private education expenditures by province. For this purpose, we gathered data from the 2005 Korean census and calculate the percent parities of women aged 45–49 years in each of the Korean provinces used in Figure 4.6 Since the hypothesis is that ‘private education expenditures make it financially difficult for families to have more than a couple children’, we group the first and second parity percentages and the third, fourth and fifth parity percentages to form two aggregate statistical groups.7 We then correlate the provincial income adjusted private education expenditures with the two groups of parity percentages (‘first and second’ and ‘third or higher’). The results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Percentage of Personal Disposable Income Spent on Private Education Expenditures and Percent Parity Groups of Women aged 45-49 by Province

Furthermore, Figure 3 supports our hypothesis that private education expenditures discourage couples from having families with more than two children. From the figure, we note that families in provinces with a greater concentration of small families (one or two children) spend, on average, more of their PDI on their children's education while families in provinces with a greater concentration of large families (three or more children) spend much less of their PDI on their children's education. In other words, regions with higher percentages of families with one or two children correlate positively with higher percentages of PDI spent on private education. Conversely, the concentration of large families correlates negatively with higher average spending on private education.

When examining the scatter plot in Figure 2, the provinces of Gyeonggi (8) and Busan (2) stand out as outliers to the relationship. In the province of Gyeonggi, both the birth rate and the private education expenditure are relatively high (a deviation from our ‘high(er) expenditure, low(er) fertility’ relationship). On the other hand, the province of Busan has extremely low fertility with a relatively low per household payout on private education expenditures. Geographic location and internal migration are two possible factors to explain why Busan and Gyeonggi deviate from the linear relationship.

Gyeonggi sits in the northern part of South Korea and was home to Seoul until 1943 when the nation's capital administratively separated to form a ‘special city’. While Seoul is the country's financial and political hub, it lacks the abundance of space and security needed to create a family-friendly environment. For this reason, there has been a trend for married couples in their ‘prime childbearing years’ (twenties to thirties) to relocate to the suburbs of Seoul (located in Gyeonggi) to start their families while commuting to work in Seoul (KNSO, 2010). In 2010 alone, the province of Gyeonggi ‘gained’ 142,437 people while Seoul ‘lost’ more than 115,000 of its citizens, mostly to Gyeonggi (KNSO, 2010). The influx of married Seoulite couples to Gyeonggi, many of whom probably have children shortly after moving, is a likely reason why fertility is ostensibly higher in Gyeonggi than in Seoul.

Similarly, the southern port city of Busan separated in 1963 from Gyeongnam to become its own ‘distinct administrative entity’ or province. Busan, like Seoul, has a large urban to suburban migration pattern of those in their childbearing years; from 2005 to 2010, over 80,000 of Busan's residents relocated to the ‘suburbs’ in the province of Gyeongnam (KNSO, 2010). The notion that couples in Korea's two largest cities, Seoul and Busan, leave the big cities to have children in the ‘satellite cities’ naturally boosts the fertility rates in their suburbs (Gyeonggi and Gyeongnam, respectively) while having an equal but opposite effect on the fertility rates in the cities.

Qualitative Support

From the quantitative results above, it is evident that there exist statistically significant relationships between (1) private education expenditures and total fertility rates by province and (2) private education expenditures by region and family size. In addition to these relationships, various surveys and interviews strongly reinforce the hypothesis that private education expenditures lower the average Korean couple's proclivity to have more than just one or two children.

J. Lee (2009) quotes a report from the Korea Institute for Health and Social Issues which stated that ‘economic climate is one of the factors that has “especially played a role in people's delaying or giving up on having children”’.

A survey by the Korean National Statistics Office asked householders about the ‘difficulties in educating primary school students’ (KNSO, 2007). More than 77% of the respondents reported the ‘burden of expense in private education and daily life’ as the main difficulty in educating primary school students, followed by 9% who said the main difficulty in educating primary school students was ‘balancing between children and social life’.

The most recent social survey from the Korean National Statistics Office (KNSO, 2011) polled the ‘awareness of child education expenditure burden’ in Korea. The survey revealed that 37.4% of respondents view education expenditures as a ‘heavy burden’, 40% as a ‘substantial burden’, 16.6% as ‘average’ and only 5% as ‘slightly or not a burden’.

Personal accounts in mainstream media along with documented interviews also consistently report that the extreme cost of raising children causes couples to make the conscious decision to stop having more than one or two children. For example, a 2011 article in Channel NewsAsia cites Noo Suh Kyung, a housewife with two children, who says that ‘It's very difficult to raise two children. We thought about a third child but after doing the calculations and realising how much it would cost to raise three children all the way to college, we knew it would be impossible. And so we gave up the idea’ (Lim, 2011). In the same article, Lee Ko Woon, a Korean mother of one, states that ‘I don't think we can have more children. It just costs so much to educate them. The government is offering no incentives and yet it keeps urging people to have more children’ (Lim, 2011).

Lastly, a 2012 survey by the Health Ministry showed that nine out of 10 people in Korea say the country's low fertility rate is ‘serious, but [people] are reluctant to have children due to financial problems’ (Ji-Sook, 2012). Respondents of the survey said ‘education costs including private education fees was the most burdensome expense’, and as Ji-Sook (2012) explains, they ‘found it hard to balance family and work’.

English Fever and Competitiveness Fever

The phenomena of ‘English fever’ and ‘competitiveness fever’ merit discussion in this paper because they shed further light on the parental fervour to produce successful children. As touched upon earlier, the 1997 Asian financial crisis intensified the competitive environment in Korea (Eun, 2007) and has led parents to take over-the-top measures to ensure their children are competitive and do not have to face the economic hardships they did. The extent to which parents go in their attempts to create successful children has transcended the formal educational realm and is now the root cause of two Korean cultural peculiarities known as the ‘geese father phenomenon’ and ‘competitive parenting’.

To best understand the reasoning behind the ‘geese father phenomenon’, one must understand the importance of the English language in contemporary Korean culture. Speaking English in Korea is not simply a chic status symbol anymore, but a necessary qualification to stand out in the job market. Park (2009) identifies three historical reasons why Koreans see fluency in English as so important: first, the Korean government has instituted a number of policy changes which have placed a greater emphasis on learning English. Among these include the introduction of a listening section to the national college entry examinations and a shift from more ‘grammar-based’ exams to exams based on ‘communicative English’. Second, according to Park (2009, p. 52), the introduction of English ‘in all [Korean] elementary schools’ in 1995 prompted parents to seek out-of-school resources such as ‘English-only private institutions, English learning materials for kids, and English conversation services’. And third, the Seoul Olympic Games and 1997 Korean financial crisis illustrated how important a solid grasp on the English language was in a globalised world. As a result, the ‘English fever’ phenomenon has gripped Korea, causing some people to take unique, almost eccentric steps to ensure their children speak English fluently.

The Korean phenomenon of ‘girogi appa’, or ‘(wild) geese fathers’, refers to a growing number of Korean fathers who send their children and wives to English speaking countries while retaining their jobs in Korea (Eun, 2007). The geese fathers generally visit (or ‘migrate to’) their families on a yearly basis. While no official numbers exist, a recent New York Times article estimates that a staggering 40,000 South Korean schoolchildren live abroad with their mothers while their fathers work in Korea (Onishi, 2008). Geese families reflect the sacrifices made by Korean parents to ensure that their children are multilingual and receive a ‘competitive edge’ through a foreign education, as ‘foreign diplomas are often regarded as superior to a Korean education’ (Eun, 2007, p. 11).

Within Korea, English fever has even led to what some call ‘competitive parenting’. Because Korean parents see their children's success as a reflection of their parental efforts, parents compete amongst themselves to enrol their children in the best hagwons, English language courses, or day-care centres. As Shin Dongpyo states in a televised PBS special on education in Korea, ‘You see your neighbor's kid speak better English than your kid, and you try to figure out what kind of English program he is getting and what kind of kindergarten he is attending. You have figured it out, and you send your kid to same kindergarten—that kind of competition going on’ (PBS, 2011). Competitive parenting itself illustrates the broad cultural notion that parents can take certain measures to ensure their offspring attain high social and economic status.

Education Fever and in Other Parts of East Asia

Though the following surveys and data are not standardised and therefore cross-country enrolment rates cannot be compared, they provide credence to the claim that education fever is indeed ubiquitous throughout East Asia: in Hong Kong, surveys conducted in 2009 indicate that about 72.5% of primary students and 85% of secondary students received some form of private tutoring (Ngai & Cheung, 2010; Caritas, 2010). An education panel survey in Taipei (Taiwan) found that approximately 73% of grade seven students were receiving about 6.5 hours per week of private tutoring (Liu, 2012). Although official statistics in Singapore do not exist, Tan (2009) notes that the ‘phenomenon has been prevalent in Singapore for decades’—a statement which is corroborated by a 2008 newspaper poll which found that 97% of students were receiving some kind of private tutoring (Toh, 2008; Bray & Lykins, 2012). While in Japan, a survey found that 65.2% of junior secondary three students attended juku (Japanese cram schools) in 2007 (Ministry of Education and Training, 2008, p. 13).

Like education fever, English fever is endemic throughout East Asia (Krashen, 2006). ‘In Taiwan and elsewhere’, writes Witten-Davies (2006, p. 2), ‘[people] have been starting English earlier, sending children to extra classes (‘cram schools’), hiring tutors and studying abroad’. Liu (2002) calls studying English a ‘national obsession’ in Taiwan, while Chang (2003) notes the eagerness of parents to sign their kids up for English classes in kindergarten or grade one. In Hong Kong, English is presumed to be in greatest demand because it is ‘not only [important] as a subject but also as a medium of instruction for other subjects’ (Bray & Kwock, 2003, p. 614). While cram schools in Japan do teach English, the Japanese are not as fervent about learning English as their East Asian counterparts.

Though these two trends are widespread within East Asia, Takayasu (2003, 2005) argues that there is significant variation in the intensity of education obsession throughout the region. Behind this variation lie cultural, demographic, and economic factors.

Many isolated cultural elements make education fever ‘hotter’ in some Asian countries. In Korea's case, many scholars consider Korea as the ‘most Confucius’ country in East Asia (Berthrong & Berthrong, 2002), so it should come as little surprise that one of the pillars of Confucianism, education, is likewise strongest in Korea. For Japan, the notoriously independent-minded attitude of the Japanese toward the rest of the world may explain why they are less fanatical about learning English (Beck & Dujarric, 2010; Park, 2009). Differences in living standards between individuals with different educational attainment levels are more pronounced in some societies, particularly in Hong Kong and Singapore, making the ‘rewards from extra levels of schooling, and from supplementary tutoring...greater in some Asian societies’ (Bray, 1999, p. 30).

Second, as Takayasu (2003) suggests, demography may help explain why Japan's case of education fever has ‘cooled down’ over the last decade and a half in comparison with other countries in the region. Japan's fertility rate has been below-replacement over a long period of time (since 1974), which invariably translates into smaller birth cohorts and reduced competition for university spots. Compared to Japan, fertility rates (and sizes of birth cohorts) declined more recently in other East Asian countries, the educational environment remains very competitive, and demand for additional private, out-of-school tutoring remains strikingly high.

Lastly, related to Dore's hypothesis (1976) that late development is linked with a greater societal emphasis on education, the ‘compressed’ development stories of the Asian Tigers differ from that of Japan, which, while also considered a ‘latecomer to industrialization’, was an ‘economic superpower long before South Korea’ (Takayasu, 2003, p. 204). In the ‘Tiger countries’ (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Korea), intergenerational experiences regarding wealth and opportunities have been starkly different for the pre-development (before 1960s), in-transition (1960s–1980s), and post-development (1990s–present) generations. The oldest generation (‘the grandparents’ of today) grew up in an impoverished environment lacking economic opportunity and social mobility; the sandwich generation (‘the parents’) were born into a world of social and economic transition in which the value of education became an overtly important requisite for success in a country with more people than well-paid jobs; and today's children and teens have inherited their parents’ (the ‘sandwich’ generation's) education fever mentality. Interestingly, similar patterns are occurring in Eastern Europe, where the fall of socialism and the subsequent prospect of greater and faster social mobility have led to a ‘rapidly-spreading’ phenomenon of private tutoring (Silova, 2010).

As we have highlighted with regard to Myrskylä et al.'s (2012) cohort fertility projections, a unique feature regarding fertility in Japan is its expected plateauing, as opposed to further (expected) declines in fertility in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. Explaining these trends in fertility behaviour may be a result of these cultural, demographic and economic factors. Less intense education fever due to a lesser emphasis on Confucian values, smaller birth cohorts and less competition, and weaker intergenerational differences in wealth may explain why parents in Japan are less zealous about producing ultra-competitive kids. This comparatively lower level of competition may explain why family size is not expected to shrink further in Japan.

Discussion and Conclusions

High household gender inequality prevalent in Korea (and East Asia) discourages educated, career-oriented and independent females from seeking marriage. Women who do decide to marry often find themselves carrying a ‘double burden’ of working and managing the majority of household tasks (or ‘unpaid work’), making the prospects of a large family both stressful and unmanageable (Kim, 2005). These difficulties are faced by women in Southern European societies with strong familism where fertility is also very low, but not as low as Korean fertility.

Because Korean parents take a larger responsibility in their offspring's future success compared to Western parents, the notion of ‘quality over quantity’ is presumably more pervasive and influential in determining family size in the country. Given the high social pressure felt by parents to invest large amounts of time and money in their child(ren)'s education, Korean parents often find it difficult and discouraging to have more than one or two children, despite the fact that desired family size for young adults has hovered around two for the last three decades (Jun, 2005; Nishimura, 2012). Thus, what separates Korea from low-fertility countries in the West, similar in economic development and familial structure, is the steadfast parental drive to produce super-educated, competitive children. In such a competitive country, the average Korean parents are often willing to forego their ideal family size for fewer children so that they can maximise their children's success later in life.

The constant pressure felt by Korean parents to ensure their children lead successful lives drives parents to spend large amounts of time and money on their offspring. Korean parents simply wish the best for their children's futures; the measures they take to produce competitive children, now both within and outside of the academic realm, are intended to put their children on a successful path.

What will the future hold for fertility in Korea? Above all, one must bear in mind that the reduction in the pace of postponement could increase fertility rates slightly by reducing tempo effects. Additionally, new governmental provisions to create a child-friendly environment will likely raise the fertility rate if the measures are successful in making it easier for women to balance a work and home life.

Yet, as the ‘competition’ for university spots is only relative and the labour market is inelastic, high test scores or the ability to speak English mean little if everyone else has similar qualifications.8 It is this principle which has driven and will continue to drive parents to participate in over-the-top practices to ensure that their children will outperform, outscore, and out-qualify the rest.

Further research is likely to confirm our presumption that the relationship between low fertility and expenditures on private education is applicable to other countries in the region, as parents in many other East Asian countries anecdotally stress ‘quality over quantity’ more than Western parents, place very high importance on education in their children's lives, and take measures similar to those that Koreans take to ensure that their children are successful and competitive. If the notion of child quality over quantity is indeed more intense in East Asia than the rest of the developed world, are East Asian countries destined to persistently have the world's lowest fertility rates? 9

Acknowledgements

This research received support from the Population Research Training Grant (NIH T32 HD007242) awarded to the Population Studies Center at the University of Pennsylvania by the National Institutes of Health's (NIH)'s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.” The PI is Hans-Peter Kohler.

Footnotes

Fertility across most of Europe has declined slightly since the onset of the recession. A careful analysis by Sobotka, Skirbekk, and Philipov (2011), however, suggests that these declines are likely to have been caused primarily by childbearing postponement as opposed to quantum changes.

In fact, a 2011 Time Magazine article titled ‘Teacher, leave those kids alone’ even mentions that compared to other parts of Asia, Koreans have taken education to “new extremes” (Ripley, 2011). The article also quotes the Singaporean Education Minister, who when asked about Singapore's reliance on private education last year, responded optimistically that ‘We’re not as bad as the Koreans’ (Ripley, 2011).

We use the UN definition of East Asia: China, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

We use these four countries with strong familism because they represent the two regions where strong familism is most prevalent, East Asia and Southern Europe.

It is generally recognised that high housing costs in Korea are a large financial drain on families, though we found no significant correlation between housing costs (as measured by a 2009 Housing Price Index) and regional TFRs.

It can be said with much certainty that the females in the studied age cohort (45–49) have completed childbearing.

As so few families have more than five children, it is statistically insignificant to use above the fifth parity percent.

Indeed, Korean students have achieved very high test scores. In fact, Korean ‘education fever’ has given the country the top spot on the PISA Education literacy comparison (OECD, 2011a).

This paper does not examine the possibility of the Easterlin effect on the future of South Korean fertility. Pampel and Peters (1995, abstract) concisely define the Easterlin effect as ‘cyclical changes in demographic and social behavior as the result of fluctuations in birth rates and cohort size during the post-World War II period’. The Easterlin effect argues that as cohort sizes fluctuate, so do family structures, income, career and education competition, and fertility rates (Easterlin, 1973; Waldorf & Franklin, 2002; Pampel & Peters, 1995). The “effect” has received both praise and criticism and is said to be “mixed at best and plain wrong at worst” (Pampel & Peters, 1995). If the Easterlin effect were to apply to Korea, the country would likely experience cyclical periods of high and low fertility and thus the current period of lowest-low fertility would simply be an ephemeral phase. Further research is needed to examine if smaller future cohort sizes will indeed loosen competition in both the academic and labour realms. Furthermore, if smaller cohorts have higher income, will the burden of educational expenditures be as high as it currently is? And lastly, will social norms change to foster greater gender equality, a less traditional family structure, and a more child-friendly environment? Such possibilities would surely have consequences on the country's fertility rate.

Contributor Information

Thomas Anderson, Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. andt@sas.upenn.edu.

Hans-Peter Kohler, Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA..

References

- Beck P, Dujarric R. Why can't Japan be more like South Korea. [August 16, 2012];The Japan Times. 2010 Nov 4; from http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/eo20101104a2.html.

- Berthrong JH, Berthrong EN. Confucianism: A short introduction. Oneworld; Oxford: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bray M. The shadow education system: Private tutoring and its implications for planners. Fundamentals of Educational Planning 61, Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) 1999 Available on-line: http://www.iiep.unesco.org/information-services/publications/search-iiep-publications/economics-of-education.html.

- Bray M. Adverse effects of private supplementary tutoring: Dimensions, implications and government responses. Series “Ethics and Corruption.” Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP) 2003 Available online: http://www.iiep.unesco.org/information-services/publications/abstracts/2003/etico-adverse-effects.html.

- Bray M, Kwok P. Demand for private supplementary tutoring: conceptual considerations, and socio-economic patterns in Hong Kong. Economics of Education Review. 2003;22(6):611–620. [Google Scholar]

- Bray M, Lykins C. Shadow education: Private supplementary tutoring and its implications for policy makers in Asia. Asian Development Bank; N.p.: 2012. Mapping the landscape. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Caldwell BK. The causes of the Asian fertility decline: Macro and micro approaches. Asian Population Studies. 2005;1(1):31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Caritas, Community and Higher Education Service . Private supplementary tutoring of secondary students: Investigation report. Caritas; Hong Kong: 2010. Retrieved from http://klncc.caritas.org.hk/private/document/644.pdf. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y-P. Students should begin English in grade three. Taipei Times; Mar 17, 2003. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Choe MK, Retherford RD. The contribution of education to South Korea's fertility decline to “lowest-low” level. Asian Population Studies. 2009;5(3):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dore RP. The diploma disease. George Allen & Unwin; London: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Relative economic status and the American fertility swing. In: Sheldon EH, editor. Family economic behavior: Problems and prospects. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1973. pp. 170–223. [Google Scholar]

- Eun K-S. Lowest-low fertility in the Republic of Korea: Causes, consequences and policy responses. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2007;22(2):51–72. [Google Scholar]

- European and World Values Surveys four-wave integrated data file, 1981–2004, v.20060423, 2006. Surveys designed and executed by the European Values Study Group and World Values Survey Association. File Producers: ASEP/JDS, Madrid, Spain and Tilburg University, Tilburg, the Netherlands. File Distributors: ASEP/JDS and GESIS, Cologne, Germany.

- Frejka T, Jones GW, Sardon J-P. East Asian childbearing patterns and policy developments. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(3):579–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JR, Sobotka T, Jasilioniene A. The end of ‘lowest-low’ fertility? Population and Development Review. 2009;35(4):663–699. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann R, Tyson LD, Zahidi S. The global gender gap report. World Economic Forum; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ji-Sook B. Low birthrate serious, education costs to blame. The Korea Herald. Retrieved May. 2012 Jan 17;26:2012. from http://view.koreaherald.com/kh/view.php?ud=20120117001010&cpv=0. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; New York: 2011. Recent fertility trends, policy responses and fertility prospects in low fertility countries of East and Southeast Asia. Expert paper no. 2011/5 Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/expertpapers/2011-5_Jones_ExpertPaper_FINAL_ALL-Pages.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jun K-H. The transition to sub-replacement fertility in South Korea: Implications and prospects for population policy. The Japanese Journal of Population. 2005;3(1):26–57. Retrieved from http://www.ipss.go.jp/webjad/webjournal.files/population/2005_6/jun.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D-S. Theoretical explanations of rapid fertility decline in Korea. The Japanese Journal of Population. 2005;3(1):2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, Billari FC, Ortega JA. Low fertility in Europe: Causes, implications and policy options. In: Harris FR, editor. The baby bust: Who will do the work? Who will pay the taxes. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; Lanham, MD: 2006. pp. 48–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, Billari FC, Ortega JA. The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review. 2002;28(4):641–680. [Google Scholar]

- Korea National Statistical Office (KNSO Korean Census. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- KNSO Birth Statistics. 2004 Retrieved from http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/index.action.

- KNSO Korean Census. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- KNSO Report on the Social Statistics Survey. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- KNSO Birth Statistics. 2004 Retrieved from http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/index.action.

- KNSO Korean Census. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- KNSO Survey of Private Education Expenditures. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.kosis.kr/index.html.

- KNSO Report on internal migration. 2010 http://kostat.go.kr/portal/english/surveyOutlines/1/5/index.static.

- KNSO . Report on the Social Statistics Survey. Korea National Statistics Office; 2011. p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krashen S. English fever. Taipei: Crane Publishing Company. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Where children are “too expensive”. Global Post. 2009 Jan 24; http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/south-korea/090112/where-children-are-too-expensive.

- Lee SK. Local perspectives of Korean shadow education. [May 25, 2012];Reconsidering Development. 2011 2(1):31–52. from http://journal.ipidumn.org/node/148. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Does cram schooling matter? Who goes to cram schools?. International Journal of Educational Development. 2012;32(1):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Studying English a national obsession. [May 24, 2012];Taiwan Today. 2002 Dec 20; from http://taiwantoday.tw/ct.asp?xItem=19773.

- McDonald P. Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review. 2002;26(3):427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education and Training, Japan . Report on the situation of academic learning activities of children. Monbukagakusho Hokokusho; Tokyo: 2008. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- Myrskylä M, Kohler H-P, Billari FC. Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature. 2009;460(7256):741–743. doi: 10.1038/nature08230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrskylä M, Kohler H-P, Billari FC. Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania; 2011. High development and fertility: Fertility at older reproductive ages and gender equality explain the positive link. Working Paper PSC 11-06 Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/psc_working_papers/30. [Google Scholar]

- Myrskylä M, Goldstein JR, Cheng Y-HA. New cohort fertility forecasts for the developed world. 2012 MPIDR Working Paper 2012-014. Retrieved from http://www.demogr.mpg.de/papers/working/wp-2012-014.pdf.

- Ngai A, Cheung S. Youth Poll Series No. 188. Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups; Hong Kong: 2010. Students’ participation in private tuition. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T. Discussion Paper Series. Kwansei Gakuin University; 2012. What are the factors of the gap between desired and actual fertility? A comparative study of four developed countries. Retrieved from http://192.218.163.163/RePEc/pdf/kgdp81.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (OECD) Society at a Glance 2011 - OECD Social Indicators. 2011a Retrieved from www.oecd.org/els/social/indicators/SAG.

- OECD Out-of-school-hours and care services. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/familiesandchildren/42063425.pdf.

- Onishi N. For English studies, Koreans say goodbye to dad. New York Times; Jun 8, 2008. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC, Peters EH. The Easterlin effect. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21(1):163–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.21.080195.001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J-K. ‘English fever’ in South Korea: Its history and symptoms. English Today. 2009;25(1):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) In hypercompetitive South Korea, pressures mount on young pupils. PBS; Jan 21, 2011. [May 24, 2012]. from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/education/jan-june11/koreaschools_01-21.html. [Google Scholar]

- Reher DS. Family ties in Western Europe: Persistent contrasts. Population and Development Review. 1998;24(2):203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley A. Teacher, leave those kids alone. Time Magazine; Sep 25, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2094427,00.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth MS. Education fever: Society, politics, and the pursuit of schooling in South Korea. University of Hawaii Press; Honolulu: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Silova I. Private tutoring in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Policy choices and implications. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 2010;40(3):327–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T, Skirbekk V, Philipov D. Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(2):267–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YS. Rising cost of education depresses S.Korea's birth rate. [July 24, 2011];Channel NewsAsia. 2011 Feb 7; from http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/eastasia/view/1109234/1/.html.

- Suzuki T. Lowest-low fertility in Korea and Japan. Jinko Mondai Kenkyu (Journal of Population Problems) 2003;59(3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T. Korea's strong familism and lowest-low fertility. International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 2008;17(1):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu N. Educational aspirations and the warming-up/cooling-down process: A comparative study between Japan and South Korea. Social Science Japan Journal. 2003;6(2):199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu N. Educational system and parental education fever in contemporary Japan: Comparison with the case of South Korea. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy. 2005;2(1):35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. Private tutoring in Singapore: Bursting out of the shadows. Journal of Youth Studies (Hong Kong) 2009;12(1):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Toh M. Tuition nation. [August 20, 2011];Asiaone News. 2008 from http://www.asiaone.com/News/Education/Story/A1Story20080616-71121.html.

- United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Population Estimates and Projections Section. 2011 Retrieved from http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

- Waldorf B, Franklin R. Spatial dimensions of the Easterlin hypothesis: Fertility variations in Italy. Journal of Regional Science. 2002;42(3):549–578. [Google Scholar]

- Witton-Davies G. What does it take to acquire English? The International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching. 2006;2(2):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Development Indictors. ESDS International, University of Manchester; Apr, 2011. 2011. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5257/wb/wdi/2011-04. [Google Scholar]