Abstract

Duplication of theTBK1 gene causes normal tension glaucoma (NTG); however the mechanism by which this copy number variation leads to retinal ganglion cell death is poorly understood. The ability to use skin-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to investigate the function or dysfunction of a mutant gene product in inaccessible tissues such as the retina now provides us with the ability to interrogate disease pathophysiology in vitro. iPSCs were generated from dermal fibroblasts obtained from a patient with TBK1-associated NTG, via viral transduction of the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC. Retinal progenitor cells and subsequent retinal ganglion cell-like neurons were derived using our previously developed stepwise differentiation protocol. Differentiation to retinal ganglion-like cells was demonstrated via rt-PCR targeted against TUJ1, MAP2, THY1, NF200, ATOH7 and BRN3B and immunohistochemistry targeted against NF200 and ATOH7. Western blot analysis demonstrated that both fibroblasts and retinal ganglion cell-like neurons derived from NTG patients with TBK1 gene duplication have increased levels of LC3-II protein (a key marker of autophagy). Duplication of TBK1 has been previously shown to increase expression of TBK1 and here we demonstrate that the same duplication leads to activation of LC3-II. This suggests that TBK1-associated glaucoma may be caused by dysregulation (over-activation) of this catabolic pathway.

Keywords: TBK1, Autophagy, Glaucoma, Stem cells, iPSC, Retinal ganglion cells

Introduction

Glaucoma is a common cause of vision disability and blindness worldwide [1,2]. A common, defining feature of primary glaucomas is a progressive loss of the retinal ganglion cells and their axons, which form the optic nerve. Elevated intraocular pressure is a major risk factor for primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), however, glaucoma can occur at any intraocular pressure. In normal tension glaucoma (NTG), retinal ganglion cells are lost in the absence of elevated intraocular pressure.

The genetic basis of glaucoma is complex, with some cases due primarily to mutations in single genes (Mendelian forms of glaucoma), while others are due to the combined actions of many genes and environmental factors [3]. Mendelian forms of open angle glaucoma have been associated with mutations in myocilin (MYOC) [4], optineurin (OPTN) [5], WD repeat domain36 (WDR36) [6], neurotrophin 4 (NTF4) [7], TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) [8], and ankyrin binding kinase 10 (ASB10) [9]. Mutations in MYOC are associated with 3–4% of POAG cases that typically have markedly elevated intraocular pressure [10]. Conversely, mutations in OPTN and TBK1 are associated with 1–2% of cases of NTG that do not have elevated intraocular pressure [5,8]. The role of WDR36, NTF4 and ASB10 in glaucoma pathogenesis is currently controversial [11–16].

The mechanism by which duplication of TBK1 causes retinal ganglion cell death and NTG is poorly understood. However, recent data suggests that dysregulation of autophagy, a process by which the intracellular accumulation of proteins, organelles, or pathogens may be eliminated [17], might be important in the pathogenesis of NTG. Autophagy is activated in experimental animal models of glaucoma including optic nerve transection and ocular ischemia model systems [18,19]. Moreover, the NTG genes, TBK1 and OPTN, have both been shown to be important regulators of autophagy. For instance, TBK1 encodes a kinase that phosphorylates OPTN, which then recruits the microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (MAP1LC3B, LC3B) that is instrumental in assembling the autophagosome and initiating autophagy [20]. Duplication of TBK1 gene in NTG patients has been shown to cause increased transcription of TBK1 [8], suggesting that this form of glaucoma may be caused by stimulation of autophagy.

Several eye diseases have been successfully modeled in cell culture, by producing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from accessible, non-ocular patient tissues then forcing the stem cells to differentiate into the specific ocular cell type affected by the disease. Photoreceptor cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells from patients with retinal degenerations, retinitis pigmentosa [21,22] and Best disease [23], have been produced from iPSCs and used to study disease mechanism. More, recently, Minegishi and coworkers reported that the over-expression of a glaucoma causing-mutation in OPTN, Glu50Lys, produces an accumulation of insoluble OPTN protein that can be blocked with chemical inhibition of TBK1 activity in HEK293 cells [24]. This observation was further investigated by using iPSCs and iPSC-derived neural cells from NTG patients with a Glu50Lys OPTN mutation. These studies have confirmed the role of OPTN and TBK1 in the pathophysiology of NTG and suggest that mechanisms to eliminate abnormal proteins and other cellular materials, such as autophagy or the unfolded protein response, may be important in the development of glaucoma. Here we report the development and characterization of iPSCs and retinal ganglion cell-like neurons from unaffected controls and NTG patients with TBK1 gene duplications to investigate the role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of NTG. This represents the first line of iPSC-derived ocular cells that harbor a glaucoma-causing mutation.

Methods and Materials

Patient-derived cells

All experiments were conducted with the approval and supervision of the University of Iowa Internal Review Board (Application #200202022) and were consistent with the Treaty of Helsinki. Skin biopsies were collected from patients after informed consent was obtained and were used for the generation of fibroblasts (isolation performed as described previously) [25–27]. Cells were expanded from patients diagnosed with normal tension glaucoma associated with a TBK1 gene duplication as previously described or from unrelated control subjects that do not have a diagnosis of glaucoma. All subjects were enrolled at the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Generation of iPSCs

iPSCs were generated from human skin cells (fibroblasts) via infection with 4 separate non-integrating Sendai viruses, each of which were designed to drive expression of one of four transcription factors: OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (Invitrogen, A1378001). Fibroblasts plated on six-well tissue culture plates were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 5. At 12–16 hours post-infection, cells were washed and fed with fresh growth medium [minimal essential medium-α, 10% KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.invitrogen.com), 1% primocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, http://www.invivogen.com)]. At 7 days post-infection, cells were passaged onto 6-well Synthemax™ cell culture dishes at a density of 300,000 cells/well, and fed every day with reprogramming media (DMEM F-12 media (Gibco), 20% knockout serum replacement (Gibco), 0.0008% beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1% 100x NEAA (Gibco), 100 ng/ml bFGF (human) (R&D), and 0.2% primocin (Invivogen)). At 3 weeks post-viral transduction, cultures were transitioned to mTeSRmedia, iPSC colonies were picked, passaged and clonally expanded on fresh Synthemax™ plates. A minimum of 3 separate clones was selected for subsequent differentiation and analysis experiments. During reprogramming and maintenance of pluripotency, cells were cultured at 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 37°C.

iPSC differentiation

Neurons with retinal ganglion cell features were cultured as previously described [28]. Adult-derived iPSCs were cultured in mTeSRmedium to maintain pluripotency. Differentiation was initiated by removing iPSCs from the culture substrate via manual passage using Stem Passage manual passage rollers (Invitrogen) followed by resuspension in embryoid body (EB) medium [DMEM F-12 medium (Gibco) containing 10% knockout serum replacement (Gibco), 2% B27 supplement (Gibco), 1% N2 supplement (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco), 1% 100x NEAA (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), 0.2% Fungizone (Gibco), 1 ng/ml noggin (R&D Systems), 1 ng/ml Dkk-1 (R&D Systems), 1 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1, R&D Systems), and 0.5 ng/ml bFGF (R&D Systems)], and plating at a density of approximately 50 cell clusters per cm2 in ultralow adhesion culture plates (Corning). EBs were removed after 5 days in culture (as described above), washed, and plated at a density of 25–30 EBs per cm2 in fresh differentiation medium 1 [DMEM F-12 medium (Gibco), 2% B27 supplement (Gibco), 1% N2 supplement [(Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Gibco), 1%100X NEAA (Gibco), 10 ng/ml noggin (R&D Systems)], 10 ng/ml Dkk-1 (R&D Systems), 10 ng/ml IGF-1 (R&D Systems), and 10 ng/ml bFGF (R&D Systems)] in six-well Synthemax cell culture plates. Cultures were fed with differentiation medium once every other day for 10 days. Cultures were then fed for 6 days with differentiation medium 2 [differentiation medium 1+10 μM of the Notch signaling inhibitor DAPT (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ, http://www.emdbiosciences.com)]. Cultures were next fed for 12 days with differentiation medium 3 [differentiation medium 2+2 ng/ml of acidic fibroblast growth factor (R&D Systems)]. Finally, cultures were allowed to further differentiate for 60 days in differentiation medium 4 (DMEM F-12 medium [Gibco], 2% B27 supplement [Gibco], 1% N2 supplement [Gibco], 1% L-glutamine [Gibco], 1% 100X NEAA [Gibco]).

Immunopanning with anti-THY1 antibody

THY1/CD90-positive neurons were isolated form differentiated heterogeneous retinal progenitor cell cultures using CD90 magnetic MicroBeads (MiltenyiBiotec Cat# 130-096-253), MS columns and a MACS magnetic separator as per the manufactures specifications. Briefly, differentiated cultures were trypsinized, counted using a Tali Image based cytometer (Invitrogen), centrifuged, and resuspended at a density of 107 cells/80 ul of media. 20 ul of CD90 microbeads were added and the cell suspension was incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were subsequently washed, resuspended and loaded into Macs MS columns placed in a MACs magnet. Columns were washed 3 times to remove unbound Thy1-negative cells. Columns were removed from the MACS magnet and cells were flushed into a separate sterile tube using the provided plunger. Thy1-positive cells were plated back into freshly coated culture dishes and used for subsequent analysis.

Teratoma formation

To validate that generated iPSCs were pluripotent, teratomas were generated by IM injection of 2.5 × 106 undifferentiated iPSCs into immunodefficient (SCID) mice. After 90 days, tumors were excised, fixed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned.

Histology

Teratomas were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours prior to dehydration and mounting in parafin wax (VWR). Samples were sectioned at 6 μm and H&E staining was performed using standard protocols.

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution and immunostained as described previously [25,28,29]. Briefly, cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies targeted against NF200 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and ATOH7 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for retinal ganglion cell genesis. Subsequently, Cy2- or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Jackson Immunochem, West Grove, PA) and the samples were analyzed using confocal microscopy. Microscopic analysis was performed such that exposure time, gain, and depth of field remained constant between experimental conditions.

Immunoblotting

For Western blot analysis iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 1% triton X-100, 0.02% NaN3, (Sigma-Aldrich)) and centrifuged. Supernatants were isolated and protein concentrations determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce Chemicals, Rockford, IL). Equivalent amounts of protein (20 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (8–10% acrylamide), transferred to PVDF and probed with primary antibodies targeted against LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and tubulin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Blots were visualized with ECL reagents (GE healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and exposed to X-ray film (Fisher, Pittsburg, PA) or were visualized and quantified using a gel imager (VersaDoc, BioRad, Hercules, CA).

RNA isolation and rt-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini-kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the provided instructions. Briefly, cells were lysed, homogenized and ethanol was added to adjust binding conditions. Samples were spun using RNeasy spin columns, washed, and RNA was eluted using RNase-free water. 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the random hexamer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) priming method and Omni script reverse transcriptase (Qiagen). All PCR reactions were performed in a 40 μL reaction containing 1x PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mMdNTPs, 100 ng of DNA, 1.0 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and 20 pmol of each gene specific primer. All cycling profiles incorporated an initial denaturation temperature of 94C for 10 min followed by 35 amplification cycles with the following conditions, 30 sec at 94C, 30 sec at annealing temperature of each primer and 1 min at 72C with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels (Invitrogen). Gene specific primers (Invitrogen) are given in Table 1. These rt-RCR assays measure overall gene expression and do not differentiate between endogenous or transgene expression.

Table 1.

Gene specific primer sequences used for rt-PCR.

| SOX2 | CAT CAC CCA CAG CAA ATG AC | TUJ1 | GAT CAG CGT CTA CTA CAA CGA G |

| GCA AAC TTC CTG CAA AGC TC | GGC CTG AAG AGA TGT CCA AA | ||

| c-MYC | GCT GCT TAG ACG CTG GAT TT | MAP2 | AGT CCT GAA AGG TGA ACA AGA GA |

| AGC AGC TCG AAT TTC TTC CA | GTG GAG AAG GAG GCA GAT TAG | ||

| Nanog | TTC TTC CAC CAG TCC CAA AG | THY1 | GCT CTC CTG CTA ACA GTC TTG |

| TTG CTC CAC ATT GGA AGG TT | GAT GGG TGA ACT GCT GGT ATT | ||

| KLF4 | AGA AGG ATC TCG GCC AAT TT | NF200 | CGT CAT CAG GCC GAC ATT |

| AAG TCG CTT CAT GTG GGA GA | ATT GAG CAG GTC CTG GTA TTC | ||

| OCT4 | AAC TCG AGC AAT TTG CCA AGC TCC | ATOH7 | TCG CAT CAT CAG ACC TAT GG |

| TTC GGG CAC TGC AGG AAC AAA TTC | CCG AAC AGG ACA AAC TCA CA |

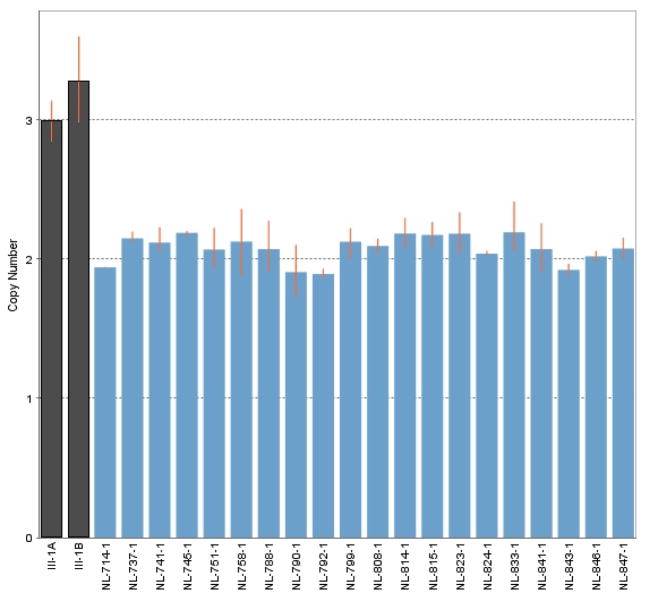

Quantitative PCR assay of TBK1

TBK1 copy number was assessed in DNA from white blood cells and iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells from NTG patient III-1 (Figure 1) known to carry a TBK1 gene duplication and in DNA from the white blood cells of several normal controls using a qPCR assay (TaqMan, BioRad) as previously described [8]. A significant difference was detected between the amount of TBK1 PCR product produced from the DNA of NTG patients and controls using a t-test (p<0.001).

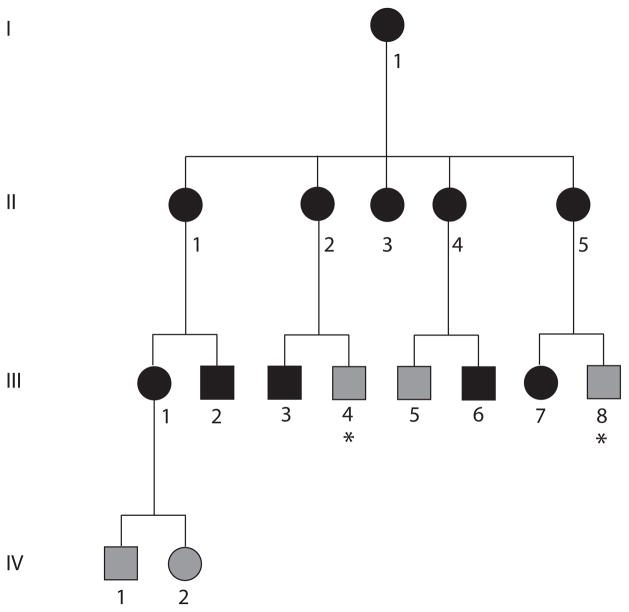

Figure 1.

NTG pedigree 441. Members of this African American family with NTG are indicated with black symbols, while those that did not meet diagnostic criteria for glaucoma but were considered to have unknown glaucoma status because of their age are indicated with grey symbols. Family members with unknown glaucoma status because they were unavailable for examination are indicated with grey symbols and asterisks.

Results

Establishing fibroblast cell lines with TBK1 gene duplication

NTG patients from a large African American pedigree (Pedigree 441, Figure 1) were previously shown to have a 780 kb duplication on chromosome 12q14 that spans TBK1 using a range of techniques including quantitative PCR (qPCR), SNP analysis, comparative genome hybridization (CGH), and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [8,30]. Fibroblast cells were cultured from skin biopsies obtained from an affected member of pedigree 441 with NTG and the chromosome 12q14 duplication (Figure 1, III-1) using previously described conditions [28]. Fibroblasts were also cultured from two healthy individuals with no TBK1 duplication as controls.

Establishing induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines with TBK1 gene duplication (iPSC-TBK1)

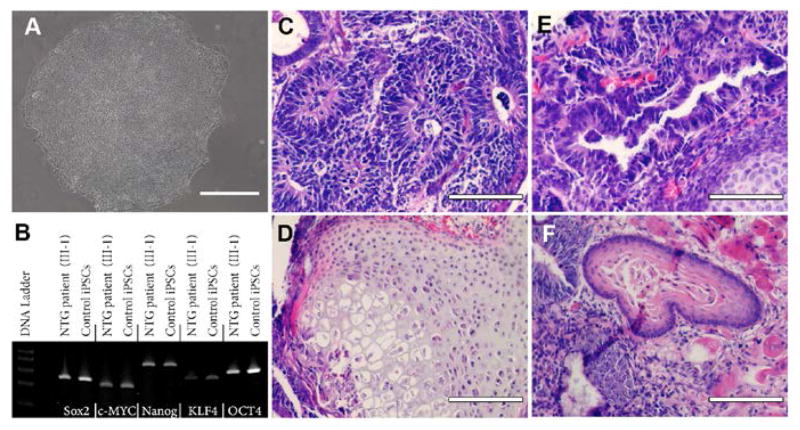

Dermal fibroblasts from a family member with NTG and a TBK1 gene duplication (Figure 1, III-1) were cultured on synthemax cell culture surfaces and reprogrammed via forced expression of the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC. Two to 3 weeks post-transduction, iPSCs colonies containing cells with the typical iPSC morphology began to appear. Individual colonies were manually dissected from neighboring fibroblast cells and cultured on Synthemax™ [28]. Each colony was expanded for 10 passages at which time cells exhibited morphology typical for stem cells including high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio (Figure 2A). iPSCs derived from a NTG patient with a TBK1 gene duplication (Figure 1, III-1) will be referred to as “TBK1-iPSC”, while cells derived from healthy volunteers will be referred to as “WT-iPSC”. Pluripotency was assessed via RT-PCR and teratoma formation assays. Expression of the transcription factors, SOX2, c-MYC, NANOG, KLF4, and OCT4 was detected (Figure 2B). Moreover, following injection into immune-compromised mice, teratomas containing tissues from all three embryonic germ layers were detected (Figures 2C–2F). Collectively these findings demonstrate the successful generation of pluripotent iPSCs from fibroblasts carrying a TBK1 mutation.

Figure 2.

Derivation of iPSCs from a patient affected with TBK1-associated Glaucoma. (A) Phase micrograph of a TBK1-iPSC colony demonstrating a pluripotent morphology. (B) rt-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from WT-iPSCs and TBK1-iPSCs targeted against pluripotency marker expression. (C–F) H&E staining of TBK1-iPSC derived teratomas that show each of the three embryonic germ layers ((C) ectoderm, (D) mesoderm, and (E and F) endoderm). Scale bar=100 microns.

Differentiation of iPSCs into retinal ganglion-like neurons

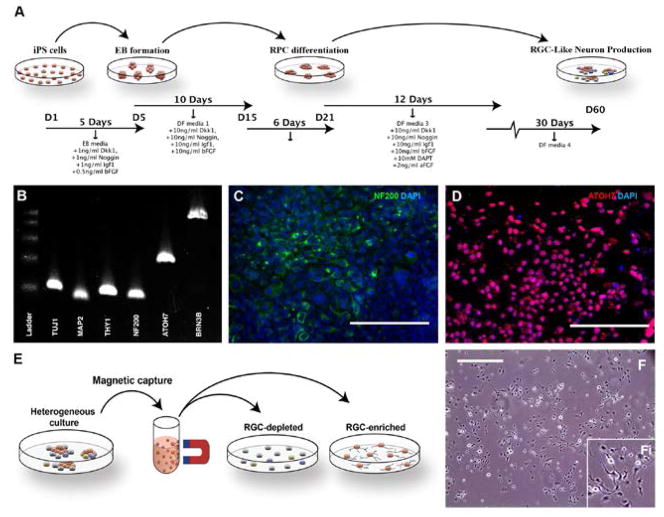

Each of the iPSC lines (TBK1-iPSC and previously generated WT-iPSC lines) were cultured in embryoid body formation media followed by a series of retinal progenitor cell differentiation media containing factors NOGGIN, IGF1, bFGF, DKK-1, and DAPT as outlined in Figure 3A. After 5 days in embryoid body media and a total of 60 days in 4 subsequent different retinal differentiation medias, foci of cells that exhibited morphological features of retinal ganglion cells were observed. These cells were assessed for production of markers that confirm differentiation into retinal ganglion-like neurons. Cells were first tested via RT-PCR for expression of the retinal ganglion/neuronal cell markers TUJ1, MAP2, THY1, NF200, ATOH7, and BRN3B (Figure 3B). Subsequently, immunocytochemical staining targeted against NF200 (Figure 3C) and ATOH7 (Figure 3D) demonstrated that clusters of retinal ganglion cell like neurons were present post-differentiation. Although retinal ganglion cell like neurons could readily be detected in differentiated cultures, for the purpose of subsequent analysis, THY1 magnetic bead purifications/RGC enrichments were performed as depicted in Figure 3E. Following THY1 affinity purification, cells were liberated, re-plated in fresh differentiation media, and cultured for an additional 72 hours to allow the cells to recover and redevelop a neuronal morphology (Figure 3F). Finally, we confirmed that cells differentiated from an NTG patient (Figure 1, III-1) carry the TBK1 gene duplication previously detected in DNA collected from lymphocytes using quantitative PCR (Figure 4). These data indicate that iPSC-derived cells from an NTG patient carrying a TBK1 gene duplication, have key features of retinal ganglion cells and may be a useful tool for studying retinal ganglion cell biology and the mechanism of disease in TBK1-related glaucoma.

Figure 3.

Differentiation of human TBK1-associated iPSCs into retinal ganglion cell-like neurons. (A) Schematic of methods used to produce retinal ganglion cell-like neurons. (B) rt-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from TBK1-iPSC or WT-iPSC derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons shows expression of markers expressed by RGCs. (C and D) Immunocytochemical analysis of TBK1-iPSC derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons targeted against the neural/retinal ganglion cell markers NF200 (C) and ATOH7 (D). (E) Schematic diagram illustrating the paradigm utilized to isolate/purify TBK1-iPSC derived retinal ganglion cell like neurons from a heterogeneous culture of differentiated cells. (F) Microscopic/morphological analysis of TBK1-associated iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons post-magnetic bead isolation. Scale bar=200 microns for panel C and D, and 400 microns for panel F.

Figure 4.

Quantitative PCR assessment of TBK1 gene dose. The number of copies of the TBK1 gene was assessed in genomic DNA collected from white blood cells (A) and from iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells (B) from an NTG patient from family 441 (Figure 1, III-1) and from control subject lymphocytes. This experiment confirms that the iPSC-derived cells carry theTBK1-gene duplication originally detected in lymphocytes.

Assessing activation of autophagy in iPSC derived retinal ganglion cells

Our prior studies of NTG suggest that duplication of TBK1 and increased TBK1 transcription may cause NTG via overactivation of autophagy [8,20,30]. Consequently we investigated this hypothesis, by testing for activation of autophagy in iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells that were produced from an NTG patient with TBK1 gene duplication.

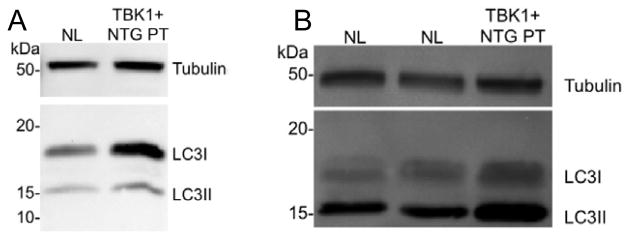

Differentiated cells were first purified using THY1 antibody conjugated to magnetic beads. After 72 hrs post-plating cell lysates were collected and examined for the key marker of activation of autophagy, the lipidated form of LC3 (LC3-II), using Western blot analysis. A low level of LC3-II was detected in iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells from control subjects (Figure 5). However, when compared to a control protein (tubulin), there was a 3-fold increase in LC3-II expression in iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells from an NTG patient with a TBK1 gene duplication. These data demonstrate that an extra copy of the TBK1 gene leads to activation of a critical autophagy protein in the cell type most affected by NTG.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of fibroblast cells (A) and iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells (B) with LC3B antibody. LC3-II, the lipidated isoform of LC3, is more abundant in both cell types that carry a TBK1 gene duplication than in cells with no duplication (NL), but is especially increased in iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons (B). Increased LC3-II suggests that autophagy is activated in iPSC-derived neurons that carry a TBK1 gene duplication.

Discussion

Methods to detect genes that are important in glaucoma pathophysiology have become increasingly successful. Linkage analysis of large pedigrees with Mendelian forms of glaucoma has identified three genes that cause glaucoma (MYOC, OPTN, and TBK1) [4,5,8]. Similarly, genome-wide association studies of large cohorts of patients and controls have detected many risk factors for complex genetic forms of the disease (CAV1/CAV2, CDKN2B-AS1, TMCO1, SIX1/SIX6, and others) [3,31–33]. Studying the biological mechanism by which glaucoma genes and risk factors lead to disease, however, has remained a significant challenge. Studies of ocular tissue from patients with glaucoma caused by a particular gene or risk factor are rarely, if ever, possible given the inaccessibility of the retina and optic nerve from living patients and the absence of donor eyes from patients with known genetic causes of their eye disease.

A successful alternative approach has been to study the ocular tissue of transgenic animals that have been engineered to carry the same disease-causing mutations as human patients with glaucoma. For example, studies of transgenic mice have provided key insights into the pathogenesis of glaucoma caused by MYOC mutations. Mice engineered to carry a human MYOC gene with the Tyr43His mutation develop elevated intraocular pressure and glaucoma that may be related to accumulation of misfolded mutant MYOC protein in key structures of the eye [34,35]. Similar studies of OPTN-related glaucoma with transgenic mice are also underway [24,36]. The obvious successes of studying disease mechanism using transgenic mice are also associated with disadvantages, including the high cost of animal experiments that often have lengthy timeframes. Additionally, the genetic, biochemical, and anatomical differences between animal and human eyes may provide other challenges to studies of glaucoma using transgenic animals. While primary cultures of retinal ganglion cells may be isolated from human donor eyes, such research may be limited by the number and purity of cells that may be collected. Consequently, we have developed an iPSC-based approach to obtain relevant cell cultures from living patients that would otherwise be unavailable to study the pathogenesis of glaucoma.

We have modified our previously reported method for differentiating iPSCs into retinal precursors and photoreceptors [22,25,28] to identify and isolate retinal ganglion cell-like neurons using a novel affinity purification method. We first produced and expanded a heterogeneous mixture of retinal cell precursors and differentiated cells, some of which have features of retinal ganglion cells. Those cells that express the retinal ganglion cell surface marker THY1 were then isolated from the heterogeneous cell culture by immuno-panning with anti-THY1 coated magnetic beads. The result is a highly purified homogeneous culture of cells that exhibit morphological features of ganglion cells and express many key markers for neural and retinal ganglion cells including TUJ1, MAP2, NF200, ATOH7, THY1, and BRN3B.

The two genes known to cause Mendelian forms of NTG, OPTN and TBK1, have been shown to directly interact with each other as key participants in a signaling pathway that activates autophagy. TBK1 phosphorylates OPTN and glaucoma-causing mutations in OPTN have been shown to alter the interaction between TBK1 and OPTN [37,38]. Duplication of the TBK1 gene has also been shown to increase expression of TBK1 [8]. Consequently, we have hypothesized that duplication of the TBK1 gene causes NTG by abnormal activation of autophagy, which may ultimately lead to apoptosis and retinal ganglion cell death. We have used our iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cell-like cultures to begin to explore the mechanism by which TBK1 gene duplications influence autophagy. Here we show for the first time that mutations in glaucoma-causing genes cause increased expression of LC3-II the key marker of activation of autophagy. These data suggest that over-activation of autophagy may be an important factor in the development of NTG, however, more studies to confirm and extend this hypothesis will be needed to establish the role of autophagy in glaucoma. This cell culture system, however, will provide a powerful means for further dissecting the biochemistry of autophagy in retinal ganglion cells and how dysregulation may lead to retinal ganglion cell death and glaucoma. For example, we may use this cell culture system to explore the effects of TBK1 inhibitors on LC3-II production to further support our autophagy hypothesis. This cell culture resource will also facilitate techniques such as Western blot analysis and other protein-based experiments that would not be possible with cells collected from human donor eyes or with eyes from genetically engineered animals. Large, homogeneous cultures of iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons that carry known glaucoma-causing mutations that are expressed at physiological levels by native promoters are now available for such studies to investigate the pathophysiology of glaucoma.

Minegishi and coworkers recently reported producing iPSCs and iPSC-derived neural cells from tissue samples of an NTG patient with a Glu50Lys OPTN mutation [24]. This OPTN mutation caused accumulation of abnormal OPTN protein that likely has a role in the development of OPTN/TBK1-related NTG and supports our hypothesis that dysregulation of cellular mechanisms that respond to eliminate these proteins (such as autophagy or unfolded protein response) may be an important step in the pathophysiology of this disease.

Current therapies for glaucoma (medications, laser procedures, filtering surgeries, and tube shunts) are all designed to slow or halt disease progression by lowering intraocular pressure. Production of iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cell-like neurons will facilitate development of new classes of glaucoma therapies. This cell culture system will allow large scale testing of pharmacological agents that may identify new compounds that have the ability to alter autophagy. These compounds may have neuroprotective features and prevent the activation of autophagy and subsequent loss of retinal ganglion cells. Such drugs may add to the current armamentarium of glaucoma medications to prevent or slow retinal ganglion cell loss from glaucoma. Retinal ganglion cell-like neurons are also the key reagent needed to develop regenerative, cell-based therapies for end-stage glaucoma.

The insights into glaucoma pathogenesis gained from iPSC-based studies will also help researchers design animal models and test new ideas for drug therapy (i.e. inhibition of autophagy) for their ability to slow or prevent vision loss from progression of glaucoma. Also, retinal ganglion cell-like neurons produced from patients’ own skin may eventually be used to replace neurons in their retina and restore vision that was previously lost to glaucoma. Future studies of these iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells will be one of many steps towards better treatment options for vision loss caused by glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants (R01EY018825 and DP2-OD001483-01), BrightFocus, The Polakoff Foundation, and Robert and Sharon Wilson.

Abbreviations

- ABS10

Ankyrin Binding Kinase 10

- ATOH7

Atonal Homolog 7

- CAV1

Caveolin 1

- CAV2

Caveolin 2

- CDKN2B-AS1

Cyclin-dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B Antisense 1

- CGH

Comparative Genome Hybridization

- c-MYC

Avian Myelocytomatosis Viral Oncogene Homolog

- CNV

Copy Number Variation

- iPSC

Induced Pluripotential Stem Cell

- Klf4

Kruppel-like Factor 4

- LC3

Microtubule-associated Protein 1 Light Chain 3

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated Protein 2

- MYOC

Myocilin

- NF200

Neurofilament, Heavy polypeptide

- NTF4

Neurotrophin 4

- NTG

Normal Tension Glaucoma

- Oct4

POU Domain, Class 5, Transcription factor 1

- OPTN

Optineurin

- POAG

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- SIX1

SIX Homeobox 1

- SIX6

SIX Homeobox 6

- Sox2

SRY-box 2

- TBK1

TANK Binding Kinase 1

- THY1

Thymus Cell Antigen 1

- TMCO1

Transmembrane and Coiled-coil Domains 1

- TUJ1

Neuron-Specific Class III Beta-tubulin

- WDR36

WD Repeat Domain36

References

- 1.Kotecha A, Fernandes S, Bunce C, Franks WA. Avoidable sight loss from glaucoma: is it unavoidable? Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:816–820. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;96:614–618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fingert JH. Primary open-angle glaucoma genes. Eye. 2011;25:587–595. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone EM, Fingert JH, Alward WL, Nguyen TD, Polansky JR, et al. Identification of a gene that causes primary open angle glaucoma. Science. 1997;275:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezaie T, Child A, Hitchings R, Brice G, Miller L, et al. Adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma caused by mutations in optineurin. Science. 2002;295:1077–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1066901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monemi S, Spaeth G, DaSilva A, Popinchalk S, Ilitchev E, et al. Identification of a novel adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) gene on 5q22.1. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:725–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasutto F, Matsumoto T, Mardin CY, Sticht H, Brandstätter JH, et al. Heterozygous NTF4 mutations impairing neurotrophin-4 signaling in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fingert JH, Robin AL, Stone JL, Roos BR, Davis LK, et al. Copy number variations on chromosome 12q14 in patients with normal tension glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2482–2494. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasutto F, Keller KE, Weisschuh N, Sticht H, Samples JR, et al. Variants in ASB10 are associated with open-angle glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alward WL, Fingert JH, Coote MA, Johnson AT, Lerner SF, et al. Clinical features associated with mutations in the chromosome 1 open-angle glaucoma gene (GLC1A) N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1022–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804093381503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauser MA, Allingham RR, Linkroum K, Wang J, LaRocque-Abramson K, et al. Distribution of WDR36 DNA sequence variants in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2542–2546. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt AW, Dimasi DP, Mackey DA, Craig JE. A Glaucoma Case-control Study of the WDR36 Gene D658G sequence variant. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:324–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fingert JH, Alward WLM, Kwon YH, Shankar SP, Andorf JL, et al. No association between variations in the WDR36 gene and primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:434–436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.3.434-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Liu W, Crooks K, Schmidt S, Allingham RR, et al. No evidence of association of heterozygous NTF4 mutations in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Hum Genet 2010. 2010;86:498–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao KN, Kaur I, Parikh RS, Mandal AK, Chandrasekhar G, et al. Variations in NTF4, VAV2, and VAV3 genes are not involved with primary open-angle and primary angle-closure glaucomas in an indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4937–4941. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fingert JH, Roos BR, Solivan-Timpe F, Miller K, Oetting TA, et al. Analysis of ASB10 variants in open angle glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4543–4548. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piras A, Gianetto D, Conte D, Bosone A, Vercelli A. Activation of autophagy in a rat model of retinal ischemia following high intraocular pressure. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park HYL, Kim JH, Park CK. Activation of autophagy induces retinal ganglion cell death in a chronic hypertensive glaucoma model. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e290. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Autophagy and innate immunity ally against bacterial invasion. EMBO J. 2011;30:3213–3214. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin Z-B, Okamoto S, Osakada F, Homma K, Assawachananont J, et al. Modeling retinal degeneration using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker BA, Scheetz TE, Mullins RF, DeLuca AP, Hoffmann JM, et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells identify the cilia-related gene male germ cell-associated kinase (MAK) as a cause of retinitis pigmentosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:E569–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108918108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh R, Shen W, Kuai D, Martin JM, Guo X, et al. iPS cell modeling of Best disease: insights into the pathophysiology of an inherited macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:593–607. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minegishi Y, Iejima D, Kobayashi H, Chi ZL, Kawase K, et al. Enhanced optineurin E50K-TBK1 interaction evokes protein insolubility and initiates familial primary open-angle glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3559–3567. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tucker BA, Park I-H, Qi SD, Klassen HJ, Jiang C, et al. Transplantation of adult mouse iPS cell-derived photoreceptor precursors restores retinal structure and function in degenerative mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grinnell KL, Bickenbach JR. Skin keratinocytes pre-treated with embryonic stem cell-conditioned medium or BMP4 can be directed to an alternative cell lineage. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:685–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bickenbach JR. Isolation, characterization, and culture of epithelial stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;289:97–102. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-830-7:097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker BA, Anfinson KR, Mullins RF, Stone EM, Young MJ. Use of a synthetic xeno-free culture substrate for induced pluripotent stem cell induction and retinal differentiation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:16–24. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker BA, Redenti SM, Jiang C, Swift JS, Klassen HJ. The use of progenitor cell/biodegradable MMP2-PLGA polymer constructs to enhance cellular integration and retinal repopulation. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fingert JH, darbro BW, Qian Q, Van Rheeden R, Miller K, et al. TBK1 and Flanking Genes in Human Retina. Ophthalmic Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.3109/13816810.2013.768674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Hewitt AW, Masson G, Helgason A, et al. Common variants near CAV1 and CAV2 are associated with primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat Genet. 2010;42:906–909. doi: 10.1038/ng.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdon KP, MacGregor S, Hewitt AW, Sharma S, Chidlow G, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for open angle glaucoma at TMCO1 and CDKN2B-AS1. Nat Genet. 2011;43:574–578. doi: 10.1038/ng.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramdas WD, van Koolwijk LME, Ikram MK, Jansonius NM, de Jong PTVM, et al. A genome-wide association study of optic disc parameters. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zode GS, Kuehn MH, Nishimura DY, Searby CC, Mohan K, et al. Reduction of ER stress via a chemical chaperone prevents disease phenotypes in a mouse model of primary open angle glaucoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3542–3553. doi: 10.1172/JCI58183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zode GS, Bugge KE, Mohan K, Grozdanic SD, Peters JC, et al. Topical ocular sodium 4-phenylbutyrate rescues glaucoma in a myocilin mouse model of primary open angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1557–1565. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chi Z-L, Akahori M, Obazawa M, Minami M, Noda T, et al. Overexpression of optineurin E50K disrupts Rab8 interaction and leads to a progressive retinal degeneration in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2606–2615. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild P, Farhan H, McEwan DG, Wagner S, Rogov VV, et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science. 2011;333:228–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1205405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton S, Hesson L, Peggie M, Cohen P. Enhanced binding of TBK1 by an optineurin mutant that causes a familial form of primary open angle glaucoma. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]