Abstract

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory, neurodegenerative disease. Diagnosis is very difficult requiring defined symptoms and multiple CNS imaging. A complicating issue is that almost all symptoms are not disease specific for MS. Autoimmunity is evident, yet the only immune-related diagnostic tool is cerebral-spinal fluid examination for oligoclonal bands. This study addresses the impact of Th40 cells, a pathogenic effector subset of helper T cells, in MS. MS patients including relapsing/remitting MS, secondary progressive MS and primary progressive MS were examined for Th40 cell levels in peripheral blood and, similar to our findings in autoimmune type 1 diabetes, the levels were significantly (p < 0.0001) elevated compared to controls including healthy non-autoimmune subjects and another non-autoimmune chronic disease. Classically identified Tregs were at levels equivalent to non-autoimmune controls but the Th40/Treg ratio still predicted autoimmunity. The cohort displayed a wide range of HLA haplotypes including the GWAS identified predictive HLA-DRB1*1501 (DR2). However half the subjects did not carry DR2 and regardless of HLA haplotype, Th40 cells were expanded during disease. In RRMS Th40 cells demonstrated a limited TCR clonality. Mechanistically, Th40 cells demonstrated a wide array of response to CNS associated self-antigens that was dependent upon HLA haplotype. Th40 cells were predominantly memory phenotype producing IL-17 and IFNγ with a significant portion producing both inflammatory cytokines simultaneously suggesting an intermediary between Th1 and Th17 phenotypes.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Multiple Sclerosis, Th40 cells, Diagnosis

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a complex neurodegenerative disease. Multifocal lesions are present on brain and spinal cord, predominantly in white matter although gray matter infiltrates are detected (Lucchinetti et al., 2011). The disease has multifactorial, yet unresolved etiology with genetic, immunologic and environmental factors each presumed contributors. The most common disease course is relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) accounting for 85% of cases with more than 50% of those eventually becoming secondary progressive (SPMS), a more severe course of disease (Hemmer et al., 2002). RRMS patients have CNS lesions characterized by edema and demyelination resulting from an inflammatory process (Miller et al., 1998); in 82% of lesions, CD3+ T cell infiltrates were detected (Lucchinetti et al., 2011). Findings suggest that inflammation mediated by immune activation is prevalent early, an attribute that is consistent with progressive autoimmunity.

Diagnosis of MS is relatively complicated. A wide range of symptoms including: blurred or tunnel vision, general weakness, numbness, prickling pain, muscle spasm(s), tremors, dizziness, headaches, paraparesis, memory loss, speech impediment, attention deficit, decreased concentration etc., are associated with the disease. However these symptoms are likewise associated with other neurologic disorders (OND) and diverse diseases such as vascular diseases, infectious diseases, vitamin B-12 deficiency, hypo-thyroidism and even brain tumors. In order to diagnose MS disease, criteria were defined by what came to be known as the McDonald Criteria, which were revised in 2005 (Polman et al., 2005) and again in 2010 (Polman et al., 2011). The revised criteria require clinical and para-clinical laboratory assessments e.g. composite symptoms with MRI and spinal taps, etc., with demonstrated dissemination of lesions (MRI) in space (DIS) and time (DIT) (Polman et al., 2011). The new criteria however do not advance understanding of the autoimmune contributors to MS. Even with the changes to the McDonald criteria it “remains imperative that alternative diagnoses are considered and excluded” (Polman et al., 2011). The International Panel on Diagnosis of MS stressed that the McDonald criteria “should only be applied in those patients who present with a typical clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) suggestive of MS or symptoms consistent with a CNS inflammatory demyelinating disease” (Polman et al., 2011). CIS can include optic neuritis, brainstem or spinal cord syndromes. While these often are the first clinical presentations of MS, not all CIS patients develop MS, for example in one longitudinal (20 year) study, only 63% of CIS patients advanced to clinically defined MS (CDMS) over that time period (Fisniku et al., 2008). A CIS diagnosis requires symptoms and an abnormal but static MRI scan; thus no DIS or DIT. Another issue is Radiologically Isolated Syndrome (RIS) which involves laboratory findings typical of demyelination but in healthy patients that are asymptomatic or present non-specific symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness) (Miller et al., 2012). Longitudinal studies report that about 30–40% of these patients eventually progress to clinically defined MS.

The revised McDonald Criteria reaffirmed that positive cerebral-spinal fluid (CSF) findings e.g., the presence of oligoclonal (Immunoglobulin) bands, which is at present the only laboratory test that focuses on the autoimmune component of MS, are important “to support the inflammatory demyelinating nature of the underlying condition, to evaluate alternative diagnoses, and to predict CDMS” (Polman et al., 2011). Given the highly invasive and restricted nature of this single test, detecting oligoclonal bands is often not specific i.e. non-autoimmune individuals can have oligoclonal bands and autoimmune individuals may not demonstrate bands; we explored the possibility of a blood test to identify biomarkers for the autoimmune component(s) of MS. In previous work, we defined T cells that defy standard definitional criteria by expressing the antigen presenting cell (APC) associated molecule CD40 and thus have been termed Th40 cells (Siebert et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2004; Waid et al., 2007). Th40 cells were expanded as a percentage of peripheral blood lymphocytes and in terms of absolute numbers in autoimmune diabetes including both the mouse model of type 1 diabetes (T1D) (Waid et al., 2004; Waid et al., 2007) and in human studies (Siebert et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2007). Th40 cells rapidly and consistently transfer T1D to NOD.scid recipients in the mouse model of T1D. In human studies when T1D patients are compared to non-autoimmune controls, Th40 cells are significantly (p < 0.00001) expanded in peripheral blood of both new onset and long term T1D patients and Th40 cells respond to diabetes associated antigens producing Th1, pro-inflammatory, cytokines (Waid et al., 2007).

CD40 is a critical player in several autoimmune diseases including, diabetes, arthritis, colitis, EAE (the mouse model for MS) (Girvin et al., 2002) and in human MS (Benveniste et al., 2004; Giuliani et al., 2005). CD40 as a dominant player in so many diverse autoimmune diseases suggests that it constitutes a critical and early phase autoimmune inflammation marker. The focus of CD40 investigation has been almost exclusively as an antigen presenting cell modulator. Given the importance of CD40 as a central molecule in early auto-inflammation and now understanding that CD40 is expressed on T cells (Carter et al., 2012b; Vaitaitis et al., 2010; Vaitaitis et al., 2013; Vaitaitis et al., 2003; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2008; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2010; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2012; Vaitaitis and Wagner Jr., 2013; Wagner et al., 2002; Waid et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2004; Waid et al., 2007); we considered the possibility of CD40 expression on peripheral CD4+ T cells as constituting a biomarker of pathogenesis in MS.

In the current study, we show that MS subjects, like T1D subjects (Waid et al., 2007), have a significantly expanded number of Th40 cells (CD4+CD40+) compared to control subjects in peripheral blood. In a cohort of 48 patients, HLA haplotypes were determined and as expected HLA-DR15 and DQ6 were predominant, but DR3, DR4, and DQ8 subjects that are more closely associated with T1D and rheumatoid arthritis rather than MS were identified. Regardless of HLA expression Th40 cell levels were significantly elevated during MS, suggesting a measure other than HLA that correlates more consistently with disease occurrence. Th40 cells from MS patients typically demonstrated a clonal expansion of TCRVα8.3+ cells and recognized CNS antigens including MBP, MOG and PLP peptides in an HLA haplotype restricted manner. Th40 cells in MS are predominantly memory phenotype and mainly produce IL-17, but a significant portion produce both IL-17 and IFNγ simultaneously. These data suggest a possible biomarker that not only associates a definable T cell subset with MS, but improves evidence for a new autoimmune based, rapid blood test that avoids the more invasive spinal tap, for MS disease diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Subjects diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, meeting the McDonald criteria, were recruited from the Rocky Mountain Multiple Sclerosis Center and the Department of Neurology of the University of Colorado Denver Medical Campus. Patients included relapsing/remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), primary progressive MS (PPMS) and control subjects. Autoimmune controls included type 1 diabetes (T1D) subjects recruited from the Barbara Davis Childhood Diabetes Center (BDC), Denver CO. T1D subjects meet American Diabetes Association and the National Institutes of Health criteria for disease. Chronic disease controls included diagnosed T2D patients with no reported infections. Subjects had no infections or complicating diseases at time of examination. All subjects were recruited under a Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) approved protocol and signed informed consent forms. Our human participant policy conforms to the uniform requirements of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

| Controls | T1D | T2D | CDMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Range | 17 – 63 | 12 – 65 | 22 – 62 | 20 – 58 |

| Median Age | 40.2 ± 11.4 | 40.3 ± 8.5, | 47.7 ± 10.5 | 41.7 ± 10.5 |

| Average Disease Duration |

N/A | 15 years | 17 years | 12 years |

| Gender: Female/Male (Number of subjects) |

42/40 | 48/47 | 32/36 | 42/26 |

Blood Samples

Venal blood was drawn into tubes with an anti-coagulant, diluted 1:1 with PBS and separated over a ficoll gradient that was centrifuged for 30 minutes at 400 ×g. The layer of PBMC was recovered from the buffy coat and washed twice and pelleted (200 × g) in PBS/0.5% BSA/2mM EDTA.

Staining

Cells were stained using antibodies for CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD45 that were purchased from Miltenyi (Auburn, CA) and FoxP3, IFNγ, and IL-17A were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Anti-CD40 (clone G28-5) maintained in house conjugated to AF405, AF647 or AF647/750. Cells were incubated with appropriate antibodies for 30 min, and washed with PBS/0.5% BSA/2mM EDTA. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed by first fixing the cells with 2% paraformaldehyde for 3–5 minutes followed addition of PBS/0.5% BSA/2 mM EDTA and pelleting of the cells. Then cells were stained in eBioscience permeabilization buffer (cat# 00-8333-56) for 15–20 minutes. Cells were washed and assayed on a Miltenyi MACSQuant bench-top flow cytometer with 7 color compensations determined for human cells.

Cell Sorting

Following Ficoll purification of PBMC, cells were incubated with anti-HLA antibody micro-beads (Miltenyi) for 30 minutes with gentle rocking. Cells were passed through a Miltenyi AutoMACS cell sorter set on deplete-s. Positive fraction was considered antigen presenting cells (APC). Helper T cells were purified by sorting HLA-depleted fractions with CD4 micro-beads (Miltenyi) followed by AutoMACS set to possel-s. Cell purity was > 98% as determined by staining and flow cytometry.

Antigen assays

Purified APC were exposed to antigens at concentration of 5 µg/ml in a 96 well u-bottom plate for 8–12 hours and then the cells were twice exposed to a UV light source, UV Strata-link 2400 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA), for 1 minute to irradiate APC. MS associated antigens include MOG35–55, MEVGWYRPPFSRVVHLYRNGK; MOG99–107, FFRDHSYQE; PLP103–120, LVERGNHSKIVAGVLGLI; MBP146–170 AQGTLSKIFKLGGRDSRSGSPMARR; and MBP83–102, ADPGSRPHLIRLFSRDAPGR. PEDIACEL composed of purified diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, acellular pertussis vaccine, inactivated poliovirus, and haemophilus influenza type b polysaccharide was used as a positive control. CD4 cells were labeled with CFSE and 5 × 104 cells were incubated in 96 well plates with equivalent numbers of APC. Cells were incubated for 7 days then stained with CD4, CD8, CD40, CD25 and CD45 and examined via flow-cytometry using the Miltenyi Macs-Quant.

HLA Testing

HLA haplotypes were determined by the HLA core facility at the Barbara Davis Childhood Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus. HLA is determined by RT-PCR using appropriate primers for HLA-DRs and DQs from blood cells.

Results

Th40 T cells are prevalent in MS

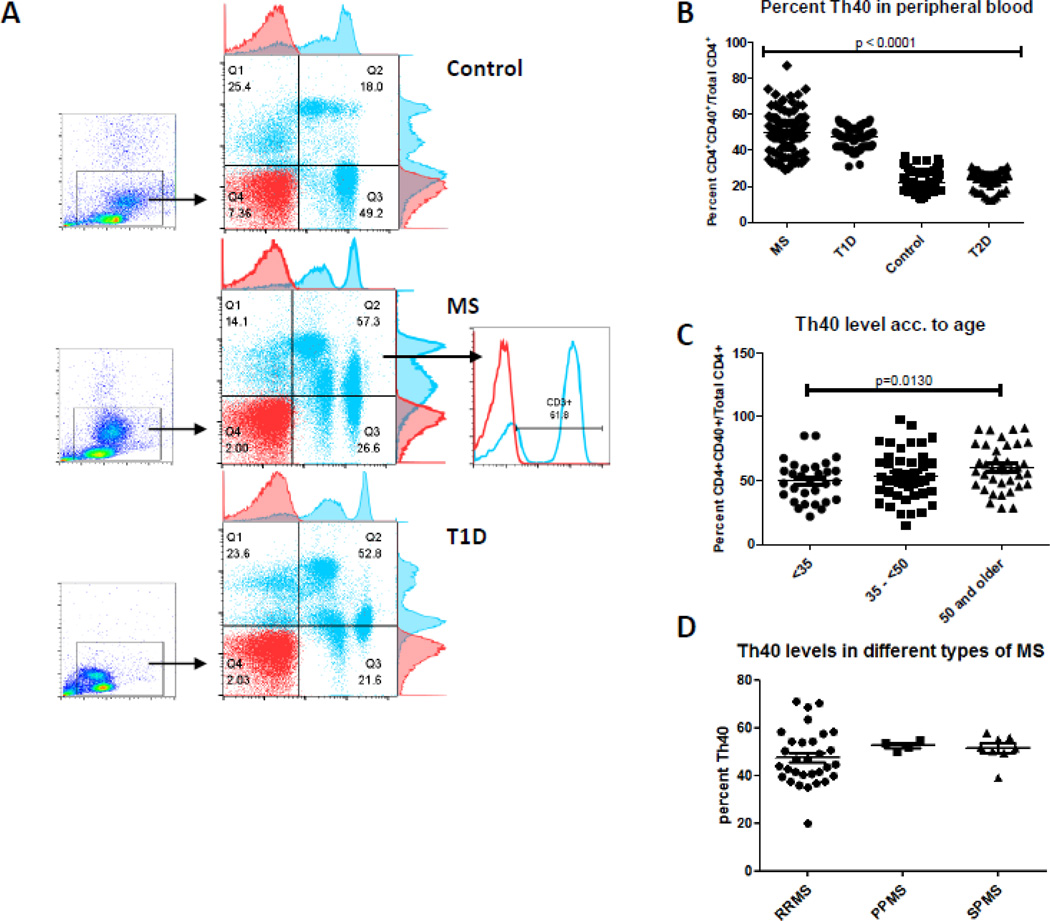

In a blinded study, we examined peripheral blood to determine levels of Th40 cells. Subjects diagnosed with MS were compared to non-autoimmune controls and to an established autoimmune disease, T1D, as well as to a chronic but non-autoimmune disease, type 2 diabetes (T2D). MS subjects (41.73 ± 10.5 years old) were age matched to non-autoimmune (40.2 ± 11.4 years old) and to T1D (40.3 ± 8.5,) autoimmune control subjects. Like in T1D, MS subjects have a substantially increased percentage of Th40 cells in peripheral blood when compared to non-autoimmune controls (Fig. 1 A and B; CD4+CD40+ T cells/Total CD4+). However, while the mean percentage of Th40 is comparable between MS and T1D, there is a broader range in the Th40 levels within the MS cohort than within the T1D cohort (Fig. 1B). Th40 cells from MS subjects express high levels of CD3, a classic T cell molecule (Fig. 1A). The majority of CD40 expressing cells from T1D patients occur as CD4lo (Fig. 1A). In MS subjects, a substantial portion of the CD40+ cells occur in the CD4lo population, however, in many patients CD40+ cells were also found in the CD4hi population (analyzed further in Fig.2). In previous work we showed by western blot that while the cell surface expression of CD4 is lower, the overall cellular CD4 levels are identical (Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2008). This suggests cell surface down-regulation of CD4, potentially constituting an activated or memory phenotype status. Because of the CD4lo status, this population of cells typically has been overlooked.

Figure 1. Th40 cell percentage is expanded in MS.

Blood samples were taken from diagnosed MS, including RRMS, PPMS and SPMS subjects and non-autoimmune controls. Blood samples likewise were taken from T1D and T2D subjects. Samples were analyzed in a blinded study. (A) Dot plots were generated following CD4, CD3 and CD40 staining. Levels of CD4 (x-axis) versus CD40 (y-axis) are shown. Gates were set from isotype controls for each group. Gated CD4+CD40+ cells demonstrate CD3 expression (histogram, gray line) above isotype control (red line). (B) Percent of CD40+ cells within the CD4+ compartment from 168 MS, 98 T1D, 112 non-autoimmune control and 62 T2D subjects. (C) Th40 level analysis based on age groups (< 35 years old; 35 – < 50 years old: 50 and older). (D) Comparison of RRMS (48 randomly chosen subjects), PPMS (6 subjects) and SPMS (8 subjects). Statistics were non-paired t-tests determined using the GraphPad Prism program and ANOVA, Tukey test.

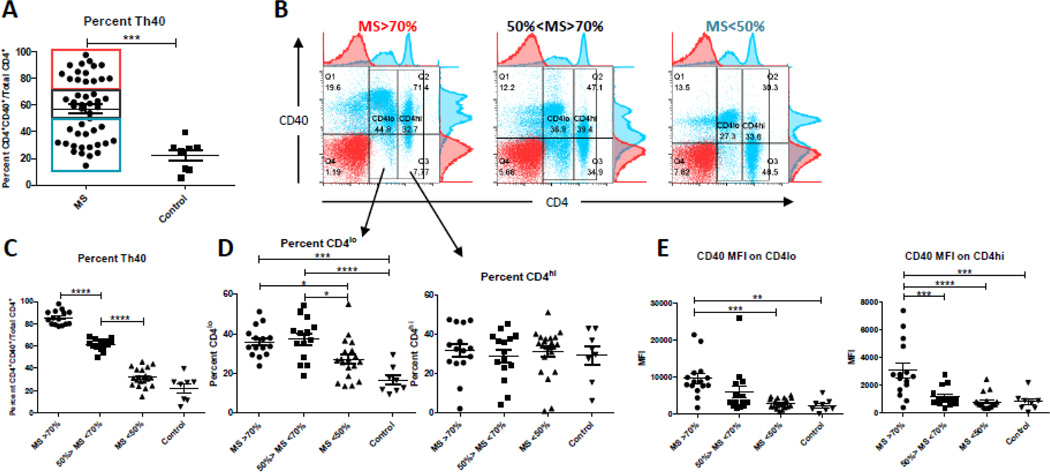

Figure 2. CD40+ T cells occur both as CD4lo and CD4hi T cells in MS.

MS patient samples (n=48) that had been stained with exactly the same stain sets of antibodies were compared to control subjects (n=8) for CD4 expression level (CD4hi or CD4lo) as well as CD40 intensity within the CD4hi and CD4lo populations. Due to the large range in Th40 levels, MS samples were divided into groups of high (MS>70%), intermediate (50%>MS<70%), and low (MD<50%) Th40 levels. Cells were gated on live cells then CD4 and CD40 was gated based on isotype controls. (A) Th40 levels (CD4+CD40+ of total CD4+ T cells) in MS samples compared to control. Red box – MS>70%; Black box – 50%>MS<70%; Blue box – MD<50%. (B) Dot plots of CD4 versus CD40 stains representative of the three Th40 level groups in MS. Red – isotype control; Blue – CD4/CD40 stained. Further gates were set around CD4lo and CD4hi populations for analysis in D and E. (C) Th40 levels within the three groups compared to each other and control. (D) Percent CD4lo and CD4hi within each of the MS groups and control. (E) CD40 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) within the CD4lo and CD4hi gated populations in the different MS groups and control. Statistical analysis was done by One-way Anova followed by a Bonferroni post-test; **** - p<0.0001, *** - p<0.001, ** - p < 0.01, * - p between 0.01and 0.05.

MS is a chronic disease; therefore we compared Th40 levels from T2D patients, a chronic but non-autoimmune disease (Fig. 1B). Th40 cell percentages from T2D subjects were identical to non-autoimmune controls; thus the chronic disease state does not account for the expansion of Th40 cells (Fig. 1B). We further analyzed Th40 levels based on different age groups and found that there was a significant difference in the percentage between the younger (<35 years old) group and the oldest (50 years and older) group, a finding different from what we previously found in T1D where no such difference was discernable (Waid et al., 2007)(Fig. 1C). We speculated that the relapsing/remitting course may be reflected in Th40 cell levels so we further characterized levels of Th40 cells comparing RRMS versus PPMS and SPMS (Fig. 1D). The cohorts of PPMS and SPMS were smaller than RRMS; but levels of Th40 were more tightly grouped in PPMS and SPMS. The wide range of Th40 cells occurred in RRMS, which may reflect the variable nature of the relapsing/remitting disease course.

CD40+ T cells can occur in both the CD4lo and CD4hi populations in MS

The range of Th40 levels was quite broad in MS and there were patients with a higher level of Th40 cells occurring as CD4hi. We have previously demonstrated that CD4lo cells express CD4 protein at similar levels to CD4hi but the protein is mostly intracellular (Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2012). The CD4lo cells also appear to have a more activated phenotype than the CD4hi cells (Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2012). Therefore we assessed the CD4lo/hi levels and CD40 expression intensity within those in the MS cohort. We analyzed a subset of 48 patients that had been stained with the exact same antibody/color combinations. Three distinct groups of Th40 levels were discernable, above 70%, between 50 and 70%, and below 50% (Fig. 2 A and B; red, black, and blue boxes in graph; representative dot plots of CD4 vs. CD40 are shown for each group). When the samples were separated into each of the three groups it was apparent that the Th40 levels in each group were significantly different from the others (Fig. 2 C; p<0.0001). Additionally, the MS<50% group was not significantly different from the control group. When gated on CD4lo, the two higher Th40 level groups had significantly higher levels of CD4lo cells than the MS<50% and the control group (Fig. 2D). When gated on CD4hi, there was no difference between the groups (Fig. 2D). Analysis of the intensity of CD40 expression on the CD4hi/lo groups revealed that in the MS>70% group the CD40 expression was significantly higher, on a per cell basis, in both the CD4lo and CD4hi subpopulations than in the same populations in any of the other groups or the control group. While we currently have no availability of data regarding relapses and medications in the patients it is possible that during a relapse the Th40 population(s) surges accounting for the highest Th40 level group and that remission and/or medications cause the Th40 population to retract accounting for the two lower Th40 level groups.

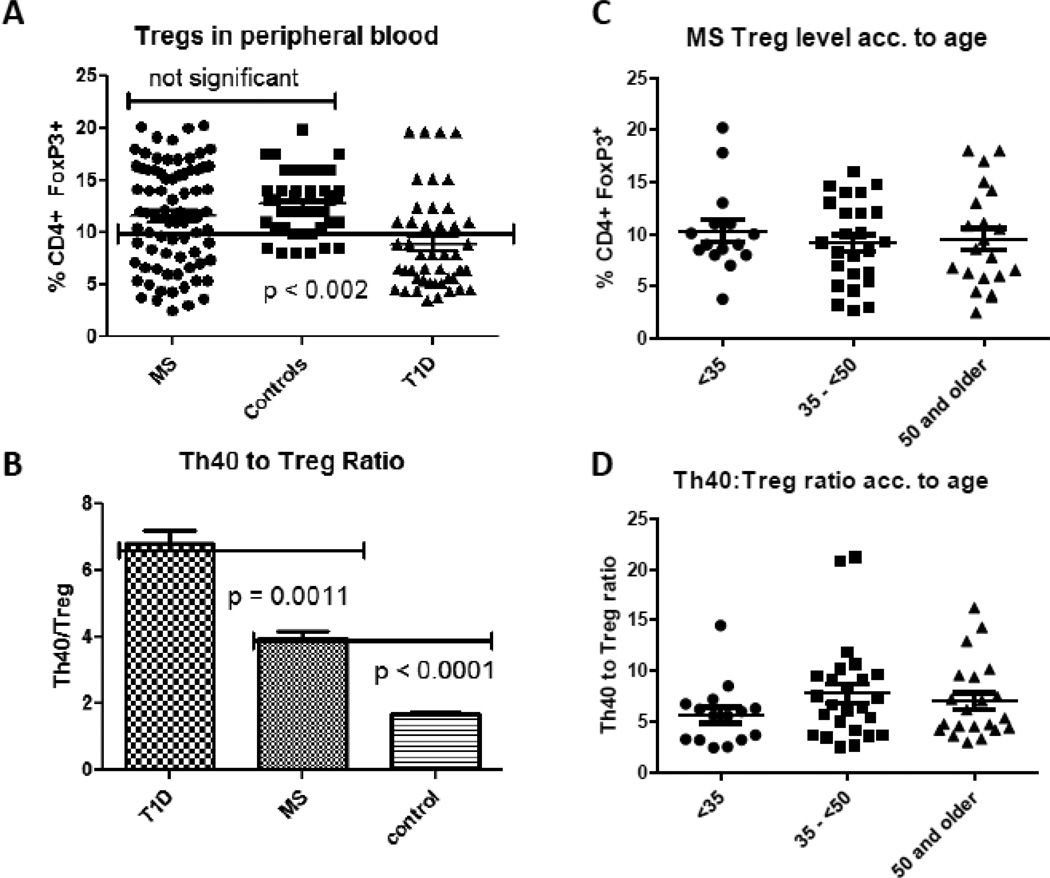

Tregs in MS

A seminal question in autoimmunity is the role of Tregs. It is assumed that during autoimmunity, Tregs, which are responsible for some degree of tolerance, are somehow deficient, either in total number or in function. Furthermore that deficiency is presumed to be a predominant source for breach of tolerance. In the mouse model of T1D we recently reported that pathogenic effector cells can express then lose Foxp3 (Vaitaitis et al., 2013). It is important therefore to correctly define Tregs. We compared the percentage of classically defined Tregs, CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ cells, in MS subjects to Tregs from non-autoimmune control and T1D patients (Fig. 3A). We found that Treg levels in MS subjects trended lower when compared to non-autoimmune control subjects (11.6 versus 12.7) but were not significantly different (p = 0.1657, two-tailed t test). This finding is counter-intuitive given that Treg numbers are considered to be lower in all autoimmune diseases. We further compared Treg percentages from age matched T1D subjects, representing another chronic autoimmune disease. Treg levels in T1D subjects were significantly lower than levels in MS subjects as well as control subjects (p < 0.002, ANOVA). This observation would be expected if Treg numbers or function is dysregulated. The MS subjects in this study were all RRMS. A more telling statistic is the ratio of Th40 to Treg in MS (4.2 ± 0.24) compared to non-autoimmune controls (1.7 ± 0.86) or T1D (6.82 ± 2.93) [Fig. 3B]. While it was noted that some MS subjects had high Treg levels, those same patients exhibited very high Th40 cell levels; thus the Th40 to Treg level remained significantly above non-autoimmune controls but lower than T1D subjects that demonstrated an even higher Th40 to Treg ratio (Fig. 3 B). These data may suggest that dysregulation lies more prominently in Th40 cells rather than Tregs in MS, but in T1D dysregulation may occur in both Tregs and Th40 cells. As we found in figure 1 that there was a difference in Th40 levels between the youngest and oldest age groups of patients we performed the same analysis for the Treg levels. We found no statistical difference between Treg levels or Th40:Treg ratio in the different age groups (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3. Treg levels in MS subjects.

Percent Tregs was defined as CD4+CD25hiFOXP3+ cells in peripheral blood of RRMS, non-autoimmune control and T1D subjects. Subjects were age and gender matched as in Figure 1. MS and T1D patients had well established disease courses, diagnosed for greater than 5 years. Cells were stained with CD4, CD25 and intra-cellular FOXP3. Tregs were designated as CD25hi, CD4+, and FOXP3+. (A) The percentage of Tregs from individual subjects was compared. Each symbol represents an individual patient (B) The ratio of Th40 cell to Tregs within each individual was determined. Bar graphs represent 16 individuals from each group. (C) Treg level analysis based on age groups (< 35 years old; 35 – < 50 years old: 50 and older). (D) Th40 to Treg ratio analysis based on age groups (< 35 years old; 35 – < 50 years old: 50 and older). Statistics were non-paired t-tests and Tukey ANOVA analysis determined using the GraphPad Prism program.

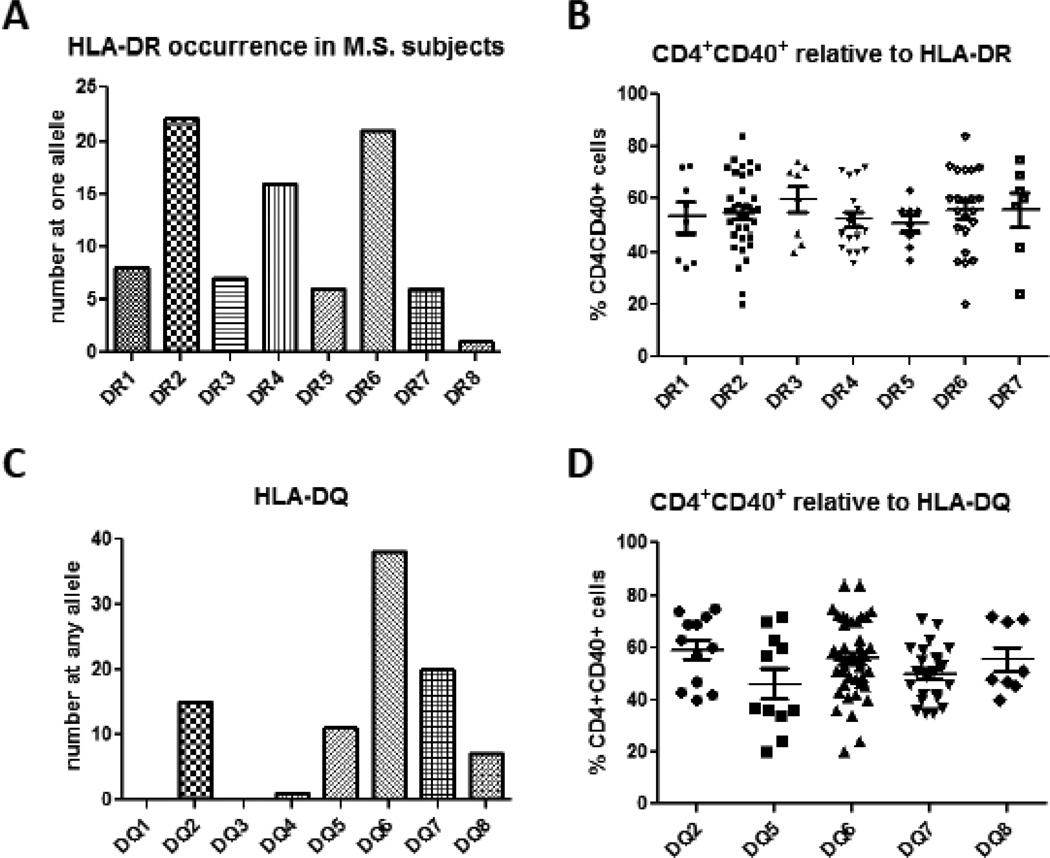

Th40 levels relative to HLA haplotype

Genome wide association studies (GWAS) have provided some clues for biomarkers in autoimmune diseases including MS. For example, the most reliable and descriptive biomarker in MS thus far determined is HLA-DRB1*1501 originally known as HLA-DR2 but also referred to as DR15 (Hoffjan and Akkad, 2010; International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics et al., 2007; Sawcer et al.). We examined HLA expression in a cohort of 48 MS subjects that included RRMS and SPMS patients. As predicted, the most common HLA-DR allele expressed was HLA-DRB1*1501 (DR2 or DR15). Interesting though, in our cohort HLA-DR6 occurred as frequently as HLA-DR2 (Fig. 4A). The third most commonly occurring allele was HLA-DR4, which is associated with type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis (Angelini et al., 1992; Thorsby and Ronningen, 1993). We found that many MS subjects from our cohort did not carry the DR2 haplotype. In fact several MS subjects carried DR4/DR3 that is highly associated with T1D (Steck and Rewers, 2011) (Fig. 4A). In our MS cohort 2 subjects demonstrated T1D comorbidity. Th40 percentages were determined relative to each HLA-DR haplotype. Although a wide range of Th40 percentages occurred, the mean percentage of Th40 cells did not statistically alter relative to any HLA haplotype (Fig. 4B). The widest range of Th40 cell levels in MS occurred within the DR6 and DR2 haplotypes (range = 64). Subjects carrying DR1 and DR3 had the narrowest range of Th40 cell percentages (range = 17 and 18.5 respectively). In subjects whose Th40 cell percentages were above 60% the more common HLA haplotypes were DR6 and DR2, although several subjects carrying DR3 or DR4 had Th40 cell percentage above 60%. Importantly for each HLA haplotype in MS, the Th40 level was significantly (p < 0.001) increased compared to HLA matched controls (Supplemental Figure 1). This included MS subjects who do not carry the HLA-DR2, MS predictive haplotype.

Figure 4. Th40 cell percentages relative to HLA haplotype.

(A) HLA-DR haplotypes were determined in a cohort of 48 RRMS subjects. Each HLA allele was considered individually. (B) Th40 cell percentages were determined within each haplotype. Although each haplotype showed a wide range in Th40 percentage, there were no statistical differences in means of Th40 cell percentages relative to any HLA haplotype within the MS cohort. (C) HLA-DQ haplotypes were determined in the 48 RRMS subjects. (D) Th40 cell percentages were not significantly different relative to any given HLA-DQ allele. Statistics were non-paired t-tests and ANOVA determined using the GraphPad Prism program.

We examined the DQ alleles finding a predominance of DQ6 (Fig. 4C), which was expected. In our cohort DQ7, DQ2 and DQ5 were sequentially the next most common haplotypes (Fig. 4C). For Th40 levels, the same observations occurred for HLA-DQ haplotypes as for DR haplotypes; there were no statistical differences in Th40 cell levels relative to DQ allele expression (Fig. 4D). These data demonstrate that regardless of HLA haplotype during MS, Th40 cell levels are significantly increased relative to controls. Importantly in MS patients who do not carry the predictive HLA-DRB1*1501 allele, those subjects still had elevated Th40 cell levels (Fig 4B and Supplemental Figure 1). Conversely, several non-autoimmune control subjects do carry the HLA-DRB1*1501 allele, but do not have elevated Th40 cell levels (supplemental figure 1). These data argue that Th40 cell percentages are independent of HLA haplotype and are a stronger predictor for MS susceptibility or diagnosis.

T cell limited clonality in MS

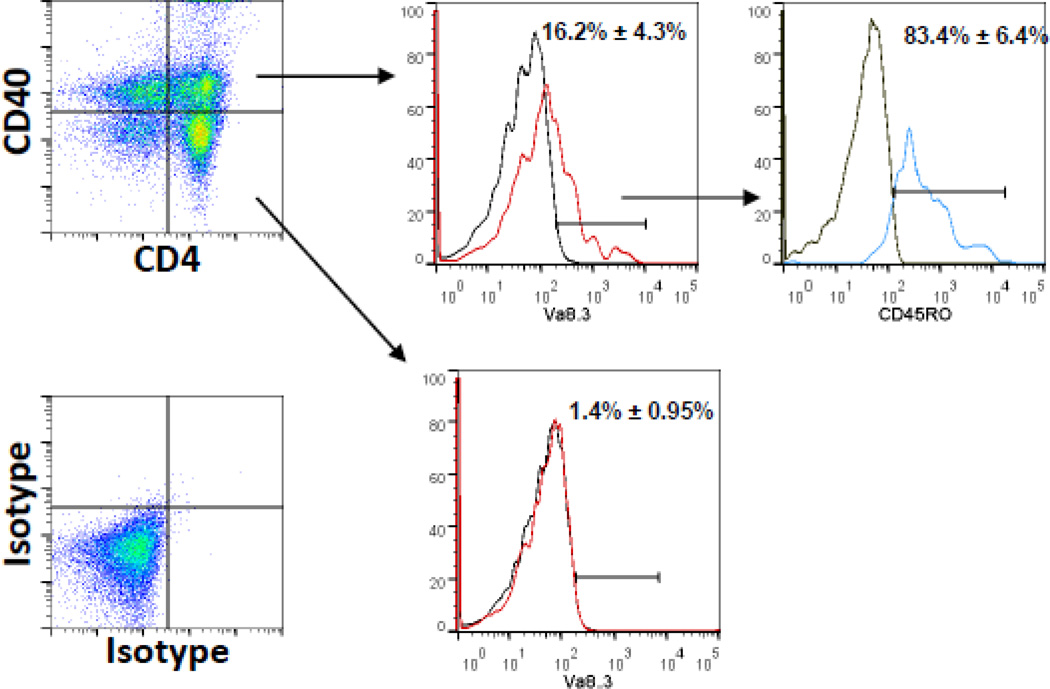

Models for autoimmune disease often demonstrate T cell clonal expansions (Fox, 1996; Wucherpfennig and Hafler, 1995). In the EAE model of MS, T cell clonality has been suggested (Harrington et al., 1998; Huseby et al., 2001). TCR transgenic mice have been generated that spontaneously develop EAE (Goverman et al., 1993) further emphasizing clonal contributions in the disease process. We examined for a clonal expansion in our MS cohort, focusing on Th40 cells from RRMS patients. In a cohort of 48 patients, we determined that 37.5% demonstrated a detectable increase (16.2% ± 4.3%) in the TRAV8-3 gene product TCR Vα8.3 (Fig. 5). This particular TCR Vα has been associated with autoimmunity in human subjects (Kent et al., 2005). TCR Vβ usage was not examined; therefore true clonality was not assessed. The majority of those TCR Vα8.3 cells (83.4% ± 6.4%) were CD45RO+, a memory phenotype (Fig. 5). In none of the subjects examined did the CD4+CD40− cells demonstrate TCR Vα8.3 expansions (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Limited T cell clonality in Th40 cells from a RRMS cohort.

A cohort of 48 RRMS subjects was examined for potential T cell clonality. Purified peripheral T cells were stained for CD4, CD40, CD45RO and TCR Vα8.3. CD4 and CD40 expression were determined above isotype control (shown). The percent Vα8.3+ cells (red line) above isotype controls (grey line) were determined in CD4+CD40+ and CD4+CD40− populations. 16 out of 48 subjects demonstrated an increase in Vα8.3+ T cells only within the CD4+CD40+ population. Gated Vα8.3+ cells were examined for CD45RO, memory phenotype.

Th40 cell response to CNS antigens is HLA restricted

As a disease predictive mechanistic approach we addressed whether Th40 cells from MS subjects are Central Nervous System (CNS) self-antigen responsive. The antigens were peptide derivatives from MOG, MBP and PLP proteins each of which has been associated with MS and the EAE model of the disease (Arbour et al., 2006). Analysis was done relative to HLA haplotype. When the DR2 allele was present at one allele with the other allele being any haplotype, the best antigen response by Th40 cells was to MOG99 peptide followed by the PLP103 peptide (Fig. 6A). The least reactive peptide was MBP83. It is notable however that there was no statistical difference between any of the peptides that were tested. When the DR6 haplotype was a fixed allele and any haplotype occurred at the other allele, Th40 cells responded quite differently to the antigens (Fig. 6B). The peptides inducing the best response were MBP83 and PLP103. In our cohort there were no DR2/DR2 individuals. When DR6 occurred at both alleles, the PLP103 antigen induced the best Th40 response, which was significantly above MBP146 (the worst response antigen) or either MOG peptide (Fig. 6C). The most variation of response (most significant differences) occurred when DR2 and DR6 were co-expressed the prominent response antigen was MOG35 (significantly greater than any of the tested antigens including the PED positive control) followed by PLP103 that was significantly greater than the remaining antigens tested (Fig. 6D). There was no response to MBP146 and significantly less response to MOG99.

Figure 6. Antigen response of Th40 cells from MS subjects.

Blood collected from 20 RRMS subjects was separated into APC and T cell fractions. APC were exposed to peptide antigens then fixed by U.V. Strata-link exposure. T cells were CFSE labeled. T cells then were exposed to autologous APC/Ag for 7 days and total proliferation above negative controls was determined. Percent response was determined by subtracting background proliferation from antigen induced proliferation. Data were analyzed relative to HLA-DR haplotype. (A) Data from patients with DR2 at either allele with an open second allele; (B) DR6 at either allele with open second allele; (C) DR6 at both alleles; (D) DR2 at one allele and DR6 at the second allele; (E) DR4 at either allele with an open second allele; (F) DR4 at one allele and DR2 at the second allele; (G) DR4 at one allele and DR6 at the other allele. Statistics were unpaired t-tests or Mann-Whitney ANOVA analysis performed by the GraphPad Prism program. Statistically significant differences are noted.

The third most common DR allele expressed in our MS cohort was DR4, which GWAS has associated with T1D susceptibility (Steck and Rewers, 2011). Interestingly Th40 cells from DR4 expressing MS subjects responded to MOG99 and equally to PLP103 and respond to both MBP peptides with very little response to MOG35 (Fig. 6E). When DR4 is co expressed with DR2 the response to MOG99 remains high while response to MBP83 is diminished (Fig. 6F). When DR4 is co expressed with DR6 the MOG99 response is unaffected, but response to MBP83 is increased (Fig. 6G). Cumulatively these data demonstrate that Th40 cells do respond to classic MS associated antigens, but with varying degrees depending upon the HLA haplotypes can present the described antigens. The data suggest a varied TCR repertoire within Th40 cells, but also suggest epitope spreading; this is because the total response across all antigens is greater than 100%. Epitope spreading has been well described in EAE the mouse model for MS (McMahon et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2007; Smith and Miller, 2006; Zhang et al., 2004). These data suggest that some Th40 cells are responding to more than one single peptide.

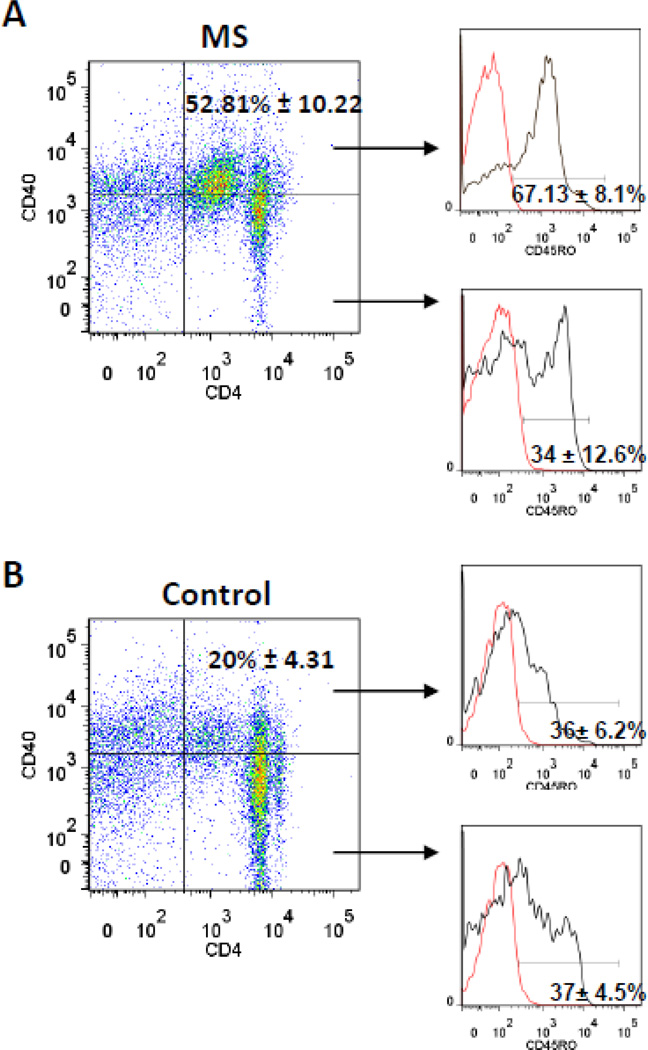

Th40 T cells and memory/effector phenotype

We further characterized memory phenotype within the total Th40 cell population from MS subjects. The majority (67.13% ± 8.1%) of Th40 cells from MS subjects were CD45RO+, a memory T cell biomarker (Fig. 7A); while a significantly (p < 0.001) smaller portion (34 ± 12.6%) of the CD4+CD40− T cell population was CD45RO+. Non-autoimmune subjects had significantly fewer Th40 T cells overall and a smaller portion (36% ± 6.2) of Th40 cells were CD45RO+ (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, there was no difference between Th40 T cells and CD4+CD40− T cells with regard to CD45RO expression in those control subjects (Fig. 7B). These data demonstrate that MS results in increases in memory T cells within the Th40 cell population and not within CD4+CD40− cells. It has been reported that memory T cells from MS patients do not rely on CD28 signaling (Lovett-Racke et al., 1998). CD40 acts as a T cell co-stimulus (Baker et al., 2008), therefore an important alternative for memory T cell costimulation, CD40, emerges.

Figure 7. CD45R0 memory T cell marker in Th40 and CD4+CD40− T cells.

T cells were selected by depleting HLA+ cells from isolated lymphocytes then stained for CD4, CD40 and CD45RO in (A) MS subjects, 48 total subjects and age matched (B) non-autoimmune control, 48 total subjects. Dot plots show representative CD4 versus CD40 levels with gates set from isotype controls. Levels of CD45RO+ cells were determined (black line) above isotype controls (red line) in Th40 cells, top histogram of each set, and in CD4+CD40− cells, bottom histogram in each set. The CD45RO+ population in Th40 cells from MS is statistically (p < 0.001) different from CD45RO+ CD4+CD40− cells and from both populations of cells from non-autoimmune controls. Mean percentages are shown +/− SEM. Statistics were ANOVA, Tukey comparison, using Graph Pad Prism program.

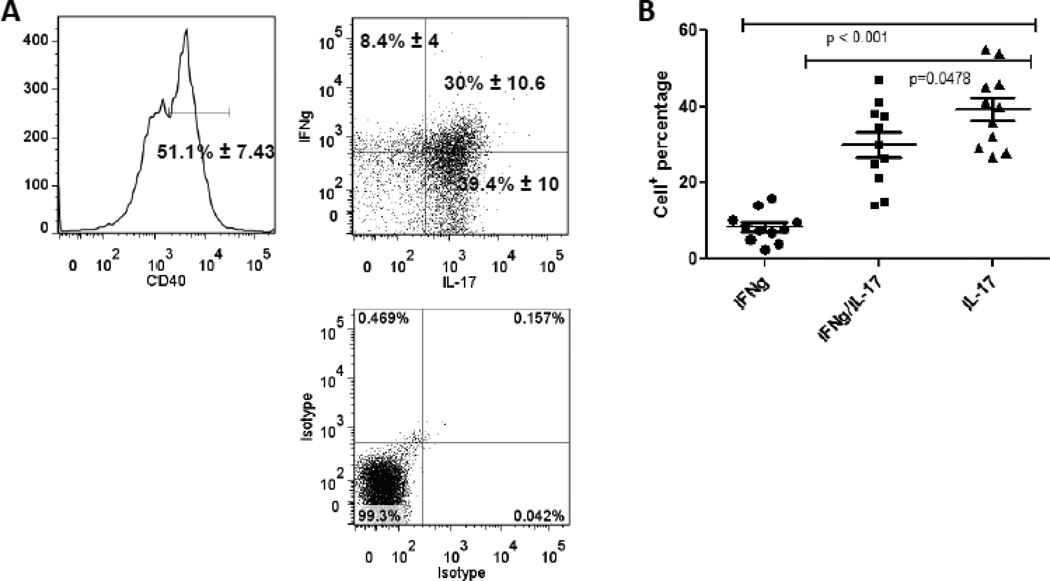

Th40 cells and cytokine production in MS

Inflammatory cytokines including IFNγ, a Th1 cytokine (Anderson and Rodriguez) and IL-17A, the defining cytokine for the Th17 subset (Graber et al., 2008) are reported to promote MS progression. We determined that memory Th40 cells from MS patients produce IFNγ and IL-17 (Fig. 8A and B). Lymphocytes from MS subjects were isolated and were gated on CD4 and CD45RO then further CD40 gated (Fig. 8A) and cytokine levels were determined by intracellular staining. A small portion (8.4% ± 4) of peripheral memory Th40 cells produced IFNγ alone (Fig. 8B). A substantial proportion (30% ± 10.6) produced IFNγ+ and IL-17+ and an equal proportion (39.4% ± 10) produced IL-17+ alone (Fig. 8). The IFNγ/IL17 double producers and the IL-17 only producers were significantly increased above IFNγ alone (Fig. 8B). Th40 cells from control, non-autoimmune, non-infected subjects did not produce either cytokine immediately ex vivo (data not shown). It should be noted that cells were classic memory phenotype and gated exclusively on the Th40 population. Cells were analyzed by intracellular staining, which means that the cells were primed to produce cytokines, but not necessarily activated to do so.

Figure 8. Memory phenotype Th40 cells from MS patients produce both IL-17 and IFNγ.

Total blood lymphocytes were stained and gated for CD4 and CD45RO expression to delineate memory cells. (A) Within that population Th40 cells were assayed for IFNγ and IL-17 production by intra-cellular staining. Levels of IL-17 and IFNγ were determined above isotype controls. Cells were examined immediately ex vivo. (B) Graph represents levels of IFNγ only, IL-17 only and IFNγ/IL17 double positive cells from 11 RRMS subjects. Statistics were done by ANOVA, Tukey comparison, using the Graph Pad Prism program.

Discussion

Multiple Sclerosis is a complicated, neurodegenerative disease with a yet undetermined etiology. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) indicate no neural associated genes but do indicate immune related genes (Hafler et al., 2007). Genes identified include HLA-DRB1*1501 (DR15), DR6 and DQ6 each located within major histocompatibility complex (MHC) gene sets, the IL-7 receptor (CD127) and IL-2 receptor genes (Hafler et al., 2007; Sawcer, 2008). IL-7 and IL-2 are critical cytokines in T cell development and interestingly CD127lo cells are associated with regulatory T cell (Treg) designation (Liu et al., 2006). HLA expression impacts T cell development thus GWAS points towards T cell abnormalities during MS. Epidemiological analysis convincingly show that some genetic factors and immune related systems are relevant but lack power to illuminate the extent to which these factors are involved in MS (Sawcer, 2008). Several different autoimmune diseases have been examined using GWAS and compared to each other as well as inflammatory non-chronic infectious disease. Rather than revealing significant differences as was expected, studies reveal significant similarities, the majority of which are immune related specifically involving T cells.

We identified a CD4+ T cell subset expressing the CD40 receptor and showed that those T cells directly impact autoimmune pathogenesis (Carter et al., 2012a; Siebert et al., 2008; Vaitaitis and Wagner Jr., 2010; Vaitaitis et al., 2010; Vaitaitis et al., 2003; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2008; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2010; Vaitaitis and Wagner, 2012; Wagner et al., 2002; Waid et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2004; Waid et al., 2007). Th40 cells passively transfer type 1 diabetes in mouse models but importantly are involved in human disease (Siebert et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2007). As autoimmunity develops, Th40 cells increase in percentage and increase in number systemically (Vaitaitis et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2002; Waid et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2004). We determined that Th40 cell levels do not wax and wane in T1D throughout the disease as other ‘activated’ cells e.g. HLA+, CD30+, CD25+, CD69+ or CD154+, do. In longitudinal studies in human T1D, Th40 cell levels are as high in subjects who were diagnosed greater than 45 years previously as to those who were diagnosed 2 weeks prior (Siebert et al., 2008; Waid et al., 2007). In human T1D studies the Th40 occurrence remains relatively close to the disease associated mean, however in MS subjects Th40 cell levels varied a great deal relative to the mean. The majority of subjects examined were RRMS thus the variance in Th40 cell levels may reflect the relapsing/remitting nature of the disease. In fact RRMS subjects demonstrate wide Th40 variation while SPMS and PPMS have less variation. As we divided the MS samples into groups of different Th40 levels it became clear that some patients have a very high level of Th40 as well as a high intensity of CD40 expression on a per cell basis. Although we do not have the information available, it is possible that those patient samples were donated close to or during a relapse or while the patient was not undergoing any therapeutic treatments. It will be important to determine how this pathogenic T cell population is affected during the different phases of the disease as well as during therapeutic treatments to understand how to best control it.

Another interesting finding is that the Th40 to Treg ratio in MS is significantly lower than that in T1D but higher than the ratio in control subjects. These data highlight the importance of understanding commonalities in autoimmune disease while at the same time elucidating the differences. Perhaps therapeutic attempts should be targeted towards controlling the effector T cells more so than boosting Tregs in MS patients while T1D patients may benefit from doing both.

T cell activation requires two signals: 1) TCR mediated signal that leads to expression of activation molecules including CD69, CD25 and CD154 (Nyakeriga et al., 2012) and, 2) co-stimulus (Bretscher, 1992). In the case of autoimmunity TCR recognition of self-antigen would necessarily lead to expression of classic activation markers and once the antigen source is diminished, T cell activation should wane. In MS, CD69+ T cells return to levels close to that for non-autoimmune controls (Ichikawa et al., 1996), suggesting that early activation conditions diminish during disease. In this report we showed that a cohort of RRMS patients demonstrates TCR clonality within the Th40 cell populations and Th40 cells are responsive to MS associated antigens. Importantly Th40 cells are responsive to several different CNS antigens, suggesting a broad repertoire array localized within those T cells. Because of this diversity, Th40 cells would be primed to prolong pathogenesis and as shown here, likely through production of the inflammatory cytokines IFNγ and IL-17.

The data revealed that depending on HLA haplotype, individual MS subjects were responsive to different MS associated self-antigens, suggesting multiple pathways to disease onset. Also within any individual the same T cell subset could be responsive to different self-antigens. This poses a unique problem relative to therapeutic design. Copaxone is a hexamer peptide derived from the myelin basic protein (MBP) sequence that is commonly used to treat MS. Attempts for tolerance induction towards a single self-antigen may ultimately prove fruitless; given the overall plasticity of the immune system and now plasticity of individual immune responses in MS. A critical element here is epitope spreading, which has been established in EAE, the mouse model of MS (McMahon et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2007; O'Connor et al., 2005; Smith and Miller, 2006). If pathogenic effector cells can respond to a wide range of self-antigens, then pinning down a single antigen would prove very difficult. Alternative approaches to tolerance induction in MS now include multiple antigen treatments. In a human trial study of MS patients, an infusion of autologous blood mononuclear cells that were chemically coupled to 7 different MS associated peptides including MOG35 and MBP83, which were used in this study, demonstrated a decrease in antigen specific T cell responses (Lutterotti et al., 2013). This is encouraging but autoimmunity will likely require a multi-faceted treatment approach. By identifying a biomarker, in this case CD40, which is associated with long-term pathogenic T cells and specifically respond to MOG35 and MBP83, among other antigens, a new approach to tolerance emerges; inducing anergy directly through CD40 blockade. Previous attempts at universal pathogenic T cell control have focused on controlling CD28 or T cell activation steps mediated by ZAP70. These attempts have not been successful. By considering the actions of CD40, specifically directed towards pathogenic T cells, controlling autoimmune inflammation may be possible.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

●

We describe CD40 as a T cell biomarker, defining Th40 cells, in MS

-

●

Th40 cells are significantly elevated regardless of HLA haplotype in MS

-

●

Th40 to Treg ratio is more predictive of autoimmunity than either subset alone

-

●

Th40 cells from each patient demonstrate unique CNS antigen signatures

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: This work was supported by grants to DHW from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation; NIH (R01 DK075013-05); the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests: DHW is Co-Founder, shareholder and Chief Scientific Officer of OpT-Mune, Inc. No other conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- Anderson G, Rodriguez M. Multiple sclerosis, seizures, and antiepileptics: role of IL-18, IDO, melatonin. Eur J Neurol. 18:680–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini G, Morozzi G, Delfino L, Pera C, Falco M, Marcolongo R, Giannelli S, Ratti G, Ricci S, Fanetti G, et al. Analysis of HLA DP, DQ, and DR alleles in adult Italian rheumatoid arthritis patients. Hum Immunol. 1992;34:135–141. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(92)90039-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour N, Lapointe R, Saikali P, McCrea E, Regen T, Antel JP. A new clinically relevant approach to expand myelin specific T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2006;310:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RL, Wagner DH, Jr, Haskins K. CD40 on NOD CD4 T cells contributes to their activation and pathogenicity. J Autoimmun. 2008;31:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste EN, Nguyen VT, Wesemann DR. Molecular regulation of CD40 gene expression in macrophages and microglia. Brain Behav Immun. 2004;18:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher P. The two-signal model of lymphocyte activation twenty-one years later. Immunology Today. 1992;13:74–76. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90138-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Vaitaitis GM, Waid DM, Wagner DH. CD40 engagement of CD4(+) CD40(+) T cells in a neo-self antigen disease model ablates CTLA-4 expression and indirectly impacts tolerance. Eur J Immunol. 2012a;42:424–435. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J, Vaitaitis GM, Waid DM, Wagner DH., Jr CD40 engagement of CD4+ CD40+ T cells in a neo-self antigen disease model ablates CTLA-4 expression and indirectly impacts tolerance. Eur J Immunol. 2012b;42:424–435. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisniku LK, Brex PA, Altmann DR, Miszkiel KA, Benton CE, Lanyon R, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. Disability and T2 MRI lesions: a 20-year follow-up of patients with relapse onset of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2008;131:808–817. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of Sjogren's syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8:438–445. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girvin AM, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. CD40/CD40L interaction is essential for the induction of EAE in the absence of CD28-mediated co-stimulation. J Autoimmun. 2002;18:83–94. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani F, Hader W, Yong VW. Minocycline attenuates T cell and microglia activity to impair cytokine production in T cell-microglia interaction. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:135–143. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverman J, Woods A, Larson L, Weiner LP, Hood L, Zaller DM. Transgenic mice that express a myelin basic protein-specific T cell receptor develop spontaneous autoimmunity. Cell. 1993;72:551–560. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JJ, Allie SR, Mullen KM, Jones MV, Wang T, Krishnan C, Kaplin AI, Nath A, Kerr DA, Calabresi PA. Interleukin-17 in transverse myelitis and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;196:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory SG, Rioux JD, McCauley JL, Haines JL, Barcellos LF, Cree B, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington CJ, Paez A, Hunkapiller T, Mannikko V, Brabb T, Ahearn M, Beeson C, Goverman J. Differential tolerance is induced in T cells recognizing distinct epitopes of myelin basic protein. Immunity. 1998;8:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80562-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer B, Archelos JJ, Hartung HP. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:291–301. doi: 10.1038/nrn784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffjan S, Akkad DA. The genetics of multiple sclerosis: an update 2010. Mol Cell Probes. 2010;24:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby ES, Liggitt D, Brabb T, Schnabel B, Ohlen C, Goverman J. A pathogenic role for myelin-specific CD8(+) T cells in a model for multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:669–676. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Ota K, Iwata M. Increased Fas antigen on T cells in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1996;71:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics, C. Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory SG, Rioux JD, McCauley JL, Haines JL, Barcellos LF, Cree B, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent SC, Chen Y, Bregoli L, Clemmings SM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Hafler DA. Expanded T cells from pancreatic lymph nodes of type 1 diabetic subjects recognize an insulin epitope. Nature. 2005;435:224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature03625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, Gottlieb PA, Kapranov P, Gingeras TR, Fazekas de St Groth B, Clayberger C, Soper DM, Ziegler SF, Bluestone JA. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK. Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. A marker of activated/memory T cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:725–730. doi: 10.1172/JCI1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti CF, Popescu BF, Bunyan RF, Moll NM, Roemer SF, Lassmann H, Bruck W, Parisi JE, Scheithauer BW, Giannini C, Weigand SD, Mandrekar J, Ransohoff RM. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2188–2197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutterotti A, Yousef S, Sputtek A, Sturner KH, Stellmann JP, Breiden P, Reinhardt S, Schulze C, Bester M, Heesen C, Schippling S, Miller SD, Sospedra M, Martin R. Antigenspecific tolerance by autologous myelin peptide-coupled cells: a phase 1 trial in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:188ra175. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon EJ, Bailey SL, Castenada CV, Waldner H, Miller SD. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2005;11:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DH, Chard DT, Ciccarelli O. Clinically isolated syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:157–169. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DH, Grossman RI, Reingold SC, McFarland HF. The role of magnetic resonance techniques in understanding and managing multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 1):3–24. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SD, Katz-Levy Y, Neville KL, Vanderlugt CL. Virus-induced autoimmunity: epitope spreading to myelin autoepitopes in Theiler's virus infection of the central nervous system. Adv Virus Res. 2001;56:199–217. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(01)56008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SD, McMahon EJ, Schreiner B, Bailey SL. Antigen presentation in the CNS by myeloid dendritic cells drives progression of relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1103:179–191. doi: 10.1196/annals.1394.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyakeriga AM, Garg H, Joshi A. TCR-Induced T cell activation leads to simultaneous phosphorylation at Y505 and Y394 of p56(lck) residues. Cytometry A. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor KC, Appel H, Bregoli L, Call ME, Catz I, Chan JA, Moore NH, Warren KG, Wong SJ, Hafler DA, Wucherpfennig KW. Antibodies from inflamed central nervous system tissue recognize myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Immunol. 2005;175:1974–1982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, Fujihara K, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Montalban X, O'Connor P, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Waubant E, Weinshenker B, Wolinsky JS. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, Wolinsky JS, Reingold SC. Multiple sclerosis diagnostic criteria: three years later. Mult Scler. 2005;11:5–12. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1135oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S. The complex genetics of multiple sclerosis: pitfalls and prospects. Brain. 2008;131:3118–3131. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, Patsopoulos NA, Moutsianas L, Dilthey A, Su Z, Freeman C, Hunt SE, Edkins S, Gray E, Booth DR, Potter SC, Goris A, Band G, Oturai AB, Strange A, Saarela J, Bellenguez C, Fontaine B, Gillman M, Hemmer B, Gwilliam R, Zipp F, Jayakumar A, Martin R, Leslie S, Hawkins S, Giannoulatou E, D'Alfonso S, Blackburn H, Boneschi FM, Liddle J, Harbo HF, Perez ML, Spurkland A, Waller MJ, Mycko MP, Ricketts M, Comabella M, Hammond N, Kockum I, McCann OT, Ban M, Whittaker P, Kemppinen A, Weston P, Hawkins C, Widaa S, Zajicek J, Dronov S, Robertson N, Bumpstead SJ, Barcellos LF, Ravindrarajah R, Abraham R, Alfredsson L, Ardlie K, Aubin C, Baker A, Baker K, Baranzini SE, Bergamaschi L, Bergamaschi R, Bernstein A, Berthele A, Boggild M, Bradfield JP, Brassat D, Broadley SA, Buck D, Butzkueven H, Capra R, Carroll WM, Cavalla P, Celius EG, Cepok S, Chiavacci R, Clerget-Darpoux F, Clysters K, Comi G, Cossburn M, Cournu-Rebeix I, Cox MB, Cozen W, Cree BA, Cross AH, Cusi D, Daly MJ, Davis E, de Bakker PI, Debouverie M, D'Hooghe MB, Dixon K, Dobosi R, Dubois B, Ellinghaus D, Elovaara I, Esposito F, Fontenille C, Foote S, Franke A, Galimberti D, Ghezzi A, Glessner J, Gomez R, Gout O, Graham C, Grant SF, Guerini FR, Hakonarson H, Hall P, Hamsten A, Hartung HP, Heard RN, Heath S, Hobart J, Hoshi M, Infante-Duarte C, Ingram G, Ingram W, Islam T, Jagodic M, Kabesch M, Kermode AG, Kilpatrick TJ, Kim C, Klopp N, Koivisto K, Larsson M, Lathrop M, Lechner-Scott JS, Leone MA, Leppa V, Liljedahl U, Bomfim IL, Lincoln RR, Link J, Liu J, Lorentzen AR, Lupoli S, Macciardi F, Mack T, Marriott M, Martinelli V, Mason D, McCauley JL, Mentch F, Mero IL, Mihalova T, Montalban X, Mottershead J, Myhr KM, Naldi P, Ollier W, Page A, Palotie A, Pelletier J, Piccio L, Pickersgill T, Piehl F, Pobywajlo S, Quach HL, Ramsay PP, Reunanen M, Reynolds R, Rioux JD, Rodegher M, Roesner S, Rubio JP, Ruckert IM, Salvetti M, Salvi E, Santaniello A, Schaefer CA, Schreiber S, Schulze C, Scott RJ, Sellebjerg F, Selmaj KW, Sexton D, Shen L, Simms-Acuna B, Skidmore S, Sleiman PM, Smestad C, Sorensen PS, Sondergaard HB, Stankovich J, Strange RC, Sulonen AM, Sundqvist E, Syvanen AC, Taddeo F, Taylor B, Blackwell JM, Tienari P, Bramon E, Tourbah A, Brown MA, Tronczynska E, Casas JP, Tubridy N, Corvin A, Vickery J, Jankowski J, Villoslada P, Markus HS, Wang K, Mathew CG, Wason J, Palmer CN, Wichmann HE, Plomin R, Willoughby E, Rautanen A, Winkelmann J, Wittig M, Trembath RC, Yaouanq J, Viswanathan AC, Zhang H, Wood NW, Zuvich R, Deloukas P, Langford C, Duncanson A, Oksenberg JR, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL, Olsson T, Hillert J, Ivinson AJ, De Jager PL, Peltonen L, Stewart GJ, Hafler DA, Hauser SL, McVean G, Donnelly P, Compston A. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert JC, Inokuma M, Waid DM, Pennock ND, Vaitaitis GM, Disis ML, Dunne JF, Wagner DH, Jr, Maecker HT. An analytical workflow for investigating cytokine profiles. Cytometry A. 2008;73:289–298. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Miller SD. Multi-peptide coupled-cell tolerance ameliorates ongoing relapsing EAE associated with multiple pathogenic autoreactivities. J Autoimmun. 2006;27:218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck AK, Rewers MJ. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Clin Chem. 2011;57:176–185. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsby E, Ronningen KS. Particular HLA-DQ molecules play a dominant role in determining susceptibility or resistance to type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1993;36:371–377. doi: 10.1007/BF00402270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis G, Wagner DH., Jr CD40 Glycoforms and TNF-Receptors 1 and 2 in the Formation of CD40 ReceptoRs) in Autoimmunity. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:2303–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis G, Waid DM, Wagner D., Jr The Expanding Role of TNF-Receptor Super Family Member CD40 (tnfrsf5) in Autoimmune Disease: Focus on Th40 Cells. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Carter JR, Waid DM, Olmstead MH, Wagner DH., Jr An Alternative Role for Foxp3 As an Effector T Cell Regulator Controlled through CD40. J Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Poulin M, Sanderson RJ, Haskins K, Wagner DH., Jr Cutting edge: CD40-induced expression of recombination activating gene (RAG) 1 and RAG2: a mechanism for the generation of autoaggressive T cells in the periphery. J Immunol. 2003;170:3455–3459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Wagner DH., Jr High distribution of CD40 and TRAF2 in Th40 T cell rafts leads to preferential survival of this auto-aggressive population in autoimmunity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Wagner DH., Jr CD40 glycoforms and TNF-receptors 1 and 2 in the formation of CD40 receptoRs) in autoimmunity. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:2303–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Wagner DH., Jr Galectin-9 controls CD40 signaling through a Tim-3 independent mechanism and redirects the cytokine profile of pathogenic T cells in autoimmunity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitaitis GM, Wagner DH., Jr CD40 interacts directly with RAG1 and RAG2 in autoaggressive T cells and Fas prevents CD40 induced RAG expression. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:483–489. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DH, Jr, Vaitaitis G, Sanderson R, Poulin M, Dobbs C, Haskins K. Expression of CD40 identifies a unique pathogenic T cell population in type 1 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3782–3787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052247099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waid DM, Vaitaitis GM, Pennock ND, Wagner DH., Jr Disruption of the homeostatic balance between autoaggressive (CD4+CD40+) and regulatory (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) T cells promotes diabetes. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:431–439. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1207857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waid DM, Vaitaitis GM, Wagner DH., Jr Peripheral CD4loCD40+ auto-aggressive T cell expansion during insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1488–1497. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waid DM, Wagner RJ, Putnam A, Vaitaitis GM, Pennock ND, Calverley DC, Gottlieb P, Wagner DH., Jr A unique T cell subset described as CD4loCD40+ T cells (TCD40) in human type 1 diabetes. Clin Immunol. 2007;124:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wucherpfennig KW, Hafler DA. A review of T-cell receptors in multiple sclerosis: clonal expansion and persistence of human T-cells specific for an immunodominant myelin basic protein peptide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;756:241–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GX, Yu S, Gran B, Li J, Calida D, Ventura E, Chen X, Rostami A. T cell and antibody responses in remitting-relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in (C57BL/6 x SJL) F1 mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.