Abstract

Enamines and enamides are useful synthetic intermediates and common components of bioactive compounds. A new protocol for their direct synthesis by a net alkene C–H amination and allylic amination by using catalytic CuII in the presence of MnO2 is reported. Reactions between N-aryl sulfonamides and vinyl arenes furnish enamides, allylic amines, indoles, benzothiazine dioxides, and dibenzazepines directly and efficiently. Control experiments further showed that MnO2 alone can promote the reaction in the absence of a copper salt, albeit with lower efficiency. Mechanistic probes support the involvement of nitrogen-radical intermediates. This method is ideal for the synthesis of enamides from 1,1-disubstituted vinyl arenes, which are uncommon substrates in existing oxidative amination protocols.

Keywords: amination, copper, enamides, indoles, oxidation

Introduction

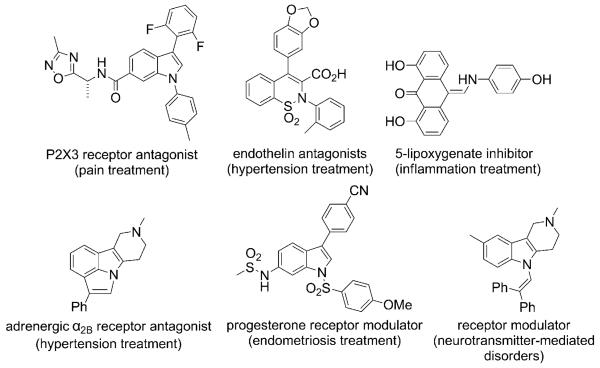

Compounds containing the enamine and enamide functionalities participate in diverse chemical reactions.[1] More stable enamines, which contain electron-withdrawing substituents or those that make up aromatic rings, are frequently found in biologically active compounds (e.g., Figure 1).[2]

Figure 1.

Representative bioactive enamines.

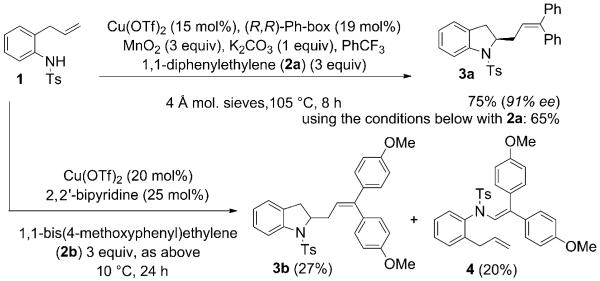

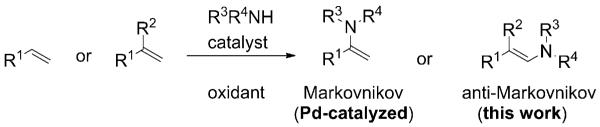

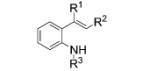

The synthesis of enamines by oxidative coupling of amines with alkenes appears straightforward and efficient (Scheme 1), but in practice, such direct couplings are surprisingly infrequently used, possibly because the scope of such methods is often limited to monosubstituted alkenes or acrylates.[3] Although the reactions with electron-deficient acrylates tend to favor the anti-Markovnikov product,[3a-c] reactions of terminal alkenes and vinylarenes are generally selective for the Markovnikov product (1,1-disubstitution).[3d-g]

Scheme 1.

Regioselectivity in alkene C–H aminations.

The metal-catalyzed oxidative-amination mechanism often involves aminometallation of the alkene,[3a-g] and steric hindrance on the alkene can impede reactivity. The synthesis of more highly substituted enamines thus often entails coupling the amine to more activated and synthetically advanced haloalkenes or vinylboronic acids.[4] We envisioned that the direct anti-Markovnikov oxidative coupling of vinyl arenes with amines could be accomplished through nitrogen-radical addition to the alkene followed by oxidation of the resulting radical to provide an enamine directly. Such a strategy would favor addition to 1,1-disubstituted alkenes to give 2,2-disubstituted-1-aminoalkenes. This kind of strategy has been recently demonstrated in limited scope for the Rucatalyzed synthesis of N-(4-methoxyphenyl)indoles via intramolecular oxidative amination[3p] and for the Ag-promoted synthesis of nitroalkenes via intermolecular oxidative couplings.[3h] Herein, we report a copper-catalyzed inter- and intramolecular coupling of a number of substituted anilines with various vinyl arenes for the efficient synthesis of N-aryl-β-aryl-enamides. Concurrently, we obtained intermolecular allylic amination products in the coupling reactions of substituted anilines with 1-alkyl-1-arylalkenes. We provide evidence for a mechanism involving nitrogen-radical addition to the alkenes (see below).

Results and Discussion

In recent years, our group has investigated the copper(II)-catalyzed intramolecular additions of amines to alkenes for the synthesis of functionalized nitrogen heterocycles.[5] In these reactions, a carbon-radical intermediate is formed and reacts with various radical acceptors, for example, diphenylethylene (DPE, 2a, Scheme 2).[5a] When 1,1-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)ethylene (p-MeO-DPE, 2b) was used, enamide 4, a net oxidative amination product, was formed competitively along with the expected indoline 3b (Scheme 2). We were both intrigued by the fact that enamide 4 is a net C–H amination product and by the possibility of developing an oxidative coupling reaction that was entirely intermolecular, even in the C–N alkene addition step.

Scheme 2.

Discovery of the copper-catalyzed C–H amination.

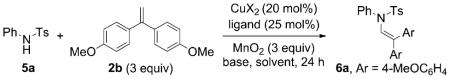

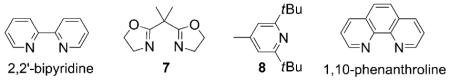

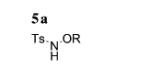

Our initial reaction optimization studies focused on the alkene C–H amination of N-tosylaniline 5a and 1,1-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)ethene (2b; Table 1). The initial trial used Cu(OTf)2 (30 mol%) with 2,2′-bipyridine as the ligand, MnO2 (3 equiv) as the stoichiometric oxidant, K2CO3 (1 equiv) as the base in CF3Ph at 120 °C for 24 h and gave a 65% conversion of 5a to 6a (Table 1, entry 1). A brief screen of copper salts revealed that Cu(OTf)2 (20 mol%) with bis(oxazoline) ligand 7 was superior to Cu(2-ethylhexanoate)2 and Cu(OTf)2·2,2′-bipyridine (Table 1, entries 1–4). We further determined that the reaction was as efficient in toluene, and base was unnecessary to obtain a 90% isolated yield of 6a (Table 1, compare entries 4 and 5). Reducing the copper loading to 15 mol% gave 80% conversion to 6a (Table 1, entry 6). The reaction was also run without oxidant with 50 mol% Cu(OTf)2·7 to determine if MnO2 was requisite for the reaction to proceed. The reaction went to 25% conversion, confirming that MnO2 makes the reaction more efficient (Table 1, entry 7). Continued screening revealed that the reaction could be run in dichloroethane at 105 °C with the addition of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (8) as the base, providing 6a in 85% isolated yield (Table 1, entries 8–10). Additionally, the reaction went to 20% conversion when only MnO2 was added (Table 1, entry 11). Therefore, MnO2 is capable of promoting this reaction, albeit less efficiently than when copper is present. In the absence of copper and MnO2, there was no reaction (Table 1, entry 12).

Table 1.

Oxidative amination optimization.[a]

| Entry | CuX2·ligand | Base | Solvent |

T [°C] |

Yield [%][b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cu(OTf)2·2,2’-bipyridine | K2CO3 | CF3Ph | 120 | 65 |

| 2 | Cu(eh)2 | K2CO3 | CF3Ph | 120 | 70 |

| 3[c] | Cu(eh)2 | K2CO3 | CF3Ph | 120 | 50 |

| 4 | Cu(OTf)2·7 | k2co3 | CF3Ph | 120 | 90[d] |

| 5 | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 90[d] |

| 6[e] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 80 |

| 7[f] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 25 |

| 8 | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | DCE | 105 | 65 |

| 9 | Cu(OTf)2·7 | k2co3 | DCE | 105 | 65 |

| 10 | Cu(OTf)2·7 | 8 | DCE | 105 | 85[d] |

| 11[g] | – | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 20 |

| 12[h] | – | – | CH3Ph | 120 | n.r. |

| 13[i] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 60 |

| 14[j] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 70 |

| 15[k] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 67 |

| 16 | Cu(0Tf)2·1,10-phenanthro- line |

– | CH3Ph | 120 | 85 |

| 17[l] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | 8 | DCE | 105 | 15 |

| 18[m] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | 50 |

| 19[n] | Cu(OTf)2·7 | – | CH3Ph | 120 | trace |

Conditions: Cu(X)2 (0.04 mmol) and ligand (0.05 mmol) in solvent (1 mL) were heated for 2 h at 60 °C under Ar. Sulfonamide 5a (0.20 mmol), MnO2 (0.60 mmol), solvent (1 mL), base (0.20 mmol), and flame-dried 4 Å molecular sieves (40 mg) were added. The solution was heated for 24 h in a sealed tube, then filtered through SiO2 and concentrated.

onversion [%] based on crude NMR analysis.

Used copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate [Cu(eh)2] (3 equiv) and no oxidant.

Isolated yield following flash chromatography on silica gel.

Run with 15 mol% Cu(OTf)2 and 18mol% 7.

Run with 50mol% Cu(OTf)2·7 in the absence of MnO2.

Run in then absence of a copper salt.

Run in the absence of MnO2 and CuX2.

Run with 2b (1 equiv).

Run with 2b (2 equiv).

Run with 2b (1 equiv), Cu(OTf)2 (30 mol%), and 7 (38 mol%). N.r. = no reaction.

O2 (1 atm, balloon) was used instead of MnO2.

Run with MnO2 (60 mol%) under O2 (1 atm, balloon).

Run with 60 mol% MnO2.

Although simple alkenes are readily available, other alkene substrates might not be. Therefore, we investigated lowering the loading of 2b. Use of one equivalent of 2b under the optimal conditions (Table 1, entry 5) gave a 60% conversion of 5a to 6a, whereas use of two equivalents of 2b gave a 70% conversion to 6a, indicating that the reaction will proceed substantially at lower alkene stoichiometry (Table 1, entries 13 and 14). Raising the catalyst loading to 30 mol% with one equivalent of alkene led to a marginal increase in yield (67% conversion, entry 15). We also found that the commercially available 1,10-phenanthroline ligand performs almost as well as the bis(oxazoline) ligand 7 and is superior to 2,2′-bipyridine (Table 1, compare entries 1, 4, and 5 to entry 16). The remainder of the material was starting 5a in entries 1–16 (Table 1).

An attempt to replace MnO2 with O2 (1 atm, balloon) led to only 15% conversion to 6a (Table 1, entry 17). Use of both O2 (1 atm) and substoichiometric MnO2 (0.6 equiv) led to 50% conversion to 6a, and significantly less conversion was observed without the O2 atmosphere under these conditions (Table 1, entries 18 and 19). Use of O2 as oxidant in different solvents often led to oxidation of the alkene to the corresponding ketone (see the Supporting Information for details). Other oxidants were screened, but none were as effective as MnO2 (see the Supporting Information for details).

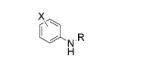

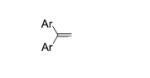

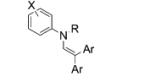

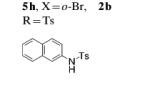

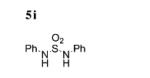

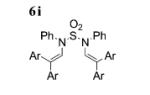

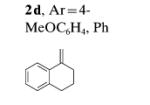

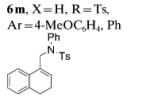

Following the optimized conditions A (Table 1, entry 5), a series of substituted N-sulfonylanilines underwent C–H amination coupling with 1,1-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)ethylene (2b) (Table 2). Different arylsulfonamides 5a-c reacted efficiently (Table 2, entries 1–3), whereas the 2-trimethylsilylethyl-sulfonylaniline reacted with somewhat lower efficiency (Table 2, entry 4). The reaction tolerates both electron-withdrawing, as well as electron-donating, substituents on the aniline ring with yields ranging from 60–84% (Table 2, entries 5–8). N-tosyl-2-naphthylamine undergoes C–H amination efficiently to give 6i in 85% yield (Table 2, entry 9). Sulfamide 5j underwent a double C–H amination to give enamide 6j, albeit in only 21% yield (Table 2, entry 10). After assessing the electronic effect of the aniline substrates, we turned to varying the nature of the alkene. An electronic trend emerged with regards to the nature of the alkene. Electron-rich 1,1-diaryl alkenes were higher yielding than electron-deficient 1,1-diaryl alkenes. When the alkene was changed from 2b (4-MeO-DPE) to 2a (DPE) to 2c (4-F-DPE), the yield of the enamide products drops from 90 to 60 to 32% for 6a, 6k and 6l, respectively (Table 2, entries 1, 11, and 12). At this juncture, it was unclear if the observed trend of decreasing yield with decreasing alkene electron density was the result of decreased reactivity in electrophilic addition of CuII or decreased reactivity with an electron-deficient nitrogen radical. Attempts to trap radical intermediates by adding (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) and 1,4-cyclohexadiene to the reaction mixture of 5a and 2b gave only 6a (reactions not shown). The unsymmetrical diaryl alkene 2d produced a 2:1 E/Z mixture of enamides 6m in 79% yield (Table 2, entry 13).

Table 2.

Scope of the oxidative and allylic amination coupling.[a]

| Entry | Amine | Alkene | Product | Yield [%][b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| 1 |

5a, X = H, R = Ts |

2b, Ar = 4- MeOC6H4 |

6a, X = H, R = Ts | 90 |

| 2 |

5b, X = H, R = PMBS |

2b | 6b, X = H, R = PMBS | 70 |

| 3 |

5c, X = H, R = Ns |

2b | 6c, X = H, R=Ns | 65 |

| 4 |

5d, X = H, R = SES |

2b | 6d, X = H, R = SES | 47 |

| 5 |

5e, X=p-F, R = Ts |

2b | 6e, X=p-F, R = Ts | 84 |

| 6 |

5f, X=p-OMe, R = Ts |

2b | 6f, X=p-OMe, R = Ts, | 67 |

| 7 |

5g, X=p- CF3, R = Ts |

2b | 6g, X=p-CF3, R = Ts, | 74 |

| 8 |

|

2b |

|

60 |

| 9 |

|

2b |

|

85 |

| 10 | 5j | 2b | 6j | 21 |

| 11 | 5a |

2a (DPE) Ar = Ph |

6k, X = H, R = Ts, Ar = Ph |

60 |

| 12 | 5a |

2c, Ar = 4- FC6H4 |

6l, X = H, R=Ts, Ar = 4-FC6H4 |

30 |

| 13 | 5a |

|

|

79[c] |

| 14 | 5a |

|

|

65 |

| 15 | 5a |

|

|

71 |

| 16 |

|

2g |

|

89 |

| 17 | 10 a, R = TBS | 2b | 11 | 53 |

| 18 |

10 b, R = butyl |

2b | 11 | 50[d] |

Conditions A, same as in Table 1 for entry 5.

Isolated yield.

A 2:1 mixture of alkene (E/Z) isomers was obtained.

Conversion (%, NMR). Ns = 4-nitrophenylsulfonyl, SES = 2-trimethylsilylethanesulfonyl, and PMBS = 4-methoxyphenylsulfonyl.

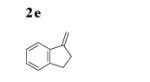

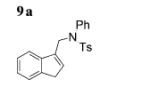

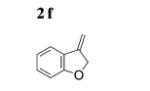

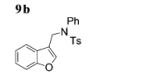

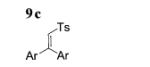

The scope of the alkenes was further extended to unsymmetrical 1,1-disubstituted alkenes, in which one of the substituents was an alkyl group. Phenylsulfonamide 5a underwent intermolecular alkene C–H amination with exocyclic alkene 2e. Interestingly, the major product 9a is the product of a net allylic C–H amination (Table 2, entry 14).[6] The scope was extended to alkenes 2 f and 2g, in which the allylic C–H amination products 9b and 9c were 3-substituted indene and benzofuran derivatives, respectively (Table 2, entries 15 and 16). In all three cases, the internal alkene product was exclusively observed.

Hydroxylamines 10a and 10b were also explored in this reaction (Table 2, entries 17 and 18). The isolated product from these reactions was vinylsulfone 11. We hypothesize that the hydroxylamines might degrade in situ to give sulfonyl radicals that add to the alkene intermolecularly. Addition of sulfonyl radicals to alkenes is known.[7] N-alkylsulfonamides and 1,1-dialkylalkenes do not participate in the intermolecular coupling reaction.[8,9]

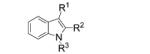

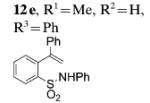

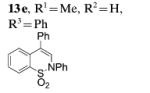

Next, we explored the intramolecular variation of the reaction for the synthesis of indoles (Table 3). When N-tosyl-2-vinylaniline 12a was submitted to the optimized reaction conditions A, indole 13a was formed in 66% yield. The reaction was extended to give N-tosyl-3-methylindole 13b, N-tosyl-3-phenylindole 13c, and N-tosyl-2-phenylindole 13d in moderate to high yields (Table 3, entries 2–5). We had established that MnO2 can partially facilitate the intermolecular C–H amination reactions (Table 1, entry 11). We reasoned the intramolecular nature of the indole-forming reaction should be more facile, so we probed the sole use of MnO2 as oxidant in this reaction as well. From this trial, we found that MnO2 promoted the reaction of 12c to an even greater conversion (70%), albeit still not as high as when CuII is present (Table 3, entry 4). This result prompted us to decrease the copper loading in this intramolecular reaction. The copper(II) loading was reduced to 5 mol% without loss of yield (Table 3, entries 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Synthesis of indoles and larger ring enamides.[a]

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield [%][b] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 1 | 12a, R1, R2 = H, R3 = Ts | 13 a, R1, R2 = H, R3 = Ts | 66 |

| 2[c] |

12b, R1 = Me, R2 = H, R3 = Ts |

13 b, R1 = Me, R2 = H, R3 = Ts |

90 |

| 3[c] |

12 c, R1 = Ph, R2 = H, R3 = Ts |

13 c, R1 = Ph, R2 = H, R3 = Ts |

97 |

| 4[d] | 12 c | 13 c | 70 |

| 5 |

12d, R1 = H, R2 = Ph, R3 = Ts |

13 d, R1 = H, R2 = Ph, R3 = Ts |

41 |

| 6[c] |

|

|

95 |

| 7[c] |

|

|

82 |

| 8 | 16 | 17 (unsaturated)/ | 94 |

| 18 (saturated) | (5:1) | ||

| 9[e] |

|

17 (exclusively) | 90 |

| 10 | 19 | n.r. |

Same conditions as in Table 1 for entry 5 were used, except no external alkene 2 was added.

Isolated yield.

Reaction run with 5 mol % Cu(OTf)2·7.

Reaction run in the absence of copper.

Reaction run in CF3Ph instead of CH3Ph.

We investigated the scope of the N-substitution in the intramolecular alkene C–H amination reaction. We found that the N-phenyl-(2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)aniline 12e reacted well in the intramolecular C–H amination reaction (Table 3, entry 6). Conversely, 2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)aniline, N-benzoyl-(2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)aniline, and N-Cbz-2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)aniline were unreactive under our C–H amination conditions (not shown).

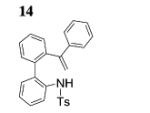

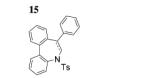

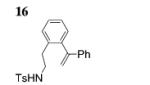

Next, we envisaged that larger cyclic enamides might be constructed using this oxidative alkene C–H amination. Synthesis of benzothiazine dioxide 15 from sulfonamide 14 occurred very efficiently, demonstrating a new and direct method for the synthesis of this medicinally important ring system (Table 3, entry 7).[2b] A seven-membered cyclic enamide would contain the core structure of dibenzazepines, a common motifs found in both natural products and pharmaceuticals.[10] The unsaturated dibenzazepine has been predicted to be aromatic and thus stable.[11] As illustrated in Table 3, when substrate 16 was submitted to the optimized reaction conditions A, cyclic enamide 17 was observed along with dibenzoazepine 18 (5:1 ratio) in 94% yield. The appearance of 18 seemed to indicate that a potential carbon radical intermediate was abstracting an H-atom from toluene, giving the saturated product. To probe this hypothesis, we ran the reaction in α,α,α-trifluorotoluene, eliminating the possibility of H-atom abstraction from solvent, and saw exclusively enamide product 17 (Table 3, entry 9). We also ran the reaction in α,α,α-trifluorotoluene with the addition of 1,4-cyclohexadiene, and 18 was again present in the crude reaction mixture along with starting sulfonamide and 17 (reaction not shown). These reactions provide evidence for a carbon radical intermediate and, by inference, a nitrogen radical intermediate.

We probed the use of the N-alkyl sulfonamide 19 in the intramolecular C–H amination (Table 3, entry 10) and found it to be unreactive under the reaction conditions. An N-(2-aryl)phenylsulfonamide previously shown to undergo Cu/PhI(OAc)2 promoted intramolecular aryl C–H amination also proved unreactive under our conditions.[12]

During this study, it became apparent that MnO2 can activate N-arylsulfonamides to undergo C–H amination of vinyl arenes to a certain extent. In point of fact, there are reports of MnO2 oxidizing anilines, and nitrogen-radical intermediates have been proposed in these instances.[13] The formation of nitrogen-radical intermediates under the conditions of our previously reported copper-catalyzed enantioselective alkene difunctionalization reactions (e.g., Scheme 1)[5] could lead to a “background” cyclization process. Such a background reaction could potentially erode reaction enantioselectivity levels (see the Supporting Information for an experimental examination and further discussion).

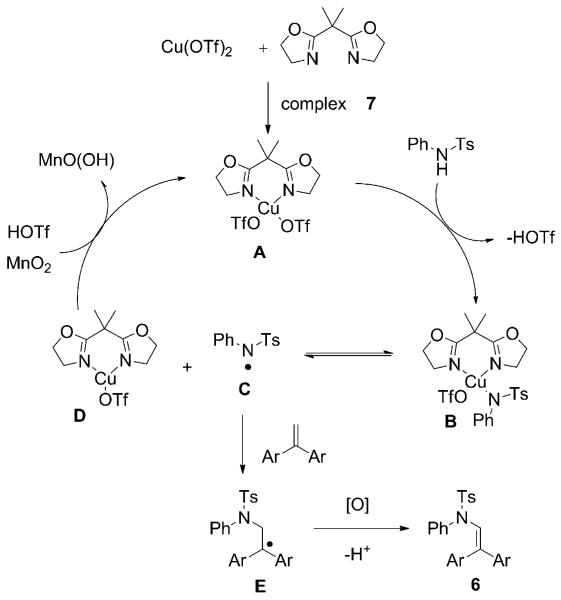

It is apparent that both copper and manganese complexes are promoting the reaction in a cooperative manner. One possible mechanistic pathway is shown in Scheme 3, in which copper is catalyzing the reaction and MnO2 is the stoichiometric oxidant. Another pathway, in which copper is not involved and MnO2 is oxidizing the amine that can subsequently add to the alkene, is also feasible. In the former scenario, complexation of Cu(OTf)2 with bis(oxazoline) 7 gives complex A. Ligand exchange with N-tosylaniline 5a gives complex B. When thermal energy is applied, the amino–copper(II) intermediate B[14] is in equilibrium with the nitrogen radical C and copper(I) complex D. If an excellent radical acceptor (e.g., 1,1-diarylalkene 2b) is present, the nitrogen radical can add to the alkene, generating intermediate E. Under oxidizing conditions, the benzylic radical is oxidized to the carbocation and elimination ensues to give C–H amination product 6, whereas the CuI complex D is oxidized back to CuII by MnO2.

Scheme 3.

Proposed copper-catalyzed oxidative amination mechanism.

Typically, nitrogen-centered radicals are generated from already functionalized amines,[15] such as aminohalides, that decompose in the presence of light or heat. In this case, the metals work in concert to oxidize the N-arylsulfonamide. Based on the reactive substrates in Tables 2 and 3 and the unreactive substrates (alkyl sulfonamides, see below), only aminyl radicals stabilized by two aryl substituents, or one aryl and one sulfonyl substituent, form to any extent in the reaction.[16k] N-Sulfonylhydroxylamines 10 also likely generate aminyl radicals that subsequently decompose to sulfonyl radical intermediates (Table 2, entries 16 and 17).

The pathway in which MnO2 is promoting the reaction independent of CuII involves the oxidation of the amine by MnO2. This oxidation is less common, but not unknown[13] and is thought to occur via one electron oxidation, perhaps associative. Thus, MnO2 can generate the aminyl radical, and the radical can then continue through the cycle as intermediate C in Scheme 3. Based on the optimization Table 1 trend, it appears that reactivity generally tracts with metal coordination ability in the order [Cu(bisoxazoline)](OTf)2>Cu(2-ethylhexanoate)2>MnO2. This supports an associative, inner-sphere amine-oxidation process.

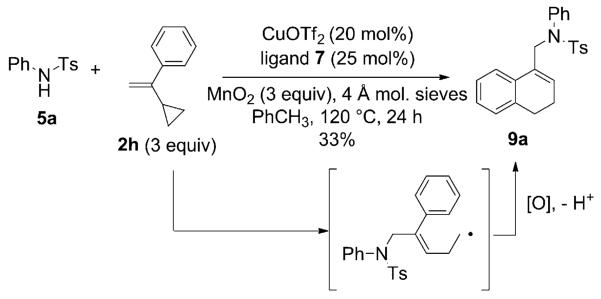

As a final probe of nitrogen radical reactivity, 1-(1-cyclopropylvinyl)benzene (2h) was subjected to the intermolecular C–H amination conditions (Eq. [1]).

|

(1) |

Allylic sulfonamide 9a was isolated as the major product in 33% yield. This product is likely the result of cyclopropane ring opening followed by intramolecular addition of the carbon radical to the phenyl ring.

Conclusion

This article discloses development of the first intermolecular copper-catalyzed alkene C–H/N–H oxidative coupling reaction.[3i,16,17] A number of enamides, allylic amines, and unsaturated nitrogen heterocycles can be formed by this relatively simple reaction. Nitrogen- and carbon-radical intermediates have been implicated in the reaction mechanism. Control experiments revealed that MnO2 can also promote these reactions, albeit less efficiently than when the copper(II) catalyst is present. The reaction is chemoselective, favoring reaction of amines and alkenes that can form stabilized radical intermediates. The C–H aminations reported herein use low-cost metal catalysts and oxidants, and the reaction mechanism is largely distinct from that of other alkene C–H amination processes, making it likely to serve as a complement to other reported procedures. The method for generation of nitrogen radicals described in this procedure, in general, appears to be more simple and safe than methods that use N-halogenated amines or peroxycarbamates and is complementary with respect to substrate scope to reactions involving other catalysts and promoters.[3,6] The nitrogen-radical-generating method disclosed herein could serve as inspiration for the rational design of additional coupling reactions.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of N-(2,2-Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)vinyl)-4-methyl-N-phenylbenzenesulfonamide (6a)

Conditions A: An oven-dried pressure tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar was put under an Ar atmosphere and charged with Cu(OTf)2 (15 mg, 0.0404 mmol), bis(oxazoline) 7 (9 mg, 0.0505 mmol), and CH3Ph (1 mL) and stirred at 60 °C for 2 h. The mixture was treated with N-phenyltosylamide 5a (50 mg, 0.202 mmol), MnO2 (53 mg, 0.606 mmol), 4-MeO-DPE 2b (146 mg, 0.606 mmol), and the remaining CH3Ph (1.02 mL, 0.1m). Molecular sieves (4 Å; 41 mg) were flame dried for 2 min and added directly to the reaction mixture. The pressure tube was purged with argon for 2 min, sealed, heated to 120 °C, and stirred for 24 h. Filtration of the cooled reaction mixture through a pad of SiO2 and subsequent evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave crude mixtures. Flash chromatography of the resulting crude mixture on silica gel (0–40% EtOAc in hexanes gradient) gave 6a (88 mg, 90%) as a light yellow solid. M.p. 130–131 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=7.51 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.02–6.99 (m, 3H), 6.85 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.80–6.78 (m, 5H), 6.63 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 2.44 ppm (s, 3H); 13C NMR (75 Hz, CDCl3): δ=159.5, 158.7, 143.8, 140.8, 137.5, 134.8, 133.2, 131.2, 130.2, 129.5, 128.9, 128.2, 127.8, 127.8, 126.6, 123.7, 113.6, 113.2, 55.3, 55.2, 21.6 ppm; IR (neat): , 2932, 2836, 1605, 1512, 1354, 1294, 1247, 1165, 1090, 1032, 814, 694 cm−1; HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+ C29H27O4NNaS: 508.1553, found: 508.1556.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Garrick Zebrig for Table 2, entry 3, and for exploring some less reactive substrates in the intermolecular C–H amination reaction. We thank the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS (GM-078383) for funding this research.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201301800.

References

- [1].For reviews, see: Carbery DR. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3455. doi: 10.1039/b809319a. Gopalaiah K, Kagan HB. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:4599. doi: 10.1021/cr100031f. for recent examples, see: Valenta P, Carroll PJ, Walsh PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14179. doi: 10.1021/ja105435y. Gigant N, Gillaizeau I. Org. Lett. 2012;14:3304. doi: 10.1021/ol301249n. Gigant N, Dequirez G, Retailleau P, Gillaizeau I, Dauban P. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:90. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102302. Pankajakshan S, Xu Y-H, Cheng JK, Low MT, Loh T-P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5701. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109247.

- [2].a) Müller K, Sellmer A, Prinz H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1997;32:895. [Google Scholar]; b) Bunker AM, Cheng X-M, Doherty AM, Edmunds JJ, Kanter GD, Lee C, Pepine JT, Skeean RW. US Patent 6545150 B2. Werner-Lambert Co.; Morris Plains (US): 2003. [Google Scholar]; c) Hung DT, Protter AA, Jain RP, Chakravarty S, Giorgetti M. International Patent WO 2010/051501 A1. Medivation Technologies, Inc.; San Francisco (US): 2010. [Google Scholar]; d) Protter AA, Chakravarty S. International Patent WO 2012/112961 A1. Medivation Technologies, Inc.; San Francisco (US): 2012. [Google Scholar]; e) Bleisch TJ, Clarke CA, Dodge JA, Jones SA, Lopez JE, Lugar CW, Muehl BS, Richardson TI, Yee YK, Yu K. International Patent WO 2007/087488 A2. Eli Lilly and Co.; Indianapolis (US): 2007. [Google Scholar]; f) Burgey CS, Crowley BM, Deng ZJ, Paone DV, Potteiger CM. International Patent WO 2010/111060 A1. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; Rahway (US): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [3].For intermolecular alkene C–H aminations: electron-deficient alkenes, see: Hosokawa T, Takano M, Kuroki Y, Murahashi S-I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6643. Bozell JJ, Hegedus LS. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:2561. Obora Y, Yosuke S, Ishii Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5058. doi: 10.1021/ol902052z. terminal alkenes and styrenes, see: Rogers MM, Kotov V, Chatwichien J, Stahl SS. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4331. doi: 10.1021/ol701903r. Brice JL, Harang JE, Timokhin VI, Anastasi NR, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2868. doi: 10.1021/ja0433020. Timokhin VI, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17888. doi: 10.1021/ja0562806. Timokhin VI, Anastasi NR, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12996. doi: 10.1021/ja0362149. Maity S, Manna S, Rana S, Naveen T, Mallick A, Maiti D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3355. doi: 10.1021/ja311942e. Intramolecular alkene C-H aminations: Harrington PJ, Hegedus LS. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:2657. Lu J, Jin Y, Liu H, Jiang Y, Fu H. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3694. doi: 10.1021/ol2013395. Larock RC, Hightower TR, Hasvold LA, Peterson KP. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:3584. doi: 10.1021/jo952088i. Izumi T, Nishimoto Y, Kohei K, Kasahara A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1990;27:1419. Heathcock CH, Stafford JA, Clark DL. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2575. Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Paladino G, Penoni A, Zoni C. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5627. doi: 10.1021/jo0495135. Tsvelikhovsky D, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14048. doi: 10.1021/ja107511g. Maity S, Zheng N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9562. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205137. Stokes BJ, Liu S, Driver TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4702. doi: 10.1021/ja111060q. Hsieh TH, Dong VM. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3062.

- [4].For enamines though Pd- and Cu-catalyzed coupling of amines with vinylhalides, see: Reviews: Dehli JR, Legros J, Bolm C. Chem. Commun. 2005:973. doi: 10.1039/b415954c. Tracey MR, Hsung RP, Antoline J, Kurtz KCM, Shen L, Slafer BW, Zhang Y. Sci. Synth. 2005;21:387. for selected recent methods, see: Venkat Reddy CR, Urgaonkar S, Verkade JG. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4427. doi: 10.1021/ol051612x. Jiang L, Job GE, Klapars A, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3667. doi: 10.1021/ol035355c. Hu T, Li C. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2035. doi: 10.1021/ol0505555. Selander N, Worrell BT, Chuprakov S, Velaparthi S, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14670. doi: 10.1021/ja3062453. for enamines through Cu-promoted coupling with amines and vinylboronic acids, see: Lam PYS, Vincent G, Bonne D, Clark CG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4927.

- [5].a) Liwosz TW, Chemler SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2020. doi: 10.1021/ja211272v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zeng W, Chemler SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12948. doi: 10.1021/ja0762240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chemler SR. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011;696:150. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Bovino MT, Chemler SR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3923. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Miller Y, Miao L, Hosseini AS, Chemler SR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12149. doi: 10.1021/ja3034075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Paderes MC, Keister JB, Chemler SR. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:506. doi: 10.1021/jo3023632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Turnpenny BW, Hyman KL, Chemler SR. Organometallics. 2012;31:7819. doi: 10.1021/om300744m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].For recent allylic amination examples, see: Kohmura Y, Kawasaki K, Katsuki T. Synlett. 1997:1456. Clark JS, Roche C. Chem. Commun. 2005:5175. doi: 10.1039/b509678b. Jiang C, Covell DJ, Stepan AF, Plummer MS, White MC. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1386. doi: 10.1021/ol300063t. Paradine SM, White MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2036. doi: 10.1021/ja211600g. Harvey ME, Musaev DG, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17207. doi: 10.1021/ja203576p. Lebel H, Spitz C, Leogane O, Trudel C, Parmentier M. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5460. doi: 10.1021/ol2021516. Yin G, Wu Y, Liu G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11978. doi: 10.1021/ja1030936. Reed SA, White MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3316. doi: 10.1021/ja710206u. Li Q, Yu Z-X. Angew. Chem. 2011;123:2192. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2144. Liang C, Robert-Peillard F, Fruit C, Muller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:4757. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4641. Lescot C, Darses B, Collet F, Retailleau P, Dauban P. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:7232. doi: 10.1021/jo301563j. Bao H, Tambar UK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:18495. doi: 10.1021/ja307851b. for metal-free allylic amination, see: Souto JA, Zian D, Muniz K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7242. doi: 10.1021/ja3013193.

- [7].Da Silva Correa CMM, Fleming MDCM, Oliveira MABCS, Garrido EMJ. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 1994:1993. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tosylamide, phthalimide, N-benzoyl tosylamide, and N,N-diphenylamine also failed to couple with 1,1-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)ethylene (2b).

- [9].Methylenecyclohexane failed to undergo the coupling reaction with PhNHTs (5a). Dihydropyran and 1,1,2-triphenylethylene also proved unreactive, whereas styrene and 1-phenyl-1,4-butadiene gave complex mixtures involving some olefin polymerization.

- [10].Liegeois J-F, Bruhwyler J, Rogister F, Delarge J. Current Med. Chem. 1995;1:471. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hess BA, Schaad LJ, Holyoke CW. Tetrahedron. 1972;28:3657. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cho SH, Yoon J, Chang S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5996. doi: 10.1021/ja111652v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].MnO2 has been used to oxidize anilines: Laha S, Luthy RG. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1990;24:363. Zhang H, Huang CH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:4474. doi: 10.1021/es048166d.

- [14].Paderes MC, Belding L, Fanovic B, Dudding T, Keister JB, Chemler SR. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:1711. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].For reactions of N-centered radicals, see: Fallis AG, Brinza IM. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:17543. Zard SZ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1603. doi: 10.1039/b613443m. Martinez E, Newcomb M. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:557. doi: 10.1021/jo051953o. Nicolaou KC, Baran PS, Zhong Y-L, Barluenga S, Hunt KW, Kranich R, Vega JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2233. doi: 10.1021/ja012126h. Aube J, Peng X, Wang Y, Takusagawa F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5466. Zhang H, Pu W, Xiong T, Li Y, Zhou X, Sun K, Liu Q, Zhang Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:2529. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209142. Creutz SE, Lotito KJ, Fu GC, Peters JC. Science. 2012;338:647. doi: 10.1126/science.1226458.

- [16].For copper-promoted or catalyzed intra- and intermolecular C-H/C-N oxidative couplings of amines with arenes or alkanes, see: Wang H, Wang Y, Peng C, Zhang J, Zhu Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13217. doi: 10.1021/ja1067993. Wang Q, Schreiber SL. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5178. doi: 10.1021/ol902079g. Inamoto K, Saito T, Hiroya K, Doi T. Synlett. 2008;20:3157. Wang X, Jin Y, Zhao Y, Zhu L, Fu H. Org. Lett. 2012;14:452. doi: 10.1021/ol202884z. Kawano T, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6900. doi: 10.1021/ja101939r. Lubriks D, Sokolovs I, Suna E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15436. doi: 10.1021/ja305574k. Qu G-R, Liang L, Niu H-Y, Rao W-H, Guo H-M, Fossey JS. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4494. doi: 10.1021/ol301848v. Michaudel Q, Thevenet D, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2547. doi: 10.1021/ja212020b. Brasche G, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:1958. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705420. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1932. Zhang GW, Zhao Y, Ge HB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:2559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209618. Huang PC, Parthasarathy K, Cheng C-H. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:459. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203859. Zhang L, Liu Z, Li H, Fang G, Barry B-D, Belay TA, Bi X, Liu Q. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6536. doi: 10.1021/ol2028288. Zhang L, Ang GY, Chiba S. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3682. doi: 10.1021/ol101490n. John A, Nicholas KM. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:4158. doi: 10.1021/jo200409h. Zhou W, Liu Y, Yang Y, Deng G-J. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10678. doi: 10.1039/c2cc35425j. Li Y, Xie Y, Zhang R, Jin K, Wang X, Duan C. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:5444. doi: 10.1021/jo200447x. Matsuda N, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. Org. Lett. 2011;13:2860. doi: 10.1021/ol200855t. Zhao H, Wang M, Su W, Hong M. Adv. Syn. Cat. 2010;352:1301. Gephart RT, Warren TH. Organometallics. 2012;31:7728.

- [17].For copper-catalyzed alkyne C–H aminations, see: Hamada T, Ye X, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:833. doi: 10.1021/ja077406x. Wang L, Huang H, Priebbenow DL, Pan F-F, Bolm C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3478. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209975.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.