Abstract

Objective

In January 2006 drug insurance coverage shifted from Medicaid to Medicare Part D private drug plans for the 6 million individuals enrolled in both programs. Beneficiaries faced new formularies and utilization management policies. It is uncertain if Part D, when compared to Medicaid, relaxed or tightened psychiatric medication management, which could affect receipt of recommended pharmacotherapy, and emergency department use related to treatment discontinuities. This study examined the impact of the transition from Medicaid to Part D on guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder and emergency department use.

Methods

Using interrupted time series and Medicaid and Medicare administrative data from 2004–2007, the authors analyzed the effect of the coverage transition on receipt of guideline-concordant anti-manic medication, guideline-discordant antidepressant monotherapy, and emergency department visits for a nationally-representative continuous cohort of 1,431 adults diagnosed with bipolar I disorder.

Results

Sixteen months after the transition, the proportion of the population with any recommended anti-manic use was an estimated 3.1 percentage points higher than expected controlling for baseline trends. The monthly proportion of beneficiaries with 7+ days of antidepressant monotherapy was 2.1 percentage points lower than expected. The number of emergency department visits per month increased by 19% immediately post-transition.

Conclusions

Increased receipt of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder may reflect relatively less restrictive management of anti-manic medications under Part D. The clinical significance of these changes is unclear given the small effect sizes. However, increased emergency department visits merit attention for the Medicaid beneficiaries who continue to transition to Part D.

INTRODUCTION

Insurance coverage for prescription drugs changed from state Medicaid programs to Medicare Part D plans on January 1, 2006 for all beneficiaries enrolled in both programs (“dual beneficiaries”). Among the most severely ill beneficiaries in the Medicaid and Medicare programs (1), one-third of dual beneficiaries aged 19 to 64 has been diagnosed with a serious mental illness (2, 3). Federal regulations required inclusion of most psychiatric medications on plan formularies and limited co-payment requirements for dual beneficiaries (4, 5). However, plans may apply utilization management policies to their formulary medications, including prior authorization and step therapy (in which a medication is available only after failure on a plan-preferred medication) (4). Among adults with bipolar disorder, change to more restrictive psychiatric drug utilization management has been significantly associated with reduced initiations and use of recommended pharmacotherapy (6, 7), and increased treatment discontinuation (6). Discontinued or delayed use of anti-manic medication is in turn associated with increased emergency department use (8) and health care costs (9). Medicaid programs have frequently applied prior authorization and other utilization management strategies to manage the use of antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, and antidepressant medications (10, 11). It is uncertain if, or to what extent, Part D plans’ utilization management policies relaxed or tightened psychiatric medication management relative to Medicaid programs.

The evidence on the effects of the transition from Medicaid to Medicare Part D coverage on dual beneficiaries’ receipt of medication for serious mental illness is limited to three observational studies that relied upon psychiatrist or patient self-report to define insurance status and/or prescription drug use. In a 2006 national survey, psychiatrists reported frequent problems with medication access among dual beneficiary patients during the first year of Part D implementation; however, no comparative information was available on patient experiences before the transition (12). Research that has compared psychiatric medication use before and after Part D implementation among dual beneficiaries found no change in patient self-reported use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications (13, 14), but the sample sizes were too small to construct diagnosis-based cohorts to assess psychiatric medication use relative to recommended use. No published research has assessed dual beneficiaries’ use of other health care services that may signal suboptimal pharmacotherapy for serious mental illness.

This quasi-experimental study evaluates the effects of the initial transition to Part D coverage on receipt of guideline concordant pharmacotherapy and emergency department use in the first two years following the implementation of Part D for a clinically defined cohort, dual beneficiaries diagnosed with bipolar I disorder.

METHODS

We used an interrupted time series design, the strongest quasi-experimental design, which requires a discrete intervention, a sufficient number of observation points before and after the intervention, and the absence of a concurrent event that might confound the intervention-outcome relationship (15). This design does not require the inclusion of patient covariates in the analytic model if the composition of the study population is stable, as it was in this study. The discrete intervention is the transition from Medicaid to Part D coverage on January 1, 2006.

The University of Wisconsin- Madison Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt (protocol 2012-0548).

DATA

We merged Medicaid enrollment, Medicare enrollment, and Medicare medical claims data for a five percent national random sample of Medicare beneficiaries from 2004–2007. For this sample, we additionally merged Medicare Part D claims data from 2006–2007 and pharmaceutical and medical claims data from 2004–2005 Medicaid Analytic Extract files (MAX). Enrollment files included dates of enrollment and beneficiary demographic information. To link data across programs, we matched social security number, name and date of birth. Medical claims included the service type, service dates, and diagnoses. Pharmacy claims included the product, fill date, and the number of days supply dispensed. These data have demonstrated reliability for research purposes (16–18). We excluded beneficiaries residing in Ohio and Louisiana due to data anomalies and in Arizona because all beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care.

SAMPLE

From an initial sample of 42,388 dual beneficiaries with at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar I, or bipolar II disorder, between 2004 and 2007, we excluded individuals with fewer than 10 months of continuous fee-for-service dual enrollment in each of the four years to eliminate the possibility that changes in population composition coincident with the Part D transition might bias our results. To ensure that individuals had prescription drug coverage in each year, we excluded beneficiaries who had no prescription drug claim from 2004–2007. Health care use data for managed care enrollees were not observable; thus we restricted the cohort to fee-for-service enrollees. Similarly, we excluded individuals with an institutional stay of more than 3 months since institutional prescription drug use data were not available. Serious mental illness is disproportionately represented in the nonelderly dual population (19). Thus, we excluded dual beneficiaries over the age of 65. Consistent with prior work, we required one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of bipolar disorder (i.e., ICD-9 codes 296.0x- 296.1x, 296.4x- 296.7x, 296.80 - 296.82, 296.89) on different dates of service with at least one of these diagnoses indicating bipolar I disorder (i.e., ICD-9 codes 296.0x - 296.1x, 296.4x - 296.7x) (20). We selected enrollees with a bipolar I diagnosis because it is the more severe form of bipolar disorder, and pharmacotherapy recommendations are more uniform and clear (21). We excluded beneficiaries with any diagnosis of schizophrenia. Finally, at least one bipolar disorder diagnosis must have occurred between January and June 2004 to increase the likelihood that bipolar disorder pharmacotherapy would have been appropriate for subjects in each month for which outcomes were assessed. The final analytic sample included 1431 adults.

OUTCOME MEASURES

Our measures of pharmacotherapy quality are derived from clinical practice guidelines (22, 23), and FDA indications. Recommendations for the acute and maintenance phases of bipolar I disorder include continuous treatment with one or more anti-manic agents (lithium; carbamazepine; divalproex sodium; lamotrigine; valproate sodium; valproic acid) or an antipsychotic medication. Therefore, we defined the receipt of these medications as indicators of recommended pharmacotherapy. For patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, antidepressant medication without a concurrent anti-manic medication is contraindicated, due to concerns that unopposed antidepressant treatment could worsen the course of bipolar disorder. Thus, our indicator of poor quality treatment is antidepressant monotherapy.

We constructed a binary indicator for receipt of any recommended anti-manic agent in a month. We used the medication possession ratio (MPR) to measure Part D-related changes in the level of concordance with evidence-based anti-manic pharmacotherapy (24). The MPR is the number of days of medication that a beneficiary has received divided by the number of days’ supply that they should have received if taking the medication as prescribed. We operationalized the recommendation for continuous anti-manic pharmacotherapy as the receipt of an anti-manic medication sufficient to cover at least 80% of days in a month (19, 25). We defined receipt of antidepressant monotherapy for 7 or more days in the month as a measure of poor quality. In usual care, there may be reasonable, brief delays in prescription fills, and several days of antidepressant monotherapy are unlikely to be of clinical significance.

For all pharmacotherapy measures, the numerator was defined using the prescription fill date and the days supplied. The days supplied of a medication were apportioned across months. The denominator includes the number of days in the month minus the number of days of residence in an acute inpatient facility, since inpatient medication is not ascertainable in claims data (19, 26). For overlapping fills, we treated drugs of the same generic name and the same NDC serially, and those with the same generic name and different NDCs concurrently. We treated overlapping fills for more than one generic drug name within the same drug class as concurrent fills.

Our secondary outcomes included the probability and count of emergency department visits for any cause. Additionally, we assessed emergency department visits related to a mental health or substance use disorder. An emergency department visit was considered related to a mental health or substance use disorder if the primary or secondary diagnosis on the claim indicated a behavioral health condition as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (i.e., ICD-9 codes 290.xx – 319.xx; 648.3x, 648.4x) (27). The denominator for all emergency department measures is the full analytic sample.

Independent variables included a “Part D” binary variable, set to one for the months following the implementation of Medicare Part D to estimate the potential immediate change in the outcome measure. A second variable, “time_after_Part D,” represented the number of months after Part D implementation to estimate potential change in trend.

ANALYSES

Our sample was defined in part by the presence of at least one bipolar diagnosis between January and June 2004, a diagnosis that was observable because the subject had a health care visit. Based on experience in other studies (6–8), we expected to observe some decrease in event rates after this diagnosis ascertainment period for outcomes that are dependent upon the occurrence of a visit (e.g., a prescription for an anti-manic medication) or that are themselves health care visits (i.e., emergency department use). These elevated rates naturally decline to the population’s underlying mean rate of use over time. We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the duration required to reach steady state by defining a sample that was identical to the study sample except for a later timing of the first observed diagnosis of bipolar disorder (July–December 2004), and assessing study outcomes both before and after the first observed bipolar disorder diagnosis. Based on these analyses, we excluded from our models the months during which we required a bipolar diagnosis (January–June 2004) and an additional 6 months (July–December 2004) to reach steady state.

We used segmented linear regression to estimate cohort-level changes in the outcomes from the pre-Part D period (January 2005–November 2005) to the post-Part D period (April 2006–December 2007). This approach estimates a slope for each of the time segments (pre and post-Part D). We began the Part D period in April 2006 because Part D plans were required to cover prescription fills for non-formulary medications through March 31, 2006. About two-thirds of states implemented some type of transitional drug coverage in January and February of 2006 for dual beneficiaries ranging from 1 to 6 weeks in duration (28). We excluded the four-month “phase-in” period from December 2005 to March 2006 from our regression models.

The unit of analysis was the person-month. All regression models controlled for a first order autoregressive correlation structure. From the regression results, we estimated the predicted value of each outcome and its 95% confidence interval (29) for April 2007, 12 months after the “phase-in” period. Regression results presented were significant at p < 0.05 unless otherwise stated. We used two-tailed statistical tests throughout and conducted analyses using Stata 12.

RESULTS

BASELINE DESCRIPTIVE CHARACTERISTICS

Overall, the majority of the sample was female. Approximately 66% ± 1 of beneficiaries were between the ages of 35–54, and a large majority was white (89%± 1). The average percentage of beneficiaries who had the recommended anti-manic medication available each month was 72% ± <1 while an average of 62% ± <1 of beneficiaries had a medication possession ratio (MPR) of at least 80% ± <1. The mean percentage receiving antidepressant monotherapy for 7 or more days per month was 17% ± <1. An average of 12% ± <1 of beneficiaries had an emergency department visit each month while the mean monthly number of visits among all sample members was .16 ± <1. Roughly 6% ± <1 of beneficiaries per month had an emergency department visit with a primary or secondary mental health or substance use diagnosis, and the mean monthly number of such visits was .07 ± <1.

TIME-SERIES REGRESSION RESULTS

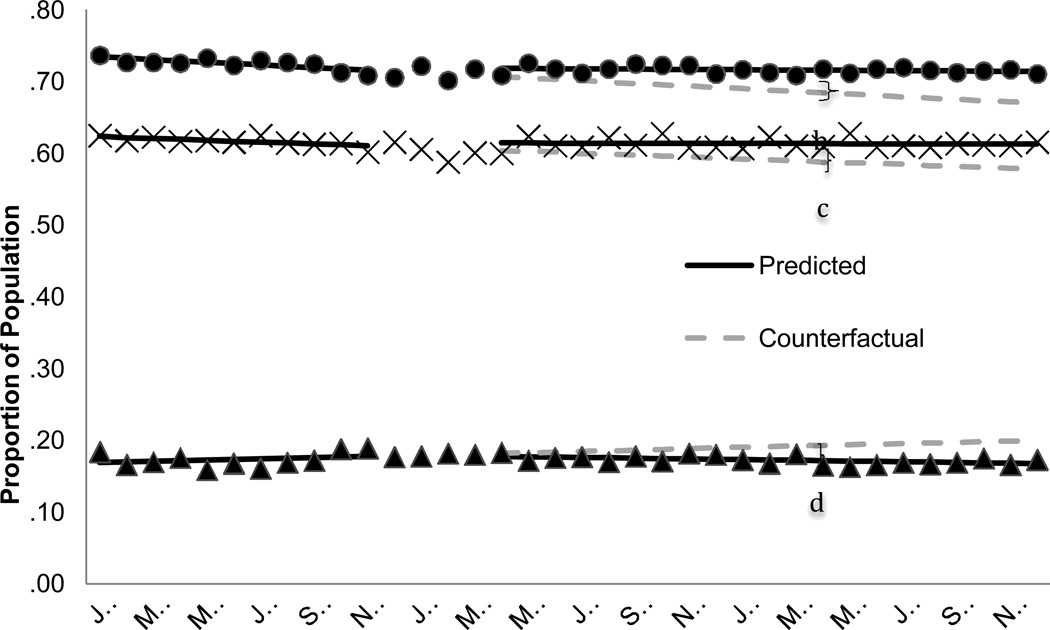

By April 2007, the mean proportion of the population with any recommended anti-manic use was an estimated 3.1 percentage points higher than expected in the absence of Part D (Figure 1 and Table 2) for a relative increase of 4.6%. The mean monthly proportion of the population that had an MPR of 80% for a recommended anti-manic medication was declining prior to Part D. Following the transition, this declining trend leveled off, resulting by April 2007 in a marginally significant 2.5 absolute percentage point increase [p = .06] in the mean proportion of the population with an 80% MPR. The predicted proportion of beneficiaries with 7 or more days of antidepressant monotherapy was an estimated 2.1 percentage points lower in April 2007 than expected in the absence of Part D [p = .06], which translates to an 11% relative decrease.

FIGURE 1. Guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder received among dual beneficiaries with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, 2005–2007a.

Abbreviation: MPR = Medication possession ratio

a The predicted line reflects the regression results for each segment. The counterfactual line continues the pre-Part D trend illustrating the expected trend in the absence of Part D.

The shaded area, December 2005-March 2006, represents the Part D phase-in period. These data points are not included in the regression model.

b Difference of 4.6%, p = .003

c Difference of 4.25%, p = .07

d Difference of −10.96%, p = .04

Table 2.

Regression results for receipt of guideline concordant pharmacotherapy and emegency department visits among dual beneficiaries with bipolar I disorder, 2005–2007

| Intercept | Baseline Trend | Part D | Trend Change Post Part D | Absolute Attributable Difference April 2007 |

Relative Attributable Difference April 2007 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| % Point | % Change | |||||||||||

| Guideline-recommended antimanic use in month | ||||||||||||

| Any | 73.64 | 72.90 to 74.39 | −0.18 | −.28 to −.09 | 0.51 | −.19 to 1.22 | 0.16 | .06 to .27 | 3.13 | 1.13 to 5.14 | 4.58 | 1.52 to 7.64 |

| MPR of 80% | 62.49 | 6 1 . 46 to 63.52 | −0.13 | −.26 to <1 | 0.57 | −.20 to 1.35 | 0.12 | −.01 to .26 | 2.50 | −.10 to 5.10 | 4.25 | −.35 to 8.85 |

| Antidepressant monotherapy use in month | ||||||||||||

| ≥7 days | 16.79 | 16.16 to 17.42 | 0.09 | −.01 to .18 | 0.09 | −1.30 to 1.47 | −0.14 | −.26 to −.01 | −2.11 | −4.31 to .09 | −10.96 | −21.28 to −.74 |

| Emergency department use in month | ||||||||||||

| % Point | % Change | |||||||||||

| Any visit | 11.92 | 10.28 to 13.57 | −0.02 | −.22 to .19 | 1.18 | −.83 to 3.20 | −0.04 | −.27 to .18 | 0.49 | −3.79 to 4.77 | 4.26 | −34.58 to 43.11 |

| Any visit with MHSUD diagnosis | 5.49 | 5.01 to 5.97 | 0.04 | −.05 to .13 | 0.53 | −.36 to 1.42 | −0.06 | −.16 to .04 | −0.44 | −2.62 to 1.75 | −6.55 | −37.32 to 24.21 |

| # Visits | % Change | |||||||||||

| Number of visits | 0.16 | .14 to .18 | −0.0006 | −.0039 to .0027 | 0.03 | >0 to .06 | −0.0004 | −.0039 to .0030 | 0.02 | −.05 to .10 | 16.42 | −41.43 to 74.27 |

| Number of visits with MHSUD diagnosis | 0.07 | .06 to .07 | 0.0004 | −.0006 to .0014 | 0.01 | >0 to .02 | −0.0009 | −.0019 to .0002 | −0.001 | −.02 to .02 | −1.66 | −31.01 to 27.69 |

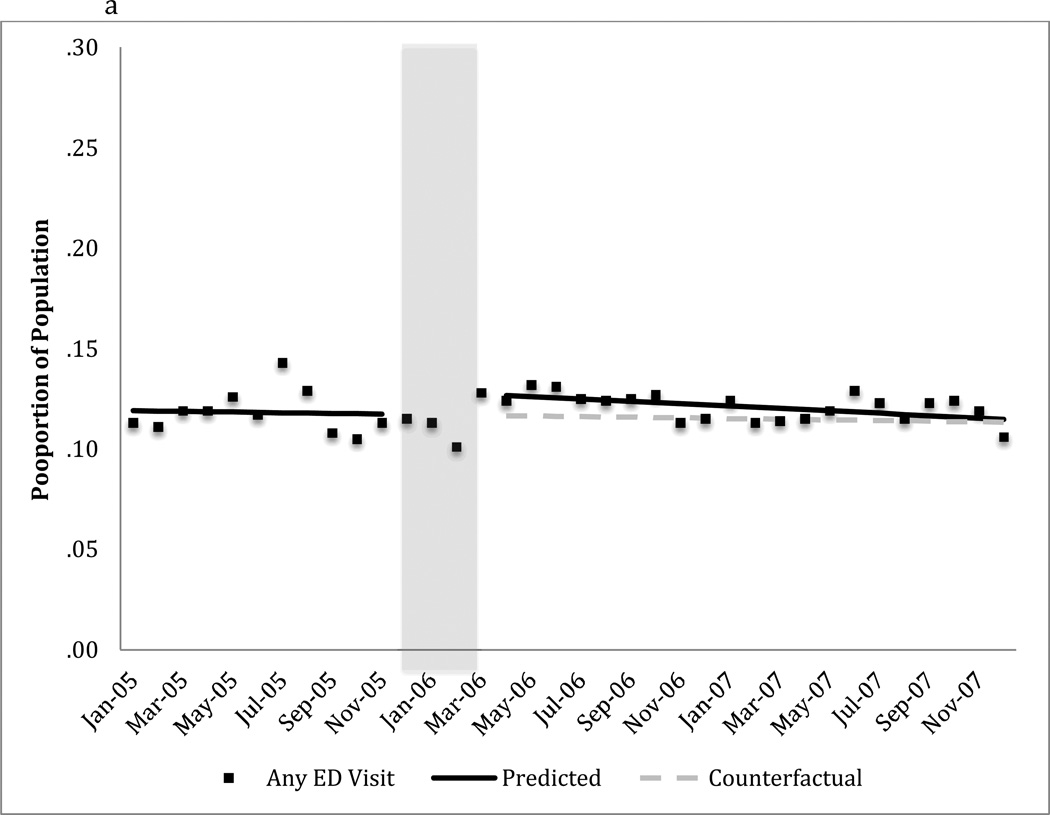

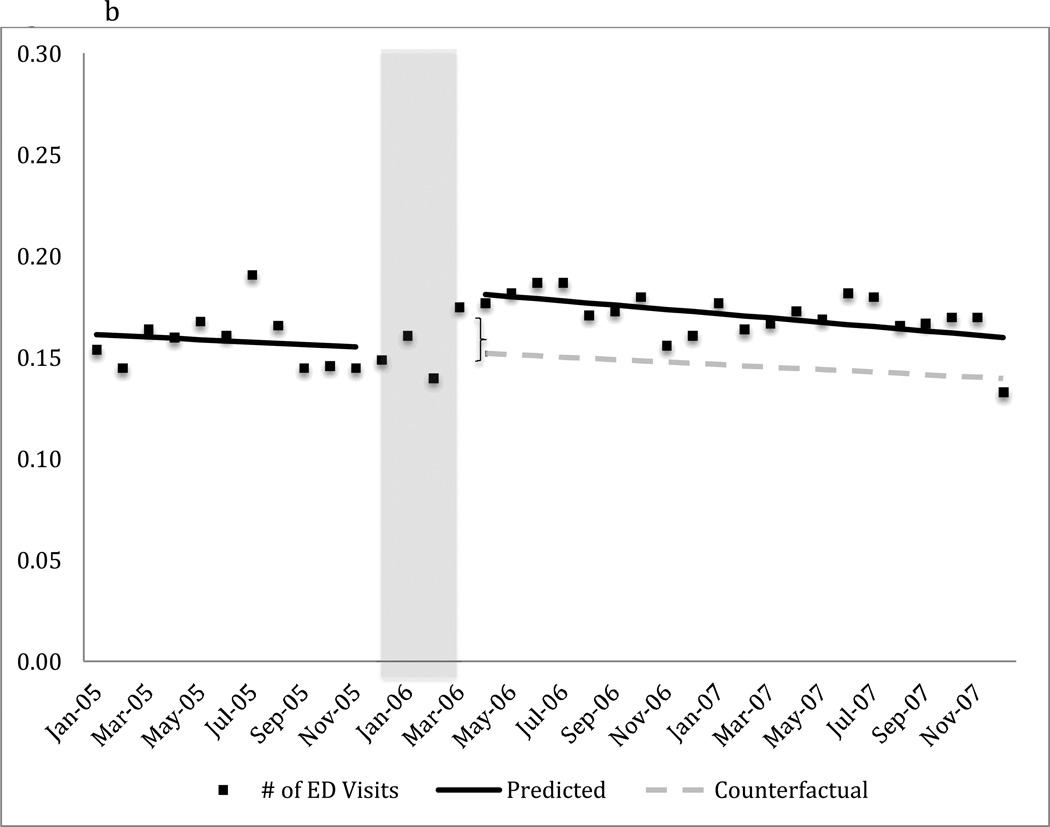

The transition to Part D coverage did not alter the probability of having any emergency department visit in the month (Figure 2a and Table 2). However, there was a 19% relative increase (.03 visits /.16 visits) in the mean number of monthly emergency department visits for any cause immediately following the transition to Part D coverage (Figure 2b and Table 2). The estimated difference between predicted and expected number of emergency department visits attributable to Part D as of April 2007 had very wide confidence intervals and was not statistically significant (Table 2).

FIGURE 2. Monthly emergency department use for any cause among dual beneficiaries with a diagnosis of bipolar I disordera.

a) Mean proportion of the population with any emergency department visit

b) Mean number of emergency department visits in the population

Abbreviation: ED = Emergency Department

a The predicted line reflects the regression results for each segment. The counterfactual line continues the pre-Part D trend illustrating the expected trend in the absence of Part D.

b Difference is 18.75% (i.e., .03/.16 visits), p < .05

The shaded area, December 2005-March 2006, represents the Part D phase-in period. These data points are not included in the regression model.

We also detected no change in the probability of having any emergency department visit related mental health or substance use (Table 2). We did, however, observe a 14% relative increase (.01 visits/ .07 visits) in the mean number of visits per month related to a mental health or substance use disorder (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the effects of the transition from Medicaid to Part D prescription drug coverage on receipt of recommended pharmacotherapy and emergency department visits among dually enrolled beneficiaries with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. There were two notable findings. The coverage transition did not adversely affect receipt of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy; rather, it was associated with very modest improvements. Second, although there was no significant change in the mean monthly rate of beneficiaries with any emergency department visit throughout the study period, there was an increase in the mean number of emergency department visits per month following the transition to Part D coverage.

The transition to Part D coverage flattened a previously declining trend in receipt of recommended anti-manic medication. The declining trend in anti-manic medication use before Part D implementation coincided with a period in which Medicaid programs increasingly used prior authorization to manage the use of anti-manic medications (10). The introduction of these state-level policies has been associated with relatively lower use of anti-manic medications (10). The observed decline in receipt of antidepressant monotherapy following the coverage transition might be explained by greater receipt of anti-manic medications due to relaxation of state policies targeting their use. Receipt of this contraindicated pharmacotherapy may partially result from limited access to recommended anti-manic medication rather than to patient or provider preference.

Our results for emergency department use suggest that visits increased only among a subset of beneficiaries who had at least one visit in the month. The estimated increase would equate to 43 additional ED visits per month from a baseline of 229 ED visits per month for this sample of 1431 beneficiaries until the immediate post-transition increase began to dissipate. This rise in visits may signal medication treatment discontinuity or drug- switching associated with the transition period. Although we did not observe a reduction in receipt of evidence-based pharmacotherapy coincident with the transition, our outcome measures were not sensitive to all types of treatment discontinuities including switching between medications and within-month treatment gaps. (8).

Medicaid beneficiaries continue to transition to Medicare and Part D prescription drug coverage each day. As soon as they become eligible for Medicare, beneficiaries are randomly assigned to a Part D plan. The experience of today’s “transitioners” may differ from that of the initial cohort studied here given subsequent program changes. The prevalence of utilization management requirements for psychiatric medications has increased among Medicare private drug plans (14). However, in 2008 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented a “grandfathering” provision that applies to the protected drug classes (e.g., antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, antidepressants). Plans may not implement prior authorization or step therapy requirements intended to steer beneficiaries to a new medication if they were already taking a drug within that class at the time of enrollment (5). Today, continuity and adequacy of pharmacotherapy for beneficiaries with bipolar I disorder transitioning to Part D may be determined in large part by their treatment history while under Medicaid drug coverage.

Our study aims to make inferences to the non-elderly adult dual beneficiary population with bipolar I disorder, individuals with different levels of severity, duration and phase of illness. We required continuous enrollment so our results may not generalize to less severely ill beneficiaries who exit the program. This research design allowed us to estimate the national average effect of the transition from Medicaid to Part D on study outcomes.. We could not identify the mechanism(s) within this transition that accounted for the observed effects. Medicaid programs and Medicare PDPs varied in their prescription drug coverage and management. Thus, our results may mask differences across states (given variation in Medicaid programs) and within states (given variation in PDPs). Finally, our measures of guideline concordance may conceal questionable quality practices (e.g., inappropriate polypharmacy) that are not discernable from claims data alone.

CONCLUSIONS

There was significant concern prior to the implementation of Part D regarding the potential effects of changing the drug coverage for dual beneficiaries with serious mental illness (4). We found that the likelihood of receiving evidence-based pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder did not decline; however, the immediate rise in emergency department visits among a subgroup of beneficiaries following transition requires further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of dual beneficiaries with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder

| N | % or Mean |

SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 503 | 35 | 1 |

| Age (%) | |||

| 20–34 | 247 | 17 | 1 |

| 35–44 | 440 | 31 | 1 |

| 45–54 | 516 | 36 | 1 |

| 55–64 | 228 | 16 | 1 |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 1268 | 89 | 1 |

| Black | 104 | 7 | 1 |

| Other | 59 | 4 | 1 |

| Average monthly guideline-concordant antimanic medication (%) | |||

| Any | 1,036 | 72 | <1 |

| Medication possession ratio of 80% or higher | 883 | 62 | <1 |

| Average monthly antidepressant monotherapy | |||

| 7 or more days | 248 | 17 | <1 |

| Average monthly emergency department use | |||

| Any ED visits (%) | 168 | 12 | <1 |

| Any visit with a mental health or substance use diagnosis (MHSUD) (%) | 82 | 6 | <1 |

| Number of visits | 229 | .16 | <1 |

| Number of visits with a mental health or substance use diagnosis | 100 | .07 | <1 |

| Unique Beneficiaries | 1,431 | ||

We required one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses of bipolar disorder on different dates of service with at least one of these diagnoses indicating BP1 and no diagnosis of schizohprenia to qualify for inclusion in the cohort. First observed BP Dx required between January–June 2004.

MHSUD refers to a primary or secondary diagnosis of ICD-9 codes 290.xx – 319.xx; 648.3x, or 648.4x

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following grant support: 1K01MH092338 from the National Institute of Mental Health; 1R01-HS018577-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality awarded to the Department of Population Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute where this study originated; a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research; 5R01AG032249 from the National Institute on Aging; and R01 MH084905 from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors has any affiliation, financial agreement, or other involvement with any company whose product figures prominently in the submitted manuscript.

An earlier version of this work was presented at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Annual Research Meeting, November 8–10, 2012, Baltimore, MD and the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, June 24, 2013, Baltimore MD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobson G, Neuman T, Damico A. Medicare's role for dual eligible beneficiaries. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. Available at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8138-02.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donohue J. Mental health in the Medicare part D drug benefit: A new regulatory model? Health Affairs. 2006;25:707–719. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Zhang N. Patterns of health care and disability for Medicare beneficiaries under 65. Inquiry. 2003;40:71–83. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Final Rule. Federal Register. 2005;70:4193–7585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2008. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual, Chapter 6. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Chapter6.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang YT, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Effects of prior authorization on medication discontinuation among Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:520–527. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Unintended impacts of a Medicaid prior authorization policy on access to medications for bipolar illness. Medical Care. 2010;48:4–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4c10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu CY, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Association between prior authorization for medications and health Service use by Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:186–193. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li JM, McCombs JS, Stimmel GL. Cost of treating bipolar disorder in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogt WB, Joyce G, Xia J, et al. Medicaid cost control measures aimed at second-generation antipsychotics led to less use of all antipsychotics. Health Affairs. 2011;30:2346–2354. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polinski JM, Wang PS, Fischer MA. Medicaid's prior authorization program and access to atypical antipsychotic medications. Health Affairs. 2007;26:750–760. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huskamp HA, West JC, Rae DS, et al. Part D and dually eligible patients with mental illness: medication access problems and use of intensive services. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1168–1173. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domino ME, Farley JF. Did Medicare Part D improve access to medications? Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:118–120. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Zuvekas SH. Dual eligibles with mental disorders and Medicare Part D: How are they faring? Health Affairs. 2009;28:746–759. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simoni-Wastila L, Ross-Degnan D, Mah C, et al. A retrospective data analysis of the impact of the New York triplicate prescription program on benzodiazepine use in Medicaid patients with chronic psychiatric and neurologic disorders. Clinical Therapeutics. 2004;26:322–336. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al. Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1992;43:69–71. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Adverse outcomes of underuse of beta-blockers in elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, et al. Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:855–863. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Neelon B, et al. Longitudinal racial/ethnic disparities in antimanic medication use in bipolar-I disorder. Medical Care. 2009;47:1217–1228. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181adcc4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision) - Introduction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:2–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschfeld RMA. Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Arlington, VA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Management of Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Washington, D.C: Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense; 2010. VA/DoD Clinical practice guideline for management of bipolar disorder in adults. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busch AB, Wilder CM, Van Dorn RA, et al. Changes in guideline-recommended medication possession after implementing Kendra's Law in New York. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:1000–1005. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, et al. Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al. Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care. 2002;40:630–639. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffey R, Houchens R, Chu B, et al. Emergency department use for mental and substance use disorders. Rockville, MD, U.S.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Available at http://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports/ED_Multivar_Rpt_Revision_Final072010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith V, Gifford K, Kramer S, et al. The transition of dual eligibles to Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage: State actions during implementation. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2006. Available at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7467.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang F, Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, et al. Methods for estimating confidence intervals in interrupted time series analyses of health interventions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.