Abstract

Two conferences, Creating More Compassionate Systems of Care (November 2012) and On Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: The Transformational Role of Compassion, Love and Forgiveness in Health Care (January 2013), were convened with the goals of reaching consensus on approaches to the integration of spirituality into health care structures at all levels and development of strategies to create more compassionate systems of care. The conferences built on the work of a 2009 consensus conference, Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care. Conference organizers in 2012 and 2013 aimed to identify consensus-derived care standards and recommendations for implementing them by building and expanding on the 2009 conference model of interprofessional spiritual care and its recommendations for palliative care. The 2013 conference built on the 2012 conference to produce a set of standards and recommended strategies for integrating spiritual care across the entire health care continuum, not just palliative care. Deliberations were based on evidence that spiritual care is a fundamental component of high-quality compassionate health care and it is most effective when it is recognized and reflected in the attitudes and actions of both patients and health care providers.

Introduction

Although the close connection between spirituality and health has been acknowledged for centuries, a strong emphasis on science in the practice of medicine over time has caused some to question or dismiss its potential therapeutic effects. By the early 1990s, however, hospitals and a variety of medical training programs began to recognize the role of spirituality in patient care, particularly in palliative care.1 Since that time, the professional literature reflects growing interest in and debate about this topic.2–6 Recent years have witnessed extensive growth in research on the ways in which spirituality can support health in the contexts of medicine, nursing, ethics, social work, and psychology. This has been especially true in the field of palliative care.7–9 Data indicate that a focus on spirituality improves patients' health outcomes, including quality of life.10–22 Conversely, negative spiritual and religious beliefs can cause distress and increase the burdens of illness.23,24

Given that global health outcomes are influenced by health care access, and considering increases in patient dissatisfaction and clinician burnout, addressing spirituality is both relevant and timely. Moreover, as the population ages worldwide, clinicians often feel ill equipped to be present to the suffering of patients and the overwhelmingly complicated medical and social issues associated with care for patients with complex chronic issues. Health care settings face challenges in providing compassionate care that focuses on honoring the dignity of each person.

Too often individuals visiting health care facilities are seen as a “disease that needs to be fixed” quickly and cheaply rather than as human beings with complex needs, including those of a spiritual nature. As a result, patients feel overwhelmed by the myriad tests and pharmaceuticals offered to them as “fixes” instead of having the opportunity to find their own inner resources of health and healing. In sum, they do not experience the care and compassion that relieves the burden and stress of illness—care they desire.25,26 For example, a large Canadian study reported that 96.8% of patients identified “receiving health care that is respectful and compassionate” as being very or extremely important.27

Palliative care, built on the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care, has long recognized the critical role of spirituality in the care of patients with complex, serious, and chronic illness.28 In 2004, the U.S. National Consensus Project developed eight required domains of care, among which spiritual, religious, and existential issues are included.29 Despite the comprehensive and practical orientation provided by these guidelines, clinicians still struggle with integrating spirituality into care. In response to this challenge, the Archstone Foundation sponsored a 2009 national consensus conference, Improving Quality Spiritual Care as a Domain of Palliative Care, convened by the City of Hope and George Washington Institute for Spiritual Health (GWish), focused on spiritual care as a component of high-quality health care and, more specifically, of palliative care. Participants from across the United States reached agreement on how spirituality can be applied to health care and made recommendations to encourage the delivery of effective spiritual care in the palliative care setting.30 Through a consensus process, participants developed the following definition of spirituality, intended to be broad and inclusive of religion:

Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.30

Participants also noted the critical role of spirituality in relationship-centered compassionate care, recognizing that health care professionals and patients enter into a professional relationship whereby each party is potentially transformed by the other in the context of what was described as a healing relationship—i.e., where patients in the presence of a compassionate clinician can find healing in the midst of their suffering.

Leveraging the work of the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care and the National Quality Forum's Voluntary Consensus Standards for Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care,31 the 2009 conference participants developed literature-based categories of spiritual care and recommended approaches to implementing these concepts in practice. Collectively, these recommendations became guidelines for improving the dimension of spiritual care in the palliative setting.30

The model and recommendations from the 2009 conference were well received in the United States and adopted by the National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Palliative and End-of-Life Care.31 Thus, by focusing on patient quality of life in the reality of their illness, health care institutions are working on quality improvements that begin to shift the focus of care from addressing only physical ailments of patients to whole person care. Nine hospitals in California have piloted these recommendations in palliative care settings.32 Health care professionals—including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, hospitalists, and educators—are being trained to integrate compassionate, relationship-centered care in their work settings by employing the interprofessional spiritual care model.

The United States National Consensus Conference on Creating More Compassionate Systems of Care

Building on the foundation of the 2009 conference, but expanding the focus beyond palliative care to health care in general, GWish, with the support of the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, led a National Consensus Conference on Creating Compassionate Systems of Care, held November 28 to 30, 2012. Conference participants (see Appendix 1) included a representative sample of 44 national experts from diverse professional backgrounds, including clinical research, palliative care, health economics, ethics, law, policy, insurance, workforce, and education. Participants gathered to bring their collective knowledge, wisdom, and passion for improving health care systems to discussions of strategies and standards for creating more compassionate systems of care through the integration of spirituality, in the broadest sense, at all levels of the health care system.

The conference focused on developing strategies to transform health care systems so that spirituality as related to health both in disease and wellness are integrated into activities focused on healing the whole person. Specific goals included the development of proposed standards of care, articulation of characteristics of a compassionate health system, and development of implementation strategies.

At the opening of the conference, participants reviewed and discussed models in which compassion is recognized as an aspect of spirituality. More specifically, a clinician's capacity to be compassionate is connected to his or her own inner spirituality or vocation. Compassion is an attitude, a way of approaching the needs of others and of helping others in their suffering. But more importantly, compassion is a spiritual practice, a way of being, a way of service to others, and an act of love. Thus, spirituality is intrinsically linked to compassion.33 Clinicians, by being aware of their own spirituality—including a sense of transcendence, meaning and purpose, call to service, connectedness to others, and transformation—are more able to be compassionate with their patients.

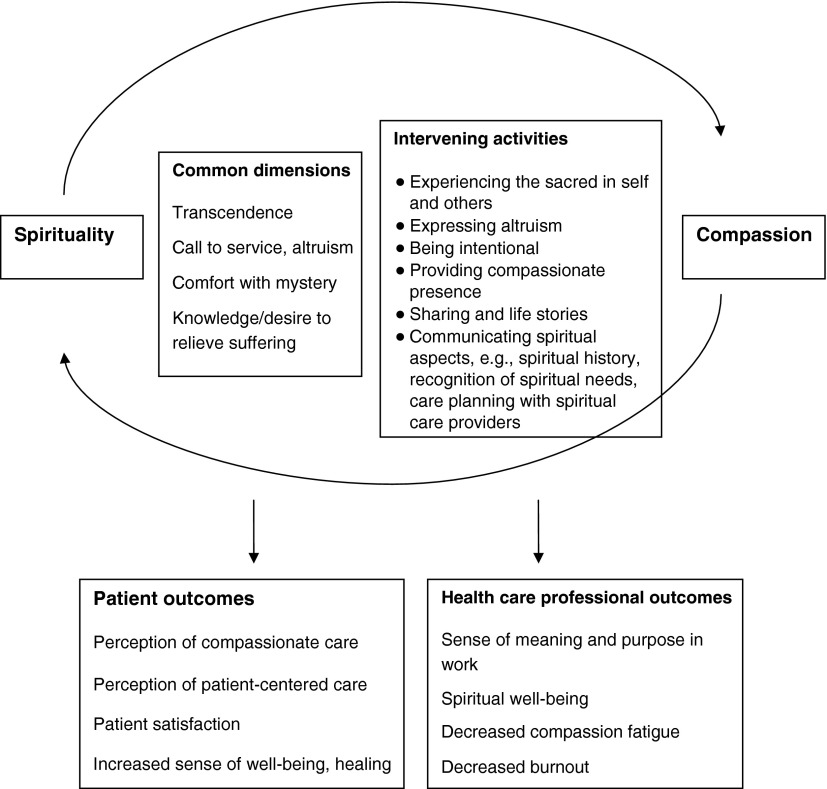

This concept is reflected in the model in Figure 1, depicting how spiritual care is entirely relationship based; therefore, the spirituality and health model informs compassionate care.34 Participants endorsed this model as one framework of compassionate care.

Fig. 1.

Model of spirituality and compassion.33

Conference participants also reviewed the model and recommendations from the 2009 conference and accepted the interprofessional spiritual care model as one that is practiced by a team, including trained chaplains. Participants initially vetted potential standards of care using an iterative Delphi process. Through a small group discussion process, participants developed and recommended new standards of care and voted on their top priorities. Those standards of care were further refined in a subsequent international meeting, as described below.

Beyond discussions of compassion and standards, participants also defined strategies in research, education, clinical practice, community engagement, policy, and communications that are required for the full integration of the proposed standards into health care. The recommendations for these strategies were further discussed at the international conference. The emerging overall recommendations are described below.

The 2013 International Conference on Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: The Transformational Role of Compassion, Love, and Forgiveness in Health Care

Rationale for an international conference

The strategies, recommendations, and interprofessional model of spiritual care developed by the 2009 conference participants resulted in unprecedented international impact that reached far beyond the field of palliative care, which was the discipline-based focus of the first conference. Health care practitioners and leaders are using the 2009 recommendations and care models as evidence of the need to integrate spirituality as an essential element of compassionate patient care and as the foundation for developing new care models across cultures and health care systems. At the George Washington University Summer Institute in Spirituality and Health, held each year since the 2009 conference, U.S. and international participants have expressed the desire to disseminate their knowledge in this field.

International activities and interest have increased over recent years with some nations and regions making efforts to define the role of spirituality in practice and policy.35 The European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), which has 52 associations in 31 countries, formed a task force to examine spiritual care. Its conference, held in October 2010, drew 14 people from 8 countries to begin forming a European consensus process to which 40 people are now contributing. EAPC created an inventory of European developments in this area and developed its own definition of spirituality (which draws from but also offered additional aspects to the definition devised during the 2012 U.S. conference):

Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant, and/or the sacred.36

Moreover, interest in caring for spiritual as well as physical and psychosocial needs throughout the countries of the European Union (EU) has resulted in a new EU Commission to investigate the role of spirituality in health care among EU nations. Several European colleagues of GWish convened a new EAPC task force in May 2011 to address the role of spirituality in palliative care. Using a consensus process, the EAPC task force is developing recommendations and strategies applicable to its members in 13 European countries. In addition, international organizations with a mission to improve health care throughout the world are independently developing policies and practices in the regions where they serve. While not always based on evidence or evaluated in a methodical manner, these efforts provide qualitative data that could inform a global discussion around spirituality and health care. Increasingly, however, evidence is accumulating through research to inform the integration of spirituality, particularly in palliative care, across many cultures.37–39

Results from the 2009 conference have also received traction at the international policy level. For example, representatives of the World Health Organization (WHO) Secretariat contacted GWish about using the 2009 conference recommendations and care models as the foundation for a discussion among leading organizations engaged in the advancement of global health policy and practices. Several meetings and planning sessions were held to develop a consensus conference designed to address the transformational role of spirituality in health care across religions, cultural traditions, and health care systems. Ultimately, the Fetzer Institute awarded GWish funds to support an international consensus conference.

Conference design and organization

GWish and Caritas Internationalis collaborated with the Fetzer Institute to convene a meeting January 13–16, 2013, in Geneva, Switzerland, the International Consensus Conference on Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: The Transformational Role of Compassion, Love, and Forgiveness in Health Care. Invitees included a representative sample of 41 international leaders, including physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, theologians, spiritual care professionals, donors, researchers, and policy makers (see Appendix 2). Three of these attendees were also participants in the U.S. conference in 2012.

During the 2013 conference, participants focused on the importance of understanding and empathizing with the diverse but often subtle cultural mores that influence spiritual beliefs and practices throughout the world. This conference was built on the same assumptions and background as the 2009 and 2012 conferences as well as on the importance of understanding and empathy. However, because participants came from all regions of the world, they were able to enrich the discussion with diverse cultural, ethnic, social, and spiritual perspectives.

Conference participants were charged with (1) identifying a multiculturally appropriate definition of spirituality within a health care context and (2) proposing consensus-driven standards of care to create whole person, compassionate health care systems through the integration of spirituality and health. Specifically, participants were asked to identify topics, circumstances, cultural mores, and other issues that affect the ability to include spirituality in health care settings across varied cultural settings. These perspectives greatly informed efforts to develop proposed standards of care and a broad framework for a strategic plan to improve the quality of spiritual care in health care in ways that are relevant to diverse cultures and geographic settings. The discussions also were organized to focus on required training in spiritual care; the role of spiritual leaders and health care professionals on interprofessional teams; policies, practice recommendations, and care models; and ways to increase the scientific rigor related to spirituality and spiritual care research and practice so that evidence is consistent across different settings and methods of implementation.

As with the 2012 U.S. conference, the international conference focused on developing strategies to transform health care systems through the integration of spirituality (broadly defined) and health in order to create more compassionate and holistic health settings. Specific goals were to (1) develop proposed standards of care, (2) articulate the characteristics of a compassionate health system, (3) identify barriers and assess opportunities, (4) develop recommendations and implementation strategies, (5) develop immediate and longer-term goals, and (6) create a coalition for change that would issue a call to action that could be used to encourage the development of health care systems that are spiritual and compassionate.

As was done in preparation for the previous conferences, participants engaged in an iterative, two-stage Delphi process. This approach employs consensus building group processes that bring together individuals with differing views in order to achieve consensus on difficult issues. This tool also facilitates groups in working through significant divergence of opinions, even on contentious issues.40

In the first round of the Delphi process, GWish leaders presented the recommendations derived from earlier collaboration with the Archstone Foundation, City of Hope, and the Fetzer Institute.30 Working with the recommendations and characteristics of a compassionate system developed in the previous processes, working groups ranked potential standards of care. All participants were then asked to:

• describe their experience of spirituality and compassion in clinical care;

• propose standards of care building on the prior consensus outcomes that might eventually be adopted nationally and by individual nations; and

• identify the most important next steps in research, education, clinical care, policy, community engagement, and communication.

The outcomes included a prioritized list of the top 20 recommendations from each group, which were given additional consideration at subsequent conferences. The second round of the Delphi process involved ranking of the importance of the proposed recommendations from the first round of this process. Participants also were asked to identify two or three key items to include in the domains of clinical research, education, clinical care, policy, community engagement, and communication.

Results of the Delphi process were then used to set the agenda for the conference and to create the postconference strategic plan. Notably, the Delphi process identified as a priority the need to emphasize community engagement and the necessity of developing strategies to educate providers about compassionate care.

Specific outcomes of the international conference were development of (1) an international consensus definition of spirituality in health care, (2) a set of proposed standards for implementing high-quality spiritual care in health care systems, and (3) a strategic plan for ongoing global consensus development and collaboration.

With regard to each of these activities, participants were invited to add any language or conceptual definitions related to their beliefs, country, or culture that should be given special consideration. Working sessions included an overview of current literature and approaches to the relationship between spirituality and health, discussions about multiculturally appropriate language related to spirituality, personal and patient experiences of spirituality, and WHO's definition of health and its relationship to spirituality.41

International Consensus Definition of Spirituality

During the international conference, participants noted that across a range of countries and cultures, different terms and language are often used to describe concepts, perceptions, and views related to spirituality. For example, although terms such as “history,” “transcendence,” and “sacred” were suggested as elements of spirituality, some participants objected to them because of their specific interpretations and meanings in their unique cultural contexts. Moreover, participants discussed the importance of family in many cultures and societies as an important aspect of spirituality, emphasizing the need to recognize the importance of family in any definition of spirituality. They asserted that in relation to health and well-being it is often the family and significant others that play the principal role in providing relationship and connectedness for patients.

Others pointed out the difficulty of viewing spirituality in strictly abstract terms, because it is not a product but an experience that emerges from engagement in life; it is a quality that is not simply produced but emerges over time. There was some debate about the complexity of the definition, with researchers hoping for a simplified statement that could be more amenable to research. But others felt strongly that the definition should be broad and inclusive of the many relationships and aspects of spirituality that can be found in different cultures and societies. Finally, unlike previous definitions, participants advocated for a sentence on how spirituality might be expressed. Beliefs, values, traditions, and practices have been shown to impact health and health care decisions.13,15,20 After a robust and dynamic discussion with several rounds of voting, agreement was reached on the following definition of spirituality:

“Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.”

Consensus Process for Developing Standards

Conference organizers initially anticipated that the 2012 and 2013 conferences would yield different recommendations. However, the respective meetings generated very similar proposals for standards and follow-up action. The combined and progressively refined set of recommendations is presented in Appendix 3.

These recommended standards reflect the strong consensus among participants in both the U.S. and international conferences that spiritual care is integral to compassionate care. The standards reflect a strong endorsement for education and training for all health care providers—from the clinicians who conduct screenings and take histories, to the aides who work with homebound patients, to the ward clerks who interact with families, staff and patients, and to the housekeeping staff who are often witness to the patients' cries of despair. The training should prepare staff to recognize and attend to the suffering of patients and families. Participants at both conferences strongly emphasized the need for spiritual care professionals, such as trained chaplains, as part of the interprofessional team. Recognition was given to the important role played by faith and other belief communities in the development of spiritual care models and in the delivery of ethically appropriate spiritual care.

Both conferences emphasized the need for respect when addressing spirituality of patients and families and urged that such conversations be person centered and conducted in an ethical manner. A broad definition of spirituality was unanimously recommended, so that as health care providers address spiritual issues with patients, they can remain alert to and hear whatever gives deep meaning to the patient, whether existential, religious, personal, or secular.

Finally, conference participants noted that spirituality and health is not just about disease and suffering. Spirituality is a fundamental aspect of health and wellness and thus an important aspect of preventative health. Participants called for the development of an evidence base for the impact of spirituality on health.

Call to Action for Compassionate Care

During the 2013 International Consensus Conference, participants also were asked to review a Call to Action that was developed by the Fetzer Institute's Health Advisory Council (see Appendix 4)42 and to discuss its relevance internationally. The purpose of the Call to Action was to start a platform from which to create a coalition to develop health care systems that are spiritual and compassionate. The group recognized this vision as an important foundational document that greatly informs its efforts to promote the inclusion of spirituality as an essential element in integrated and person-centered health care on a global scale (see Appendix 1).

Recommendations Emerging from the Conferences

Participants in each of the conferences presented above were asked to organize their specific recommendations around the six themes of (1) research, (2) clinical care, (3) education, (4) policy/advocacy, (5) communication, and (6) community involvement. Collective summaries appear below:

Research

To generate a scientifically robust evidence base, a research network should be established and linked to key researchers and existing networks. It should house a research database and provide a platform for exchange of evidence-based information, both online and face to face. A major goal of the network should be to establish a research agenda based on the priorities of clinicians, researchers, and patients. The agenda should recognize the importance of establishing the therapeutic effectiveness and cost effectiveness of spiritual care interventions. Several overarching frameworks were discussed, including a learning organization framework43 with the aim of evidence-based formation of clinicians and health systems/settings to promote health and reduce suffering.

Recommendations

1. Build research capacity and infrastructure, for example, through surveys, subjecting research proposals to peer review through the research network, and providing training on selection of research tools and methods.

2. Identify and obtain funding for multicenter and high-impact research (e.g., use the research network and small grants to fund small collaborative projects on which to build). Conduct multicenter research within a three-year period.

3. Study innovation pilots in spirituality and health.

4. Foster knowledge transfer, implementation, and dissemination of research results, in particular through peer-reviewed journals.

5. Link research to the goals of policy initiatives (e.g., the U.S. Affordable Care Act).

6. Consider plausible outcome measures for clinical research, such as staff retention, staff satisfaction, patient and family satisfaction, readmission, and resource utilization.

Clinical care

A critical first step in going forward is to arrive at a consensus definition of “spiritual care” by collecting and comparing definitions currently in use. Based on this collection and analysis a framework and models of care could be developed for use in different contexts and settings. Frameworks and models must recognize that providers cannot be made compassionate simply through the imposition of rules; methods are needed to achieve behavior change.

Recommendations

1. Identify best clinical practices, including the use of validation studies for clinical tools, use of health information technology, and use and applicability of quality indicators.

2. To better integrate spiritual care in clinical practice, develop spiritual screening history and assessment tools and protocols for training purposes and wide clinical use.

3. Make a business case for development and implementation of standards and tools. This could be accomplished through conducting demonstration projects that focus on, for example, readmission rates, patient satisfaction, and staff retention.

4. Plan long-term efforts to define and strengthen the role of professional spiritual care providers. This will require reliance on current practices and models, but also the development of competencies and role definitions for different settings.

5. Create and increase awareness of the importance of spiritual care among health care professionals through partnerships with education, communication, and policy activities.

Education

The audience for educational efforts is vast, including providers, accrediting and licensing bodies, regulators, patients, the general public, and policy makers. However, to achieve transformational change, evidence is needed, new relationships must be formed, measurable objectives must be developed, and new models of faculty development explored.

Recommendations

1. Develop competency standards, similar to the ones developed for U.S. medical education44 and the UK, for spiritual and religious care45 for health professionals that address attitudes, skills, and behaviors that facilitate achievement of consensus-based standards of care.

2. Create curricula that cover the definitions of spiritual care, self-awareness, cultural sensitivity, and assessment and skills.

3. Conduct research and assessment of the current body of knowledge to determine the adequacy of existing curricula and develop criteria for ongoing certification. Outcomes could include clinical performance, burnout, and meaning in the profession, with standards for vocational formation of clinicians.

4. Conduct a needs assessment to identify best and cost-effective training practices and to identify areas for further discussion and development.

5. Focus efforts on assessment of needed skill sets, which can inform curricula and training development.

6. Develop evaluation tools to accompany competency standards and report results as part of ongoing curriculum development processes.

7. Engage in public education, in particular at the policy level, to inform decision makers about the centrality of spirituality in health.

Policy/advocacy

The legislative, regulatory, financial, and administrative systems of respective countries create the environment that can either support or challenge the integration of spiritual care. For example, national health regulatory authorities can include spiritual care in performance assessment, accreditation, and licensing of health care institutions. Nongovernmental and private organizations, including faith-based organizations, can play a key role in collaborating with the government to strengthen spiritual care in the total health care of citizens.

Recommendations

1. Through national health systems, provide equitable, sustainable, and integrated care services to their citizens that include preventative, curative, rehabilitative, chronic, and palliative care and support. Evidence-based spiritual care should be integrated within these services.

2. Relying on educational institutions involved in health worker formation and training, undertake policy and operational research and training to build the evidence base for spiritual care.

3. Encourage WHO member states (1) to adopt a resolution within their respective regional WHO committees to promote strengthening spiritual care within national health systems; and (2) at the global level to adopt a World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution—as a follow-up to the 1984 WHA and the 1997 WHO executive board resolutions—mandating the WHO secretariat to undertake action in collaboration with interested parties to strengthen spiritual care as an integral component of health care.40,46

4. Create actionable and concrete standards that are effectively useful for accreditation and regulatory bodies.

5. Create a platform for the new movement in spirituality and health.

6. Encourage foundations and government and nongovernmental organizations to provide funding and support for initiatives in spiritual care.

Communication and dissemination

A communications plan should include efforts to research and clarify key messages for various audiences. It also should identify how to discuss broad and inclusive priorities; frame issues to change behavior and inspire people to feel, think, and do something differently; identify core problems and the potential impact of change; and reposition health care systems for solutions. Strategies could include identifying allies and opponents, taking action on “low hanging fruit,” delineating key messages that resonate among stakeholders, and developing advertising and business plans.

Recommendations

1. Establish in the short term an online community of researchers and providers.

2. Identify over the long term evidence-based best practices for broader dissemination, especially to policy makers.

3. Link communications efforts to the activities undertaken to develop research, clinical care, community engagement, policy and advocacy, and education.

Community engagement

Health care organizations can be thought of as communities as well as part of the communities they serve. A community engagement action plan should focus on understanding the demographic and cultural aspects of the communities that establish the foundation for implementing compassionate spiritual care. Plans should address the needs and sensitivities of the community and recognize the cultural, familial, and community compassionate care assets. Multisector stakeholders should be identified to develop strategies for assessing, addressing, and measuring community health and well-being. Finally, the capacity of community stewards should be bolstered to empower community members to engage fully in networks of relationships that foster well-being and healing neighborhoods and provide support and training for those providing and receiving care at home.

Recommendations

1. Develop a knowledge base of types and levels of community groups involved in spiritual care, including community mapping tools sensitive to context and a synthesis of existing evidence.

2. Determine the mode and level of engagement with spiritual care in health care (e.g., evaluate the needs, assets, and resources of communities, then analyze and disseminate the results at all levels).

3. Generate awareness of spiritual care in communities through a communications and marketing strategy involving dissemination, sharing, and branding.

4. Improve the capacity of communities to deliver and support spiritual care in health care.

Additional Recommendations and Themes

In addition to developing recommendations in these specific areas, participants identified several overarching issues that highlight the importance of cultural context in discussions about spirituality and compassionate care. Some participants agreed that the term “spirituality” is often conflated with religiosity, which can have negative connotations in some cultures because of perceived historical linkages between religion and repression. Moreover, spirituality is often linked with alternative or New Age thinking, which can cause some to dismiss its validity as a therapeutic agent or influence. At the same time, participants recognized that religious approaches to spirituality could strongly influence health care, especially in developing countries. Attendees of both conferences emphasized that spirituality should be defined broadly to be inclusive of religious, philosophical, existential, cultural, or personal beliefs, values, and practices and be centered on patient preferences. They also noted the importance of the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care and urged that health care settings focus on health and wellness, not only on disease.28

Participants also offered some observations about chaplains. Chaplains often are included as members of interprofessional teams practicing compassionate care, but not all cultures or countries recognize their role. Some might view their role as America-centric— they might suggest a type of authority not recognized by all. Logistically, many countries may not have the resources to train people to fill this role. It also was pointed out that chaplains are traditionally expected to perform religious services or offer types of guidance that are not always well integrated into the health care team. Chaplains may object to the fact that many health care providers are not trained to provide spiritual care and, therefore, maintain that health care providers should not be involved in delivery of such care. Although some health care providers may feel strongly that they are called to fulfill this role, others feel inadequately prepared for it. Chaplains can play a strong partnership role as integral, professional members of the health care team with their own domain of expertise in cultures where the role of chaplain exists.

Barriers to the implementation of spiritual care as a domain of health care include lack of training and concerns about proselytizing and coercion by providers. Some conferees said that formally recognized religious practitioners (e.g., priests, rabbis, nuns, imams), community elders, tribal chiefs and leaders, faith healers, shamans, and lay people such as nurses and gurus can be considered trusted members of the community for addressing spiritual care. Other participants reported that they have conducted workshops and training programs, created new organizations, and developed guidelines and competencies in spiritual care to promote the field. In the end, it was agreed that practitioners must be aware of their own sense of spirituality to be sensitive to such needs in others and that such sensitivity cannot be “taught” to everyone.

Both the United States and international conference participants emphasized the connection between health care settings and systems and the communities they serve and insisted that these entities should provide opportunities to develop and sustain a sense of connectedness with the community in which they serve. Examples include community nurses who serve in communities of their own faith and are able to connect more effectively with health care teams in clinical settings. In a similar way, health care settings could offer programs for homebound seniors or healthy food programs.

Finally, participants in both conferences emphasized the need for leadership to support spirituality and health as part of compassionate health systems. Attendees noted that organizational policies should promote and support spiritual compassionate care at the bedside, in the boardroom, and in staff relations, and noted the importance of spiritually centered, compassionate care across the spectrum from leadership to staff to patient and family. They emphasized the importance of pursuing all the areas of activity—research, education, clinical care, community engagement, communication, and policy—so that all levels of clinical care, from research through policy, are addressed by various populations.

Conclusions and Next Steps

These conferences provided opportunities to explore ways to operationalize spiritual care and create global guidelines for dissemination based on the experiences and expertise of a global community. Some general observations were made as well. Going forward, we need to consider multigenerational views of spirituality, avoid assuming that all spiritual care should be administered by professionals in this field, and take into account regional political and other historical contexts when considering the approaches to offering spiritual care. Participants in the 2013 conference concurred with the broad conclusions of the groups that preceded them: that health care models around the world must be transformed into systems that honor the dignity of all people (patients, families, and health care workers); that models should be focused on relationships with individuals as well as communities; and that compassion should be the driving outcome for any health delivery system.

Subsequent activities have focused on sustaining these efforts through the development of a Global Network in Spirituality and Health. The network will be coordinated by a core group facilitated by GWish and Caritas Internationalis, and will include participants from all previous conferences. The network will facilitate collaboration and share resources that can serve to implement the recommendations in Appendix 2. Activities will continue to be led by the chairs of the conference working groups in research, education, clinical care, policy, and community engagement. In addition, the Spirituality Online Education & Clinical and Resource Center (SOERCE) will develop an online learning community and share resources from the network.

What clearly emerged from both conferences was the recognition of a growing movement in spirituality and health, what some have called a silent revolution for creating more compassionate systems of care through the full integration of spirituality into health care.47 Participants expressed strong enthusiasm to create a platform for this movement, through excellence in research and clinical innovation, by focusing on spirituality in professional education as essential for the formation of spiritual/humanistic-scientific practitioners, and by engaging communities and policy makers in the creation of holistic healing centers of compassionate care.

As evidenced from the years of consensus building in spirituality and health and from the activities described here, there is a strong desire, nationally and globally, to integrate spirituality more fully into health systems. Consensus-derived potential standards of care and strategies to implement these standards as described in this paper are offered as an organizing framework for this endeavor. Research in this area is being conducted, and innovative clinical and educational models that include community involvement are being developed, in diverse clinical sites. Our further hope is that the potential standards outlined above will be strengthened, refined, and integrated into health policies. As echoed by all the participants in these meetings, full integration of spirituality into health care will result in more compassionate, person-centered health systems.

Appendix 1. Participants in 2012 National Consensus Conference on Creating Compassionate Health Care Systems

Jeffrey S. Akman, MD

Dean

School of Medicine and Health Sciences

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Tracy Balboni, MD, MPH

Associate Professor of Radiation Oncology

Harvard Medical School

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Boston, MA

Marc I. Barasch

Founder and Chief Executive Officer

Green World Campaign, Healing Path Media

Author, The Healing Path; Remarkable Recovery; The Compassionate Life

Boulder, CO

Nancy Berlinger, PhD

Research Scholar

The Hastings Center

Garrison, NY

Amy E. Butler, PhD

Executive Director

Foundation Relations

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Candice Chen, MD, MPH

Assistant Research Professor

School of Public Health and Health Services

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Heidi Christensen

Associate Director for Community Engagement

Center for Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships

Department of Health and Human Services

Washington, DC

Carolyn M. Clancy, MD

Director

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services

Washington, DC

Kathleen A. Curran, JD

Senior Director

Public Policy

Catholic Health Association of the United States

Washington, DC

Timothy Daaleman, DO, MPH

Professor & Vice Chair

Department of Family Medicine

University of North Carolina

Chapel Hill, NC

Catherine D. DeAngelis, MD, MPH

University Distinguished Service Professor, Emerita

Professor of Pediatrics, Emerita

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Professor of Health Policy and Management

School of Public Health

Editor in Chief Emerita, Journal of the American Medical Association

Baltimore, MD

Deborah Duran, PhD

Director

Strategic Planning, Legislation and Scientific Policy

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Allen R. Dyer, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Clese Erikson, MPA

Director

Center for Workforce Studies

Association of American Medical Colleges

Washington, DC

Chuck Fluharty, MDiv

President & Chief Executive Officer

Rural Policy Research Institute

Columbia, MO

Rosemary Gibson

Author, Wall of Silence

Section Editor, Archives of Internal Medicine

Arlington, VA

George Handzo, MDiv, BCC

Director of Health Services Research and Quality

HealthCare Chaplaincy

New York, NY

Susan House

Executive Director

Catholic Health Association of British Columbia

Burnaby, BC

David Hufford, PhD

Professor Emeritus of Humanities and Psychiatry

Penn State College of Medicine

Senior Fellow

Samueli Institute

Media, PA

Sharon K. Hull, MD, MPH

President

Metta Solutions, LLC

Medical Director

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Collaborative

Summa Health System

Professor

Department of Family and Community Medicine

Northeast Ohio Medical University

Cleveland, OH; Akron, OH

Tom A. Hutchinson, MD

Director

McGill Programs in Whole Person Care

Professor of Medicine

McGill University Centre for Medical Education

Montreal, QC

Cynda Hylton Rushton, PhD, RN, FAAN

Anne and George L. Bunting Professor of Clinical Ethics

Berman Institute of Bioethics/School of Nursing

Professor of Nursing and Pediatrics

Johns Hopkins University

Baltimore, MD

Carolyn Jacobs, MSW, PhD

Dean and Elizabeth Marting Treuhaft Professor

Smith College School of Social Work

Northampton, MA

Mark E. Jensen, PhD, MDiv

Teaching Professor of Pastoral Care and Pastoral Theology

Wake Forest University School of Divinity

Winston-Salem, NC

Jean Johnson, PhD, RN, FAAN

Senior Associate Dean for Health Sciences

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Robb Johnson, MPH, MPA

Associate Vice President of Special Projects

Fenway Health

Boston, MA

Carmella Jones, RN, MDiv, FCN

Director

Faith Community Nurse Program

Holy Cross Hospital

Silver Spring, MD

Raya E. Kheirbek, MD, FACP

Deputy Chief of Staff

Veterans Administration Hospital

Washington, DC

Paula Lantz, PhD

Professor and Chair

Department of Health Policy

School of Public Health and Health Services

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

David A. Lichter, DMin

Executive Director

National Association of Catholic Chaplains

Milwaukee, WI

Lucy Lowenthal

Project Manager

School of Public Health and Health Services

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

David Mayer, MD

Vice President

Quality and Safety

MedStar Health

Columbia, MD

Katherine S. McOwen, MS Ed

Director of Educational Affairs

Association of American Medical Colleges

Washington, DC

Susan Mims, MD, MPH

Vice President

Women's & Children's Medical Director

Mission Children's Hospital

Asheville, NC

Shirley Otis-Green, MSW, LCSW, ACSW, OSW-C

Senior Research Specialist

Division of Nursing Research and Education

City of Hope National Medical Center

Duarte, CA

Hiep Pham, MD, MPH

Medical Director

Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine

School of Medicine

University of South Carolina

Greenville, SC

Mandi Pratt-Chapman, MA

Director

The George Washington University Cancer Institute

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Alexander S. Preker

Lead Economist and Editor of HNP Publication Series

The World Bank

Washington, DC

Maryjo Prince-Paul, PhD, APRN, ACHPN, FPCN

Assistant Professor

Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing

Case Western Reserve University and Hospice of the Western Reserve

Cleveland, OH

Christina Puchalski, MD, FACP

Director

George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health

Professor

Department of Medicine and Health Sciences

George Washington University School of Medicine

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Nancy Reller

President

Sojourn Communications

Arlington, VA

Michael Rodgers

Senior Vice President

Catholic Health Association of the United States

Washington, DC

Congressman Tim Ryan, JD

Congressman

Author, A Mindful Nation

U.S. House of Representatives

Niles, OH

Dawn M. Schocken, MPH, CHSE-A

Director

Center for Advanced Clinical Learning

University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine

University of South Florida

Tampa, FL

Daniel Smith

Founder and President

AdvocacySmiths

Washington, DC

Anne Sokolov

Legislative Assistant

Congressman Tim Ryan

U.S. House of Representatives

Washington, DC

Lee Taft, JD, MDiv

Founder

Taft Solutions

Dallas, TX

Stephen B. Thomas, PhD

Professor

Health Services Administration

School of Public Health

Director

University of Maryland Center for Health Equity

University of Maryland

College Park, MD

Robert Tuttle, PhD, JD, MDiv

David R. and Sherry Kirschner Berz Research Professor of Law and Religion

The George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Armin D Weinberg, PhD

CEO, Life Beyond Cancer Foundation

Clinical Professor, Baylor College of Medicine

Adjunct Professor, Rice University

Houston, TX

Daniel Wolfson, MHSA

Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

ABIM Foundation

Philadelphia, PA

Appendix 2. Participants in the International Consensus Conference on Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: The Transformational Role of Compassion, Love and Forgiveness in Health Care

Andrew Allsop, MD

President

Palliative Care WA, Inc.

Watson, Australia

Amani Babgi, PhD, RN

Director of Nursing Saudiztion, Practice Education, and Research

King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam

Dammam, Saudi Arabia

Richard Bauer, MM, LCSW

Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers

Windoek, Namibia

Enric Benito, PhD

Coordinator

Palliative Care Regional Program

Balearic Islands, Spain

Noreen Chan, MD

Senior Consultant

Department of Haematology-Oncology

National University Cancer Institute

Singapore

Mark Cobb, PhD

Senior Chaplain and Clinical Director of Professional Services

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Sheffield, England

Mahmoud Daher, MPH, DrPH

Head of Country Office a.I. at WHO

Palestinian Territory

Head of WHO Sub-Office in Gaza Strip

Jerusalem

Elvira SN Dayrit MD

Public Health Specialist

San Juan City, Philippines

Manuel M. Dayrit MD

Dean

Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health

Pasig City, Philippines

Liliana De Lima, MHA

Executive Director

International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care President

Latin American Palliative Care Association

Houston, TX

Allen Dyer, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

The George Washington University

Washington, DC

Richard Egan, PhD

Lecturer in Health Promotion

Cancer Society Social and Behavioral Research Unit

Department of Preventive and Social Medicine

Dunedin School of Medicine

University of Otago

New Zealand

Giuliano Gargioni, MD

Executive Secretary

Stop TB Partnership, WHO

Geneva, Switzerland

Xavier Gomez-Batiste, MD, PhD

Director

WHO Collaborating Centre for Public Health Palliative Care Programs

Catalan Institute of Oncology Barcelona / Chair of Palliative Care. University of Vic.

Barcelona, Spain

Elizabeth Grant, PhD

Deputy Director

Global Health Academy

University of Edinburgh

Edinburgh, Scotland

George Handzo, MDiv, BCC

Director of Health Services Research and Quality

HealthCare Chaplaincy

New York, NY

Anne Hendry, MD

National Clinical Lead

NHS Scotland

Edinburgh, Scotland

Mary Hlalele, MD

CEO

Sabona Sonke Foundation

East London, South Africa

Carolyn Jacobs, MSW, PhD

Dean and Elizabeth Marting Treuhaft Professor

Smith College School of Social Work

Northampton, MA

Jan Jaworski, MD

Priest in Nauro-Gor and Surgeon

Kundiawa Hospital

Sinbu Province, Papua New Guinea

Ikali Karvinen, PhD

Principal Lecturer

Project Director

Diaconia University of Applied Sciences

Health Care Researcher

University of Eastern Finland

Helsinki, Finland

Ewan Kelly, MD, PhD

Program Director

Health Care Chaplaincy and Spiritual Care

Senior Lecturer

Christian Ethics and Practical Theology, University of Edinburgh

Edinburgh, Scotland

Suresh Kumar, MD

Director

Institute of Palliative Medicine

Medical College, Calicut

Kerala, India

Carlo Leget, PhD

Professor in Ethics of Care and Spiritual Counseling

University of Humanistic Studies

Professor in Ethical and Spiritual Questions in Palliative Care with Association for Highcare Hospices

Utrecht, The Netherlands

Mario Merialdi, MD

Coordinator

Reproductive Health and Research Department

Family, Women's and Children's Health

World Health Organization

Geneva, Switzerland

Anne Merriman, MD

Founder and Director of Policy and International Programs

Hospice Africa Uganda

Kampala, Uganda

Paterne Mombé

Director

The African Jesuit AIDS Network

Nairobi, Kenya

Daniela Mosoiu, MD, PhD

President

National Association of Palliative Care

Director of Education, Strategy and National Development

Hospice Casa Sperantei Foundation

Brasov, Romania

Faith Mwangi-Powell, MD

Chief of Party

University Research Co., LLC-Center for Human Services

Bethesda, MD

Amitai Oberman, MD

Director

Department of Geriatrics

Poriya Medical Center

Clinical Lecturer,

Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University,

Tmicha, The Israel Association of Palliative Care

Israel

Bruce Rumbold, PhD

Director, Palliative Care Unit

Department of Public Health

La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Lucy Selman, PhD

Cicely Saunders International Faculty Scholar

King's College London

Cicely Saunders Institute

Department of Palliative Care, Policy & Rehabilitation

London, England

Srinagesh Simha, MD

President

Indian Association of Palliative Care

Karunashraya Bangalore Hospice Trust

Bangalore, India

Shane Sinclair PhD

Assistant Professor

Cancer Care Research Professorship

Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary

Clinician Scientist—Person Centred Care

Alberta Health Services, Cancer Care, Tom Baker Cancer Centre

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Division of Palliative Medicine

Department of Oncology

Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary

Mieke Vermandere, MD

General practitioner and researcher

KU Leuven

Department of General Practice

Leuven, Belgium

Mariana Widmer, MD

Technical Officer

Reproductive Health and Research Department

Family, Women's and Children's Health

World Health Organization

Geneva, Switzerland

Julianna (Jinsun) Yong, PhD, RN

Professor

Director, Research Institute for Hospice and Palliative Care

The Catholic University of Korea, College of Nursing

Seoul, South Korea

Conference Coordinators

Christina Puchalski, MD, FACP

Director

George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health;

Professor

Department of Medicine and Health Sciences

George Washington University School of Medicine

The George Washington University

Washington, D.C.

Robert Vitillo, MSW

Head of Caritas Internationalis Delegation

to the United Nations in Geneva

Special Advisor on HIV & AIDS

Geneva, Switzerland

Stefano Nobile

International Delegate presso Caritas Internationalis

To United Nations Office

Geneva, Switzerland

Sharon Hull, MD, MPH, FAAFP, FACPM

Founding President

Metta Solutions, LLC

Division Chief

Department of Family and Community Medicine

DUMC, Duke University

Raleigh, NC

Appendix 3. Recommended Standards for Spiritual Care (Top 12)

1. Spiritual care is integral to compassionate, person-centered health care and is a standard for all health settings.

2. Spiritual care is a part of routine care and integrated into policies for intake and ongoing assessment of spiritual distress and spiritual well-being.

3. All health care providers are knowledgeable about the options for addressing patients' spiritual distress and needs, including spiritual resources and information.

4. Development of spiritual care is supported by evidence-based research.

5. Spirituality in health care is developed in partnership with faith traditions and belief groups.

6. Throughout their training, health care providers are educated on the spiritual aspects of health and how this relates to themselves, to others, and to the delivery of compassionate care.

7. Health care professionals are trained in conducting spiritual screening or spiritual history as part of routine patient assessment.

8. All health care providers are trained in compassionate presence, active listening, and cultural sensitivity, and practice these competencies as part of an interprofessional team.

9. All health care providers are trained in spiritual care commensurate with their scope of practice, with reference to a spiritual care model, and tailored to different contexts and settings.

10. Health care systems and settings provide opportunities to develop and sustain a sense of connectedness with the community they serve; healthcare providers work to create healing environments in their workplace and community.

11. Health care systems and settings support and encourage health care providers' attention to self-care, reflective practice, retreat, and attention to stress management.

12. Health care systems and settings focus on health and wellness and not just on disease.

Appendix 4. Fetzer Health Advisory Council, Call To Action

We call for a healthcare system: that provides caregivers–professional and family–and care receivers the opportunity to realize their full selves—physically, emotionally, socially and spiritually; that emphasizes health and healing; that honors the health of the community; and a system that promotes compassionate care, respects the dignity of those who give and receive care, and promotes love and forgiveness through relationship-centered care.

We are bold enough to say that we want a healthcare system that is spiritual, even awe inspiring! A healthcare system that will transform the hearts of those who give, receive, teach, and learn care—the culture of care and the language of care; a system that will be other regarding, moving toward justice by encouraging practitioners to work as a team to deliver service grounded in benevolence and altruism; a system that encourages self-compassion and self-care, which says to a practitioner, “You don't have to take it all on yourself;” a system that strives for equity, removing barriers due to finances, culture and individual status.

Acknowledgments

The project team is deeply grateful to the Archstone Foundation, Long Beach, California, for its initial support of this ongoing effort. Thanks also to the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, Jacksonville, Florida, and to the Fetzer Institute, Kalamazoo, Michigan, for their support that made the 2012 and 2013 conferences and this project possible. We also express gratitude to Betty Ferrell, PhD, RN, for her leadership in the 2009 conference and for her ongoing guidance in this work. Finally, we appreciate the professional expertise of Kathi E. Hanna, MS, PhD, in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Puchalski CM, Larson DB: Developing curricula in spirituality and medicine. Acad Med 1998;73:970–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astrow AB, Puchalski CM, Sulmasy DP: Religion, spirituality, and health care: Social, ethical, and practical considerations. Am J Med 2001;110:283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankl VE: Man's Search for Meaning. New York: Washington Square Press, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 4.King DE, Bushwick B: Beliefs and attitudes of hospital inpatients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract 1994;39:349–352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puchalski CM, Dorff RE, Hendi IY: Spirituality, religion, and healing in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med 2004;20:689–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulmasy DP: Is medicine a spiritual practice? Acad Med 1999;74:1002–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benito E, Oliver A, Galiana L, Barreto P, Pascual A, Gomis C, Barbero J: Development and validation of a new tool for the assessment and spiritual care of palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;13:004041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermandere M, De Lepeleire J, Van Mechelen W, Warmenhoven F, Thoonsen B, Aertgeerts B: Spirituality in palliative care: A framework for the clinician .Support Care Cancer 2013;21:1061–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermandere M, De Lepeleire J, Van Mechelen W, Warmenhoven F, Thoonsen B, Aertgeerts B: Outcome measures of spiritual care in palliative home care: A qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2013;30:437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgener SC: Predicting quality of life in caregivers of Alzheimer's patients: The role of support from and involvement with the religious community. J Pastoral Care Counsel 1999;53:433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F: The McGill quality of life questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease: A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 1995;9:207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prince-Paul M: Relationships among communicative acts, social well-being, and spirituality on quality of life at the end of life. Thesis available at https://etd.ohiolink.edu/ap/10?0::N0:10:P10_EID_SUBID:51373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, Paulk ME, Lathan CS, Peteet JR, Prigerson HG: Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, Balboni TA, Wright AA, Paulk ME, Trice E, Schrag D, Peteet JR, Block SD, Prigerson HG: Religious coping and use of intensive life prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 2009;301:1140–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestri GA, Knittig S, Zoller JS, Nietert PJ: Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2003;2:1379–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgener SC: Predicting quality of life in caregivers of Alzheimer's patients: The role of support from and involvement with the religious community. J Pastoral Care Counsel 1999; 53:433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F: The McGill quality of life questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease: A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 1995;9:207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJ, Mount LF: Existential wellbeing is an important determinant of quality of life: Evidence from the McGill quality of life questionnaire. Cancer 1996;77:576–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB: Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts JA, Brown D, Elkins T, Larson DB: Factors influencing views of patients with gynecologic cancer about end-of-life decisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;176:166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsevat J, Sherman SN, McElwee JA, Mandell K, Simbartl LA, Sonnenberg FA, Fowler FJ: The will to live among HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, Gibbons JL, Cameron JR, Davis JA: Religious struggle: Prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 2004;34:179–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J: Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol 2004;9:713–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L: Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Scientific Study Rel 1998;27:710–724 [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor P: The role of spiritual care in hospice: Are we meeting patients' needs? Am J Hosp Care 1988;5:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCord G, Gilchrist VJ, Grossman SD, King BD, McCormick KE, Oprandi AM, Schrop SL, Selius BA, Smucker DO, Weldy DL, Amorn M, Carter MA, Deak AJ, Hefzy H, Srivastava M: Discussing spirituality with patients: A rational and ethical approach. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:356–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pichora D, Shortt S, Tranmer J, Lazar N, Kutsogiannis J, Lam M; Canadian Researchers End-of-Life Network (CARENET): What matters most in end-of-life care: Perceptions of seriously patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006;174:627–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulmasy DP: A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002;42:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 2nd ed. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2009. Available at http://www.nationalcancersusproject.org [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puchalski CM, Ferrell B, Virani R, Otis-Green S, Baird P, Bull J, Chochinov H, Handzo G, Nelson-Becker H, Prince-Paul M, Pugliese K, Sulmasy D: Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009:12:885–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care. Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/projects/n-r/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care.aspx

- 32.Otis-Green S, Ferrell B, Borneman T, Puchalski C, Uman G, Garcia A: Integrating spiritual care within palliative care: An overview of nine demonstration projects. J Palliat Care 2011;15:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puchalski C, Lunsford B: The Relationship of Spirituality and Compassion in Health Care. Fetzer Institute, Kalamazoo, MI, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puchalski C: The spiritual care of patients and families at the end of life. In: Safe Passage: A Global Spiritual Sourcebook for Care at the End of Life. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan R, MacLeod R, Jaye C, McGee R, Baxter J, Herbison P: What is spirituality? Evidence from a New Zealand hospice study. Mortality 2011;16:307–324 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolan S, Saltmarsh P, Leget C: Spiritual care in palliative care: Working towards an EAPC Task Force. Eur J Palliat Care 2011;18:86–89 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selman L, Harding R, Gysels M, Speck P, Higginson IJ: The measurement of spirituality in palliative care and the content of tools validated cross-culturally: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:728–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selman L, Speck P, Gysels M, Agupio G, Dinat N, Downing J, Gwyther L, Mashao T, Mmoledi K, Moll T, Sebuyira Mpanga L, Ikin B, Higginson JI, Harding R: ‘Peace’ and ‘life worthwhile’ as measures of spiritual well-being in African palliative care: A mixed-methods study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selman L, Young T, Vermandere M, Stirling I, Leget C; Research Subgroup of the European Association for Palliative Care Spiritual Care Taskforce: Research priorities in spiritual care: An international survey of palliative care researchers and clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014. [E-pub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turoff M: The design of a policy Delphi. Technol Forecast Soc Change 1970;2:149–171 [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO: Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, June19–22, 1946; entered into force April 7, 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fetzer Institute: Health Professions Advisory Council Call Statement: Becoming Aware. Assisi, Italy: Fetzer Institute, 2012, p. 16 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senge PM: The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Random House, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Available at http://www.lcme.org/publications.htm#standards-section

- 45.Spiritual and Religious Care Competencies for Palliative Care Specialists. http://www.mariecurie.org.uk/Documents/HEALTHCARE-PROFESSIONALS/spiritual-religious-care-competencies.pdf

- 46.WHO: Review of the Constitution of the World Health Organization: Report of the Executive Board Special Group; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A: Spirituality and health: The development of a field. Acad Med 2014;89:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]