Abstract

Background

Infections with multiresistant Gram negative pathogens are rising around the world, but many European countries have recently seen a decline in infections due to methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). We determined the percentage of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus infections in Germany that were accounted for by MRSA in the past six years and looked for regional differences in the overall downward trend.

Methods

Data from the German Hospital Infection Surveillance System (Krankenhaus-Infektions-Surveillance-System, KISS) from the years 2007–2012 were analyzed. In intensive care units, data on the following nosocomial infections were registered: primary sepsis, lower respiratory tract infections, and urinary tract infections; in surgical wards, data on postoperative wound infections were collected.

Results

The number of participating intensive care units varied from 465 to 645, while the number of participating surgical wards varied from 432 to 681. Over the period 2007–2012, the percentage of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus infections that were due to MRSA dropped significantly, from 33% to 27%. More specifically, the percentage of infections due to MRSA dropped from 36% to 31% for primary sepsis and from 36% to 30% for lower respiratory tract infections. Regression analysis revealed significantly lower MRSA fractions in the German states of Brandenburg (odds ratio [OR] 0.41), Bavaria (OR 0.73), and Saxony-Anhalt (OR 0.53), with higher fractions in Berlin (OR 1.59), Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (OR 1.91), Lower Saxony (OR 1.85), and North Rhine-Westphalia (OR 1.55). There were no significant differences in the remaining German states.

Conclusion

In Germany, the percentage of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus infections due to MRSA dropped significantly over the period 2007–2012. The causes of this decline are unclear; it may have resulted from human intervention, pathogen biology, or both.

Cases of infection with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have decreased worldwide in recent years (1– 3). Recent data from the US showed a reduction of 31% in invasive MRSA infections over a period of seven years (2005–2011) (1). In the United Kingdom, where MRSA bacteremia has been a notifiable disease for a long time, the drop in rates has been even more dramatic, at 69%. The number of cases of MRSA bacteremia fell from 2935 in 2008/2009 to 924 in 2011/2012 (2). In French hospitals in the Paris region, the rate of MRSA infections dropped by 35% between 1993 and 2007—this reflects the proportion of MRSA among all strains of S. aureus (from 41% to 26.6%) as well as the incidence of MRSA (from 0.86/1000 patient days to 0.56/1000 patient days (3). In most countries in the European Union, the proportion of MRSA among invasive S. aureus infections is stagnating, or even falling significantly.

It is a well known fact that within Europe, resistance rates in MRSA are subject to wide variation, with high rates in the south and comparatively low rates in the Netherlands and Scandinavia (4). Such regional differences exist not only between individual countries but also within countries. In the US, for example, the prevalence of MRSA within individual states ranges from 0/1000 patients in South Dakota to 110.8/1000 patients in Texas, and it generally seems lower in the northwest than in the southeast (5). In Switzerland the boundary coincides with the so called “rösti ditch,” the language border between the German speaking and Francophone parts of Switzerland. In Francophone Switzerland, the proportion of MRSA among all laboratory isolated strains of S. aureus was 17.5% in 2012, whereas in the German speaking east of the country it was only 4.7% (6).

MRSA strains are still common multiresistant pathogens, even though multiresistant Gram negative pathogens are on the increase (7– 11). This study aimed to investigate in a large network of hospitals whether Germany is also subject to wide regional differences in MRSA and whether the proportion of MRSA among nosocomial infections has changed in Germany over the past six years.

Method

The Hospital Infection Surveillance System (KISS) has been in existence since 1997 and includes data on selected nosocomial infections in different risk areas, such as intensive care units or surgical wards. Participation in the scheme is voluntary, and individual participants’ data are strictly confidential. The fact that participation is voluntary explains the fact that over the years, the numbers of intensive care wards and surgical wards have varied (12, 13). The data collection was done on the basis of a uniform protocol, which also included commitments and definitions from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Surveillance of nosocomial infections and their pathogens in intensive care wards (ITS-KISS)

Information on the de novo development of a nosocomial infection of the lower respiratory tract, primary sepsis, or urinary tract infection is collected for all intensive care patients. The diagnosis is made on the basis of set definitions, which—depending on the type of infection—include combinations of microbiological and/or radiological findings in combination with clinical signs of infection (14). For each case of nosocomial infection, further variables are documented, such as confirmed pathogens, date of infection, and temporal association of the infection with devices (tracheal tube, central venous catheter, urinary catheter).

Surveillance of postoperative wound infections and their pathogens (OP-KISS)

Data on wound infections after commonly performed or particularly relevant surgical procedures—so called indicator operations—are collected from participating surgical wards. The data of operated patients are followed up postoperatively until discharge, in the entire hospital.

The following data are documented for each patient: sex, year of birth, date of surgery, type of surgery, duration of the procedure, ASA score (American Society of Anesthesiologists), wound contamination class, date of infection, type of wound infection (superficial, deep, in organ or body cavity), and pathogen.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to analyze the data for a time trend on the one hand and for geographical differences on the other hand.

The time analysis covered the years 2007 to 2012; additionally, adjustments were made for the following factors: sex and age of patients (<51, 51–65, 66–70, >70), time of year, type of hospital (university medical center, academic teaching hospital, other hospital), type of intensive care ward (interdisciplinary, internal medical, surgical, and other), as well as size of hospital (<400 beds, ≥ 400 beds). The trend was rising from 1997 to 2006, which is the reason why we restricted ourselves to evaluating the past six years only.

In order to test for significant differences between federal states we used the combined data from 2011 and 2012 and adjusted according to the structural parameters listed above. Parameters were entered into the regression model at a significance level of p≤0.05 and were removed at p>0.10.

We analyzed all data by using Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria) R 3.01 and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Out of Germany’s 2045 hospitals (status 2011), between 465 and 645 intensive care wards participated in ITS-KISS and between 432 and 681 surgical wards in OP-KISS from 2007 to 2012 (12). The respective numbers of nosocomial infections in which S. aureus or MRSA was isolated as the pathogen are listed in Table 1. For the complete time period (2007–2012) the proportion of MRSA infections among nosocomial S. aureus infections was 29.9%.

Table 1. Numbers of intensive care wards and surgical wards that collect data on nosocomial infections in the Hospital Infection Surveillance System (KISS); the proportions (%) of MRSA infections among nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus infections are given in parentheses.

| 2007/2008 | 2009/2010 | 2011/2012 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of intensive care wards | 465 | 533 | 645 | |

| Number of surgical wards | 432 | 558 | 681 | |

| Number of nosocomial S. aureus infections (incl. MRSA) | 2654 | 2727 | 2856 | 8237 |

| Number of nosocomial MRSA infections | 870 (32.8) |

836 (30.7) |

753 (26.4) |

2459 (29.9) |

| Number of nosocomial S. aureus infections (incl. MRSA) in intensive care wards | 1913 | 1965 | 2072 | 5950 |

| Number of nosocomial MRSA infections in intensive care wards | 719 (37.6) |

679 (34.6) |

627 (30.3) |

2025 (34.0) |

| Number of nosocomial S. aureus infections (incl. MRSA) in surgical wards | 741 | 762 | 784 | 2287 |

| Number of nosocomial MRSA infections in surgical wards | 151 (20.4) |

157 (20.6) |

126 (16.1) |

434 (19.0) |

MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

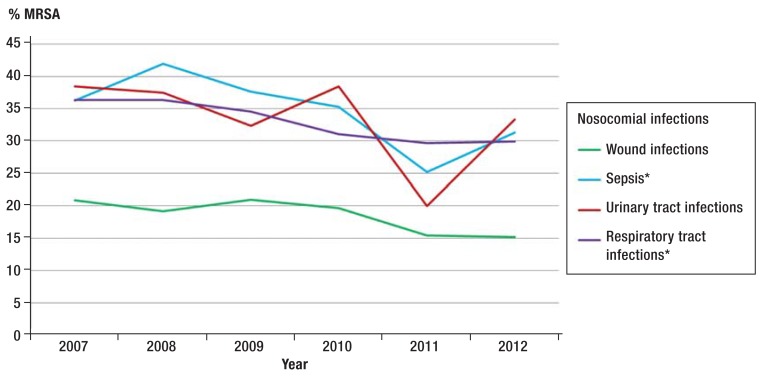

The proportion of MRSA among all nosocomial S. aureus infections (postoperative wound infections as well as primary sepsis, urinary tract infection, and lower respiratory tract infection) fell significantly (p<0.0001) over time, from 33% in 2007 to 27% in 2012. The decrease over a timer period of six years was significant in the trend analysis even when individual nosocomial infections were studied separately. Primary sepsis decreased from 36% to 31%, and infections of the lower respiratory tract decreased from 36% to 30% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Temporal development of the proportion (%) of MRSA infections among nosocomial S. aureus infections. Data from ITS-KISS and OP-KISS

*Significant trend

MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

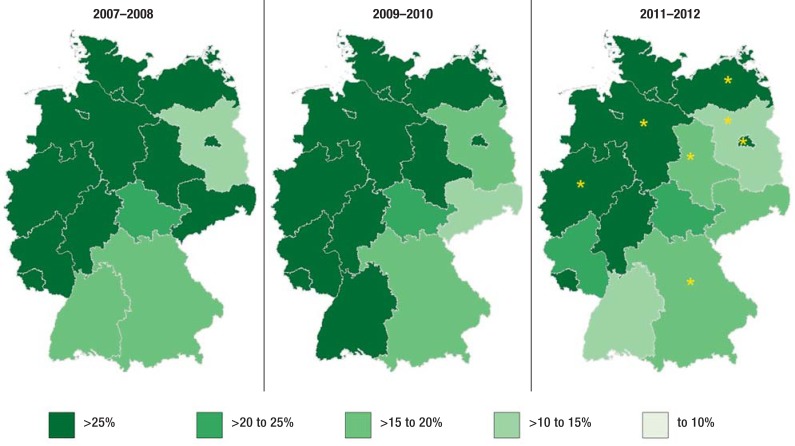

Figure 2 shows the drop in the proportion of MRSA in nosocomial S. aureus infections over time and the regional differences by federal state. Further to the decrease in the rate of MRSA over recent years, a divide between the north western and south eastern regions becomes obvious when individual regions are examined. In the regression analysis this difference reached significance for seven federal states. In the years 2011/2012 the proportion of MRSA among nosocomial S. aureus infections was significantly lower in Brandenburg (odds ratio [OR] 0.41), Bavaria (OR 0.73), and Saxony-Anhalt (OR 0.53) than in all other federal states. Significantly higher proportions of MRSA among S. aureus infections were seen in Berlin (OR 1.59), Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (OR 1.91), Lower Saxony (OR 1.85), and North Rhine–Westphalia (OR 1.55). The remaining states (Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, Bremen, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland, Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, Thuringia, Saxony) did not differ significantly from all other states. Among the tested variables, an age <51 years (OR 0.56) was identified as an independent influencing factor.

Figure 2.

Proportion (%) of MRSA among nosocomial S. aureus infections by federal state for three periods of two years (time period 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012)

*federal state is a significant influencing factor

MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Discussion

The data from the more than 600 intensive care wards and surgical wards that participate in KISS show that in Germany in 2007 to 2012, the proportion of MRSA among nosocomial S. aureus infections fell significantly, from 33% to 27%. Rates of MRSA were higher in the northern and western federal states than in those in the south and east.

Figure 1 showed that the rates of MRSA in intensive care wards were notably higher than in surgical patients: mean rates of nosocomial infections in intensive care wards (sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection) were 10% higher than those in postoperative wound infections. Most of the patients thus afflicted are cared for in normal wards. One reason for this may be that the selection pressure owing to antibiotics is usually higher in intensive care wards than in normal wards. Another reason may be different, patient-related risk factors, such as very old age and comorbidities.

Other surveillance systems in Germany also found a decrease in resistance rates of MRSA: in the Robert Koch Institute’s antimicrobial resistance surveillance (ARS) program, 23.7% of clinical isolates from inpatient departments were found to be MRSA in 2008; in 2012, this had dropped to 20.6% (15). Data collected by the Paul Ehrlich Society showed a decrease from 20.3% in 2007 to 16.3% in 2010 for all isolates from outpatient and inpatient settings (16).

Up to this point in time, Germany had to deal with increasing volumes of patients with MRSA infection and colonization, in the same way as many other countries worldwide. MRSA advanced to becoming the classic hospital pathogen, not only among experts. In order to tackle this rise, a national strategy was introduced—similarly to many other countries. In Germany, the health political focus since 2004 has been on establishing MRSA networks. This was done with the idea that successful MRSA management is possible only through regionally coordinated activities within a setting of established referral structures. Later this was followed by the national hand hygiene campaign (Aktion saubere Hände [clean hands action campaign] and in mid-2011 the obligatory laboratory notification of invasive MRSA infections. Furthermore, patients were increasingly screened on admission to hospital: the median number of nasal swabs in 2004 was 1.4/100 patients and increased to 16.7/100 patients in 2012 (17).

The answer to the question of what is responsible for the decrease in MRSA may be—in addition to the mentioned interventions—a lower selection pressure from antibiotics or the spread of fewer transmissible or virulent strains. But there are hardly any indications that this might be the case. The use of antibiotics in human medicine has not reduced in Germany in recent years, neither in the outpatient nor in the inpatient setting. There is no reason either to assume that this would have been the case in veterinary medicine (18, 19). In the meantime, MRSA is mostly detected as early as a patient is admitted to hospital: data from MRSA-KISS show that in hospitals that do a lot of screening (>15 nasal swabs per 100 patients) have shown that in 2012, more than 88% of MRSA cases were imported into the hospital, and only 11.8% could be classified as nosocomial. For the “imported” MRSA it was found, however, that such strains had mostly been acquired by past contacts with medical institutions and procedures (hospital associated MRSA) (17). In contrast to the US, so called community acquired MRSA, which as a rule affect younger patients without risk factors and without prior contact with healthcare institutions, hardly play any part in Germany (20).

A drop in rates of MRSA—starting in about 2005—in invasive infections as well as in terms of MRSA as a proportion of S. aureus isolates has been reported from many other countries, although many countries followed different strategies (Table 2) (5, 21).

Table 2. Proportion of MRSA among invasive Staphylococcus aureus isolates (in %) in Europe 2011 and trend over the time period 2008–2011; data from the European surveillance system EARS-Net (21).

| Country | % MRSA 2011 | Significant temporal trend 2008 to 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 17.4 | ▼ |

| Denmark | 1.2 | |

| Germany | 16.1 | ▼ |

| France | 20.1 | ▼ |

| United Kingdom | 13.5 | ▼ |

| Ireland | 23.7 | ▼ |

| Italy | 38.2 | |

| Netherlands | 1.4 | |

| Norway | 0.3 | |

| Austria | 7.4 | |

| Portugal | 54.6 | |

| Spain | 22.5 | ▼ |

| Sweden | 0.8 | |

| Czech Republic | 14.5 | |

| Hungary | 26.2 | ▲ |

Countries with >1000 isolates in 2011

▲ significant increase 2011 to 2008, ▼ significant decrease 2011 to 2008

MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Edgeworth asked the question of why transmissions and MRSA bacteremias in the UK halved within only two years (2006 to 2008), whereas the MRSA burden in France fell to the same extent, but slowly over many years—in spite of comparable interventions. These intervention measures included improved hand hygiene, contact isolation, and admission screening (22).

In general, it can be said that in the UK the MRSA strategy since 2005 has been rigidly oriented towards one end point (MRSA bacteremia). Furthermore, lowering the rate of MRSA bacteremia was formulated as a health political, national target, and individual hospitals will be measured and named in this context, and related data will be published. This also had consequences for individuals in positions of responsibility in some cases (23).

In France, the strategy for preventing nosocomial infections and multiresistant pathogens is oriented primarily towards collecting data on and monitoring process indicators (24). Altogether it is worth pointing out again that different countries saw a decrease, independently of their strategies.

An additional question is why there are significant differences in MRSA resistance rates in individual German states.

Factors that may constitute possible causes include:

Different degrees of compliance with hygiene measures

Different prevalence rates at hospital admission

Different use of antibiotics in the outpatient and inpatient settings

An increased occurrence of particular MRSA strains, such as livestock associated MRSA (LA-MRSA), which has been observed especially in the context of industrial animal farming

Regions with a high population density or higher density of hospital beds (25).

In terms of the prevalence of MRSA in inpatient admissions, there do actually seem to be regional differences—but the reasons for this are not clear. In 2010, 13 855 patients were screened in south Brandenburg, and only 0.8% were positive for MRSA (26); by contrast, in 2010, 20 027 patients were screened in all acute departments in Saarland in 2010, and the prevalence was almost three times as high, at 2.2% (27). Notable differences between east and west also transpired regarding the outpatient use of antibiotics: in 2007, 17 daily doses of antibiotics per 1000 members in statutory sickness funds were prescribed in Saarland, whereas in Saxony, only 9.7 daily doses were prescribed (28). Such regional data were unfortunately not available for the inpatient setting.

Some limitations apply in interpreting the KISS data. Proportions of MRSA (so called resistance rates) do not allow any conclusions regarding the number of patients with nosocomial MRSA infections, but they merely express the ratio of resistant to susceptible S. aureus infections. The advantage of resistance rates, on the other hand, is that they are not dependent on the frequency of microbiological examinations. The confirmation of a nosocomial MRSA infection according to the KISS definition is not affected by admission screening. This does not, however, apply to all MRSA infections, as community-acquired MRSA infections are not captured. Furthermore it needs to be borne in mind that the proportion of hospitals that participate in KISS is not evenly distributed in all German states or may be assumed to be representative for the states. This means that biases are conceivable.

The data from the large network of KISS hospitals show a significant decrease in the proportion of MRSA in nosocomial infections with S. aureus over the past six years. Ultimately it is not clear to what extent this decrease can be explained by interventions within and outwith hospitals (improved prevention of infection).

Key Messages.

MRSA infections have decreased in many countries in recent years.

In Germany the proportion of MRSA among nosocomial infections with S. aureus fell significantly from 2006 to 2012.

In Germany in 2012, the proportion of MRSA among nosocomial infections with S. aureus was 27% in intensive care patients and patients who had had surgery.

There seem to be differences between individual states (rates are higher in the north and west than in the south and east).

The reasons for the worldwide decrease in MRSA infections and for the differences between German states are not clear.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. 2013. Last accessed on 24 February 2014.

- 2.Public Health England. Mandatory Surveillance of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&Page&HPAwebAutoListName/Page/1191942169773. 2013. Last accessed on 24 February 2014.

- 3.Jarlier V, Trystram D, Brun-Buisson C, et al. Curbing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 38 French hospitals through a 15-year institutional control program. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170 doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson AP. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the European landscape. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarvis WR, Jarvis AA, Chinn RY. National prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in inpatients at United States health care facilities, 2010. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweizerisches Zentrum für Antibiotikaresistenzen. Resistenzdaten Humanmedizin. http://www.anresis.ch/de/index.html. Last accessed on 24 February 2014.

- 7.Mattner F, Bange FC, Meyer E, Seifert H, Wichelhaus TA, Chaberny IF. Preventing the spread of multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens: Recommendations of an expert panel of the german society for hygiene and microbiology. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(3):39–45. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott E, Saathoff S, Graf K, Schwab F, Chaberny IF. The prevalence of nosocomial and community acquired infections in a university hospital—an observational study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(31-32):533–540. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köck R, Mellmann A, Schaumburg F, Friedrich AW, Kipp F, Becker K. The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(45):761–767. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer E, Gastmeier P, Schwab F. The burden of multiresistant bacteria in German intensive care units. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1474–1476. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer E, Schwab F, Schroeren-Boersch B, Gastmeier P. Dramatic increase of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant E. coli in German intensive care units: secular trends in antibiotic drug use and bacterial resistance, 2001 to 2008. Crit Care. 2010;14:14–R113. doi: 10.1186/cc9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistik-Portal. Anzahl der Krankenhäuser in Deutschland in den Jahren 2000 bis 2012. http://de.statista.com. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 13.Zuschneid I, Rücker G, Schoop R, et al. Representativeness of the surveillance data in the intensive care unit component of the German nosocomial infections surveillance system. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:934–938. doi: 10.1086/655462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geffers C, Gastmeier P. Nosocomial infections and multidrug-resistant organisms in Germany: epidemiological data from KISS (the Hospital Infection Surveillance System) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(6) doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert Koch-Institut. Antibiotika Resistenz Surveillance. https://ars.rki.de/CommonReports/Resistenzentwicklung.aspx. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 16.Paul Ehrlich Gesellschaft. Resistenzdaten. http://www.p-e-g.org/econtext/resistenzdaten. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 17.Nationales Referenzzentrum für Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. MRSA-KISS. http://www.nrz-hygiene.de/surveillance/kiss/mrsa-kiss. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 18.Meyer E, Gastmeier P, Deja M, Schwab F. Antibiotic consumption and resistance: data from Europe and Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.GERMAP. Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human- und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. http://www.p-e-g.org/econtext/germap. 2010. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 20.Robert Koch-Institut. Eigenschaften, Häufigkeit und Verbreitung von MRSA in Deutschland - Update 2011/2012. Epidemiologisches Bulletin. 2013;21 [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2011. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/publications/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2011.pdf. 2012. Last accessed on 24. February 2014.

- 22.Edgeworth JD. Has decolonization played a central role in the decline in UK methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission? A focus on evidence from intensive care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AP, Davies J, Guy R, et al. Mandatory surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia in England: the first 10 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlet J, Astagneau P, Brun-Buisson C, et al. French national program for prevention of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance, 1992-2008: positive trends, but perseverance needed. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30 doi: 10.1086/598682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donker T, Wallinga J, Slack R, Grundmann H. Hospital networks and the dispersal of hospital-acquired pathogens by patient transfer. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pohle M, Bär W, Bühling A, et al. Untersuchung der MRSA-Prävalenz in der Bevölkerung im Bereich des lokalen MRE-Netzwerkes Südbrandenburg. Epidemiologisches Bulletin. 2012;8 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann M, Petit C, Dawson A, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Saarland, Germany: A statewide admission prevalence screening study. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GERMAP. Bericht über den Antibiotikaverbrauch und die Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen in der Human- und Veterinärmedizin in Deutschland. www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/08_PresseInfothek/Germap_2008.pdf. 2008. Last accessed on 24 February 2014.