Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) regulate cell cycle progression. Certain CDKs (e.g., CDK7, CDK9) also control cellular transcription. Consequently, CDKs represent attractive targets for anti-cancer drug development, as their aberrant expression is common in diverse malignancies, and CDK inhibition can trigger apoptosis. CDK inhibition may be particularly successful in hematologic malignancies, which are more sensitive to inhibition of cell cycling and apoptosis induction.

AREAS COVERED

A number of CDK inhibitors, ranging from pan-CDK inhibitors such as flavopiridol (alvocidib) to highly selective inhibitors of specific CDKs (e.g., CDK4/6), such as PD0332991, that are currently in various phases of development, are profiled in this review. Flavopiridol induces cell cycle arrest, and globally represses transcription via CDK9 inhibition. The latter may represent its major mechanism of action via down-regulation of multiple short-lived proteins. In early phase trials, flavopiridol has shown encouraging efficacy across a wide spectrum of hematologic malignancies. Early results with dinaciclib and PD0332991 also appear promising.

EXPERT OPINION

In general, the anti-tumor efficacy of CDK inhibitor monotherapy is modest, and rational combinations are being explored, including those involving other targeted agents. While selective CDK4/6 inhibition might be effective against certain malignancies, broad spectrum CDK inhibition will likely be required for most cancers.

1. Introduction

Cell cycle dysregulation is almost universal in cancer (1, 2), and cell cycle-mediated resistance to chemotherapy a well-established phenomenon (3). Consequently, the concept of developing agents capable of inhibiting the traverse of neoplastic cells across the cell cycle has inherent appeal. The cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are serine-threonine kinases that tightly regulate progression through the G1, S (deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis), G2 and M (mitosis) phases of the cell cycle. Many pharmacologic inhibitors of CDKs belonging to different chemical classes have been developed over the years, and some of these have been tested in clinical trials. In general, small-molecule CDK inhibitors (CDKIs) have shown most promise against hematologic malignancies. However, it appears that their therapeutic role ultimately may lie in combinatorial approaches. In this review, the major clinically relevant CDKIs are discussed from a hematologic malignancy perspective. Additionally, novel mechanisms of action of these drugs that have emerged recently are summarized, and future directions for this drug class provided.

2. The cell cycle and its regulation

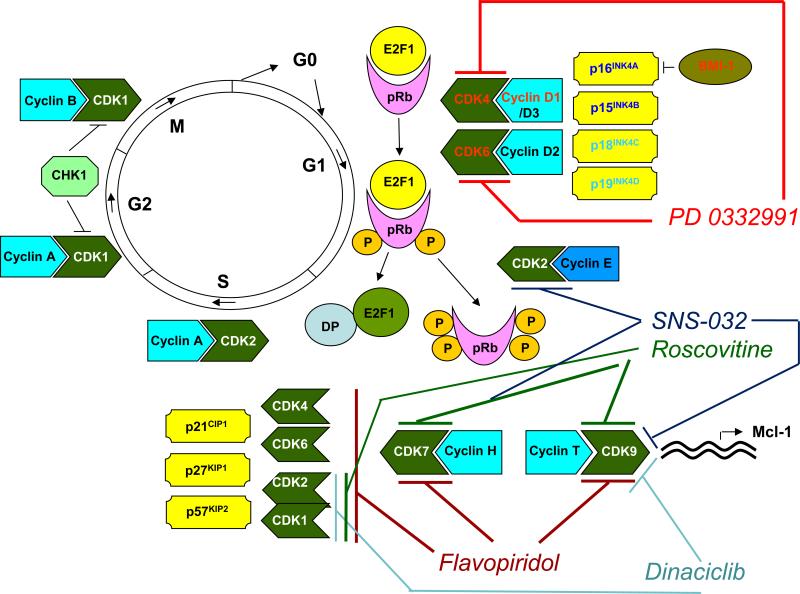

The cell cycle, the mechanism by which cells reproduce, governs the transition from quiescence (G0) to cell proliferation, and through its checkpoints, ensures the fidelity of the genetic transcript (4). It is driven by the precisely coordinated assembly, sequential activation and degradation of heterodimeric protein complexes (holoenzymes) consisting of catalytic CDKs and their regulatory partners, cyclins (5). CDKs are regulated positively by cyclins and negatively by two families of naturally occurring CDK kinase inhibitors (CKIs), the INK4 (p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b, p18Ink4c, p19Ink4d) and Cip/Kip (p21waf1, p27kip1, p57kip2) families, that inhibit the cyclin D-dependent CDKs (CDK2, -4 and -6), and CDK2/cyclin E or A, respectively (4). Cyclin binding induces a conformational change in CDKs, upon which they can be fully activated by phosphorylation at a conserved threonine residue by CDK7/cyclin H (CAK, CDK-activating kinase). When necessary, the activating phosphorylation can be reversed by the CDK-associated protein phosphatase (KAP), leading to the inactivation of CDKs (5).

Upon receipt of mitogenic signals, cells express D-type cyclins, which associate with CDKs 4 and 6. In early and late G1, respectively, the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product (Rb) is sequentially phosphorylated by CDK4/6-cyclin D and CDK2/cyclin E, leading to its inactivation. Rb-mediated inhibition of the E2F group of transcription factors is thus relieved, and the latter are fully activated, triggering the G1/S transition. Rb can be dephosphorylated by the PP1 phosphatase, which restores its growth-suppressing function after mitosis. During the S- and G2-phases, the E2F proteins are deactivated by CDK2/cyclin A, CDK1/cyclin A and CDK7/cyclin H complexes, thereby turning off E2F-dependent transcription. The timely inactivation of E2F is critical for orderly S- and G2-phase progression. Levels of cyclins A and B rise in late S-phase and throughout G2. Cyclins that are no longer needed are targeted for proteasomal degradation by phosphorylation at specific residues. Mitotic entry (G2/M transition) is controlled by CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B, the activity of which is tightly regulated by its phosphorylation status at specific threonine residues, both an activating phosphorylation catalyzed by CAK and inhibitory phosphorylations catalyzed by Wee1 and Myt1. For mitosis to occur, CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B must be activated by a phosphatase, CDC25C. At the completion of the S-phase, Wee1 is degraded by proteolysis and CDC25C activated by a regulatory phosphorylation, leading to CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B activation and commencement of mitosis. Upon DNA damage, however, the checkpoint kinases ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM and Rad3-related (ATR), acting via Chk1 and Chk2, phosphorylate (and thereby inhibit) CDC25C, halting further S-phase and G2 progression and mitotic entry. Similarly, at the G1/S and intra-S-phase checkpoints, these kinases phosphorylate (and thereby inhibit) the CDC25A phosphatase in response to DNA damage, thus preventing CDK2/cyclin E activation and temporarily halting the cell cycle. The checkpoint kinases also stabilize the tumor suppressor gene product p53, an important sensor of DNA damage and monitor of genomic integrity often referred to as “the guardian of the genome”. p53, via transcriptional activation of the Cip/Kip family CKI p21waf1, inhibits CDK2/cyclin E and preserves the association of Rb with E2F. These concepts have been reviewed (2, 4-6) and are depicted schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proteins implicated in the regulation of human cell cycle progression, and potential mechanisms by which current, clinically relevant CDK inhibitors disrupt cell cycle regulation. See text for details.

In addition to its known role at the G2/M boundary, CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B is also involved in mitotic progression and the mitotic, or spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC). In the presence of unaligned chromosomes, separase is kept inactive by securin and CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B. Under these conditions, sister chromatids are held together by cohesins. Upon complete bipolar attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle, CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B and securin are ubiquitylated by anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C)-cell division control 20 (CDC20) in a SAC-dependent manner, leading to the activation of separase, which in turn cleaves cohesins and releases sister chromatids, facilitating the metaphase-anaphase transition (1). Centrosome maturation is critical for cell division and begins with centriole duplication, which occurs in G1 and is triggered by CDK2/cyclin E and CDK2/cyclin D activity (4). Finally, the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein survivin is stabilized through phosphorylation during mitosis by CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B and plays an important role in the regulation of the mitotic spindle and the preservation of cell viability (2, 4).

3. Transcriptional CDKs

Apart from serving as the engines of the cell cycle, several CDKs play important roles in cellular transcription. These include CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B, CDK7/cyclin H, CDK8/cyclin C, CDK9/cyclins T and K and CDK11/cyclin L (7). The major transcriptional CDKs are CDK7/cyclin H and CDK9/cyclin T, which phosphorylate the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the largest subunit of ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase II (RNA pol II) at specific serine residues (5). CTD phosphorylation of RNA polII is not only essential for transcription, but also serves as a platform for RNA processing and chromatin regulation (8). Transformed cells rely on continuous activity of RNA polymerase II to resist oncogene-induced apoptosis (9). CDK7/cyclin H/MAT1 facilitates transcriptional initiation as a component of the transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) complex, while CDK9/cyclin T (phospho-transcription elongation factor b, p-TEFb) promotes transcriptional elongation (2). On the other hand, CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B and CDK8/cyclin C appear to repress transcription through inhibitory phosphorylation of the CTD of RNA polymerase II (4, 7).

4. Rationale for therapeutic targeting of CDKs

Perturbations of the cell cycle, particularly alterations of the cyclin D-CDK4/6-INK4-pRb-E2F cascade, are extremely common in neoplastic cells (4, 7). Overexpression of cyclins (e.g., cyclins D1 and E1), amplification of CDKs (e.g., CDK4/6), inactivation of critical CKIs (e.g., p16Ink4a, p15Ink4b, p21waf1, p27kip1), loss of Rb expression, and loss of binding of CKIs to CDKs (e.g, INK4 binding to cyclin D-dependent CDKs) all occur frequently in human malignancies due to chromosomal translocations, genetic mutations or by epigenetic mechanisms (1, 2, 6). CDK-cyclin complexes are, therefore, overactive in most cancers and their pharmacological inhibition thus causes cell cycle arrest (10) and induces apoptosis selectively in transformed cells (11). However, while cyclin B1 depletion inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human tumor cells (12), selective inhibition of CDK2, which appears to be dispensable for tumor cell proliferation, is unlikely to be of therapeutic benefit (13). Sustained proliferation of several different cancer cell lines despite inhibition or depletion of CDK2 by a variety of mechanisms suggests that increased levels of CDK4 or E2F activity in cancer cells may compensate for the requirement for CDK2 activity for proliferation (13).

Another aspect of therapeutic CDK inhibition particularly applicable to hematologic malignancies, which are often characterized by defects in apoptotic pathways, involves the global repression of transcription by drugs that inhibit CDK7/9 (7). Transcriptional CDKIs down-regulate a large number of short-lived anti-apoptotic proteins, such as the anti-apoptotic proteins myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1), B-cell lymphoma extra long (Bcl-xL) and XIAP (X-linked IAP), D-cyclins, c-myc, Mdm-2 (leading to p53 stabilization), p21waf1, proteins whose transcription is mediated by nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (2). In particular, diverse hematologic neoplasms, from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (14) to B-cell lymphoma (15), multiple myeloma (MM) (16-19) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (20) have been shown to be critically dependent on Mcl-1. As such, down-regulation of Mcl-1 by transcriptional inhibition might represent the major mechanism underlying CDKI efficacy in these diseases (17, 18, 20, 21), and provide a strong rationale for combination strategies (discussed in detail later in the article). Interestingly, one study reported induction of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 in leukemic blasts of patients with refractory AML receiving flavopiridol, perhaps representing a compensatory increase in Bcl-2 expression in response to the transcriptional down-regulation of its anti-apoptotic partner Mcl-1 (22). Inhibitors of p-TEFb might be particularly efficacious in CLL (23). Additionally, in MM, dysregulation of cyclin D1 sensitizes tumor cells to the actions of CDKIs through interference with p21 expression, dephosphorylation of pocket proteins and inactivation of E2F proteins culminating in S-phase entry, as well as inactivation of NF-κB, leading to apoptosis rather than growth arrest (24).

It has not been possible thus far to develop an inhibitor that is absolutely selective for a single CDK, largely because of the lack of three-dimensional structural models for many CDKs and high structural homology within the CDK family. The high frequency of cyclin D-CDK4/6-INK4 pathway aberrations in cancer has led to substantial interest in developing selective inhibitors of CDK4/6. Of note, such a strategy would be expected to succeed only in cells with intact Rb function, and indeed, this has proved to be true in the case of PD-0332991, a highly selective CDK4/6 inhibitor (discussed further in the following sections) (25). However, while this approach might be effective against CDK4/6-dependent tumors such as mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and MM (25, 26), concomitant inhibition of the transcriptional CDKs is likely to be key in most cancers. Preclinical studies have shown that combined depletion of cell cycle and transcriptional CDKs most effectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells (27). Of note, transcriptional CDKIs have been reported to effectively target quiescient CD34+CD38− cells, the putative leukemia-initiating cells in AML (28).

5. New insights into CDK functions and mechanisms of action of CDKIs

A considerable amount of evidence has accumulated in recent years implicating CDKs in the regulation of the DNA damage response (DDR) network, including a substantial role in DNA repair. While CDK1 and CDK2 activities are down-regulated at the end of the DNA damage checkpoint signaling pathway, causing cell cycle arrest and allowing DNA repair to occur, CDKs have been found to play critical roles upstream in the initiation of checkpoint control and DNA repair (29). CDK inhibition in normal and malignant cells leads to down-regulation of Chk1 and activates the DDR (30). In addition to the known importance of CDKs in the regulation of the DDR in interphase cells, it has recently been shown that during mitosis, CDK1 attenuates the interaction between mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 (MDC1), a master DDR organizer, and histone γH2AX, a marker of DNA damage, which is required to trigger robust repair (31). CDKs phosphorylate BRCA2 at a specific serine residue (S3291) to inhibit its interactions with the essential recombination protein RAD51, and this might act as a molecular switch to regulate RAD51 recombination activity (32). CDK1, the only CDK that is essential for mammalian cell cycle progression in that mouse embryos lacking all interphase CDKs (CDK2, CDK3, CDK4 and CDK6) undergo organogenesis and develop to midgestation (33), is required for DNA double strand break (DSB) end resection, homologous recombination (HR) and DNA damage checkpoint activation in yeast (34). In yeast, CDK-mediated phosphorylation of the Sae2 protein controls DNA DSB resection, an event necessary for HR but not non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), thus governing the choice between these two major mechanisms for DNA DSB repair (35). Efficient ATM-dependent ATR activation in response to DSBs is restricted to the S- and G2-phases and requires CDK activity (36). Previously thought to be redundant in the control of cell cycle progression (13), CDK2 may play a role in both HR and NHEJ pathways of DNA repair, suggesting that CDK2 inhibition might selectively enhance cancer cell responses to DNA-damaging agents, and that CDKIs could be useful against tumors harboring defects in DNA repair, such as BRCA1 mutations (37). CDK2 also phosphorylates minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins during DNA replication, thus blocking continued replication origin firing. CDK2 inhibition, therefore, causes over-replication, resulting in the formation of DSBs and single stranded DNA intermediates that activate ATM and ATR, eliciting an intra-S-phase checkpoint (38, 39). Most recently, chemical genetics experiments have revealed a non-redundant requirement for CDK2 activity in the DDR and a specific target of CDK2 (Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome gene product 1, Nbs-1) within the DNA repair machinery (40). Furthermore, as CDK1 participates in BRCA1-dependent S-phase checkpoint control (phosphorylates BRCA1) in response to DNA damage, its inhibition, by compromising the ability of cells to repair DNA by HR, could also selectively sensitize BRCA1-proficient cancer cells to DNA-damaging treatments (41) and poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (42) by disrupting BRCA1 function. Selectively targeting either CDK1 or CDK2 may thus represent an optimal approach for CDKI-DNA-damaging agent combination therapy (29). However, these concepts have primarily been tested in the context of solid tumors. It has recently been demonstrated that CDK1 phosphorylates the granulopoiesis-promoting transcription factor C/EBPα (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha) at serine 21, inhibiting its differentiation-inducing function (43). CDK1 inhibition relieved the differentiation block in fms-like tyrosine kinase (FLT3)-mutated AML cell lines as well as in primary patient-derived cells, suggesting that this approach might have therapeutic potential in FLT3-mutant AML. Indeed, data from the serial “FLAM” trials (see below) have demonstrated that FLT3-mutant AMLs are particularly susceptible to the strategy of timed sequential therapy with flavopiridol, cytarabine and mitoxantrone. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as a mechanism of cell death, and of a cytoprotective autophagic response were recently described both in CLL cell lines and patient-derived CLL cells exposed to the pan-CDKI flavopiridol (44). Finally, the CDKI R-roscovitine has been reported to prevent alloreactive T-cell clonal expansion through CDK2 inhibition and protect against acute graft versus host disease (GvHD) (45).

6. Selected small-molecule CDKIs under investigation for hematologic malignancies: preclinical and single agent studies

In the following paragraphs, selected pharmacological inhibitors of CDKs of therapeutic relevance in hematologic malignancies are discussed. Table 1 summarizes the key features of agents that have been studied in patients with hematologic malignancies. Agents such as UCN-01, whose effects may be attributed to inhibition of Chk1, protein kinase C (PKC) and 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK-1) in addition to several CDKs, and bryostatin-1, best regarded as a PKC modulator, are not considered further in this review.

Table 1.

Major clinically relevant CDK inhibitors

| Agent, manufacturer | Chemistry | CDKs targeted | Hematologic malignancies studied | Phase of clinical development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavopiridol (alvocidib, Sanofi-Aventis) | Semisynthetic flavonoid | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9 (pan-CDK inhibitor) | AML, CLL, NHL, MM, ALL, CML | II |

| R-roscovitine (seliciclib, CYC202, Cyclacel) | Trisubstituted purine | 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 9 | No clinical trials in hematologic malignancies | II (solid tumors) |

| SNS-032 (BMS-387032, Sunesis, Bristol-Myers Squibb) | Aminothiazole | 2, 7, 9 | CLL, MM, NHL | I |

| Dinaciclib (SCH 727965, Merck) | Pyrazolopyrimidine | 1, 2, 5, 9 | CLL, MM, NHL, AML, ALL, PLL | II |

| PD0332991 (Pfizer) | Pyridopyrimidine | 4, 6 | MCL, MM, AML, ALL, MDS | III (breast cancer) |

Abbreviations: CDK, cyclin dependent kinase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; PLL, prolymphocytic leukmia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome

6.1. Flavopiridol (alvocidib)

Flavopiridol (alvocidib, HMR-1275, NSC 649890, L86-8275, Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, Paris, France) is a semi-synthetic flavonoid derived from rohitukine, an alkaloid isolated from the leaves and stems of Amoora rohituka and Dysoxylum binectariferum, plants indigenous to India. It is a pan-CDKI, potently inhibiting at least CDKs 1, 2, 4/6, 7 and 9, as well as a number of other protein kinases (7). In addition to anti-proliferative effects leading to cell cycle arrest in tumor cells, the drug was shown to be particularly effective in inducing apoptosis in a variety of hematopoietic cell lines (46). Subsequent studies revealed flavopiridol to be a global inhibitor of transcription, particularly affecting cell cycle and apoptosis regulators with shortlived mRNAs (47). Indeed, the compound inhibits CDK9/cyclin T with such potency that competition with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is not detectable, thus inactivating p-TEFb and blocking most RNA transcription in vivo (48). In the human monocytic AML cell line U937, flavopiridol induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial (intrinsic) rather than the receptor-mediated (extrinsic) pathway (49).

Flavopiridol was the first CDKI to enter clinical trials in humans. Despite promising single-agent preclinical efficacy against CLL, the results of early clinical trials of flavopiridol monotherapy employing either 72-hour continuous or 1-hour bolus infusion schedules were, in general, disappointing, leading to a search for alternative schedules of administration (50). In a small phase II trial using 1-hour infusions of flavopiridol for 3 consecutive days every 21 days in patients with advanced MM, no activity was observed in vivo (51). Even ex vivo, cytotoxicity was observed only after longer exposure times at higher flavopiridol concentrations than achievable in vivo. However, a phase II trial in patients with relapsed mantle cell lymphoma utilizing an identical schedule reported modest single-agent activity (52). While administration by 24-hour continuous infusion was of no benefit in patients with relapsed, fludarabine-refractory CLL (53), a “hybrid” schedule of administration (30-minute loading dose followed by 4-hour infusion) based on pharmacokinetic modeling and designed to achieve and sustain effective concentrations of free drug in plasma was associated with marked clinical efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory, genetically high-risk CLL (54). Indeed, the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) in this phase I trial was tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). Flavopiridol area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) correlated with clinical response and cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and glucuronide metabolite AUC correlated with TLS (55). These results were confirmed in the phase II setting (56). This novel schedule of administration of flavopiridol was also tested in a phase I trial in patients with relapsed/refractory acute leukemias (57). TLS was excluded as a DLT in this study. Although flavopiridol led to marked, immediate cytoreduction in these patients, objective clinical responses were uncommon. Secretory diarrhea proved to be the DLT. Recently, hematologic improvement after flavopiridol treatment has been reported in a patient with hairy cell leukemia refractory to pentostatin and rituximab (58).

6.2. R-Roscovitine (seliciclib)

R-Roscovitine (seliciclib, CYC202, Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals, Berkeley Heights, NJ, Dundee, UK) is an orally administered, trisubstituted purine derivative of olomoucine that selectively inhibits CDKs 1, 2, 5, 7, 8 and 9 (1, 5). It is a more potent inhibitor of CDK2 than CDK1 and was the second CDKI to enter clinical trials in humans. Seliciclib potently down-regulates Mcl-1 via inhibition of transcription, triggering apoptosis in human leukemia and MM cells (17, 18, 21). In human MM cell lines, seliciclib induces apoptosis accompanied by down-regulation of Mcl-1 and p27, and eliminates adhesion-mediated drug resistance (59). Seliciclib exposure of human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells results in G1- and G2/M-phase arrest and induction of apoptosis independently of underlying chromosomal translocations (60). However, no clinical trials of this agent in hematologic malignancies have been conducted.

6.3. SNS-032 (BMS-387032)

SNS-032 (BMS-387032, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) is an acyl-2-aminothiazole compound that potently inhibits CDKs 2, 7, and 9 (and much less potently CDK1 and CDK4) as well as glycogen synthase kinase-3-beta (GSK3β) (1, 61). In CLL cells, SNS-032 induces apoptosis more potently than flavopiridol or roscovitine, via inhibition of RNA pol II and depletion of the anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1 and XIAP (20). In MCL cell lines, SNS-032 similarly down-regulates Mcl-1 and cyclin D1 via transcriptional repression, but the degree of apoptosis induced varies between cell lines, indicating that the latter have distinct mechanisms sustaining their survival (62). Appropriate target modulation by SNS-032 (i.e., inhibition of CDKs 2, 7 and 9) has also been shown in MM cell lines (63).

Based upon these observations, a phase I trial of SNS-032 was conducted in patients with advanced CLL and MM (64). SNS-032 was administered as a loading dose followed by 6-hour infusion weekly for 3 weeks of each 4-week cycle. TLS was the DLT for CLL, with 75 mg/m2 being identified as the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). No DLT was observed in the MM patients and the MTD not identified up to 75 mg/m2. However, despite demonstration of mechanism-based pharmacodynamic activity (inhibition of CDK7/9, leading to down-regulation of Mcl-1 and XIAP and induction of apoptosis in CLL cells), clinical activity was limited and the study was closed early.

Recently, SNS-032 has been shown to down-regulate via inhibition of transcription the oncogenic fusion proteins FIP1-like-1 (FIP1L1)-platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) and Bcr-Abl (breakpoint cluster region-Abelson) in tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)-resistant hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells (65). SNS-032 also decreased the phosphorylation of downstream molecules in these cells and induced apoptosis by triggering both the mitochondrial (intrinsic) and death receptor (extrinsic) pathways. SNS-032 kills primary AML cells with a potency more than 35-fold higher than that of cytarabine, with which it also exhibits striking synergism (66).

6.4. Dinaciclib (SCH 727965)

Dinaciclib (SCH 727965, Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) inhibits CDKs 1, 2, 5 and 9 and, compared with flavopiridol, exhibits superior activity with an improved therapeutic index in preclinical studies, inducing regression of established solid tumors in a range of mouse models following intermittent scheduling of doses below the MTD (67). Preclinical testing in a number of cell lines and xenograft models of common childhood malignancies suggested greatest efficacy against leukemias (68). In patient-derived CLL cells, dinaciclib promotes apoptosis and abrogates microenvironmental cytokine protection (69). Dinaciclib potently inhibited the growth of AML and ALL (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) cell lines in vitro and induced apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway, down-regulating Mcl-1 by decreasing phosphorylation of the CTD of RNA pol II through CDK9 inhibition (70). It also decreased XIAP and Bcl-xL expression, and inhibited Rb and Bad phosphorylation, all findings that were confirmed in primary leukemia cells.

Dinaciclib at a dose of 12 mg/m2 (established as the recommended phase II dose (RPTD) in a phase I trial in patients with solid tumors) administered by 2-hour infusion on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day cycle exhibited promising clinical activity in heavily pre-treated patients with low, intermediate and high grade lymphomas, primarily follicular lymphoma (FL) and DLBCL (71). CRS, manageable with steroids and not requiring treatment discontinuation, was observed in four patients. The RPTD of dinaciclib administered on this schedule to heavily pre-treated patients with CLL was found to be 14 mg/m2 (72). A rapid decrease in Mcl-1 was noted, and DLTs included bacterial pneumonia and TLS requiring temporary dialysis at the 17 mg/m2 dose. High response rates (RRs) were observed, including in patients with extensive prior treatment, bulky disease or poor-risk cytogenetics (17p deletion). Common toxicities observed in these two trials included myelosuppression, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, hyperglycemia, hypocalcemia and elevated transaminases (71, 72).

Dinaciclib was administered at a dose of 50 mg/m2 by 2-hour infusion once every 21 days in a phase II trial in adults with advanced AML (patients ≥ 60 only) or ALL (73). AML patients were randomized between dinaciclib and gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) with cross-over to dinaciclib if no response to GO was seen, while ALL patients only received dinaciclib. Intra-patient dose escalation of dinaciclib to 70 mg/m2 in cycle 2 was allowed. Although anti-leukemia activity was observed in 60% of patients, there were no objective responses. TLS was a notable toxicity, with one fatality. Mcl-1 levels declined post-treatment, but rapidly recovered. This, along with the short half-life of dinaciclib (1.5-3.3 hours), led the investigators to propose that longer infusion schedules or more frequent drug administration would be necessary (70, 73).

Based upon the finding of high CDK5 expression in MM with relatively low expression in other organs suggesting a large therapeutic window, a phase I/II trial of dinaciclib was conducted in patients with relapsed MM (74). Dinaciclib was administered on day 1 of a 21-day cycle at doses of 30–50 mg/m2. 50 mg/m2 was determined to be the MTD and was the dose used in the Phase II portion. Although the overall confirmed RR was 11%, two patients achieved a very good partial response (VGPR), and many obtainined some degree of monoclonal protein stabilization or decrease. Adverse events were similar to those reported in the CLL and lymphoma studies.

6.5. PD0332991

PD0332991 (Pfizer, Inc., New York City, NY) is an orally administered, highly specific inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6 (at slightly higher concentrations) (25). It is a potent anti-proliferative agent against Rb+ tumor cells in vitro, inducing an exclusive G1 arrest, with concomitant elimination of phospho-Rb and inhibition of E2F-dependent transcription, sufficient to cause tumor regression in human colon carcinoma xenograft models. Acting in concert with the endogenous CKI p18Ink4c, PD 0332991 potently induces G1 arrest, but not apoptosis, in primary bone marrow MM cells ex vivo and prevents tumor growth in disseminated human MM xenografts (75). However, PD 0332991 markedly enhances the killing of myeloma cells by dexamethasone. Additionally, it may impairs osteoclast progenitor pool expansion and block osteolytic lesion development in MM (76). PD0332991 profoundly suppresses, at low nanomolar concentrations, Rb phosphorylation, proliferation, and cell cycle progression at the G0/G1 phase of MCL cell lines and patient-derived MCL cells, which are characterized by constitutive activation of the cyclin D1 signaling cascade (77). It has recently been suggested that PD 0332991 may both inhibit tumor growth in CDK4/6-dependent tumors and ameliorate the dose-limiting toxicities of chemotherapy in CDK4/6-indepdendent tumors, although it should not be combined with DNA-damaging therapies to treat tumors that require CDK4/6 activity for proliferation (26). In AML cell lines bearing the FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutation, PD 0332991 caused sustained cell cycle arrest and prolonged survival in an in vivo model of FLT3-ITD AML (78). However, this was overcome by down-regulation of p27kip1 and reactivation of CDK2.

A pharmacodynamic study of PD 0332991 in 17 patients with relapsed MCL was recently reported (79). Five patients achieved progression-free survival of greater than a year, with 1 complete and 2 partial responses (PRs). These patients demonstrated large reductions in summed maximal standard uptake value (SUV(max)) on 3-deoxy-3[(18)F]fluorothymidine (FLT) positron emission tomography (PET), as well as in expression of phospho-Rb and the proliferation marker, Ki67.

6.6. Other CDKIs demonstrating preclinical activity against hematologic malignancies

The CDK-inhibitory effects of a variety of other molecules derived from a number of different chemical classes have been studied in hematologic malignancies. While some of these are currently in clinical trials, others remain at preclinical stages of development. Additional CDK and non-CDK targets of a number of the putatively selective CDKIs have been found, and others remain under active investigation. Indeed, some of these agents are multi-kinase inhibitors, targeting other kinases relevant to hematologic malignancies, such as FLT3, Bcr-Abl, Src and Janus kinases (JAK), in addition to CDKs. An overview of some of these agents is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Other CDK inhibitors in earlier stages of development

| Agent (reference) | Chemistry | CDKs targeted | Other targets/mechanisms | Hematologic malignancies studied | Phase of development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGP74514A (119) | Trisubstituted purine | 1 | MAPK and JNK activation | AML, ALL | Preclinical |

| SU9516 (120) | 3-substituted indolinone | 2 | Inhibition of phosphorylation of CTD of RNA pol II (cyclin T/CDK9) | AML, ALL | Preclinical |

| RGB 286638 (121) | Indenopyrazole | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 | RNA pol II, JAK2, Bcr-Abl, Src, FLT3, GSK3, AMPK, PIM and HIP kinases | MM | Phase I (solid tumors) |

| Purvalanol (122) | 2,6,9-trisubstituted purine derivative | 1, 2, 5 | RNA pol II, MAPK and JAK/STAT pathways, Src | MM | Preclinical |

| AT7519 (123, 124) | 2,6-dichlorophenyl derivative of indazole | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6,9 | GSK3β activation | MM, CLL, NHL, MCL | Phase II |

| NVP-LCQ195/AT93 11 (LCQ195) (125) | Achiral heterocyclic small molecule | 1, 2, 3, 5,9 | CLK3, Chk2 | MM | Preclinical |

| LDC-000067 (126) | Not available | 9 | NF-κB pathway | MM | Preclinical |

| P276-00 (127-130) | Flavone | 1, 4, 9 | MM, MCL | Phase II | |

| SB1317 (TG02) (131, 132) | Macrocyclic pyrimidine | 1, 2, 7, 9 | JAK2, FLT3 | AML, ALL, MDS, PV, MM, CLL, SLL | Phase I |

Abbreviations: CDK, cyclin dependent kinase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; PV, polycythemia vera; SLL, small lymphocytic leukmia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; FLT3, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; Chk2, checkpoint kinase 2; Bcr-Abl, breakpoint cluster region-Abelson; RNA pol II, ribonucleic acid polymerase II; MAPK, mitogen activated protein kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3-beta; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase; HIP, homeodomain-interacting protein; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; CTD, carboxyl terminal domain

7. Rational combinations involving CDKIs

Early preclinical studies revealed marked sequence-dependent cytotoxic synergism between various neoplastic agents and flavopiridol, with flavopiridol-induced G1 and G2 arrest antagonizing the effects of subsequently administered S-phase-active agents, whereas there was dramatic enhancement of apoptosis when flavopiridol was applied after cells had been arrested in mitosis (80). SAC activation due to microtubule stabilization leads to elevated activity of CDK1 (cdc2) and increased expression of survivin, which in turn is stabilized by CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B-mediated phosphorylation (81). Inhibition of CDK1 (cdc2) in this setting leads to massive apoptosis. Furthermore, exit from mitotic arrest (“adaptation”) following SAC engagement requires CDK1 (cdc2)/cyclin B; inhibition of the latter after SAC activation facilitates mitotic slippage and exit, and speeds cell death (2).

The ability of flavopiridol to trigger apoptosis in leukemic cells and recruit surviving leukemic cells to a proliferative state, thereby priming such cells for the S-phase-related cytotoxicity of cytarabine led to the design of clinical trials of “timed sequential therapy” (TST) with flavopiridol, cytarabine and mitoxantrone (FLAM) (82). In a phase I trial, the regimen yielded RRs of 31% and 12.5% among adults with relapsed/refractory AML and ALL, respectively (83). Flavopiridol was given by 1-hour bolus daily for 3 days beginning day 1, followed by 2 g/m2/72 hours cytarabine beginning day 6, and 40 mg/m2 mitoxantrone beginning day 9. In a phase II trial of this regimen using flavopiridol doses of 50 mg/m2/day in newly diagnosed adults with poor-risk AML, the complete response (CR) rate was 67% (84). A phase I trial of “hybrid FLAM” in adults with relapsed/refractory acute leukemias found the RPTD of flavopiridol administered in a “hybrid” fashion to be a 30 mg/m2 bolus followed by a 60 mg/m2 infusion daily for 3 days (85). However, a randomized phase II study comparing “bolus” with “hybrid” FLAM found comparably encouraging results in adults with poor-risk AML with both schedules of flavopiridol (86). As such, and given its greater convenience, an ongoing randomized phase II trial comparing FLAM with “7+3” in newly diagnosed younger adults with intermediate or poor-risk AML is utilizing bolus administration of flavopiridol (87). In a preliminary analysis, the investigators reported CR rates of 68% with FLAM, compared with 48% and 52% with one or two cycles of “7+3”, respectively. The combination of flavopiridol, fludarabine and rituximab (FFR) was studied in a phase I trial in patients with MCL, CLL or indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (B-NHL) (88). The overall RR was 82%, inclusive of 50% CRs and 26% PRs. 80% of patients with MCL responded.

Besides combinations of CDKIs with conventional cytotoxic agents as discussed above, there has been substantial interest in combining them with other novel and targeted agents. In this regard, the ability of pharmacologic CDKIs to convert drug-induced differentiation into apoptosis has led to combination studies with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) and PKC activators. Thus, vorinostat and flavopiridol interact synergistically to induce mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in human acute leukemia cells (89), a phenomenon that is at least partly attributable to Mcl-1 and XIAP down-regulation (90) and NFκB pathway disruption (91), and is not overcome by overexpression by Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, often responsible for resistance to conventional cytotoxic agents such as cytarabine (92). Down-regulation by flavopiridol of p21waf1/cip1, which is induced by HDACIs, has been shown to underly its synergistic induction of apoptosis with the HDACI sodium butyrate in human acute leukemia cells (93, 94). Similar findings have been reported in preclinical studies of the combination of roscovitine and the HDACI LAQ824 (95). Based upon these observations, a phase I trial of flavopiridol and vorinostat in patients with relapsed or refractory acute leukemias (NCT00278330) was conducted (Holkova B, et al. Clinical Cancer Research 2013, in press). Although no objective responses were seen, sustained plasma concentrations of flavopiridol high enough to mimic the pre-clinical in vitro findings were achieved. Synergistic induction of apoptosis in human AML cells by flavopiridol and the differentiation inducers phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or bryostatin 1 has been shown to result from both intrinsic and extrinsic pathway activation, due to mitochondrial damage and PKC-dependent induction and release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (96-98).

The combination of CDKIs with proteasome inhibitors constitutes a dual attack potentially applicable to multiple hematologic malignancies. In preclinical studies, proteasome inhibitors strikingly lower the apoptotic threshold of leukemic cells exposed to pharmacologic CDKIs, with NFκB pathway interruption and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation likely playing key roles in this phenomenon, besides down-regulation of Mcl-1, XIAP and p21cip1 (99). These findings were recapitulated in imatinib-sensitive and –resistant Bcr-Abl+ leukemia cells where, additionally, Bcr-Abl down-regulation with marked reduction in activity of downstream pathways were seen (100). A phase I trial of bortezomib and flavopiridol (administered in a “hybrid” fashion) in patients with recurrent or refractory MM, indolent B-NHL and MCL documented an overall RR of 44% (2% CRs and 31% PRs) (101). When flavopiridol was administered in a non-hybrid fashion, the regimen yielded an overall RR of 33% in this patient population (102).

In human Bcr-Abl+ leukemia cells, flavopiridol potentiates imatinib-induced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis accompanied by Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 down-regulation and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and JNK activation (103). These findings formed the basis of a phase I trial of flavopiridol and imatinib in advanced Bcr-Abl+ leukemias (104). The combination was tolerable and produces encouraging responses, including in some patients with imatinib-resistant disease.

The ability of CDK7/9 inhibitors to down-regulate several short-lived anti-apoptotic proteins, notably Mcl-1, makes their combination with BH3-mimetics, such as ABT-737 or obatoclax, particularly appealing since such an approach has the potential to simulataneously target multiple arms of the apoptotic regulatory machinery. Thus, roscovitine dramatically increases ABT-737 lethality in human leukemia cells (21). Roscovitine and ABT-737, a specific inhibitor of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, respectively untether the apoptosis effector Bak from Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, respectively, triggering Bak activation and Bax translocation, culminating in apoptosis. Flavopiridol and the pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor obatoclax synergistically triggered apoptosis in both drug-naive and drug-resistant MM cells via down-regulation and inhibition of Mcl-1 and up-regulation and release of Bim, accompanied by activation of Bax/Bak (105). Free radical-dependent oxidant injury and JNK activation were found to be additional contributors to the lethality of combined treatment of MM cells with flavopiridol and another pan-Bcl-2 inhibitor, HA14-1 (106). Combined exposure to flavopiridol and TNF receptor related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) simultaneously activates the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways and synergistically induces apoptosis in human acute leukemia cells through a mechanism that involves flavopiridol-mediated XIAP downregulation (107). Similarly, roscovitine and TRAIL demonstrate synergistic cytotoxicity in multiple leukemia and lymphoma cell lines and primary cells (108).

Co-treatment of human acute leukemia cells with the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002 and flavopiridol, roscovitine or CGP74514A resulted in a marked decrease in Akt phosphorylation and striking potentiation of mitochondrial damage and apoptosis, accompanied by diminished Bad phosphorylation, induction of Bcl-2 cleavage, and down-regulation of XIAP and Mcl-1 (109). Very similar findings have been reported in MCL cells (110). Most recently, it has been shown that killing by the PI3Kδ inhibitor GS-1101 (CAL-101) is cell-cycle dependent, and that induction of early G1 arrest by PD 0332991 sensitizes proliferating MCL cells to selective PI3Kδ inhibition (111).

Flavopiridol and lenalidomide have been combined in a phase I clinical trial in CLL (112). The combination was well tolerated without increased risks of TLS or tumor flare, with significant activity in patients with bulky, cytogenetically high-risk CLL. Preclinical studies indicate that both lenalidomide (113) and bortezomib (114, 115) synergize with PD 0332991 to kill MM cells via loss of IRF-4. A regimen of PD 0332991, 100 mg daily on days 1-12 of a 21-day cycle, combined with bortezomib 1 mg/m2 and dexamethasone 20 mg, administered on days 8, 11, 15 and 18, demonstrated encouraging anti-tumor activity in heavily pre-treated MM patients in a phase I trial (116) and is currently undergoing phase II evaluation (117).

8. Expert Opinion

Dysregulation of cell cycle progression in transformed cells was one of the first “hallmarks of cancer” to be recognized, and this prompted intense interest in the development of CDKIs for cancer treatment. The premise underlying these efforts was that the disordered cell cycle characteristic of neoplastic cells would render them more vulnerable than their normal counterparts to further cell cycle disruption, thereby providing a theoretical basis for selectivity. Indeed, numerous pre-clinical studies have shown that interference with cell cycle regulation represents one of the most potent inducers of apoptosis. Over the last two decades, the CDKI field has undergone a dramatic evolution due in large part to two factors: rapidly emerging insights into the factors regulating the cell cycle, and a growing appreciation of the implications of CDK inhibition for processes other than those specifically related to cell cycle regulation. Furthermore, structure-based drug design has allowed the development of considerably more potent and specific CDKIs than were previously available. The current challenge for CDKI development will be to gain formal approval of CDKIs, either as single agents or in combination with either conventional genotoxic or other targeted agents. Recent findings involving flavopiridol (e.g., in CLL and AML) and PD0332991 (in mantle cell lymphoma) suggest that this goal may be eminently feasible (see below).

One of the challenges facing this field has been translating promising pre-clinical findings involving CDKIs and into the clinical arena. For example, flavopiridol, the first CDKI to enter the clinic, displayed dramatic activity pre-clinically when administered at sub-micromolar concentrations. However, its activity in humans has, until recently, been quite limited, possibly due to an unfavorable pharmacokinetic profile and off-target toxicities. Nevertheless, modification of the flavopiridol administration schedule suggests significant activity in at least some disorders (e.g., refractory CLL (54)), particularly when combined with other targeted agents (e.g., bortezomib) in MM or NHL (101). Moreover, combining flavopiridol with genotoxic chemotherapy has recently shown significant promise in AML (84) and in advanced sarcomas (118). Finally, the CDK4/6 inhibitor PD0332991 has shown promising single-agent activity in mantle cell lymphoma (79), which may be further improved with combination strategies.

A critical issue for the development of CDKIs is whether their anti-neoplastic activity stems from CDK inhibition, inhibition of other targets, or a combination of these activities. For example, CDKIs that target CDK7 and/or 9 act as transcriptional repressors through inhibition of the pTEFb transcriptional regulatory complex, and down-regulate multiple short-lived proteins (e.g., Mcl-1) that are essential for the survival of malignant hematopoietic cells. It is entirely possible that in some settings, transcriptional repression may represent the primary mechanism by which such agents trigger neoplastic cell death. A key question, then, is whether the inhibitory effects of such agents on cell cycle progression contribute to lethality under these circumstances. In addition, it will be critical to determine whether such actions can be recapitulated in patients in vivo. Resolution of these issues could have a major impact on whether future developmental efforts should focus on more specific CDKIs, or more broadly active agents which display additional activities, e.g., inhibition of transcription. In this context, agents (e.g., dinaciclib) targeting CDK1, the only CDK sufficient for mammalian cell cycle progression (33), in addition to transcriptional CDKs, may prove promising. In addition, it is interesting that certain specific CDK4/6 inhibitors (e.g., PD0332991), while exerting only cytostatic activities toward malignant hematopoietic cells in pre-clinical studies, have shown promising results when combined with other agents (e.g., bortezomib) pre-clinically and in clinical trials.

One of the more rapidly advancing areas involves elucidation of the mechanisms by which CDKs contribute to DNA repair processes. For example, recent studies have implicated CDKs in both homologous recombination as well as non-homologous end-joining-related repair. These findings have obvious implications for the mechanisms by which CDKIs might interact with standard genotoxic agents, but could influence their interactions with other targeted agents as well. In this context, recent studies have suggested that solid tumor (e.g. breast cancer) cells displaying defects in DNA repair (e.g., expressing mutant BRCA1) may be particularly susceptible to CDK disruption (41, 42). It is possible that malignant hematopoietic cells exhibiting analogous defects might show similar susceptibility to CDKIs.

A key question involves the optimal approach to the development of CDKIs. One approach involves identifying genetic signatures that will predict susceptibility to these agents. For example, transcriptional repressive CDKIs (e.g., flavopiridol) have been used to target malignancies (e.g., multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma) that depend upon a protein (e.g., Mcl-1) shown to be down-regulated by such agents in pre-clinical studies. However, the theoretical possibility exists that CDKIs, as in the case of other targeted agents, may have limited single-agent activity; instead, they may best function as response modulators of other (conventional or targeted) agents. In view of the large body of pre-clinical data demonstrating synergistic potentiation of the activity of genotoxic agents by CDKIs, it is likely that these efforts will continue with newer-generation CDKIs. It is possible that the enhanced potency, specificity, and selectivity of these agents may improve upon results to date with older agents. Nevertheless, it will still be necessary to demonstrate that enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of such regimens will be accompanied by a net improvement in the therapeutic index. Finally, a third approach involves the rational combination of new-generation CDKIs with other targeted agents. In support of this strategy, multiple studies have identified synergistic regimens combining CDKIs with HDAC or proteasome inhibitors, or BH3 mimetics, particularly in malignant hematopoietic cells. The ultimate success of such approaches may depend upon an answer to the important theoretical question of whether combining two agents, neither of which may be individually active in a particular malignancy, can result in tangible therapeutic efficacy.

With respect to the immediate future of CDKIs, the most challenging questions to answer will include: a) are activities other than CDK inhibition most relevant for potential anti-cancer efficacy? b) will highly specific or more promiscuous CDKIs prove most effective in the clinic? c) will pharmacokinetic factors determine whether the CDK or other inhibitory actions of these agents can be recapitulated in patients in vivo? d) will single-agent CDKI activity be necessary for combination regimen efficacy? e) will combinations with conventional or novel agents represent the best strategy? Of the most newly described activities of CDKIs, disruption of DNA repair events may prove to be of great significance in the future. Of the more pleiotropically-acting CDKIs, dinaciclib appears to be particularly promising in view of its multiple actions and high potency, whereas of the more specific inhibitors, results with the CDK4/6 inhibitor PD0332991 are encouraging. Finally, given the rapid development of agents that target diverse survival signaling pathways, the opportunities for rational combination strategies involving CDKIs are virtually limitless. Hopefully, these considerations will lead to formal approval of one or more CDKIs in hematologic (and potentially epithelial) malignancies in the near future.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Yun Dai, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Internal Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA for kindly providing Figure 1, which was subsequently modified by the authors.

Grant Support: This work was supported in part by the following awards to Dr. Grant: R01 CA093738, R01 CA167708, P50 CA130805, P50 CA142509, RC2 CA148431 from the National Institutes of Health, and an award from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. Mar. 2009;9(3):153–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Apr 10;24(11):1770–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah MA, Schwartz GK. Cell cycle-mediated drug resistance: An emerging concept in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001 Aug;7(8):2168–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz GK, Shah MA. Targeting the cell cycle: A new approach to cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Dec 20;23(36):9408–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wesierska-Gadek J, Maurer M, Zulehner N, Komina O. Whether to target single or multiple CDKs for therapy? that is the question. J Cell Physiol. 2011 Feb;226(2):341–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6*.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: A critical decision in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001 Dec;1(3):222–31. doi: 10.1038/35106065. [An excellent, comprehensive review of the importance of the cell cycle and its regulation in cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer PM, Gianella-Borradori A. Recent progress in the discovery and development of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005 Apr;14(4):457–77. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirose Y, Ohkuma Y. Phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II plays central roles in the integrated events of eucaryotic gene expression. J Biochem. 2007 May;141(5):601–8. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koumenis C, Giaccia A. Transformed cells require continuous activity of RNA polymerase II to resist oncogene-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997 Dec;17(12):7306–16. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scrace SF, Kierstan P, Borgognoni J, Wang LZ, Denny S, Wayne J, et al. Transient treatment with CDK inhibitors eliminates proliferative potential even when their abilities to evoke apoptosis and DNA damage are blocked. Cell Cycle. 2008 Dec 15;7(24):3898–907. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Chen YN, Sharma SK, Ramsey TM, Jiang L, Martin MS, Baker K, et al. Selective killing of transformed cells by cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Apr 13;96(8):4325–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4325. [Seminal work showing that malignant cells could be selectively targeted by CDKIs, thereby largely sparing normal cells.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan J, Yan R, Kramer A, Eckerdt F, Roller M, Kaufmann M, et al. Cyclin B1 depletion inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human tumor cells. Oncogene. 2004 Jul 29;23(34):5843–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13**.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Proliferation of cancer cells despite CDK2 inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2003 Mar;3(3):233–45. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00053-9. [Original work demonstrating the redundancy (non-essential nature) of CDK2 for malignant cell proliferation.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Glaser SP, Lee EF, Trounson E, Bouillet P, Wei A, Fairlie WD, et al. Anti- apoptotic mcl-1 is essential for the development and sustained growth of acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Dev. 2012 Jan 15;26(2):120–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.182980.111. [Landmark study elegantly demonstrating that Mcl-1 is more critical to the development and maintenance of AML than Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michels J, O'Neill JW, Dallman CL, Mouzakiti A, Habens F, Brimmell M, et al. Mcl-1 is required for Akata6 B-lymphoma cell survival and is converted to a cell death molecule by efficient caspase-mediated cleavage. Oncogene. 2004 Jun 17;23(28):4818–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Zhang B, Gojo I, Fenton RG. Myeloid cell factor-1 is a critical survival factor for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002 Mar 15;99(6):1885–93. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1885. [The first report of the critical role of Mcl-1 in the survival of multiple myeloma cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.MacCallum DE, Melville J, Frame S, Watt K, Anderson S, Gianella-Borradori A, et al. Seliciclib (CYC202, R-roscovitine) induces cell death in multiple myeloma cells by inhibition of RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription and down-regulation of mcl-1. Cancer Res. 2005 Jun 15;65(12):5399–407. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0233. [One of the first studies to demonstrate transcriptional down-regulation of Mcl-1 by seliciclib as the mechanism of induction of apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Raje N, Kumar S, Hideshima T, Roccaro A, Ishitsuka K, Yasui H, et al. Seliciclib (CYC202 or R-roscovitine), a small-molecule cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, mediates activity via down-regulation of mcl-1 in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005 Aug 1;106(3):1042–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0320. [One of the first studies to demonstrate transcriptional down-regulation of Mcl-1 by seliciclib as the mechanism of induction of apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wuilleme-Toumi S, Robillard N, Gomez P, Moreau P, Le Gouill S, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. Mcl-1 is overexpressed in multiple myeloma and associated with relapse and shorter survival. Leukemia. 2005 Jul;19(7):1248–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen R, Wierda WG, Chubb S, Hawtin RE, Fox JA, Keating MJ, et al. Mechanism of action of SNS-032, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009 May 7;113(19):4637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-190256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Chen S, Dai Y, Harada H, Dent P, Grant S. Mcl-1 down-regulation potentiates ABT-737 lethality by cooperatively inducing bak activation and bax translocation. Cancer Res. 2007 Jan 15;67(2):782–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3964. [ Demonstrated synergistic induction of apoptosis in human leukemia cells by the combination of CDKI-induced Mcl-1 down-regulation and pharmacologic antagonism of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL function.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson DM, Joseph B, Hillion J, Segal J, Karp JE, Resar LM. Flavopiridol induces BCL-2 expression and represses oncogenic transcription factors in leukemic blasts from adults with refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011 Oct;52(10):1999–2006. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.591012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruse U, Pallasch CP, Bantscheff M, Eberhard D, Frenzel L, Ghidelli S, et al. Chemoproteomics-based kinome profiling and target deconvolution of clinical multi-kinase inhibitors in primary chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2011 Jan;25(1):89–100. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai Y, Hamm TE, Dent P, Grant S. Cyclin D1 overexpression increases the susceptibility of human U266 myeloma cells to CDK inhibitors through a process involving p130-, p107- and E2F-dependent S phase entry. Cell Cycle. 2006 Feb;5(4):437–46. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry DW, Harvey PJ, Keller PR, Elliott WL, Meade M, Trachet E, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004 Nov;3(11):1427–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts PJ, Bisi JE, Strum JC, Combest AJ, Darr DB, Usary JE, et al. Multiple roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Mar 21;104(6):476–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Cai D, Latham VM, Jr, Zhang X, Shapiro GI. Combined depletion of cell cycle and transcriptional cyclin-dependent kinase activities induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006 Sep 15;66(18):9270–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1758. [An elegant demonstration of the therapeutic importance of inhibiting both cell-cycle and transcriptional CDKs in malignant cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallis M, Burrows F, Whittall A, Seedhouse C, Boddy N, Russell NH. Effectiveness of transcriptional CDK inhibitors in targeting non-proliferating CD34+CD38- AML cells, ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011 Nov 18;118(21):3482. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson N, Shapiro GI. Cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) and the DNA damage response: Rationale for cdk inhibitor-chemotherapy combinations as an anticancer strategy for solid tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010 Nov;14(11):1199–212. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.525221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Maude SL, Enders GH. Cdk inhibition in human cells compromises chk1 function and activates a DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2005 Feb 1;65(3):780–6. [One of the earliest reports of the link between CDK inhibition and the DNA damage response network.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Yu B, Dalton WB, Yang VW. CDK1 regulates mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 during mitotic DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2012 Nov 1;72(21):5448–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2354. [Recent evidence for an important role for CDK1 in the regulation of checkpoint function.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Esashi F, Christ N, Gannon J, Liu Y, Hunt T, Jasin M, et al. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA2 as a regulatory mechanism for recombinational repair. Nature. 2005 Mar 31;434(7033):598–604. doi: 10.1038/nature03404. [Landmark study that elucidated in part the role of CDKs in DNA repair.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33**.Santamaria D, Barriere C, Cerqueira A, Hunt S, Tardy C, Newton K, et al. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature. 2007 Aug 16;448(7155):811–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06046. [Seminal work showing that mouse embryos can undergo organogenesis and survive to mid-gestation in the absence of all interphase CDKs.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ira G, Pellicioli A, Balijja A, Wang X, Fiorani S, Carotenuto W, et al. DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature. 2004 Oct 21;431(7011):1011–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huertas P, Cortes-Ledesma F, Sartori AA, Aguilera A, Jackson SP. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature. 2008 Oct 2;455(7213):689–92. doi: 10.1038/nature07215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, et al. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006 Jan;8(1):37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deans AJ, Khanna KK, McNees CJ, Mercurio C, Heierhorst J, McArthur GA. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 functions in normal DNA repair and is a therapeutic target in BRCA1-deficient cancers. Cancer Res. 2006 Aug 15;66(16):8219–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Zhu Y, Alvarez C, Doll R, Kurata H, Schebye XM, Parry D, et al. Intra-S-phase checkpoint activation by direct CDK2 inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Jul;24(14):6268–77. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6268-6277.2004. [An early demonstration of the link between CDK inhibition and cell cycle checkpoint activation, potentially serving as a basis for the rational combination of CDKIs and checkpoint abrogators.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Y, Ishimi Y, Tanudji M, Lees E. Human CDK2 inhibition modifies the dynamics of chromatin-bound minichromosome maintenance complex and replication protein A. Cell Cycle. 2005 Sep;4(9):1254–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wohlbold L, Merrick KA, De S, Amat R, Kim JH, Larochelle S, et al. Chemical genetics reveals a specific requirement for Cdk2 activity in the DNA damage response and identifies Nbs1 as a Cdk2 substrate in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2012 Aug;8(8):e1002935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.Johnson N, Cai D, Kennedy RD, Pathania S, Arora M, Li YC, et al. Cdk1 participates in BRCA1-dependent S phase checkpoint control in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2009 Aug 14;35(3):327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.036. [An important study identifying BRCA1 as a link between CDK1 and cell cycle checkpoint function.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson N, Li YC, Walton ZE, Cheng KA, Li D, Rodig SJ, et al. Compromised CDK1 activity sensitizes BRCA-proficient cancers to PARP inhibition. Nat Med. 2011 Jun 26;17(7):875–82. doi: 10.1038/nm.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Radomska HS, Alberich-Jorda M, Will B, Gonzalez D, Delwel R, Tenen DG. Targeting CDK1 promotes FLT3-activated acute myeloid leukemia differentiation through C/EBPalpha. J Clin Invest. 2012 Aug 1;122(8):2955–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI43354. [Recent demonstration of a new function for CDK1 in FLT3-mutated AML.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahoney E, Lucas DM, Gupta SV, Wagner AJ, Herman SE, Smith LL, et al. ER stress and autophagy: New discoveries in the mechanism of action and drug resistance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. Blood. 2012 Aug 9;120(6):1262–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Wang H, Kim J, Pihan G, Boussiotis V. The cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor (R)-roscovitine prevents alloreactive T cell clonal expansion and protects against acute GvHD. Cell Cycle. 2009 Jun 1;8(11):1794. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parker BW, Kaur G, Nieves-Neira W, Taimi M, Kohlhagen G, Shimizu T, et al. Early induction of apoptosis in hematopoietic cell lines after exposure to flavopiridol. Blood. 1998 Jan 15;91(2):458–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lam LT, Pickeral OK, Peng AC, Rosenwald A, Hurt EM, Giltnane JM, et al. Genomic-scale measurement of mRNA turnover and the mechanisms of action of the anti-cancer drug flavopiridol. Genome Biol. 2001;2(10):RESEARCH0041. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-10-research0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48**.Chao SH, Price DH. Flavopiridol inactivates P-TEFb and blocks most RNA polymerase II transcription in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001 Aug 24;276(34):31793–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102306200. [Seminal work elucidating the mechanisms underlying inhibition of transcription by flavopiridol.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Decker RH, Dai Y, Grant S. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells (U937) through the mitochondrial rather than the receptor-mediated pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2001 Jul;8(7):715–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byrd JC, Peterson BL, Gabrilove J, Odenike OM, Grever MR, Rai K, et al. Treatment of relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia by 72-hour continuous infusion or 1-hour bolus infusion of flavopiridol: Results from cancer and leukemia group B study 19805. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Jun 1;11(11):4176–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Geyer SM, Fitch TR, Fenton RG, et al. Flavopiridol in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: A phase 2 trial with clinical and pharmacodynamic end-points. Haematologica. 2006 Mar;91(3):390–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kouroukis CT, Belch A, Crump M, Eisenhauer E, Gascoyne RD, Meyer R, et al. Flavopiridol in untreated or relapsed mantle-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study of the national cancer institute of canada clinical trials group. J Clin Oncol. 2003 May 1;21(9):1740–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flinn IW, Byrd JC, Bartlett N, Kipps T, Gribben J, Thomas D, et al. Flavopiridol administered as a 24-hour continuous infusion in chronic lymphocytic leukemia lacks clinical activity. Leuk Res. 2005 Nov;29(11):1253–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54**.Byrd JC, Lin TS, Dalton JT, Wu D, Phelps MA, Fischer B, et al. Flavopiridol administered using a pharmacologically derived schedule is associated with marked clinical efficacy in refractory, genetically high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):399–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-020735. [The first demonstration of robust single-agent activity of flavopiridol in poor-risk patients with a hematologic malignancy when administered by a pharmacokinetically driven “hybrid” schedule.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phelps MA, Lin TS, Johnson AJ, Hurh E, Rozewski DM, Farley KL, et al. Clinical response and pharmacokinetics from a phase 1 study of an active dosing schedule of flavopiridol in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009 Mar 19;113(12):2637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56**.Lin TS, Ruppert AS, Johnson AJ, Fischer B, Heerema NA, Andritsos LA, et al. Phase II study of flavopiridol in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrating high response rates in genetically high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec 10;27(35):6012–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6944. [Confirmation of high efficacy of flavopiridol as a single agent in CLL when administered in a “hybrid” fashion.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blum W, Phelps MA, Klisovic RB, Rozewski DM, Ni W, Albanese KA, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of a novel schedule of flavopiridol in relapsed or refractory acute leukemias. Haematologica. 2010 Jul;95(7):1098–105. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones JA, Kraut EH, Deam D, Byrd JC, Grever MR. Hematologic improvement after flavopiridol treatment of pentostatin and rituximab refractory hairy cell leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012 Mar;53(3):490–1. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.600484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Josefsberg Ben-Yehoshua L, Beider K, Shimoni A, Ostrovsky O, Samookh M, Peled A, et al. Characterization of cyclin E expression in multiple myeloma and its functional role in seliciclib-induced apoptotic cell death. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lacrima K, Rinaldi A, Vignati S, Martin V, Tibiletti MG, Gaidano G, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor seliciclib shows in vitro activity in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007 Jan;48(1):158–67. doi: 10.1080/10428190601026562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Misra RN, Xiao HY, Kim KS, Lu S, Han WC, Barbosa SA, et al. N-cycloalkylamino)acyl-2-aminothiazole inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2. N-[5-[[[5-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2-oxazolyl]methyl]thio]-2-thiazolyl]-4- piperidinecarboxamide (BMS-387032), a highly efficacious and selective antitumor agent. J Med Chem. 2004 Mar 25;47(7):1719–28. doi: 10.1021/jm0305568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen R, Chubb S, Cheng T, Hawtin RE, Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Responses in mantle cell lymphoma cells to SNS-032 depend on the biological context of each cell line. Cancer Res. 2010 Aug 15;70(16):6587–97. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conroy A, Stockett DE, Walker D, Arkin MR, Hoch U, Fox JA, et al. SNS-032 is a potent and selective CDK 2, 7 and 9 inhibitor that drives target modulation in patient samples. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009 Sep;64(4):723–32. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tong WG, Chen R, Plunkett W, Siegel D, Sinha R, Harvey RD, et al. Phase I and pharmacologic study of SNS-032, a potent and selective Cdk2, 7, and 9 inhibitor, in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jun 20;28(18):3015–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu Y, Chen C, Sun X, Shi X, Jin B, Ding K, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 7/9 inhibitor SNS-032 abrogates FIP1-like-1 platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha and bcr-abl oncogene addiction in malignant hematologic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Apr 1;18(7):1966–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walsby E, Lazenby M, Pepper C, Burnett AK. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor SNS-032 has single agent activity in AML cells and is highly synergistic with cytarabine. Leukemia. 2011 Mar;25(3):411–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parry D, Guzi T, Shanahan F, Davis N, Prabhavalkar D, Wiswell D, et al. Dinaciclib (SCH 727965), a novel and potent cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010 Aug;9(8):2344–53. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Neale G, Keir ST, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor SCH 727965 (dinaciclib) by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012 Feb 7; doi: 10.1002/pbc.24073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson AJ, Yeh YY, Smith LL, Wagner AJ, Hessler J, Gupta S, et al. The novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH727965) promotes apoptosis and abrogates microenvironmental cytokine protection in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2012 Dec;26(12):2554–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sadowska M, Muvarak N, Lapidus RG, Sausville EA, Bannerji R, Gojo I. Single agent activity of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in acute myeloid and lymphoid leukemia cells. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2010 Nov 19;116(21):3981. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baiocchi RA, Flynn JM, Jones JA, Blum KA, Hofmeister CC, Poon J, et al. Early evidence of anti-lymphoma activity of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in heavily pre-treated low grade lymphoma and diffuse large cell lymphoma patients. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2010 Nov 19;116(21):3966. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flynn JM, Jones JA, Andritsos L, Blum KA, Johnson AJ, Hessler J, et al. Phase I study of the CDK inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory CLL. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011 Jun 09;29(15_suppl):6623. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gojo I, Walker A, Cooper M, Feldman EJ, Padmanabhan S, Baer MR, et al. Phase II study of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH 727965) in patients with advanced acute leukemias. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2010 Nov 19;116(21):3287. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumar SK, LaPlant BR, Chng WJ, Zonder JA, Callander N, Roy V, et al. Phase 1/2 trial of a novel CDK inhibitor dinaciclib (SCH727965) in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma demonstrates encouraging single agent activity. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2012 Nov 16;120(21):76. [Google Scholar]

- 75*.Baughn LB, Di Liberto M, Wu K, Toogood PL, Louie T, Gottschalk R, et al. A novel orally active small molecule potently induces G1 arrest in primary myeloma cells and prevents tumor growth by specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. Cancer Res. 2006 Aug 1;66(15):7661–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1098. [One of the earliest reports of promising preclinical activity of the CDK4/6-specific inhibitor, PD0332991.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feng R, Huang X, Coulton L, Raeve HD, DiLiberto M, Ely S, et al. Targeting CDK4/CDK6 impairs osteoclast progenitor pool expansion and blocks osteolytic lesion development in multiple myeloma. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2009 Dec 11;114(22):298. [Google Scholar]

- 77*.Marzec M, Kasprzycka M, Lai R, Gladden AB, Wlodarski P, Tomczak E, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma cells express predominantly cyclin D1a isoform and are highly sensitive to selective inhibition of CDK4 kinase activity. Blood. 2006 Sep 1;108(5):1744–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016634. [An early report of the preclinical activity of the specific CDK4/6 inhibitor, PD0332991, in mantle cell lymphoma, a disease characterized by cyclin D1 overexpression.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang L, Wang J, Blaser BW, Duchemin AM, Kusewitt DF, Liu T, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of CDK4/6: Mechanistic evidence for selective activity or acquired resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007 Sep 15;110(6):2075–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-071266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79*.Leonard JP, LaCasce AS, Smith MR, Noy A, Chirieac LR, Rodig SJ, et al. Selective CDK4/6 inhibition with tumor responses by PD0332991 in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012 May 17;119(20):4597–607. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388298. [A recent report of promising clinical efficacy of PD0332991 in patients with mantle cell lymphoma.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80*.Bible KC, Kaufmann SH. Cytotoxic synergy between flavopiridol (NSC 649890, L86-8275) and various antineoplastic agents: The importance of sequence of administration. Cancer Res. 1997 Aug 15;57(16):3375–80. [One of the earliest demonstrations of the sequence-dependent nature of the synergism between flavopiridol and cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O'Connor DS, Wall NR, Porter AC, Altieri DC. A p34(cdc2) survival checkpoint in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002 Jul;2(1):43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82*.Karp JE, Ross DD, Yang W, Tidwell ML, Wei Y, Greer J, et al. Timed sequential therapy of acute leukemia with flavopiridol: In vitro model for a phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Jan;9(1):307–15. [The laboratory findings upon which “timed sequential therapy” with flavopiridol and conventional cytotoxic agents in AML is based.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karp JE, Passaniti A, Gojo I, Kaufmann S, Bible K, Garimella TS, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of flavopiridol followed by 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine and mitoxantrone in relapsed and refractory adult acute leukemias. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Dec 1;11(23):8403–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]