Summary

The protein density and arrangement of subunits of a complete, 31-protein, RNA polymerase II (pol II) transcription pre-initiation complex (PIC) were determined by cryo-electron microscopy and a combination of chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. The PIC showed a marked division in two parts, one containing all the general transcription factors (GTFs), and the other pol II. Promoter DNA was associated only with the GTFs, suspended above the pol II cleft and not in contact with pol II. This structural principle of the PIC underlies its conversion to a transcriptionally active state; the PIC is poised for the formation of a transcription bubble and descent of the DNA into the pol II cleft.

INTRODUCTION

Sixty proteins assemble in a three million Dalton complex at every pol II promoter, prior to every round of transcription (1, 2). About half of these proteins, some thirty in number (the subunits of pol II and the GTFs) form a pre-initiation complex (PIC) that can recognize a minimal (TATA-box) promoter, select a transcription start site, and synthesize a nascent transcript. The remaining proteins are needed for recognition of an extended promoter (TAF complex) and for the regulation of transcription (Mediator complex) (3). Orchestration of the initiation process depends on the organization of components of the PIC. We report here on the 3-D arrangement of the thirty proteins of the PIC.

Biochemical studies have identified functions of several PIC proteins (1). TBP, a subunit of the general transcription factor TFIID, binds and bends TATA-box DNA (4). TFIIB brings the TBP-promoter DNA complex to pol II near the active center cleft (5). TFIIH, an eleven-protein complex, has multiple catalytic activities, including an ATPase/helicase, Ssl2 (6), that melts promoter DNA to form the so-called “transcription bubble,” and a protein kinase (7) whose action upon the C-terminal domain of pol II controls association with Mediator and other accessory proteins (8). Functional roles of additional GTFs, TFIIA, TFIIE, and TFIIF, are less well established.

Structural information on the PIC is incomplete. X-ray structures have been determined for pol II (9, 10), pol II-DNA complexes (11), a pol II-TFIIB complex (12–14), and a TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex (15). Structures at much lower resolution have been determined by electron microscopy of negatively stained proteins for a pol II-TFIIF complex (16), for TFIIE (17), and for TFIIH (18–20). The advance reported here, structural analysis of a fully assembled PIC, was made possible by three technical developments. First, improved methods of preparation of the GTFs (21) and their assembly with pol II resulted in abundant, homogeneous, PIC (22). Secondly, upon structural analysis by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), it emerged that conformational heterogeneity was an impediment to image processing of the PIC. An algorithm was developed for classifying images on the basis of conformational state, enabling averaging and 3-D reconstruction (23, 24). Finally, spatial proximities of proteins in the PIC were determined by cross-linking and mass spectroscopy (XL-MS) (25–27). A computational approach was devised for combining information from cryo-EM and XL-MS to arrive at a complete 3-D map of the protein components of the PIC. Abbreviated Results and Discussion follow. Complete Results, Discussion, and Material and Methods are presented in Supplementary Materials.

Cryo-EM and 3-D reconstruction

Pol II and GTFs, isolated from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, were combined with a fragment of HIS4 promoter DNA (−81/+1) and sedimented in a glycerol gradient as described (Fig. S1) (22). Two forms of the PIC were prepared in this way: one, denoted complete PIC, contained all GTFs (TFIIA, TFIIB, TBP, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH) and, in addition, the transcription elongation factor TFIIS, implicated by genetic analysis in the initiation of transcription in vivo (28) and with nuclear extract in vitro (29); a second form, denoted PIC-ΔTFIIK, was identical with the first, except for the removal of a three-subunit module of TFIIH termed TFIIK (within which resides the protein kinase mentioned above). Partial complexes, lacking one or more of the GTFs, are unstable and dissociate upon handling. It is uncertain whether partial complexes adopt defined structures. Only the complete PIC (or PIC-ΔTFIIK) exhibited a barrier to digestion by exonuclease III from the downstream end of the DNA. No barrier was observed when any one of the GTFs was omitted (Fig. S1). Even the complete PIC tended to dissociate during specimen preparation for cryo-EM, and glutaraldehyde was included in the glycerol gradient (30) for stabilization. Images were acquired on a TEM equipped with a field emission gun under low-dose conditions (10–15 e−/Å2) (Fig. S2): 433,916 images of single particles of complete PIC; and 305,160 images of PIC-ΔTFIIK.

Image processing was performed with SIMPLE (24), a program package for the analysis of asymmetrical and heterogeneous single particles that requires no prior knowledge of the structure, no search model, and therefore does not introduce model bias. SIMPLE addresses the problem of heterogeneity by a “Fourier common lines” approach (23). Analysis with SIMPLE revealed two predominant states in both forms of the PIC. Following refinement, the resolution of the density maps was highest for complete PIC (16 Å by the Fourier shell criterion). The maps measured 240 × 170 × 150 Å. In both forms of the PIC, the maps were clearly divided in two parts, confirmed by automatic segmentation, and termed P-lobe and G-lobe (Fig. 1). An excellent fit of the pol II X-ray structure (contoured at 20 Å resolution; Fig. 1B) to the P-lobe served to validate the segmentation and the reconstructions.

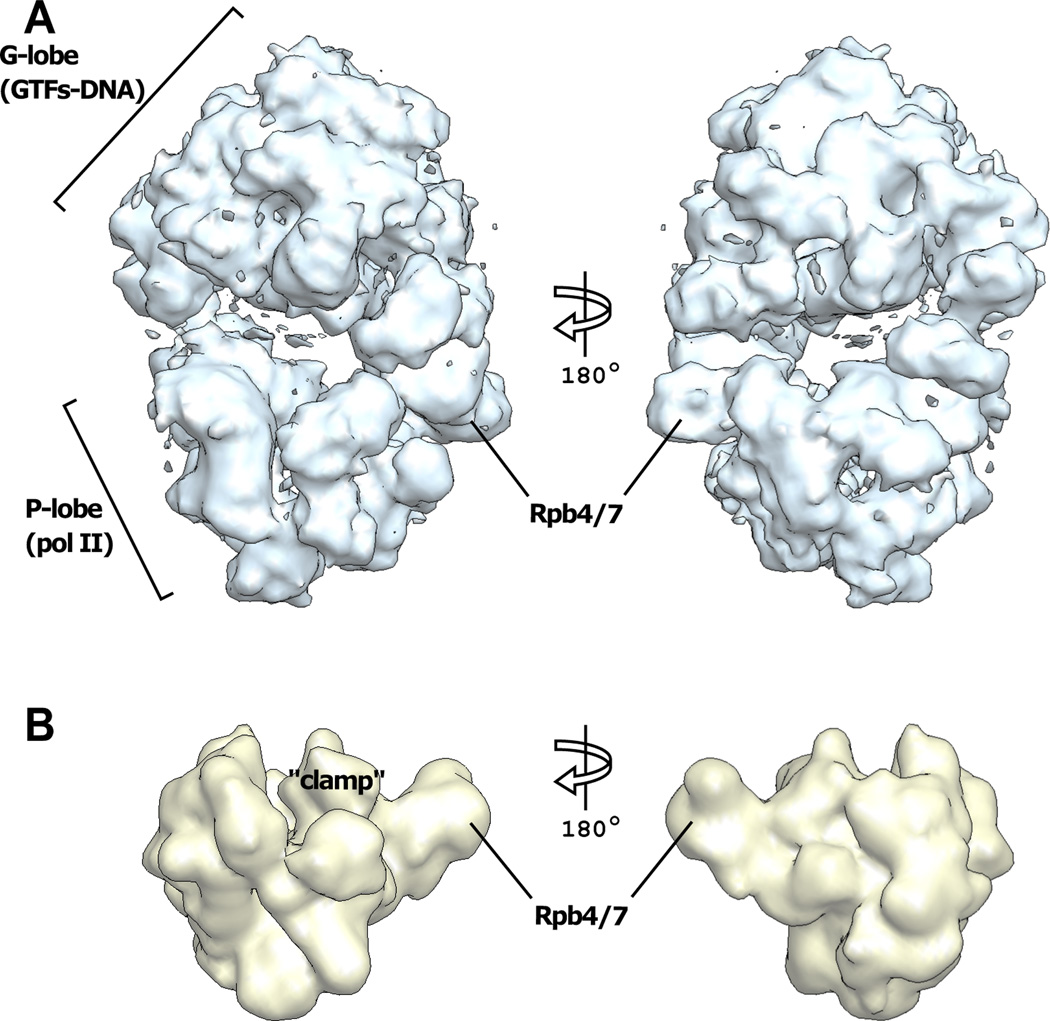

Fig. 1. Cryo-EM structure of the 32-protein PIC including TFIIS (PIC).

(A) Front (left panel) and back (right panel) views of the most populated state of the PIC. (B) Low-pass filtered (20 Å) 12-subunit pol II (45) is viewed in the same orientations as in (A). The mobile “clamp” domain of pol II (10) and the dissociable subunits Rpb4/7 are indicated.

Segmentation of electron density: location of GTFs and DNA

Manual fitting of the pol II structure to the P-lobe was optimized with computational refinement. A difference map calculated between the pol II structure and the P-lobe revealed one extra region of density in the P-lobe, adjacent to the Rpb4/7 subunits, which may be due to the C-terminal domain (CTD) of Rpb1 (Fig. S3). The G-lobe showed similarity in size and shape to EM structures of negatively stained complete (“holo”) TFIIH (20) (Fig. 2A, B). On this basis, approximate locations of Rad3 and Ssl2 subunits of TFIIH were identified (see Fig. 2D for color code to all subunits of GTFs), and TFIIK was placed in close proximity to its substrate, the CTD. The location of TFIIK was confirmed by its removal from the PIC: the density attributed to TFIIK was absent from structures of PIC-ΔTFIIK (Fig. 2C).

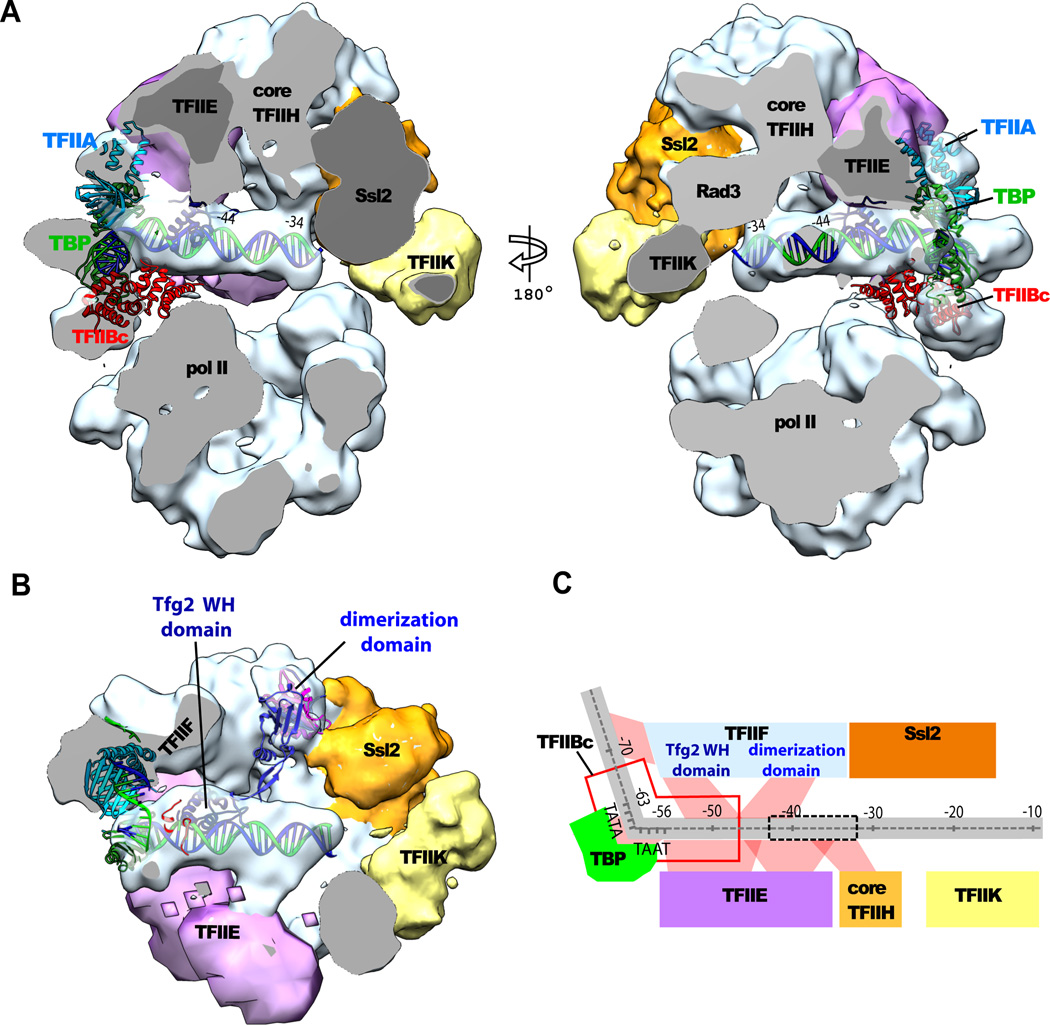

Fig. 2. Location of TFIIH in the PIC.

(A) Front (left panel) and side (right panel) views of the PIC with suggested assignments based on comparison with (B). Core (Tfb1–4) and Rad3 are gold, Ssl2 is orange, TFIIK is lime yellow. The extra density marked by * may be due to the C-terminal domain (CTD) of Rpb1. (B) Molecular envelope from EM and 3D reconstruction of negatively stained TFIIH(20), viewed in the same orientation as the right panel of (A). (C) Front (left panel) and side (right panel) views of the PIC lacking TFIIK (PIC-ΔTFIIK). Dashed ellipses indicate the location of the density, labeled TFIIK in (A), that is not observed. (D) SDS-PAGE of peak glycerol gradient fractions of PIC (left) and PIC–ΔTFIIK (right). Rpb10, Rpb12, and Tfb5 are not seen due to their low molecular weights. The same color scheme is used in all figures.

The EM maps of the complete PIC also contained density attributable to TBP, TFIIA, TFIIB, and promoter DNA (Fig. 3). A crystallographic model (12–14) of a “minimal” PIC (pol II-TBP-TFIIB-DNA complex) could be docked to the EM density with only slight deviations in the DNA path. The DNA density contacted G-lobe density, 10–20 bp downstream of the TATA box, and merged with Ssl2 density at the downstream end (Fig. 3A, B). Because roughly cylindrical density for DNA could be seen between the upstream and downstream points of contact, it was essentially free in this region.

Fig. 3. Locations of general transcription factors and promoter DNA in the PIC.

(A) The PIC structure, sectioned to reveal the DNA in the center (cut surfaces are gray). The structure on the left side of Fig. 1A was rotated 60° counterclockwise about the vertical axis (left) or 120° clockwise (right). Subunits of TFIIE and TFIIH (core TFIIH and its Rad3 component, Ssl2, and TFIIK) are indicated. Atomic models of the TBP (green)-TFIIBC(red)-TATA-box complex (15) and TFIIA (cyan) (32) were fitted to the cryo-EM density and displayed as ribbon diagrams. The TATA box DNA was extended with straight B-form DNA with minor adjustments of the DNA path. (B) The underside of the G-lobe, viewed from bottom of left panel of (A) with the P-lobe removed. Atomic models of the Tfg1-Tfg2 dimerization domain (Tfg1 blue; Tfg2 magenta) and the winged helix (WH) domain of Tfg2 (navy blue) were located by protein-protein cross-linking and displayed as ribbon diagrams. (C) Schematic diagram of proximity relationships of promoter DNA (gray) and GTFs in the PIC. Positions in the DNA are numbered with respect to the first transcription start site of the HIS4 promoter. The TATA box spans positions from −63 to −56. Transcription bubble formed upon initial promoter melting is indicated by dashed box. Putative interactions are indicated by red shading.

Removal of density due to TBP, TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIIH and DNA from the G-lobe leaves residual density that may be attributed to TFIIE and TFIIF. The residual density was automatically segmented into regions of about 100 and 90 kDa, which were assigned to TFIIE and TFIIF, respectively (Fig. 4A), on the basis of additional evidence from protein-protein cross-linking described below. Together TFIIE and TFIIF would largely surround the DNA in the vicinity of the TATA box.

Fig. 4. Spatial restraints from cross-linking and mass spectrometry (XL-MS): domains of TFIIF.

(A) Front view (same as Fig. 1A) of the PIC showing only the EM densities for TFIIF (light blue) and TFIIE (light purple). Pol II domains (jaw-lobe, cyan; clamp, yellow; core, gray ; shelf, magenta), TFIIA (cyan), TFIIB (red), and TBP (green) are represented as backbone traces. Lysine residues of pol II and one of TBP that form cross-links to TFIIE and TFIIF are marked by van de Waals spheres and colored according to the subunit to which they are cross-linked (Tfg1, blue; Tfg2, magenta; TFIIE, purple; Ssl2, orange). If the cross-linked residue is absent from the model, then the closest structured residue (up to 3 residues away in the amino acid sequence) is shown in parentheses. (B) Schematic representation of cross-links (red dashed lines) involving Tfg1 and Tfg2, whose primary structures are depicted as boxes, with solid colors for regions of conserved folds. Only inter-subunit cross-links are shown. (C) Close-up view of models of the Tfg1-Tfg2 dimerization domain (Tfg1, blue; Tfg2, magenta) and the WH domain of Tfg2 (navy blue) oriented on the basis of the cross-links indicated (red dashed lines). Pol II is shown in surface representation with the same colors as in (A). The Tfg2 yeast-specific insertion loop (residues 139–211) also cross-links to the C-terminal region of Ssl2, located near K1217, 1246, and 1262 of Rpb1.

Cross-linking and mass spectrometry (XL-MS): locations of TFIIA, -B, -E, and -F

The proposed locations of the GTFs within the G-lobe, based on docking and automatic segmentation, were confirmed by XL-MS (25–27). For this purpose, the PIC was cross-linked with BS3, a bifunctional amino group reagent. Following protease digestion and mass-spectrometry, assignments of cross-linked peptides to observed ion masses were scored for significance as described (27). A total of 89 intermolecular and 136 intramolecular cross-links of high significance (less than 1.5% false-positive rate) were identified (Table S1, Fig. S7). Validation came from 73 cross-links between residues separated by distances known from crystal structures of pol II-TFIIB (14), pol II-TFIIS (31), and TFIIA-TBP-DNA (32). The Cα-Cα distances between such residues were less than 30 Å for 70 cross-links, less than 34 Å for two cross-links, and 60 Å for the remaining one. These numbers are in accord with previous studies showing that the Cα-Cα distance of residues bridged by BS3 are generally less than 30 Å, and in rare cases as much as 35Å (25, 27). The one cross-link of 60 Å is likely a wrong assignment, not unexpected given the 1.5% false-positive rate.

Cross-links involving the Tfg1-Tfg2 dimerization and the Tfg2 winged-helix (WH) domains of TFIIF were sufficient to locate these domains in the EM map (Fig. 3B). The “flexible arm” of Tfg1 and the “insertion loop” of Tfg2 (33) formed a pattern of crosslinks with residues in the Rpb2 subunit of pol II (K87, K344, K358, K426) that placed the dimerization domain adjacent to the Rpb2 “protrusion” and “jaw-lobe” domains (Fig. 4C). The location of the insertion loop is supported by cross-links to the C-terminal region of Ssl2, which penetrates the downstream end of the pol II cleft, as shown by cross-linking of this region of Ssl2 to Rpb1 residues K1217, 1246, and 1262 (Fig. 4A–C). The WH domain of Tfg2 also formed cross-links to the Toa2 subunit of TFIIA (K119), to TFIIB (K199), and to the Tfa2 subunit of TFIIE (Fig. 4B), that defined a unique location along the path of the DNA (Table S4). The resulting model is in excellent agreement with previous FeBABE cleavage mapping of protein-promoter DNA interaction in complexes formed in yeast nuclear extract (34).

Combination of XL-MS and cryo-EM: locations of TFIIE and TFIIH

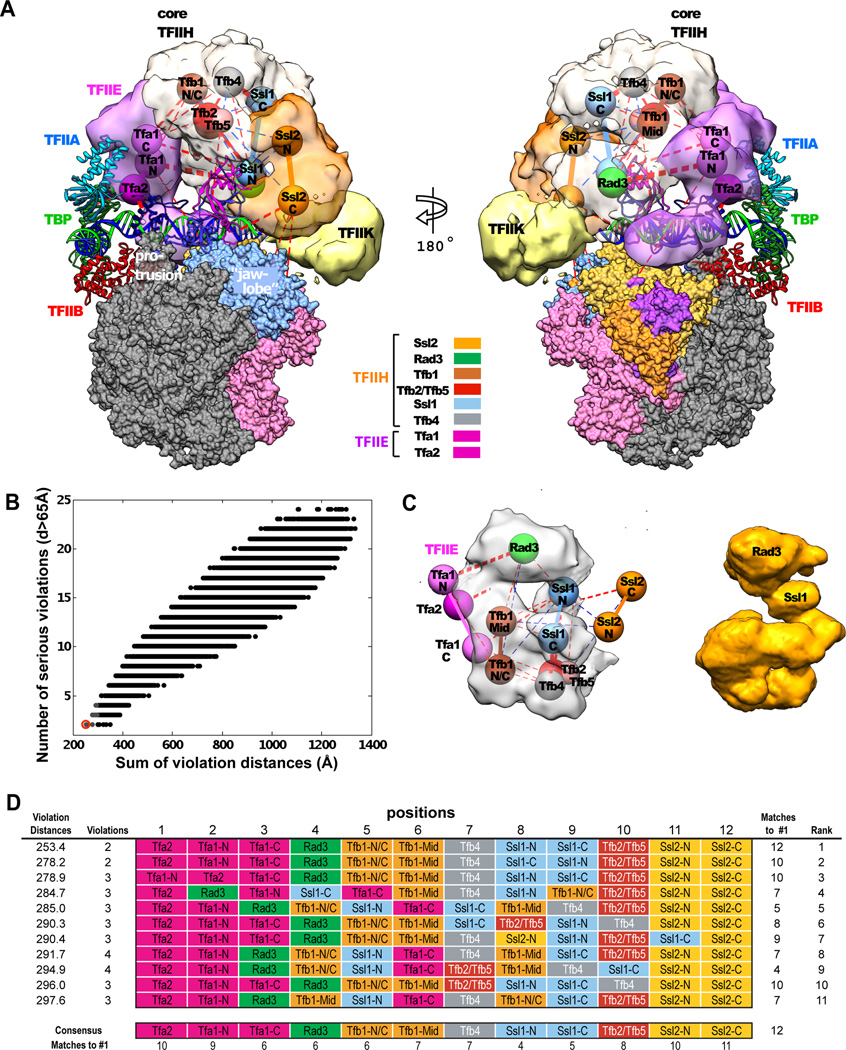

The two subunits of TFIIE and seven subunits of core TFIIH formed many cross-links with one another (Fig. S7). To interpret this information in terms of the EM map, we represented each subunit by one or two spheres (Fig. S12), depending on the mass of the subunit and the pattern of internal cross-links (a total of twelve spheres, see Supplementary Materials). Twelve locations for these spheres, spanning the EM density attributed to TFIIE and TFIIH (Fig. 5A, B), were chosen by an objective procedure: the first location was at the point of highest EM density, the next location was at the point of next highest density that was more than 35 Å from the first, and so forth. There are twelve factorial (480 million) different models that assign the twelve spheres to the twelve locations, and we assessed them exhaustively. We first discarded models in which two spheres belonging to the same protein were more than 45 Å apart, reducing the number of arrangements to half a million. We then evaluated the fit of a model to the pattern of cross-links on the basis of two measures: serious violation, defined by a pair of spheres located more than 65 Å apart in the model, for which a cross-link is nevertheless observed; and violation distance, defined as the excess over 40 Å between a pair of spheres in the model for which a cross-link is observed. These two measures were correlated over a wide range of values (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Combination of XL-MS and cryo-EM: TFIIE and TFIIH.

(A) Side views of PIC showing EM densities attributed to TFIIE (light purple) and TFIIH (core TFIIH, gray; Ssl2, orange; TFIIK, light yellow). Spheres for TFIIE, core TFIIH, and Ssl2 subunits are labeled according to the model that best fits the XL-MS data. Solid lines connect spheres belonging to the same subunit. Red dashed lines indicate inter-subunit cross-links in the PIC, with thicknesses proportional to the number of cross-links observed. Blue dashed lines indicate cross-links in holo-TFIIH only. The EM density for TFIIF is omitted for clarity. Other elements of the PIC are represented as in Fig. 4C. (B) Fit of various models of the subunit locations (scatter) to XL-MS data. Two measures of fit are plotted for each model: the number of cross-linked spheres that are more than 65 Å apart (y axis) and the sum of distances in excess of 40 Å between cross-linked spheres (x axis). The best-fitting model (red circle) is shown in panel A. (C) Comparison of the density for core TFIIH (left, gray) from panel A with the reconstructed volume of core TFIIH from EM of 2D crystals in stain (18) (right, light brown). Locations of TFIIE (three purple spheres) and Ssl2 (two orange spheres) from panel A are shown on the left as well. (D) Listing of the eleven best fitting models (gray scatter in B), detailing for each the assignments of the subunits to the twelve fixed positions in the electron density. Each row represents a different model, with the best-fitting model (panel A) listed at the top. The most frequently occurring subunit at each position (the consensus) is identical to that of the best-fitting model. The strength of the consensus (bottom row) is indicative of the confidence of subunit assignment.

The model with the smallest sum of violation distances (Fig. 5A) was identical to the consensus of the ten next best models at each location (Fig. 5D), and was the model returned most frequently by bootstrap analysis (Fig. S13). The locations of TFIIE and TFIIH, which were the same as those determined by automatic segmentation of the EM density. The size and shape of the region assigned to core TFIIH were closely similar to those of a structure determined by 2-D crystallography (18) (Fig. 5C). TFIIE extended across the surface of the G-lobe in proximity to the promoter DNA (Fig. 5A). Tfa1 and Tfa2 subunits of TFIIE (“Tfa1 N-term” and two WH domains of Tfa2) were cross-linked to each other immediately downstream of the TATA box (between DNA −54 and −44). “Tfa1 C-term” formed additional cross-links with all subunits of core TFIIH, reaching as far as Ssl1 (the N-terminal half, denoted “Ssl1 N”). Ssl1 N formed cross-links to all subunits of core TFIIH, consistent with its assignment in the 2-D crystal structure (18) to a central position, between Rad3 and the rest of the structure.

Discussion

This study has revealed a central principle of the PIC: the association of promoter DNA only with the GTFs and not with pol II. Promoter DNA is suspended above the pol II cleft, contacting three GTFs - TFIIB, TFIID (TBP subunit), and TFIIE - at the upstream end of the cleft (TATA box), and contacting TFIIH (Ssl2 helicase subunit) at the downstream end. In between, the DNA is free, available for action of the helicase, which untwists the DNA to introduce negative superhelical strain and thereby promote melting at a distance (35).

This principle of the PIC is a consequence of the rigidity of duplex DNA. The promoter duplex must follow a straight path, whereas bending through about 90° is required for binding in the pol II cleft (11). Only after melting can the DNA bend for entry in the cleft. Melting is thermally driven, induced by untwisting strain in the DNA above the cleft. A melted region is short-lived and must be captured by binding to pol II, which occurs rapidly enough because the DNA is positioned above the cleft. The GTFs therefore catalyze the formation of a stably melted region (transcription bubble) in two ways, by the introduction of untwisting strain (by the helicase) and by positioning promoter DNA.

Untwisting strain is distributed throughout the DNA above the pol II cleft, so melting may occur at any point, but only a melted region adjacent to TFIIB is stabilized by binding to pol II. The reason is again the rigidity of duplex DNA, and the requirement for a sharp bend adjacent to TFIIB to penetrate the pol II cleft. A single strand of DNA must extend from the point of contact with TFIIB, about 13 bp downstream of the TATA box (36, 37), through the binding site for the transcription bubble in pol II. TFIIB may also interact with the single strand to stabilize the bubble (14).

Our conclusions are based on results from both cryo-EM and XL-MS, which served to validate one another: segmentation and labeling of electron density, based on fitting pol II and other known structures, was consistent with all but two of 266 cross-links observed. Our PIC structure is also consistent with partial structural information from X-ray crystallography (pol II–TFIIB (12–14), pol II–TFIIS (31), TFIIA–TBP–TFIIB–DNA (15, 32), Tfb2–Tfb5 (38)), from NMR (Tfb1–Tfa1 (39), Tfa2–DNA (40)), and from EM (core and holo TFIIH (18) (20)). This consistency provides cross-validation, both supporting our PIC structure and establishing the relevance of the partial structural information. Further consistency with the results of FeBABE cleavage mapping of complexes formed in yeast nuclear extract (34) was mentioned above; the locations of proteins along the DNA in our PIC structure and those determined by FeBABE cleavage differ by no more than 5 bp. Our PIC structure also agrees with results of protein–DNA cross-linking in a reconstituted human transcription system (35); positions of TFIIE and TFIIH differ between the two studies by about 20 and 10bp. The location of Ssl2 in our structure, about 30 bp downstream from the TATA box (Fig. 3B, C), supports the proposal, made on the basis of previous DNA-protein cross-linking analysis, that helicase action torques the DNA to introduce untwisting strain and thereby to promote melting at a distance (35).

While this manuscript was in preparation, Nogales and coworkers reported EM structures of human PICs (41). The Nogales structures were produced from presumptive partial complexes by alignment of EM images to a structure of pol II as a search model, so they unavoidably include the pol II structure. Beyond pol II and two GTF polypeptides, TBP and TFIIB, there is little resemblance between the Nogales structures and ours (Figs. 6A–B, S13). The Nogales structures have no G-lobe (Fig. 6B), contain very little density for TFIIE (30 per cent of expected) and TFIIF (20 per cent), are inconsistent with the majority of the intermolecular cross-links involving TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH that we observed, and show a very different DNA path from our structure (Fig. 7). The Nogales structures do not reveal a complete PIC and are incorrect in several respects; the differences from our PIC and the reasons for them are detailed in the Supplementary Materials.

Fig. 6. Comparison of reconstructed volume of the PIC in this work to that of negatively-stained human PIC.

(A) Side views of the PIC from this work. Rotated by 60° (left) or −120° (right) relative to front view in Fig. 1A. (B) The reconstruction from negatively-stained human PIC (41) is viewed in the same pol II orientation as in (A). The extra density due to TFIIH (light brown) is only weakly anchored to the remainder of the PIC. The center of mass of TFIIH is displaced by ~90 Å compared to the structure in (A). TFIIE (purple) is dissociated from TBP and TFIIH. Density due to DNA is absent.

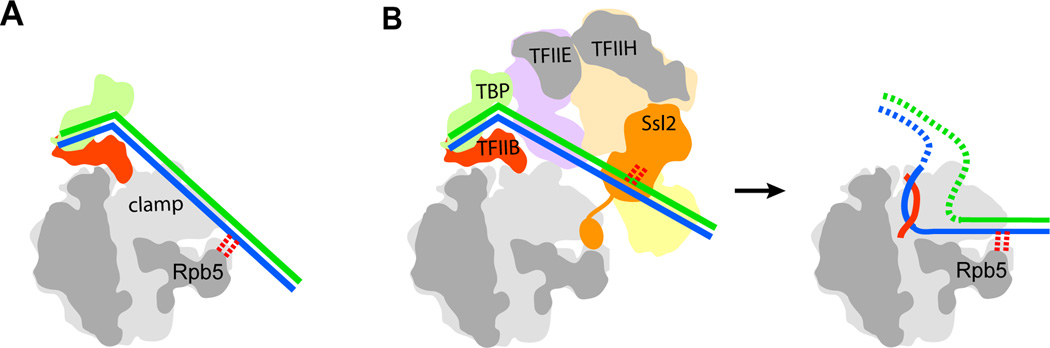

Fig. 7. Comparison of DNA paths within PIC structures.

(A) Cutaway view in schematic representation of cryo-EM structure of PIC lacking TFIIE and TFIIH (41). TFIIF is omitted for clarity. DNA is blue and green. The downstream DNA contacts (red dotted lines) the tip of Rpb5. (B) Left: cutaway view in schematic representation of the complete PIC in this study. TFIIF is omitted for clarity. The C-terminal region of Ssl2 (orange appendage at the bottom of Ssl2) binds residues within the pol II cleft, preventing entry of DNA, which is instead suspended above the cleft, where it interacts with Ssl2 (red dotted lines). Right: cutaway view for the transcribing complex based on the X-ray structure (11), and contact with Rpb5 in the cleft is indicated (red dotted lines). Nascent RNA is red.

The difference in DNA path between the Nogales structures and ours explains a difference between two reports of protein-DNA cross-linking of pol II-GTF-DNA complexes, and suggests a role for the C-terminal domain of Ssl2; a high-frequency cross-link of Rpb5 to DNA downstream of the TATA box was identified for a PIC lacking TFIIH (42, 43), whereas no such cross-link was found for a complete PIC, but instead a cross-link of Ssl2 was observed at the same position (34). The trajectory of the DNA in the Nogales structures, penetrating the pol II cleft at the location of Rpb5, is thus explained by the absence of TFIIE and TFIIH, whereas the location of the DNA in our structure is due to the presence of TFIIH. The position of DNA in the Nogales structures would clash with the location of the C-terminal domain of Ssl2 in the cleft in our structure. We suggest that the site bound by DNA in the Nogales structure is blocked by the C-terminal domain of Ssl2; only after promoter melting and entry of the template strand at the upstream end of the pol II cleft does DNA displace the C-terminal domain of Ssl2 and occupy the downstream end of the cleft (Fig.7B). Region 1.1 of σ70 performs a similar role, binding in the cleft of bacterial RNA polymerase, preventing non-specific DNA interaction, and dissociating upon open complex formation (44).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants GM49885 and AI21144 to R.D.K. and GM063817 to M.L. The EM map has been deposited in the EMDataBank under accession code EMD-2394.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Supplemental Text

Figs. S1 to S14

Tables S1 to S5

Movies S1 to S3

Protein Data Bank file for the PIC model

References (46–65)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Conaway RC, Conaway JW. General initiation factors for RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornberg RD. The molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Aug 7;104:12955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornberg RD. Mediator and the mechanism of transcriptional activation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005 May;30:235. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burley SK, Roeder RG. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Guarente L, Sharp PA. Five intermediate complexes in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1989 Feb 24;56:549. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzder SN, Sung P, Bailly V, Prakash L, Prakash S. RAD25 is a DNA helicase required for DNA repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Nature. 1994 Jun 16;369:578. doi: 10.1038/369578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feaver WJ, Gileadi O, Li Y, Kornberg RD. CTD kinase associated with yeast RNA polymerase II initiation factor b. Cell. 1991 Dec 20;67:1223. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90298-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YJ, Bjorklund S, Li Y, Sayre MH, Kornberg RD. A multiprotein mediator of transcriptional activation and its interaction with the C-terminal repeat domain of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1994 May 20;77:599. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer P, et al. Architecture of RNA polymerase II and implications for the transcription mechanism. Science. 2000 Apr 28;288:640. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer P, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 2001 Jun 8;292:1863. doi: 10.1126/science.1059493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu J, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001 Jun 8;292:1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bushnell DA, Westover KD, Davis RE, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB cocrystal at 4.5 Angstroms. Science. 2004 Feb 13;303:983. doi: 10.1126/science.1090838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostrewa D, et al. RNA polymerase II-TFIIB structure and mechanism of transcription initiation. Nature. 2009 Nov 19;462:323. doi: 10.1038/nature08548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Bushnell DA, Wang D, Calero G, Kornberg RD. Structure of an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex and the transcription initiation mechanism. Science. 2010 Jan 8;327:206. doi: 10.1126/science.1182015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikolov DB, et al. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature. 1995 Sep 14;377:119. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung WH, et al. RNA polymerase II/TFIIF structure and conserved organization of the initiation complex. Mol Cell. 2003 Oct;12:1003. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jawhari A, et al. Structure and oligomeric state of human transcription factor TFIIE. EMBO Rep. 2006 May;7:500. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang WH, Kornberg RD. Electron crystal structure of the transcription factor and DNA repair complex, core TFIIH. Cell. 2000 Sep 1;102:609. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz P, et al. Molecular structure of human TFIIH. Cell. 2000 Sep 1;102:599. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbons BJ, et al. Subunit architecture of general transcription factor TFIIH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 7;109:1949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105266109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami K, et al. Tfb6, a previously unidentified subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH, facilitates dissociation of Ssl2 helicase after transcription initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Mar 27;109:4816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201448109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami K, et al. Formation and Fate of a Complete, 31-Protein, RNA polymerase II Transcription Initiation Complex. J Biol Chem. 2013 Jan 9; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmlund D, Davis R, Elmlund H. Ab initio structure determination from electron microscopic images of single molecules coexisting in different functional states. Structure. 2010 Jul 14;18:777. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elmlund D, Elmlund H. SIMPLE: Software for ab initio reconstruction of heterogeneous single-particles. J Struct Biol. 2012 Aug 10; doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen ZA, et al. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II-TFIIF complex revealed by cross-linking and mass spectrometry. EMBO J. 2010 Feb 17;29:717. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasker K, et al. Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 31;109:1380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120559109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalisman N, Adams CM, Levitt M. Subunit order of eukaryotic TRiC/CCT chaperonin by cross-linking, mass spectrometry, and combinatorial homology modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Feb 21;109:2884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119472109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prather DM, Larschan E, Winston F. Evidence that the elongation factor TFIIS plays a role in transcription initiation at GAL1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Apr;25:2650. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2650-2659.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim B, et al. The transcription elongation factor TFIIS is a component of RNA polymerase II preinitiation complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Oct 9;104:16068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704573104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kastner B, et al. GraFix: sample preparation for single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. Nat Methods. 2008 Jan;5:53. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P. Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS. Mol Cell. 2004 Dec 22;16:955. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996 May 9;381:127. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaiser F, Tan S, Richmond TJ. Novel dimerization fold of RAP30/RAP74 in human TFIIF at 1.7 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000 Oct 6;302:1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller G, Hahn S. A DNA-tethered cleavage probe reveals the path for promoter DNA in the yeast preinitiation complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006 Jul;13:603. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim TK, Ebright RH, Reinberg D. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science. 2000 May 26;288:1418. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holstege FC, Fiedler U, Timmers HT. Three transitions in the RNA polymerase II transcription complex during initiation. EMBO J. 1997 Dec 15;16:7468. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pal M, Ponticelli AS, Luse DS. The role of the transcription bubble and TFIIB in promoter clearance by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2005 Jul 1;19:101. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kainov DE, Vitorino M, Cavarelli J, Poterszman A, Egly JM. Structural basis for group A trichothiodystrophy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008 Sep;15:980. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okuda M, et al. Structural insight into the TFIIE-TFIIH interaction: TFIIE and p53 share the binding region on TFIIH. EMBO J. 2008 Apr 9;27:1161. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okuda M, et al. Structure of the central core domain of TFIIEbeta with a novel double-stranded DNA-binding surface. EMBO J. 2000 Mar 15;19:1346. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He Y, Fang J, Taatjes DJ, Nogales E. Structural visualization of key steps in human transcription initiation. Nature. 2013 Feb 27; doi: 10.1038/nature11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim TK, et al. Trajectory of DNA in the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Nov 11;94:12268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forget D, Langelier MF, Therien C, Trinh V, Coulombe B. Photo-cross-linking of a purified preinitiation complex reveals central roles for the RNA polymerase II mobile clamp and TFIIE in initiation mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Feb;24:1122. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1122-1131.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mekler V, et al. Structural organization of bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme and the RNA polymerase-promoter open complex. Cell. 2002 Mar 8;108:599. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00667-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Complete, 12-subunit RNA polymerase II at 4.1-A resolution: implications for the initiation of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jun 10;100:6969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003 Jun;142:334. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank J, et al. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol. 1996 Jan-Feb;116:190. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999 Dec 1;128:82. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elmlund D, Elmlund H. High-resolution single-particle orientation refinement based on spectrally self-adapting common lines. J Struct Biol. 2009 Jul;167:83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armache KJ, Mitterweger S, Meinhart A, Cramer P. Structures of complete RNA polymerase II and its subcomplex, Rpb4/7. J Biol Chem. 2005 Feb 25;280:7131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leitner A, et al. Expanding the chemical cross-linking toolbox by the use of multiple proteases and enrichment by size exclusion chromatography. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012 Mar;11:M111 014126. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu H, Freitas MA. MassMatrix: a database search program for rapid characterization of proteins and peptides from tandem mass spectrometry data. Proteomics. 2009 Mar;9:1548. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan L, et al. Conserved XPB core structure and motifs for DNA unwinding: implications for pathway selection of transcription or excision repair. Mol Cell. 2006 Apr 7;22:27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fan L, et al. XPD helicase structures and activities: insights into the cancer and aging phenotypes from XPD mutations. Cell. 2008 May 30;133:789. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu H, et al. Structure of the DNA repair helicase XPD. Cell. 2008 May 30;133:801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okamoto T, et al. Analysis of the role of TFIIE in transcriptional regulation through structure-function studies of the TFIIEbeta subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998 Jul 31;273:19866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grunberg S, Warfield L, Hahn S. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex and mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter opening. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012 Aug;19:788. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chakraborty A, et al. Opening and closing of the bacterial RNA polymerase clamp. Science. 2012 Aug 3;337:591. doi: 10.1126/science.1218716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spahr H, Calero G, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Schizosacharomyces pombe RNA polymerase II at 3.6-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jun 9;106:9185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Groft CM, Uljon SN, Wang R, Werner MH. Structural homology between the Rap30 DNA-binding domain and linker histone H5: implications for preinitiation complex assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Aug 4;95:9117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brent MM, Anand R, Marmorstein R. Structural basis for DNA recognition by FoxO1 and its regulation by posttranslational modification. Structure. 2008 Sep 10;16:1407. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science. 2002 May 17;296:1285. doi: 10.1126/science.1069595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Littlefield O, Korkhin Y, Sigler PB. The structural basis for the oriented assembly of a TBP/TFB/promoter complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Nov 23;96:13668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meredith GD, et al. The C-terminal domain revealed in the structure of RNA polymerase II. J Mol Biol. 1996 May 10;258:413. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bushnell DA, Bamdad C, Kornberg RD. A minimal set of RNA polymerase II transcription protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 1996 Aug 16;271:20170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.