Abstract

Inflammation is implicated in the progression of multiple types of cancers including lung, colorectal, breast and hematological malignancies. Cyclooxygenases (Cox) -1 and -2 are important enzymes involved in the regulation of inflammation. Elevated Cox-2 expression is associated with a poor cancer prognosis. Hematological malignancies, which are among the top 10 most predominant cancers in the USA, express high levels of Cox-2. Current therapeutic approaches against hematological malignances are insufficient as many patients develop resistance or relapse. Therefore, targeting Cox-2 holds promise as a therapeutic approach to treat hematological malignancies. NSAIDs and Cox-2 selective inhibitors are anti-inflammatory drugs that decrease prostaglandin and thromboxane production while promoting the synthesis of specialized proresolving mediators. Here, we review the evidence regarding the applicability of NSAIDs, such as aspirin, as well as Cox-2 specific inhibitors, to treat hematological malignancies. Furthermore, we discuss how FDA-approved Cox inhibitors can be used as anti-cancer drugs alone or in combination with existing chemotherapeutic treatments.

Inflammation and cancer

Inflammation is a critical step during the immune response, which can be triggered by foreign pathogens, injury or trauma. Inflammation is characterized by the four cardinal signs, rubor, dolor, calor and tumor. Regulating the beginning of inflammation, as well as its resolution, is a fundamental process required to prevent disease while maintaining homeostasis. A deficient inflammatory response will hinder the activation of the immune system, in turn aiding pathogen infiltration and preventing tissue healing. Alternatively, uncontrolled or chronic inflammation can lead to disease such as autoimmune disorders and cancer (1).

Inflammation and cancer share pathological characteristics that include increased blood flow, cellular recruitment and tissue remodeling (2,3). Inflammation is implicated in the progression of multiple types of cancers including lung, colorectal, breast, head, neck, and hematological malignancies (4–11). Understanding and more importantly, regulating inflammation is a vital component for the development of novel and efficient cancer therapies.

Cyclooxygenases (Cox) are important enzymes involved in the regulation of inflammation. Cox-1 and Cox-2 isoforms are associated with the production of proinflammatory prostanoids including prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxanes (TXs) (12). Cox-1 is constitutively expressed and regulates basal prostanoid levels. Conversely, the inducible isoform, Cox-2, upregulates prostanoid production during inflammatory conditions (12). Because of its proinflammatory properties, Cox-2 is considered an oncogene. Increased Cox-2 expression is associated with a poor cancer prognosis (5–8).

Following cleavage of arachidonic acid from the cell membrane, Cox-2 regulates the production of PGH2, a major intermediate from which multiple PGs and TXs are biosynthesized. PGE2, a well-studied prostaglandin produced from PGH2, is a potent proinflammatory lipid molecule capable of increasing blood flow and cell permeability into the tissue (13). Increased Cox-2 and PGE2 production are associated with carcinoma progression and metastasis in hematological malignancies, as well as lung, colon and gastric carcinomas among others (9–11,14,15). Given the link between Cox-2, its bioactive lipid-products and cancer, both selective and non-selective Cox inhibitors are being investigated in the clinic as potential treatments for cancer.

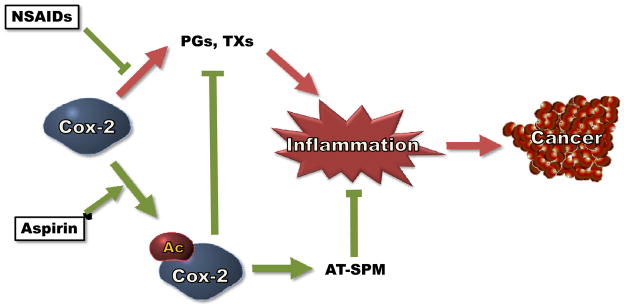

In addition to the proinflammatory PGs and TXs, arachidonic acid is metabolized via an alternative enzymatic pathway mediated by acetylated Cox-2 and lipoxygenases (LOXs). LOXs are an enzymatic family responsible for the production of leukotrienes (LTs) and lipoxins (16,17). Lipoxins are a relatively new set of molecules that belong to a class of lipid mediators called specialized proresolving mediators (SPM) (18). SPM are thought to have anti-cancer properties because, unlike their biosynthetic prostanoid counter parts, SPM help arrest and resolve inflammation (16,19). In this review, we will discuss the potential of Cox-2 and its bioactive lipid derived products as therapeutic targets to treat hematological malignancies. Figure 1 outlines the potential mechanism by which Cox-2 inhibitors decrease inflammation and decrease cancer risk.

Figure 1.

Cox-2 inhibitors can decrease the risk of cancer. Both non-aspirin NSAIDs and aspirin inhibit the ability of Cox-2 to produce proinflammatory prostaglandins (PGs) and thromboxanes (TXs). In addition, aspirin-mediated acetylation of Cox-2 (Ac-Cox-2) triggers the production of aspirin-triggered specialized proresolving mediators (AT-SPM), which have anti-cancer properties.

Inhibiting Cox-2 in hematological malignancies

The most recent survey by the CDC and the National Cancer Institute, categorize hematological malignancies among the top 10 most predominant cancers in the US. In 2008, 54,576 people died from a hematologic cancers and 124,556 more were diagnosed with a form of cancer in their blood, bone marrow or lymph node (20,21). This is a great health concern at a national and global scale. Interestingly, hematological malignancies generally express high levels of Cox-2 (22–26). Elevated Cox-2 expression is correlated to poor prognosis and decreased survival in many types of cancers (22–25). Cox-2 selective inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have important anti-inflammatory properties. NSAIDs include both Cox-2 selective inhibitors (i.e. meloxicam, celecoxib) and non-selective inhibitors (i.e. aspirin, indomethacin, ibuprofen). Both Cox-2 selective inhibitors and NSAIDs, possess pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative properties and thus have anti-carcinogenic properties.

Studies performed in our laboratory demonstrated that healthy human B cells do not express Cox-2 under resting conditions. However, B cells increase Cox-2 expression upon mitogen activation (27,28). Furthermore, we and others have shown that hematological malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells express high levels of Cox-2, which promotes cell survival (22,29). Foremost, Cox-2 inhibitors, such as indomethacin, celecoxib (Celebrex), SC-58125 and OSU03012 inhibit the Cox-2-mediated pro-survival mechanisms in multiple malignancies, including hematological cancers (22,29–31). Chandramohan and colleagues demonstrated that Cox-2 overexpression provides anti-apoptotic properties to chronic myeloid leukemia cells (CML). By overexpressing Cox-2 in K562 cells, Chandramohan et al. found that the CML cells are less susceptible to gallic acid-induced apoptosis, an effect attributed in part to increased expression of Bcl-2 and decreased of cytochrome c release (32). Other NSAIDs, such as aspirin, are reported to have similar pro-apoptotic effects on CLL cells. Iglesias-Serret et al. have shown that aspirin-induced apoptosis in primary CLL and leukemia Jurkat T cells is regulated by the Bcl-2 family members Mcl-1 and Noxa (33).

Besides their pro-apoptotic properties, Cox-2 inhibitors also hold promise as cancer therapeutics as they decrease cell proliferation. Sobolewski et al. have shown that Cox-2 specific inhibitors promote a cytostatic state in CML and acute myeloid lymphoma (AML) cells. Nimesulide, NS-398 and celecoxib, decrease proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase by downregulating the expression of c-Myc and p27 (34). These findings are in support of previous reports in which Cox-2 inhibitors such as, indomethacin, celecoxib and Dup-697, decreased proliferation, promote cell cycle arrest and induce apoptosis in both primary CML cells, as well as CML cell lines (35–38). Cox-2 specific inhibitors such as celecoxib and NS-398 also decrease malignant cell growth and proliferation in models of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and multiple myelomas, both in vitro and in vivo (39,40). Naturally-occurring small molecules such as quercetin and decursin, which are not NSAIDs, have also been shown to target and inhibit Cox-2 function (41–43). Ahn and colleagues showed that decursin, similarly to the Cox-2 inhibitors NS398 and celecoxib, reduced Cox-2 expression in the CML cell line KBM-5. The downregulation of Cox-2 in CML leads to cell cycle arrest and increases apoptosis (43), an effect that is consistent with decursin as an anti-carcinogenic agent. Therefore, inhibiting Cox-2 decreases malignant cell proliferation, an important component during cancer treatment.

In addition to their pro-apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects, Cox-2 inhibitors also possess anti-angiogenic properties. An inflammatory tumor microenvironment promotes angiogenesis and growth, thus leading to malignancy progression. Angiogenesis is dependent on multiple variables including key cell growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). Cox-2 promotes angiogenesis by increasing VEGF and FGF production (9,44). In a melanoma murine model, Valcarcel et al. have shown that tumor growth and metastasis are dependent on VEGF signaling. Most importantly, the Cox-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, blocked tumor metastasis in vivo (45). These observations complement previous clinical studies in which celecoxib in combination with chemotherapy, decreased the circulating serum levels of VEGF (46). A report by Chien et al. shows that in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), VEGF-C increases Cox-2 expression via JNK signaling. Consequently, higher Cox-2 activity increases production of proinflammatory prostaglandins, which in turn promote angiogenesis (47). These findings are intriguing, as they may suggest a positive feedback mechanism between Cox-2 and VEGF production. Further analyses are required to better understand the role of Cox-2 during angiogenesis. However, the findings discussed here, firmly support the translational power of Cox-2 inhibitors as potential cancer therapeutics.

Using Cox-2 inhibitors in the clinic

Given the pro-oncogenic properties of Cox-2, there is much interest in the development of therapies targeting Cox-2 during cancer progression (10,24). NSAIDs can lower the risk for colon, breast, esophagus and stomach cancer (48). Furthermore, multiple population-study reports support NSAIDs as potential agents to treat hematological malignancies. In a case-control study, Pogada and colleagues found that use (≥4 weeks for 2–10 years) of NSAIDs (most commonly used being ibuprofen, naproxen and piroxicam) decreased the risk of AML by 50% (49). More recently, a population study performed by Weiss et al. pooled 169 acute leukemia patients and compared them to 676 controls. Based on a comprehensive epidemiological questionnaire, Weiss reported that the regular use of aspirin (>3 times/week) over a 12-year period provided a protective effect against hematological malignancies. More specifically, aspirin intake strongly decreased the risk for developing acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and moderately decreased the risk for AML (50). An additional population-based case-control study by Ross and colleagues, analyzed the effects of NSAIDs in 670 newly diagnosed AML and CML patients. Regular-dose aspirin intake (≥1 × 325 mg table/week for ≥ 1 year) was found to decrease the risk of myeloid leukemia by 41% in women but not in men (51).

Interestingly, not all NSAIDs have protective effects against cancer. Some NSAIDs have been linked to increased risk for hematological malignancies. In a study by Vinogradova et al. it was found that use of Cox-2 inhibitors (mostly rofecoxib, celecoxib and meloxicam) increased the risk for hematological malignancies by 18% if taken short-term (≥ 1 prescription for 3–12 months) or up to 47% on long-term users (≥1 prescription for ≥ 2 years) (52). This is in contrast to previous studies and although Vinogradova’s study used a large cohort that included 88,125 cancer patients, hematological malignancies were not the only focus of their study, thus their data is derived from a limited number of subjects with hematological cancers. The group of Walter and colleagues performed an additional population study to measure the effects of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs specifically on hematological malignancies. Using 64,839 subjects as their sample population, the team found that high use (≥ 4 days/week for ≥ 4 years) of acetaminophen increased the risk of hematologic malignancies, myeloid neoplasm, mature B-cell neoplasm, but not chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (53). A different study by Weiss et al. also found that even a single use of acetaminophen increased the risk of ALL and AML and continued usage by 53% (50). In addition, acetaminophen also increased the risk for AML and CML in women independently of the dose or duration of acetaminophen intake (51). Two other population-based case-control studies by Chang and colleagues reported on the contrasting outcomes of different NSAIDs, particularly acetaminophen and aspirin (54,55). The authors reported that acetaminophen increased the risk of Hodgkin’s lymphoma by 72%. On the other hand, taking aspirin regularly (≥ 2 times of 325 mg tablets/week) reduced lymphoma incidence by 40% (54), and by 30% in subjects taking low-dose aspirin (> 2 times s of 75, 100, or 150 mg tablets/month) (55). Even though these population-based studies show promising correlations between NSAID use and decreased hematological malignancies, it is important to acknowledge that many are limited by the availability of detailed patient information, size of the population studied and ability to perform long-term patient progress.

It is safe to say that the effects of the NSAIDs on hematological malignancies are far from uniform. Aspirin’s protective properties are strongly contrasted by acetaminophen’s enhanced risk for malignancies, while ibuprofen, for example, has been shown to have no effect on the incidence of hematological malignancies (51,53). Considering the specific cancer-responses seen to different kinds of NSAIDs, detailed examination of the molecular mechanisms responsible for their effects will allow for the development of improved therapeutic treatments.

Alternative use of Cox-2 inhibitors

Current approaches to treat hematological malignancies include radiotherapy and chemotherapeutic agents (56–58). Nevertheless, traditional therapies are not always sufficient. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and imitinib, are two examples of commonly used treatments against AML and CML, to which patients develop resistance and suffer relapse (59–61). Cox-2 inhibitors are viable therapeutic alternatives to improve cancer treatment efficacy. Already, Cox-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, have shown protective effects against the development of colorectal cancer (62,63). Other Cox-2 specific inhibitors, including celecoxib and rofecoxib, have also been reported to minimize the risk for lung cancer (64). Nevertheless, the use of selective Cox-2 inhibitors, particularly at high concentrations, can lead to serious cardiovascular complications (65).

A promising approach involves the inclusion of NSAIDs to already existing chemotherapeutic treatments. Puhlmann and colleagues have shown that using meloxicam, a Cox-2 specific inhibitor, along with the chemotherapeutic agent, doxorubicin, decreases malignant cell growth and proliferation of hematological malignancies (66). In their study, Puhlmann et al showed a decreased in proliferation by 30% in AML, and 78% in HL-60 cells, which were treated with meloxicam and doxorubicin. Interestingly, expression of the multidrug transporter MDR1, which is responsible for multidrug resistance in AML patients, was downregulated by meloxicam treatment (66). The clinical chemotherapeutics properties of meloxicam have also been reported in other types of cancers. A study by Suzuki et al. showed that non-small lung carcinoma patients given a combined chemotherapeutic treatment consisting of paclitaxel weekly, for 3 weeks with carboplatin on day 1, and a daily dose (10 mg/day) of meloxicam have a 43% improved treatment response (67). Meloxicam (10 mg/day for a median period of 20 months) has also been used to effectively decreased the size of extra-abdominal desmoid tumors (68).

Importantly, some Cox-2 inhibitors have the capacity to target malignant cells, while not adversely affecting normal cells. Secchiero et al. have shown that the Cox-2 inhibitor, NS-398 and DuP697, promote apoptosis in B-CLL cells, but not in healthy cells. Furthermore, the chemotherapeutic agent chlorambucil in combination with NS-398 increases B-CLL cell death (29). Jamshidi et al. also reported that using 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, the active form of vitamin D, along with indomethacin and aspirin, enhances human myeloid leukemia cell differentiation while decreasing cell proliferation. These synergistic effects are seen in primary AML as well as HL-60, THP-1 and U937 cell lines (69). Therefore the use of Cox-2 inhibitors in combination with established cancer therapies holds great promise as a novel alternative strategy to treat cancer.

Using aspirin to treat cancer

Aspirin is one of the most promising NSAIDs as a potential anti-cancer drug. Aspirin is a traditional and time-honored anti-inflammatory drug to reduce pain, fever, and even the risk for cardiovascular disorders. Aspirin is an irreversible non-specific Cox inhibitor that acetylates serine-530 within the Cox-2 active site, thus transforming Cox-2 enzymatic properties (70). A plethora of evidence exists demonstrating that aspirin consumption has beneficial effects as a treatment for many types of cancers, including hematological malignancies (71,72).

Early reports by Kasum and colleagues found that aspirin use (≥2/week) in a cohort of 28,224 postmenopausal women, decreased the risk of developing leukemia (including AML, CLL and CML) by 65% (73). Some of the most striking and latest reports have shown that regular aspirin intake has a strong protective influence against colorectal and other solid cancers. Rothwell and colleagues reported that high-dose (≥500 mg/day) aspirin intake lowers the risk of colorectal cancer by 24% and improves patient survival by 35%. Interestingly, long-term (≥ 5years) aspirin use reduces the risk of proximal colon cancer by 70% (74). Considering the previously discussed role of Cox-2 in angiogenesis, aspirin’s long-term protective effects are attributed in part to decreased tumor metastasis (75). In an later population-study consisting of 17,285 patients from the United Kingdom, Rothwell et al. observed that long-term (≥ 5years) daily aspirin consumption (≥ 75 mg/day) decreases the risk of metastasis of colorectal and adenocarcinomas as well as the incidence of cancer-associated death (75). These large population-studies provide another set of strong evidence highlighting the anti-carcinogenic properties of aspirin on multiple types of malignancies. Better understanding the properties and mechanism(s) responsible for aspirin’s beneficial effects are necessary in order to develop better treatments against cancers, such as hematological malignancies.

While it is clear that aspirin therapy is associated with decreased risk for certain cancers and can inhibit metastasis, the underpinning mechanisms responsible for its multiple actions in vivo are not elucidated. Hawley et al. have shown that salicylate, a breakdown product of aspirin, activates AMP kinase (76,77). This is done by way of salicylate inhibiting threonine-172 dephosphorylation, which in turn increases AMP kinase ability to produce ATP (77). Alternatively, diabetes drugs such as the thiazolidinediones (TZDs), a class of PPARγ ligands, can stimulate AMP kinase function and decrease Cox-2 expression (78,79). TZDs and other PPARγ ligands, have anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic properties on hematological malignancies including multiple myeloma, Burtkit’s lymphoma and myeloid leukemia cells (80–82). Whether aspirin and AMP kinase signaling are involved in the regulation of hematological malignancies has not yet been explored.

Interestingly, not all studies regarding aspirin have been promising. A study done by Cook et al. surveyed 39,876 women who were given aspirin (100 mg/every other day) or placebo. Cook’s analysis showed a decreased risk for lung cancer (22%), but not for colorectal cancer, breast cancer or cancer of any other site (83). However, the dose and frequency (100 mg/every other day) of aspirin used in their studies is different from many of the previous studies. This raises important issues regarding dosing and timing of aspirin use when treating different types of cancer.

Furthermore, aspirin’s beneficial properties come with unwanted side effects, the most common being gastrointestinal complications (84). Most of aspirin’s adverse effects are associated with the inhibition of Cox-1, which disrupts prostanoid homeostasis in the gut. Pepper et al. showed that the aspirin analogs 2-hydroxy benzoate zinc (2HBZ) and 4-hydroxy benzoate zinc (4HBZ) can induce apoptosis in primary CLL cells by activating the caspase-3 signaling pathway. Of particular interest, 2HBZ and 4HBZ decrease Cox-2 expression, but do not affect Cox-1 levels. (85). Novel aspirin analogues could be used to selectively acetylate and inhibit Cox-2, thus minimizing Cox-1-related adverse effects. However, using aspirin as a preventive therapy against malignancies requires long-term use, thus it is important to carefully examine the risk to benefit profile for each individual. On going long-term studies, such as the ASPREE study (NCT01038583), will provide further information regarding the safety of long-term low-dose aspirin treatments (86).

Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxins: Novel therapeutic agents

The beneficial effects of aspirin, by which it decreases inflammation and prevents cancer, go beyond the inhibition of PGs and TXs production. Serhan et al. proposed that the aspirin-mediated Cox-2 acetylation is responsible for the production of the novel SPM namely, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and aspirin-triggered resolvins (87–89). Specialized proresolving mediators play a crucial role in the regulation of inflammation, particularly during the resolution phase. SPM resolve inflammation, restore tissue homeostasis and prevent chronic inflammation (19). Aspirin inhibits proinflammatory mediator production and in parallel induces the synthesis of pro-resolution SPM molecules. This unique mechanism may explain some of aspirin’s beneficial effects during cancer treatment that are not observed with other NSAIDs.

Both arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are precursors to different families of bioactive lipid mediators including SPM. Arachidonic acid and DHA, are omega-6 and omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) respectively (19). PUFA have been shown to have protective effects on breast cancer, neuroblastoma and renal cancer development (90–94). In breast cancer for example, PUFA increased the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin and docetaxel on malignant cells while protectin healthy cells (90,91). In addition, Comba et al. showed in a mouse model that an omega-6 rich diet, which increases the levels of arachidonic acid in the cell membrane, decreased mammary gland tumor metastasis and volume, and consequently increased the animal’s survival (95). Interesting observations tying together SPM and cancer have recently been made by Jin and colleagues, who showed that aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4, has anti-angiogenic properties, as it significantly reduces VEGF-A-induced vascular angiogenesis in vivo (96). In addition, Chen et al. have recently described similar observations, in which lipoxin A4 and its analog BML-111, decrease the production of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α and VEGF in hepatocarcinoma cells. Likewise, in a murine model of liver cancer, lipoxin A4 and BML-111 have been shown to regulate and inhibit hepatocarcinoma tumor growth (97,98). In vitro .lipoxin A4 also decreases AML cell migration, while promoting macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (99).

SPM are a relatively newly discovered family of bioactive lipids. Investigating the alternative biosynthetic pathways of Cox-2 as a way to decrease PGs and TXs production and increase the levels of beneficial SPM is a promising new area of study. Targeting SPM as well as SPM-promoting Cox-2 inhibitors could lead to development of highly effective and safer therapies for hematological malignancies and other cancers.

Concluding remarks

Current chemotherapeutic therapies against hematological malignances are insufficient. Many patients develop resistance to treatment or suffer devastating relapse. Therefore, the development of new approaches to treat cancer is imperative. Given that Cox-2 plays a crucial role in cancer development, pursuing the use of Cox-2 inhibitors as preventive therapeutic agents holds great promise. The use of FDA approved Cox inhibitors could provide a distinct advantage, as it would expedite clinical studies and minimize the risk of unknown drug-related side effects associated with newly developed molecules.

There is burgeoning evidence regarding the applicability of NSAIDs, such as aspirin and other Cox-2 specific inhibitors, to treat hematological malignancies. Combining current therapeutic treatments, including radiation and chemotherapy, with Cox-2 inhibitors is a viable approach, which so far has provided promising results. Nonetheless, using Cox inhibitors to treat malignancies can still present unwanted health risks, and a better understanding of the mechanisms by which Cox inhibitors regulate inflammation and minimize the risk of cancer is essential in order to improve current treatments. Lastly, SPM have great potential to be used as anti-cancer agents. Novel therapeutic drugs, should aim to not only the inhibit Cox-2-mediated PGs and TXs production, but also to increase the production of SPM.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants ES01247, T32 DE007202 and AI103690

References

- 1.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):428–35. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(7):1073–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zweifel BS, Davis TW, Ornberg RL, Masferrer JL. Direct evidence for a role of cyclooxygenase 2-derived prostaglandin E2 in human head and neck xenograft tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6706–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denkert C, Winzer KJ, Muller BM, Weichert W, Pest S, Kobel M, et al. Elevated expression of cyclooxygenase-2 is a negative prognostic factor for disease free survival and overall survival in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97(12):2978–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto A, Yokoyama Y, Umemoto M, Futagami M, Sakamoto T, Bing X, et al. Clinical implication of expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and peroxisome proliferator activated-receptor gamma in epithelial ovarian tumours. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(4):633–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohadwala M, Batra RK, Luo J, Lin Y, Krysan K, Pold M, et al. Autocrine/paracrine prostaglandin E2 production by non-small cell lung cancer cells regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 and CD44 in cyclooxygenase-2-dependent invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(52):50828–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210707200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles FJ, Kantarjian HM, Bekele BN, Cortes JE, Faderl S, Thomas DA, et al. Bone marrow cyclooxygenase-2 levels are elevated in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia and are associated with reduced survival. Br J Haematol. 2002;119(1):38–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo IL, Pavelka M, Baatar D, Tarnawski AS. Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8(3):289–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard MP, Bancos S, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in hematological malignancies: rationale and promise. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(21):2051–60. doi: 10.2174/138161208785294654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young LE, Dixon DA. Posttranscriptional Regulation of Cyclooxygenase 2 Expression in Colorectal Cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2010;6(2):60–7. doi: 10.1007/s11888-010-0044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FitzGerald GA. COX-2 and beyond: Approaches to prostaglandin inhibition in human disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(11):879–90. doi: 10.1038/nrd1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 2012;188(1):21–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosomi Y, Yokose T, Hirose Y, Nakajima R, Nagai K, Nishiwaki Y, et al. Increased cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression occurs frequently in precursor lesions of human adenocarcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2000;30(2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagatsuka I, Yamada N, Shimizu S, Ohira M, Nishino H, Seki S, et al. Inhibitory effect of a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor on liver metastasis of colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;100(5):515–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serhan CN, Petasis NA. Resolvins and protectins in inflammation resolution. Chem Rev. 2011;111(10):5922–43. doi: 10.1021/cr100396c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haeggstrom JZ, Funk CD. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem Rev. 2011;111(10):5866–98. doi: 10.1021/cr200246d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):349–61. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serhan CN, Clish CB, Brannon J, Colgan SP, Chiang N, Gronert K. Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med. 2000;192(8):1197–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) 2011 [cited 2012 April]; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/

- 21.Group. USCSW. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2008 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. [cited 2012 May]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/uscs.

- 22.Ryan EP, Pollock SJ, Kaur K, Felgar RE, Bernstein SH, Chiorazzi N, et al. Constitutive and activation-inducible cyclooxygenase-2 expression enhances survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Clin Immunol. 2006;120(1):76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohsawa M, Fukushima H, Ikura Y, Inoue T, Shirai N, Sugama Y, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in Hodgkin’s lymphoma: its role in cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(9):1863–71. doi: 10.1080/10428190600685442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ. Cyclooxygenase 2: a molecular target for cancer prevention and treatment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24(2):96–102. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladetto M, Vallet S, Trojan A, Dell’Aquila M, Monitillo L, Rosato R, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is frequently expressed in multiple myeloma and is an independent predictor of poor outcome. Blood. 2005;105(12):4784–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trojan A, Tinguely M, Vallet S, Seifert B, Jenni B, Zippelius A, et al. Clinical significance of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in multiple myeloma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(25–26):400–3. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernard MP, Phipps RP. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induce cyclooxygenase-2 in human B lymphocytes: implications for adjuvant activity and antibody production. Clin Immunol. 2007;125(2):138–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan EP, Pollock SJ, Murant TI, Bernstein SH, Felgar RE, Phipps RP. Activated human B lymphocytes express cyclooxygenase-2 and cyclooxygenase inhibitors attenuate antibody production. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2619–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Secchiero P, Barbarotto E, Gonelli A, Tiribelli M, Zerbinati C, Celeghini C, et al. Potential pathogenetic implications of cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in B chronic lymphoid leukemia cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(6):1599–607. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson AJ, Smith LL, Zhu J, Heerema NA, Jefferson S, Mone A, et al. A novel celecoxib derivative, OSU03012, induces cytotoxicity in primary CLL cells and transformed B-cell lymphoma cell line via a caspase- and Bcl-2-independent mechanism. Blood. 2005;105(6):2504–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu AL, Ching TT, Wang DS, Song X, Rangnekar VM, Chen CS. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib induces apoptosis by blocking Akt activation in human prostate cancer cells independently of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(15):11397–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandramohan Reddy T, Bharat Reddy D, Aparna A, Arunasree KM, Gupta G, Achari C, et al. Anti-leukemic effects of gallic acid on human leukemia K562 cells: downregulation of COX-2, inhibition of BCR/ABL kinase and NF-kappaB inactivation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26(3):396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iglesias-Serret D, Pique M, Barragan M, Cosialls AM, Santidrian AF, Gonzalez-Girones DM, et al. Aspirin induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells independently of NF-kappaB and MAPKs through alteration of the Mcl-1/Noxa balance. Apoptosis. 2010;15(2):219–29. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobolewski C, Cerella C, Dicato M, Diederich M. Cox-2 inhibitors induce early c-Myc downregulation and lead to expression of differentiation markers in leukemia cells. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(17):2978–93. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.17.16460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Tu C, Zhang G, Zhou G, Zheng W. Indomethacin induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk Res. 2000;24(5):385–92. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(99)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subhashini J, Mahipal SV, Reddanna P. Anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of celecoxib on human chronic myeloid leukemia in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2005;224(1):31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang GS, Liu DS, Dai CW, Li RJ. Antitumor effects of celecoxib on K562 leukemia cells are mediated by cell-cycle arrest, caspase-3 activation, and downregulation of Cox-2 expression and are synergistic with hydroxyurea or imatinib. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(4):242–55. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng HL, Zhang GS, Liu JH, Gong FJ, Li RJ. Dup-697, a specific COX-2 inhibitor, suppresses growth and induces apoptosis on K562 leukemia cells by cell-cycle arrest and caspase-8 activation. Ann Hematol. 2008;87(2):121–9. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Abe Y, Matsushima T, Nishimura J, Nawata H, Muta K. Selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor NS-398 induces apoptosis in myeloma cells via a Bcl-2 independent pathway. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(3):425–33. doi: 10.1080/10428190400015691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kardosh A, Wang W, Uddin J, Petasis NA, Hofman FM, Chen TC, et al. Dimethyl-celecoxib (DMC), a derivative of celecoxib that lacks cyclooxygenase-2-inhibitory function, potently mimics the anti-tumor effects of celecoxib on Burkitt’s lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(5):571–82. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.5.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerella C, Sobolewski C, Dicato M, Diederich M. Targeting COX-2 expression by natural compounds: a promising alternative strategy to synthetic COX-2 inhibitors for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(12):1801–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao X, Shi D, Liu L, Wang J, Xie X, Kang T, et al. Quercetin suppresses cyclooxygenase-2 expression and angiogenesis through inactivation of P300 signaling. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn Q, Jeong SJ, Lee HJ, Kwon HY, Han I, Kim HS, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2-dependent survivin mediates decursin-induced apoptosis in human KBM-5 myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;298(2):212–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ribatti D, Vacca A, Rusnati M, Presta M. The discovery of basic fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor-2 and its role in haematological malignancies. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18(3–4):327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valcarcel M, Mendoza L, Hernandez JJ, Carrascal T, Salado C, Crende O, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates melanoma cell adhesion and growth in the bone marrow microenvironment via tumor cyclooxygenase-2. J Transl Med. 2011;9:142. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buckstein R, Kerbel RS, Shaked Y, Nayar R, Foden C, Turner R, et al. High-Dose celecoxib and metronomic “low-dose” cyclophosphamide is an effective and safe therapy in patients with relapsed and refractory aggressive histology non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(17):5190–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chien MH, Ku CC, Johansson G, Chen MW, Hsiao M, Su JL, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C) promotes angiogenesis by induction of COX-2 in leukemic cells via the VEGF-R3/JNK/AP-1 pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(12):2005–13. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moran EM. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer risks. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2002;21(2):193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pogoda JM, Katz J, McKean-Cowdin R, Nichols PW, Ross RK, Preston-Martin S. Prescription drug use and risk of acute myeloid leukemia by French-American-British subtype: results from a Los Angeles County case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(4):634–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss JR, Baker JA, Baer MR, Menezes RJ, Nowell S, Moysich KB. Opposing effects of aspirin and acetaminophen use on risk of adult acute leukemia. Leuk Res. 2006;30(2):164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross JA, Blair CK, Cerhan JR, Soler JT, Hirsch BA, Roesler MA, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and acetaminophen use and risk of adult myeloid leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1741–50. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Exposure to cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and risk of cancer: nested case-control studies. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(3):452–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walter RB, Milano F, Brasky TM, White E. Long-term use of acetaminophen, aspirin, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of hematologic malignancies: results from the prospective Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2424–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang ET, Zheng T, Weir EG, Borowitz M, Mann RB, Spiegelman D, et al. Aspirin and the risk of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a population-based case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(4):305–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang ET, Cronin-Fenton DP, Friis S, Hjalgrim H, Sorensen HT, Pedersen L. Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in relation to Hodgkin lymphoma risk in northern Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(1):59–64. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kay NE. Purine analogue-based chemotherapy regimens for patients with previously untreated B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2006;43(2 Suppl 2):S50–4. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, Kantarjian H, Wen S, Do KA, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(4):975–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gospodarowicz M. Radiotherapy in non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 4):iv47–50. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linenberger ML. CD33-directed therapy with gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute myeloid leukemia: progress in understanding cytotoxicity and potential mechanisms of drug resistance. Leukemia. 2005;19(2):176–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pagano L, Fianchi L, Caira M, Rutella S, Leone G. The role of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia patients. Oncogene. 2007;26(25):3679–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hochhaus A, Kreil S, Corbin AS, La Rosee P, Muller MC, Lahaye T, et al. Molecular and chromosomal mechanisms of resistance to imatinib (STI571) therapy. Leukemia. 2002;16(11):2190–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan AT, Zauber AG, Hsu M, Breazna A, Hunter DJ, Rosenstein RB, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C9 variants influence response to celecoxib for prevention of colorectal adenoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(7):2127–36. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, Racz I, Dite P, Hajer J, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):885–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris RE, Beebe-Donk J, Alshafie GA. Reduced risk of human lung cancer by selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) blockade: results of a case control study. Int J Biol Sci. 2007;3(5):328–34. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topol EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA. 2001;286(8):954–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puhlmann U, Ziemann C, Ruedell G, Vorwerk H, Schaefer D, Langebrake C, et al. Impact of the cyclooxygenase system on doxorubicin-induced functional multidrug resistance 1 overexpression and doxorubicin sensitivity in acute myeloid leukemic HL-60 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(1):346–54. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suzuki R, Yamamoto M, Saka H, Taniguchi H, Shindoh J, Tanikawa Y, et al. A phase II study of carboplatin and paclitacel with meloxicam. Lung Cancer. 2009;63(1):72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Shido Y, Wasa J, Ishiguro N, Yamada Y. Successful treatment with meloxicam, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, of patients with extra-abdominal desmoid tumors: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):e107–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jamshidi F, Zhang J, Harrison JS, Wang X, Studzinski GP. Induction of differentiation of human leukemia cells by combinations of COX inhibitors and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 involves Raf1 but not Erk 1/2 signaling. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(7):917–24. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loll PJ, Picot D, Garavito RM. The structural basis of aspirin activity inferred from the crystal structure of inactivated prostaglandin H2 synthase. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2(8):637–43. doi: 10.1038/nsb0895-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Elwood PC, Gallagher AM, Duthie GG, Mur LA, Morgan G. Aspirin, salicylates, and cancer. Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1301–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cuzick J, Otto F, Baron JA, Brown PH, Burn J, Greenwald P, et al. Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: an international consensus statement. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):501–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kasum CM, Blair CK, Folsom AR, Ross JA. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of adult leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(6):534–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, Norrving B, Algra A, Warlow CP, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9754):1741–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, Belch JF, Meade TW, Mehta Z. Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: a study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1591–601. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Higgs GA, Salmon JA, Henderson B, Vane JR. Pharmacokinetics of aspirin and salicylate in relation to inhibition of arachidonate cyclooxygenase and antiinflammatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84(5):1417–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, Walker KJ, et al. The Ancient Drug Salicylate Directly Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1215327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruderman N, Prentki M. AMP kinase and malonyl-CoA: targets for therapy of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(4):340–51. doi: 10.1038/nrd1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu JJ, Liu PQ, Lin DJ, Xiao RZ, Huang M, Li XD, et al. Downregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression and activation of caspase-3 are involved in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists induced apoptosis in human monocyte leukemia cells in vitro. Ann Hematol. 2007;86(3):173–83. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia-Bates TM, Bernstein SH, Phipps RP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma overexpression suppresses growth and induces apoptosis in human multiple myeloma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(20):6414–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garcia-Bates TM, Peslak SA, Baglole CJ, Maggirwar SB, Bernstein SH, Phipps RP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma overexpression and knockdown: impact on human B cell lymphoma proliferation and survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(7):1071–83. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0625-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirase N, Yanase T, Mu Y, Muta K, Umemura T, Takayanagi R, et al. Thiazolidinedione induces apoptosis and monocytic differentiation in the promyelocytic leukemia cell line HL60. Oncology. 1999;57 (Suppl 2):17–26. doi: 10.1159/000055271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cook NR, Lee IM, Gaziano JM, Gordon D, Ridker PM, Manson JE, et al. Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thiagarajan P, Jankowski JA. Aspirin and NSAIDs; benefits and harms for the gut. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(2):197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pepper C, Mahdi JG, Buggins AG, Hewamana S, Walsby E, Mahdi E, et al. Two novel aspirin analogues show selective cytotoxicity in primary chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells that is associated with dual inhibition of Rel A and COX-2. Cell Prolif. 2011;44(4):380–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Health USNIo. Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) U.S. National Institutes of Health; [cited 2012 June 11th]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01038583?term=aspree&rank=1. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chiang N, Serhan CN. Aspirin triggers formation of anti-inflammatory mediators: New mechanism for an old drug. Discov Med. 2004;4(24):470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Serhan CN. Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxins are the first lipid mediators of endogenous anti-inflammation and resolution. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73(3–4):141–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, et al. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med. 2002;196(8):1025–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Menendez JA, Ropero S, Lupu R, Colomer R. Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid gamma-linolenic acid (18:3n-6) enhances docetaxel (Taxotere) cytotoxicity in human breast carcinoma cells: Relationship to lipid peroxidation and HER-2/neu expression. Oncol Rep. 2004;11(6):1241–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maheo K, Vibet S, Steghens JP, Dartigeas C, Lehman M, Bougnoux P, et al. Differential sensitization of cancer cells to doxorubicin by DHA: a role for lipoperoxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39(6):742–51. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Das UN. Gamma-linolenic acid, arachidonic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid as potential anticancer drugs. Nutrition. 1990;6(6):429–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gleissman H, Segerstrom L, Hamberg M, Ponthan F, Lindskog M, Johnsen JI, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation delays the progression of neuroblastoma in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1703–11. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wolk A, Larsson SC, Johansson JE, Ekman P. Long-term fatty fish consumption and renal cell carcinoma incidence in women. JAMA. 2006;296(11):1371–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Comba A, Maestri DM, Berra MA, Garcia CP, Das UN, Eynard AR, et al. Effect of omega-3 and omega-9 fatty acid rich oils on lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenases enzymes and on the growth of a mammary adenocarcinoma model. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:112. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jin Y, Arita M, Zhang Q, Saban DR, Chauhan SK, Chiang N, et al. Anti-angiogenesis effect of the novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(10):4743–52. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Y, Hao H, He S, Cai L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. Lipoxin A4 and its analogue suppress the tumor growth of transplanted H22 in mice: the role of antiangiogenesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(8):2164–74. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang B, Jia H, Liu J, Yang Z, Jiang T, Tang K, et al. Depletion of regulatory T cells facilitates growth of established tumors: a mechanism involving the regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by lipoxin A4. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7199–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsai WH, Shih CH, Wu HY, Chien HY, Chiang YC, Lai SL, et al. Role of lipoxin A4 in the cell-to-cell interaction between all-trans retinoic acid-treated acute promyelocytic leukemic cells and alveolar macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(3):1123–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]