Abstract

Background

African American women are more likely to seek treatment for depression in primary care settings; however, few women receive guideline-concordant depression treatment in these settings. This investigation focused on the impact of depression on overall functioning in African American women in a primary care setting.

Methods

Data was collected from a sample of 507 African American women in the waiting room of an urban primary care setting. The majority of women were well-educated, insured, and employed. The CESD-R was used to screen for depression, and participants completed the 36-Item Short-Form Survey to determine functional status.

Results

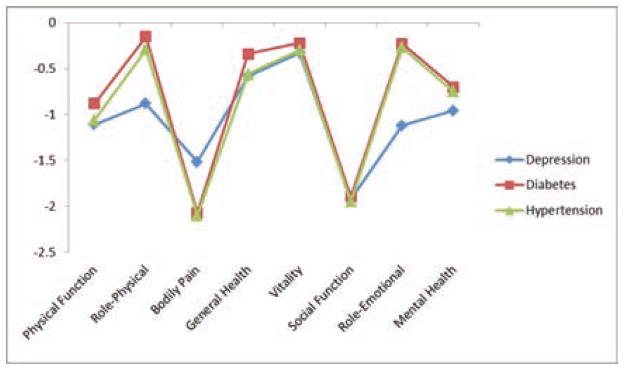

Among the participants with depression, there was greater functional impairment for role-physical (z = −0.88, 95% CI = −1.13, −0.64) when compared to individuals with diabetes and hypertension. Individuals with depression also had greater role-emotional impairment (z=−1.12, 95% CI = −1.37, −0.87) than individuals with diabetes and hypertension. African American women with comorbid hypertension and depression had greater functional impairment in role-physical when compared to African American women with hypertension and no depression (t(124)= −4.22, p<0.01).

Conclusion

African American women with depression are more likely to present with greater functional impairment in role function when compared to African American women with diabetes or hypertension. Because African American women often present to primary care settings for treatment of mental illness, primary care providers need to have a clear understanding of the population, as well as the most effective and appropriate interventions.

Keywords: depression, African American women, primary care

Depression is a major public health problem that has wide-reaching effects on the overall population. The World Health Organization has identified depression as the fourth leading cause of total disease burden and the leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 Unfortunately, few Americans diagnosed with depression receive guideline-concordant treatment, with racial/ethnic minority populations receiving even less treatment than non-Hispanic whites.3

In primary care settings, the treatment of depression in minority populations requires close attention to management and treatment to insure that patients receive quality care. African Americans are more likely to access mental health services from primary care settings rather than in specialty mental health clinics.4,5,6,7 However, primary care physicians are less likely to diagnose and effectively treat depression in general, and specifically in African Americans when compared to non-Hispanic whites.8,9,10,11,12,13

Although conflicting evidence exists, some studies have shown that African Americans have higher rates of depression and greater severity of depressive symptoms when compared to non-Hispanic whites.14,15,16,17 Poorer outcomes following depression treatment were also found when comparing African Americans to non-Hispanic whites.18,19 These findings demonstrate the importance of providing culturally and socially appropriate treatment interventions for patients.

Patient preference may also play a role in the disparities in access to treatment of depression among African Americans. Previous research has found that when compared to non-Hispanic whites, African Americans are less likely to find antidepressant medications to be acceptable treatment for depression.20,21 Although negative beliefs and stigma against mental health treatment were found to be more prevalent among ethnic minority populations, this finding does not explain the racial/ethnic disparities that exist in the acceptability of depression treatment.20,21

Provider bias may also play some role in the lack of diagnosis and treatment of depression in African Americans. In the past, evidence has demonstrated that providers are less likely to detect certain symptoms of mental illness reported by African Americans when compared to non-Hispanic whites.22,23 Greater reporting of somatic symptoms by women and African Americans compared to men and non-Hispanic whites may also contribute to lower rates of treatment.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 Previous research has definitively linked various medical conditions to an increased prevalence in the diagnosis of depression, including diabetes, heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).32,33 Specifically among individuals with comorbid diabetes and depression, African Americans are less likely to use antidepressants than non-Hispanic whites.34,35 This increase in prevalence of depression among individuals with physical illness is associated with greater functional impairment, a 50% increase in medical costs of chronic medical illness, and increased morbidity and mortality.36,37 This association between medical illness and depression further solidifies the role of the primary care provider in the diagnosis and treatment of depression within primary care settings.

Racial-ethnic disparities exist in the prevalence, treatment, and control of many medical conditions that interact with depression. In particular, previous studies have consistently noted a higher incidence overall of type 2 diabetes in African Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites, with even higher rates of diabetes in African American women than African American men.38,39 Recent research has focused on the role of socioeconomic status and environmental risk as the underlying cause of these disparities in diabetes diagnosis and treatment.40,41,42,43 In fact, research has determined that comorbid conditions interact in a multitude of ways among African Americans. For example, African Americans who developed a later diagnosis of diabetes had significantly higher prevalence rates of hypertension than non-Hispanic whites who later developed diabetes.38,39 Similarly, African Americans have lower rates of diagnosis, treatment, and control of hypertension compared to non-Hispanic whites.44,45,46,47,48,49

Because primary care physicians are most likely to encounter patients with comorbid depression and other physical illnesses, it is important to appropriately characterize this population, particularly among racial/ethnically diverse populations. This investigation focused on the impact of depression on overall functioning in a sample of African American women in a primary care setting. Furthermore, we sought to evaluate the impact of depression in African American women with and without comorbid physical illnesses.

METHODS

Design

This study was comprised of a convenience sample, and was conducted in the Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) Comprehensive Family Healthcare Center, a Family Practice Clinic, located in Atlanta, Georgia between May 2000 and July 2002. The primary care site is located in a predominantly residential African American neighborhood, serving primarily African American clients.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Potential participants in the study were approached in the waiting room of the primary care site to determine their interest in participating in a research study involving assessments of functional impairment associated with nine chronic diseases and including screening for depression. Participants were eligible for the study if they were 18 years or older in age, could speak and understand English, and were able to give informed consent.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Revised (CESD-R) was used to screen for depression.50,51 Various versions of the CES-D have been widely used in the past to identify depression across a variety of settings and populations, including African American populations.16,17,52,53,54,55,56,57 The CESD-R is comprised of 20 self-rated items rating symptoms during the past week, including depressed mood (4 items), anhedonia (1 item), somatic symptoms (8 items), cognitive symptoms (6 items), and agitation (1 item). Cut-off scores on the CESD-R are ≤ 8 (not depressed), 9 – 15 (possible depression), and ≥ 16 (probable depression).50,51

Participants also completed the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) which measures functional status in eight domains.58,59 The eight domains are subdivided into two composite scales. The Physical Composite Scale (PCS) is comprised of physical functioning, role-physical, body pain, and general health. The Mental Composite Scale (MCS) includes vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health.58,59 Scores on the SF-36 can range from 0 – 100, with 100 indicating best possible health.58,59,60,61

Participants provided demographic data and a short medical history. Medical chart review was done to confirm the medical history and gather information on diagnosis and clinical management of the participants. All participants gave informed consent before participating in this study, and were provided with a participant stipend.

Study Sample

Data was collected from a sample of 744 adults from the above described clinic. There were 515 African American women in the sample. The CESD-R questionnaire data was present for 50% of women (98.4%). There was no statistical difference in demographic information between the 507 included in the final study sample and the 8 that were excluded due to missing data.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was generated using SAS Version 9.2. Z scores for each of the outcomes standardized to the study populations mean were calculated. We then calculated the means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the Z scores for each of the domains to allow for between group comparisons. Z scores below 0 indicate a decline of functioning compared with the entire participant cohort. Functional impairment of depression was compared with two other common diagnoses in primary care settings, diabetes and hypertension.

We also compared means and CIs for depressed and non-depressed individuals. We performed a t-test to compare means between depressed and non-depressed individuals with hypertension.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the women who participated in the study was 43 years old. The participants were predominantly well-educated, with most having some college education (31.1%), being a college graduate (25.9%), or a technical school graduate (14.7%). Most participants were currently employed (73.2%), and most had insurance coverage (91.6%), with private insurance being most common (71.3%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of African American women presenting to an urban primary care center

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 43.0 ± 12.6 | |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| Less Than High School | 37 | 7.3 |

| High School Graduate | 106 | 21.0 |

| Technical/Vocational School | 74 | 14.7 |

| Some College | 157 | 31.1 |

| College Graduate/Post Graduate | 131 | 25.9 |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

|

| ||

| Never Married | 216 | 43.7 |

| Married | 133 | 26.9 |

| Previously Married | 145 | 29.4 |

|

| ||

| Employment | ||

|

| ||

| Unemployed | 65 | 12.9 |

| Employed | 368 | 73.2 |

| Retired | 18 | 3.6 |

| Disabled | 16 | 3.2 |

| Other | 36 | 7.1 |

|

| ||

| Insurance Status | ||

|

| ||

| Uninsured | 41 | 8.4 |

| Private Insurance | 348 | 71.3 |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 99 | 20.3 |

Figure 1 illustrates the functional impairment in African American women with depression, hypertension, and diabetes. SF-36 Z scores were calculated for each of the eight domains (physical function, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role-emotional, and mental health). Among the participants with depression, there was greater functional impairment for role-physical (z = −0.88, 95% CI = −1.13, −0.64) when compared to individuals with diabetes (z =−0.15, 95% CI = −0.49, 0.19) and hypertension (z=−0.29, 95% CI = -−0.49, −0.10). From the MCS portion of the SF-36, individuals with depression had greater role-emotional impairment (z=−1.12, 95% CI = −1.37, −0.87) than individuals with diabetes (z=−0.23, 95 % CI = −0.58, 0.13) and hypertension (z=−0.27, 95% CI = −0.47, −0.06).

Figure 1.

SF-36 Z scores for African American women with depression, diabetes, and hypertension

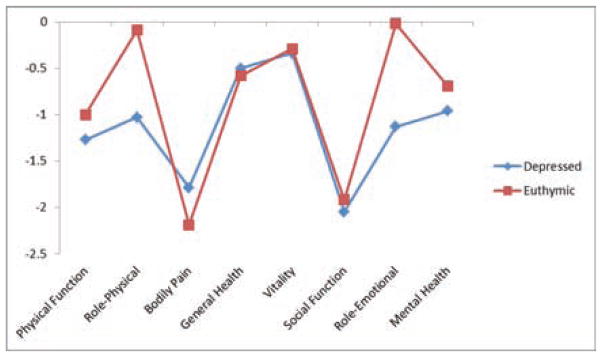

Figure 2 compares African American women with a diagnosis of hypertension who have a diagnosis of depression and those women with hypertension who do not have depression. African American women with comorbid hypertension and depression had greater functional impairment in role-physical (z=−1.03) when compared to African American women with hypertension and no depression (z=−0.09, t(124) = −4.22, p < 0.01). In analyzing mental impairment, African American women with both hypertension and depression had greater impairment in role-emotional (z=−1.13), and mental health (z=−0.96), when compared to the African American women with hypertension and no depression (role-emotional (z=−0.02, t(124) = −4.75, p < 0.01) and mental health (z=−0.69, t(121) = −2.11, p < 0.05)).

Figure 2.

SF-36 Z scores for African American women with hypertension (comparison of depressed and euthymic participants)

DISCUSSION

The present study indicates that women with depression have greater functional impairment than those with hypertension or diabetes in both physical (role-physical) and mental health domains (role-emotional). African American women who have comorbid depression along with hypertension show more functional impairment in role-physical, and the mental health domains of role-emotional and mental health compared to African American women with hypertension and no depression.

The SF-36 defines “role-physical” as “problems with work or other daily activities as a result of physical problems,” and “role-emotional” as “problems with work or other daily activities as a result of emotional problems.” Given the impairment seen among depressed African American women in these areas, our findings confirm that depression can be an extremely disabling condition, affecting an individual’s ability to function effectively in life and work. Those individuals with depression have greater functional impairment in role-physical and role-emotional than those with diabetes or hypertension.

The negative impact of depression on overall physical and mental functioning is evident in our findings comparing functional impairment of African American women with depression to African American women with diabetes and hypertension. These findings support previous research on the harmful impact of comorbid depression on other chronic diseases and overall health.62,63,64,65 While it is standard to assess mental functioning when evaluating an individual for symptoms of depression, primary care providers should consider that their patients may present with significant physical impairment, which may be an important indicator of a possible depression diagnosis. Particularly in examining this population of African American women, greater emphasis may be placed on the impact of depression from a physical impairment perspective, instead of exclusively from an emotional impairment perspective.

Also, in individuals with comorbid medical conditions, even medical conditions that do not always result in objective functional impairment, comorbid depression can lead to worsening mental and physical impairment when compared to individuals without comorbid depression. Among African American women, greater understanding of the impact of mental health and physical health comorbidities helps to inform the appropriate treatment options. It should be stressed that guideline-concordant treatment interventions are effective in the treatment of African American women, so ensuring that these women have access to these treatment modalities should be a priority of primary care providers.66,67

Direct, real-time treatment interventions are often more effective than referrals, and can improve both role and social functioning in African American women.66,67 Effective medication options and therapy is essential. Our findings support that individuals may present with increased role – physical functional impairment. These findings are of particular importance when we consider that previous studies of African American women have demonstrated greater likelihood of dropping out of treatment or opting for psychotherapy over medications for treatment of depression.20,21 Given that this is a highly educated, insured sample of African American women, our findings add another layer of understanding and complexity to the existing body of research that largely examines samples of underinsured or less educated African American women.

Culturally competent interventions that focus on improving role functioning may be of particular significance in this population. Limited research has shown that interpersonal therapy aimed at role disputes and role transitions may be particularly effective; however, more focus is needed in this area.68,69

While interventions on the patient level are important to addressing disparities in the presentation of depression compared to other medical conditions, the role of the provider is essential to improving the overall quality of care provided. Because of the impact of depression on overall health and the complications that untreated depression can contribute to the management of physical illness, it is important for primary care physicians to not only appropriately screen for depression, but to also effectively treat depression when it is encountered in the clinical setting. O’Malley, Forrest, and Miranda (2003) found that African American women who perceived their primary care providers as being respectful had greater odds of being asked about and treated for depression.70 Encouraging primary care providers to view their patients from a whole person, patient-centered perspective can indeed improve the likelihood of more effective treatment of all disease, including depression.

There are limitations associated with this study. While this convenience sample describes a particular subset of African American women in a primary care clinic, these results are by no means fully generalizable to the entire population of African American women in the United States, which are a diverse and heterogeneous collection of individuals. However, there is some benefit to analysis of a population in which there is limited research and evaluation of effectiveness compared to the majority population. Another limitation relates to the population of individuals with diabetes, hypertension, and depression as individuals with discrete diagnoses and not comorbid conditions. Analysis of individuals with all three comorbidities concurrently, while an important endeavor, was beyond the scope of this study.

This study illustrates the need for greater clarity and understanding of the characteristics of depression in African American women. Our findings demonstrate that in a primary care setting, where women may present for various physical health complaints, symptoms of depression may play a significant role in contributing to the decreased physical functioning.

CONCLUSION

With depression continuing to play such a major role in the overall burden of disease in this country, it is imperative that further improvements in screening and interventions need to be made. Furthermore, because African American women often present to primary care settings for treatment of mental illness, primary care providers need to have a clear understanding and characterization of the population, as well as which interventions are most effective for this population. African American women with depression are more likely to present to primary care settings with greater functional impairment in role function, both physical and emotional, when compared to African American women with diabetes or hypertension. Also, African American women with hypertension and depression are more likely to have greater physical and mental functional impairment than African American women with hypertension and euthymic mood. These findings illustrate the critical importance of effectively treating depression in African American women, not only to increase rates of remission and recovery from depression, which is in itself is an important public health priority, but also to decrease overall functional impairment within this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH MRISP MH058272 (D Bradford, PI) and manuscript preparation by R25 MH071735. We would like to thank Monique Haynes for her assistance and support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors each report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Ruth S. Shim, National Center for Primary Care, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Peter Baltrus, National Center for Primary Care, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

L. DiAnne Bradford, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, Department of Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Kisha B. Holden, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Edith Fresh, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Lonnie E. Fuller, Sr., Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Depression. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- 3.Gonzalez H, Vega W, Williams D, et al. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snowden L, Pingitore D. Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African Americans in primary care. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4(3):123–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1019709728333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper LA, Dinoso BKG, Ford DE, Roter DL, Primm AB, Larson SM, Gill JM, Noronha GJ, Shaya EK, Wang N-Y. Comparative effectiveness of standard versus patient-centered collaborative care interventions for depression among African-Americans in primary care settings: The BRIDGE Study. Health Services Research. 2013;48(1):150–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alegria M, Canino G, Ríos R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs HE, Briggs AC, Miller KM, Paulson RI. Combating persistent cultural incompetence in mental health care systems serving African- Americans. Best Practice in Mental Health. 2011;7(2):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borowsky S, Rubenstein L, Meredith L, et al. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(6):381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gitlin LN, Harris LF, McCoy M, Chernett NL, Jutkowitz E, Pizzi LT. A community-integrated home based depression intervention for older African Americans: Description of the Beat the Blues randomized trial and intervention costs. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12(4) doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwenk T, Evans D, Laden S, et al. Treatment outcome and physician-patient communication in primary care patients with chronic, recurrent depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(10):1892. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hails K, Brill CD, Chang T, Yeung A, Fava M, Trinh N-H. Cross-cultural aspects of depression management in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:336–344. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ani C, Bazargan M, Hindman D, et al. Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settings. BMC Family Practice. 2008;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter-Song E, Whitley R, Lawson W, Quimby E, Drake RE. Reducing disparities in mental health care: Suggestions from the Dartmouth–Howard collaboration. Community Ment Health. 2011;47:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslau J, Kendler K, Su M, et al. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(03):317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker LS, Satkoske VB. Ethical dimensions of disparities in depression research and treatment in the pharmacogenomics era. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2012;40(4):886–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2012.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams D, Gonzalez H, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henning-Smith C, Shippee TP, McAlpine D, Hardeman R, Farah F. Stigma, discrimination, or symptomatology differences in self-reported mental health between US-Born and Somalia-Born Black Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):1–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown C, Schulberg H. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary medical care practice: the application of research findings to clinical practice. Journal of clinical psychology. 1998;54(3):303–314. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199804)54:3<303::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jutkowitz E, Pizzi L, Hess E, Suh D-C, Gitlin LN. Comparison of three societally derived health-state classification values among older African Americans with depressive symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0263-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper L, Gonzales J, Gallo J, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesser IR, Zisook S, Gaynes, Wisniewski SR, Luther JF, Fava M, Khan A, McGrath P, Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi M. Effects of race and ethnicity on depression treatment outcomes: The CO-MED Trial. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:1167–1179. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.10.pss6210_1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold L, Keck P. Ethnicity and first-rank symptoms in patients with psychosis. Schizophrenia research. 2004;67(2–3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulvaney-Day NE, Earl TR, Diaz-Linhart Y, Alegria M. Preferences for relational style with mental health clinicians: A qualitative comparison of African American, Latino and Non-Latino White patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67(1):31–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magni E, Frisoni G, Rozzini R, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms in the elderly: the role of cognitive function. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1996;11(6):517–522. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris AA, Zhao L, Ahmed Y, Stoyanova N, De Staercke C, Hooper WC, Gibbons G, Din-Dzietham R, Quyyumi A, Vaccarino V. Association between depression and inflammation--differences by race and sex: The META-Health Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73:462–468. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318222379c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverstein B. Gender differences in the prevalence of somatic versus pure depression: a replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):1051. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delisle VC, Beck AT, Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, Thombs BD. Revisiting gender differences in somatic symptoms of depression: Much ado about nothing? PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel A, Steer R, Beck A. Are there any gender differences in frequency of self-reported somatic symptoms of depression? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89(1–3):177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao U, Poland RE, Lin K-H. Comparison of symptoms in African-American, Asian-American, and Mexican-American and Non-Hispanic White patients with major depressive disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwata N, Turner R, Lloyd D. Race/ethnicity and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling young adults: a differential item functioning analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2002;110(3):281–289. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott T, Matsuyama R, Mezuk B. The relationship between treatment settings and diagnostic attributions of depression among African Americans. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon W, Ciechanowski P. Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):859–864. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akincigil A, Olfson M, Siegel M, Zurlo KA, Walkup JT, Crystal S. Racial and ethnic disparities in depression care in community-dwelling elderly in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(2):319–328. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborn CY, Trott HW, Buchowski MS, et al. Racial disparities in the treatment of depression in low-income persons with diabetes. Diabetes care. 2010;33(5):1050. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborn CY, Patel KA, Liu J, Trott HW, Buchowski MS, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ, Cohen SS, Schlundt DG. Diabetes and co-morbid depression among racially diverse, low-income adults. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(3):300–309. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katon W. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katon W. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2011;13(1):7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brancati FL, Kao W, Folsom AR, et al. Incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American and white adults. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(17):2253. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes L, Hossain J, Ward D, Opara F. Racial/Ethnic Variability in Hypertension Prevalence and Risk Factors in National Health Interview Survey. ISRN Hypertension. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ, Galarraga JE, et al. Environmental and socio-economic factors as contributors to racial disparities in diabetes prevalence. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(10):1144–1148. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hicken M, Gee G, Movenoff J, Connell C, Snow R, Hu H. A Novel Look at Racial Health Disparities: The Interaction Between Social Disadvantage and Environmental Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(12):2344–2351. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Signorello LB, Schlundt DG, Cohen SS, et al. Comparing diabetes prevalence between African Americans and Whites of similar socioeconomic status. American journal of public health. 2007;97(12):2260. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sims M, Roux A, Boykin S, Sarpong D, Gebreab S, Wyatt S, Hickson D, Payton M, Ekunwe L, Taylor H. The Socioeconomic Gradient of Diabetes Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control among African American in Jackson Heart Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2011;21(12):892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wyatt SB, Akylbekova EL, Wofford MR, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):650. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boykin S, Roux A, Carnethon M, Shrager S, Ni H, Grover M. Racial/Ethnic Heterogeneity in the Socioeconomic Patterning of CVD Risk Factors: in the United States: The Multi-Ethic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):111–127. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosworth HB, Powers B, Grubber JM, et al. Racial differences in blood pressure control: potential explanatory factors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):692–698. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redmond N, Baer H, Hicks L. Health Behaviors and Racial Disparity in Blood Pressure Control in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2011;57:383–389. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mujahid MS, Roux AVD, Cooper RC, et al. Neighborhood Stressors and Race/Ethnic Differences in Hypertension Prevalence (The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) American Journal of Hypertension. 2010;24(2):187–193. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosworth H, Olsen M, Grubber J, Powers B, Oddone E. Racial Differences in Two Self-Management Hypertension Interventions. The American Journal of Medicine. 2011;124 (5):468.e1–468.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallo J, Rabins P. Depression without sadness: alternative presentations of depression in late life. American Family Physician. 1999;60:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renn B, Feliciano L, Segal D. The bidirectional relationship of depression and diabetes: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(8):1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown C, Schulberg H, Madonia M. Clinical presentations of major depression by African Americans and whites in primary medical care practice. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;41(3):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kravitz R, Paterniti D, Epstein R, Rochlen A, Bell R, Cipri C, Garcia E, Feldman M, Duberstein P. Relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;82(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gallo J, Bogner H, Morales K, et al. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165(17):1962. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dam N, Earleywine M. Validation of the Center for Epidemologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R): Pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186 (1):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallo J, Bogner H, Morales K, et al. Depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and 2-year mortality among older primary care patients. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2005;13(9):748. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis T, Yang F, Jacobs E, Fitchett G. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Responses to the Everyday Discrimination Scale: A Differential Item Functioning Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;175(5):391–401. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ware J. Measuring Patients’ Views: The Optimum Outcome Measure: SF 36: A Valid, Reliable Assessment Of Health From The Patient’s Point Of View. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1993;306(6890):1429–1430. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Green J, Kosinski M, Gandek B, Ware J. Validation testing of a three-component model of Short Form-36 scores. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(3):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McHorney C, Ware J, Lu J, et al. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.IsHak W, Greenburg J, Balayan K, Kapitanski N, Jeffrey J, Fathy H, Fakhry H, Rapaport M. Quality of Life: The Ultimate Outcome Measure of Interventions in Major Depressive Disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):229–239. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.614099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Markowitz S, Gonzalez J, Wilkinson J, Safren S. A Review of Treating Depression in Diabetes: Emerging Findings. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Egede LE. Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among US adults. Diabetes care. 2004;27(2):421. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campayo A, Gomez-Biel C, Lobo A. Diabetes and Depression. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13(1):26–30. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0165-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miranda J, Chung J, Green B, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Waerden J, Hoefnagels C, Hosman C. Pyschosocial preventive interventions to reduce depressive symptoms in low-SES women at risk: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;128(1–2):10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown C, Schulberg H, Sacco D, et al. Effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary medical care practice: a post hoc analysis of outcomes for African American and white patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;53(2):185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kupfer D, Frank E, Phillips M. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. The Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1045–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Malley A, Forrest C, Miranda J. Primary care attributes and care for depression among low-income African American women. American journal of public health. 2003;93(8):1328. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]