Abstract

A model study of the first non-aromatic ring based approach toward α-hydroxyspiroisoxazolines resembling the bromotyrosine derived natural product and analogous spiroisoxazoline core structures were implemented. The desired molecular architecture was achieved through the multifunctionalization of a key 1,3-diketo spiroisoxazoline. Our strategy could serve as an efficient alternative of previously developed approaches that utilize an aromatic ring oxidation as the essential step to synthesize this class of natural products.

Keywords: Heterocycles, Natural Product Analogues, Spiroisoxazolines, Multifunctionalization, Intramolecular Cyclization

Introduction

Over the past 50 years, marine sponges of the order Verongida have been distinguished as affluent sources of α-oximinotyrosine derived marine natural products (Figure 1).[1] Most recently, the Red Sea sponge Suberea mollis were also found to be a source of two new bromotyrosine derived natural products, subereamollines A and B, as secondary metabolites containing the spiro-cyclohexadienyl isoxazoline moiety.[2] These widespread spiroisoxazoline natural products can easily be distinguished by three major structure categories, where the brominated spiroisoxazoline core contains a cyclohexadiene, bromo epoxy ketone, or a bromohydrin moiety (Figure 1). The structural diversity arising from a unique spiro linkage between a brominated cyclohexadiene, an ioxazoline along with a wide range of amine and diamine linkages, brings about a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities including antiviral,[3] antimicrobial,[4] anti-HIV,[5] antifungal,[6] antifouling,[7] Na+/K+ ATPase inhibition,[8] histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition,[9] histamine H3 antagonism,[10] mycothiol S-conjugate amidase inhibition,[11] isoprenylcysteine carboxy methyltransferase (Icmt) inhibition,[12] and antineoplastic properties.[13]

Figure 1.

Spiroisoxazoline natural products.

Therefore, constructing the unique and synthetically challenging spiro-skeleton has been of great interest to many chemists.[14],[15] However, continuing efforts resulted in only a few synthetic strategies for the syntheses of functionalized carbocyclic spiroisoxazolines.[15] Although significant progress in the oxidation of an aromatic ring with thallium(III) trifluoroacetate,[15a,b] electro-organic oxidation[15c,d] and N-bromosuccinimide[15f] followed by the intramolecular cyclization of a pendant oxime has been achieved in past decades, the oxidative methods for spiroisoxazoline synthesis remain restricted to aromatic systems where the desired products are sometimes isolated in moderate yields and often required the use of toxic oxidants.[15a–d] However, the oxidative cyclization of oxime ester using diacetoxyiodo benzene was proven to be the most suitable reagent to date.[15e,g–i]

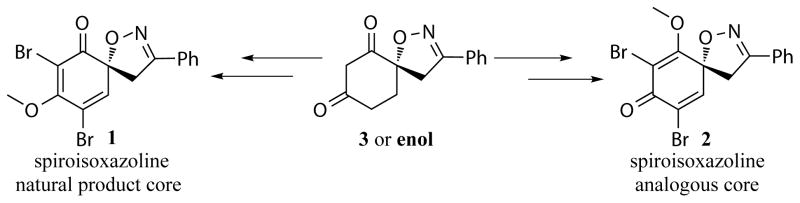

In this context, our continuing efforts and success in developing a new methodology[16] enabled us to generate a novel synthetic strategy toward the bromotyrosine class of natural products (Scheme 1). Herein, we report the multifunctionalization approach of a 1,3-cyclohexane-dione to furnish the desired spiroisoxazoline as a model study for the core structure of bromotyrosine derived spiroisoxazoline natural products and their analogues (Scheme 1). Furthermore, this methodology could potentially serve as an alternative synthetic strategy toward the targeted natural products and closely related spiroisoxazolines as novel analogues of biological interest.

Scheme 1.

Our synthetic strategy.

Results and Discussion

Our synthesis basically relies on two approaches, a non aromatic approach towards the spiro-diketone followed by a multifunctionalization approach to furnish the desired molecular architecture resembling the bromotyrosine derived natural product core. The retrosynthetic analysis of the aforementioned natural product core model study shows that the most synthetically interesting core spiroisoxazolines 1 and 2 could be obtained from their corresponding spiro-methoxyenone derivatives 4 and 5 which in turn could be achieved from the same spiro-1,3-diketone moiety 3. The spiro-diketone 3 would be easily prepared from a base mediated intramolecular condensation of the corresponding ketoester 6 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis.

In our synthesis, acyclic isoxazole derivative 6[16b,17] was used as a key precursor for this model study. After reacting 6 with sodium hydride, the diketone spiroisoxazoline 3 was isolated in 80% yield (Scheme 3). The 1H NMR study showed that compound 3 exists as an enol which results in the fast exchange of one of the protons between the two carbonyl groups. It is worth noting that the ready availability of cyclohexane-1,3-dione, and its diverse reactivity, often render cyclohexane-1,3-dione, and its analogues, as suitable starting materials for a number of natural product syntheses.[18] However, for our synthetic strategy, we need to convert the diketone into a conjugated diene system for additional functionalization.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the spiro-vinylogous acid of 3.

We subjected 3 to a variety of reported reaction conditions[19] to determine the best reagent that would afford spiroisoxazoline regioisomers 4 and 5 in the highest isolated yields (Table 1). Based upon the data shown in Table 1, entry 4, which features 5 mol% TiCl4 in methanol[19d] with triethyl amine, both spiroisoxazolines, 5 and 4, were isolated in 97% yield in a 1: 2.5 ratio favoring the spiroisoxazoline 4 after 15 minutes (Table 1). Due to the fact that both regioisomers were isolated, divergent synthetic pathways were explored where spiroisoxazoline 4 was utilized as a precursor for the natural product core structure (analogous to 11-deoxyfistularin-3), while spiroisoxazoline 5 was developed into a spiroisoxazoline that is more comparable to the agelorin natural products where the carbonyl and isoxazoline moieties have a 1,4-relationship.[21]

Table 1.

Synthesis of methoxyenone.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Procedure | Ratio (5:4) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | 10% HCl/MeOH | 1:2 | 50 |

| 2 | Conc. H2SO4/MeOH, reflux 12h | 1:2 | 70 |

| 3 | 2.5 mol% pTSA/MeOH, reflux 6h | 1:1.5 | 60 |

| 4 | 5 mol% TiCl4/MeOH/Et3N reflux 6h | 1:2.5 | 97 |

| 5 | CeCl3.7H2O/MeOH, 6 min | 1:2 | 40 |

| 6 | NaH/THF, reflux 2h, then Me2SO4 | 1:2 | 82 |

| 7 | tBuOK/THF, 10 min, then Me2SO4 | 1:2.5 | 80 |

With the anticipation of furnishing a conjugated double bond, we treated the predominant isomer 4 with LHMDS, PhSeCl followed by H2O2.[20,22] As a result, deprotonation of the allylic proton of 4 and subsequent formation and elimination of the selenoxide afforded 8 in 75% yield (Scheme 4). In order to accomplish the core structure, the spiro-diene was then exposed to a number of reaction conditions to bring about di-bromination and concomitant dehydrohalogenation. Unfortunately, after a number of attempts to introduce bromine to 8 through a variety of bromine sources (pyridinium tribromide (PTB)/K2CO3, Br2/CCl4, NBS/CCl4), none of the desired product 1 was isolated, instead a decomposition of the starting material was realized (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

1st Generation synthesis of spirodiene.

Isomer 5 was also treated under a comparable reaction series as shown in Scheme 4 in order to introduce the other double bond to furnish the natural product derivative as a model study for the synthesis of the spiroisoxazoline analogue (Scheme 5). While the isomer 5 was treated with LHMDS, PhSeCl followed by H2O2, we isolated spiro-derivative 9 in 71% yield (Scheme 5). Bromination of 9 with bromine in the absence of light afforded the vicinal dibromo derivative, 10[23] in 90% yield, as result of over bromination followed by dehydrohalogenation. We did not realize any dibromination of each α-carbon with respect to the ketone as an expected product 2. The feasibility of introducing the third bromine at α-position of 10 was further experienced under PTB/K2CO3 conditions to afford the 11 in 82% yield (Scheme 5). However, our target was to synthesis 1,3-dibromo derivative of spiroisoxazoline 2.

Scheme 5.

1st Generation synthesis of bromo-spiroisoxazoline.

After this setback, we then decided to switch the electrophile used in the synthesis of 1 from phenylselenium chloride to bromine. We anticipated that after reacting 4 with excess (2.5 equiv.) LHMDS followed by treatment with excess bromine would provide the allylic geminal dibromo compound 12 via monobromination. Therefore, we followed this reaction pathway, and, without further purification, the crude allylic geminal dibromo compound 12 was reacted with DABCO in situ to afford 13 in 76% yield over two steps in one reaction vessel (Scheme 6). Bromination of 13 adjacent to the carbonyl was achieved in 76% with NBS in the dark. Diastereoselective reduction of 1 with Zn(BH4)2[24] afforded the desired spiroisoxazoline core structures (±)-14 and (±)-15 in a 4:1 diastereomeric ratio (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

2nd Generation synthesis of bromo-spiroisoxazoline core.

Purification of the crude mixture gave (±)-14 and (±)-15 in a yield of 64% and 16%, respectively. The diastereomeric ratio favoring the desired trans-isomer 14 over the undesired cis-isomer 15 was rationalized by intramolecular hydride delivery through a 5-membered zinc chelate that avoids the steric demands of the isoxazoline methylene group, resulting in the delivery of the hydride from the alpha face of the ketone.[25] Though we have synthesized the racemic 14 and 15, the rigid scaffold of the spiro-isoxazolines showed signs of distinct nOe interactions between the diagnostic protons which enabled us to establish the relative stereochemical assignment of the hydroxyl group on the basis of the NOESY spectrum (Scheme 6). The distinct nOe interactions indicated strong cross peaks between H5 and H7 for compound 14, whereas, in the case of 15, strong cross peaks were observed between H5 and H7, and also between H1 and H8, which suggested the formation of trans-isomer 14 and cis-isomer 15 as a result of diastereoselective reduction (Scheme 6).

Having succeeded in constructing the desired spiroisoxazoline 1 through our model studies, we then focused on transforming the minor isomer 5 to its corresponding dibromo derivative 2 (Scheme 7). Following a similar protocol that was used in Scheme 6, compound 5 was treated with excess LHMDS and Br2 followed by DABCO under reflux conditions to provide the desired mono-bromo-derivative 17 in 78% yield. Further bromination of 17 using PTB/K2CO3 provided the desired α-dibromo derivative 2 in 80% yield (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

2nd Generation synthesis of quinone-spiroisoxazoline core.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully accomplished the synthesis of the core skeleton that is very similar to naturally available spiroisoxazolines, such as 11-deoxyfistularin-3, as well as the isomeric spiroisoxazoline core where the isoxazoline moiety and carbonyl are positioned in a similar fashion as agelorin A and B. The diverse reactivity of the key 1,3-diketo-spiroisoxazoline precursor enabled us to quickly furnish the desired molecular structures in good to very good isolated yields. Due to the success of this model study, we are positioned to imminently apply the reported synthetic methodology from this model system toward the syntheses of spiroisoxazoline containing natural products as well as their synthetic analogues for biological evaluation.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

Unless otherwise stated, all solvents and reagents were commercially obtained and were used without prior purification. The progression of reaction was monitored by analytical thin-layer chromatography using 60Å silica gel medium and 250μm layer thickness, and compounds were visualized by 254 nm light, basic KMnO4 (40g of K2CO3 + 6g of KMnO4 in 600mL of water, then 5mL of 10% NaOH added) and subsequent development with either gentle or no heating. The crude products were purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel (60 Å, 0.060–0.200 mm) by using the required hexanes and ethyl acetate ratio as the eluent system. All NMR spectra were measured at 25 °C in the indicated deuterated solvents.1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in 500 MHz and 125 MHz respectively. The NMR data are reported as follows: proton and carbon chemical shifts (δ) in ppm using tetramethylsilane as an internal standard, coupling constants (J) in hertz (Hz), and resonance multiplicities (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, and m = multiplet). The residual protic solvent of CDCl3 (1H, δ 7.26 ppm); (13C, δ 77.0 ppm central resonance of the triplet), and C3D6O (1H, δ 2.05 ppm; 13C, δ 29.84 ppm) were used as the internal references in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Melting points are uncorrected. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were measured on neat NaCl. The absorptions are given in wave numbers (cm-1). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analyses were performed on the basis of positive electrospray ionization. Either protonated molecular ions [M + nH]n+ or sodium adducts [M + Na]+ were used for empirical formula confirmation.

1,3-Diketo-spiroisoxazoline (3)

To a stirred solution of the isoxazoline 6 (1.0 g, 3.45 mmol) in anhydrous toluene (80 mL) was added a 60% dispersion of sodium hydride (0.42 g, 9.94 mmol) in mineral oil. The reaction mixture was then heated to 80 °C and stirred overnight. After the disappearance of starting material, as evidenced by TLC, the reaction mixture was quenched with 1N HCl (20 mL). The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (20 mL), dried over MgSO4, filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel using 1:1 hexanes–ethyl acetate as an eluant to provide dione 3 as a pale yellow solid (0.672 g, 80% yield). Rf = 0.33 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). mp 163–165 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C3D6O): δ = 7.73–7.72 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.44 (m, 3H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 3.97 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.20 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 2.82–2.76 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.44 (m, 1H), 2.4–2.35 (m, 1H), 2.24–2.18 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, C3D6O): δ= 206.3, 156.8, 130.8, 130.7, 129.5, 127.4, 104.0, 86.4, 41.3, 32.7, 27.8. IR (KBr ): νmax = 3200, 3072, 3023, 2945, 2913, 1728, 1645, 1609, 1357, 1322, 1247, 1203, 918, 764, 692 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C14H13NO3 (M+Na+): 266.0787; found 266.0787.

Spiro-methoxyenones (4 and 5)16b

To a well stirred solution of the cyclic 1,3-diketone 3 (1.15 g, 4.75 mmol) in MeOH (5 mL) was added TiCl4 (0.23 mL, 1M in CH2Cl2) in one portion with a syringe, at room temperature, The reaction mixture was then stirred for an additional 30 min before the addition of Et3N (0.8 mL, 0.57 mmol). The stirring was continued for additional 45 min before addition of H2O (3 mL). The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL) and the combined organic layers were successively washed with H2O (3 × 100 mL), brine, dried over MgSO4 filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was purified by flash column over silica gel using 3:1 hexanes–ethyl acetate as an eluent to afford 5 and 4 as a separable mixture (1:2.5) of two diastereomers in 97% isolated yield.

Spiro–diene (8)

To a solution of methoxyenone 4 (0.285 g, 1.1 mmol) in anhydrous THF (35 mL) at −78 °C was added slowly a solution of LHMDS (1.65 mL, 1M in THF). The resulting solution was allowed to warm to −10 °C over a period of 1h. After re-cooling to −78 °C, a solution of PhSeCl (0.316 g, 1.65 mmol) in anhydrous THF was added slowly. The solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C over a period of 30 min. At this stage TLC observation showed the formation of a less polar intermediate selenide. Once this conversion was complete, saturated aq. NH4Cl (1.0 mL) and 31% aq. H2O2 (2.8 mL) were added, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 45 °C. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (50 mL), and the layers were separated. The organic phase was washed with H2O (50 mL) and brine (50 mL) and then dried (MgSO4). The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel using 4:1 hexanes–ethyl acetate as an eluent to obtain diene 8 as yellow oil (0.212 g, 75% yield). Rf = 0.56 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.67–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.40 (m, 3H), 6.50 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (dd, J = 10.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 5.50 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.73 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 196.2, 170.6, 155.1, 139.5, 130.4, 128.8, 128.7, 127.0, 123.7, 98.4, 82.9, 56.3, 46.0. IR (thin film): νmax = 3015, 2949, 2923, 2851, 1733, 1576, 1457, 1356, 1249, 1214, 898, 756 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H13NO3 (M+Na+): 278.0787; found 278.0787.

Spiro-derivative (9)

To a solution of methoxyenone 5 (0.100 g, 0.388 mmol) in anhydrous THF (15 mL) at −78 °C was added slowly a solution of LHMDS (0.6 mL, 1M in THF). The resulting solution was allowed to warm to −10 °C over a period of 1h. After re-cooling to −78 °C, a solution of PhSeCl (0.110 g, 0.574 mmol) in anhydrous THF was added slowly. The solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C over a period of 30 min. At this stage TLC observation showed the formation of a less polar intermediate selenide. Once this conversion was complete, saturated aq. NH4Cl (1.0 mL) and 31% aq. H2O2 (1.0 mL) were added and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 45 °C. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (50 mL) and the layers were separated. The organic phase was washed with H2O (50 mL) and brine (50 mL) and then dried (MgSO4). The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel using 3:1 hexanes–ethyl acetate as an eluent to obtain diene 9 as yellow oil (0.070 g, 71% yield). Rf = 0.50 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ= 7.68–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.45 (m, 3H), 6.71 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (s, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.75 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 186.7, 171.2, 155.8, 141.8, 130.6, 128.9, 128.5, 128.0, 126.9, 102.3, 80.9, 56.2, 44.5. IR (thin film): νmax = 3015, 2949, 2921, 2855, 1728, 1572, 1458, 1254, 1217, 898, 747 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H13NO3 (M+Na+): 278.0787; found 278.0787.

1,2-Dibromo spiro-derivative (10)

To a solution of 9 (0.024 g, 0.098 mmol) in CCl4 was added Br2 (0.012 mL, 2.5 equiv.). The resulting mixture was stirred in the dark for overnight at rt. Then the solvent and gaseous product was reduced under pressure. The yellow residue was dissolved in Et2O and washed with Al2O3 and evaporated. The crude mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography using 12% ethyl acetate in hexanes as an eluent to obtain the pure compound 10 as pale yellow solid (0.036 g, 90% yield). Rf = 0.67 (3:1 hexanes/EtOAc). mp 123–125 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.69 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.47–7.45 (m, 3H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 3.82 (br s, 5H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 176.6, 171.6, 155.5, 142.4, 130.8, 130.4, 128.9, 128.1, 127.0, 100.3, 85.5, 57.1, 47.2. IR (KBr): νmax = 3068, 3020, 2949, 2925, 2853, 1723, 1661, 1637, 1582, 1447, 1358, 1216, 756 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H11Br2NO3 (M+Na+): 433.8997; found 433.8996.

Tribromo spiro-derivative (11)

A solution of 10 (0.032 g, 0.080mmol) and K2CO3 (0.032g, 0.238 mmol) in 2 mL of dry dichloromethane was stirred in an ice-water bath. Pyridinium tribromide (0.74 g, 0.232 mmol) was added slowly to the cold mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C, and was allowed to slowly warm to rt overnight. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt until the disappearance of the starting materials, as evidenced by TLC. The reaction mixture was poured into a cold, saturated NH4Cl solution (5 mL), extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL), and washed with a saturated CuSO4 solution (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude products were purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel using the 6% ethyl acetate in hexanes as an eluent to obtain the pure compound 11 as pale yellow solid (0.028 g, 82% yield). Rf = 0.67 (3:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.69 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.50–7.45 (m, 3H), 4.16 (s, 3H), 3.91 (d, J =17.1 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 172.1, 168.7, 156.2, 143.8, 131.0, 129.0, 128.1, 127.9, 127.1, 108.5, 85.3, 63.2, 46.8. IR (KBr): νmax =2949, 2919, 2849, 1733, 1664, 1616, 1578, 1354, 1218, 1051, 946, 889, 763, 692 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H10Br3NO3 (M+Na+): 511.8103; found 511.8104.

Monobromo spiroisoxazoline (13)

To a previously cooled (−78 °C) solution of 4 (0.698 g, 2.73 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) was added slowly a solution of LHMDS (8.0 mL, 1M in THF). The resulting solution was allowed to warm to −10 °C over a period of 1h. After re-cooling to −78 °C, a solution of bromine (0.42 mL, 8.2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added slowly to the reaction mixture. The solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C over a period of 30 min. TLC observation showed the formation of a less polar bromo intermediate. Once this conversion was complete, DABCO (0.612 g, 5.46 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture, and the resulting mixture was refluxed for 3h. After the disappearance of the less polar material, as evidenced by TLC, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (50 mL) and washed with H2O (10 mL), brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by flash column over silica gel using 4:1 hexanes-ethyl acetate as an eluent to afford 13 (0.693 g, 76% yield) as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.65 (3:2 hexanes/EtOAc). mp 154–156 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.66–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.39 (m, 3H), 6.88 (s, 1H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.75 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 194.7, 165.4, 155.2, 139.8, 130.6, 128.8, 128.5, 127.0, 117.8, 99.2, 84.5, 57.3, 45.7. IR (KBr): νmax = 3076, 3023, 2978, 2945, 1652, 1575, 1368, 1254, 1209, 1001, 759, 689 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H12BrNO3 (M+Na+): 355.9892; found 355.9894.

Spiroisoxazoline (1)

To a solution of 13 (0.327 g, 0.976 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added NBS (0.230 g, 1.95 mmol) and the resulting mixture was stirred for 24 h at rt under dark reaction conditions. Completion of the reaction was monitored by TLC analysis. The reaction mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and washed with H2O (50 mL), saturated Na2S2O3 (2 × 50 mL), brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column over silica gel using 6% ethyl acetate in hexanes as an eluent to afford 1 (0.306 g, 76% yield) as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.73 (3:2 hexanes/EtOAc). mp 140–142 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.64–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.39 (m, 3H), 6.86 (s, 1H), 4.16 (s, 3H), 3.77 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 3.44 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 189.9, 163.2, 155.4, 137.7, 130.8, 128.7, 128.2, 126.9, 119.5, 107.4, 85.2, 61.9, 45.0. IR (KBr): νmax = 3068, 2949, 2937, 2851, 1683, 1541, 1322, 894, 761, 692, 538 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H11Br2NO3 (M+Na+): 433.8997; found 433.9001.

Spiroisoxazoline Core (14 and 15)

To a stirred solution of 1 (0.275 g, 0.67 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) at room temperature was added a freshly prepared solution of Zn(BH4)2 (1.0 mL, 0.25 M in Et2O).23 After 10 min, H2O (0.5 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for a further 30 min. Following the addition of anhydrous MgSO4, the mixture was filtered and concentrated in vacuo. NMR of the crude product shows the formation of 14 and 15 in a 4:1 diastereomeric mixture. The crude residue was purified carefully by flash column chromatography over silica gel using 10% ethyl acetate in hexanes to obtain (±)14 (0.178 g, 64% yield) and (±)15 (0.045 g, 16% yield) as a colorless liquid.

Mixture of 14 and 15

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.66–7.62 (m, 2.5H), 7.44–7.38 (m, 4.75H), 6.44 (s, 0.25H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 4.50 (s, 1H), 4.41 (s, 0.25H), 4.09 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1.25H), 3.78 (s, 0.75H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.11 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1.25H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 157.2, 157.1, 148.4, 148.1, 132.2, 131.6, 130.7, 130.5, 128.9, 128.8, 128.7 (2C), 126.8, 126.7, 120.8, 120.4, 112.93, 112.5, 89.4, 87.7, 75.2, 74.1, 60.13, 60.1, 44.1, 40.1.

Spiroisoxazoline Core (14)

Rf = 0.70 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.67–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.43–7.39 (m, 3H), 6.41 (s, 1H), 4.51 (s, 1H), 4.09 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.12 (d, J = 17.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 157.1, 148.2, 132.2, 130.5, 128.9, 128.8, 126.8, 120.4, 112.4, 89.2, 74.2, 60.1, 40.1. IR (thin film): νmax = 3384, 3056, 3007, 2934, 2839, 1577, 1447, 1359, 1309, 1217, 984, 905, 760, 691 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H13Br2NO3 (M+Na+): 435.9154; found 435.9159.

Spiroisoxazoline Core (15)

Rf = 0.63 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.65–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.40 (m, 3H), 6.45 (s, 1H), 4.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H–OH). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 157.1, 148.4, 131.5, 130.7, 128.9, 128.5, 126.8, 120.9, 112.4, 87.7, 75.2, 60.1, 44.2. IR (thin film): νmax = 3374, 3060, 3011, 2933, 2835, 1576, 1442, 1356, 1307, 1213, 980, 902, 759, 690 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H13Br2NO3 (M+Na+): 435.9154; found 435.9157.

Mono bromo spiro-derivative (17)

To a previously cooled (−78 °C) solution of 5 (0.660 g, 2.56 mmol) in anhydrous THF (15 mL) was added slowly a solution of LHMDS (6.5 mL, 1M in THF). The resulting solution was allowed to warm to −10 °C over a period of 1h. After re-cooling to −78 °C, a solution of bromine (0.33 mL, 6.4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) was added slowly to the reaction mixture. The solution was allowed to warm to 0 °C over a period of 30 min. TLC observation showed the formation of a less polar bromo intermediate. Once this conversion was complete, DABCO (0.574 g, 5.08 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture, and the resulting mixture was refluxed for 3h. After the disappearance of the less polar material, as evidenced by TLC, the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (50 mL) and washed with H2O (10 mL), brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified by flash column over silica gel using 4:1 hexanes-ethyl acetate as an eluent to afford 17 (0.667 g, 78% yield) as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.62 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.65 (d, J = 6.35 Hz, 2H), 7.46–7.40 (m, 3H), 7.14 (s, 1H), 5.71 (s, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.76 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 3.51 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 178.8, 171.1, 155.8, 141.5, 130.7, 128.9, 128.2, 126.9, 125.1, 101.2, 82.8, 56.6, 44.7. IR (KBr): νmax = 3060, 2922, 2851, 1733, 1645, 1598, 1445, 1357, 1209, 901, 757, 689 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H12BrNO3 (M+Na+): 355.9892; found 355.9895.

Dibromo spiro-derivative (2)

A solution of 17 (0.300 g, 0.89 mmol) and K2CO3 (0.307 g, 2.22 mmol) in 10 mL of dry dichloromethane was stirred in an ice-water bath. Pyridinium tribromide (0.574 g, 1.79 mmol) was added slowly to the cold mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C, and was allowed to slowly warm to rt overnight. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt until the disappearance of the starting materials, as evidenced by TLC. The reaction mixture was poured into a cold, saturated NH4Cl solution (50 mL), extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 mL), and washed with saturated CuSO4 solution (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was dried with MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude products were purified by flash column chromatography over silica gel using 5% ethyl acetate in hexanes as an eluent to obtain the pure compound 2 as a white solid (0.294 g, 80% yield). Rf = 0.80 (3:2 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.67–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.48–7.57 (m, 3H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 4.16 (s, 3H(, 3.85 (dd, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 173.8, 167.8, 156.5, 142.4, 131.0, 129.0, 128.1, 126.9, 122.8, 108.8, 85.6, 62.5, 43.8. IR (KBr): νmax = 3060, 2921, 2847, 1683, 1540, 1319, 1278, 1229, 951, 890, 763, 690 cm−1. HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for C15H11Br2NO3 (M+Na+): 433.8997; found 433.9001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Award Number: SC3GM094081-04) and the Analytical and NMR CORE Facilities were supported by National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources (Award Number: G12RR013459) and National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Award Number: G12MD007581).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.xxxxxxxxx.

Supporting Information (see footnote on the first page of this article): … . Characterization data (1H and 13C NMR spectra) for all new compounds, 2D NMR (NOESY and HMBC) spectra for 14 and 15 and CCDC 967652 for X-ray crystal structures of 10.

References

- 1.a) Berquist PR, Wells RJ. Chemotaxonomy of the Porifera: The Development and Current Status of the Field. In: Scheuer PJ, editor. Marine Natural Products: Chemical and Biological Perspectives. Vol. 5. Academic Press; 1983. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]; b) Faulkner DJ. Nat Prod Rep. 1998:113. doi: 10.1039/a815113y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Faulkner DJ. Nat Prod Rep. 1997:259. and previous reports in this series. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abou-Shoer MI, Shaala LA, Youssef DTA, Badr JM, Habib AAM. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1464–1467. doi: 10.1021/np800142n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunasekera SP, Cross SS. J Nat Prod. 1992;55:509–512. doi: 10.1021/np50082a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Agemi K, Shigemori H, Ishibashi M, Sasaki T, Mikami Y. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:6617–6622. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross SA, Weete JD, Schinazi RF, Wirtz SS, Tharnish P, Scheuer PJ, Hamann MT. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:501–503. doi: 10.1021/np980414u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang JH, van Soest RWM, Fusetani N, Matsunaga S. J Org Chem. 2007;72:1211–1217. doi: 10.1021/jo062010+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thironet I, Daloze D, Braekman JC, Willemsen P. Nat Prod Lett. 1998;12:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura H, Wu H, Kobayashi J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:4517–4520. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCulloch MWB, Coombs GS, Banerjee N, Bugni TS, Cannon KM, Harper MK, Veltri CA, Virshup DM, Ireland CM. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:2189–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mierzwa R, King A, Conover MA, Tozzi S, Puar MS, Patel M, Covan SJ. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:175–177. doi: 10.1021/np50103a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholas GM, Newton GL, Fahey RC, Bewley CA. Org Lett. 2001;3:1543–1545. doi: 10.1021/ol015845+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan MS, Carroll AR, Fechner GA, Boyle A, Simpson M, Addepalli R, Avery VM, Hooper JNA, Cheung T, Chen H, Quinn RJ. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1066–1067. doi: 10.1021/np0706623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Fujiwara T, Hwang J-H, Kanamoto A, Nagai H, Takagi M, Kauzo S-y. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2009;62:393–395. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shinde PB, Lee YM, Dang HT, Hong J, Lee C-O, Jung JH. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:6414–6418. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kobayashi J, Honma K, Sasaki T, Tsuda M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1995;43:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Murakata M, Yamada K, Hoshino O. Heterocycles. 1998;47:921–931. [Google Scholar]; b) Murakata M, Yamada K, Hoshino O. Chem Commun. 1994:443–444. [Google Scholar]; c) Kacan M, Koyuncu D, McKillop A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1993:1771–1776. [Google Scholar]; d) Noda H, Niwa M, Yamamura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3247–3248. [Google Scholar]; e) Forrester AR, Thomson RH, Woo SO. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1975:2340–2348. [Google Scholar]; f) Forrester AR, Thomson RH, Woo SO. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1975:2348–2353. [Google Scholar]; g) Okamoto KT, Clardy J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4969–4972. [Google Scholar]; h) Forrester AR, Thomson RH, Woo S-O. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1978:66–73. [Google Scholar]; i) Murakata M, Masafumi T, Hoshino O. J Org Chem. 1997;62:4428–4433. doi: 10.1021/jo970082i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Nishiyama S, Yamamura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3351–3352. [Google Scholar]; b) Nishiyama S, Yamamura S. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1985;58:3453–3456. [Google Scholar]; c) Ogamino T, Nishiyama S. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:9419–9423. [Google Scholar]; d) Ogamino T, Ishikawa Y, Nishiyama S. Heterocycles. 2003;61:73–78. [Google Scholar]; e) Shearman JW, Myers RM, Brentonb JD, Ley SV. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:62–65. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00636j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Boehlow TR, Harburn JJ, Spilling CD. J Org Chem. 2001;66:3111–3118. doi: 10.1021/jo010015v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Togo H, Nogami G, Yokoyama M. Synlett. 1998:534–536. [Google Scholar]; h) Ley SV, Thomas AW, Finch H. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1999:669–671. [Google Scholar]; i) Harburn JJ, Rath NP, Spilling CD. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6398–6403. doi: 10.1021/jo050846r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Murakata M, Yamada K, Hoshino O. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:14713–14722. [Google Scholar]; k) Wasserman HH, Wang J. J Org Chem. 1998;63:5581–5586. [Google Scholar]; l) Hentschel F, Lindel T. Synthesis. 2010:0181–0204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Xu J, Wang J, Ellis ED, Hamme AT., II Synthesis. 2006:3815–3818. [Google Scholar]; b) Ellis ED, Xu J, Valente EJ, Hamme AT., II Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5516–5519. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.07.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Shrout DP, Lightner DA. Synthesis. 1990:1062–1065. [Google Scholar]; b) Gu Z, Zakarian A. Org Lett. 2010;12:4224–4227. doi: 10.1021/ol101523z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Takahashi K, Tanaka T, Suzuki T, Hirama M. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:1327–1340. [Google Scholar]; b) Chen BC, Weismiller MC, Davis FA, Boschelli D, Empfield JR, Smith AB., III Tetrahedron. 1991;47:173–182. [Google Scholar]; c) Demir AS, Sesenoglu O. Org Lett. 2002;4:2021–2023. doi: 10.1021/ol025847+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Nelson PH, Nelson JT. Synthesis. 1992:1287–1291. [Google Scholar]; e) Mphahlele MJ, Modro TA. J Org Chem. 1995;60:8236–8240. [Google Scholar]; f) Adam W, Lazarus M, Saha-Möller CR, Schreier P. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:837–845. [Google Scholar]; g) Patel RN. Curr Org Chem. 2006;10:1289–1321. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Henderson LC, Loughlin WA, Jenkins ID, Healy PC, Campitelli MR. J Org Chem. 2006;71:2384–2388. doi: 10.1021/jo052485l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Majetich G, Zhang Y, Tian X, Britton JE, Li Y, Phillips R. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:10129–10146. [Google Scholar]; c) Wińska K, Grudniewska A, Chojnacka A, Białońska A, Wawrzeńczyk C. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:670–678. [Google Scholar]; d) Patel RN. Curr Org Chem. 2006;10:1289–1321. [Google Scholar]; e) Clerici A, Pastori N, Porta O. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolaou KC, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G, Mathison CJN. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8872–8888. doi: 10.1021/ja0509984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Encarnación RD, Sandoval E, Mamstrøm J, Christophersen C. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:874–875. doi: 10.1021/np990489d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Konig GM, Wright AD. Heterocycles. 1993;36:1351–1359. [Google Scholar]; c) Kijjoa A, Watanadilok R, Sonchaeng P, Silva AMS, Eaton G, Herz W, Naturforsch Z. C J Biosci. 2001;56:1116–1119. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-11-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Bardhan S, Schmitt DC, Porco JA., Jr Org Lett. 2006;8:927–930. doi: 10.1021/ol053115m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Nicolaou KC, Vassilikogiannakis G, Montagnon T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:3276–3281. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3276::AID-ANIE3276>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nicolaou KC, Montagnon T, Vassilikogiannakis G. Chem Commun. 2002:2478–2479. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3276::AID-ANIE3276>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CCDC 967652 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for compound 10.

- 24.Prepared using literature procedure. Gensler WJ, Johnson FA, Sloan DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:6074–6081.

- 25.Nakata T, Tanaka T, Oishi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4723–4726. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.