Abstract

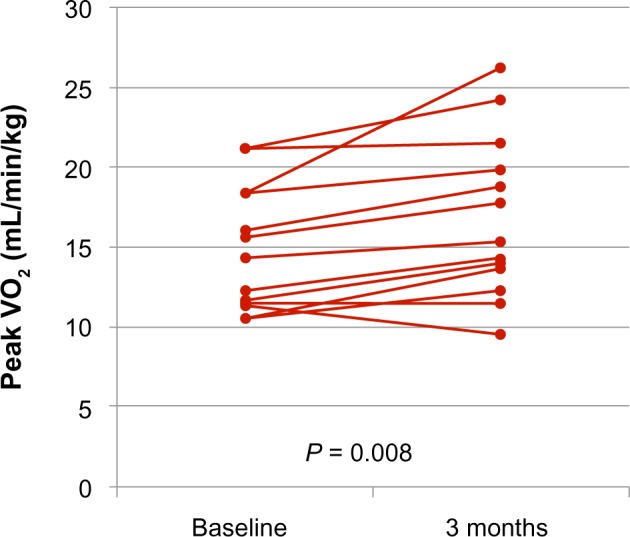

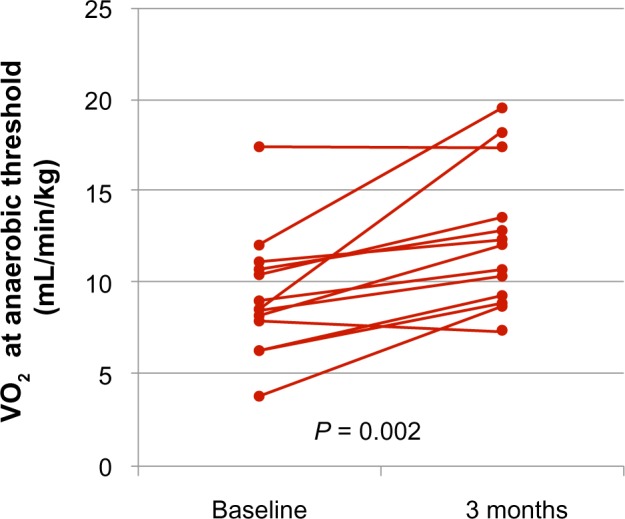

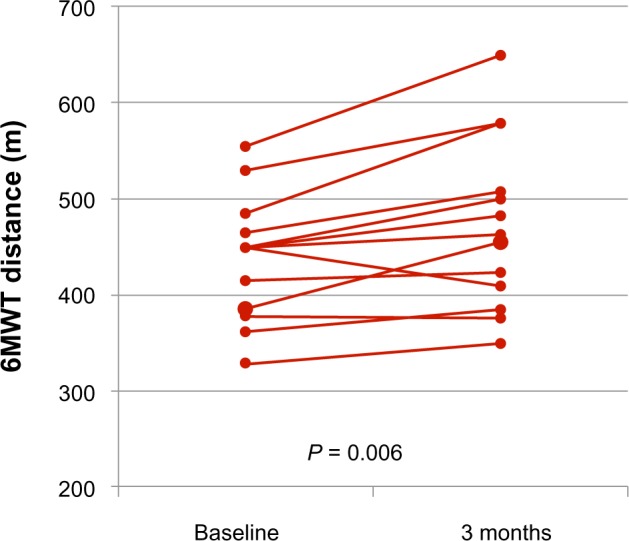

Amino acids (AAs) availability is reduced in patients with heart failure (HF) leading to abnormalities in cardiac and skeletal muscle metabolism, and eventually to a reduction in functional capacity and quality of life. In this study, we investigate the effects of oral supplementation with essential and semi-essential AAs for three months in patients with stable chronic HF. The primary endpoints were the effects of AA’s supplementation on exercise tolerance (evaluated by cardiopulmonary stress test and six minutes walking test (6MWT)), whether the secondary endpoints were change in quality of life (evaluated by Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire—MLHFQ) and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels. We enrolled 13 patients with chronic stable HF on optimal therapy, symptomatic in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II/III, with an ejection fraction (EF) <45%. The mean age was 59 ± 14 years, and 11 (84.6%) patients were male. After three months, peak VO2 (baseline 14.8 ± 3.9 mL/minute/kg vs follow-up 16.8 ± 5.1 mL/minute/kg; P = 0.008) and VO2 at anaerobic threshold improved significantly (baseline 9.0 ± 3.8 mL/minute/kg vs follow-up 12.4 ± 3.9 mL/minute/kg; P = 0.002), as the 6MWT distance (baseline 439.1 ± 64.3 m vs follow-up 474.2 ± 89.0 m; P = 0.006). However, the quality of life did not change significantly (baseline 21 ± 14 vs follow-up 25 ± 13; P = 0.321). A non-significant trend in the reduction of NT-proBNP levels was observed (baseline 1502 ± 1900 ng/L vs follow-up 1040 ± 1345 ng/L; P = 0.052). AAs treatment resulted safe and was well tolerated by all patients. In our study, AAs supplementation in patients with chronic HF improved exercise tolerance but did not change quality of life.

Keywords: amino acid, heart failure, exercise capacity, nutrition, systolic dysfunction

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is the leading cause of death and hospitalization in industrialized countries, and covers an important part of the health care costs.1–3 In recent years, the introduction of new drugs and the use of devices has reduced mortality rates;4 however, the hospitalization rates continue to increase and the prognosis still remains unsatisfactory with high mortality and readmission rates.5–7 The growing acknowledge regarding metabolic abnormalities, hypercatabolic status, and cachexia in HF and their impact on outcomes have contributed to consider HF as a cardiac and whole body metabolic disease, which may be the final pathway of the hemodynamic abnormalities and the neurohormonal and inflammatory activation.8 Several macro and micronutrients deficiencies have been recognized in HF and lead to a disruption in energy as well as in anabolic metabolism. Among micronutrients, amino acids (AAs) act in both these metabolic pathways as intermediary for energy production and transfer and as main constituents of proteins.9 The aim of our study was to evaluate the effects of the administration of a mixture of 11 AAs on functional capacity expressed by the improvement in cardiopulmonary stress test parameters and six minutes walking test (6MWT) distance. The secondary endpoints were to evaluate the effects on quality of life and NT-proBNP levels in a population of ambulatory patients with chronic HF.

Methods

Patients

We recruited 13 consecutive patients with stable chronic HF because of dilated cardiomyopathy without coronary disease. All patients were symptomatic for HF for ≥6 months in NYHA class II or III, with an ejection fraction (EF) <45% by echocardiography or radionuclide ventriculography (RVG), and able to perform a cardiopulmonary exercise test with a peak VO2 ≥10 mL/kg/minute. Patients were on optimal medical therapy, treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACE) or angiotensin-receptor blocker and beta-blockers at a stable dose for at least four weeks before entering in the study. Patients were excluded if they had ischemic-dilated cardiomyopathy, symptoms of myocardial ischemia, acute coronary syndromes, or a coronary revascularization procedure in the previous three months; implantation of a cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device in the prior six months or likely to receive implantation in the next three months; history of severe valvular disease (with the exception of functional mitral regurgitation); congenital heart disease, acute myocarditis, and hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy; cerebrovascular events or major surgery in the previous six months; and any concomitant disease that might adversely impair the exercise performance or the prognosis of the patient. The investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study received ethical approval from the Department of Cardiology, University of Brescia, and all patients gave their written, informed consent to participate.

Study protocol

A prospective, open study evaluated the efficacy of the administration of a mixture of essential and semi-essential AAs in patients with stable chronic HF. Patients were evaluated at baseline and after a three months follow-up. Each patient underwent clinical assessment, maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test, 6MWT, transthoracic echocardiogram, RVG or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) before initiation of AAs administration and after three months. Each patient followed habitual daily diet. Cardiopulmonary stress test was performed with a cycloergometer with expiratory gas exchange and ECG monitoring, starting with a workload of 20 W with increments of 10 W/minute. All patients performed two preliminary cardiopulmonary tests before the baseline evaluation to be familiar with the procedure with a variability less than 10% in peak VO2 between the screening tests. A maximal exercise was defined as reaching a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) ≥1.10. Peak VO2 was measured at the maximal exercise as the average value in the last 30 seconds of exercise.

Patients received for three months a mixture of essential and semi-essential AAs (L-leucine, L-lysine, L-isoleucine, L-valine, L-threonine, L-cystine, L-hystidine, L-phenylalanine, L-methionine, L-tyrosine, L-tryptophan; the composition is outlined in Table 1), thiamine, and pyridoxine (Aminotrofic®, Professional Dietistic, Milan, Italy), at the dose of 4 g twice a day, diluted with water, at 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of Aminotrofic®.

| AMINO ACID | |

|---|---|

| Total amino acids | 4 g |

| L-Leucine | 1250 mg |

| L-Lysine | 650 mg |

| L-Isoleucine | 625 mg |

| L-Valine | 625 mg |

| L-Threonine | 350 mg |

| L-Cystine | 150 mg |

| L-Hystidine | 150 mg |

| L-Phenylalanine | 100 mg |

| L-Methionine | 50 mg |

| L-Tyrosine | 30 mg |

| L-Triptophan | 20 mg |

The primary endpoint was to evaluate the effects of AAs supplementation on exercise tolerance at cardiopulmonary stress test and 6MWT. The secondary endpoints were to evaluate the effects on quality of life and NT-proBNP levels.

Echocardiographic analysis

Echocardiography examinations were performed by experienced operators in accordance with the recommendations of the European Society of echocardiography10 using a Vivid Seven (GE Healthcare, UK) system operating at 3.4 MHz. Doppler tracings and two-dimensional images were obtained from parasternal long- and short-axes, apical, and subcostal views. Two-dimensional guided M-mode measurements of left ventricle’s (LV’s) internal dimensions, and septum and posterior wall thicknesses were made at the LV minor axis. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured using Simpson’s biplane method.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as percentages, normally distributed continuous data as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed variables as median and interquartile range. Comparisons were made with paired Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables as appropriate. For the statistical analysis, we used the SPSS version 19.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a two-sided P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Baseline characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 2. We enrolled 13 patients, and all patients reached the end of the study after a follow-up of three months. The mean age was 59 ± 14 years, and 11 (84.6%) patients were male. All patients were treated with ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs and beta-blockers at baseline, and the treatment did not change significantly during the follow-up period. Renal function was normal or mildly reduced at baseline (serum creatinine 1.0 ± 0.3 mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate 88.8 ± 27.6 mL/minute/m2), and NT-proBNP levels were elevated 1502 ± 1900 ng/L in agreement with other studies in ambulatory patients with HF.11 Echocardiographic and functional capacity data at baseline and follow-up are outlined in Table 3. All patients had a moderate to severe LV dysfunction with an EF 29.0 ± 7.9% by echocardiography and dilated LV demonstrated with an end diastolic diameter (EDD) 7.3 ± 1.0 mm and end diastolic volume index (EDVI) 107.2 ± 34.6 mL. Data regarding LV function evaluated by echocardiography were consistent with the equilibrium RVG or cardiac MRI measurements, which estimated an EF of 30.1 ± 9.2% at baseline. The functional capacity, assessed with cardiopulmonary stress test, was reduced at baseline with a peak VO2 of 14.8 ± 3.9 mL/minute/kg. During the treatment period, no adverse effects have been documented by either relevant medical history or laboratory values’ abnormalities. No patient died or has been rehospitalized during the study.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics.

| BASELINE (n = 13) | FOLLOW-UP (n = 13) | P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age—yr | 59 ± 14 | ||

| Men—no. (%) | 11 (84.6) | ||

| SBP—mmHg | 121 ± 14 | 116 ± 12 | 0.172 |

| DBP—mmHg | 75 ± 9 | 71 ± 9 | 0.160 |

| Heart rate—bpm | 69 ± 13 | 67 ± 11 | 0. 518 |

| BMI—kg/m2 | 25.7 ± 3.2 | 25.4 ± 2.8 | 0.316 |

| Comorbidities—n (%) | |||

| DM | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Hypertension | 6 (46.2) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 7 (53.8) | ||

| Smoker | 3 (23.1) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (23.1) | ||

| COPD | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Laboratory values | |||

| Creatinine—mg/dl | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.146 |

| eGFR—ml/min/m2 | 88.8 ± 27.6 | 84.2 ± 28.1 | 0.228 |

| Haemoglobin—g/dl | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 13.1 ± 4.1 | 0.253 |

| Cholesterol—mg/dl | 182 ± 34 | 165 ± 36 | 0.061 |

| Triglycerides—mg/dl | 115 ± 63 | 97 ± 33 | 0.232 |

| CRP—u/l | 9.1 ± 24.9 | 1.6 ± 1.6 | 0.302 |

| NT-proBNP – ng/l | 1502 ± 1900 | 1040 ± 1345 | 0.052 |

| Medications—n (%) | |||

| Beta-blocker | 13 (100) | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 13 (100) | ||

| Aldosterone antagonist | 9 (69.2) | ||

| Loop diuretic | 10 (76.9) | ||

| Statin | 5 (38.5) | ||

Table 3.

Echocardiographic and exercise capacity data.

| BASELINE (n = 13) | FOLLOW-UP (n = 13) | P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic data | |||

| EDD—mm | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 0.212 |

| EDVI—ml | 107.2 ± 34.6 | 99.2 ± 34.3 | 0.071 |

| IVS—mm | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.528 |

| EF—% | 29.0 ± 7.9 | 30.8 ± 9.1 | 0.095 |

| TR gradient—mmHg | 34.9 ± 14.6 | 30.8 ± 5.7 | 0.202 |

| Mitral regurgitation (moderate to severe) | 6 (46.2) | 5 (38.5) | 0.104 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation (moderate to severe) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.277 |

| EF by equilibrium RVG or MRI | 30.1 ± 9.2 | 31.7 ± 10.1 | 0.304 |

| Cardiopulmonary stress test | |||

| Peak VO2—ml/min/Kg | 14.8 ± 3.9 | 16.8 ± 5.1 | 0.008 |

| VE/VCO2 | 37.1 ± 6.9 | 37.4 ± 7.7 | 0.754 |

| % Peak VO2 | 54.0 ± 10.3 | 61.4 ± 13.7 | 0.061 |

| VO2 at AT- ml/min/Kg | 9.0 ± 3.8 | 12.4 ± 3.9 | 0.002 |

| RER | 1.13 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.31 | 0.281 |

| Workload max—Watt | 100.9 ± 32.4 | 104.8 ± 28.4 | 0.380 |

| 6MWT | 439.1 ± 64.3 | 474.2 ± 89.0 | 0.006 |

| MLHFQ score | 21 ± 14 | 25 ± 13 | 0.321 |

Treatment effects

After three months treatment with AAs supplement, the EF and the other echocardiographic parameters did not change significantly: EF (baseline 29.0 ± 7.9% vs follow-up 30.8 ± 9.1%; P = 0.095) and EDD (baseline 7.3 ± 1.0 mm vs follow-up 7.2 ± 0.9 mm; P = 0.212). A trend in the reduction of EDVI (baseline 107.2 ± 34.6 mL vs follow-up 99.2 ± 34.3 mm; P = 0.071) was observed. Compared with baseline, peak VO2 (baseline 14.8 ± 3.9 mL/minute/kg vs follow-up 16.8 ± 5.1 mL/minute/kg; P = 0.008) and VO2 at anaerobic threshold improved significantly (baseline 9.0 ± 3.8 mL/minute/kg vs follow-up 12.4 ± 3.9 mL/minute/kg; P = 0.002) (Figs. 1 and 2). Also the 6MWT distance increased at three months (baseline 439.1 ± 64.3 m vs follow-up 474.2 ± 89.0 m; P = 0.006) (Fig. 3). The perception of symptoms and quality of life evaluated with the MLHFQ did not change significantly compared with baseline (baseline 21 ± 14 vs follow-up 25 ± 13; P = 0.321). A non-significant trend in the reduction of NT-proBNP levels was observed at follow-up (baseline 1502 ± 1900 ng/L vs follow-up 1040 ± 1345 ng/L; P = 0.052).

Figure 1.

Peak VO2 after three months of administration of AAs.

Figure 2.

VO2 at anaerobic threshold after three months of administration of AAs.

Figure 3.

6MWT distance after three months of administration of AAs.

Discussion

In recent years, many studies focused on the macro- and micronutrient deficiencies in HF and their contribution to the pathophysiology and progression of the cardiac dysfunction that eventually leads to a reduction in exercise tolerance and quality of life. The AAs play a prominent role in this setting.9,12 Patients with HF develop progressively a hypercatabolic state that results in advanced stages in cardiac cachexia.13 These abnormalities in cardiac and whole body metabolism are related to the poor absorption of nutrients by the congested bowel wall; by the activation of local and systemic inflammatory response; by the neurohormonal abnormalities, such as sympathetic and RAAs activation; and by the prevalence of catabolic hormones. The final effect is a gradual release of the AAs stored in the skeletal muscle and their transformation through the liver into glucose that is used as a energy source in the heart and in the other glucose-dependent organs, namely the brain. The continuous release of AAs from the skeletal muscle leads to a progressive loss in muscle bulk and thus a reduction in exercise performance. In patients with HF there is a shift in skeletal muscle fibers’ type from the “red fibers” that are more efficient in energy utilization compared to “white fibers” that are more dependent on the glycolysis. In the failing heart the increase of read fibers promotes the release of lactic acid that contributes to exercise intolerance and early fatigue. Eventually, the patients with HF develop a deficit of AAs that are necessary for the failing heart as a energy source and for protein synthesis, which results in the progression of the disease.14 Thus, in recent years many studies investigated the possible favorable role of AAs supplementation in HF. Almost all those studies have a positive result in terms of increase in exercise tolerance and quality of life, although many of them were conducted with the supplementation of one or few molecules. In the first study, Azuma and colleagues showed that supplementation of taurine in patients with chronic stable HF has favorable effects on symptoms.15,16 Subsequently, several studies have shown that supplementation of a single AA in patients with HF was able to improve the functional capacity. Mancini et al.17 observed in 60 patients affected by stable chronic HF that the supplementation of L-carnitine for six months improved the maximum exercise duration, and Anand et al.18 described 30 patients with HF in whom the supplementation of L-carnitine for one month improved peak VO2 and exercise duration. The major limitation of these early studies is the supplementation of a single type of AA. Furthermore, some AAs act as cofactors in many enzymatic reactions that have a key role in energy production. Most of them are essential AAs, namely AAs that cannot be synthesized and have to be introduced with the diet. However, an increase in protein intake with diet is not enough to counteract the AAs deficit.19 In this view, mixed AAs supplementation should be encouraged. In our study, we treated 13 patients with chronic stable HF, in NYHA class II–III with a mixture of essential and semi-essential AAs supplementation at the dose of 4 g twice a day. After three months of follow-up, exercise tolerance, evaluated as peak VO2, VO2 at anaerobic threshold and 6MWT distance improved. Moreover, we observed a trend in the reduction of EDV and of NT-proBNP levels. AAs treatment resulted well tolerated, without reported side effects or abnormalities in laboratory tests.

Our results are consistent with the previous studies. Aquilani et al.20 randomized in a double-blind fashion 95 patients with stable chronic HF in NYHA class II–III to essential AAs mixture (4 g twice daily) or placebo, and after one month of follow-up, observed a significant improvement in exercise capacity in the treatment with exercise maximal workload (P < 0.01), duration (P < 0.02) and peak VO2 (P < 0.02). Similar results were obtained in another open label, placebo-controlled trial, which enrolled 15 stable chronic HF patients with EF <40%. In the group treated with essential AAs mixture, they observed an improvement in the 6MWT distance.21

In our study, the results of almost all the trials are promising, finding a positive association between mixed AAs supplementation and improvement in functional capacity, and resulted well tolerated and safe. Different from previous studies, we have analyzed a very heterogeneous mixture composed of 11 AAs. Our results encourage a wide range of micronutrient supplementation considering the serious depletion of macro- and micronutrients present in patients with HF.

Our study has some limitations, namely small sample size, the absence of a control group, and the short period of follow-up. Another major limitation is that in our study, we did not evaluate myocardial viability prior to AAs supplementation. This may be a confounding factor as muscle-depletion by itself and a more advanced stage of the disease are associated with a more pronounced exercise intolerance. Another limitation is the lack of plasma assay of a marker of muscle metabolism (eg, lactic acid) that could more accurately confirm the favorable effects of the mixture of AAs on the functional capacity.

In our study, supplementation with essential and semi-essential AAs for three months in patients with stable chronic HF improved exercise tolerance. However, it did not change symptoms’ perception and quality of life and NT-proBNP levels. AAs treatment resulted safe and was well tolerated by all patients. We conclude that AAs supplementation may be a useful non-pharmacologic treatment, associated with conventional therapy, in patients with HF. Larger studies are needed to confirm these data and to investigate the potential benefits of AAs supplementation on the patients’ outcomes.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: CL, VC, MM. Analyzed the data: VC, VL, EV, FQ, RR. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: VC, CL, FG. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: MM, SN. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: CL, VC, VL, EV, FQ, FG, RR, SN, MG, MM. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: MM, CL, VC. Made critical revisions and approved final version: MG, MM. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Thomas E. Vanhecke, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: Essential amminoacids were provided by Aminotrofic Inc, Professional Dietistic, Milan, Italy.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Marco Metra received consulting incomes from Bayer, Novartis, Servier. Mihai Ghoerghiade received consulting incomes Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare AG, CorThera, Cytokinetics, DebioPharm S.A., Errekappa Terapeutici, Glaxo- SmithKline, Ikaria, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Trevena Therapeutics.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Follath F, et al. The EuroHeart Failure survey programme—a survey on the quality of care among patients with heart failure in Europe. Part 1: patient characteristics and diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:442–63. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00823-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullough PA, Philbin EF, Spertus JA, Kaatz S, Sandberg KR. Confirmation of a heart failure epidemic: findings from the Resource Utilization Among Congestive Heart Failure (REACH) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:60–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang J, Mensah GA, Croft JB, Keenan NL. Heart failure-related hospitalization in the U.S., 1979 to 2004. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:428–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed A, Allman RM, Fonarow GC, et al. Incident heart failure hospitalization and subsequent mortality in chronic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. J Card Fail. 2008;14:211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gheorghiade M, Pang PS. Acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:557–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milo-Cotter O, Cotter-Davison B, Lombardi C, Sun H, Bettari L, et al. Neurohormonal activation in acute heart failure: results from VERITAS. Cardiology. 2011;119(2):96–105. doi: 10.1159/000330409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taegtmeyer H, Harinstein ME, Gheorghiade M. More than bricks and mortar: comments on protein and amino acid metabolism in the heart. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:3E–7E. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Januzzi JL, Jr, Rehman SU, Mohammed AA, et al. Use of amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide to guide outpatient therapy of patients with chronic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(18):1881–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ardehali H, Sabbah HN, Burke MA, et al. Targeting myocardial substrate metabolism in heart failure: potential for new therapies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(2):120–9. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Haehling S, Doehner W, Anker SD. Nutrition, metabolism, and the complex pathophysiology of cachexia in chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soukoulis V, Dihu JB, Sole M, et al. Micronutrient deficiencies an unmet need in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Oct 27;54(18):1660–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azuma J, Hasegawa H, Sawamura A, et al. Therapy of congestive heart failure with orally administered taurine. Clin Ther. 1983;5:398–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azuma J, Sawamura A, Awata N, et al. Therapeutic effect of taurine in congestive heart failure: a double-blind crossover trial. Clin Cardiol. 1985;8:276–82. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini M, Rengo F, Lingetti M, Sorrentino GP, Nolfe G. Controlled study on the therapeutic efficacy of propionyl-l-carnitine in patients with congestive heart failure. Arzneimittelforschung. 1992;42:1101–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand I, Chandrashekhan Y, De Giuli F, et al. Acute and chronic effects of propionyl-l-carnitine on the hemodynamics, exercise capacity, and hormones in patients with congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1998;12:291–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1007721917561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aquilani R, Opasich C, Gualco A, et al. Adequate energy-protein intake is not enough to improve nutritional and metabolic status in muscle-depleted patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(11):1127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aquilani R, Viglio S, Iadarola P, et al. Oral amino acid supplements improve exercise capacities in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(suppl):104E–10E. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scognamiglio R, Testa A, Aquilani R, Dioguardi FS, Pasini E. Impairment in walking capacity and myocardial function in the elderly: is there a role for non-pharmacologic therapy with nutritional amino acid supplements? Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(suppl):78E–81E. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]