Abstract

Multi-morbidity, dependency, and frailty were studied simultaneously in a community-living cohort of 4,000 men and women aged 65 years and over to examine the independent and combined effects on four health outcomes (mortality, decline in physical function, depression, and polypharmacy). The influence of socioeconomic status on these relationships is also examined. Mortality data was documented after a mean follow-up period of 9 years, while other health outcomes were documented after 4 years of follow-up. Fifteen percent of the cohort did not have any of these syndromes. Of the remaining participants, nearly one third had multi-morbidity and frailty (pre-frail and frail), while all three syndromes were present in 11 %. All syndromes as well as socioeconomic status were significantly associated with all health outcomes. Mortality was only increased for age, being male, frailty status, and combinations of syndromes that included frailty. Both multi-morbidity and frailtymale was protective. Only a combination of all three syndromes, and age per se, increased the risk of depressive symptoms at 4 years while being male conferred reduced risk. Multi-morbidity, but not frailty status or dependency, and all syndrome combinations that included multi-morbidity were associated with use of ≥ four medications. Decline in homeostatic function with age may thus be quantified and taken into account in prediction of various health outcomes, with a view to prevention, management, formulation of guidelines, service planning, and the conduct of randomized controlled trials of interventions or treatment.

Keywords: Multi-morbidity, Frailty, Dependency, Depression, Mortality, Physical limitation

Introduction

In the past decade, there is an increasing volume of literature on the impact of multi-morbidity, dependency, and frailty on health outcomes (Jarrett et al. 1995; Cigolle et al. 2007; Carriere et al. 2005; Theou et al. 2012; Stineman et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2011; Rozzini et al. 2005; Koroukian 2009; Koroukian et al. 2010; Kadam and Croft 2007; Fortin et al. 2006). Health outcomes commonly include mortality, increasing functional limitation, polypharmacy, psychological well-being, and service utilization. Dependency is frequently represented by limitations in physical activity and/or measures of self-care such as basic and instrumental activities of daily living. Multi-morbidity is defined as coexistence of more than one chronic medical condition, whether it be physical or mental. Frailty represents a state of multisystem impairments resulting from age-related physiological changes consequent to impaired homeostasis occurring in the continuum from normal ageing to a final state of disability and death. Definitions range from the multi-deficits frailty index (Rockwood and Mitnitski 2007) to the phenotypic definition proposed by Fried (Fried et al. 2001) to practical bedside measures such as the FRAIL score (Abellan van Kan et al. 2008) and the Canadian Study of Health and Ageing clinical frailty scale (Rockwood et al. 2005). Although the definitions of dependency, multi-morbidity, and frailty are distinct, they are overlapping syndromes (Fried et al. 2004), and commonly coexist among older populations. Better understanding of the interactive nature of these syndromes and how they affect health outcomes would guide management strategies in terms of prevention and intervention.

Different syndromes may have variable contribution to different outcomes (Byles et al. 2005; Perruccio et al. 2007; Valderas et al. 2009; Huntley et al. 2012). Furthermore, socioeconomic factors may modulate this relationship (Lucchetti et al. 2009; Gobbens et al. 2010). Few studies examined these syndromes simultaneously in the same population to determine the extent of overlap, their variable independent and/or cumulative impact on health outcomes, and how this relationship may be affected by socioeconomic status (SES). These questions are addressed by a study of a community-living cohort of 4,000 men and women aged 65 years and over to examine the independent and combined effects of multi-morbidity, dependency, and frailty on four health outcomes (mortality, decline in physical function, depression, and polypharmacy). The influence of socioeconomic status on these relationships is also examined.

Subjects and methods

Between 2001 and 2003, 4,000 men and women aged 65 years and over living in the community responded to recruitment notices in community centers for the elderly and housing estates for a health check carried out in the School of Public Health of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The target was a stratified sample so that approximately 33 % would be in each of these age groups: 65–69, 70–74, and 75+. Exclusion criteria included inability to walk independently, a history of bilateral hip replacements, mental incapacity in giving informed consent, and presence of medical conditions that in the judgment of study doctors would reduce the chance of survival during the next 4 years such as cancer, end stage renal, heart, or chronic lung diseases were excluded. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, which requires informed consent to be obtained.

A team administered a questionnaire and measurements containing the following items: the number of prescription medications; any difficulties with performing three items of instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (preparing own meals, doing housework such as cleaning floors or windows, and doing own shopping for groceries or clothes); any difficulties with exertional physical activities such as climbing up ten steps without resting or moving furniture; the presence or absence of disease was based on subjects' report of diagnosis by their doctors; depressive symptoms assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al. 1983) with a score ≥8 representing depressive symptoms, validated in elderly Chinese subjects (Lee et al. 1993); and equivalent items used for classification of frailty status using the Cardiovascular Health Study score (Fried et al. 2001): having no energy, grip strength measurement falling into the first quartile, walking speed measurement in the fourth quartile (i.e., slowest), Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) score (Washburn et al. 1993) in the lowest quartile, and body mass index <18.5 kg/m2. The maximum score of 5 represents the greatest degree of frailty. A score of 1–2 represents a pre-frail state, while a score of ≥3 represents frailty.

Walking speed was recorded by measuring the time taken to walk 6 m. Body weight was measured with subjects wearing a light gown, by the Physician Balance Beam Scale (Healthometer, Illinois, USA). Height was measured by the Holtain Harpenden standiometer (Holtain Ltd, Crosswell, UK). Body mass index was calculated by dividing the weight in kilogram by the square of the height in meters. Grip strength was measured using a dynamometer JAMAR hand dynamometer 5030JI, Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, IL. If there was pain, arthritis, or previous surgery on that hand, grip strength was not tested in that hand. Research staff first demonstrated the procedure, followed by the participant practicing the movement with the arm bent at the elbow resting on the table. The average for four readings of right and left sides were used. Self-rated SES was assessed by asking participants to place a mark on a picture of an upright ladder with ten rungs, with the top rung representing people who have the most money, the most education, and the most respected jobs, and the bottom rung representing people at the other extreme (SES ladder). This is a subjective measure of social status developed by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health, and has been associated with key health outcomes in various population surveys of different cultural and ethnic groups (Adler et al. 2000), and had been applied in the Hong Kong population to examine gender differences in socioeconomic status (Woo et al. 2008).

Multi-morbidity was defined as having two or more chronic diseases. Dependency was dichotomized into two groups: those with difficulty in performing two to three instrumental activities of daily living (score 2–3) versus those with no difficulty or only difficulty with one IADL item. Frailty status was separated into two groups: “robust” (score 0) and “frail” (score ≥1). Participants were categorized into seven mutually exclusive groups for analyses: multi-morbidity alone (A), dependency alone (B), frailty alone (C), A + B, A + C, B + C, and finally all three syndromes combined (A + B + C).

Outcome measures at follow-up

All participants were followed up for 4 years and returned for assessment during the fifth year. Mortality was documented through a search of the Hong Kong Death Registry. The cutoff date for determining mortality was 31 March 2012. Physical limitation at follow-up was assessed using the following two questions: do you have any difficulty in climbing stairs (possible answers: no, a little, a lot); do you have any difficulty in carrying out the following household activities such as moving chairs or tables (possible answers: no, a little, a lot). Participants were categorized as having physical limitation if the answer to either question was “a little” or “a lot,” while those who answered “no” to both questions were categorized as having no physical limitation. Increasing physical limitation was defined as progression from those without limitation at baseline to having limitation at follow-up. The GDS was repeated and those with GDS ≥8 but with GDS <8 at baseline were classified as developing depression. The number of drugs used was documented. Polypharmacy was defined as taking four or more drugs at follow-up (the crude prevalence was used).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Multi-morbidity, dependency, frailty and SES were analyzed with different health outcomes by chi square tests. To assess the risk prediction ability of SES for different outcomes in addition to other risk factors, two models (M1 and M2) were compared. M1 included sex, age, and combination of multi-morbidity, dependency, and frailty. M2 contained covariates in M1 and SES. Death, increase in physical limitation after 4 years, and newly developed depressive symptoms were analyzed by Cox proportional hazard regression. The area under the curve (AUC) estimated by Harrell C statistic was used to measure the concordance of predictive values with actual outcomes. Drug use (≥4) at 4 years was analyzed by logistic regression. The AUC was estimated by C statistic. AUCs were compared using Wilcoxon tests between them. Reclassification improvement was calculated using the net reclassification improvement (NRI) index and the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) index (Lluis-Ganella et al. 2012; Cook and Ridker 2009) The NRI distinguishes movements in correct direction (up for cases and down for non-cases). Ideally, the predicted probabilities would move higher (up a category) for cases and lower (down a category) for non-cases. The NRI is defined as:

where Pr stands for probability and RI stands for relative improvement.

The IDI is the difference in Yates slopes between two models, which is the mean difference in predicted probabilities between cases and non-cases. The IDI is defined as:

where P is the predicted probability. The terms in parentheses are the Yates slopes for the two models.

For the assessment of reclassification improvement, we defined four risk categories (low, intermediate–low, intermediate–high, and high) by using 0–4.9, 5–9.9, 10–19.9, and 20 % or above. All statistical tests were two-sided. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

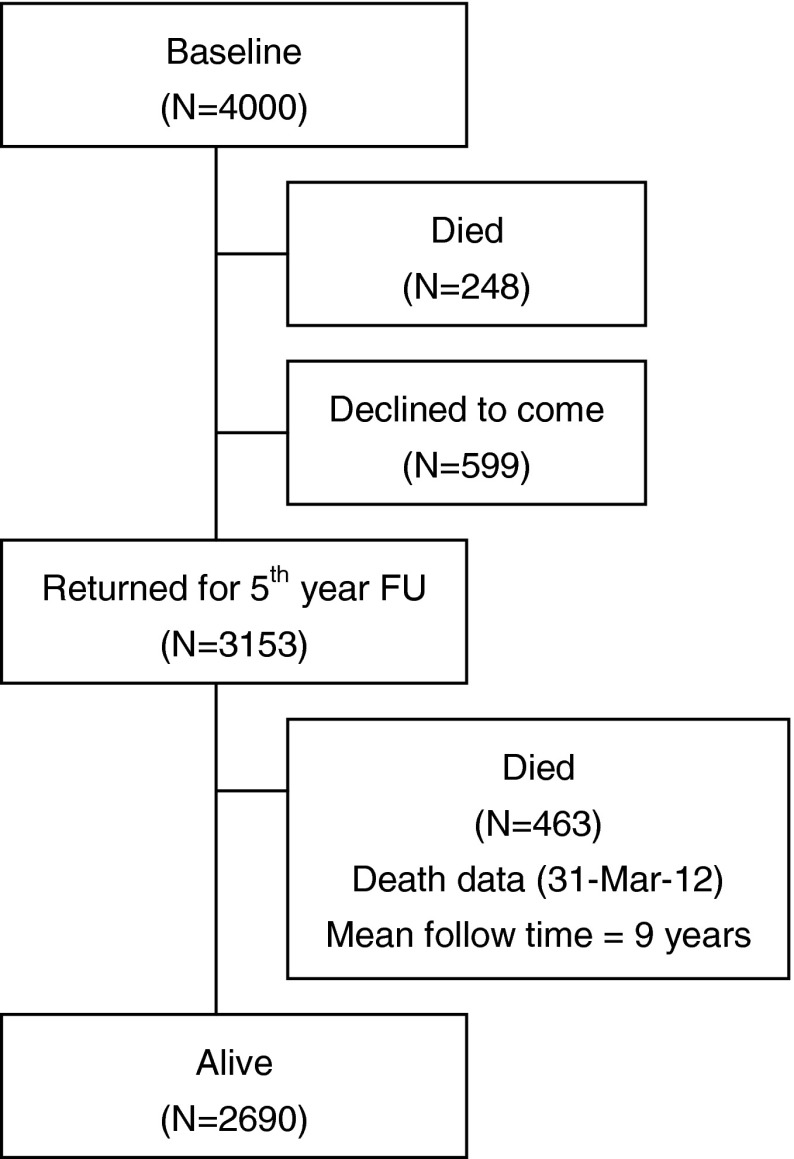

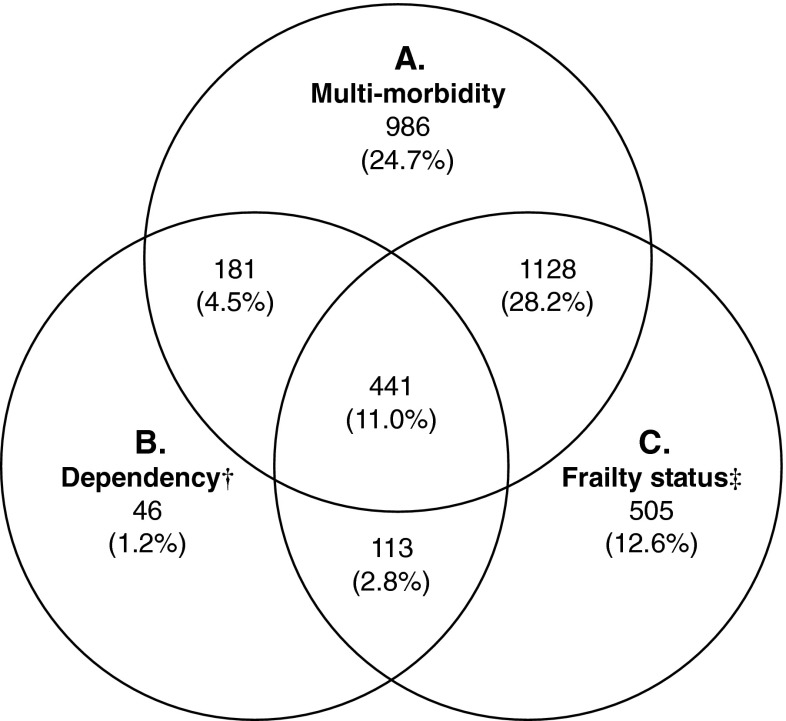

Of 4,000 participants, 248 had died by the fifth year of follow-up, while 599 declined to return (Fig. 1). Those who did not return were older, were more dependent, and had higher frailty status. Up till March 2102, a further 463 people had died at the end of a mean follow-up period of 9 years. The frequency of each of the three states at baseline is shown in Fig. 2, showing that these syndromes may occur independent of each other, and also have varying extent of overlap. Fifteen percent of the cohort did not have any of these syndromes. Of the remaining participants, nearly one third had multi-morbidity and frailty (pre-frail and frail), while all three syndromes were present in 11 %. The prevalence for each of the five frailty domains was having no energy (6.2 %), grip strength falling into the first quartile (23.7 %), walking speed measurement in the slowest quartile (24.6 %), PASE score in the lowest quartile (25 %), and body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 (5.4 %). All syndromes as well as socioeconomic status were significantly related with all health outcomes examined, using Chi square test not adjusted for multiplicity (Table 1). The relationship between syndromes and health outcomes (mortality after a mean of 9 years, increase in physical limitation, depression, and number of drugs at follow-up after 4 years) is shown in Table 2. For mortality, risk is increased only for combinations of syndromes that included frailty, as well as older age and being male, the AUC being 0.723. Being in the lowest third of the SES ladder also increased mortality, but addition of SES, only marginally increased the prediction accuracy by 0.3 %, although the increase is statistically significant (IDI = 0.003, p < 0.05). This suggests that while SES independently predicts mortality, the magnitude of the impact is small in the presence of other factors in the model.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Fig. 2.

Frequency (in percent) of three syndromes, n = 4,000. Six hundred (15.0 %) subjects did not have any of the three syndromes. Dagger, any difficulty with meals, housework, or shopping; double dagger, pre-frail/frail

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in relation to health outcomes at 4 and 9 years

| Variable | Freq (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality at 9 years | Increase in physical limitation after 4 years | Depression at 4 yearsa | Drug use (≥4) at 4 years | |||||

| No (n = 3,289) | Yes (n = 711) | No (n = 2,142) | Yes (n = 1,011) | No (n = 2,763) | Yes (n = 124) | No (n = 2,634) | Yes (n = 519) | |

| A. Multi-morbidity | p b = 0.0010 | p b < 0.0001 | p b = 0.0296 | p b < 0.0001 | ||||

| 0–1 | 1,076 (85.1 %) | 188 (14.9 %) | 785 (75.6 %) | 254 (24.5 %) | 944 (96.4 %) | 35 (3.6 %) | 994 (95.7 %) | 45 (4.3 %) |

| 2–3 | 1,485 (81.8 %) | 330 (18.2 %) | 931 (66.0 %) | 479 (34.0 %) | 1,244 (96.1 %) | 51 (3.9 %) | 1,190 (84.4 %) | 220 (15.6 %) |

| ≥ 4 | 728 (79.0 %) | 193 (21.0 %) | 426 (60.5 %) | 278 (39.5 %) | 575 (93.8 %) | 38 (6.2 %) | 450 (63.9 %) | 254 (36.1 %) |

| B. Dependencyc | p b < 0.0001 | p b < 0.0001 | p b = 0.0003 | p b = 0.0037 | ||||

| 0 | 2,688 (83.5 %) | 531 (16.5 %) | 1,818 (69.9 %) | 782 (30.1 %) | 2,317 (96.2 %) | 91 (3.8 %) | 2,198 (84.5 %) | 402 (15.5 %) |

| 1 | 504 (77.2 %) | 149 (22.8 %) | 273 (57.7 %) | 200 (42.3 %) | 394 (94.0 %) | 25 (6.0 %) | 375 (79.3 %) | 98 (20.7 %) |

| 2–3 | 97 (75.8 %) | 31 (24.2 %) | 51 (63.8 %) | 29 (36.3 %) | 52 (86.7 %) | 8 (13.3 %) | 61 (76.3 %) | 19 (23.8 %) |

| C. Frailty status | p b < 0.0001 | p b < 0.0001 | p b = 0.0079 | p b = 0.0002 | ||||

| Robust | 1,593 (87.9 %) | 220 (12.1 %) | 1152 (74.5 %) | 394 (25.5 %) | 1,410 (96.8 %) | 46 (3.2 %) | 1,334 (86.3 %) | 212 (13.7 %) |

| Pre-frail | 1,522 (79.5 %) | 393 (20.5 %) | 921 (63.0 %) | 542 (37.1 %) | 1,241 (94.7 %) | 70 (5.3 %) | 1,187 (81.1 %) | 276 (18.9 %) |

| Frail | 174 (64.0 %) | 98 (36.0 %) | 69 (47.9 %) | 75 (52.1 %) | 112 (93.3 %) | 8 (6.7 %) | 113 (78.5 %) | 31 (21.5 %) |

| SES ladderd | p b = 0.0002 | p b = 0.0384 | p b < 0.0001 | p b = 0.7036 | ||||

| 6–10 (high) | 774 (83.7 %) | 151 (16.3 %) | 536 (72.2 %) | 206 (27.8 %) | 704 (98.1 %) | 14 (2.0 %) | 617 (83.2 %) | 125 (16.9 %) |

| 4–5 | 1,448 (84.4 %) | 267 (15.6 %) | 935 (67.5 %) | 451 (32.5 %) | 1,257 (96.3 %) | 48 (3.7 %) | 1,163 (83.9 %) | 223 (16.1 %) |

| 1–3 (low) | 880 (78.6 %) | 240 (21.4 %) | 576 (66.9 %) | 285 (33.1 %) | 677 (93.5 %) | 47 (6.5 %) | 711 (82.6 %) | 150 (17.4 %) |

aDepression at baseline is excluded

b p value of chi square test between development of adverse outcome or no adverse outcome

cDependency is defined by difficulty with meals, housework, or shopping

dSES, socioeconomic status as represented by the Hong Kong ladder, a self-rated scale from 1 to 10, with lower rungs of the ladder representing lower SES status

Table 2.

Prediction models of health outcomes

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | Odds ratio (95 % CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality at 9 years | Increase in physical limitation after 4 years | Depression at 4 years (depressed at baseline is excluded) | Drug use (≥4) at 4 years | |||||

| M1 | M2 | M1 | M2 | M1 | M2 | M1 | M2 | |

| Syndromesa | ||||||||

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A. Multi-morbidityb alone | 1.20 (0.89, 1.60) | 1.20 (0.89, 1.62) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.78) | 1.46 (1.15, 1.86) | 1.09 (0.56, 2.11) | 1.23 (0.59, 2.55) | 5.72 (3.53, 9.26) | 5.58 (3.44, 9.05) |

| B. Dependencyc alone | 1.22 (0.44, 3.35) | 1.65 (0.60, 4.56) | 0.75 (0.35, 1.62) | 0.80 (0.33, 1.98) | – | – | 0.76 (0.10, 5.85) | 0.92 (0.12, 7.13) |

| C. Frailty (CHS)d alone | 1.14 (0.83, 1.58) | 1.16 (0.83, 1.61) | 1.32 (1.01, 1.73) | 1.33 (1.01, 1.76) | 1.43 (0.69, 2.96) | 1.74 (0.79, 3.83) | 1.36 (0.72, 2.56) | 1.30 (0.68, 2.48) |

| A + B | 0.78 (0.43, 1.38) | 0.90 (0.50, 1.60) | 1.61 (1.16, 2.25) | 1.59 (1.11, 2.27) | 1.74 (0.72, 4.20) | 2.30 (0.91, 5.80) | 11.07 (6.21, 19.74) | 12.01 (6.69, 21.56) |

| A + C | 1.55 (1.18, 2.04) | 1.55 (1.17, 2.06) | 1.86 (1.48, 2.34) | 1.89 (1.50, 2.39) | 1.55 (0.83, 2.90) | 1.78 (0.89, 3.57) | 9.17 (5.68, 14.79) | 8.95 (5.54, 14.46) |

| B + C | 2.42 (1.57, 3.73) | 2.21 (1.37, 3.56) | 2.22 (1.51, 3.28) | 2.27 (1.50, 3.44) | 2.32 (0.82, 6.52) | 2.26 (0.62, 8.23) | 1.72 (0.57, 5.19) | 2.00 (0.66, 6.08) |

| A + B + C | 2.43 (1.78, 3.30) | 2.45 (1.78, 3.37) | 1.85 (1.41, 2.41) | 1.79 (1.35, 2.37) | 2.41 (1.19, 4.90) | 3.11 (1.43, 6.76) | 9.78 (5.72, 16.72) | 9.97 (5.79, 17.16) |

| Male | 2.37 (2.02, 2.80) | 2.35 (1.98, 2.79) | 0.62 (0.55, 0.71) | 0.62 (0.54, 0.70) | 0.64 (0.44, 0.93) | 0.65 (0.44, 0.97) | 1.42 (1.17, 1.74) | 1.38 (1.13, 1.70) |

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.10 (1.09, 1.11) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.11) | 1.01 (1.001, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.001, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) |

| SES ladderd | ||||||||

| 6–10 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 4–5 | 0.94 (0.77, 1.15) | 1.16 (0.98, 1.37) | 1.85 (1.02, 3.36) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.14) | ||||

| 1–3 (low) | 1.22 (0.995, 1.50) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.44) | 3.39 (1.87, 6.18) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.27) | ||||

| AUCH = 0.708 | AUCH = 0.703 | AUCH = 0.615 | AUCH = 0.619 | AUCH = 0.642 | AUCH = 0.670 | AUC = 0.691 | AUC = 0.694 | |

| IDI = 0.003* | IDI = 0.002* | IDI = 0.009* | IDI = 0.0003 | |||||

| NRI = 0.017 | NRI = 0.002 | NRI = 0.135* | NRI = 0.029* | |||||

SES socioeconomic status, M1 model with syndromes, male gender, and age, M2 model with syndromes, male, age, gender, and SES ladder, AUC H area under curve for proportional hazards regression by Harrell C statistic, AUC area under curve for logistic regression, IDI integrated discrimination improvement, comparing M2 with M1, NRI net reclassification improvement, comparing M2 with M1

*p < 0.05

aThere are eight categories with different combinations of A, B, and C, each participant belonging to only one category

bNo. of diseases ≥2

cAny difficulty with meals, housework, or shopping

dCardiovascular Health Scale (CHS) pre-frail/frail

Both multi-morbidity and frailty status alone were associated with increase in physical limitation at 4 years, while significant associations were observed for all combinations of the three syndromes, the strongest associations being seen for combinations including frailty status. Being male reduced the risk of increasing physical limitation by half, while age increased the risk, the AUC being 0.661. Again, low SES ranking was an independent risk factor to increasing physical limitation, although the contribution to the prediction model, though statistically significant, was small (IDI = 0.002). No participant with dependency alone developed depressive symptoms at follow-up. Only a combination of all three syndromes, and age per se, was associated with the occurrence of depressive symptoms at 4 years, while being male conferred reduced risk (M1). Low SES increased the risk of depressive symptoms by over threefold as did the coexistence of all three syndromes in model 2, the AUC being 0.677. Inclusion of SES increased the predictive power by 0.9 % using IDI and 13.5 % using NRI. Multi-morbidity, but not frailty status or dependency, and all syndrome combinations that included multi-morbidity were associated with high ORs for use of ≥ four medications, the values ranging from 5 to 11. Being male, but not increasing age, was associated with increased drug use, the AUC for this prediction model being 0.691. SES, though not independently associated with drug use, contributed slightly to prediction accuracy (2.9 % using NRI)

Discussion

The findings of this study show that multi-morbidity, dependency, and frailty are different constructs that may occur singly or in various combinations in older populations, and that they have variable impact on different health outcomes. Furthermore, while socioeconomic status is known to influence health outcomes (Siegrist and Marmot 2006), socioeconomic status only marginally improves outcome prediction when these syndromes are taken into account. For depression as a health outcome, other than the known influence of gender, it is interesting that coexistence of all three syndromes rather that age is the significant contributor, in addition to socioeconomic status. This observation enlarges on the dimensions of previous studies examining only multi-morbidity and patterns of chronic diseases and quality of life (Kim et al. 2012) and the bi-directional relationship between mental and physical multi-morbidity in the context of deprivation (Mercer et al. 2012). As expected, multi-morbidity is the overriding factor for polypharmacy. The high odds ratio for the combination of multi-morbidity and dependency may be expected in view of the close relationship between disease and disability. The findings are compatible with a study of 1,002 women with impairments in domains of physical functioning aged 65 years and over in the USA, which found that other than presence of specific diseases, multi-morbidity, frailty, and difficulty with instrumental activities of daily living were associated with increase use of prescription drugs (Crentsil et al. 2010). Such profiling would identify patients as potential targets for polypharmacy interventions.

The underlying biological mechanism accounting for the protective effect of the male gender on physical limitation and depressive symptoms is uncertain, Possible mechanisms may include higher prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases such as arthritis and osteoporosis among women (Woo et al. 2004, 2009a) giving rise to greater physical limitation and depression as a result of pain or disability. Lower muscle mass and power in women compared with men may also explain the greater increase in physical limitation in women (Woo et al. 2009b). A higher prevalence of depression among elderly women in Hong Kong has also been documented (Woo et al. 1994).

The findings of this study lend support to the concept that frailty represents a phenomenon of physiological dysregulation with ageing, distinct from disease and disability (Fried et al. 2009). Dysregulation in individual physiological systems such as anemia, inflammation, insulin-like growth factor, and others have been studied, and the cumulative number of systems abnormality undermines homeostatic adaptive capacity resulting in frailty and associated adverse outcomes. Although there is overlap, there are subpopulations with just one of these syndromes. On the other hand, the mathematical model of frailty proposed by Mitnitski and Rockwood uses a cumulative deficit approach, which includes disease and disability, with frailty being represented mathematically as an end product of a balance between environmental damage and time to recovery (Mitnitski et al. 2013). Interestingly, both approaches provide similar predictive power for mortality and incident physical limitation (Woo et al. 2012). The frailty phenotype classification provides a quantitative measure of decline in homeostatic function with age, which represents a separate entity to presence of disease or disability.

The clinical implication of the study is that in care of older patients, these characteristics should form an important part of clinical assessment. Detection of these syndromes through screening may allow formulation of interventional strategies to reduce adverse outcomes. Clinical management of older people should move from the traditional medical model of being disease-centered to being centered on function and frailty. This shift should be taken into account in the formulation of guidelines, service planning, as well as the conduct of randomized controlled trials of interventions or treatment. Depending on the health outcome of interest, difference syndromes may be used in trials either in creating samples stratified according to syndrome classification or as a covariate in analyzing effectiveness of interventions. The inclusion of these syndromes in research settings would be important in improving evidence-based treatments, interventions, and service delivery models in the primary and secondary care settings (Valderas et al. 2009; Huntley et al. 2012; Guthrie et al. 2012). Failure to include frailty status may also explained the discrepancies in results of intervention trials in the community setting for improving outcomes in patients with multi-morbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions (Smith et al. 2012).

There are limitations in this study. The sample is not representative of the general Hong Kong population, in that the education level is higher. Therefore, the baseline prevalence data may not be representative. The follow-up data may be subject to bias towards younger age and those with better frailty status, since these participants were more likely to return. We did not use detailed assessments of physical limitations, and the existence of disease was self-reported and not by doctor's examination. Other health outcome measures such as hospitalization were not included. It is uncertain whether the findings may be extrapolated to the whole population or non-Chinese populations. The strengths of the study include the large sample of community living older people, the inclusion of a large number of variables enabling the three syndromes to be examined simultaneously together with socioeconomic status, and the prospective design. In spite of the limitations, we can conclude that inclusion of frailty status as well as multi-morbidity and dependency are key contributors in different ways to different health outcomes, and ideally should be included in health outcomes research in older people, in intervention trials, management guidelines, and service planning.

References

- Abellan van Kan G, Rolland YM, Morley JE, Vellas B. Frailty: toward a clinical definition. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(2):71–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byles JE, D'Este C, Parkinson L, O'Connell R, Treloar C. Single index of multimorbidity did not predict multiple outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere I, Colvez A, Favier F, Jeandel C, Blain H. Hierarchical components of physical frailty predicted incidence of dependency in a cohort of elderly women. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(11):1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(3):156–164. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook NR, Ridker PM. The use and magnitude of reclassification measures for individual predictors of global cardiovascular risk. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:795–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crentsil V, Ricks MO, Xue QL, Fried LP. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of community-dwelling, disabled older women: factors associated with medication use. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(3):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Lapointe L, Dubois MF, Almirall J. Psychological distress and multimorbidity in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):417–422. doi: 10.1370/afm.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, Ferrucci L, Chaves P, Varadhan R, Guralnik JM, Leng SX, Semba RD, Walston JD, Blaum CS, Bandeen-Roche K. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(10):1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Determinants of frailty. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2010;11(5):356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P, McMurdo ME, Mercer SW. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ. 2012;345:e6341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Salisbury C. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):134–141. doi: 10.1370/afm.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett PG, Rockwood K, Carver D, Stolee P, Cosway S. Illness presentation in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(10):1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430100086010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam UT, Croft PR. Clinical multimorbidity and physical function in older adults: a record and health status linkage study in general practice. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):412–419. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KI, Lee JH, Kim CH. Impaired health-related quality of life in elderly women is associated with multimorbidity: results from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Gend Med. 2012;9(5):309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM. Assessment and interpretation of comorbidity burden in older adults with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(Suppl 2):S275–S278. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM, Xu F, Bakaki PM, Diaz-Insua M, Towe TP, Owusu C. Comorbidities, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes in relation to treatment and survival patterns among elders with colorectal cancer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(3):322–329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HB, Chiu HFK, Kwok WY, Leung CM, Kwong PK, Chung DWS. Chinese elderly and the GDS short form: a preliminary study. Clin Gerontol. 1993;14:37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lluis-Ganella C, Subirana I, Lucas G, Tomas M, Munoz D, Senti M, Salas E, Sala J, Ramos R, Ordovas JM, Marrugat J, Elosua R. Assessment of the value of a genetic risk score in improving the estimation of coronary risk. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222(2):456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti M, Corsonello A, Fabbietti P, Greco C, Mazzei B, Pranno L, Lattanzio F. Relationship between socio-economic features and health status in elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(Suppl 1):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HM, Tang WH, Woo J. Predictors of in-hospital mortality of older patients admitted for community-acquired pneumonia. Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):736–741. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. BMJ. 2012;345:e5559. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitnitski A, Song X, Rockwood K. Assessing biological aging: the origin of deficit accumulation. Biogerontology. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10522-013-9446-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perruccio AV, Power JD, Badley EM. The relative impact of 13 chronic conditions across three different outcomes. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2007;61(12):1056–1061. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.047308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2005;173(5):489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozzini R, Sabatini T, Trabucchi M. Functional assessment and infectious diseases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6):1080–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53338_8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist J, Marmot M. Social inequalities in health: new evidence and policy implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O'Dowd T. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Zhang Z, Saliba D, Henry-Sanchez JT, Streim J. All-cause 1-, 5-, and 10-year mortality in elderly people according to activities of daily living stage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theou O, Rockwood MR, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Disability and co-morbidity in relation to frailty: how much do they overlap? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Ho SC, Lau J, Yuen YK, Chiu H, Lee HC, Chi I. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and predisposing factors in an elderly Chinese population. Acta psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Lau E, Lee P, Kwok T, Lau WC, Chan C, Chiu P, Li E, Sham A, Lam D. Impact of osteoarthritis on quality of life in a Hong Kong Chinese population. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(12):2433–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Leung J, Lau E. Prevalence and correlates of musculoskeletal pain in Chinese elderly and the impact on 4-year physical function and quality of life. Public Health. 2009;123(8):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Leung J, Morley JE. Comparison of frailty indicators based on clinical phenotype and the multiple deficit approach in predicting mortality and physical limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1478–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Leung J, Sham A, Kwok T. Defining sarcopenia in terms of risk of physical limitations: a 5-year follow-up study of 3,153 Chinese men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2224–2231. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Lynn H, Leung J, Wong SY. Self-perceived social status and health in older Hong Kong Chinese women compared with men. Women Health. 2008;48(2):209–234. doi: 10.1080/03630240802313563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]