SUMMARY

In marmoset T cells transformed by Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), a viral U-rich noncoding RNA, HSUR 1, specifically mediates degradation of host microRNA-27 (miR-27). High-throughput sequencing of RNA after crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) identified mRNAs targeted by miR-27 as enriched in the T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway, including GRB2. Accordingly, transfection of miR-27 into human T cells attenuates TCR-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and induction of CD69. MiR-27 also robustly regulates SEMA7A and IFN-γ, key modulators and effectors of T-cell function. Knockdown or ectopic expression of HSUR 1 alters levels of these proteins in virally-transformed cells. Two other T-lymphotropic γ-herpesviruses, AlHV-1 and OvHV-2, do not produce a noncoding RNA to downregulate miR-27, but instead encode homologs of miR-27 target genes. Thus, oncogenic γ-herpesviruses have evolved diverse strategies to converge on common targets in host T cells.

Keywords: Noncoding RNA, MicroRNA, T-cell activation, Viral evolution, HITS-CLIP

INTRODUCTION

Gamma-herpesviruses establish latent infection in lymphocytes that persists for the life of the host. Lymphocyte activation accompanies infection and it is well known that activation of infected lymphocytes requires expression of latent viral genes (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). Yet the mechanism by which latent genes control T-lymphocyte activation is poorly understood.

Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) is an oncogenic γ-herpesvirus that belongs to the rhadinovirus family. HVS undergoes asymptomatic lytic replication in its natural host, the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus), whereas latent infection progresses to acute T-cell lymphomas and leukemias in other New World primates, such as the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005). HVS-transformed marmoset cells are predominantly activated CD8 cytotoxic T cells (Johnson and Jondal, 1981; Kiyotaki et al., 1986). HVS is also capable of transforming human T cells in vitro (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005).

Noncoding (nc) RNAs play important roles in gene regulation. Like their host cells, viruses sometimes produce ncRNAs to modulate gene expression to benefit the viral life cycle or to counteract host anti-viral defense mechanisms (Skalsky and Cullen, 2010; Steitz et al., 2011). The most abundant transcripts in HVS-infected marmoset T cells are seven small U-rich ncRNAs, known as HSURs, which share biogenesis and other features with the cellular Sm-class U-rich RNAs (Albrecht and Fleckenstein, 1992; Lee et al., 1988; Wassarman et al., 1989). Although HSURs are not required for in vitro transformation, T cells transformed by an HVS strain lacking HSURs 1 and 2 (Δ2A cells) grow significantly slower than cells transformed by wildtype virus (WT cells) (Murthy et al., 1989).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are ~22 nucleotide (nt) endogenous ncRNAs that complex with Argonaute (Ago) proteins and form base-pairing interactions with messenger RNA (mRNA) targets to regulate protein production (Bartel, 2009). Cellular miR-27 is a highly conserved vertebrate miRNA with several known mRNA targets (summarized in Table S1). MiR-27 is ubiquitously expressed in many tissues and cell types. However, T cells express the highest levels of miR-27 (Kuchen et al., 2010), suggesting that miR-27 functions in regulating T-cell responses.

T-cell receptor/CD3 complex (TCR) signaling is important for proliferation, differentiation and cell death during T-cell development; it also contributes to clonal expansion and effector cytokine secretion during T-cell activation (Murphy et al., 2008). Ligand binding and crosslinking of the TCR activate the TCR signaling pathway through adaptor proteins, such as the growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2), leading to the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Jang et al., 2009). T-cell activation induces many cell surface and secreted molecules, such as semaphorin 7A (SEMA7A) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which are critical for T-cell mediated immune responses (Schroder et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 2008). IFN-γ has been shown to block reactivation of a γ-herpesvirus from latency (Steed et al., 2006), and SEMA7A homologs are found in the genomes of γ-herpesviruses and poxviruses (Comeau et al., 1998; Russell et al., 2009). However, the general importance of TCR signaling, SEMA7A and IFN-γ in the biology of γ-herpesviruses remains unclear.

In HVS-transformed marmoset T cells, the most conserved HSUR, HSUR 1, base-pairs with miR-27, targeting it for rapid decay in a sequence-specific and binding- dependent manner (Cazalla et al., 2010). However, the biological significance of miR-27 downregulation remained unknown. Since genes that are hallmarks of T-cell activation are selectively upregulated by HSUR 1 and/or 2 in HVS-infected marmoset T cells (Cook et al., 2005) and constitutive activation of TCR signaling molecules have been observed in HVS-transformed human T cells (Noraz et al., 1998), we asked whether miR-27 might be the missing link between HVS infection and T-cell activation.

RESULTS

Identification of miR-27 targets

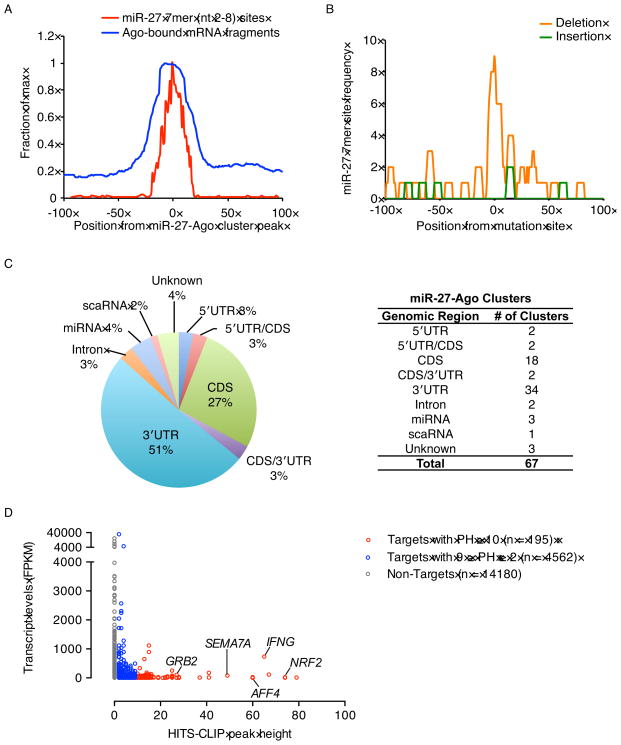

To identify miR-27 mRNA targets genome-wide in HVS-transformed marmoset T cells, we performed high-throughput sequencing of RNA after crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) (Chi et al., 2009). We used Δ2A cells, which have higher levels of miR-27 due to the lack of HSUR 1 (Cazalla et al., 2010), and performed four replicates using two different anti-Ago antibodies. Ago binding sites, composed of overlapping Ago-bound mRNA fragments that contain 7mer miR-27 seed (nt 2-8) binding sites, are referred to as miR-27-Ago clusters. The Ago-bound mRNA fragments and miR-27 binding sites were plotted relative to the centers of the miR-27-Ago clusters, revealing that the peaks of the two distributions overlap at the centers of the miR-27-Ago clusters (Figure 1A), as reported for miRNA-mediated Ago footprints (Chi et al., 2009). UV crosslinking-induced mutation sites (CIMS) are generated during the reverse transcription step in HITS-CLIP because of the crosslinked amino-acid-RNA adduct. Analyses of statistically significant (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.001) CIMS revealed high frequencies of miR-27 binding sites near deletions (Figure 1B), evidence of in vivo Ago-mRNA interactions (Zhang and Darnell, 2011).

Figure 1. Identification of miR-27 targets by HITS-CLIP.

(A) Distribution of Ago-bound mRNA fragments correlates with miR-27 seed (7mer) binding sites. Ago-bound mRNA fragments and miR-27 (7mer) binding sites were plotted relative to the centers (set to 0 nt) of 2279 miR-27-Ago clusters (PH ≥ 2).

(B) Enrichment of miR-27 binding sites around Ago-mRNA crosslinking sites. MiR-27 7mer seed binding sites were plotted relative to statistically significant (FDR < 0.001) CIMS including deletion and insertion sites. Insertions are not induced by Ago-mRNA crosslinks (Zhang and Darnell, 2011), serving as a control.

(C) Genomic locations of the 67 statistically significant miR-27-Ago clusters (p-value ≲ 0.05, BC ≥ 3 and PH ≥ 10). 5′UTR/CDS indicates clusters mapping to the junctions of 5′UTRs and CDSs. 3′UTR/CDS clusters mapped to the junctions of 3′UTRs and CDSs.

(D) Peak height (PH) values for miR-27-Ago clusters were plotted against transcript levels.

See also Figure S1.

In total, we identified 67 statistically significant (p-value ≲ 0.05) miR-27-Ago clusters with a minimum of 10 Ago-bound mRNA fragments per cluster (peak height (PH) ≥ 10) in at least three replicates (biological complexity (BC) ≥ 3) (Table S2). Of these, 51% mapped to the 3′UTRs and 27% mapped to the coding sequences (CDSs) of 58 annotated host mRNAs (Figure 1C). We did not find any significant miR-27-Ago clusters that mapped to the HVS genome (data not shown). To confirm the selectivity of HITS-CLIP and whether our analysis might be erroneously detecting abundant mRNAs, we plotted the peak height of miR-27-Ago clusters against the abundance of mRNA transcripts to which these clusters mapped (Figure 1D); no correlation was observed, indicating specific enrichment of miR-27 targets. Moreover, we collectively validated HITS-CLIP-identified miR-27 targets using an independent approach. Transcripts containing statistically significant miR-27-Ago clusters showed expression changes based on mRNA-Seq analysis after HSUR 1 knockdown or miR-27 inhibition in HVS-infected T cells. Specifically, mRNA levels of identified miR-27 targets were lower relative to non-targets upon HSUR 1 knockdown in WT cells (Figure S1A) and higher upon transfection of a locked nucleic acid (LNA) inhibitor of miR-27 in Δ2A cells (Figure S1B). These analyses indicate that Ago HITS-CLIP identified high-quality miR-27 targets.

Gene ontology (GO) analyses reveal that miR-27 regulates TCR signaling and downstream effector cytokines

We used GO analyses to identify cellular pathways regulated by miR-27 in HVS-transformed T cells. A total of 58 unique mRNA targets containing statistically significant miR-27-Ago clusters (p-value ≲ 0.05, BC ≥ 3 and PH ≥ 10) in their 5′UTRs, 3′UTRs or CDSs were included in the query gene list; all transcripts in Δ2A cells identified by mRNA-Seq with fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) ≥ 1 were used as background. Among the top 10 enriched pathways, the TCR signaling pathway (Figure 2A), including the PTPRC/CD45, PLCG1, PIK3CD, GRB2 and IFNG genes, was the most highly enriched (p-value = 4.6×10−7) (Figures S2A, S2B and S3A–S3C). Comparable analyses demonstrated that the TCR pathway or T-cell-specific genes were not targeted by a control miRNA, miR-30 (Figures S2C and S2D), which has an unrelated seed sequence and is expressed at levels similar to miR-27 (Figure S2E).

Figure 2. MiR-27 regulates TCR signaling components and effector molecules of T-cell activation.

(A) The TCR signaling pathway is significantly enriched among HITS-CLIP-identified miR-27 targets. Percent of miR-27 mRNA targets in each GO pathway is indicated. FDR, false discovery rate.

(B) Genes containing the 10 most robust miR-27-Ago clusters in their 3′UTRs. *Genes of unknown biological function. Genes studied further are highlighted in red.

(C) Schematic depicting miR-27 as a repressor of three key modulators or effectors of T-cell activation, SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFN-γ. Diagram drawn based on (Suzuki et al., 2008). ? denotes a possible interaction between SEMA7A and integrin (Liu et al., 2010).

See also Figures S2 and S3.

In addition to the HITS-CLIP-identified targets, many other components of the TCR signaling pathway are predicted targets with conserved miR-27 binding sites (Figure S2B). Ras and LCK, two additional TCR signaling molecules (Figure S2B), are activated by HVS-encoded proteins (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005) underscoring the importance of this pathway to HVS. It is interesting that T-cell activation genes previously documented as upregulated by HSUR 1 and/or 2 in HVS-transformed T-cell lines (Cook et al., 2005) do not have confirmed or predicted miR-27 binding sites; they may be indirect targets, or their upregulation may be due to other causes.

MiR-27 represses T-cell activation

To test directly miR-27’s role in T-cell activation, we compared MAPK activation and CD69 induction in human Jurkat T cells transiently transfected with synthetic miR-27 or a scrambled control after TCR crosslinking by anti-CD3 antibody. Despite relatively minor changes in TCR-induced total tyrosine phosphorylation (Figures S4A and S4B), miR-27 significantly repressed activation of MAPKs. Activation of the p46 isoforms of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) was significantly weaker in cells transfected with synthetic miR-27 relative to the scrambled control two minutes post-stimulation, when activation peaks (Figure 3A). Similarly, p38 activation was attenuated in T cells transfected with miR-27 at 2, 5 and 10 minutes after stimulation compared to the control (Figure 3B). In contrast, the extent and kinetics of activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) were similar in cells transfected with miR-27 versus the scrambled control (Figure S4C). Further, upregulation of CD69, a cell surface marker induced early upon T-cell activation, was decreased after TCR crosslinking of cells transfected with miR-27 relative to the scrambled control (Figure 3C). Together, these results indicate that miR-27 is a pleiotropic repressor of TCR-mediated activation.

Figure 3. MiR-27 attenuates activation of JNKs and p38, as well as induction of CD69.

(A) Jurkat T cells transfected with miR-27 or a scrambled control were stimulated by anti-CD3 antibody for the indicated times. The JNK activation profile was determined by Western blot analysis (WB) for phosphorylated JNKs (P-JNK) and total JNKs (JNK). Relative quantity = (phosphorylated kinase signal intensity)/(total kinase signal intensity). Non-stimulated sample (i.e. 0 minute time point) was set to 1. In repeat experiments, the p54 isoform of JNKs was only slightly activated, and no significant difference in activation was observed between miR-27 and the scrambled control (data not shown).

(B) The p38 activation profile was determined as described in (A).

(C) FACS data and histogram show CD69 expression in Jurkat cells transfected with miR-27 or the scrambled control with (Act) and without (Non) activation by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Values are means ± SD in three experiments; p-values were determined by Student’s t-test. * p-value < 0.05; ** p-value < 0.01. See also Figure S4.

Key modulators and effectors of T-cell activation are regulated by HSUR 1 via miR-27

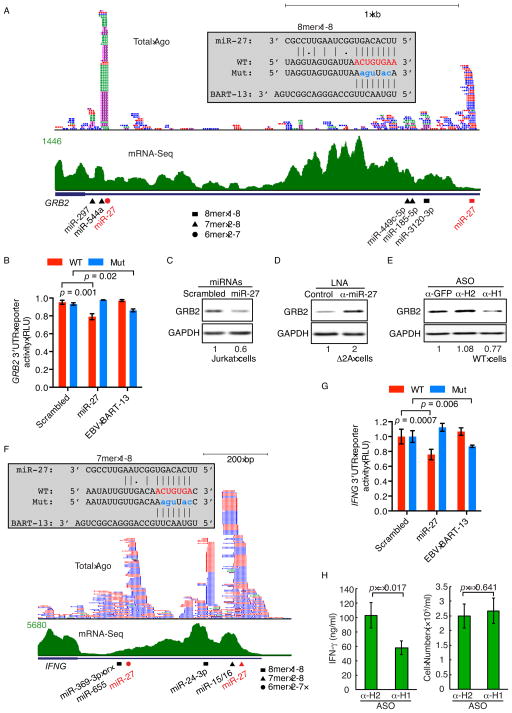

Genes possessing the 10 most robust miR-27-Ago clusters in their 3′UTRs are shown in Figure 2B. Included are two transcription factors associated with human leukemias—nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2/NFE2L2) (Rushworth et al., 2012) and AF4/FMR2 family member 4 (AFF4) (Lin et al., 2010) (Figures S3D and S3E). Three targets—SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFNG—were selected for validation because they are key regulators or effectors of T-cell activation (Jang et al., 2009; Schroder et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 2008) (Figure 2C). The two miR-27-Ago clusters in the SEMA7A 3′UTR each contain a conserved 8mer (nt 1-8) target site (Figures 4A and S5A); the GRB2 3′UTR possesses one miR-27-Ago cluster, with a conserved 8mer (nt 1-8) target site (Figures 5A and S5B); and the miR-27-Ago cluster in the IFNG 3′UTR corresponds to a 7mer (nt 2-8) target site (Figure 5F).

Figure 4. HSUR 1 regulates SEMA7A through miR-27 degradation.

(A) Ago-bound mRNA fragments from four HITS-CLIP replicates (different colors), mRNA-Seq reads and predicted miRNA target sites are mapped on the marmoset SEMA7A 3′UTR. Base-pairing interactions between miR-27 or EBV BART-13 and the WT (red) or mutant (Mut, blue) target sites in the reporters used in (B) are shown. A gap in the marmoset reference genome (grey bar) was sequenced.

(B) Luciferase reporter assays performed with full-length WT or Mut SEMA7A 3′UTR in HEK293T cells transfected with synthetic WT, scrambled miR-27 or EBV BART-13. RLU, relative luciferase units.

(C) WB of SEMA7A in Jurkat cells transfected with WT or scrambled miR-27.

(D) WB of SEMA7A in Δ2A cells transfected with a miR-27 LNA inhibitor or control.

(E) WT cells transfected with an ASO against HSUR 1 (α-H1), HSUR 2 (α-H2) or GFP (α-GFP) were subjected to WB for SEMA7A and Northern blot analysis (NB) for miRNAs and HSURs.

Values are means ± SD in three experiments; p-values were determined by Student’s t-test. See also Figure S5.

Figure 5. GRB2 and IFN-γ are regulated by HSUR 1 via miR-27.

(A) Ago-bound mRNA fragments, mRNA-Seq reads and predicted miRNA binding sites are mapped on the marmoset GRB2 3′UTR as in Figure 4. Base-pairing interactions between miR-27 or EBV BART-13 and WT or a Mut 8mer target site are shown.

(B) Luciferase reporter assays were performed with the full-length WT or Mut GRB2 3′UTR as described in Figure 4.

(C) WB of GRB2 after transfection of WT or scrambled miR-27 into Jurkat cells.

(D) WB of GRB2 in Δ2A cells transfected with a miR-27 LNA inhibitor or control.

(E) WB of GRB2 in WT cells after transfection with α-H1, α-H2 or α-GFP ASO.

(F) Ago-bound mRNA fragments, mRNA-Seq reads and predicted miRNA binding sites are mapped on the marmoset IFNG 3′UTR as in Figure 4. Base-pairing interactions between miR-27 or EBV BART-13 and the WT or a Mut 7mer target site are shown.

(G) Luciferase reporter assays were performed with the full-length WT or Mut IFNG 3′UTR as described in Figure 4.

(H) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measured extracellular IFN-γ concentration after knockdown of HSUR 1 with α-H1 compared to α-H2 ASO. The cell number was determined before harvesting.

The 6mer miR-27 sites (

) in both the GRB2 and IFNG 3′UTRs were not active enough to be detected in luciferase reporter assays (data not shown).

) in both the GRB2 and IFNG 3′UTRs were not active enough to be detected in luciferase reporter assays (data not shown).

Values are means ± SD in at least three experiments; p-values were determined by Student’s t-test. See also Figure S5.

Luciferase reporter assays using the full-length WT 3′UTRs of SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFNG mRNAs showed repression after transient transfection of synthetic miR-27, but not scrambled miR-27, into HEK293T cells; mutations in the miR-27 binding sites abolished the repression, whereas an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) miRNA BART-13, complementary to the mutated seed binding sites, represses the mutant reporters (Figures 4B, 5B and 5G). Synthetic miR-27 induced decreases of typical magnitude (Bartel, 2009) in endogenous SEMA7A and GRB2 protein levels in Jurkat T cells compared to scrambled miR-27 (Figures 4C and 5C). Transfection of a miR-27 antisense LNA into Δ2A cells increased levels of SEMA7A and GRB2 protein relative to a control LNA (Figures 4D and 5D). Importantly, RNase-H targeted knockdown of HSUR 1 in WT cells using an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) increased miR-27 levels and decreased the levels of SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFN-γ proteins relative to an ASO against HSUR 2 or GFP (Figures 4E, 5E and 5H).

Conversely, a lentiviral vector expressing WT HSUR 1 (at levels similar to those in WT cells (data not shown)), but not HSUR 1 with its miR-27 binding site mutated (Mut HSUR 1), decreased miR-27 levels in both Jurkat and Δ2A cells (Figures 6A–6D). Likewise, only WT HSUR 1 increased levels of SEMA7A and GRB2 proteins in lentiviral infected Δ2A cells (Figures 6E and 6F). IFN-γ levels were also tested but no difference observed, possibly because lentiviral infection induces IFN-γ, which masks any change due to miR-27 degradation (data not shown). This rescue approach is preferable to confirming the effects of HSUR1 by generating multiple HVS-transformed cell lines; it eliminates the possibility that secondary alterations acquired by the WT or Δ2A cells during propagation in culture could account for any gene expression differences. Together, the HSUR 1 knockdown (Figures 4E, 5E and 5H) and rescue (Figure 6) experiments argue that HVS upregulates SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFN-γ by producing HSUR 1 to induce miR-27 degradation.

Figure 6. Wildtype (WT), but not a miR-27 binding site-mutated (Mut) HSUR 1, rescues levels of miR-27 target proteins in Δ2A cells.

(A) Sequence of the WT and Mut HSUR 1, with nucleotides conserved between HVS strains in bold. Mutations introduced into the miR-27 binding site are highlighted in red; the miR-27 seed is in yellow.

(B) NB shows that Jurkat T cells infected with lentiviruses carrying WT HSUR 1 have lower levels of miR-27 compared to cells infected with lentiviruses carrying Mut HSUR 1. Quantifications of miR-27 levels relative to miR-16 are given below.

(C) NB shows levels of WT and Mut HSUR 1 expressed by lentiviruses in Δ2A cells.

(D) Levels of miR-27 and a control, miR-181a, in Δ2A cells infected with lentiviruses carrying WT or Mut HSUR 1, determined by Q-PCR. Endogenous U6 snRNA was the normalization control for the quantifications.

(E) WB of SEMA7A in Δ2A cells infected with lentiviruses carrying WT or Mut HSUR 1. zsGreen is a marker protein expressed by the pAGM lentiviral transfer vector. GAPDH provided a loading control for the quantifications below.

(F) GRB2 levels in Δ2A cells rescued with WT or Mut HSUR 1 as described above. Values are means ± SD in two experiments.

Alternative capture of miR-27 targets by other viruses

To determine whether similar strategies are used by γ-herpesviruses of other genera, we examined Herpesvirus ateles (HVA), a rhadinovirus related to HVS, and two macaviruses, Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 (AlHV-1) and Ovine herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2). Like the rhadinoviruses, the macaviruses A1HV-1 and OvHV-2 cause apathogenic infections in their natural hosts (wildebeest and sheep, respectively), but in related ruminants cause fatal T-lymphoproliferative disease called malignant catarrhal fever (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). All four of these γ-herpesviruses (highlighted in red in Figure 7B) establish latency in host CD8 T cells, promoting constitutive activation of TCR signaling molecules, clonal expansion and expression of activation markers, including high levels of IFN-γ secretion (Dewals and Vanderplasschen, 2011; Johnson and Jondal, 1981; Kiyotaki et al., 1986; Nelson et al., 2010; Noraz et al., 1998).

Figure 7. Gene maps and phylogenetic tree of T-lymphotropic γ-herpesviruses.

(A) Syntenic regions flanked by H-DNA and ORF3 (formylglycineamide ribotide amidotransferase, FGARAT) are shown (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). STP-A11, Saimiri transformation protein of HVS strain A11; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; Tio, two-in-one protein of HVA; HSUR and HAUR, HVS- and HVA-encoded URNA, respectively; A1, A2, A3 and A4, AlHV-1 ORFs; Ov2, Ov2.5, Ov3 and Ov3.5, OvHV-2 ORFs; v-ATF3, v-IL10 and v-SEMA7A, viral homologs of cellular proteins.

(B) Phylogenetic tree of commonly studied γ-herpesviruses with T-lymphotropic viruses in red. EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; KSHV, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; MHV-68, Murid herpesvirus 68.

See also Figures S6 and S7.

HVA encodes homologs of HSURs 1 and 2, called HAURs 1 and 2 (Figure 7A), with the miR-27 binding sites conserved between HSUR 1 and HAUR 1 (Cazalla et al., 2010). The macaviruses AlHV-1 and OvHV-2 do not appear to encode HSUR homologs. Instead, in the syntenic region of their genomes, homologs of the host miR-27 target genes SEMA7A, ATF3 and IL10 appear (Figure 7A). Although our HITS-CLIP did not reveal miR-27-Ago clusters in the marmoset ATF3 or IL10 3′UTRs (probably because of low mRNA expression), both mRNAs are predicted miR-27 targets with conserved binding sites in their 3′UTRs (Figures S6A–S6C and S6E). The use of diverse mechanisms by different γ-herpesviruses to enhance expression of the same genes underscores the importance of these genes to the viral life cycle and T-cell function.

DISCUSSION

Here we have addressed the question of why an oncogenic γ-herpesvirus HVS produces the ncRNA, HSUR 1, to induce degradation of a conserved host miRNA, miR-27. We have shown that miR-27 is a pleiotropic repressor of T-cell activation that targets TCR signaling pathway components and downstream effector cytokines. These results provide a molecular mechanism whereby the degradation of miR-27 by HSUR 1 contributes to the constitutive activation of HVS-infected T cells. The unexpected finding that we further present involves two other oncogenic γ-herpesviruses, the macaviruses AlHV-1 and OvHV-2. These viruses, instead of making a ncRNA to degrade miR-27, encode in the syntenic region viral homologs of miR-27 target genes. Thus, our findings reveal that γ-herpesviruses evolved diverse mechanisms—host miRNA degradation or acquisition of miRNA target genes—to regulate common targets to ensure activation of virally-transformed T cells.

A few miRNAs such as miR-146a, miR-155, miR-17-92, miR-181a, have been shown to regulate genes important for T-cell development and function (Baumjohann and Ansel, 2013). Here, we have shown that miR-27 regulates key modulators and effectors of T-cell activation, including SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFN-γ.

SEMA7A is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell-surface protein that is upregulated in activated lymphocytes and plays important roles in T-cell mediated inflammatory responses (Czopik et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2008). Both soluble and membrane-associated forms of SEMA7A stimulate monocytes/macrophages (Holmes et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2008). For cellular SEMA7A, two receptors have been identified, PlexinC1 (Tamagnone et al., 1999) and α1β1 integrin (Suzuki et al., 2008), although the human SEMA7A X-ray crystal structure suggests that integrin interacts indirectly (Liu et al., 2010). A viral SEMA7A homolog encoded by a poxvirus, Vaccinia virus (VACV) A39R, also stimulates human monocytes and promotes secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by binding PlexinC1 (Comeau et al., 1998). The amino acids that confer high-affinity PlexinC1 binding are particularly well conserved between A39R and human SEMA7A (Liu et al., 2010). Sequence alignment reveals that the same residues are also conserved in macaviral SEMA7A homologs (A3 and Ov3) (Figures S7A and S7B) and homology modeling of A3 to the human SEMA7A crystal structure suggests comparable binding to PlexinC1 (Figures S7C–S7G). Thus, these viral homologs are likely to function similarly to cellular SEMA7A.

GRB2 is an adaptor protein downstream of the TCR that is crucial for the activating phosphorylation of MAPKs (Jang et al., 2009). GRB2 haploinsufficiency causes defects in JNK and p38 activation (Gong et al., 2001), similar to miR-27 overexpression (Figures 3A and 3B). JNK and p38 signaling are important in proliferation and differentiation of T cells (Rincon and Pedraza-Alva, 2003). It is possible that HVS exploits MAPK signaling to ensure proliferation of transformed CD8 T cells to maintain the virally-infected pool. The macavirus AlHV-1 also promotes activation and clonal expansion of a homogeneous population of latently-infected CD8 T cells in animal models (Dewals and Vanderplasschen, 2011). The activation of JNKs and p38 further promotes IFN-γ production by CD8 T cells (Manning and Davis, 2003; Rincon and Pedraza-Alva, 2003), which should enhance viral latency since IFN-γ is a potent inhibitor of lytic reactivation of γ-herpesviruses (Steed et al., 2006).

Consistent with this notion, our study found that IFN-γ is a target of miR-27, which is degraded by HSUR 1. In addition, we found ATF3, a transcriptional activator that drives IFNG expression (Filen et al., 2010), to be a predicted target of miR-27. AlHV-1 infection has been reported to lead to high levels of IFN-γ secretion by infected CD8T cells in animal models (Dewals and Vanderplasschen, 2011), but IFN-γ levels are significantly reduced upon infection by an A3 (SEMA7A homolog) knockout strain (Myster, 2011). This observation is in agreement with our demonstration that the knockdown of HSUR 1 reduces levels of IFN-γ (Figure 5H) and supports the conclusion that degradation of miR-27 by HVS produces consequences similar to expression of the miR-27 target homolog by AlHV-1. Thus, we speculate that constitutive expression of IFN-γ in transformed T cells maintains the viral genome in latency and provides a long-term sustained viral infection within the host.

The rhadinoviruses, HVS and HVA, and the macaviruses, AlHV-1 and OvHV-2, are similar in that they cause apathogenic lytic infections in their natural hosts, but latently infect cytotoxic CD8 T cells in related species causing T-lymphoproliferative disease (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). The genomes of these viruses are composed of blocks of genes highly conserved between the herpesvirus families in co-linear organization with a few genes unique to each virus interspersed between the blocks. Among the open reading frames (ORFs) encoded by the four viruses (76 for HVS, 73 for HVA, 71 for AlHV-1 and 73 for OvHV-2), at least 60 ORFs exhibit homology to those of other herpesviruses (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). However, there is extensive diversity at a few “hot spots” in the viral genomes. Genes unique to each virus tend to cluster at the left end of the genome next to the terminal heavy-DNA repeats (H-DNA) and in the region of the R transactivator gene ORF50 and the glycoprotein gene ORF51 (Ensser and Fleckenstein, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). Indeed, the viral ncRNAs (HSURs and HAURs in HVS and HVA, respectively) and miR-27-target gene homologs (v-SEMA7A, v-ATF3 and v-IL10 in AlHV-1 and OvHV-2) all appear adjacent to the left H-DNA terminus (see Figure 7A).

Interestingly, similar alternative approaches for enhancing host-cell gene expression may also operate in β-herpesviruses. Mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) degrades miR-27 using an antisense mechanism similar to HVS (Libri et al., 2012; Marcinowski et al., 2012), while human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) does not alter miR-27 levels. We noted that HCMV and OvHV-2 encode viral IL10 homologs (Russell et al., 2009; Slobedman et al., 2009) (see also Figure 7A). Luciferase reporter assay results and sequence conservation argue that cellular IL10 is a miR-27 target (Figures S6C–S6E). Together, these results suggest that MCMV upregulates cellular IL-10 by degrading miR-27, whereas HCMV instead expresses a viral IL-10 homolog. HCMV IL-10 binds the same receptor as human IL-10, and the immunomodulatory functions of human IL-10 are shared by HCMV IL-10. Virus-encoded IL-10 homologs have been identified in many herpesviruses and poxviruses and are likely to be exploited by viruses for successful infection (Slobedman et al., 2009).

Our study highlights two completely separate strategies evolved by viruses—miRNA degradation or viral co-option of miRNA targets—to ensure overexpression of the same set of genes. Such parallel mechanisms may be applicable to other viral-host interactions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture and transfection

T cells from common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) immortalized by wildtype HVS strain A11 (WT cells) or a deletion mutant lacking HSURs 1 and 2 (Δ2A cells) (Murthy et al., 1989) were cultured as described (Cook et al., 2004). HEK 293T cells and Jurkat T cells were grown in DMEM and RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine.

One million Jurkat T cells were transfected with 200 pmol synthetic miR-27 or scrambled miR-27 (IDT) per cuvette using the 4D-Nucleofector SE cell line kit (program CL-120) from Lonza. Cells were harvested 48 hours post-transfection for Western blot analyses.

Ten million Δ2A cells were transfected with 300 pmol tiny LNAs against miR-27 (Exiqon; designed according to (Obad et al., 2011)) per cuvette using the 4D-Nucleofector SE cell line kit (program CM-138) from Lonza. Transfected cells were then transferred to complete media and incubated at 37°C. After 48 hours, cells were harvested for Western blot analyses.

Ten million WT cells were transfected, as described above for Δ2A cells, with 300 pmol chimeric ASOs against GFP (α-GFP), HSUR 1 (α-H1) and HSUR 2 (α-H2) (IDT; designed according to (Cazalla et al., 2010)). After 24 hours, cells were harvested and split into two aliquots, one for Western blot analysis and the other for RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis.

Ago HITS-CLIP

Four biological replicates of the HITS-CLIP experiment were performed in Δ2A cells according to (Chi et al., 2009), using two anti-Argonaute antibodies, clone 2A8 (Nelson et al., 2007) (a gift from Z. Mourelatos) and 11A9 (Rudel et al., 2008) (Sigma), each in duplicate. For each library, 5 million Δ2A cells were irradiated with 600 mJ/cm2 254 nm UV on ice in a Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene), lysed and digested with RNase A (USB 70194Y). Ago-mRNA complexes were isolated, reverse transcribed and PCR amplified to prepare cDNA libraries. In total, four Ago-mRNA cDNA libraries were deep-sequenced by the Yale Stem Cell Center Genomics Core on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument using 50 bp runs. About 100 and 250 million reads were generated for the two libraries prepared with 2A8 antibody; 170 million reads were generated for each of the two 11A9 libraries. Raw sequencing reads were filtered by quality, collapsed and selected for 7mer miR-27 seed nt 2–8 binding sites using tools on the Galaxy server (http://galaxy.psu.edu) (Blankenberg et al., 2010; Giardine et al., 2005; Goecks et al., 2010). The miR-27 reads and total reads were mapped onto the marmoset reference genome (version caljac 3.2) with Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) allowing a maximum of 2 mismatches. Uniquely mapped reads were collapsed again based on their genome coordinates and the degenerate barcode to obtain unique Ago-bound mRNA fragments. This analysis was performed using Dr. Robert Darnell’s lab server (Rockefeller University) as described in the Extended Experimental Procedure in (Darnell et al., 2011). Total Ago and miR-27-Ago clusters were formed by grouping overlapping unique Ago-bound mRNA fragments with a minimum of 1-nt overlap. Clusters were visualized on the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and ranked based on biological complexity (BC) and peak height (PH). To identify target sites for other miRNAs, 8mer, 7mer and 6mer seed binding sites were searched for among robust Ago clusters.

To evaluate the robustness of the miR-27-Ago clusters in multiple experiments, the chi-squared test was used considering both biological complexity and the number of Ago-bound mRNA fragments in individual experiments; p-value (before multiple test correction) was determined from chi-squared test scores according to (Darnell et al., 2011). Details on plotting the distribution of Ago-bound mRNA fragments relative to cluster peaks are given in the Figure 1A legend. The CIMS analysis was performed as described in (Zhang and Darnell, 2011); see Figure 1B legend for details.

mRNA-Seq

An mRNA-Seq library from Δ2A cells was prepared and sequenced at the Yale Center for Genomic Analysis. About 100 million raw reads were obtained from an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. The raw data were processed and mapped to the marmoset reference genome (version caljac 3.2) using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) on the Galaxy server (http://galaxy.psu.edu) and visualized on the UCSC genome browser. Transcript levels were quantified by Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010) using 55,137 transcripts annotated by Ensembl as a reference.

Luciferase reporter assays

HEK293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates 24 hours before transfection, and co-transfected with 5 ng of pmiRGLO luciferase reporter, 0.8 μg pBlueScript II and 20 pmol of synthetic miRNA per well using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Synthetic miRNA duplexes contained a 5′-phosphorylated mature miRNA with a 2-nt 3′-overhang and a complementary passenger stand, which were annealed according to (Tuschl, 2006). Twenty-four hours post-transfection, Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured in dual-luciferase reporter assays performed on a GloMax-Multi+ Microplate Multimode Reader (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luciferase activity was first normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and then the ratios were corrected against that of an empty reporter. Standard deviation (SD) for each condition was calculated based on a minimum of three independent experiments. p-values were calculated using one-tailed Student’s t-test.

Western blot analysis

Cell pellets were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, supplemented with complete EDTA-free proteinase inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche)), and quantified by Bradford assays using the Coomassie Plus Assay Kit (Pierce). Typically, 10 μg total protein was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad). After blocking with 5% milk in 1x TBST, the membrane was probed with the appropriate antibody, detected with SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, imaged using a GBox (SYNGENE) and quantified by GeneTools v. 4.02 (SYNGENE). We obtained standard curves for SEMA7A and GRB2 by making serial dilutions of total cell lysate. Both curves show a strong linear relationship between signal and the amount of cell lysate (data not shown). The Western blots presented in the paper were performed within the linear range. Primary antibodies used were anti-SEMA7A (sc-376149, Santa Cruz Biotech), anti-GRB2 (#3972, Cell Signaling), anti-GAPDH (#2118, Cell Signaling) and anti-TUBULIN (#CP06, DM1A, Calbiochem). GAPDH and TUBULIN were provided as normalization controls. Data shown in the figures are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Ten million WT cells were transfected with 300 pmol anti-HSUR 1 and anti-HSUR 2 oligonucleotides. At 48 hours post-transfection, cell numbers were quantified using a hemocytometer after staining with trypan blue (Gibco) and the growth media were harvested for ELISA. The IFN-γ concentration was measured using the Human IFN-γ Screening Set (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. SD for each data point was calculated based on three experiments. p-values were calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Lentiviral rescue of miR-27 targets in Δ2A cells with wildtype or mutant HSUR 1

Wildtype and miR-27 binding site-mutated HSUR 1 expression cassettes were made as described in (Cazalla et al., 2010) and inserted into the PacI site of the lentiviral transfer vector pAGM (Mayoral and Monticelli, 2010). Transcription of the HSUR 1 expression cassette is opposite to the zsGreen expression cassette. 25 μg transfer vector, 25 μg packaging vector (psPAX2) and 5 μg VSVG pseudo-typing vector (pMD2.G) were transfected into HEK293T cells in 150 mm tissue culture plates using ProFection Mammalian Transfection System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Supernatant was harvested 48 hours after transfection, filtered through 0.45 μm low protein binding membrane, then ultracentrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 2 hours at 4°C. The concentrated viruses were stored at −80°C until use. Viral titers were determined by transduction of HEK293T cells and counting GFP+ colonies.

About 2×105 Jurkat cells or Δ2A cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) 30 in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene (Millipore), and the total RNA was extracted 16 or 7 days, respectively, after infection for Northern blot analyses (Figures 6B and 6C). About 2×105 Δ2A cells were infected at MOI 100 in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene; cells were harvested 3 days after infection for Western blot analyses (Figures 6E and 6F). Anti-zsGreen antibody was purchased from Clontech (#632475). In addition, 2×105 Δ2A cells were infected at MOI 15 in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene, the GFP+ cells were sorted 3 days after infection, and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis (Figure 6D). Levels of mature miR-27 and miR-181a were determined using Taqman miRNA assays (#4427975, #4427975, Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. U6 snRNA (#4427975, Applied Biosystems) was used as a normalization control. Amplification was performed with a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and data were analyzed using StepOne software v2.2.2.

T-cell activation and MAPK phosphorylation

Jurkat cells were transfected with synthetic miR-27 or a scrambled control as described above, and harvested after 48 hours. Transfected cells were activated according to (Sawasdikosol, 2010), lysed directly in 1× Laemmli sample buffer, and separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3) was from eBiosciences (#16-0037), and secondary rabbit anti-mouse IgG antibody was from Southern Biotech (#6170). Typically 100,000 cells were loaded in each lane. Primary antibodies used for Western blot (Cell Signaling) include anti-phospho-JNK (#4668), anti-total-JNK (#9258), anti-phospho-p38 (#4511), anti-total-p38 (#9212), anti-phospho-ERK (#4370), anti-total-ERK (#4695) and anti-phospho-tyrosine (#9416).

CD69 induction and FACS analysis

Jurkat cells were transfected with synthetic miR-27 or a scrambled control as described above, and harvested after 46 hours. Transfected cells were activated by immobilized OKT3 (5 μg/ml) in the presence of soluble anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml; eBiosciences #16-0289) for 2 hours at 37°C. Activated cells were stained with anti-CD69 conjugated R-phycoerythrin (PE) (eBiosciences #12-0699) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, then analyzed on a FACSCalibur at the Yale FACS Core Facility. The data were analyzed using FlowJo (http://www.flowjo.com/) to generate the histogram and calculate the median fluorescence intensity, MFI.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

HITS-CLIP identifies miR-27 targets as enriched in the TCR signaling pathway.

MiR-27 represses TCR-mediated MAPK activation and CD69 induction.

HSUR 1 regulates SEMA7A, GRB2 and IFN-γ through miR-27 degradation.

Herpesviruses evolved miRNA degradation or acquired homologs of host genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Darnell, C. Zhang and J. Luna for help with bioinformatic analyses of HITS-CLIP data; D. Bartel for suggestions on miR-27 target prediction; D. Cazalla, K. Tycowski and other members of the Steitz laboratory for helpful discussion; Z. Mourelatos for anti-Ago antibodies (2A8); P. Kumar and S. Zeller for the pAGM vector; S. Zeller, N. Lee and S. Liu for protocols to make lentivirus; S. Takyar and T. Yarovinsky for advice on T-cell activation assays; J. Brown, D. DiMaio, G. Miller, E. Ullu and J. Withers for critical commentary on the manuscript; and A. Miccinello for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grant CA16038 from the NIH.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Gene expression data (i.e. mRNA-Seq) have been deposited in NCBI’s the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE55185.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.E.G. performed the experiments and analyses. K.J.R. helped with HITS-CLIP. A.I. helped with immunology-related experiments. Y.E.G. and J.A.S wrote the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. J.A.S is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albrecht JC, Fleckenstein B. Nucleotide sequence of HSUR 6 and HSUR 7, two small RNAs of herpesvirus saimiri. Nucleic acids research. 1992;20:1810. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumjohann D, Ansel KM. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of T helper cell differentiation and plasticity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:666–678. doi: 10.1038/nri3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. In: Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Current protocols in molecular biology. Unit 19. Ausubel Frederick M, et al., editors. Chapter 19. 2010. pp. 10pp. 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla D, Yario T, Steitz JA. Down-regulation of a host microRNA by a Herpesvirus saimiri noncoding RNA. Science. 2010;328:1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1187197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau MR, Johnson R, DuBose RF, Petersen M, Gearing P, VandenBos T, Park L, Farrah T, Buller RM, Cohen JI, et al. A poxvirus-encoded semaphorin induces cytokine production from monocytes and binds to a novel cellular semaphorin receptor, VESPR. Immunity. 1998;8:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook HL, Lytle JR, Mischo HE, Li MJ, Rossi JJ, Silva DP, Desrosiers RC, Steitz JA. Small nuclear RNAs encoded by Herpesvirus saimiri upregulate the expression of genes linked to T cell activation in virally transformed T cells. Current biology : CB. 2005;15:974–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook HL, Mischo HE, Steitz JA. The Herpesvirus saimiri small nuclear RNAs recruit AU-rich element-binding proteins but do not alter host AU-rich element-containing mRNA levels in virally transformed T cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:4522–4533. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4522-4533.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czopik AK, Bynoe MS, Palm N, Raine CS, Medzhitov R. Semaphorin 7A is a negative regulator of T cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KY, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewals BG, Vanderplasschen A. Malignant catarrhal fever induced by Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 is characterized by an expansion of activated CD3+CD8+CD4− T cells expressing a cytotoxic phenotype in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues. Veterinary research. 2011;42:95. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensser A, Fleckenstein B. T-cell transformation and oncogenesis by gamma2-herpesviruses. Advances in cancer research. 2005;93:91–128. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(05)93003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filen S, Ylikoski E, Tripathi S, West A, Bjorkman M, Nystrom J, Ahlfors H, Coffey E, Rao KV, Rasool O, et al. Activating transcription factor 3 is a positive regulator of human IFNG gene expression. J Immunol. 2010;184:4990–4999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P, Zhang Y, Blankenberg D, Albert I, Taylor J, et al. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome research. 2005;15:1451–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome biology. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Q, Cheng AM, Akk AM, Alberola-Ila J, Gong G, Pawson T, Chan AC. Disruption of T cell signaling networks and development by Grb2 haploid insufficiency. Nature immunology. 2001;2:29–36. doi: 10.1038/83134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S, Downs AM, Fosberry A, Hayes PD, Michalovich D, Murdoch P, Moores K, Fox J, Deen K, Pettman G, et al. Sema7A is a potent monocyte stimulator. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2002;56:270–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IK, Zhang J, Gu H. Grb2, a simple adapter with complex roles in lymphocyte development, function, and signaling. Immunological reviews. 2009;232:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Jondal M. Herpesvirus ateles and herpesvirus saimiri transform marmoset T cells into continuously proliferating cell lines that can mediate natural killer cell-like cytotoxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:6391–6395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyotaki M, Desrosiers RC, Letvin NL. Herpesvirus saimiri strain 11 immortalizes a restricted marmoset T8 lymphocyte subpopulation in vitro. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1986;164:926–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.3.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchen S, Resch W, Yamane A, Kuo N, Li Z, Chakraborty T, Wei L, Laurence A, Yasuda T, Peng S, et al. Regulation of microRNA expression and abundance during lymphopoiesis. Immunity. 2010;32:828–839. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SI, Murthy SC, Trimble JJ, Desrosiers RC, Steitz JA. Four novel U RNAs are encoded by a herpesvirus. Cell. 1988;54:599–607. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libri V, Helwak A, Miesen P, Santhakumar D, Borger JG, Kudla G, Grey F, Tollervey D, Buck AH. Murine cytomegalovirus encodes a miR-27 inhibitor disguised as a target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:279–284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114204109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Smith ER, Takahashi H, Lai KC, Martin-Brown S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Conaway JW, Conaway RC, Shilatifard A. AFF4, a component of the ELL/P-TEFb elongation complex and a shared subunit of MLL chimeras, can link transcription elongation to leukemia. Molecular cell. 2010;37:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Juo ZS, Shim AH, Focia PJ, Chen X, Garcia KC, He X. Structural basis of semaphorin-plexin recognition and viral mimicry from Sema7A and A39R complexes with PlexinC1. Cell. 2010;142:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AM, Davis RJ. Targeting JNK for therapeutic benefit: from junk to gold? Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2003;2:554–565. doi: 10.1038/nrd1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinowski L, Tanguy M, Krmpotic A, Radle B, Lisnic VJ, Tuddenham L, Chane-Woon-Ming B, Ruzsics Z, Erhard F, Benkartek C, et al. Degradation of cellular mir-27 by a novel, highly abundant viral transcript is important for efficient virus replication in vivo. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002510. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayoral RJ, Monticelli S. Stable overexpression of miRNAs in bone marrow-derived murine mast cells using lentiviral expression vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;667:205–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-811-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M, Janeway C. Janeway’s immunobiology. 7. New York: Garland Science; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy S, Kamine J, Desrosiers RC. Viral-encoded small RNAs in herpes virus saimiri induced tumors. The EMBO journal. 1986;5:1625–1632. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy SC, Trimble JJ, Desrosiers RC. Deletion mutants of herpesvirus saimiri define an open reading frame necessary for transformation. Journal of virology. 1989;63:3307–3314. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3307-3314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myster F, Palmeira L, Vanderplasschen A, Dewals B. Investigation on the Role of the Viral Semaphorin encoded by the A3 Gene of Alcelaphine Herpesvirus 1 in the Induction of Malignant Catarrhal Fever. 36th Annual International Herpesvirus Workshop; Gdansk, Poland. 2011. http://hdl.handle.net/2268/106943. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DD, Davis WC, Brown WC, Li H, O’Toole D, Oaks JL. CD8(+)/perforin(+)/WC1(−) gammadelta T cells, not CD8(+) alphabeta T cells, infiltrate vasculitis lesions of American bison (Bison bison) with experimental sheep-associated malignant catarrhal fever. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 2010;136:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, De Planell-Saguer M, Lamprinaki S, Kiriakidou M, Zhang P, O’Doherty U, Mourelatos Z. A novel monoclonal antibody against human Argonaute proteins reveals unexpected characteristics of miRNAs in human blood cells. RNA. 2007;13:1787–1792. doi: 10.1261/rna.646007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noraz N, Saha K, Ottones F, Smith S, Taylor N. Constitutive activation of TCR signaling molecules in IL-2-independent Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:2042–2045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obad S, dos Santos CO, Petri A, Heidenblad M, Broom O, Ruse C, Fu C, Lindow M, Stenvang J, Straarup EM, et al. Silencing of microRNA families by seed-targeting tiny LNAs. Nature genetics. 2011;43:371–378. doi: 10.1038/ng.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon M, Pedraza-Alva G. JNK and p38 MAP kinases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Immunological reviews. 2003;192:131–142. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudel S, Flatley A, Weinmann L, Kremmer E, Meister G. A multifunctional human Argonaute2-specific monoclonal antibody. RNA. 2008;14:1244–1253. doi: 10.1261/rna.973808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth SA, Zaitseva L, Murray MY, Shah NM, Bowles KM, Macewan DJ. The high Nrf2 expression in human acute myeloid leukemia is driven by NF-kappaB and underlies its chemo-resistance. Blood. 2012;120:5188. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell GC, Stewart JP, Haig DM. Malignant catarrhal fever: a review. Vet J. 2009;179:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawasdikosol S. In: Detecting tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins by Western blot analysis. Current protocols in immunology. Unit 11. Coligan John E, et al., editors. Chapter 11. 2010. pp. 13pp. 11–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2004;75:163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annual review of microbiology. 2010;64:123–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. Journal of virology. 2009;83:9618–9629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steed AL, Barton ES, Tibbetts SA, Popkin DL, Lutzke ML, Rochford R, Virgin HW., 4th Gamma interferon blocks gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latency. Journal of virology. 2006;80:192–200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.192-200.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz J, Borah S, Cazalla D, Fok V, Lytle R, Mitton-Fry R, Riley K, Samji T. Noncoding RNPs of viral origin. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H. Semaphorins and their receptors in immune cell interactions. Nature immunology. 2008;9:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ni1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagnone L, Artigiani S, Chen H, He Z, Ming GI, Song H, Chedotal A, Winberg ML, Goodman CS, Poo M, et al. Plexins are a large family of receptors for transmembrane, secreted, and GPI-anchored semaphorins in vertebrates. Cell. 1999;99:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuschl T. Annealing siRNAs to produce siRNA duplexes. CSH protocols. 2006;2006 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman DA, Lee SI, Steitz JA. Nucleotide sequence of HSUR 5 RNA from herpesvirus saimiri. Nucleic acids research. 1989;17:1258. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.3.1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Darnell RB. Mapping in vivo protein-RNA interactions at single-nucleotide resolution from HITS-CLIP data. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.