Abstract

Developmental theories of borderline personality disorder (BPD) posit that transactions between child characteristics and adverse environments, especially those in the context of the parent-child relationship, shape and maintain symptoms of the disorder over time. However, very little empirical work has investigated the role of parenting and parent-child transactions that may predict BPD severity over time. We examined maternal and dyadic affective behaviors during a mother-adolescent conflict discussion task as predictors of the course of BPD severity scores across three years in a diverse, at-risk sample of girls (n=74) oversampled for affective instability, and their biological mothers. Adolescent girls completed a structured conflict discussion task with their mothers at age 16. Girls' self-reported BPD severity scores were assessed annually from ages 15-17. Mother-adolescent interactions were coded using a global rating system of maternal and dyadic affective behaviors. Results from multi-level linear mixed models indicated that positive maternal affective behavior (i.e., supportive/validating behavior, communication skills, autonomy-promoting behavior, and positive affect) and positive dyadic affective behaviors (i.e., satisfaction and positive escalation) were associated with decreases in girls' BPD severity scores over time. Dyadic negative escalation was associated with higher overall levels of BPD severity scores, but negative maternal affective behavior (i.e., negative affect, dominance, conflict, and denial) was not. These findings suggest that the mother-daughter context is an important protective factor in shaping the course of BPD severity scores during adolescence and may be valuable in assessment, intervention, and prevention efforts.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, adolescence, parenting, mother-adolescent conflict

Several etiological theories suggest that borderline personality disorder (BPD) develops from complex transactions between a child's pre-existing emotional vulnerability and adverse family environments, especially in the context of negative interpersonal exchanges between caregivers and the child (e.g., Bateman & Fonagy, 2003; Fruzzetti, Shenk, & Hoffman, 2005; Linehan, 1993). Evidence linking BPD symptoms to both child characteristics and adverse family/environmental experiences has provided general support for these theories (Bornovalova, Hicks, Iacono, & McGue, 2009; Chanen & Kaess, 2011; Cohen et al., 2008). For example, Carlson and colleagues (2009) found that family stress and experiences of abuse and neglect, as well as child-level characteristics of insecure attachment, behavior problems, and poor emotion-and self- regulation measured from infancy predicted BPD symptoms in adulthood. While these studies demonstrated that child- and family-level risk factors for BPD symptoms are recognizable early in development, they did not examine parenting or parent-child transactions in the context of BPD symptoms.

Linehan's model (1993) asserts that invalidating environments trivialize, punish, and/or intermittently reinforce the child's personal experiences and emotional expression and that this type of parenting style may contribute to the development of BPD. Studies relying on self-report measures of parenting have supported a link between negative affective parenting behaviors and BPD symptoms across development. For example, findings from the Children in the Community study indicated that ignoring, neglecting, or dismissing their child's emotions impaired the child's emotion regulation skills, which in turn, increased child suicide behaviors (Johnson et al., 2002). In addition, both harsh punishment and low levels of parental affection were associated with the development of BPD and BPD symptoms in adolescence and adulthood (Johnson, Cohen, Chen, Kasen, & Brook, 2006). Recent findings from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS; Stepp et al., in press) demonstrated the reciprocal relationship between negative parenting and BPD symptoms in adolescent girls, finding that harsh punishment, low warmth and BPD symptoms were related across adolescence. In addition to these stable, trait-like associations across adolescence, within-individual, year-to-year increases in BPD symptoms evoked more negative parenting, but the state-level changes in parenting did not predict more BPD symptoms. While these findings underscore the importance of parenting and parent-child influences on BPD symptom development and maintenance, observational ratings of parenting behaviors and dyadic behaviors have yet to be examined as predictors of within-individual changes in BPD symptoms across adolescence.

These aspects of parenting have been investigated among self-harming adolescents, a portion of whom are likely to develop BPD during later adolescence or adulthood. During a conflict discussion task, families of self-harming adolescents demonstrated less positive affect, more negative affect, and lower cohesiveness compared with a control group of adolescents who did not self-harm (Crowell et al., 2008). Family relationships characterized by a lack of support for managing emotions combined with higher levels of conflict have also been associated with adolescent emotion dysregulation and self-harm (Adrian, Zeman, Erdley, Lisa, & Sim, 2011). Yap and colleagues (Yap et al., 2011; Yap, Allen, & Ladouceur, 2008) have found that adolescents reported using more maladaptive emotion regulation strategies if their mothers reported using invalidating emotion socialization practices, such as punishing and restricting responses to their adolescents' positive emotion expressions. These types of observational ratings of parenting and dyadic affective behavior hold several strengths over traditional self-report measures in that they reduce biases associated with social desirability and memory error.

Furthermore, the potential buffering influence of positive parental affective behaviors (e.g., support, validation, satisfaction, positive affect) on BPD severity scores has yet to be explored. Drawing on literature from youth at-risk for depression, parental affective behavior is defined as the behavioral aspects of emotion that occur within the context of parenting (McMakin et al., 2011). Patterns of positive or negative parental affective behaviors may represent a pathway through which emotion dysregulation is transmitted from parents through youth (Silk et al., 2006). As part of a clinical intervention, teaching mothers of adolescents with BPD to be more validating toward their adolescent was associated with improvements in the adolescents' depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and relationship satisfaction (Fruzzetti et al., 2005), suggesting that observed positive parenting affective behaviors could also be an important factor in reducing adolescent BPD symptoms in community samples.

Consistent with the reciprocal nature of parenting and BPD symptoms in adolescent girls (Stepp et al., in press), it is critical to recognize that parental affective behaviors are likely to be both a contributing factor in the development of BPD and a response to BPD symptoms in youth. Adolescents with BPD features may behave in ways that make supportive, validating parenting quite challenging. At times, harsh or controlling parenting responses may appear to be unwittingly effective in parents' efforts to help the adolescent cope with overwhelming emotions or in response to dangerous behavior. Because of this, it is important to study parent-child transactions at a dyadic level, rather than at the individual level of the parent or adolescent. For example, a transactional escalation of negative affect, with both the mother and adolescent exacerbating each other's negative affect and behavior, creating a snowball effect, may characterize the emotional communication between adolescents who are at risk for BPD and their mothers. The opposite may also be true, that is, positive dyadic escalations characterized by building off of each other's positive emotions and offering support for one another may serve as a buffer against the development or maintenance of BPD symptoms in adolescence.

The overall goal of the current study was to investigate observed maternal and dyadic affective behaviors during a mother-adolescent conflict discussion task as predictors of the course of BPD severity scores across three years in a diverse, at-risk sample of adolescent girls and their biological mothers. Consistent with previous literature and theoretical accounts that emphasize the role of parent-child transactions in the development of BPD, we hypothesized that negative maternal and dyadic affective behaviors would be associated with increases in BPD severity scores over time. Conversely, we hypothesized that positive maternal and dyadic affective behaviors would be associated with decreases in BPD severity scores over time.

Method

Participants

Participants are girls and their biological mothers recruited from the PGS (see Hipwell et al., 2002; Keenan et al., 2010 for details on study design and recruitment), an urban community sample of four age cohorts who were ages 5, 6, 7 and 8 at the first assessment in 2000/2001. Participants in the PGS have been followed with annual interviews since that time. To identify the PGS sample, low income neighborhoods were oversampled, such that neighborhoods in which at least 25% of families were living at or below poverty level were fully enumerated and a random selection of 50% of households in all other neighborhoods were enumerated. Of the 2,875 eligible families re-contacted to determine interest in study participation, 2,451 families (85%) agreed to participate and provided informed consent.

A total of 110 16 year-old girls were selected for participation in the Personality substudy of the PGS in 2010-2012 (girls in cohort 7 in 2010, cohort 6 in 2011, and cohort 5 in 2012), with approximately one-third screening high on affective instability (scores > 11) by their self-report on the Affective Instability subscale of the Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features scale (Morey, 1991). The remainder of the sample was randomly selected from girls endorsing low levels of affective instability (scores < 11). The sampling strategy was designed to increase the base rate of affective instability, a core symptom of BPD in order to recruit a sample of girls who may be at risk for BPD. Data for the current study come from 74 adolescent girls and their mothers who received observational ratings based on their participation in the conflict discussion task. Independent samples t-tests and Chi Square analyses indicated that these 74 girls were comparable to the sample of 110 in terms of race, poverty, AI score, and BPD score (all p's >0.05). Reflecting the demographic characteristics of the PGS, the current sample was racially and socioeconomically diverse. The majority of participants identified as Black or African American (65%, n = 48) and the remaining participants identified as White or Caucasian. Forty-three percent of families reported receiving some form of public assistance in the past year (e.g., food stamps, WIC, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families).

Procedures

As part of the annual PGS interviews, girls reported on the extent of experienced BPD features annually for three consecutive years, spanning ages 15-17. As part of the Personality substudy, adolescent Axis I and II symptoms were assessed via semi-structured clinical interviews. Additionally, mothers and daughters were videotaped while completing a structured conflict discussion task. All study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Families were compensated for their participation.

Measures

BPD severity scores

BPD severity scores were assessed in three consecutive years with girls' reports at ages 15, 16, and 17 using questions from the screening questionnaire of the International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE-BOR; Loranger et al., 1994). The IPDE-BOR consists of nine items (e.g., “I get into very intense relationships that don't last”) rated either true or false (scored 1 or 0, respectively). Items were summed to yield a dimensional BPD severity score in each year. Adequate concurrent validity, and sensitivity and specificity of BPD severity scores to clinicians' diagnosis have been demonstrated for the IPDE-BOR. Further, this questionnaire has been validated for use in adolescent samples (Chanen et al., 2008; Sharp et al., 2012; Stepp, Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2011; Stepp, Pilkonis, Hipwell, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2010). In this sample, the average score during the age 16 assessment was 2.96, the median score was 3, and scores ranged from 0 to 9. The upper quartile of our sample had an average score of 4, which is in the clinically significant range (Smith, Muir, & Blackwood, 2005; Stepp, Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2011). IPDE-BOR self-reports at age 16 were moderately correlated with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SIDP-IV; Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997) dimensional scores (r's = .53-.68, p's <.001, n = 74) and symptom counts (r's = .43-.58, p's < .001, n = 74) from the substudy. Because we lacked complete SIDP-IV interview data over multiple time points, we used repeated IPDE-BOR scores at ages 15-17 in this report, which allowed us to examine maternal and dyadic affective behaviors as predictors of within-individual changes in BPD severity scores over time. During the age 16 assessment, five girls (6.8%) met full criteria for BPD according to the SIDP-IV clinical interview. Although the rate of diagnosable BPD is somewhat low, there was a high degree of variability in the presence of individual BPD symptoms, particularly affective instability (27%) and excessive anger (28%). In addition, 20% of the sample met criteria for any personality disorder based on clinical interviews, with the most frequent being borderline, antisocial, narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders.

Mother-daughter conflict discussion

Mothers and daughters were videotaped while completing a structured discussion task designed to elicit conflict and negative emotion (O'Connor, Hetherington, Reiss, & Plomin, 1995). First, mothers and daughters completed a brief questionnaire about common areas of conflict among adolescents and their mothers. This 25-item questionnaire was designed to identify common areas of conflict between mothers and adolescents (e.g., manners, chores, behavior toward parent). Responses were rated on two scales: frequency, ranked from 1 (never) to 6 (more than once per day) and intensity, ranked between 1 (not at all bad) and 5 (extremely bad). Topics were selected by trained research assistants based on the best match between the mother and adolescent on both intensity and frequency. Dyads were asked to discuss the conflict rated most highly in terms of frequency and severity by both members of the dyad during an 8-minute videotaped discussion (Furman & Shomaker, 2008; McMakin et al., 2011).

Observational coding

The Revised Interactional Dimensions Coding System (IDCS-R; Furman & Shomaker, 2008) was used to code the mother-daughter interactions. This coding system was originally designed to observationally measure couples' interactions during problem solving and was modified for use with adolescents (Furman & Shomaker, 2008). The coding team included a master reliability coder, who was trained by the developers of the coding system, and several research assistants who were trained to acceptable levels of reliability. Coders were blind to each participant's BPD severity scores and study hypotheses. Tapes were randomly assigned to each coder, who rated observable behavior, facial expressions, and the verbal content of both mothers and daughters in each interaction. The same coders rated maternal, adolescent, and dyadic behaviors. The current project focuses on the subset of IDCS-R maternal affective behavior and dyadic codes that directly pertain to our study hypotheses as predictors of the longitudinal course of girls' BPD severity scores. Mothers'affective behavior was coded based on their own individual behaviors during the task: overall positive affect, overall negative affect, denial, dominance, support-validation, conflict, communication skills, and promoting autonomy. Dyadic codes were based on ratings of the dyad's affective behavior together, using the entire interaction as the coding unit: positive escalation, negative escalation, and relationship satisfaction. Table 1 provides descriptions of all codes used in this study. The maternal affective behavior codes were subjected to factor analysis, which revealed the presence of two factors with eigenvalues greater than one and strong factor loadings: 1) a factor comprised of positive maternal behavior codes, including positive affect, support-validation, communication skills, and promoting autonomy codes (α= .87); and 2) a factor comprised of negative maternal behavior codes, including maternal negative affect, denial, dominance, and conflict codes (α= .70). Composite variables for these two factors were created based on the mean of the corresponding maternal behavior codes. Positive affective behavior included statements such as, “It sounds like you are frustrated with my rules,” and “I want to know how you feel, even if you disagree with me.” Negative affective behavior included statements such as, “I can't say anything to you,” “I am going to call you whatever name I want to call you,” or, “Get over it.”

Table 1. Definitions of Maternal and Dyadic Behavior Codes.

| Code | Rated | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Affective Behaviors | ||

| 1. Positive Affect | 1-5 rating | Positivity of facial expressions, body positioning, and emotional tone |

| 2. Negative Affect | 1-5 rating | Negativity of facial expressions, body positioning, and emotional tone |

| 3. Denial | 1-5 rating | Rejection of a problem's existence or personal responsibility |

| 4. Dominance | 1-5 rating | Achievement of control or influence over partner |

| 5. Support/Validation | 1-5 rating | Positive listening/speaking skills that demonstrate understanding |

| 6. Conflict | 1-5 rating | Expressed struggle between two people with incompatible goals |

| 7. Communication skills | 1-5 rating | Individual's ability to convey thoughts and feelings in a constructive manner |

| 8. Promoting Autonomy | 1-5 rating | Behaviors aimed at promoting a reasoned discussion of a disagreement |

| Dyadic Affective Behaviors | ||

| 1. Positive Escalation | 1-5 rating | A sequential pattern where positive behavior from one partner is followed by positive behavior from the other partner, creating a snowball effect |

| 2. Negative Escalation | 1-5 rating | A sequential pattern where negative behavior from one partner is followed by negative behavior from the other partner, creating a snowball effect |

| 3. Satisfaction | 1-5 rating | Degree to which the pair would consider themselves happy in the relationship |

Note: Behavioral codes are from the Interactional Dimensions Coding System-Revised (IDCS-R; Furman & Shomaker, 2008). Only those codes that were used in our analyses are presented here.

Participants were rated on a five-point Likert scale with half-point intervals (1= extremely uncharacteristic to 5= extremely characteristic) for each of the maternal and dyadic codes. Twenty-one percent of the tapes were coded by all members of the team and were used to calculate inter-rater agreement. Each of the coders was compared to the reliability coder. Intra-class correlations coefficients for the codes of interest ranged from .69 to .93 (M = .79; SD= .07), consistent with other research using the IDCS-R coding system (Furman & Shomaker, 2008; McMakin et al., 2011). When coders were compared to one another, intra-class coefficients for the codes of interest ranged from .61 to .93 (M=.74).

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Change in BPD severity scores was analyzed using multilevel linear mixed (MLM) models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), which included an autoregressive error structure to account for dependencies due to repeated measurements (i.e., autocorrelation). Five MLMs were conducted, one for each of the maternal composites (e.g. positve and negative) and dyadic behavior codes (e.g. negative escalation, positive escalation, and relationship satisfaction) as predictors of change in BPD severity scores over time. Fixed effects were included in each MLM for time (i.e., within-individual change over time in BPD severity scores from ages 15-17), maternal or dyadic affective behavior (mean-centered), and the interactions between time and maternal or dyadic affective behavior to examine the influence of these factors on changes in BPD severity scores over time. Since the mother-daugther conflict discussion task was completed when girls were aged 16, time was centered at this age. Thus, time was parameterized as -1, 0, and 1 corresponding to the annual assessment of BPD severity scores at ages 15, 16, and 17, respectively. Therefore, the intercept can be interpreted as the mean level of BPD severity scores at age 16, and the linear slope for time can be interpreted as the average within-individual rate of change in BPD severity scores from ages 15 to 17. All models included minority race (coded 0 = White or Caucasian, 1 = Black or African American) and family poverty (coded 1 = family received public assistance, 0 = family did not receive public assistance) as covariates. Random effects for the BPD severity score intercept were included in all models to account for individual variability in mean levels of BPD severity scores. The inclusion of random slopes for time (i.e., BPD severity score linear slope) led to model nonconvergence, even when we specified different covariance structures for the random effects (e.g., variance components, diagonal, etc.). We suspect this nonconvergence was due to the relatively small sample size and limited number of data points, which can lead to convergence problems with more complex models. We therefore included only the random intercept in all models, and used a simple variance components (VC) covariance matrix for random effects. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation was used to assess the significance of random effects. Degrees of freedom were estimated using the Satterthwaite method (Fitzmaurice, Laird, & Ware, 2004).

Results

Descriptive statistics for and bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Table 2. Before examining full conditional models that included maternal or dyadic behavior codes and their interactions with time, we first examined a MLM of average change in BPD severity scores over the three-year period after adjusting for race and poverty. Results showed a main effect for time, indicating a linear decrease in BPD severity scores across three years (B = -0.19, SE = 0.09, t = -2.08, p = .04). The random effect for intercept indicated that there was significant individual variability in average levels of BPD severity scores at age 16 (σ2 = 2.68, SE = 0.51, Wald Z = 5.29, p < .001). The fixed effects of poverty (B = 0.77, SE = 0.42, t = 1.83, p = .07) and minority race (B = .57, SE = .43, t = 1.30, p = .20) on overall level of BPD severity scores did not reach significance; however, given the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the study sample, race and poverty were retained in subsequent models as covariates in order to adjust model coefficients for these factors. Substantive interpretations of subsequent model results did not differ whether or not these covariates were included in the models.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for All Study Variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | ||||||||||

| 1. Poverty | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Race | 0.24** | 1 | ||||||||

| Maternal Affective Behaviors | ||||||||||

| 3. Positive | -0.23** | -0.13 | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Negative | 0.12 | -0.04 | -0.34** | 1 | ||||||

| Dyadic Affective Behaviors | ||||||||||

| 5. Positive Escalation | -0.10 | -0.07 | 0.63** | -0.30** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Negative Escalation | 0.04 | -0.00 | 0.05 | 0.62** | -0.12 | 1 | ||||

| 7. Satisfaction | -0.23** | -0.01 | 0.62** | -0.51** | 0.77** | -0.34** | 1 | |||

| Outcome | ||||||||||

| 8. BPD symptom severity, age 15 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.16 | -0.00 | 0.29* | -0.10 | 1 | ||

| 9. BPD symptom severity age 16 | 0.21 | 0.14 | -0.01 | 0.13 | -0.05 | 0.28* | -0.06 | 0.72** | 1 | |

| 10. BPD symptom severity age 17 | 0.29* | 0.22 | -0.20 | 0.15 | -0.24* | 0.25* | -0.27* | 0.52** | 0.72** | 1 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean/Percent | 43.2 | 64.9 | 10.46 | 9.43 | 2.02 | 2.32 | 2.76 | 3.13 | 2.96 | 2.76 |

| SD | 2.60 | 2.25 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 2.16 | 2.05 | 2.12 | ||

Notes. Poverty coded as ‘0’ no public assistance, ‘1’ receieved public assistance; Race coded as ‘0’ White, ‘1’ African American; BPD = borderline personality disorder.

p<.05;

p<.01

Maternal Affective Behaviors

Estimates of fixed effects for each MLM are presented in Tables 3-4. We examined the positive and negative maternal affective behavior composite scores as predictors of the level and course of BPD severity scores in two separate MLMs, controlling for race and poverty. The main effect for time in predicting BPD severity scores remained significant in both models, indicating a significant linear decrease in BPD severity scores across three years. Neither of the main effects of positive or negative maternal affective behaviors were statistically significant, indicating that maternal affective behaviors were not associated with girls' average level of BPD severity scores at age 16. However, the main effect for time was qualified by an interaction with positive maternal affective behaviors. Specifically, as shown in Table 3, there was a significant Time × Positive maternal affective behavior interaction in the prediction of BPD severity scores. The Time × Negative maternal affective behavior interaction was not significant, indicating that negative maternal affective behaviors did not predict changes in BPD severity scores across this three-year period (Table 3).

Table 3. Fixed Effect Estimates from the Multilevel Models Predicting Change in BPD Symptom Severity from Maternal Affective Behaviors.

| Effect | B | SE | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Positive Affective Behavior | |||||

| Intercept | 2.27 | 0.36 | 6.23 | 69.85 | <.001 |

| Poverty | 0.76 | 0.43 | 1.76 | 69.85 | .08 |

| Race | 0.56 | 0.44 | 1.28 | 69.85 | ns |

| Time | -0.19 | 0.09 | -2.14 | 78.14 | .04 |

| Maternal Positive | -0.01 | 0.08 | -0.07 | 69.86 | ns |

| Time × Maternal Positive | -0.08 | 0.03 | -2.41 | 78.14 | .02 |

| Maternal Negative Affective Behavior | |||||

| Intercept | 2.27 | 0.36 | 6.39 | 69.83 | <.001 |

| Poverty | 0.69 | 0.42 | 1.65 | 69.83 | ns |

| Race | 0.60 | 0.43 | 1.39 | 69.83 | ns |

| Time | -0.19 | 0.09 | -2.07 | 78.78 | .04 |

| Maternal Negative | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.29 | 69.83 | ns |

| Time × Maternal Negative | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.13 | 78.78 | ns |

Notes. Poverty coded as ‘0’ no public assistance, ‘1’ receieved public assistance; Race coded as ‘0’ White, ‘1’ African American.

Table 4. Fixed Effect Estimates from the Multilevel Models Predicting Change in BPD Symptom Severity from Dyadic Behaviors.

| Effect | B | SE | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyadic Negative Escalation | |||||

| Intercept | 2.27 | 0.34 | 6.66 | 69.80 | <.001 |

| Poverty | 0.72 | 0.40 | 1.81 | 69.80 | .08 |

| Race | 0.58 | 0.42 | 1.40 | 69.80 | ns |

| Time | -0.19 | 0.09 | -2.07 | 79.23 | .04 |

| Dyadic Negative Escalation | 0.64 | 0.23 | 2.80 | 69.80 | .007 |

| Time × Negative Escalation | -0.05 | 0.11 | -0.48 | 79.23 | ns |

| Dyadic Positive Escalation | |||||

| Intercept | 2.29 | 0.36 | 6.37 | 69.87 | <.001 |

| Poverty | 0.74 | 0.42 | 1.76 | 69.87 | .08 |

| Race | 0.55 | 0.44 | 1.26 | 69.87 | ns |

| Time | -0.19 | 0.09 | -2.18 | 77.70 | .03 |

| Dyadic Positive Escalation | -0.16 | 0.24 | -0.68 | 69.87 | ns |

| Time × Positive Escalation | -0.30 | 0.10 | -2.95 | 77.70 | .004 |

| Dyadic Satisfaction | |||||

| Intercept | 2.29 | .36 | 6.41 | 69.87 | <.001 |

| Poverty | 0.66 | 0.43 | 1.54 | 69.87 | ns |

| Race | 0.59 | 0.44 | 1.37 | 69.87 | ns |

| Time | -0.19 | 0.09 | -2.11 | 77.92 | .04 |

| Dyadic Satisfaction | -0.23 | 0.23 | -1.01 | 69.87 | ns |

| Time × Satisfaction | -0.20 | 0.10 | -2.00 | 77.92 | .05 |

Notes. Poverty coded as ‘0’ no public assistance, ‘1’ receieved public assistance; Race coded as ‘0’ White, ‘1’ African American.

Dyadic Affective Behaviors

Next we examined dyadic negative escalation, positive escalation, and satisfaction as predictors of the level and course of BPD severity scores in three separate MLMs, controlling for race and poverty (see Table 4). In addition to the significant main effects for time in each of the models, there was a significant main effect of dyadic negative escalation on BPD severity scores, indicating a positive association between negative escalation during conflict discussions and BPD severity scores at age 16 (Table 4). No other significant main effects of dyadic behaviors on average BPD severity score levels emerged. However, the main effect for time was qualified by interactions with positive dyadic behaviors, suggesting that girls whose conflict discussion interactions with their mothers were characterized by more dyadic positive escalation and satisfaction, showed a faster rate of decrease in BPD severity scores over time. The Time × Dyadic negative escalation interaction effect was not significant, suggesting that although dyadic negative escalation was associated with a higher overall level of BPD severity scores, it did not predict within-individual changes in BPD severity scores over time.

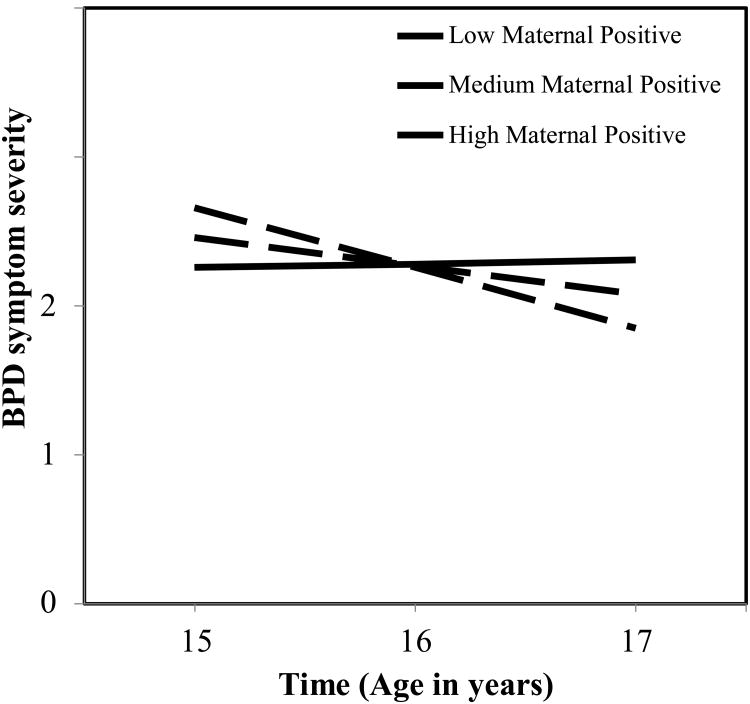

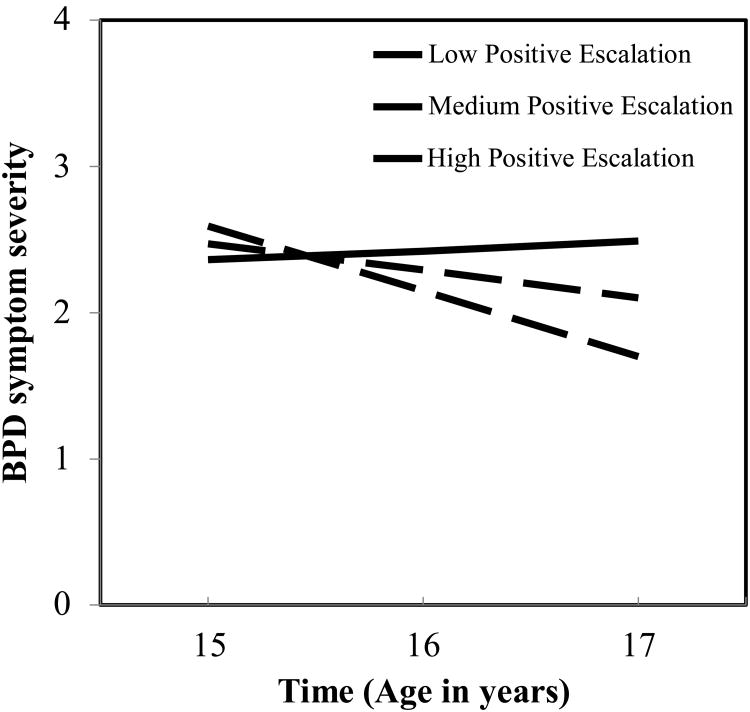

To better understand the observed interactions between time and positive maternal and dyadic affective behaviors, we plotted the model-implied trajectories of BPD severity scores at low, medium, and high levels (i.e., 1 SD below the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD above the mean) of positive maternal affective behaviors, dyadic positive escalation, and dyadic satisfaction (Figures 1-3). We also tested the significance of simple slopes at each of these designated levels of the moderators. As shown in Figures 1-3, BPD severity scores decreased at faster rates as the level of positive maternal affective behaviors, positive escalation, and satisfaction increased. In fact, the slopes at low levels of these moderators were not significantly different from zero, indicating that BPD severity scores remained stable over time when positive maternal affective behaviors and dyadic positive escalation and satisfaction were low. However, BPD severity scores decreased significantly at medium levels of these factors (p's < .05), and showed even faster rates of decrease over time at high levels of positive maternal affective behaviors, dyadic positive escalation, and dyadic satisfaction (p's ≤ .005).

Figure 1. Model-implied trajectories of girls' borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptom severity at low, medium, and high levels of positive maternal behaviors during the structured conflict discussion task.

Notes. Model-estimated intercepts were adjusted for covariates of race and poverty, and can be interpreted as the intercept when race = 0 (White or Caucasian) and poverty = 0 (no poverty).

Figure 3. Model-implied trajectories of girls' borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms at low, medium, and high levels of mother-daughter dyadic satisfaction during the structured conflict discussion task.

Notes. Model-estimated intercepts were adjusted for covariates of race and poverty, and can be interpreted as the intercept when race = 0 (White or Caucasian) and poverty = 0 (no poverty).

Discussion

The present study examined the effect of maternal and dyadic affective behaviors on the course of girls' BPD severity scores over three years in adolescence. Linking maternal and dyadic affective behaviors to stability and change in BPD severity scores during adolescence highlights several potential mechanisms of BPD development and maintenance. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the influence of observed maternal and dyadic affective behaviors on the developmental course of adolescent BPD severity scores.

When examing within-individual change in BPD severity scores, results indicated a significant linear decrease over three years (ages 15-17). This finding replicates the results of other longitudinal studies with community samples documenting that BPD severity scores peak in early adolescence and then show a pattern of decline over time (Cohen et al., 2008; Johnson, 2000). This pattern of decrease in BPD severity scores over the course of adolescence may reflect normative developmental maturation in emotion regulation, behavioral inhibition, and social skills during the adolescent period. However, the significant decrease in BPD severity scores from ages 15-17 that we observed contradicts recent reports that mean levels of BPD severity scores remain relatively stable across ages 14-17 in large community samples (Bornolova, Hicks, Iacono, & McGue, 2009), including the larger PGS study sample (Stepp et al., in press). This discrepancy may be to due to recruiting a more at-risk sample for this substudy, oversampling for participants with high levels of affective instability, rather than the larger community sample.

The effects of specific maternal and dyadic affective behaviors on the course of BPD severity scores were also examined. Results indicate that positive maternal affective behaviors were associated with a faster rate of decline in BPD severity scores across time. There may be several reasons for this association. First, positive and supportive parenting behaviors, especially during times of conflict and stress, may be important social learning processes for adolescents and modeled when the adolescent enages in interpersonal discussions (Schofield et al., 2012). Over time, these behaviors may decrease BPD severity scores, particularly those related to interpersonal sensitivity and dysfunction. Experiencing positive affect, support, and clear communication from a mother may signal to the daughter that she is worthy and capable as a social partner. This may be particularly crucial for adolescents at risk for developing BPD given the suggestion that forming a cohesive sense of identity may be linked to feelings of positive interpersonal contact and connectedness (Stanley & Siever, 2009). The lack of positive connection and acceptance from their mothers may serve to maintain or exacerbate the adolescent's BPD severity scores.

Surprisingly, negative maternal affective behaviors were not associated with BPD severity scores or change in BPD severity scores across time. Negative maternal affective behaviors may be more important earlier in development and be more strongly associated with the onset, rather than maintenance of BPD severity scores. Future research should continue to explore the role of negative maternal affective behaviors, especially using ecologically valid paradigms, in order to determine whether there are developmental periods under which these strategies might be harmful for the adolescent.

Importantly, results for the dyadic affective behaviors suggest that transactional parent-adolescent processes may be important protective mechanisms against the development of worsening BPD severity. Girls whose dyadic interactions with their mothers were characterized by more positive escalation and higher relationship satisfaction demonstrated a faster rate of decline in BPD severity scores. On the other hand, those whose interactions were low in positive escalation and satisfaction showed a pattern of stability, with no significant change in BPD severity scores over time from ages 15-17. This suggests that low levels of these positive transactional processes in the mother-daughter dyad may increase risk for the maintenance of BPD severity scores over time in adolescence, whereas, positive transactions between mother and adolescent may serve as protective factors against the development of BPD severity. Positive, supportive aspects of the mother-daughter relationship, such as relationship satisfaction, attenuated BPD severity scores over time, suggesting that both the mother and daughter play a role in the maintenance of adolescent BPD. Mothers who are able to supportively respond to their daughter's affect during a conflictual discussion may increase the dyad's overall relationship satisfaction and ability to engage in positive communication. These qualities may buffer an adolescent from the impact of early BPD severity scores, as the adolescent feels understood and supported even when the content of her discussions with her mother are negative. Girls with higher BPD severity scores likely experience more negative affect, more physiological arousal (Chanen & Kaess, 2011), and as a result may be less likely to accurately interpret and process the emotions and behavior of their mother. However, when paired with a mother who has the ability to supportively and positively respond to her the high negative affect, the dyad may be likely to have fewer relationship challenges that prevent the development or maintenance of BPD.

This is the first study that has observed parenting and dyadic affective behaviors during a structured conflict discussion between mothers and their daughters as predictors of the course of adolescent BPD severity scores. This study also measured BPD severity across three time points spanning three years and was able to model changes in BPD severity scores during a critical developmental window. Another strength of this study was the ability to examine dyadic aspects of the parent-adolescent interaction and how these may contribute to the development and maintenance of BPD severity scores in adolescence. Positive and negative aspects of the dyadic relationship are likely impacted by both partners. Perhaps during adolescence, the nature and quality of the parent-adolescent relationship is more strongly influenced by the adolescent than the parent (Stepp et al., in press). Future research should continue to investigate this possibility and incorporate additional measures of adolescent and maternal psychopathology, temperament, and attachment in order to examine the complex pathways leading to the development and maintenance of BPD severity scores across adolescence.

Despite the merits of this study, there are several limitations worthy of consideration. Although this study has strength in its longitudinal design, it began in adolescence and BPD severity scores are likely shaped and maintained within family systems early in development. BPD symptoms may have been present and developing in these girls before age 15 and may have altered parenting earlier in childhood. These findings can be only be interpreted as correlational, such that predictors at age 16 are associated with, but do not necessarily cause average rates of change in BPD severity scores between ages 15-17. A longer follow-up period with additional prospective assessments from earlier in development may yield additional information about parenting and parent-child transactions that are early risk factors for higher BPD severity scores across adolescence and adulthood. Additionally, although this study included a community sample that was highly diverse in terms of racial and socio-economic background, the adolescents who participated in this project had low to moderate features of BPD and it may be that the parenting findings may have been more pronounced in a sample diagnosed with BPD. The IPDE-BOR may not be the most ideal measure of BPD symptom severity as compared to clinical interviews and the use of clinical interviews to diagnose BPD symptoms would greatly strengthen future work. Furthermore, these findings may not generalize to the overall sample of the PGS, as we selected a subsample of girls to be higher on AI.

Another notable weakness of the current investigation is that we were not able to examine the uniqueness of parenting and dyadic affective behaviors to the development of BPD, as opposed to other types of psychopathology (Stepp et al., 2011). It is likely that positive maternal and dyadic affective behaviors contribute to the development of disorders other than BPD. Perhaps factors such as positive maternal affective behaviors are not unique to the prediction of specific diagnoses, but may be uniquely related to the development of temperament or personality traits, such as neuroticism, that may cut across several disorders. Future work using larger samples of adolescents with varying Axis I and II disorders might help elucidate the specificity of these risk factors and buffers in predicting underlying traits that may predispose individuals toward specific types of psychopathology.

Another limitation was that the assessment of BPD severity scores was conducted across time only for the adolescent and not the mother. Although maternal BPD severity scores were not included in the scope of the current project, the strong genetic linkages in BPD and BPD symptoms (Lis, Greenfield, Henry, Guilé, & Dougherty, 2007) suggest that maternal BPD or BPD symptoms may be important predictors of adolescent BPD symptoms in this sample. Moreover, maternal BPD severity scores are likely to confer risk for deleterious parenting practices (Stepp, Whalen, Pilkonis, Hipwell, & Levine, 2012). Recent work from the PGS has demonstrated that maternal BPD severity scores are associated with impaired parenting of adolescent daughters, especially in terms of psychologically controlling parenting behaviors assessed via adolescent-report (Zalewski, Scott, Whalen, Beeney, Hipwell, & Stepp, under review). Future work will assess the impact of both maternal and adolescent BPD severity scores on parenting practices and adolescent outcomes. It is also possible that maternal BPD severity scores may predict or interact with affective parenting behaviors and dyadic relationship components, exacerbating the development of adolescent BPD severity scores.

Future research should build upon the current study's findings and continue to investigate the role of parenting and mother-adolescent transactions in the development of BPD. Although this study represents an important first step, it will be crucial for future work to continue to assess parenting and parent-child transactions longitudinally and in different situations, such as during a discussion task designed to plan a fun activity or reminisce about a positive event. Since parent responses to positive emotions may differ substantially from those in response to negative ones, examining the parent-adolescent dyad across different situations could more clearly identify the dyad's strengths and weaknesses. In addition, future work could employ a positive mood induction or positive discussion task prior to the conflict discussion in order to assess the balance of positive and negative parenting behaviors and transition between contexts under these conditions. Finally, intensive repeated measures of these dyadic processes over time would be valuable for examining parent-adolescent transactional processes as they unfold in real time, which may yield valuable insights regarding effective clinical interventions for vulnerable youth and their families.

These findings highlight the importance of maternal affective behaviors and dyadic transactions in potentially reducing BPD severity scores in adolescent girls. The notion that positive, supportive communication during conflict discussions between parents and adolescents can lead to decreases in adolescent BPD severity scores is consistent with the maternal validation intervention that was associated with improvements in adolescents with BPD (Fruzzetti et al., 2005). The parent-adolescent relationship context may be a fruitful context for the focus of future clinical interventions.

In summary, positive maternal and dyadic affective behaviors, observed during a structured conflict discussion, were associated with faster rates of decline in BPD severity scores across time. Specifically, maternal communication skills, ability to promote autonomy, positive affect, and support/validation predicted a faster decrease in their daughters' BPD severity scores over the course of three years in adolescence. Furthermore, satisfaction in the dyadic relationship and positive escalation in the dyad during the conflict task predicted more rapid declines in BPD severity scores across time. These findings suggest that the mother-daughter context is an important protective factor in shaping the course of BPD severity during adolescence. The parent-adolescent relationship may also be a clinically useful context for clinical assessment, intervention, and prevention efforts. Future work should continue to use ecologically valid paradigms to determine the nature and the extent of the role of parenting and the parent-adolescent relationship in the development of BPD in adolescents.

Figure 2. Model-implied trajectories of girls' borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptom severity at low, medium, and high levels of mother-daughter dyadic positive escalation during the structured conflict discussion task.

Notes. Model-estimated intercepts were adjusted for covariates of race and poverty, and can be interpreted as the intercept when race = 0 (White or Caucasian) and poverty = 0 (no poverty).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH056630), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA012237), and by funding from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the FISA Foundation and the Falk Fund. Ms. Whalen's effort was supported by F31 MH093991. Dr. Scott's effort was supported by F32 MH097311. Dr. Stepp's effort was supported by K01 MH086713.

Contributor Information

Diana J. Whalen, University of Pittsburgh

Lori N. Scott, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Karen P. Jakubowski, University of Pittsburgh

Dana L. McMakin, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Alison E. Hipwell, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Jennifer S. Silk, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Stephanie D. Stepp, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

References

- Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Lisa L, Sim L. Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(3):389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. The development of an attachment-based treatment program for borderline personality disorder. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2003;67(3):187–211. doi: 10.1521/bumc.67.3.187.23439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Stability, change, and heritability of borderline personality disorder traits from adolescence to adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(4):1335–1353. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Egeland B, Sroufe LA. A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(4):1311–1334. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D, McDougall E, Yuen HP, Rawlings D, Jackson HJ. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. Journal of personality disorders. 2008;22(4):353–364. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, Kaess M. Developmental Pathways to Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0242-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Chen H, Gordon K, Johnson JG, Brook J, Kasen S. Socioeconomic background and the developmental course of schizotypal and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(02):633–650. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800031X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice G, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti AE, Shenk C, Hoffman PD. Family interaction and the development of borderline personality disorder: A transactional model. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(4):1007–1030. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Shomaker LB. Patterns of interaction in adolescent romantic relationships: Distinct features and links to other close relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(6):771–788. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, Kroneman L. Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2002;12(1):99–118. doi: 10.1002/cbm.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG. Adolescent personality disorders associated with violence and criminal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(9):1406–1412. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Chen H, Kasen S, Brook JS. Parenting behaviors associated with risk for offspring personality disorder during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):579–587. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):741–749. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Hipwell A, Chung T, Stepp S, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, McTigue K. The Pittsburgh Girls Study: Overview and initial findings. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(4):506–521. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lis E, Greenfield B, Henry M, Guilé JM, Dougherty G. Neuroimaging and genetics of borderline personality disorder: a review. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2007;32(3):162–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, Berger P, Buchheim P, Channabasavanna SM, et al. Ferguson B. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):215–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMakin DL, Burkhouse KL, Olino TM, Siegle GJ, Dahl RE, Silk JS. Affective functioning among early adolescents at high and low familial risk for depression and their mothers: A focus on individual and transactional processes across contexts. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(8):1213–1225. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9540-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. The Personality Assessment Inventory Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG, Hetherington EM, Reiss D, Plomin R. A twin-sibling study of observed parent-adolescent interactions. Child Development. 1995;66(3):812–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Conger RD, Donnellan MB, Jochem R, Widaman KF, Conger KJ. Merrill-Palmer quarterly. 2. Vol. 58. Wayne State University: Press; 2012. Parent personality and positive parenting as predictors of positive adolescent personality development over time; pp. 255–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Green KL, Yaroslavsky I, Venta A, Zanarini MC, Pettit J. The incremental validity of borderline personality disorder relative to major depressive disorder for suicidal ideation and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Journal of personality disorders. 2012;26(6):927–938. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Lane TL, Kovacs M. Maternal depression and child internalizing: the moderating role of child emotion regulation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):116–126. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Muir WJ, Blackwood DHR. Borderline personality disorder characteristics in young adults with recurrent mood disorders: A comparison of bipolar and unipolar depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;87(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Siever LJ. The interpersonal dimension of borderline personality disorder: Toward a neuropeptide model. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;167(1):24–39. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Trajectories of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms as precursors of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Whalen DJ, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, Levine MD. Parenting behaviors of mothers with borderline personality disorder: A call to action. Children of mothers with borderline personality disorder: Identifying parenting behaviors as potential targets for intervention. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3(1):76–91. doi: 10.1037/a0023081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Whalen DJ, Scott LN, Zalewski M, Loeber R, Hipwell AE. Reciprocal effects of parenting and borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. Development and Psycholopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413001041. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Allen NB, Ladouceur CD. Maternal Socialization of Positive Affect: The Impact of Invalidation on Adolescent Emotion Regulation and Depressive Symptomatology. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Allen NB, O'Shea M, di Parsia P, Simmons JG, Sheeber L. Early adolescents' temperament, emotion regulation during mother-child interactions, and depressive symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):267–282. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewski M, Scott LN, Whalen DJ, Beeny J, Hipwell AE, Stepp SD. Parental borderline personality disorder symptoms and parenting of adolescent girls. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_131. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]