Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to analyze the scientific literature about social networks and social support in eating disorders (ED).

Methods

By combining keywords, an integrative review was performed. It included publications from 2006–2013, retrieved from the MEDLINE, LILACS, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases. The selection of articles was based on preestablished inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

A total of 24 articles were selected for data extraction. There was a predominance of studies that used nonexperimental and descriptive designs, and which were published in international journals. This review provided evidence of the fact that fully consolidated literature regarding social support and social networks in patients with ED is not available, given the small number of studies dedicated to the subject. We identified evidence that the family social network of patients with ED has been widely explored by the literature, although there is a lack of studies about other networks and sources of social support outside the family.

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this study shows the need to include other social networks in health care. This expansion beyond family networks would include significant others – such as friends, colleagues, neighbors, people from religious groups, among others – who could help the individual coping with the disorder. The study also highlights the need for future research on this topic, as well as a need for greater investment in publications on the various dimensions of social support and social networks.

Keywords: eating disorders, social networks, social support, family relations, peer relations

Introduction

Interest in issues of social networks and social support has increased considerably, especially regarding the impact of these issues on health.1 Social networks are defined as the set of people with whom we interact on a regular basis, and such interaction enables the development of our identity. It is through social networks that social support can be provided, and this refers to mutual aid that can be significant or not, depending on the degree of network integration.1 It is considered that the experience of healthy social relationships support the willingness to meet challenges of life, to fight for one’s rights, and to implement viable projects within one’s personal conditions.2 The perception of well-being, reduced malaise, longevity, and life satisfaction also seem to be supported by the provision of social support.3,4

For the last 30 years, a tradition in nursing literature has been established regarding the involvement of families in nursing care.5 A few terms have been developed, such as family-centered care, family nursing, interview with family, and others. These terms highlight the emergence of a new language that aims to communicate about family involvement in health care.5 Along with the inclusion of family, in the last decade, there has been growing scientific literature that deals with the investigation of chronic health conditions, focusing on social networks and/or social support.1

Social support has been considered an important part of health promotion, as it provides assistance to an individual’s physical and emotional needs, and it also helps mitigate the effects that stressors have on one’s quality of life.1 Sluzki4 proposes that social networks contribute to the individual to be recognized as such and to develop their self-image. By developing a sense of identity, well-being, competence, and authorship, the individual may also be responsible for becoming more actively involved in their health care and in adapting to crisis situations.4

The available literature in the field of eating disorders (EDs) encompasses fewer studies than other mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. However, significant contributions have been offered, suggesting that the perception of poor social support from family and friend networks can be considered as a predisposing factor for the development of negative feelings about one’s own body.6 These feelings seem to be related to an individual’s belief that one would receive greater social acceptance with weight loss.6

Sluzki4 suggests that people’s health is directly related to the establishment of an active social network that is stable and reliable. The absence of this type of social relation can be considered as a risk factor for the development of diseases.4 In general, the concept of social networks provides an understanding of the constitution of an individual’s identity from his or her experiences in those networks. In other words, our identity is formed by regular interactions with people with whom we speak and interact with on a daily basis. These relationships foster an individual’s social and emotional development, as well as the assignment of meaning to everyday experiences.2,4

Women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (AN) often show traits of insecurity, perfectionism, obsessiveness, inferiority, withdrawal, and avoidant behaviors.7,8 Women with bulimia nervosa, in contrast, present with several maladaptive thoughts and emotions, low self-esteem, “all or nothing” type of thinking, among others.7,9 Such psychological characteristics imply an inability to develop healthy social networks, since these women have difficulties in interpersonal relationships and are not socially well adjusted.6

Since birth, individuals establish numerous emotional bonds through regular interaction with people of their social networks. These interactions are crucial to the quality of life of people in general.2,4,6 Based on the hypothesis that women with ED present with difficulties in establishing and maintaining interpersonal and affective relationships,7,8,10 it is postulated that these difficulties may be related to the predisposition, perpetuation, and/or maintenance of the ED’s symptoms.

In this context, the present study aimed to synthesize the national and international scientific literature on social support and social networks in ED in order to clarify their connections. We sought to show the number of published studies on the subject in question, and the profile of studies indexed in scientific journals, identifying their limits and possibilities, which will enable the greater targeting of research on this topic. It is believed that the present study will offer scientific subsidies for professionals, by using other sources of support available in a patient’s social networks, aiming to improve health care.

The review question, devised based on the Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, and Outcomes strategy11 was: considering that the perception of positive social support is crucial to coping with chronic disorders,1 what is the role of social support and social networks on the course of ED? In other words, how do ED affect, and how can they be affected by, social networks and social support? The following hypothesis is considered: due to the difficulties that women with ED present in establishing and maintaining social relationships, their social networks are very limited and are restricted to family bonds. It is also hypothesized that these women perceive their social supports as weak and impaired, thus intensifying the chronicity of the disorder.

Methods

An integrative review of the literature was performed. Integrative reviews are regarded as research methods that use secondary data, where several studies that approach the same subject are gathered and analyzed, leading to the generation of general conclusions.12,13 Such methods summarize the literature pertaining to a clinical problem or phenomenon of interest, incorporate multiple perspectives, and combine data from both theoretical and empirical literature. It can also include studies with different research designs, in order to outline a synthesis of results according to a predetermined and explicit method.14

The review strategy involved the following steps:15,16 1) carry out a systematic survey of national and international publications on ED, social networks, and social support; 2) identify the authors, types of studies, years of publication, journals in which these studies were published, the origin of the articles, which language they were written in, the goals of the study, and the obtained results; and 3) conduct a descriptive analysis of the studies’ findings and provide a critical evaluation of the contributions offered for the production of knowledge on the subject.

Four databases were chosen as the sources for this study: MEDLINE (United States National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA); LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information, São Paulo, Brazil); PsycINFO (psychological abstracts; American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA); and CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EBSCO Industries, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). The search was performed using different combinations of the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS): eating disorders; social support; family relations; and social networks – both in English and in Portuguese. The descriptors were combined using the Boolean operator “AND”.17 A total of 620 studies were found. Abstracts were read and analyzed according to preset inclusion/exclusion criteria, which will be described below.

The following inclusion criteria were considered as search parameters: 1) articles that addressed social networks and social support in the context of ED; 2) articles written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish; 3) articles published between 2006 and 2013, since the purpose of the integrative review is to outline the scientific production about a specific topic of research; 4) articles that presented empirical results; 5) original articles with full text available in CAPES (Higher Education Co-ordination Agency) Journal Portal, a virtual library linked to Brazil’s Ministry of Education.43,44

As the exclusion criteria, the following limits were established: 1) literature presented in the format of a dissertation, thesis, book, book chapter, editorial, comment or critique, proceedings, and scientific reports. Despite the fact that these types of works hold great scientific value, they were not subjected to the critical scrutiny of a rigorous peer review procedure, which ensures the quality of the article and its scientific assessment. To limit the search only to articles that were subjected to a rigorous evaluation process, 2) articles on the eating behaviors of specific populations (for example, athletes, dancers, models, students, and others) were also excluded. Even though these populations are at high risk for developing ED, the excluded articles addressed subjects who had no preestablished diagnosis of the psychopathology, which could lead to bias in the data analysis. Other types of articles that were excluded were: 3) articles that addressed questions about eating behavior related to other disorders (for example, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, among others); 4) test validations and validations of other standardized instruments; 5) studies that were strongly related to the medical field (neurobiology of body image, for example); and 6) literature reviews.

Aiming to define the eligibility of each study, the data extraction was undertaken by two reviewers. Initially, the principal reviewer extracted the data from all of the studies selected. Next, the studies were distributed among three reviewers, who acted as independent validators.18 The decision made regarding the relevance of selected articles depended on the scientific clarity and consistency with which the data referring to the methodology, participants, and results were described in the content of each text. The level of interjudge concordance was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

Subsequently, the data analysis was performed taking into account the studies’ objectives, methodological designs, participants, instruments used, and the main results. Evidence from the empirical studies was summarized narratively and divided into four thematic categories according to common objectives.18 To classify the type of methodological design used in the studies, we used the criteria proposed by Polit et al.19

Results

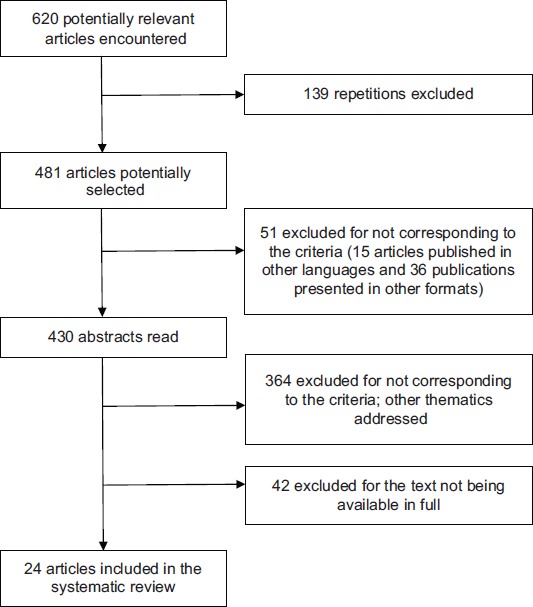

The initial search resulted in 620 articles. Repeated articles that used various combinations of descriptors and databases were discarded (Figure 1). In total, 139 repetitions were excluded, and 481 articles remained. From these, the following were excluded: 15 articles due to their publication in languages not allowed by the inclusion criteria (seven German, three French, three Italian, and one Turkish article); 36 publications in other formats (dissertations, book chapters, reviews, and editorials); 364 that did not deal with the delimited topic (articles that referred to specific pathologies such as cancer, diabetes, and other medical conditions that can trigger ED as secondary symptoms; research on the prevalence and treatment of these diseases; the development and validation of tests and scales; samples composed of individuals with clinical obesity; alternative forms of treatment for patients with ED; and others); and 42 articles that did not provide access to the entire text.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of bibliographic search results based on the PRISMA statement guidelines.

Thus, 24 articles were included in the integrative review. The interjudge concordance level was 0.95.

With regard to the sources of the published studies, there was a predominance of international journals, especially those from the United States (number [n]=11). Part of the articles retrieved in full corresponded to empirical nonexperimental studies that used descriptive and correlational methods (n=7), as well as exploratory and descriptive studies that adopted a qualitative approach to the research (n=6), and experimental studies (n=5). It is also noted an important part of nonexperimental and descriptive studies (n=4). Only one article presented a multiple case study.20

The investigated population included: adolescent girls and adult women with symptoms of ED, as determined by the application of tests and scales; caregivers and/or family members of patients with ED; members of online forums that pertain to ED; college students with symptoms of ED; and control groups that included women and/or adolescents without ED. Three studies examined the contents of websites that were pro-ED.21–23 In empirical studies, a substantial range in the variation of clinical samples was noted, as the number of participants ranged from four20 to 1,094.24

Finally, in relation to the instruments used, most studies used standardized scales to evaluate the research topic. Despite the diversity of scales used as research tools, the Eating Disorders Inventory (n=4)6,24–26 and the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (n=5)27–31 were the most frequently used. Only one article used semistructured interviews, and four studies collected sociodemographic data together with the application of assessment tools. These data can best be seen in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, where the articles were presented according to categories of convergent themes. These categories will be discussed next.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies that addressed “family as a source of social support” according to the authors, year of publication, participants, study design, objectives, and instruments (n=14)

| Authors (year) | Participants | Study design | Objectives | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimitropoulos et al39 (2013) | 26 patients paired with their siblings, recruited from an ED program | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | 1) To identify perceptions of patients with AN and their siblings regarding differential experiences within and external to the family including sibling interactions, parental treatment, relationships with peers and events that are unique to each sibling; 2) to compare how patients and their siblings perceive ED symptoms, parental affection/control, social support, and stigma; 3) to test the difference between the perception of patients with AN and their siblings about the association between family functioning and symptoms of AN. | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, Sibling Inventory of Differential Experience, Devaluation of Consumers and Consumer Families Scales, SPS, Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale, and McMaster FAD-GFS. |

| Linville et al36 (2012) | 22 women between the ages of 23–55 years who were recovered from ED | Exploratory, descriptive | To examine how social supports were helpful and hurtful during the ED recovery process and to learn about varying experiences with social supports from the perspectives of recovered women. | Semistructured interviews that lasted between 60 minutes and 90 minutes; ten were conducted in person, and 12 were conducted over Skype (Skype Technologies S.A., Luxembourg, Luxembourg) via computer. |

| Campos et al37 (2012) | Groups of family members of patients with ED | Exploratory, descriptive | To expand upon knowledge about the mother–daughter relationship in AN, with a focus on developing a conceptual framework that is able to improve the treatment of the disorder, reduce factors that perpetuate it, and improve prognosis. | A clinical method, anchored with psychodynamic references, was employed in a group of family members of patients with ED. The group met weekly, and the sessions were led by psychologists from the ED outpatient clinic of a university hospital. |

| Fitzsimmons and Bardone-Cone28 (2011) | 96 females seen at one point for an ED, including 53 with a current ED diagnosis and 43 who were at varying levels of recovery | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To examine two possible moderating factors that have the ability to potentially attenuate anxiety’s effect on an ED: coping skills and social support. | Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV, Patient Edition, Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait Anxiety Scale, Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and Eating Attitudes Test-26. |

| Rothschild-Yakar et al26 (2010) | Female adolescents with AN (n=34) and non-ED controls (n=35) | Experimental | To compare the mental abilities of women with AN and women without ED; to compare the perception of women with and without AN about the quality of their relationship with their parents; to assess whether the mental capacity and quality of relationships with parents may serve as potential predictors for the development of ED. | The Reflective Function Scale, Social Cognition and Object Relation Scale, Quality of Present Interpersonal Relationships, and two subscales of the EDI: Drive for Thinness and Bulimia. |

| Limbert6 (2010) | Women aged between 18–35 years old (n=132) | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To investigate the relationship between social support and ED symptomatology among a female, nonclinical population. | Sociodemographic questionnaire and a scale of 36 questions to assess social support, based on the Student Social Support Scale. The scale also included 64 questions taken from the EDI. |

| Gillet et al34 (2009) | 102 families (51 families with a member with ED and 51 control families) | Experimental | To compare implicit family process rules (specifically rules pertaining to kindness; expressiveness and connection; constraining thoughts, feelings, and self; inappropriate caretaking; and monitoring) in families with a young adult female diagnosed with ED and families with a young adult female without an ED diagnosis. | Sociodemographic questionnaire, Family Implicit Rules Profile, Family Substance Abuse Profile, Children of Alcoholics Screening Test, Adolescent Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory-2, Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory-3, and six questions about ED. |

| Marcos and Cantero3 | 98 female ED patients, with ages between 12–34 years old | Nonexperimental, descriptive | To assess social support dimensions (providers, satisfaction and different support actions) in patients with ED, while looking at diagnosis, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and self-concepts. | Sociodemographic and clinical questionnaire, perceived social support scale and self concept questionnaire. |

| Cunha et al32 (2009) | 34 women with an ED diagnosis and 34 controls | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To explore the differences in perceived family characteristics between a group of female patients with AN and females without an eating pathology. | Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale, Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale, Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment, and Family Beliefs Questionnaire. |

| Cooley et al25 (2008) | 91 pairs of mothers and their college-aged daughters | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To examine the effects of maternal eating behaviors and attitudes, maternal feedback to daughters about the daughters’ weight issues, mother–daughter relationship closeness, media influences, and mothers’ perceptions of their daughters’ shape on the daughters’ body image and eating pathology. | Two subscales of the EDI were used: the Composite Eating Pathology Scale and the Weight Concerns Scale. In addition, Body Image Silhouettes, Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance Questionnaire-Revised: Female Version. |

| Dimitropoulos et al38 (2008) | 63 caregivers (parents, partners, and/or siblings) of patients with AN | Experimental | To determine influences on caregiver distress and family functioning in AN using the stress process model. | The Burden Assessment Scale, Family Conflict Scales, the Devaluation of Consumers and the Devaluation of Consumer Families Scales, the SPS, the Professional Support Instrument, the FAD-GFS, and the GHQ. |

| Dallos and Denford20 (2008) | n=16, four of which were the members of four families (a daughter with AN, parents, and a sibling). | Multiple case study | To explore the experiences of four families, each of which contained a young person who had suffered with AN. The focus of the study included an exploration of the current relationships in the family, transgenerational patterns of relating within the family, and the role of food with respect to comfort. | Semistructured interviews were conducted, which drew upon aspects of the Adult Attachment Interview, including questions regarding early family experiences, family relationships, the provision of comfort, as well as losses, traumas, and integrative questions. |

| Winn et al33 (2007) | 112 caregivers and 68 adolescents with BN or ED not otherwise specified | Nonexperimental, descriptive | To explore levels of mental health problems in caregivers, to assess whether a negative experience of caregiving predicts a caregiver’s mental health status, and to determine which factors predict a negative experience of caregiving. | GHQ-12, Experience of Caregiving Inventory, Level of Expressed Emotion, Self-report Family Inventory, and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. |

| Hillege et al35 (2006) | 19 mothers and three fathers of adolescents with ED | Exploratory, descriptive | To consider the impact that an ED had on the family, particularly on the parents, as well as to give parents a voice to develop new understandings of their experiences, leading to more appropriate clinical decision making. | Semistructured interviews. Themes were identified through an in-depth analysis. |

Abbreviations: n, number; AN, anorexia nervosa; ED, eating disorder; SPS, Social Provision Scale; FAD, Family Assessment Device; GFS, General Functioning Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; EDI, Eating Disorders Inventory; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; BN, bulimia nervosa.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies that addressed “peer relations” according to the authors, year of publication, participants, study design, objectives, and instruments (n=3)

| Authors (year) | Participants | Study design | Objectives | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shomaker and Furman31 (2009) | 199 adolescents (49.75% females), their mothers, and friends | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To investigate interpersonal influences on changes in late adolescent boys’ and girls’ symptoms of disordered eating over 1 year. | Sociodemographic questionnaire, Pressure to be Physically Attractive Questionnaire, Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale, Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Body Parts Scale, and Eating Attitudes Test-26. |

| Hutchinson and Rapee24 (2007) | 1,094 female students with a mean age of 12.3 years old | Nonexperimental, descriptive, correlational | To examine the role of friendship networks and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraints, extreme weight loss behaviors, and binge eating in a large community sample of young adolescent females. | Sociodemographic questionnaire, Body Attitudes Questionnaire, Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire – Revised, and the Bulimia subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory. Data collected from friends’ networks were analyzed by a statistical program (UCINET VI). |

| Campos et al37 (2012) | Groups of family members of patients with ED | Exploratory, descriptive | To expand upon the knowledge about the mother–daughter relationship in AN, with a focus on developing a conceptual framework that is able to improve the treatment of the disorder, reduce factors that perpetuate it, and improve the patient’s prognosis. | Clinical method based on psychodynamic references, was employed in a group of family members of patients with ED. The group met weekly, and sessions were led by psychologists from the ED outpatient clinic of a university hospital. |

Abbreviations: n, number; ED, eating disorder.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies that addressed “websites and online forums” according to the authors, year of publication, participants, study design, objectives, and instruments (n=6)

| Authors (year) | Participants | Study design | Objectives | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodgers et al41 (2012) | 30 female members of online pro-ana communities; mean age was 17.4 years | Exploratory, descriptive | To explore individuals’ motivations to become a member of a French-language “pro-AN” online community, their perceptions of support provided by other members of the site, and the nature of the information provided. | EAT-40 and a Pro-ED online community questionnaire developed by the authors. |

| Borzekowski et al21 (2010) | 180 websites pro-ED | Nonexperimental, descriptive | To examine the features of pro-ED websites that describe, endorse, and support these disorders, and the messages to which users may be exposed. | Systematic content analysis of 180 active websites noting site logistics, site accessories, ‘‘thinspiration’’ material (images and prose intended to inspire weight loss), tips and tricks, recovery, themes, and perceived harm. |

| Ransom et al29 (2010) | A survey of 60 forum members and 64 age-matched university controls | Experimental | To explore the positive and negative behaviors encouraged on online forums about ED by comparing forum members’ perceptions of support received from online and offline relationships to the support received by age-matched controls in their relationships. | Assessment of body mass index and ED symptoms by the EAT-26. Then, information was collected about the clinical diagnosis, history of treatment, the specific behaviors of ED, the use of online forums, and the social support received by the online forums, and the support received from people with whom participants interact personally. |

| Csipke and Horne27 (2007) | 78 users of pro-ED websites | Nonexperimental, descriptive | To investigate characteristics of users of pro-ED websites and the perceived impact of the visits. | A 24-item questionnaire supplemented with the EAT-26 was developed and posted on the website of the UK mental health charity institution to which the authors are linked. The questionnaire was also posted on the ED website and on two pro-ED websites. |

| Brotsky and Giles22 (2007) | 12 websites pro-AN | Exploratory, descriptive | To investigate the kind of psychological support offered by pro-AN websites. Also, to comprehend website member’s beliefs towards ED, treatment and recovery. | Covert participation and thematic analysis of the topics, concerns, beliefs, and contributions of website users. |

| Mulveen and Hepworth23 (2006) | 15 websites pro-AN | Exploratory, descriptive | To examine the meaning of participation in a pro-AN website and its relationship with disordered eating. | Interpretative phenomenological analysis of 15 separate message “threads” were observed over a 6-week period. |

Abbreviations: n, number; EAT, Eating Attitudes Test; ED, eating disorder; AN, anorexia nervosa.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the study that addressed “spiritual support” according to the authors, year of publication, participants, study design, objectives, and instruments (n=1)

| Authors (year) | Participants | Study design | Objectives | Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richards et al30 (2006) | 122 women receiving inpatient ED treatment | Experimental | To evaluate the effectiveness of a spiritual group intervention for ED inpatients. | Eating Attitudes Test-26, Body Shape Questionnaire, Outcome Questionnaire-45, Multidimensional Self-Esteem Inventory, and Spiritual Well-Being Scale. |

Abbreviations: n, number; ED, eating disorder.

Discussion

The results presented by the articles were divided into four categories, which were prepared according to the following themes: 1) family as a source of social support; 2) peer relations; 3) websites and online forums; and 4) spiritual support.

Family as a source of social support

Most of the reviewed articles (n=14) addressed family matters and their relation to the ED. The results converged with respect to the characteristics of family functioning when there is a member affected by an ED; family relationships are marked by conflicts, feelings of loss, guilt, and sacrifice. Regarding the family’s perspective, there was one study that showed that family relationships are developed upon a false or frail basis, marked by a predominance of troubled ties, with frequent discussions and triangulation, discomfort and a negative relationship with food.20 The results of this study suggest that the experiences of conflicting relationships and confused communication patterns were common to all members of the investigated families. Within the four families that constituted the study sample, the adolescents with AN seemed to play a crucial role in the attempts of parents to correct the negative experiences of their own childhoods.

Compared with adolescents without this clinical condition, and with those who had disorders other than ED, girls affected by ED realize that their families are less emotionally involved. This suggests that these girls’ ability to take actions that facilitate the management of stressful events in their lives is jeopardized.32 The perception that these adolescents have of their families as being emotionally distant and unable to cope with the stress resulting from the ED seems to lead to difficulties in establishing trust in relationships with family and peers, compromising displays of affection, attachment, and also communication.32 Another study showed that negative experiences related to care were associated with the mental health of caregivers, which appears to be significantly compromised.33 The chronicity of a daughter’s ED seems to require a very high number of hours of dedication on the part of the family, which eventually causes an emotional overload that jeopardizes the mental health of caregivers, and hence affects their ability to provide appropriate care.

In addition, families with a member with ED seem to be governed by a higher proportion of restrictive rules than families who had no members with this disorder.34 The authors suggest that adolescents with ED perceive that their parents tend to restrict their behavior, hampering dialogue and the expression of affectionate feelings, which results in restrictive thoughts and feelings, and little emotional expressiveness by the daughters. Thus, the excessive constraint exerted by parents prevents daughters from having a social life and from maintaining relationships with people outside the family circle, which restricts the size of the daughters’ social networks and constrains the process of individuation.

Still concerning the perception of women with ED regarding their relationship with their family and quality of life, some authors compared this perception with that of women without ED.26 It was noted that a healthy relationship with the mother was related to a reduced desire to lose weight and lower scores on the bulimia subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory. A healthy relationship with the father, in contrast, was related to lower scores, but only on the drive for thinness subscale (ie, the healthier the father–daughter relationship, the lower the desire to lose weight).26 The findings corroborate the hypothesis that the occurrence of ED is related to the dynamics of the relationship between the affected daughter and her parents.

The family influences the onset and maintenance of ED, but the opposite is also true: these disorders can influence family dynamics, creating a feedback loop.35 These authors cite the following as major effects of ED on the family: reunion or family disintegration; parents’ failure to cope with difficulties; family’s social isolation – resulting from social stigma; and negative financial impact, which can cause strain on caregivers. It was concluded that one way to improve parents’ and families’ quality of life would be to encourage greater participation and integration of family members in ED treatment. For this to be viable, health professionals should recognize the family as a potential resource to be incorporated into strategies for an intervention. The study also documented a family’s difficulties, and highlighted the disregard that exists on the part of health professionals about the role of family in the treatment of ED.

Regarding the relationship between the symptoms of ED and the patient’s satisfaction with social support received through social networks, the literature reviewed shows variations. Most studies point to the crucial importance of family and social support for the improvement of patient’s symptoms, contributing to develop a positive self-concept and thus strengthen their self-esteem. These are necessary components for a favorable outcome of the ED. However, some studies show conflicting results regarding perceived support. Next, such contradictions will be presented and discussed.

Family support emerged as the main type of social support. In fact, most of the articles selected in the present review sought to explore the experience of families with a member affected by an ED. One study aimed to assess the dimensions of social support and check who are the people providing that support, the degree of satisfaction with perceived support and the various support actions in the context of patients with ED.3 Findings have shown that women with ED perceive their family – especially mothers and partners – as the most important source of social support. These women reported they were satisfied with the support received.

One of the selected articles indicated that support systems, such as health professionals, family, and friends, positively influenced a patient’s recovery process from the ED.36 Participants reported wishing to be noticed by their social support networks, and that they would not ignore or minimize their symptoms. Furthermore, factors that participants considered helpful to recovery were centered in approaching the ED and not avoiding or denying it. In fact, they described that their key relationships, especially with their family members, are what motivated them towards recovery.

Considering that mother–daughter relationships form the basis of AN and configure a patient’s main source of social support, some authors aimed to analyze the experience of mothers who looked after their daughters with AN.37 The authors identified frequent characteristics among the mothers that configure a particular psychic structure and influence the daughter’s pathology, such as: excessive and restrictive control, interchange between feelings of omnipotence and impotence, conflicting feelings of devotion, passion and annihilation. Including family in treatment is indispensable due to the need to minimize mother’s control over her daughter, since such control keeps both patients and family imprisoned in a rigidily consolidated dynamic. Such dynamics impoverish the social support provided by a family network.

Furthermore, an article showed that the main characteristics of family functioning in women with AN were: emotional overload; conflicts regarding the disorder and the role of the caregiver; negative attitudes and actions of other members of the family in relation to the person with AN; family stigma in relation to the affected individual; and, as a counterpoint, the provision of social support.38 The studies mentioned earlier show similar results regarding the characterization of the family as the main source of social support, despite the presence of frequent conflicts.3,36–38

Another study sought to examine the differential factors between individuals with AN and their siblings.39 Results showed that individuals with AN and their siblings did not report any significant differences in terms of maternal and paternal affection and control. However, in contrast to their siblings, patients perceived themselves as having lower levels of social support. The authors discuss these results as being due to impaired social cognition, which explains that individuals with ED perceive less social support through their inability to accurately process social stimuli.39 It is also possible that caregivers and siblings attempt to provide support, which is misinterpreted or rejected by the patient because of their impaired social cognition and, in turn, the quality and quantity of social support may diminish over time.

In contrast to two mentioned studies,3,36 which suggest that women with ED feel satisfied with the support received from a family network, one article showed that there is a relationship between the symptoms of ED and low satisfaction with the social support received from the family network.6 It is noteworthy that this study was conducted with women with symptoms of ED, the findings were assessed by scales, but there was not a preestablished medical diagnosis. The author suggests that these women, even if they share some similar characteristics, do not show similar patterns of social support when compared to individuals with ED. Therefore, new research is recommended to prove the validity of these findings.

There was a study that showed similar results.28 The authors sought to examine whether social support can be characterized as a moderating factor between anxiety and ED. Contrary to the author’s hypothesis, perceived social support – along with other factors, such as task-oriented coping and avoidance-oriented coping – did not emerge as a moderator of the relationship between trait anxiety and eating pathology.28 However, the authors point out that social support can be more important in younger individuals, especially in moments of transition. Also, social support is an important construct that can be examined in future work, as it may be unclear at times due to the complex nature of relationships.

From the data presented, the scientific literature presents gaps and inconsistencies regarding the relationship between the symptoms of ED and one’s (dis)satisfaction with received social support. Studies addressing this issue offer discrepant results, especially in relation to the perceptions and levels of satisfaction that women with ED manifest in relation to family support.3,6,28 Accordingly, this review points to the need to develop further research in this area in order to establish conclusive results, favoring the consolidation of a more consistent scientific literature. Also, the review demonstrates the importance of having health professionals value family ties, seeking them to strengthen a family’s social network and, hence, promoting a patient’s well-being.

Peer relations

Only three of the selected articles addressed the other social networks of individuals with ED, beyond the family network. One of them sought to investigate, during 1 year, the interpersonal influences on the symptoms of ED among girls and boys who were experiencing late adolescence.31 The results revealed that interpersonal pressures to be thin – from peers and family – and criticism regarding one’s appearance were factors that predisposed an individual to an increased frequency of dysfunctional eating behaviors over time. The findings of this study reinforce the significant influence of interpersonal relationships on the occurrence of ED in late adolescence, for both boys and girls.

Criticism and derogatory comments about body weight were approached by two studies.24,40 One of them indicated the existence of a specific relationship between the experiences of bullying, the teasing of classmates about physical appearance, and body dissatisfaction.40 The other study suggested that derogatory comments, negative feedback, and pressure from parents or from significant people in one’s social network regarding that individual’s body, and the need for weight loss by other female adolescents, were important factors in triggering ED.24 These data show how experiences within social networks can be painful for some individuals, and these individuals end up directing their frustrations and dissatisfactions to their own bodies. Furthermore, aversive, continuous contact with people in the environment appears to result in a defensive distancing of people in their environment. As a consequence, there is a decrease in the number of members in one’s social networks, so that the individual is restricted to a social network consisting of only a few family members.

Websites and online forums

Besides the social networks of family and friends, websites and online forums have also been investigated by some studies (n=6), and they have been characterized by users as potential sources of social support.22,23,27 Generally, these sites seem to set up a space where teenagers with ED feel that they can talk freely about their needs and difficulties.23 Although these teenagers sometimes receive hostile reactions from some users of the sites, they feel supported by most.22 Moreover, the support received in pro-ED sites was considered more significant than the support received by one’s family and other personal networks.29

Some authors noted that some of these sites – which have been appointed as pro-ED sites (ie, in favor of the ED) – exhibit graphic materials and interactive features that encourage, support, and motivate users to continue their anorexic and bulimic behaviors.21 Such features include: providing images of emaciated models; encouraging the daily counting of food and calories; and offering dieting tips.21 The common themes discussed on the websites were success, control, perfection, and solidarity. Furthermore, the authors also noted that only 38% of these sites contained information or links to guide in the individual’s recovery.

One of the selected studies identified four main topics discussed at these sites:23 1) tips and techniques; 2) “ana” (AN as a lifestyle choice) versus AN (as a psychiatric condition); 3) social support; and 4) the need for AN. The results of this study suggest that participation in websites serves many purposes, as they mainly offer help in coping with problems related to severe weight loss, and they can be a space where patients deal with difficult emotions. Moreover, another study provided findings that suggest that pro-ED sites encourage restrictive and bulimic behaviors, which can contribute to the increase and worsening of the disorder.29 By collecting information from users of these sites through email exchanges, those users reported receiving more support for other stressors in their lives than regarding their concerns associated with food. They also reported receiving less support in their offline relationships (ie, in face-to-face interactions with people who live in their social environment) than from people they know online, both in terms of their general concerns and their eating-related difficulties.29

One of the articles suggested that all participants from the investigated pro-ana online communities reported high levels of eating concerns and ED symptoms.41 Participation in an online community served two purposes: to pursue weight loss and thinness; and to provide a sense of identity. The feeling of acceptance and relief found within the online community highlights the emotional benefits of an online support group. In contrast, the results indicated that there were practically no healthy messages being exchanged within the community; participants spontaneously referred only to advice regarding weight loss and restriction or purging behaviors. In summary, the study shows the harmful nature of pro-ana online communities, despite their contributions in terms of social support.

The findings of another article were in agreement with those of studies already described in this review; the authors showed that members of the sites feel that they receive less support in their significant relationships than among their colleagues and peers, and they seek to participate in online forums as a means to receive social support.27 Users also reported experiencing an improved psychological state after visiting these websites. However, despite the social support provided by the pro-ED websites, these sites are better understood as places that offer temporary relief from the hostility provided from people in the real environment (ie, offline).22 One cannot say that these sites offer therapeutic value beyond the online context.

Spiritual support

Only one study addressed the topic of spiritual support in the context of ED.30 The authors aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a spiritual intervention group in patients with ED, compared with two other groups: one with cognitive support, and one with emotional support (control group). The results showed that patients in the spiritual support group obtained significantly lower scores of psychological disorders and symptoms of ED at the end of treatment compared to patients from the other groups. These patients also obtained higher scores on spiritual well-being. In weekly evaluations that were performed by applying scales, patients from the spiritual support group showed more significant and faster improvement during the first 4 weeks of treatment than did patients from the other groups. This study provides evidence that investing in the spiritual growth and well-being of patients with ED during treatment may assist in reducing depression, anxiety, stress in relationships, and it can also mitigate conflicts between social roles and the symptoms of ED.

Conclusion

This integrative review provided evidence that there is still no fully consolidated literature review regarding social support and social networks in patients with ED, given the small number of studies dedicated to the subject. It was noted that the family network was the source of social support that was most frequently addressed by the studies included in this review (n=12). Such studies provided fairly convergent findings, especially with regard to the characteristics associated with family functioning among individuals with ED. These characteristics include, in general, dysfunctional relationship patterns, parental overload, conflicts related to the role of caregiver, difficulties in dealing with the stigma in one’s own family regarding the affected member, reunion or family breakdown, social isolation, financial difficulties, among others.20,26,28,32,34–37,39

By integrating and analyzing published studies, this review found that there was a predominance of studies published in international journals, coming mainly from the United States (n=11). This finding highlights the need for greater investment in worldwide publications on the various dimensions of social support and social networks in patients with ED. In particular, studies with more sophisticated levels of evidence, such as experimental and quasi-experimental studies, as well as randomized controlled trials should be conducted.

Critical evaluation of the included articles showed that there are gaps and inconsistencies in terms of how the ED can affect and be affected by social networks and support. The results differ with respect to the degree of satisfaction that affected women have concerning family support.3,6 However, the literature shows that there are similarities in the evidence, especially pertaining to the suffering that these women have experienced within their social networks, since they have difficulty in establishing deep bonds.20,32,35 These experiences seem to result in a distancing of the social network’s members and, consequently, in social isolation. The absence of regular social interactions with members of one’s social network seems to decrease the network’s potential for providing support in coping with the ED, thus contributing to its worsening.25,31,40

Considering that ED are health problems that directly affect the care provided by all health professionals, we highlight the need for further investigations that propose to discuss social support and social networks in the context of ED. The evidence presented in this study shows limitations regarding the need to include other social networks in health care, such as friends, colleagues, neighbors, people from religious groups, among others, who could help the individual coping with the disorder. Taking this into account, the prospective of future studies should address social networks beyond family bonds, since they include people who play important roles in providing social support to patients with ED.

In this overview, it is believed that increasing the number of qualified publications in this area could provide more evidence for clinical practice. This could lead to a more comprehensive understanding on the part of the professionals involved in care with respect to the levels of prevention of ED and health promotion. Such an understanding could provide subsidies for improvements in treatment, so that treatments do not remain focused only on eating-related symptoms; the disorder’s relational dimension should also be considered in health assistance.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for funding this research, process number 2014/03918-1.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bullock K. Family Social Support. In: Bomar PJ, editor. Promoting Health in Families: Applying Family Research and Theory to Nursing Practice. 3rd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2004. pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavaliere IAL, Costa SG. Social isolation, sociability and social care networks. Physis. 2011;21(2):491–516. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quiles Marcos Y, Terol Cantero MC. Assessment of social support dimensions in patients with eating disorders. Span J Psychol. 2009;12(1):226–235. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600001633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sluzki CE. The Social Network: Frontier of Systemic Practices. Barcelona, Spain: 1996. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright LM, Leahey M. Nurses and Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Co; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limbert C. Perceptions of social support and eating disorder characteristics. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(2):170–178. doi: 10.1080/07399330902893846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassin SE, von Ranson KM. Personality and eating disorders: a decade in review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(7):895–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpowicz E, Skärsäter I, Nevonen L. Self-esteem in patients treated for anorexia nervosa. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2009;18(5):318–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rørtveit K, Aström S, Severinsson E. The feeling of being trapped in and ashamed of one’s own body: A qualitative study of women who suffer from eating difficulties. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2009;18(2):91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea ME, Pritchard ME. Is self-esteem the primary predictor of disordered eating? Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(8):1527–1537. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akobeng AK. Principles of evidence based medicine. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):837–840. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broome ME. Integrative literature reviews for the development of concepts. In: Rodgers BL, Knafl KA, editors. Concept Development in Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2000. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pai M, McCulloch M, Gorman JD, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: an illustrated, step-by-step guide. Natl Med J India. 2004;17(2):86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganong LH. Integrative reviews of nursing research. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machado V, Leonidas C, Santos MA, Santos MA, Souza J. Psychiatric readmission: an integrative review of the literature. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(4):447–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramacciati N. Health Technology Assessment in nursing: a literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(1):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Favretto DO, Silveira RC, Canini SR, Garbin LM, Martins FT, Dalri MC. Endotracheal suction in intubated critically ill adult patients undergoing mechanical ventilation: a systematic review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20(5):997–1007. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692012000500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polit DF, Beck CT, Hungler BP. Essentials of Nursing Research: Methods, Appraisal, and Utilization. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dallos R, Denford S. A qualitative exploration of relationship and attachment themes in families with an eating disorder. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13(2):305–322. doi: 10.1177/1359104507088349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borzekowski DL, Schenk S, Wilson JL, Peebles R. e-Ana and e-Mia: a content analysis of pro-eating disorder Web sites. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1526–1534. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brotsky SR, Giles D. Inside the “pro-ana” community: a covert online participant observation. Eat Disord. 2007;15(2):93–109. doi: 10.1080/10640260701190600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulveen R, Hepworth J. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of participation in a pro-anorexia internet site and its relationship with disordered eating. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(2):283–296. doi: 10.1177/1359105306061187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutchinson DM, Rapee RM. Do friends share similar body image and eating problems? The role of social networks and peer influences in early adolescence. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1557–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooley E, Toray T, Wang MC, Valdez NN. Maternal effects on daughters’ eating pathology and body image. Eat Behav. 2008;9(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothschild-Yakar L, Levy-Shiff R, Fridman-Balaban R, Gur E, Stein D. Mentalization and relationships with parents as predictors of eating disordered behavior. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(7):501–507. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e526c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Csipke E, Horne O. Pro-eating disorder websites: users’ opinions. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2007;15(3):196–206. doi: 10.1002/erv.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzsimmons EE, Bardone-Cone AM. Coping and social support as potential moderators of the relation between anxiety and eating disorder symptomatology. Eat Behav. 2011;12(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ransom DC, La Guardia JG, Woody EZ, Boyd JL. Interpersonal interactions on online forums addressing eating concerns. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(2):161–170. doi: 10.1002/eat.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards PS, Berrett ME, Hardman RK, Eggett DL. Comparative efficacy of spirituality, cognitive, and emotional support groups for treating eating disorder inpatients. Eat Disord. 2006;14(5):401–415. doi: 10.1080/10640260600952548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shomaker LB, Furman W. Interpersonal influences on late adolescent girls’ and boys’ disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2009;10(2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunha AI, Relvas AP, Soares I. Anorexia nervosa and family relationships: perceived family functioning, coping strategies, beliefs, and attachment to parents and peers. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2009;9(2):229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winn S, Perkins S, Walwyn R, et al. Predictors of mental health problems and negative caregiving experiences in carers of adolescents with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(2):171–178. doi: 10.1002/eat.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillett KS, Harper JM, Larson JH, Berrett ME, Hardman RK. Implicit family process rules in eating-disordered and non-eating-disordered families. J Marital Fam Ther. 2009;35(2):159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillege S, Beale B, McMaster R. Impact of eating disorders on family life: individual parents’ stories. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(8):1016–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linville D, Brown T, Sturm K, McDougal T. Eating disorders and social support: perspectives of recovered individuals. Eat Disord. 2012;20(3):216–231. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.668480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campos LKS, Sampaio ABRF, Garica C, Jr, Magdaleno R, Jr, Battistoni MMM, Turato ER. Psychological characteristics of mothers of patients with anorexia nervosa: implications for treatment and prognosis. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2012;34(1):13–18. doi: 10.1590/s2237-60892012000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimitropoulos G, Carter J, Schachter R, Woodside DB. Predictors of family functioning in carers of individuals with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(8):739–747. doi: 10.1002/eat.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimitropoulos G, Freeman VE, Bellai K, Olmsted M. Inpatients with severe anorexia nervosa and their siblings: non-shared experiences and family functioning. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2013;21(4):284–293. doi: 10.1002/erv.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweetingham R, Waller G. Childhood experiences of being bullied and teased in the eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16(5):401–407. doi: 10.1002/erv.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodgers RF, Skowron S, Chabrol H. Disordered eating and group membership among members of a pro-anorexic online community. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20(1):9–12. doi: 10.1002/erv.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):221–296. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lima NN, do Nascimento VB, de Carvalho SM, et al. Childhood depression: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1417–1425. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S42402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Setor Bancário Norte [homepage on the Internet] Periodicos Acesso Livre Capes. Brasilia, Brazil: Higher Education Co-ordination Agency of Brazil’s Ministry of Education; 2000. [Accessed November 12, 2013]. Available from: http://www.periodicos.capes.gov.br. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]