Abstract

Objective

This study examined the extent to which protective behavioral strategies (PBS) mediated the influence of drinking motives on alcohol consumption, and if these hypothesized relationships were corroborated across subsamples of gender and race.

Method

Online surveys were completed by 1592 heavy drinking college undergraduates from two universities (49.9% male and 50.1% female; 76.9% Caucasian and 23.1% Asian). Independent samples t-tests compared males and females as well as Caucasians and Asians on measures of drinking motives, PBS use, and alcohol consumption, and structural equation models examined the mediating role of PBS.

Results

Consistent with predictions, t-tests revealed that males reported greater levels of consumption than females, but females reported greater use of PBS than males. Caucasians reported greater consumption levels, endorsed higher enhancement motives, and higher PBS related to serious harm reduction, but Asians endorsed higher coping and conformity motives, and PBS focused on stopping/limiting drinking. In multiple-sample SEM analyses, PBS were shown to largely mediate the relationship between motives and consumption in all demographic subsamples.

Conclusions

Findings indicate that PBS use leads to reductions in drinking despite pre-established drinking motives, hence pointing to the potential value of standalone PBS skills training interventions in lowering alcohol use among diverse groups of heavy drinking college students.

Keywords: Alcohol, Protective behavioral strategies, Drinking motives, College students, Gender, Race

1. Introduction

Heavy alcohol use on college campuses is a leading health and safety concern for campus administrators and public health officials. An estimated two in three college students report consuming alcohol in the past month (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010) and 44% of students report engaging in high risk or heavy episodic drinking (defined as 5+ drinks in a row for men and 4+ drinks in a row for women) at least once in the previous two weeks (Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Excessive drinking contributes to a range of serious negative consequences, including academic and psychological impairment, risky sexual behavior, car accidents, violence, and even death (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005; Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Furthermore, proximate peers and surrounding communities often suffer secondary consequences through vandalism, disruptive noise, and verbal, physical or sexual assault (Hingson et al., 2005, 2009; Wechsler et al., 2002; Yu, 2001). The current study sought to inform existing literature on the etiology of hazardous drinking among college students by examining how motivations for alcohol use may differ by gender and race and, further, how strategies used to protect oneself from drinking-related risk may mediate the relationship between drinking motives and consumption.

The use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS; Martens et al., 2005) during the active consumption of alcohol — examples include alternating alcohol and non-alcoholic drinks, and setting consumption limits — have emerged as effective strategies for reducing heavy alcohol consumption and related risk in college populations. Multi-component harm reduction interventions that have incorporated a PBS-based skills training component have found teaching PBS to be a powerful mediator of intervention effectiveness (Larimer et al., 2007; Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007). Further, cross-sectional studies assessing students’ utilization of PBS have found that students who utilize PBS when drinking experience fewer consequences than peers not employing PBS (Benton et al., 2004; Haines, Barker, & Rice, 2006; Larimer et al., 2007; Martens et al., 2004; Park & Grant, 2005). PBS initiatives concede that drinking alcohol is a normative behavior among college students and focus on reducing harm among those students choosing to drink.

To gain a better understanding of how PBS may minimize drinking-related harm, the current study examined the extent to which PBS mediated the predictive effect of a potential risk factor on alcohol consumption. Because drinking motives are well-established predictors of heavy drinking and considered most proximal to one’s drinking decisions (Cox & Klinger, 1988; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Engels, & Gmel, 2007; Westmaas, Moeller, & Woicik, 2007), assessing the role of drinking motives as a risk factor on PBS is informative. Further, given that students with higher levels of motivations to drink tend to drink more frequently and excessively than peers with lower drinking motives, it is expected that these students will also be less inclined to naturally utilize protective strategies when consuming alcohol. This prediction is supported by Martens, Ferrier, & Cimini’s, 2007 study, which revealed negative bivariate correlations between drinking motives (social, coping, and enhancement) and PBS employment. Moreover, Martens and colleagues demonstrated that PBS partially mediated the relationship between social and enhancement drinking motives, but not coping motives, on the outcome of risky drinking in a sample of 254 volunteer and judicially sanctioned college students. These findings are especially enlightening to harm reduction efforts by revealing that strategic drinking behaviors (i.e., PBS) mediated the powerful relationship between drinking motives and consumption. The current study sought to extend Martens and colleagues’ novel and important findings by using a large sample of heavy drinking college students to assess mean differences in drinking motives, PBS, and drinking as a function of gender and race (Caucasian vs. Asian-American), and, further, by examining the extent to which PBS mediated the relationship between drinking motives and level of alcohol consumption in each of these subgroups.

It is well-established that gender and race differences are linked to drinking behaviors; however, it is not known how these demographic variables may differ on a broader set of variables including drinking motives, PBS, and alcohol consumption. A better understanding of the connection between demographic characteristics and drinking could have significant implications for harm reduction interventions. Overall, research exploring gender differences in college students’ drinking motives has been inconsistent. Although many studies demonstrate that college males are more likely to endorse enhancement, social, and conformity motives than female peers (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Ham, Zamboanga, Bacon, & Garcia, 2009; Wild, Hinson, Cunningham, & Bacchiochi, 2001), others have evidenced minimal or no gender differences (Gonzalez, Collins, & Bradizza, 2009; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001). Research assessing the use of PBS and drinking risk, on the other hand, have consistently shown that women tend to implement protective behaviors more often and more effectively than men (Benton et al., 2004; Delva et al., 2004; Haines et al., 2006; Walters, Roudsari, Vader, & Harris, 2007).

With regard to racial–ethnic status, Asian-American students are of particular interest due to escalating rates of alcohol abuse and binge drinking in this population (see Grant et al., 2004; Wechsler, Dowdall, Maenner, Gledhill-Hoyt, & Lee, 1998). Moreover, in a sample of 204 undergraduates (51.7% Caucasian, 40.8% Asian/Asian-American, 7.5% other), Neighbors, Larimer, Geisner, and Knee (2004) found that Asian-American students were more likely to endorse conformity motives but less likely to endorse enhancement motives for drinking as compared to non-Asian-American peers, thus supporting that underrepresented non-Caucasian students may seek to drink according to heavy drinking white student campus norms (Martens, Rocha, Martin, & Serrao, 2008). However, despite recent evidence highlighting the unique risk that Asian-American college students may face, few studies have examined this group’s alcohol use behaviors and no studies to date have examined PBS usage in an Asian cohort.

1.1. Study aims and hypotheses

The current study examined levels of drinking motives, PBS, and actual drinking as a function of gender and race. Furthermore, we developed a model proposing that drinking motives are predictive of alcohol consumption, and that the strength of this direct link is attenuated after accounting for the use of PBS. Consistent with established research, higher drinking motives are expected to be predictive of increased alcohol consumption. Further, the following hypotheses are proposed as they relate to the mediational model: higher drinking motives should predict decreased use of protective strategies and the utilization of protective strategies should then predict decreased alcohol use. In summary, PBS usage should mediate the direct relationship between drinking motives and consumption. Additional analyses examined if this mediational model was tenable across gender and race.

A central goal of the current study is to shed light on the potential efficacy of an isolated PBS-based intervention. A better understanding of how PBS may mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol risk, and within subgroups of students, is valuable to informing alcohol prevention initiatives targeting at-risk college students. PBS have shown potential as effective harm minimization strategies within multi-component collegiate alcohol interventions and are found to be routinely employed by college students (Haines et al., 2006), thus suggesting that these skills may be intuitive for students to learn. Further, naturally occurring PBS use has been found to be especially beneficial to heavier drinking subgroups of students (Benton et al., 2004) and therefore PBS-based interventions aimed at those students most in need of reducing drinking and consequences offer an important avenue for future harm reduction approaches.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Among participants completing the online screening survey (N=4984), we computed the percentage in each group that screened into the subsequent baseline survey. The screening criteria will be described in the design and procedure section. For males (n=1995), 39.8% (n=794) screened into the study; for females (n=2274), 35.1% (n = 798) screened into the study. Among Caucasians (n=2102), 58.2% (n=1224) screened into the study; for Asians (n=1145), only 32.1% (n=368) screened into the study.

Respondents who met the screening criteria, and therefore made up the baseline sample used in our analyses, were 1592 heavy-drinking Caucasian and Asian college students. Participants in this final sample reported a mean age of 19.94 (SD=1.33) — of which 64.0% were under the legal drinking age (21 years) — with a gender distribution of 49.9% male and 50.1% female, and a racial distribution of 76.9% Caucasian and 23.1% Asian. In this final sample, participants in the public university consisted of 57.4% male, and racially distributed with 66.7% Caucasian and 33.3% Asian; participants in the private university consisted of 38.9% male, and racially distributed with 91.7% Caucasian and 8.3% Asian.

2.2. Design and procedure

During the fall semester of 2008, a randomly selected group of 11,069 students across both campuses were invited to participate in a confidential study regarding alcohol use and perceptions of drinking in college. The universities included a large public institution with approximately 30,000 undergraduates and a mid-sized private institution with approximately 5500 undergraduates. The 4984 students who consented to participate in the study clicked on a designated link to access an online screening survey. Responses in the screening survey established eligibility for participation in the subsequent baseline survey. To screen into the subsequent baseline survey study, participants racially identified as either Caucasian or Asian and reported at least one episode of heavy episodic drinking in the past month (5 drinks in a row for males and 4 drinks in a row for females). All respondents signed a local IRB-approved consent form at the beginning of both the screening and baseline surveys and were paid a nominal stipend upon completion of each survey. Those 1592 (31.9%) students who met the screening criteria and completed the baseline survey with non-missing responses make up the current sample.

2.3. Measures

Measures appropriate to the current study include drinking motives, PBS, alcoholic consumption, drinking hours, and drinking days.

2.3.1. Drinking motives

Motivations for drinking alcohol were assessed using the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994), a rigorously tested and validated measurement of drinking motives (MacLean & Lecci, 2000; Stewart et al., 2001). Respondents were prompted with, “Thinking of the time you drank in the past 30 days, how often would you say that you drank for the following reasons?” and were instructed to rate each reason using a 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always) scale. Each question corresponded to one of the following four subscales: Social Motives (α=.89; e.g., “Because it helps you enjoy a party”), Coping (α=.89; e.g., “To forget your worries”), Enhancement (α=.88; “Because you like the feeling”), and Conformity (α=.90; e.g., “Because your friends pressure you to drink”).

2.3.2. Protective behavioral strategies

Participants completed Protective Behavioral Strategy Scale (PBSS; Martens et al., 2005) to assess cognitive–behavioral strategies used to reduce risky drinking. The PBSS is a psychometrically validated measurement of alcohol protective behavior (Benton et al., 2004; Martens et al., 2005; Martens, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007; Martens, Pederson, LaBrie, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007; Walters et al., 2007). The 15-item measure uses a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) in which participants indicate the degree to which they engage in certain behaviors when using alcohol or ‘partying’. The measure is divided into the three following subscales: Stopping/Limiting Drinking (α=.90; e.g., “Determine not to exceed a set number of drinks”), Manner of Drinking (α=.63; e.g., “Drink slowly, rather than gulp or chug”), and Serious Negative Consequences (α=.71; e.g., “Know where your drink has been at all times”).

2.3.3. Drinks

The alcoholic drinks factor was measured with three items representing drinks per week, hours per week drinking, and days per month drinking. Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999) assessed both drinks per week and hours per week drinking. Participants were instructed to consider a typical week in the past month before answering, “How many drinks did you typically consume on a Monday? Tuesday?” and so forth. Students’ open-ended responses across these seven days were summed to form a ‘drinks per week’ variable that was used in this analysis. For each day of the week that participants reported drinking alcohol, they were asked to provide an open ended estimate of the number of hours they consumed drinks on each of these days. For example, “You said you typically have drink(s) on MONDAY. Over how many hours?” The responses were summed to yield ‘hours per week’ drinking. To assess ‘days per month’ drinking, respondents answered the question, “How many days of the week did you drink alcohol during the past month?” using a scale ranging from 0 to 7 and including, for example, 0 (I do not drink at all), 2 (twice a week), 4 (four times a week), and 7 (every day).

2.4. Analytic plan

Correlations across the subscales of DMQ, PBS, and drinks were examined separately for the subgroups within gender (males and females) and race (Caucasians and Asians). Independent samples t-tests on these variables determined significant group-based mean differences as a function of gender and then of race.

A hypothesized mediational model evaluated the effect of drinking motives on level of alcohol consumption, and whether this pathway was statistically mediated through the usage of PBS. The mediational model was specified via the three-equation procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986): (1) Predictor must directly influence the outcome; (2) Predictor must influence the mediator; and (3) Mediator must influence the outcome after controlling for the predictor. After accounting for the mediator, the level of reduction in the magnitude of the predictor on the outcome reflects the strength of the mediational effect. The proposed theoretical framework was estimated with latent structural equation modeling, and specified with EQS 6.1 (Bentler, 2005). The drinking measures, because they were based on different response scales, were standardized prior to entry into the model. Consistent with a latent approach and to provide a parsimonious model, the subscales within each DMQ, PBS, and drinking were treated as parcels and allowed to load on their respective factors. For the purpose of estimation, the first indicator of each latent factor was fixed to 1.

Finally, if the underlying data supported the overall hypothesized model, multi-sample analyses followed, according to the sequence recommended by Byrne (2006). Specifically, tests of measurement invariance assessed equivalency of factor loadings between males and females, and then between Caucasians and Asians. Subsequently building on these analyses were tests of structural invariance, the objective of which was to assess the equivalency in factor-to-factor pathways between the gender groups and then the racial groups.

Several fit indices were interpreted to assess the goodness-of-fit of our structural equation models. We examined the scaled χ2 (Satorra & Bentler, 1994), which corrects for multivariate non-normality of variables. A non-significant χ2 value is desired, and indicates that the hypothesized model overlaps with the underlying data, but this test is considered sensitive to model rejection when the sample size, like the one of this study, is large (Bollen, 1989). Thus, the CFI and NFI were evaluated, with models yielding higher values, preferably over .90, indicating a better approximation of the underlying data (Ullman & Bentler, 2003). Also reported as a judgment of model fit was the RMSEA, a residual-based index, with lower values, preferably below .10, indicating a better fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Given the sample size and number of statistical comparisons, all tests were assessed using a conservative p<.001.

3. Results

3.1. Correlation matrix

Correlations of the measured variables, used to form the factors in the subsequent SEM analyses, are organized by gender (Table 1) and race (Table 2). Overall, in identifying consistent correlational patterns across these groups, the drinking motives subscales tended to be negatively correlated with the subscales of PBS, but positively correlated with the drinking variables. The PBS subscales tended to be negatively correlated with the drinking variables.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix for males (n=794) and females (n=798).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DMQ — social | – | .37 | .62 | .27 | −.18 | −.27 | −.08 | .24 | .15 | .18 | |

| 2. DMQ — coping | .35 | – | .30 | .49 | −.08 | −.17 | −.21 | .10 | .09 | .06 | |

| 3. DMQ — enhancement | .54 | .31 | – | .21 | −.21 | −.31 | −.07 | .31 | .21 | .25 | |

| 4. DMQ — conformity | .23 | .50 | .19 | – | −.09 | −.11 | −.17 | .00 | .00 | −.01 | |

| 5. PBS — stopping/limiting drinking | − | .10 | .00 | −.13 | .05 | – | .44 | .28 | −.24 | −.13 | −.18 |

| 6. PBS — manner of drinking | − | .27 | −.14 | −.30 | −.12 | .35 | – | .30 | −.37 | −.18 | −.20 |

| 7. PBS — serious harm reduction | − | .13 | −.21 | −.17 | −.22 | .26 | .22 | – | −.10 | −.09 | −.07 |

| 8. Drinks — drinks per week | .21 | .10 | .30 | .05 | −.15 | −.30 | −.17 | – | .75 | .69 | |

| 9. Drinks — hours per week | .13 | .08 | .22 | −.01 | −.09 | −.17 | −.15 | .79 | – | .64 | |

| 10. Drinks — days per month | .16 | .14 | .20 | .02 | −.12 | −.14 | −.18 | .65 | .63 | – |

Note. Values below diagonal are from males; Values above diagonal are from females.

For both males and females, correlations of at least /.12/ are statistically significant, p<.001.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for Caucasians (n=1224) and Asians (n=368).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DMQ — social | – | .33 | .55 | .23 | −.19 | −.24 | −.11 | .17 | .16 | .20 | |

| 2. DMQ — coping | .38 | – | .36 | .46 | .01 | −.09 | −.23 | .00 | .02 | .05 | |

| 3. DMQ — enhancement | .60 | .32 | – | .23 | −.21 | −.30 | −.18 | .29 | .23 | .18 | |

| 4. DMQ — conformity | .25 | .49 | .21 | – | −.03 | −.12 | −.23 | −.04 | −.09 | −.01 | |

| 5. PBS — stopping/limiting drinking | − | .15 | −.10 | −.16 | −.05 | – | .41 | .26 | −.17 | −.07 | −.14 |

| 6. PBS — manner of drinking | − | .29 | −.18 | −.32 | −.12 | .43 | – | .31 | −.30 | −.16 | −.20 |

| 7. PBS — serious harm reduction | − | .11 | −.16 | −.13 | −.19 | .35 | .29 | – | −.21 | −.09 | −.22 |

| 8. Drinks — drinks per week | .25 | .17 | .28 | .10 | −.22 | −.37 | −.26 | – | .74 | .66 | |

| 9. Drinks — hours per week | .15 | .15 | .20 | .06 | −.12 | −.21 | −.20 | .75 | – | .66 | |

| 10. Drinks — days per month | .19 | .18 | .22 | .05 | −.17 | −.20 | −.20 | .66 | .63 | – |

Note. Values below diagonal are from Caucasians; Values above diagonal are from Asians.

For Caucasians, correlations of at least /.10/ are statistically significant, p<.001; For Asians, correlations of at least /.17/ are statistically significant, p<.001.

3.2. Mean differences

Mean differences as a function of gender are presented in Table 3. Males endorsed significantly higher values on the drinking subscales of drinks per week, hours per week drinking, and days per month drinking, p<.001; but females endorsed significantly higher values on the PBS subscales of stopping/limiting drinking, manner of drinking, and serious harm reduction, p<.001.

Table 3.

Mean differences between males (n=794) and females (n=798) on variables.

| Males

|

Females

|

t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| DMQ — social | 3.54 | (0.94) | 3.43 | (0.97) | 2.44 |

| DMQ — coping | 1.80 | (0.91) | 1.79 | (0.86) | 0.30 |

| DMQ — enhancement | 3.11 | (1.00) | 3.01 | (0.99) | 2.12 |

| DMQ — conformity | 1.50 | (0.77) | 1.39 | (0.64) | 3.07 |

| PBS — stopping/limiting drinking | 2.56 | (0.72) | 2.84 | (0.76) | −7.57*** |

| PBS — manner of drinking | 2.76 | (0.65) | 2.99 | (0.66) | −6.89*** |

| PBS — serious harm reduction | 4.00 | (0.77) | 4.51 | (0.66) | −14.20*** |

| Drinks — drinks per week | 14.24 | (11.44) | 8.79 | (6.57) | 11.66*** |

| Drinks — hours per week | 8.73 | (6.05) | 7.55 | (5.21) | 4.19*** |

| Drinks — days per month | 1.91 | (1.27) | 1.52 | (1.09) | 6.53*** |

Note. DMQ subscales range from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). PBS subscales range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Drinks per week and hours per week are open-ended and days per month is on a scale from 0 (I do not drink at all) to 7 (every day).

p<.001.

Mean differences as a function of race are displayed in Table 4. Caucasians reported significantly higher levels of enhancement motives, the PBS of serious harm reduction, and the drinking variables of drinks per week, hours per week drinking, and days per month drinking, p<.001. Asians, however, reported higher scores on the motives of coping and conformity, and the PBS of stopping/limiting drinking than Caucasians, p<.001. When gender×race ANOVAs were performed on the measures, interaction effects were not evidenced.

Table 4.

Mean differences between Caucasians (n=1224) and Asians (n=368) on variables.

| Caucasians

|

Asians

|

t-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| DMQ — social | 3.45 | (0.95) | 3.59 | (0.97) | −2.33 |

| DMQ — coping | 1.71 | (0.80) | 2.09 | (1.07) | −7.31*** |

| DMQ — enhancement | 3.11 | (0.98) | 2.87 | (1.01) | 4.06*** |

| DMQ — conformity | 1.40 | (0.68) | 1.60 | (0.79) | −4.77*** |

| PBS — stopping/limiting drinking | 2.65 | (0.73) | 2.84 | (0.83) | −4.31*** |

| PBS — manner of drinking | 2.89 | (0.65) | 2.81 | (0.70) | 1.99 |

| PBS — serious harm reduction | 4.31 | (0.72) | 4.09 | (0.85) | 4.97*** |

| Drinks — drinks per week | 12.20 | (9.93) | 9.19 | (8.58) | 5.26*** |

| Drinks — hours per week | 8.61 | (5.81) | 6.57 | (4.89) | 6.13*** |

| Drinks — days per month | 1.82 | (1.22) | 1.38 | (1.08) | 6.14*** |

Note. DMQ subscales range from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). PBS subscales range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Drinks per week and hours per week are open-ended and days per month is on a scale from 0 (I do not drink at all) to 7 (every day).

p<.001.

3.3. Mediational model

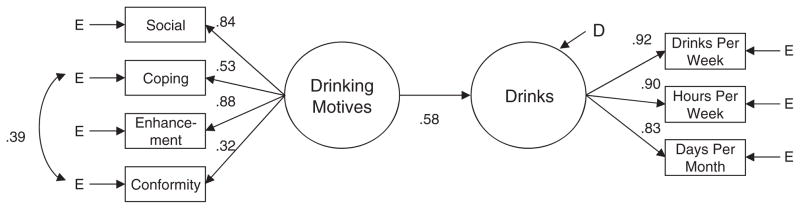

The structural equation model of drinking motives predicting drinks was found to be of satisfactory fit, χ2 (13)=547.86, p<.001, CFI=.95, NFI=.95, RMSEA=.10. Lagrange Multiplier (LM) modification tests suggested that the model could be significantly improved by correlating the error terms of coping and conformity motives. Generally, post-hoc modifications should be avoided, but correlating the error terms between these two motives may be theoretically justified, on the grounds that coping and conformity represent negative drinking motivations (Cooper, 1994). This was the only post-hoc modification made to the hypothesized model. As presented in Fig. 1, the revised model involving the direct effect of drinking motives on drinking produced a much better fit. Specifically, higher drinking motives were shown to influence higher levels of drinking (β=.58, p<.001).

Fig. 1.

Direct effect of drinking motives on drinking. Note. χ2 (12)=153.56, p<.001, CFI=.99, NFI=.98, RMSEA=.05. N=1592. D=disturbance. Standardized values are presented. All factor loadings and paths are significant at p<.001.

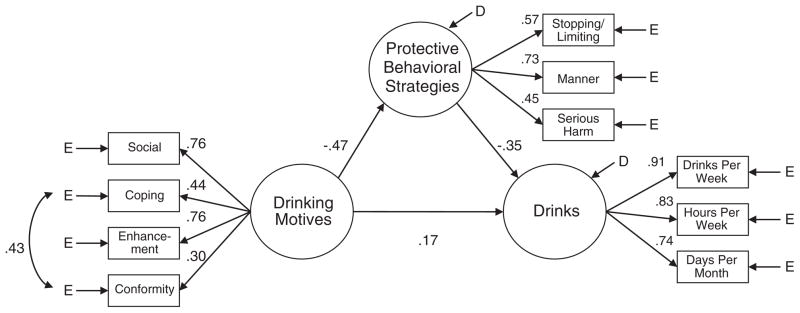

The overall mediation model, depicted in Fig. 2, produced an acceptable fit. Specifically, higher drinking motives predicted decreased use of protective strategies (β=−.47, p<.001); and usage of protective strategies, in turn, predicted fewer alcoholic drinks (β=−.35, p<.001). After statistically accounting for the mediating effect of PBS, the magnitude of the direct path from drinking motives to alcoholic drinks was attenuated to .17 (p<.001), suggesting that PBS largely explicated and therefore reduced this potentially hazardous link. A test of indirect effect further corroborated that PBS significantly mediated the pathway from drinking motives to drinks, p<.001.

Fig. 2.

Protective behavioral strategies mediating the effect of drinking motives on drinking. Note. χ2 (31)=215.56, p<.001, CFI=.95, NFI=.94, RMSEA=.06. N=1592. D=disturbance. Standardized values are presented. All factor loadings and paths are significant at p<.001.

3.4. Tests of multi-sample invariance

The fit indices of the various multi-sample invariance analyses are presented in Table 5. The overall mediational models, specified in the same manner as detailed in the overall sample, were first estimated separately for males and females. Afterward, we analyzed the configural baseline model for gender, in which the male and female models were simultaneously estimated. Next, all freely estimated factor loadings for the male and female models were constrained to be equal. Unequal factor loadings as a function of gender were evidenced on two drink items: hours per week (p<.001) and days per month (p<.001). Accordingly, equality constraints for these two items were released, and additional imposition of equality constraints for all the factor-to-factor paths revealed that the effect of protective strategies on drinking appeared significantly stronger in females (β=−.35, p<.001) than males (β=−.20, p<.001).

Table 5.

SEM multi-sample analyses for gender and race.

| X2 | df | p-value | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 133.32 | 31 | <.001 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.07 |

| Females | 120.82 | 31 | <.001 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.06 |

| Baseline model | 253.85 | 62 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 |

| Factor loadings constrained | 309.81 | 69 | <.001 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.07 |

| Factor loadings and factor-to-factor paths constrained (2 unequal factor loadings released) | 273.72 | 70 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasians | 165.55 | 31 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.06 |

| Asians | 79.74 | 31 | <.001 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.07 |

| Baseline model | 244.84 | 62 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 |

| Factor loadings constrained | 248.35 | 69 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 |

| Factor loadings and factor-to-factor paths constrained | 255.54 | 72 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 |

Also presented in Table 5, the mediational models were shown to yield satisfactory fit for Caucasians and Asians separately. The configural baseline model for race, involving the simultaneous estimation of Caucasian and Asian models, was then examined. Next, all freely estimated factor loadings between the Caucasian and Asian models were constrained to be equal. None of the factor loadings were found to be significantly different between these two racial groups. Subsequently, additional equality constraints imposed on all the factor-to-factor paths showed that none of these structural paths emerged as significantly different between the two racial groups, suggesting that the mediational models fitted equally well across Caucasians and Asians.

4. Discussion

Previous research indicates that there is a highly predictive link between drinking motives and alcohol use. In this large sample of heavy drinking Asian and Caucasian college students, the mediational model showed that the link between motives and drinking was weakened after controlling for PBS. Consistent with past studies, the results indicated that greater motivation to drink was associated with lower utilization of protective strategies, but also that PBS use was associated with consumption of fewer drinks. The current findings augment the growing body of evidence that PBS is associated with less risky drinking, and point to the potentially immense value of a standalone PBS skills training intervention in lowering alcohol use among heavy drinking college students.

The large sample size in this study enabled an examination of gender and race in greater detail. In concurrence with previous findings (Benton et al., 2004; Delva et al., 2004; Haines et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2007), tests of mean differences reveal that females were significantly more likely to use PBS than males, whereas males drank more per sitting, more often, and over longer periods of time, than females. However, no such gender differences in drinking motives emerged, so that males and females were equally motivated to drink.

Among this heavy drinking sample, multi-sample tests of invariance revealed that the use of PBS was more effective for women than men in reducing alcohol consumption. This particular finding is notable given previous research showing that heavy episodic drinking is associated with increased likelihood of being a victim of sexual aggression in women (Howard, Griffin, & Boekeloo, 2008; Parks & Fals-Stewart, 2004). Equipping women with PBS then, may be especially warranted to minimize alcohol-related harm including deleterious sexual consequences. PBS-based interventions targeted at women’s groups that are more likely to engage in risky drinking, such as sororities or athletic teams, would be a prudent use of these research findings. This does not imply, however, that such interventions should be restricted to women only. Indeed, men too may greatly benefit from PBS-based interventions, given current findings that PBS use significantly predicted reduced alcohol consumption among men, albeit to a lesser degree than it did among women. As men may be at an increased overall risk of experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences because of their higher drinking levels, equipping them with PBS may be of immense value to them.

In addition, the results of this study indicate that although Asian students who drink do so at lower levels than their Caucasian peers, they may still be consuming alcohol in quantities that expose them to a considerable risk of negative consequences. Hence we would speculate that examining PBS use in Asian students is warranted. It must be noted however, that the Asian participants, because they were selected into the study as heavy drinkers, may be a unique cohort in their lower susceptibility to the flushing response — a reaction due to a genetic predisposition among many Asian groups that is typified by numerous undesirable physiological reactions to alcohol consumption (e.g., facial flushing, nausea, vomiting; see Wall & Ehlers, 1995). Hence, the current findings must be interpreted with caution. The Asians in this study, however, demonstrate risky alcohol consumption levels that may expose them to alcohol related harm. Concurrent with increasing evidence that risky drinking among Asian students is escalating (Grant et al., 2004, Wechsler et al., 1998), the current study points to the necessity for interventions that are effective in reducing drinking and associated consequences among heavy drinking Asian student populations.

Consistent with findings of previous studies, mean scores show that Caucasians were more likely to report higher drinking motives aimed at enhancing positive mood, whereas Asians were more likely to report higher coping and conformity motives (Neighbors et al., 2004; Martens et al., 2008; Theakston, Stewart, Dawson, Knowlden-Loewen, & Lehman, 2004). Perhaps Asian students, as members of a minority group, may be motivated to conform to the normative drinking culture of the predominantly Caucasian student body, which aligns with findings of past landmark studies showing that the minority is significantly influenced to conform to the majority group’s norms (Asch, 1951). In addition, PBS use varied by ethnicity such that Asians were more likely to use strategies to cease or limit drinking, whereas Caucasians endorsed use of strategies that minimize serious harm. This may be culturally grounded, whereby students’ behaviors are influenced by messages conveyed to them from family members and popular culture. For example, Asian cultural norms have been shown to emphasize drinking in moderation (Lu, Engs, & Hanson, 1997; Zane & Huh-Kim, 1998) as well as avoiding “loss of face” or negative evaluations from others (Zane & Yeh, 2002). This, combined with Asians’ predisposition to drinking induced flushing response, may make strategies associated with limiting consumption more appealing to these individuals (see Wall & Ehlers, 1995).

In the current study, multi-sample tests of invariance show that the mediational model was found to fit equally well between Caucasians and Asians. Therefore, the use of protective strategies was found to be equally effective for Caucasians and Asians in mediating the influence of motivation to drink on the level of alcohol consumed. One implication of this finding pertains to diversity on college campuses. Salient in evaluating the clinical utility of any intervention is a consideration of its applicability to diverse populations, which is a notable concern given rapidly increasing racial and ethnic diversity on college campuses. In light of this, PBS show tremendous potential as a culturally sensitive intervention approach that may be valuable regardless of racial or ethnic status, and hence applicable to a diverse student body. Perhaps of significance here is the flexibility afforded by a PBS intervention, in equipping students with a variety of techniques from which they may choose to utilize those that are most personally applicable given their culturally-grounded preferences. Further research with racial and ethnic groups other than Caucasians and Asians, of course, is necessary to document if similar patterns can be seen in the mediational effects of PBS in the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use.

This study is limited in several ways. First, the current analyses were restricted to heavy drinking college students, and implications of findings must be considered in this light. Second, the study design did not permit fine-grained examination of ethnic subgroups; we were limited to examining Asians and Caucasians as homogeneous racial groups. Future research would benefit from examining PBS use across various ethnic subgroups, to explore further the utility of PBS-based alcohol-related harm reduction interventions in diverse populations. Asian Americans, for example, may identify with one of 15 distinct ethnic groups, with unique drinking behaviors and beliefs about alcohol use. Korean and Filipino college students, for example, have been found to endorse more positive alcohol-related expectancies and drink at higher rates than Chinese or Vietnamese subgroups (Chang, Shrake, & Rhee, 2008; Luczak, Wall, Shea, Byun, & Carr, 2001; Lum, Corliss, Mays, Cochran, & Lui, 2009). Another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. A prospective study, collecting data prior to, and at various time-points following, a PBS-based intervention targeting an ethnically diverse sample of high-risk drinkers, would be a valuable direction for future research endeavors, to enable an examination of long-term effects of PBS training in reducing levels of alcohol consumption. A further limitation of the current study is the PBS scales were not time- or event-specific, such that participants simply indicated the extent in which they generally engaged in each strategy. Future research might seek to provide a time constraint (e.g., past week) when asking participants to respond to each PBS question, or might even consider rephrasing the instructions to assess event-specific PBS use (e.g., during pre-partying). Though the current study was designed to investigate the mediational role of PBS, alcohol research additionally would prosper from examining whether the effect of drinking motives on drinking is moderated by different levels of PBS. Finally, although the current analyses aggregated the drinking motives subscales into a latent factor for several empirically valid reasons, including for the sake of parsimony, prior research has demonstrated that types of drinking motives (coping, conformity, enhancement, and social) differentially impact drinking behavior. As such, when statistically appropriate, future studies may benefit from assessing the distinct contributions of each subscale as they predict PBS use.

Reducing students’ pre-established drinking motives for alcohol in order to lower alcohol consumption is a daunting endeavor that involves the immense task of changing prevalent drinking culture in American college campuses. Instead, attenuating the impact of these existing motives by training students in PBS use offers a more practical and expeditious route in alcohol-related harm reduction efforts. The current study provides strong support that PBS training has practical potential to assist students in reducing their alcohol-related risks.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported by Grant R01 AA 012547-06A2 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and Grant Q184H070017 from the U.S. Department of Education. Neither the NIAAA nor DOE had a role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Joseph LaBrie, Shannon Kenney, Tehniat Mirza, and Andrew Lac have each contributed significantly to this manuscript. Specifically, Dr. LaBrie generated the idea for the study, performed the major analyses, contributed to writing all sections of the manuscript, and oversaw its production. Shannon Kenney and Tehniat Mirza performed the literature review, drafted the Introduction, Method, and Discussion sections, and contributed to the Results section. Andrew Lac wrote the Results section, contributed to the Method and Discussion, and created the tables and figures.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Joseph W. LaBrie, Email: jlabrie@lmu.edu.

Andrew Lac, Email: Andrew.Lac@cgu.edu.

Shannon R. Kenney, Email: shannon.kenney@lmu.edu.

Tehniat Mirza, Email: tmirza@lmu.edu.

References

- Asch SE. Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In: Guetzkow H, editor. Groups, leadership, and men. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Press; 1951. pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Benton SL, Schmidt JL, Newton FB, Shin K, Benton SA, Newton DW. College student protective strategies and drinking consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(1):115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.115. Retrieved from. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Shrake E, Rhee S. Patterns of alcohol use and attitudes toward drinking among Chinese and Korean American college students. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7(3):341–356. doi: 10.1080/15332640802313346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Smith MP, Howell RL, Harrison DF, Wilke D, Jackson DL. A study of the relationship between protective behaviors and drinking consequences among undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53(1):n19–26. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Collins RL, Bradizza CM. Solitary and social heavy drinking, suicidal ideation, and drinking motives in underage college drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(12):993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MP, Barker G, Rice RM. The personal protective behaviors of college student drinkers: Evidence of indigenous protective norms. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55(2):69–76. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.2.69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, Garcia TA. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009 doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. (Writer) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26(1):259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman E. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(1 suppl):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. Supplement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Griffin MA, Boekeloo BO. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of alcohol-related sexual assault among university students. Adolescence. 2008;43(172):733–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2009: Volume I, Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 10-7584) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. Retrieved from. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/vol1_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Drinking motives as mediators of the link between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):76–85. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Mallett KA, Feeney M, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu ZP, Engs RC, Hanson DJ. The drinking behaviors of a sample of university students in Nanning, Guangxi Province, People’s Republic of China. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32:495–506. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Wall TL, Shea SH, Byun SM, Carr LG. Binge drinking in Chinese, Korean, and White college students: Genetic and ethnic group differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(4):306–309. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum C, Corliss HL, Mays VM, Cochran SD, Lui CK. Differences in the drinking behaviors of Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and Vietnamese college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2009;70:568–574. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.568. Retrieved from. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(1):83–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Do protective behavioral strategies mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college students? Retrieved from. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.106. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Korbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. Retrieved from. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pederson ER, LaBrie JW, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Rocha TL, Martin JL, Serrao HF. Drinking motives and college students: Further examination of a four-factor model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(2):289–295. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Geisner IM, Knee CR. Feeling controlled and drinking motives among college students: Contingent self-esteem as a mediator. Self and Identity. 2004;3(3):207–224. doi: 10.1080/13576500444000029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K, Fals-Stewart W. The temporal relationship between college women’s alcohol consumption and victimization experiences. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(4):625–629. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000122105.56109.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variable analysis: Applications for developmental research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domains and drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(2):271–286. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00044-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Theakston JA, Stewart SH, Dawson MY, Knowlden-Loewen SAB, Lehman DR. Big-5 personality domain predict drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2003. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Ehlers CL. Genetic influences affecting alcohol use among Asians. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1995;19(3):184–189. Retrieved from. http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Publications/AlcoholResearch/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Roudsari BS, Vader AM, Harris TR. Correlates of protective behavior utilization among heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2633–2644. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997. Journal of American College Health. 1998;47(2):57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. Retrieved from. http://www.acha.org/Publications/JACH.cfm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. Retrieved from. http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmaas J, Moeller S, Woicik PB. Validation of a measure of college students’ intoxicated behaviors: Associations with alcohol outcome expectancies, drinking motives, and personality. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55(4):227–237. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild TC, Hinson R, Cunningham J, Bacchiochi J. Perceived vulnerability to alcohol-related harm in young adults: Independent effects of risky alcohol use and drinking motives. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(1):117–125. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.9.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. Negative consequences of alcohol use among college students: Victims or victimizers? Journal of Drug Education. 2001;31(3):271–287. doi: 10.2190/HFAT-L1TN-G9G6-74KN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane NWS, Huh-Kim J. Addictive behaviors. In: Lee LC, Zane NWS, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 527–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Yeh M. The use of culturally-based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face. In: Kurasaki KS, Sue S, editors. Asian American mental health: Assessment, methods and theories. New York, NY: Kluwer; 2002. pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]