Abstract

This study examined the prospective relationship between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence in a community sample of 416 two-parent families in the Southeastern USA. Adolescents’ externalizing problems and their emotional insecurity with parents were examined as mediators. Parents’ psychological control was uniquely associated with adolescents’ friendship competence. When both mediators were included in the same model, adolescents’ perceptions of emotional insecurity in the parent–adolescent relationship fully mediated the association between parents’ psychological control and adolescents’ friendship competence. Parental hostility was associated with friendship competence indirectly through adolescents’ emotional insecurity. Results contribute to identifying the mechanisms by which parenting affects youths’ friendship competence, which is important in informing theory and practice regarding interpersonal relationships in adolescence.

Keywords: emotional insecurity, externalizing problems, friendship competence, parenting

Introduction

Friendship competence is a critically important developmental task for adolescents (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). Competencies needed to maintain friendships during adolescence differ somewhat from competencies needed to maintain relationships with childhood friends and may be more similar to those needed in adult relationships (Engels, Finkenauer, Meeus, & Dekovic, 2001). Friendship competence during adolescence includes establishing intimacy, giving and receiving support, and managing conflict (Burleson, 1995). Adolescents who have difficulty mastering these competencies are at risk for psychosocial problems during adolescence (Allen, Porter, & McFarland, 2006; Hussong, 2000) and for problems with accomplishing important developmental tasks during young adulthood (Roisman et al., 2004).

Adolescents’ relationships with parents are important predictors of friendship competence (Cui, Conger, Bryant, & Elder, 2002; Engels et al., 2001). Parenting behaviors employed during early adolescence may have a particularly important influence on youths’ ability to accomplish developmental tasks during early and middle adolescence (Galambos, Barker, & Almeida, 2003). Surprisingly, few researchers have directly examined whether parenting behaviors during the transition to early adolescence, as opposed to parenting during childhood, are important predictors of youths’ ability to form competent friendships by middle adolescence. Furthermore, with the exception of Cui et al. (2002), few studies have examined processes by which parenting affects adolescents’ friendships. Two important factors that might explain why parenting affects friendship competence are behavioral characteristics of youth (i.e., externalizing behaviors) and cognitions that adolescents have about relationships (i.e., emotional insecurity). To address these significant gaps in the literature, this study tests a prospective model that suggests negative parenting behaviors during early adolescence are associated with adolescents’ friendship competence during middle adolescence through their relations with youth externalizing problems and/or perceptions of emotional security with parents. Examining this model contributes to the literature in two important ways: (a) by examining the unique effects of two parenting behaviors in early adolescence on adolescents’ ability to develop competent friendships during middle adolescence; and (b) by examining two processes by which parenting may affect friendship competence. This is done using a prospective research design that includes multiple informant and method assessments, as well as five annual waves of data.

Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

The developmental contextual approach suggests that individuals’ experiences in family relationships influence their functioning in later relationships (Conger, Cui, Elder, & Bryant, 2000). Adolescents who experience hostile and/or psychologically controlling parenting may have difficulty developing competent relationships with peers. Parental hostility is the extent to which parents express harsh, angry, and critical behavior toward adolescents (Melby & Conger, 2001). Psychological control is characterized by parental control attempts that intrude into youths’ psychological and emotional development (Barber, 1996). Parents who express hostility and psychological control toward youth might teach adolescents that hostile, aggressive, and intrusive behaviors are an appropriate way to deal with problems in the context of relationships, a premise consistent with observational learning (Bandura, 1986). Furthermore, parental psychological control and/or hostility may negatively affect adolescents’ ability to feel connected with parents and communicate with parents about their lives. A lack of connectedness with parents may cause adolescents to feel like they do not have a secure base to rely on in order to negotiate new developmental tasks, such as friendship competence, a premise consistent with attachment-based theories (Hauser, 1991).

Research supports the proposition that parents affect the development of adolescents’ relationships with friends (Domitrovich & Bierman, 2001; Updegraff, MaddenDerdich, Estrada, Sales, & Leanord, 2002). Using cross-sectional data, higher parental hostility has been associated with lower quality friendships (Domitrovich & Bierman, 2001; Engels, Dekovic, & Meeus, 2002), and higher parental psychological control has been associated with lower quality peer relationships (Dekovic & Meeus, 1997; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Duriez, & Goossens, 2008). Using longitudinal data, Cui et al. (2002) found that parental hostility was associated with hostile behavior in adolescents’ friendships 4 years later. Their study, however, did not examine parents’ psychologically intrusive behaviors, and to our knowledge, no studies have examined this relationship prospectively. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by utilizing 5 years of longitudinal data over the course of early to middle adolescence to examine the unique effects of hostile and psychologically controlling parenting behaviors on adolescents’ friendship competence.

Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence: Potential Explanations

There are several mechanisms through which parenting behaviors may affect adolescents’ friendship competence (Parke et al., 2006). Two important mechanisms are adolescents’ behaviors and adolescents’ cognitions about relationships (Parke et al., 2006; Stocker & Youngblade, 1999). Because findings can be used to tailor interventions to youth who experience friendship difficulties, we focused on youth externalizing problems as a potentially important behavioral mechanism and emotional insecurity with parents as a potentially important cognitive mechanism.

Youths’ Externalizing Behaviors

Externalizing problems may mediate the association between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence. There are several potential reasons why externalizing behaviors might link negative parenting and youths’ friendship difficulties (e.g., genetics, selection effects; Bagwell & Coie, 2003; Pike & Eley, 2009). Capaldi and Clark (1998) have suggested that problems adolescents have in close and personal relationships result from youth developing maladaptive, patterned behaviors in response to chronic negative parenting, a premise consistent with a social learning perspective. Specifically, adolescents whose parents use harsh and intrusive means of socialization learn that hostility and psychological control are appropriate ways in which to handle conflict in interpersonal relationships. Adolescents may internalize these behaviors and develop an aggressive interaction style with others, making it difficult to develop intimacy and effectively manage conflict in friendships.

We were unable to find studies that directly tested the proposition that externalizing problems mediate the relationship between negative parenting behaviors and problems with friendship competence during adolescence. However, two areas of tangential research support the hypothesized mediating mechanism. Researchers have examined externalizing problems as a mediator of the association between negative parenting behaviors and later problems in romantic relationships (Capaldi & Clark, 1998). Capaldi and Clark found that antisocial behavior mediated the relationship between inconsistent and hostile parenting and males’ aggression toward a romantic partner during late adolescence, and concluded that adolescents’ antisocial behavior is a key factor accounting for the transmission of aggression from family-of-origin to romantic relationships. Although close friendships differ from romantic relationships (Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002), both represent important intimate relationships in which family socialization patterns may be replicated (Parke, Neville, Burks, Boyum,& Carson, 1994).

Another area of related research draws on studies that support the individual associations that comprise the mediating pathway. Parental hostility and psychological control have been associated with adolescents’ externalizing problems, both concurrently and longitudinally (Pettit, Laird, Dodge, Bates, & Criss, 2001; Williams, Conger, & Blozis, 2007). In turn, research has suggested that adolescents with externalizing problems have impaired social interactions, which make it difficult to establish intimacy and manage conflict in interpersonal relationships (Bagwell & Coie, 2003; Brendgen, Little, & Krappman, 2000). These findings suggest that youths’ externalizing problems may be one potential factor that explains why negative parenting behaviors affect adolescents’ friendship competence over time. Yet, no studies have directly tested whether maladaptive behaviors developed in the context of negative parent adolescent relationships account for the association between parenting and adolescents’ ability to be competent in their first voluntary, intimate relationships with close friends. The current study addresses this important gap.

Youths’ Emotional Insecurit

Emotional insecurity with parents may affect adolescents’ capacities to form competent relationships with friends (Bowlby, 1988; Ducharme et al., 2002). Emotional security is defined as individuals’ feelings or appraisals that they can trust in, and be supported by, an attachment figure and is thought to guide individuals’ cognitions and expectancies of self and others in interpersonal relationships (Ainsworth, 1989). Emotional security, as measured in the current study with adolescents’ perceptions of communication, alienation, and trust, has been used by others to represent attachment (El-Sheikh & Elmore-Staton, 2004; Engels et al., 2001), relational schemas (Smith, Welsh, & Fite, 2010), and parent–child relationship quality (Linder, Crick, & Collins, 2002). Theoretically, the development of emotional security with a caregiver affects relationships with peers by providing a secure base that supports exploration of the social environment and by affecting relationships with friends through individuals’ cognitions about security in relationships (Kerns, 1998). Adolescents who have strained relationships with parents may find it difficult to negotiate new developmental tasks, such as developing supportive friendships, because they do not have a secure base to rely upon when encountering new arenas (Ainsworth, 1989; Call & Mortimer, 2001). Furthermore, adolescents’ perceptions of parents as a supportive and available resource may affect the development of emotional security that governs feelings about parents, self, how they expect to be treated, and how they plan to behave in future interactions with others such as friends or romantic partners (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Weimer, Kerns, & Oldenburg, 2004).

Research supports the proposition that emotional insecurity in the parent–adolescent relationship mediates the relationship between negative parenting behaviors and problems with friendship competence (Domitrovich & Bierman, 2001; Doyle & Markiewicz, 2005). Paley, Conger, and Harold (2000) found that negative representations of parents partially mediated the positive relationship between parental hostility/ lower warmth and youths’ negative social behavior toward peers (e.g., being inconsiderate toward others). Although this study was longitudinal, and assessments occurred during adolescence, Paley and colleagues focused on social behaviors toward the larger peer group as opposed to close friendships. Friendships are conceptually distinct from peer relationships in general, and friendship quality may be characterized by different antecedents and consequences (Samter, 2003). Thus, the current study extends Paley and colleagues’ work by examining emotional insecurity with parents as a mediator of associations between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence.

Hypotheses

There is accumulating evidence that negative parenting behaviors affect youths’ friendship competence during adolescence. However, the processes by which parenting affects adolescents’ friendship competence are not understood. The findings from the current study make a significant contribution to understanding why adolescents have trouble in friendships. Accordingly, the current study tests two important hypotheses:

Parental hostility and parental psychological control during early adolescence are associated negatively with adolescents’ friendship competence during middle adolescence.

Adolescents’ externalizing problems and emotional insecurity with parents fully mediate the prospective associations between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence.

In addition to substantive contributions, this study has several methodological strengths. The research design included multiple informants, methods, and measures, as well as five waves of data across early and middle adolescence.

Methods

Sample

This study utilized data from a longitudinal project that examined the effects of family processes on the transition from childhood into adolescence. As a first step, sixth grade youth in 13 middle schools from a southeastern county during the 2001 school year were invited to participate. Youth received a letter during homeroom inviting participation, and two additional invitations were mailed directly to parents. Roughly 71 percent of the youth/parent(s) returned the consent form, and 80 percent of these youth received parental permission to complete a questionnaire on family life during school. This resulted in a sample of 2297 sixth grade students that were representative of families in the county on race, parents’ marital status, and family poverty status (contact the corresponding author for details using county census information).

As a second step, a subsample of 1131 eligible families was identified for the longitudinal study using the following criteria: parents were married, or long-term cohabitants and no stepchildren were in or out of the home. Two-parent families were chosen because the longitudinal design included a focus on parents’ marital conflict. Stepfamilies were not included for three reasons: (1) stepfamilies have complex structures that differ from ever-married families, and a careful study would need to include adequate sample sizes to conduct group comparisons; (2) data would need to be collected regarding birth parent–child relations as well as stepparent–child relations to understand the findings accurately; and (3) funds were inadequate to collect questionnaire and observational data from both stepparents and non-residential birth parents.

Primary reasons for not participating included time constraints and/or unwillingness of one or more family members to be videotaped. This resulted in a sample of 416 families who participated in the current study (37 percent response rate). This response rate was similar to that in studies that have included three or four family members and have used intensive data collection protocols (e.g., National Survey of Families and Households—34 percent). Participants were similar to eligible non-participants on all study variables reported by youth on the school-based questionnaire, suggesting minimal selection bias (contact corresponding author for statistical details).

At the onset of the study (W1), adolescents ranged in age from 11 to 14 (M = 11.90, SD = .42). Participants were primarily European-American (91 percent), and 51 percent were girls. The median level of education for parents was an associate's degree and was similar to European-American adults in the county (county mean category was some college, no degree; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000a, Table P148A of SF4). The median level of household income for participating families was slightly less than $70 000, which is higher than the median 1999 income for married European Americans in the county ($59 548, U.S. Census Bureau, 2000b, Table PCT40 of SF3; $64 689 inflation-adjusted dollars through 2001). There were 366 participating families at W2, 340 families at W3, and 330 families at W4 (79 percent retention of W1 families).

Attrition was greatest from W1 to W2, and the most common reasons given for not participating in a wave of data collection included intra-familial difficulties in coordinating a home visit and a lack of interest in completing questionnaires. Attrition analyses using multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) revealed no differences between the retained and attrited families on any of the study variables, suggesting minimal attrition bias (contact corresponding author for statistical details).

Procedures

Youth completed a questionnaire during fall of the 2001–2002 school year. During the first 4 years of data collection, questionnaires also were mailed home to youth, mothers, and fathers. Another brief questionnaire containing particularly sensitive information was completed during a home visit (e.g., adolescent antisocial behavior). The home visit also involved four videotaped family interaction tasks. Interaction tasks were based on those developed for the Iowa Youth and Family Project, and data were coded using the Iowa family interaction rating scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). For purposes of the current study, interactions from the problem-solving task were used. This task lasted 20 min and included mothers, fathers, and adolescents. The task focused on issues identified by family members on the issues checklist administered at the beginning of the home visit (Conger et al., 1992). Interactions from this task were well-suited for use in the current study, because the task was conducive to hostile parenting behavior for families so inclined (Melby, Ge, Conger, & Warner, 1995). Trained coders rated the videotaped interaction. To assess reliability of coding, 20 percent of tasks were coded by an independent rater. In-home assessments were conducted again a year later (W2), 2 years later (W3), and 3 years later (W4). Most adolescents were in seventh grade at W2 (M= 13.11, SD = .65), in eighth grade at W3 (M = 14.10, SD = .65), and in ninth grade at W4 (M = 15.10, SD = .65). Families were compensated $100 for their participation for W1, $120 for W2, $135 for W3, and $150 for W4.

During middle adolescence, youth who participated in W1 of the project were invited to participate in a telephone interview focused on adolescents’ relationships with friends. Three-hundred and eight youth participated in the W5 telephone interviews (74 percent retention rate of W1 families). These W5 telephone interviews took place about 1 year following the families’ W4 home assessment. All interviews were conducted over the telephone unless the adolescent requested that an interview protocol be mailed to his or her home (6 percent). Adolescents were asked to select a same-sex closest friend to think about when responding to statements. Most adolescents were in 10th grade at W5 (M = 16.08, SD = .64). Youth were compensated $10 for participation.

Measurement

Multiple reporters, methods, and measures were used to assess the constructs in this study. All parenting constructs and mediators consisted of data collected over a two-year period that were averaged to create latent constructs. Assessment of study variables over 2 years, rather than just 1 year, captures a more accurate array of patterned behaviors and thus increases construct validity (Cui et al., 2002). Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of parenting were considered as indicators of the same latent parenting constructs, because we were interested in assessing parenting that occurs within a given family context (Amato, 1994).

Parental Hostility

Three observational rating scales were used from the IFIRS to measure observed hostility from mother to youth and father to youth: hostility, antisocial behavior, and physical attack (Melby & Conger, 2001). Hostile behaviors included hostile, angry, contemptuous, disapproving, and critical statements toward youth. Antisocial behavior represented behavior that was insensitive, rude, egocentric, and/or unsociable. Physical attack consisted of aversive physical contact, including hitting, pinching, and/or grabbing. Coders rated parents’ behavior toward youth on a 1 (not at all characteristic) to 9 (highly characteristic) response format such that higher scores indicated greater expressed hostility. Ratings by coders on observed maternal hostility at W1 and W2 were averaged to represent one manifest indicator (r = .41), and ratings by coders on observed paternal hostility were averaged to represent observed paternal hostility as a manifest indicator (r = .39). Cronbach's alpha for observed mom hostility and observed dad hostility were both .79. Twenty percent of the interaction tasks were coded by two coders and the average level of agreement was 73 percent and 71 percent for moms’ and dads’ observed hostility, respectively. Inter-rater reliability was assessed by calculating single-item intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) based on a one-way random effect ANOVA. The ICC for the different rating scales averaged .63 for mothers and .61 for fathers, which is comparable to other studies that have used IFIRS ratings (Cui et al., 2002; Melby & Conger, 2001).

Psychological Control

The eight-item psychological control scale (PCS; Barber, 1996) and three items developed by Bogenschneider, Small, and Tsay (1997) were used to measure mothers’ and fathers’ use of psychologically intrusive behaviors toward youth at W1 and W2. Parents responded to items such as ‘I am a person who acts like I know what my child is thinking or feeling’. The response format was 1 (not like me), 2 (somewhat like me), and 3 (a lot like me) such that higher scores indicated higher levels of psychological control by parents. Cronbach's alphas ranged from .64–.77 for mothers’ and fathers’ reports at W1 and W2. Correlations between parents’ ratings at W1 and W2 were high (mother = .61, father = .55), and W1 and W2 reports were averaged for each parent yielding one manifest variable for maternal psychological control and one variable for paternal psychological control.

Externalizing Problems

Externalizing problems were measured using youths’ reports on the aggressive behavior subscale of the 118-item child behavior checklist youth self-report (Achenbach, 1991). The Achenbach measures were designed to measure adolescents’ emotional and behavioral problems. Response options were 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). The 17-item aggressive behavior subscale included items such as ‘gets in fights’. Cronbach's alpha at W3 was .89, and W4 was .90. Scores were summed, and higher scores indicated more externalizing problems.

Emotional Insecurity with Parents

A modified 12-item version of the inventory of parent and peer attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) measured youths’ perception of emotional insecurity using three subscales: the four-item alienation subscale, the four-item trust subscale, and the four-item communication subscale. The IPPA is a valid measure of adolescents’ perceptions of attachment and emotional security within the parent–adolescent relationship (Allen et al., 2003; Engels et al., 2001; Lyddon, Bradford, & Nelson, 1993). Response options on this scale ranged from 1 (almost never or never true) to 5 (almost always or always true). Youth were asked to think about their respective parent when responding to items. Higher scores on the alienation subscale and lower scores on the trust and communication subscales represented greater emotional insecurity with parents. The alienation subscale included items such as ‘I get easily upset at home’. The communication subscale included items such as ‘I tell my mother/father about my problems and troubles’. The trust subscale included items such as ‘my parents respect my feelings’. Cronbach's alphas for all three scales ranged from .77–.92 for youths’ reports regarding both mothers and fathers. Due to the high correlations (r = .59–.61) between W3 and W4 subscales and between youth reports of emotional insecurity to mothers and fathers (.35–.65), the latent construct of relational insecurity to parents was represented by three manifest variables: W3/W4 trust mother and father, W3/W4 communication mother and father, W3/W4 alienation mother and father.

Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

Youth reported on several measures that represented friendship competence. A seven-item measure of support from a same-sex close friend measured youths’ reports of support in close friendships (Berndt & Perry, 1986; Vernberg, Abwender, Ewell, & Beery, 1992). Response options ranged from 1 (never) to5 (every day). A sample item was ‘When you do a good job on something, how often does this friend praise and congratulate you’. Higher scores indicated more support in the friendship (a = .73).

The seven-item relationship assessment scale (Hendrick, 1988) assessed adolescents’ evaluation of the overall satisfaction of their same-sex closest friendship. The response scale ranged from 1 (low satisfaction) to5 (high satisfaction). A sample item was ‘How well does your friend meet your needs’. Higher scores indicated more satisfaction with the friendship (a = .73).

The conflict and antagonism subscales from the network of relationships inventory (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 1985; six items) was used to measure frequency of conflict in adolescents’ same-sex closest friendship. Youth were asked to respond on a scale from 1 (little or none) to5 (the most) to questions such as ‘How much do you and your friend disagree or quarrel’. Higher scores indicated more frequent conflicts between friends (a = .78).

Youths’ reports (W5) on seven items from the relational aggression scale (Crick, 1997) assessed behavioral responses to conflict. Adolescents responded on a scale from 1 (never true) to 5 (almost always true) to questions such as ‘When one of you or both of you is upset do you try to exclude the other from your group of friends’. Higher scores indicated more relational aggression in conflict situations with friends (a = .65).

Analytic Strategy

The AMOS 17.0 (Amos Development Corporation, Crawfordville, FL, USA) structural modeling program (SEM) was used for testing hypotheses. Model fit for all SEM analyses was examined using the chi-square goodness of fit statistic, the comparative fit indices (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A non-significant chi-square indicated a good model fit. However, because of the large sample size, a significant chi-square was expected, and additional fit indices were examined (Byrne, 2001). CFI values of .90 to .95 indicated adequate fit of the data, and values of .95 or higher indicated a good model fit. RMSEA values below .05 indicate a good model fit, and values ranging from .06 to .08 indicate an adequate model fit (Thompson, 2000). The significance threshold for all models was set at p < .05. The full information maximum likelihood estimation procedure was used to address missing values, because it produces less biased estimates than deleting cases and has been found to be comparable to other advanced techniques for handling missing data (Acock, 2005; Graham, 2009).

Structural equation models were estimated to examine the prospective associations between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence, as well as the significance of the mediators. Mediators were first tested in separate models and then tested in the same model to determine the unique effect of each mediator (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). To test whether a direct effect was fully mediated, the association between parenting and friendship competence had to reduce to nonsignificance when mediating effects were considered in the model. If the absolute size of the direct association was reduced but was still statistically significant when mediators were in the model, the mediation effect was partial (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). It was expected that externalizing problems and emotional insecurity would fully mediate the relationship between negative parenting behaviors and adolescents’ friendship competence. However, if the prospective relationship between parenting behaviors and friendship competence in the direct effects model was not statistically significant, we tested for indirect effects as opposed to mediation, and the direct effect was not retained in the mediating model (Holmbeck, 1997). Sobel's test was used to test the statistical significance of the indirect pathways.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations were calculated using SPSS (Table 1). Correlations among indicators were in the expected directions.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Inter-correlations between Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental hostility—Dad to youth | – | ||||||||||||

| 2. Parental hostility—Mom to youth | .44*** | – | |||||||||||

| 3. Psych control—MR | .03 | .11* | – | ||||||||||

| 4. Psych control—FR | .16** | .08 | .25*** | – | |||||||||

| 5. W3 Externalizing | .17** | .21*** | .26*** | .19*** | – | ||||||||

| 6. W4 Externalizing | .24*** | .28*** | .21*** | .21*** | .60*** | – | |||||||

| 7. Communication | −.10 | −.15* | −.13* | −.12* | −.33*** | −.33*** | – | ||||||

| 8. Trust | −.22*** | −.27*** | −.19*** | −.30*** | −.48*** | −.46*** | .68*** | – | |||||

| 9. Alienation | .15** | .24*** | .25** | .31*** | .44*** | .39*** | −.39*** | −.55*** | – | ||||

| 10. Friendship satisfaction | −.10* | −.11* | −.17** | −.09 | −.18** | −.23*** | .29*** | .38*** | −.35*** | – | |||

| 11. Friendship support | −.02 | −.09 | −.19*** | −.10 | −.12* | −.12* | .26*** | .23*** | −.27*** | .52*** | – | ||

| 12. Relational aggression | .02 | .06 | .17** | .10* | .07 | .07 | −.11 | −.14* | −.14* | −.35*** | −.22** | – | |

| 13. Frequency conflict | .07 | .13* | .19*** | .04 | .23*** | .19** | −.11 | −.19** | .32*** | −.44*** | −.46*** | .42*** | – |

| M | 3.14 | 3.29 | 1.29 | 1.30 | 5.02 | 4.77 | 3.47 | 4.23 | 2.31 | 4.53 | 4.12 | 1.22 | 1.47 |

| SD | 1.23 | 1.21 | .21 | .21 | 4.72 | 4.71 | .73 | .68 | .67 | .37 | .51 | .27 | .38 |

| N | 415 | 416 | 416 | 416 | 339 | 319 | 340 | 338 | 340 | 332 | 331 | 332 | 330 |

Note: MR = mother report; FR = father report; W3 = wave 3; W4 = wave 4.

p < .05

p < .01.

p < .001.

Negative Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

The first hypothesis was that parental hostility and psychological control during early adolescence is associated inversely with adolescents’ friendship competence during middle adolescence. This hypothesis was supported for psychological control. Model fit was adequate, c2 = 40.86 (17), p < .001, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .06. Parental psychological control was uniquely associated with youths’ friendship competence, b = -.36, p = .02. As such, higher parental psychological control during early adolescence was associated with problems with friendship competence in middle adolescence. Parenting predictors (W1/W2) explained 16 percent of the variance in adolescents’ friendship competence (W5). Because parental hostility was not associated significantly with friendship competence, the direct association from parental hostility to adolescents’ friendship competence was dropped from subsequent analyses and only indirect effects were estimated.

Adolescent Externalizing Problems and Emotional Insecurity with Parents

Three models were tested to examine the independent and differential effects of emotional insecurity and externalizing problems as linking mechanisms for associations between negative parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence: (1) externalizing problems as a single linking variable; (2) emotional insecurity with parents as a single linking variable, and (3) both externalizing problems and emotional insecurity as linking variables.

Youth Externalizing Problems

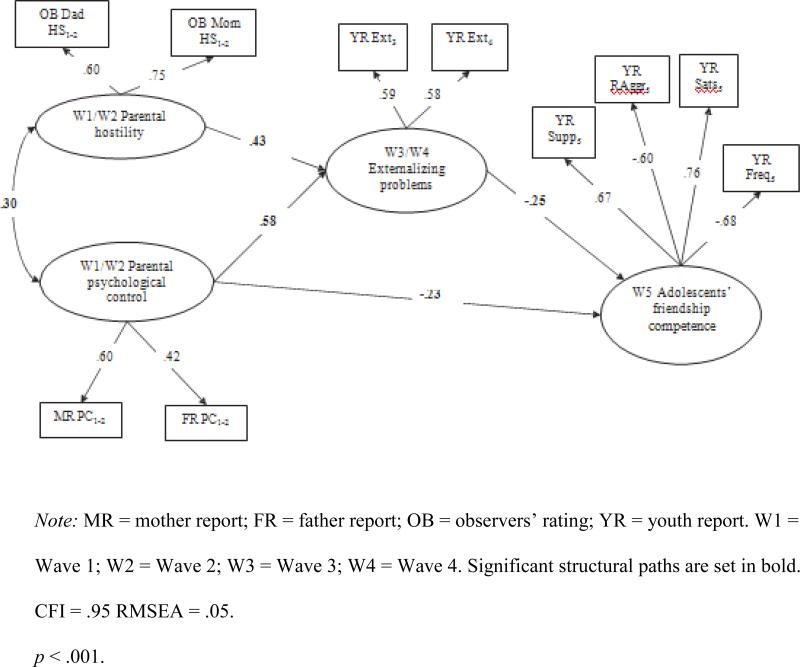

A latent construct of externalizing problems was added to the analytic model to examine the hypothesis that externalizing problems explained the association between negative parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence (Figure 1). This model fit the data well, c2 = 57.2 (29), p < .001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05. As hypothesized, parental hostility and psychological control were uniquely associated with W3–W4 externalizing problems. Externalizing problems, in turn, were significantly associated with W5 friendship competence, suggesting that adolescents who reported more externalizing problems experienced more problems in future friendships. The original significant association (b = -.36) between psychological control and friendship competence was reduced to b= -.23, p < .05 when adolescents’ externalizing problems were included in the model, suggesting partial mediation. Results from Sobel's test provided further support for partial mediation between parental psychological control and adolescents’ friendship competence through externalizing problems, z = -2.98,p = .001. The indirect pathway, parental hostility → youth externalizing problems → friendship competence, was statistically significant (z = 2.41, p < .01). Thus, results provided support for the hypothesis that negative parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence are linked over time through youths’ externalizing problems.

Figure 1.

Structural Model Examining Externalizing Problems as an Intervening Variable of the Relationship between Negative Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

Emotional Insecurity

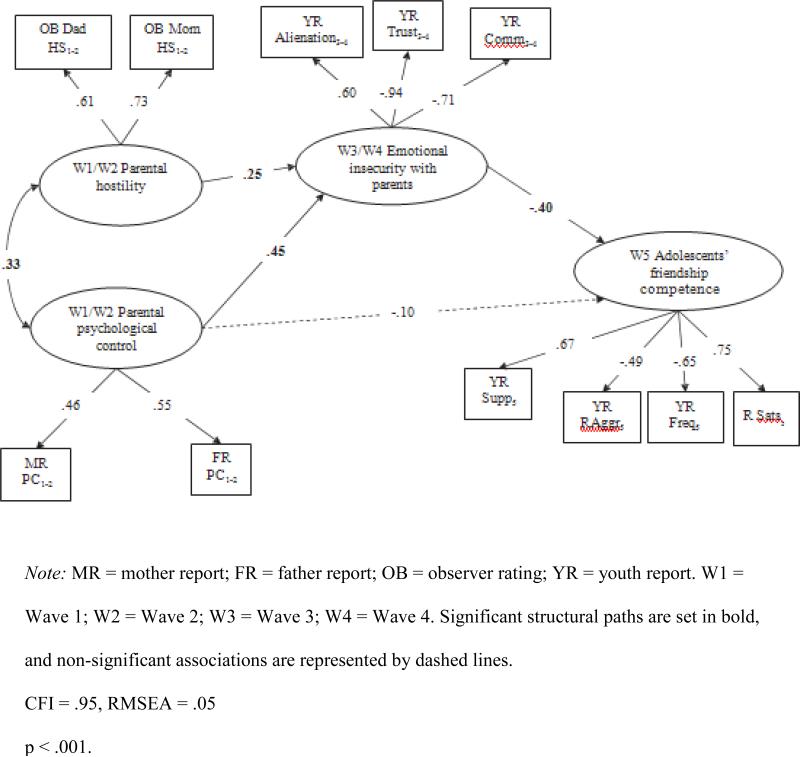

Emotional insecurity was included as a single intervening variable in a second analysis (Figure 2). Model fit was adequate, c2 = 114.3 (39), p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .06. As hypothesized, parental hostility and parental psychological control were uniquely associated with emotional insecurity with parents over time. Emotional insecurity (W3/W4) also was associated inversely with friendship competence (W5). The direct relationship between psychological control and competence became statistically non-significant when emotional insecurity was added to the model. Furthermore, Sobel's test provided support that emotional insecurity fully mediated the relationship between parental psychological control and friendship competence, z = -2.77, p < .01. The indirect pathway, parental hostility → emotional insecurity with parents → friendship competence, was statistically significant (z = -2.34, p < .01).

Figure 2.

Structural Model Examining Emotional Insecurity as an Intervening Variable of the Relationship between Negative Parenting and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

Externalizing problems and emotional insecurity in same analysis

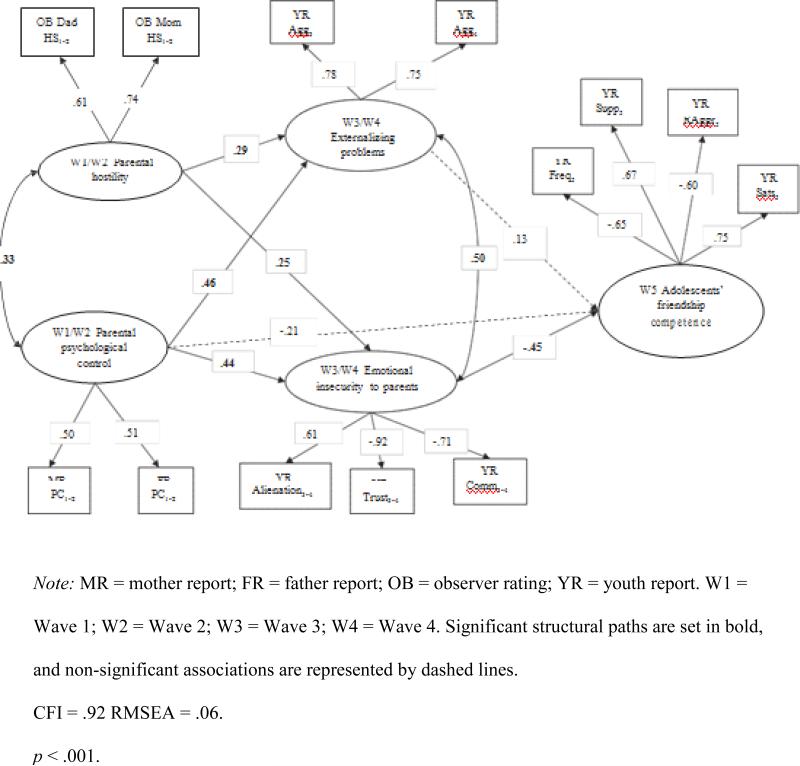

Emotional insecurity and externalizing problems were included in the same analysis to examine the relative intervening effects (Figure 3). Model fit was adequate c2 = 142.4 (55), p < .001, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .06. Parental hostility and parental psychological control were uniquely associated with both emotional insecurity and externalizing problems. Only emotional insecurity was significantly associated with adolescents’ friendship competence, b = -.45, p < .001. Externalizing problems were not associated with future friendship competence when controlling for negative parenting and youths’ emotional insecurity with parents.

Figure 3.

Final structural model examining intervening variables of the relationship between negative parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence

Emotional insecurity reduced the relationship between psychological control and friendship competence to non-significant, b = -.21, and the mediating pathway was statistically significant, z = -2.65, p < .01. When parental hostility was included in the model with parental psychological control and both intervening variables, the indirect pathway, parental hostility → emotional insecurity with parents → friendship competence, was statistically significant (z = -2.53, p < .01). Parenting explained 36 percent of the variance in future emotional insecurity, and 38 percent of the variance in future externalizing problems. Negative parenting, externalizing problems, and emotional insecurity explained 23 percent of the variance in youths’ friendship competence during middle adolescence.

Discussion

Parents help shape adolescents’ behavioral and social development (Collins & Laursen, 2004). Yet, few studies have examined the prospective relationship between parenting behaviors during early adolescence and friendship competence with agemates during middle adolescence, a developmental period within which friendships are central. Even fewer researchers have examined why these links might exist. The current study addressed these gaps and found that psychological control but not parental hostility was associated with adolescents’ friendship competence and that when both mediators were included in the model, emotional insecurity was the only intervening variable that explained the relationship between parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence. This focus on uncovering the mechanisms by which parenting affects friendship competence is important for informing theory and practice regarding interpersonal relationships during adolescence.

Negative Parenting Behaviors and Adolescents’ Friendship Competence

Results from the direct effects model provided partial support for the hypothesis that parenting behaviors during early adolescence are associated prospectively with friendship competence during middle adolescence. When parental hostility and psychological control were considered in the same analysis, only psychological control was associated with future friendship difficulties. This finding expands on previous work, by suggesting that distinct parenting behaviors may affect adolescents’ adjustment differentially (Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005). The elements of psychological control that distinguish it from hostility may explain the salience of parental psychological control. Psychological control is distinct from hostility, because it includes attempts by parents to control adolescents through intrusion into youths’ psychological and emotional development (Barber, 1996, 2002). Adolescents may be particularly susceptible to the negative effects of psychological control, because they are trying to develop autonomy while maintaining connectedness with parents, and psychological control disrupts these developmental processes. Parenting behaviors that disrupt normative developmental processes may be particularly detrimental to adolescents’ adjustment (Barber, 1996), and make it difficult for adolescents to accomplish age-related tasks, one of which is developing friendship competence. Few studies have examined psychological control as a correlate of friendship difficulties (for exceptions see Dekovic & Meeus, 1997; Soenens et al., 2008). Future research should examine psychological control as a predictor of adolescents’ friendship competence.

Externalizing Problems as an Explanatory Mechanism

Results partially supported the proposition that youths’ externalizing behaviors help explain the relationship between negative parenting and adolescents’ friendship competence. When externalizing problems were considered in a model alone, the relationship between parental psychological control and friendship competence was partially mediated by externalizing problems. These findings suggested that psychological control partly predicted friendship competence, because it contributed to adolescents’ externalizing problems, which then lead to problems with friendship competence.

One potential explanation is that adolescents who experience psychological control may have learned behavioral tendencies through interactions with parents, which might impair conflict management (i.e., use of relational aggression and frequency of conflict) and supportiveness in close friendships. Parental hostility also was indirectly associated with friendship competence, suggesting that although it was not directly associated with friendship competence during middle adolescence, it was associated with adolescents’ externalizing problems, which created difficulties with friendship competence. The finding that parental psychological control and parental hostility exert an influence on friendship competence through externalizing problems is consistent with past research suggesting that parents affect adolescents’ social development through the transmission of behavior patterns learned in the context of the family to new social environments (Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Cui et al., 2002). Our findings extend past research by highlighting the deleterious nature of intrusive control patterns within families that might then transcend familial boundaries into youths’ social relationships with friends.

Emotional Insecurity as an Explanatory Mechanism

Emotional insecurity also was an important explanatory mechanism. As expected, the relationship between psychological control and friendship competence was fully mediated by emotional insecurity. Parental hostility was indirectly associated with friendship competence through emotional insecurity. These findings contribute to the growing body of research that suggests parents indirectly affect certain aspects of adolescents’ adjustment through important transmission mechanisms, emotional insecurity, and that during adolescence one reason that parenting behaviors are important to friendship development is because they may affect youths’ cognitions about relationships that are applied to interactions with friends. Furthermore, adolescents who feel more insecurely connected to parents may feel that they cannot trust and rely on their parents for support, and thus they have more trouble developing new skills needed for friendship competence.

Evaluating the Relative Salience of Explanatory Mechanisms

One of the goals of this study was to examine whether youths’ behaviors or cognitions about relationships, or both provided the best explanation(s) for why parenting during early adolescence is associated with friendship competence during middle adolescence. When both constructs were included in the same model, emotional insecurity with parents was the only significant intervening variable. Given theory and research suggesting attachment to parents is a critical element in the development of interpersonal relationships, the finding that views regarding the parent–adolescent relationship emerged as a unique element that explains the relationship between parenting and adolescents’ first truly intimate relationship with age-mates is not surprising (Mayseless & Scharf, 2007; Rice, 1990). However, it was surprising to find that externalizing problems no longer intervened in the relationship between parenting behaviors and friendship competence. This suggests that adolescents’ cognitions about relationships may be more important than the behaviors that adolescents’ enact within relationships. These findings highlight the importance of considering and testing specialized mediating pathways between parenting behaviors and friendship competence, which is paramount in identifying the etiology of friendship problems during adolescence and developing cost-effective prevention and intervention programs (Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006). Future studies should replicate these findings, as well as examine other possible intervening variables such as rejection sensitivity and self-efficacy.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study makes an important contribution to the literature on the effects of parenting behaviors on adolescents’ friendship competence. There are, nevertheless, limitations that should be addressed in further studies.

The current study relied on prospective data but was unable to draw conclusions about causality or direction of effects. Externalizing problems, emotional insecurity, and friendship competence were not controlled for at the beginning of the study, and the research design was not experimental. Bidirectional relationships over time may exist between parenting behaviors and both externalizing problems and emotional insecurity (Burt, McGue, Krueger, & Iacono, 2005; Karavasilis, Doyle, & Markiewicz, 2003), and friendship competence could have preceded externalizing problems (Rubin, Coplan, Chen, Buskirk, & Wojslawowicz, 2005). Measures of emotional insecurity and of friendship competence were not collected at W1 of the study, and thus we were unable to control for baseline effects. However, ad hoc analyses controlling for W2 friendship satisfaction, W1 externalizing behaviors, and W1 perceived parental acceptance as a proxy for emotional security indicated that adding these controls to the model did not change substantive findings, and model fit was worse (contact corresponding author for details). This ad hoc analysis provided some support that a causal relationship might exist between parenting, mediators, and friendship competence. Furthermore, although prospective data does not provide evidence of causality, it does mark an improvement over past studies that relied on cross-sectional data and suggests a developmental perspective on how parenting behaviors affect new skills needed in friendships during a critical period of development.

In the current study, both adolescents’ reports of intervening variables and adolescents’ reports of friendship competence were used, and thus the relationship between mediators and outcomes may have been inflated due to shared method variance (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Furthermore, relying solely on adolescents’ self-report of friendship competence may not be the ideal way to assess this construct. Researchers have found that when adolescents with externalizing problems report on their own friendships, they report friendships as higher in quality than that indicated by observers’ reports (Bagwell & Coie, 2003). In addition, the current study did not assess reciprocated friendships. Past research has indicated that two friends’ perceptions of a relationship are only moderately correlated, and thus it is important to study reciprocated friendships, as well as take into account both adolescents’ and their friends’ reports of the relationship (Furman, 1998). To avoid potential method confounds, future studies should consider self-report, friend-report, and observers’ ratings of friendship competence.

A few of the measures had low reliability estimates (i.e., parental hostility, youth relational aggression). The use of structural equation modeling helped address this limitation given random error is estimated and controlled (Cole & Maxwell, 2003), but the use of these measures might have attenuated associations to some extent.

Both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors were considered as manifest indicators of parenting in analyses, which marks an improvement over past studies that only accounted for the effect of one parent's behavior on adolescents’ friendship competence. Despite the fact that the current study considered both parents’ reports, mothers’ and fathers’ parenting were not considered as unique predictors of friendship competence. Although mothers’ and fathers’ influence on development may differ (Parke et al., 2006), ad hoc analysis in the current study estimating separate models for mothers and fathers did not find any significant differences in the effects of mother's and father's negative parenting. This ad hoc analysis does not provide a stringent test of differential effects of mothers and fathers, but it does provide some evidence that in the current study mothers’ and fathers’ parenting was acting on adolescents’ development in a consistent manner. In order to take into account the shared and unique effect of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors on friendship competence, further studies should employ dominance analysis.

The generalizability of findings may be influenced by characteristics of the sample. Participants represented married families of largely European-American descent. Thus, these results may not be applicable to adolescents from different ethnic groups and family structures. To date, few studies have examined whether adolescents’ friendship processes differ based on ethnicity or family structure. Tangential research suggests that the effect of parenting behaviors on adolescents’ adjustment varies by ethnicity (Avenevoli, Sessa, & Steinberg, 1999; Collins & Laursen, 2004). Given that psychological control emerged as the primary parenting predictor of adolescents’ friendship competence, it will be especially important to examine whether this parenting behavior is as detrimental to the friendship competence of youth of other ethnicities and those having various family structures.

Conclusion

Developing friendship competence is one of the most salient developmental tasks that adolescents need to accomplish in order to transition successfully into early adulthood (Roisman et al., 2004). The current study contributes to understanding the processes that affect a critical developmental task that adolescents must accomplish. Findings from this line of research are helpful for informing intervention efforts for adolescents who have difficulty forming competent friendships.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, R01- MH59248 and the National Institutes of Health T32DA019426. We thank the staff of the Family Life Project for their unending contributions to this work and the youth, parents, teachers, and school administrators who made this research possible.

Contributor Information

Emily C. Cook, Yale University

Cheryl Buehler, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Anne C. Fletcher, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Land DJ, Kuperminc GP, Moore CW, O-Beirne-Kelly H, et al. A secure base in adolescence. Markers of attachment security in the mother-adolescent relationship. Child Development. 2003;74:293–307. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Porter MR, McFarland C. Leaders and followers in adolescent close friendships: Susceptibility to peer influence as a predictor of risk behavior, friendship instability, and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:155–172. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Father-child relations, mother-child relations, and offspring psychological well-being in early adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56:1031–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Sessa FM, Steinberg L. Family structure, parenting practices, and adolescent adjustment: An ecological examination. In: Hetherington ME, editor. Coping with divorce, single parenting, and remarriage: A risk and resiliency perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Coie JD. The best friendships of aggressive boys: Relationship quality, conflict management, and rule-breaking behavior. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2003;88:5–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. ChildDevelopment. 1996;67:296–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. How psychological control affects children and adolescents. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2005;70:1–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Perry TB. Children's perceptions of friendships as supportive relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschneider K, Small SA, Tsay JC. Child, parent, and contextual influences on perceived parenting competence among adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Little TD, Krappmann L. Rejected children and their friends: A shared evaluation of friendship quality? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Burleson BR. Personal relationships as a skilled accomplishment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- Burt AS, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. How are parent-child conflict and childhood externalizing symptoms related over time? Results from a genetically informative cross-lagged study. Developmental and Psychopathology. 2005;17:145–165. doi: 10.1017/S095457940505008X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Call KT, Mortimer JT. Arenas of comfort in adolescence: A study of adjustment in context. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AW, Laursen B. Parent-adolescent relationships and influence. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Elder GH, Bryant CM. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Engagement in gender normative versus nonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social-psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:610–617. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Conger RD, Bryant CM, Elder GH. Parental behavior and the quality of adolescent friendships: A social contextual framework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:676–689. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic M, Meeus W. Peer relations in adolescence: Effects of parenting and adolescents’ self-concept. Journal of Adolescence. 1997;20:163–176. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE. Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Bierman KL. Parenting practices and child social adjustment: Multiple pathways of influence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2001;47:235–263. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Parenting, marital conflict, and adjustment from early-to-mid-adolescence: Mediated by adolescent attachment style? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme J, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Attachment security with mother and father: Associations with adolescents’ reports of interpersonal behavior with parents and peers. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:203–231. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Elmore-Staton L. The link between marital conflict and child adjustment: Parent-child conflict and perceived attachments as mediators, potentiators, and mitigators of risk. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:631–648. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels R, Dekovic M, Meeus W. Parenting practices, social skills, and peer relationships in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality. 2002;30:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Engels R, Finkenauer C, Meeus W, Dekovic M. Parental attachment and adolescents’ emotional adjustment: The role of interpersonal tasks and social competence. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:428–439. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and Methodological Issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73:241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Almeida DM. Parents do matter: Trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Development. 2003;74:578–594. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser S. Families and their adolescents. Free Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Perceived peer context and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:391–415. [Google Scholar]

- Karavasilis L, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Associations between parenting style and attachment to mother in middle childhood and adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA. Individual differences in friendship quality: Links to child-mother attachment. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, Crick NR, Collins A. Relational aggression and victimization in young adults’ romantic relationships: Associations with perceptions of parent, peer, and romantic relationship quality. Social Development. 2002;11:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lyddon WJ, Bradford E, Nelson JP. Assessing adolescent and adult attachment: A review of current self-report measures. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1993;4:390–395. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayseless O, Scharf M. Adolescents’ attachment representations and their capacity for intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Melby J, Conger RD. The Iowa family interaction rating scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Ge X, Conger RD, Warner TD. The importance of task in evaluating positive marital interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:981–994. [Google Scholar]

- Paley B, Conger RD, Harold GT. Parents’ affect, adolescent cognitive representations, and adolescent social development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:761–776. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Morris K, Schofield T, Leidy M, Miller M, Flyr M. Parent-child relationships: Contemporary perspectives. In: Noller P, Feeney JA, editors. Close relationships: Functions, forms, and processes. Psychology Press; New York: 2006. pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Neville B, Burks VM, Boyum LA, Carson JL. Family-peer relationships: A tripartite model. In: Parke RD, Kellam SG, editors. Exploring family relationships with other social contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike A, Eley TC. Links between parenting and extra-familial relationships: Nature or nurture? Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG. Attachment in adolescence: A narrative and meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1990;19:511–538. doi: 10.1007/BF01537478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, Tellegen A. Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development. 2004;75:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Chen X, Buskirk AA, Wojslawowicz JC. Peer relationships in childhood. In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, editors. Developmental Science: An advanced textbook. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 469–512. [Google Scholar]

- Samter W. Friendship interaction skills across the life-span. In: Greene JO, Burleson BR, editors. Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NY: 2003. pp. 637–684. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin Company; Boston, MA: 2002. Chapter 2 & 3. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Welsh DP, Fite PJ. Adolescents’ relational schemas and their subjective understanding of romantic relationship interactions. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Duriez B, Goossens L. The intervening role of relational aggression between psychological control and friendship quality. Social Development. 2008;3:661–681. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Youngblade L. Marital conflict and parental hostility: Links with children's sibling and peer relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:598–609. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. Ten commandments of structural equation modeling. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 261–285. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau PCT148A. [September 29, 2004];Sex by educational attainment for the population 25 years and over (white alone) 2000a from http://factfinder.census.gov, Summary File 3.

- Census Bureau US. PCT40. Median family income in 1999 (dollars) by family type by presence of own children under 18 years. [September 3, 2005];2000b from http://factfinder.census.gov, Summary File 3.

- Updegraff KA, Madden-Derdich DA, Estrada AU, Sales LJ, Leanord SA. Young adolescents’ experiences with parents and friends: Exploring the connections. Family Relations. 2002;51:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, Abwender DA, Ewell KK, Beery SH. Social anxiety and peer relationships in early adolescence: A prospective analysis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Weimer BL, Kerns KA, Oldenburg CM. Adolescents’ interactions with a best friend: Associations with attachment style. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2004;88:102–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ST, Conger KJ, Blozis SA. The development of interpersonal aggression during adolescence: The importance of parents, siblings, and family economics. Child Development. 2007;78:1526–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]