Abstract

Background

ABO antigens are expressed on the surfaces of red blood cells and the vascular endothelium. We studied circulating endothelial microparticles (EMP) in ABO haemolytic disease of the newborn (ABO HDN) as a marker of endothelial activation to test a hypothesis of possible endothelial injury in neonates with ABO HDN, and its relation with the occurrence and severity of haemolysis.

Material and methods

Forty-five neonates with ABO HDN were compared with 20 neonates with Rhesus incompatibility (Rh HDN; haemolytic controls) and 20 healthy neonates with matched mother and infant blood groups (healthy controls). Laboratory investigations were done for markers of haemolysis and von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF Ag). EMP (CD144+) levels were measured before and after therapy (exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy).

Results

vWF Ag and pre-therapy EMP levels were higher in infants with ABO HDN or Rh HDN than in healthy controls, and were significantly higher in babies with ABO HDN than in those with Rh HDN (p<0.05). In ABO HDN, pre-therapy EMP levels were higher in patients with severe hyperbilirubinaemia than in those with mild and moderate disease or those with Rh HDN (p<0.001). Post-therapy EMP levels were lower than pre-therapy levels in both the ABO HDN and Rh HDN groups; however, the decline in EMP levels was particularly evident after exchange transfusion in ABO neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia (p<0.001). Multiple regression analysis revealed that the concentrations of haemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase and indirect bilirubin were independently correlated with pre-therapy EMP levels in ABO HDN.

Discussion

Elevated EMP levels in ABO HDN may reflect an IgG-mediated endothelial injury parallel to the IgG-mediated erythrocyte destruction and could serve as a surrogate marker of vascular dysfunction and disease severity in neonates with this condition.

Keywords: endothelial microparticles, haemolytic disease of the newborn, ABO blood group incompatibility

Introduction

Microparticles are vesicles that bud off from blood cells or vascular endothelium and vary in size from 0.2–2.0 μm. They are defined by their size and expression on their surface of antigens specific to the parental cells1,2. In the last 10 years, the identification of endothelial-derived microparticles (EMP) has raised considerable interest since these microparticles could be non-invasive biomarkers of vascular dysfunction3. EMP play a remarkable role in coagulation, inflammation, endothelial function and angiogenesis, contributing to the progression of vascular diseases4, so microparticles are not simply a consequence of disease, but may themselves contribute to pathological processes and appear to serve as both markers and mediators of pathology5. Measurement of circulating EMP (CD144+) may be of use in diagnosing vascular injury, studying its pathophysiology and progression, and in assessing the response to therapy1.

Red cell immunisation during pregnancy is a problem that continues to challenge obstetricians and blood transfusion staff6. Incompatibility of ABO blood groups between a mother and her foetus is currently the most frequent cause of haemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)7. The ABO antigens are expressed on the surfaces of red cells and many other tissues, including the vascular endothelium8,9.

The aim of this study was to determine whether circulating EMP in ABO HDN are a marker of endothelial activation in order to test the hypothesis of possible endothelial injury in neonates with ABO blood group incompatibility, and the relationship of this injury with the occurrence and severity of haemolytic disease.

Materials and methods

This study was carried on 45 neonates with ABO HDN admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Ain-Shams University Hospital in Cairo. Forty neonates were enrolled as control groups: 20 had Rh incompatibility (haemolytic controls) and 20 were healthy neonates with matched mother and infant blood groups (healthy controls). Informed consent was obtained from the parents before participation in the study. The procedures applied in this study were approved by the Ethical Committee of Human Experimentation of Ain Shams University, and are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Exclusion criteria were neonates with other causes of haemolysis (α-thalassaemia, hereditary spherocytosis, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency), neonates with congenital anomalies, clinically suspected or proven sepsis, perinatal asphyxia, large cephalo-haematoma or severe bruising, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, maternal smoking or chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune disorders.

The studied neonates were divided into three groups: group I, which had ABO HDN; group II, consisting of infants with Rh HDN, and group III, the healthy controls.

Group I (ABO HDN group) consisted of 45 neonates (16 males and 29 females, male:female ratio of 1:1.8) with blood group A or B born to mothers with blood group O without simultaneous Rh incompatibility. This group was further divided into three subgroups according to the age-specific total serum bilirubin nomogram, the severity of hyperbilirubinaemia and the management received10: group IA, 20 neonates with mild hyperbilirubinaemia that did not require phototherapy; group IB: 15 neonates with moderate hyperbilirubinaemia that required phototherapy, and group IC: 10 neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia that required exchange transfusion.

Group II (Rh HDN group) was formed of 20 neonates with Rh incompatibility (11 males and 9 females, male:female ratio of 1.2:1). Seven patients with Rh HDN received phototherapy while 9 patients had exchange transfusion.

Group III (control group) consisted of 20 age- and sex-matched healthy neonates whose blood group was compatible with that of their mothers and who had no evidence of sepsis or other medical illness. There were 11 males and 9 females in this group, with a male:female ratio of 1.2:1.

All the patients studied gave a detailed medical history and underwent a thorough clinical examination with special emphasis on ABO and Rh blood group of the mother, history of previous neonatal jaundice among siblings, gestational age, anthropometric measures, evidence of cephalo-haematoma, bruises, organomegaly, jaundice and management (exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy).

Collection of samples

Peripheral blood samples were collected into ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) (1.2 mg/mL) for haematological profiling and a direct Coombs’ test and into 0.2 mL 3.8% trisodium citrate in a ratio of 9 volumes of blood to 1 volume of citrate for flow cytometry. For the indirect antiglobulin test, chemical analysis and C-reactive protein assays (CRP), clotted samples were obtained and serum was separated by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 1,000×g.

Diagnostic testing

Laboratory investigations included ABO and Rh blood grouping performed for mothers and neonates, a complete blood count using the Sysmex XT-1800i (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan), examination of Leishman-stained peripheral blood smears for red blood cell (RBC) morphology and differential white blood cell (WBC) count, peripheral blood staining by Brilliant Cresyl blue and examination of a stained smear for reticulocyte count, antibody detection using a direct Coombs’ test (in neonates) and an indirect Coombs’ test (in the mothers), liver and kidney function tests, markers of haemolysis (lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] and indirect bilirubin) and high sensitivity CRP on a Cobas Integra 800 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Patients with clinical evidence of infection or CRP >10 mg/L were excluded. von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF Ag) was quantitatively assayed on a Sysmex CA-1500 coagulation analyser (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). Flow cytometric analysis of EMP was performed before and after therapy (exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy) using anti-CD144 (anti-human VE-Cadherin) as a specific marker11–13.

Flow cytometric analysis of endothelial microparticles

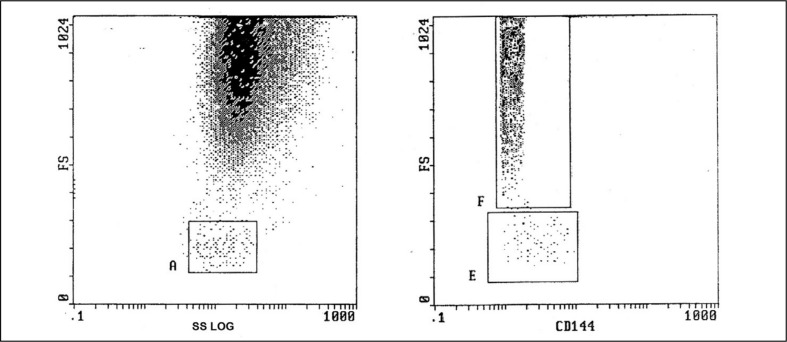

Microparticles were evaluated immediately after sampling in citrated whole blood, with this having the advantage that the microparticles were in a physiological environment, without pre-analytical steps2,14,15. Ten microliters of citrated blood were diluted with 490 μL phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA). A volume of 50 μL of the mixture was added to 5 μL of phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-CD144 (R and D systems; Minneapolis, MN, USA). Samples were protected from light and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes until data acquisition in an EPICS-XL PROFILE II Coulter flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Isotype-matched control antibodies were obtained from Beckman Coulter. EMP were identified by their characteristic forward scatter and their ability to bind the cell-specific monoclonal antibody CD144. The forward scatter cut-off was set using 1 μm standard beads (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to define the upper limit of the microparticle population16. Non-specific binding of the control mouse monoclonal antibodies set the lower fluorescence margin17. Ten thousand positive events were analysed, and EMP were reported as a percentage of total events15,18,19. The flow cytometric analysis of EMP is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of endothelial microparticles (EMPs).

The left box shows gating of platelets region by forward scatter (FS) and side scatter (SS). The right box shows identification of CD144+ EMPs by FS as a percentage of CD144+ positive events.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences, version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were described in the form of mean±standard deviation. Qualitative variables were described as number and percent. In order to compare quantitative variables between two groups, the parametric Student t-test was applied while comparisons between three groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc tests. Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square (χ2) test or Fischer’s exact test when frequencies were below five. Correlation studies were done using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Multiple regression analysis was employed to determine the relation between EMP and clinical and laboratory variables. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

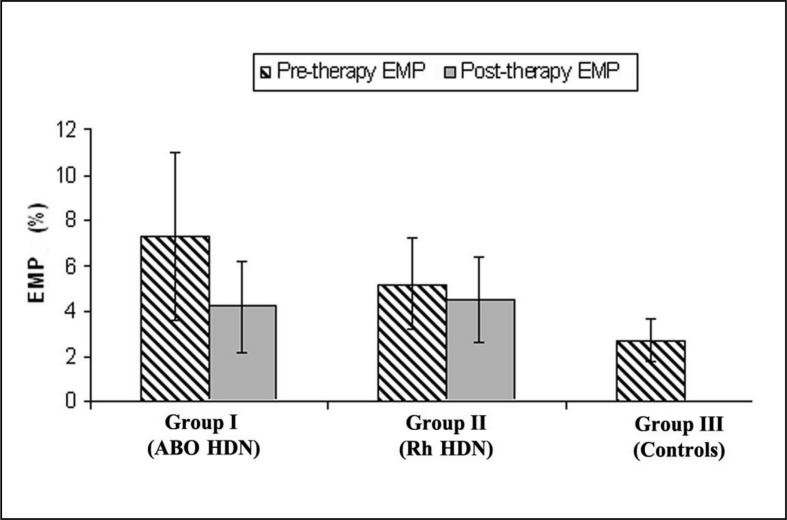

As shown in Table I, there was no significant difference between the three studied groups as regards birth weight and gestational age. Haemoglobin level and markers of haemolysis (LDH and indirect bilirubin) were statistically significantly different in both haemolytic groups compared to healthy controls (p<0.05); however, they were comparable in the ABO HDN and Rh HDN groups (p>0.05). Neonates with Rh HDN had higher reticulocytic counts than those with ABO HDN, and a 100% positive antiglobulin test compared with ABO HDN (p<0.05). vWF Ag and pre-therapy EMP levels were significantly higher in all neonates with haemolysis than in healthy controls and the highest levels were found in those with ABO HDN (group I; p<0.05). However, post-therapy EMP levels were similar in the ABO and Rh-HDN groups (p>0.05) (Figure 2).

Table I.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 3 studied groups.

| Variable | Group I (ABO HDN) n=45 |

Group II (Rh HDN) n=20 |

Group III (Healthy controls) n=20 |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Overall | I vs III | II vs III | I vs II | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 37.8±1.1 | 37.9±1.1 | 38.0±1.4 | 0.738 | 0.806 | 0.798 | 0.838 |

|

| |||||||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 16 (35.6) | 11 (55) | 11 (55) | 0.198 | - | - | - |

| Female | 29 (64.4) | 9 (45) | 9 (45) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Weight (kg) | 2.9±0.4 | 2.7±0.2 | 3.0±0.4 | 0.106 | 0.239 | 0.064 | 0.069 |

|

| |||||||

| Therapy, n (%) | |||||||

| None | 20 (44.4) | 4 (20) | 20 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.095 |

| Phototherapy | 15 (33.3) | 7 (35) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Exchange- transfusion | 10 (22.2) | 9 (45) | 0 (0) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Positive Direct Coombs’ test n (%) | 8 (17.8) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | 0.044 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Positive Indirect Coombs’ test, n (%) | 7 (15.6) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.067 |

|

| |||||||

| WBC count (×109/L) | 15.9±7.6 | 14.4±4.3 | 15.6±5.1 | 0.701 | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.4±3.9 | 15.1±2.97 | 17.9±2.8 | 0.005 | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.906 |

|

| |||||||

| Platelets (×109/L) | 261.9±69.6 | 219.1±88.4 | 275.3±86.7 | 0.058 | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 5.6±2.8 | 7.8±3.3 | 3.8±1.4 | <0.001 | 0.036 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

|

| |||||||

| LDH (IU/L) | 1,075.9±509.9 | 1,268.8±480.7 | 680±193.2 | <0.001 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.237 |

|

| |||||||

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 9.7±4.8 | 10.8±7.3 | 2.7±1.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.784 |

|

| |||||||

| vWF Ag (%) | 133±28 | 89±13 | 75±10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP pre-therapy (%) | 7.3±3.7 | 5.2±2.0 | 2.7±0.97 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.022 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP post-therapy (%) | 4.2±2.3 | 4.5±1.9 | - | 0.86 | - | - | - |

WBC: white blood cells; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; vWF Ag: von Willebrand factor antigen; EMP: endothelial microparticles; HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn. Data were expressed as mean±SD and comparisons were made using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test unless specified as n (%) where Chi-square test was used.

Figure 2.

Level of endothelial microparticles in the three groups studied.

EMP: endothelial microparticles; HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn.

When neonates with ABO HDN were divided according to the severity of hyperbilirubinaemia and management received into three subgroups, neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia (group IC) had the lowest haemoglobin level and the highest reticulocyte count, LDH, indirect bilirubin and vWF Ag levels as well as the highest incidence of positive Coombs’ test among the three subgroups (p<0.05) (Table II). As regards the level of EMP in the three subgroups of group I (Figure 3), a significant, gradual increase in pre-therapy levels was found in relation to disease severity, with the highest level occurring in neonates with severe ABO HDN (P<0.05). The levels in neonates with Rh HDN were comparable in those requiring phototherapy or exchange transfusion (4.2±1.2% vs 5.0±1.8%; p>0.05) (Figure 3). However, post-therapy levels were similar in groups 1B and 1C (p>0.05).

Table II.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics in different subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN (Group I).

| Variable | Group IA (Mild) n=20 |

Group IB (Moderate) n=15 |

Group IC (Severe) n=10 |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Overall | 1A vs 1B | 1A vs 1C | 1B vs 1C | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.2±1.3 | 37.3±0.4 | 37.67±1.03 | 0.044 | 0.036 | 0.376 | 0.665 |

|

| |||||||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 5 (25) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (40) | 0.393 | - | - | - |

| Female | 15 (75) | 8 (53.3) | 6 (60) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Weight (kg) | 3.0±0.4 | 2.9±0.4 | 2.8±0.3 | 0.408 | 0.836 | 0.375 | 0.702 |

|

| |||||||

| Direct Coombs’ test, n (%) | |||||||

| Positive | 1 (5) | 1 (6.7) | 6 (60) | 0.008 | 0.833 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Negative | 19 (95) | 14 (13.3) | 4 (40) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Indirect Coombs’ test, n (%) | |||||||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 6 (60) | <0.001 | 0.241 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Negative | 20 (100) | 14 (93.3) | 4 (40) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| WBC count (×109/L) | 16.9±5.01 | 15.1±10.3 | 14.9±7.9 | 0.746 | 0.796 | 0.805 | 0.998 |

|

| |||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.9±2.8 | 15.6±2.5 | 12.8±3.2 | 0.02 | 0.940 | 0.025 | 0.036 |

|

| |||||||

| Platelets (×109/L) | 249.9±79.7 | 271.5±49.4 | 271.9±76.8 | 0.591 | 0.643 | 0.699 | 1.0 |

|

| |||||||

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 4.3±1.5 | 4.9±1.9 | 9.7±1.7 | <0.001 | 0.288 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| LDH (IU/L) | 1,183.4±384.8 | 1,184.5±465.1 | 1,565.9±595.2 | 0.083 | 1.0 | 0.096 | 0.121 |

|

| |||||||

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.2±1.4 | 13.5±4.8 | 20.1±4.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| vWF Ag (%) | 95±9 | 107±11 | 145±15 | <0.001 | 0.689 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP pre-therapy (%) | 5.6±1.9 | 6.7±3.1 | 11.98±3.4 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP post-therapy (%) | - | 4.8±2.1 | 3.1 ±1.4 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn; WBC: white blood cells; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; vWF Ag: von Willebrand factor antigen; EMP: endothelial microparticles. Group IA (mild ABO HDN): recieved no therapy. Group IB (moderate ABO HDN): treated with phototherapy only. Group IC (severe ABO HDN): treated with exchange transfusion and phototherapy. Data were expressed as mean±SD and comparisons using ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test unless specified as n (%) where Chi-square test was used.

Figure 3.

Level of endothelial microparticles in the three subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN.

HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn.

When each of the three subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN was compared separately with healthy controls (group III), the levels of vWF Ag and pre-therapy EMP were significantly higher in all subgroups than in the healthy controls (Tables I and II; p<0.001 for all). Moreover, a comparison of the laboratory variables in the three subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN and those with Rh HDN (Table III) revealed that the neonates with ABO HDN with severe hyperbilirubinemia and those with Rh incompatibility were comparable as regards haemoglobin concentration, reticulocyte count and LDH level (p>0.05), while bilirubin levels were significantly higher in moderate and severe ABO incompatibility than in Rh incompatibility (p<0.05). ABO HDN neonates with moderate and severe hyperbilirubinaemia (group IC) had higher vWF Ag and pre-therapy EMP levels than those with Rh HDN (p<0.05). It is worth noting that pre-therapy EMP levels were significantly higher in neonates with ABO HDN with severe hyperbilirubinaemia than in those with Rh HDN with severe hyperbilirubinaemia who underwent exchange transfusion (11.98±3.4 vs 6.2±2.4; p<0.001).

Table III.

Comparison between the laboratory variables of each of the subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN (Group I) and Rh HDN (Group II).

| Variable | Group II (Rh HDN) n=20 |

Group I (ABO HDN) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Group IA (Mild) n=20 |

Group IB (Moderate) n=15 |

Group IC (Severe) n=10 |

IA vs II | IB vs II | IC vs II | ||

| Direct Coombs’ test, n (%) | |||||||

| Positive | 20 (100) | 1 (5) | 1 (6.7) | 6 (60) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 19 (95) | 14 (13.3) | 4 (40) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Indirect Coombs’ test, n (%) | |||||||

| Positive | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 6 (60) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.013 |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 14 (93.3) | 4 (40) | |||

|

| |||||||

| WBC count (×109/L) | 14.4±4.3 | 16.9±5.01 | 15.1±10.3 | 14.9±7.9 | 0.674 | 0.989 | 0.997 |

|

| |||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.4±3.9 | 15.9±2.8 | 15.6±2.5 | 12.8±3.2 | 0.973 | 0.999 | 0.155 |

|

| |||||||

| Platelets (×109/L) | 219.1±88.4 | 249.9±79.7 | 271.5±49.4 | 271.9±76.8 | 0.584 | 0.197 | 0.291 |

|

| |||||||

| MCV (fL) | 98.8±9.1 | 100.9±6.01 | 94.1±7.9 | 106.1±7.2 | 0.828 | 0.304 | 0.080 |

|

| |||||||

| MCH (pg) | 33.9±4.1 | 33.7±2.5 | 33.0±2.7 | 35.1±3.9 | 0.997 | 0.871 | 0.777 |

|

| |||||||

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 7.8±3.3 | 4.3±1.5 | 4.9±1.9 | 9.7±1.7 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.153 |

|

| |||||||

| LDH (IU/L) | 1,268.8±480.7 | 1,183.4±384.8 | 1,184.5±465.1 | 1,565.9±595.2 | 0.893 | 0.910 | 0.05 |

|

| |||||||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 11.3±7.4 | 4.6±1.4 | 14.01±4.9 | 20.7 ±4 | <0.001 | 0.034 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 10.8±7.3 | 4.2±1.4 | 13.5±4.8 | 20.1±4.07 | <0.001 | 0.038 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| vWF Ag (%) | 89±13 | 95±9 | 107±11 | 145±15 | 0.165 | 0.057 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP pre-therapy (%) | 5.2±2.0 | 5.6±1.9 | 6.7±3.1 | 11.98±3.4 | 0.948 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| EMP post-therapy (%) | 4.5±1.9 | - | 4.8±2.1 | 3.1 ±1.4 | - | 0.987 | <0.001 |

WBC: white blood cells; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; vWF Ag: von Willebrand factor antigen; EMP: endothelial microparticles; HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn. Data were expressed as mean±SD and comparisons were made using Student t-test unless specified as n (%) where Chi-square test was used.

Strikingly, post-therapy EMP levels were significantly decreased after exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy compared with pre-therapy levels (p<0.001) in both the ABO HDN and Rh HDN groups; however, the decline in EMP levels was particularly evident in ABO HDN neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia who underwent exchange transfusion when compared to both their baseline pre-exchange levels or group IB post-phototherapy levels (p<0.001) (Table IV).

Table IV.

Endothelial microparticles in relation to therapy among the studied groups.

| Variable | Endothelial microparticles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Group I (ABO HDN) n=45 | Group II (Rh HDN) n=20 | |||

|

| ||||

| mean±SD | p-value | mean±SD | p-value | |

| Pre-therapy (exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy) | 7.3±3.7 | <0.001 | 5.2±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Post-therapy (exchange transfusion and/or phototherapy) | 4.2±2.3 | 4.5±1.9 | ||

|

| ||||

| Pre-phototherapy | 6.4±3.1 | 0.003 | 4.1±1.2 | 0.002 |

| Post-phototherapy | 4.8±2.1 | 3.7±1.2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Pre-exchange transfusion | 11.98±3.4 | <0.001 | 6.2±2.4 | 0.005 |

| Post-exchange transfusion | 3.1 ±1.4 | 5.3±2.3 | ||

|

| ||||

| Post-phototherapy | 4.8±2.1 | <0.001 | 3.7±1.2 | 0.094 |

| Post-exchange transfusion | 3.1±1.4 | 5.3±2.3 | ||

HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn.

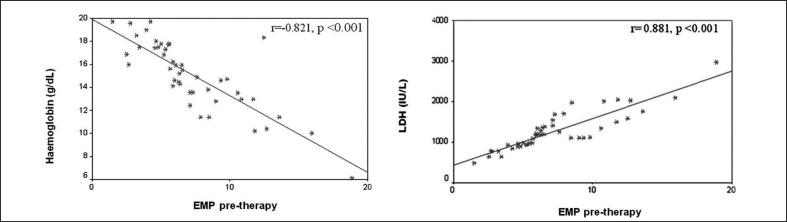

Correlation studies showed significant positive relations between pre-therapy EMP levels and those of LDH, indirect bilirubin and vWF Ag while pre-therapy EMP levels were inversely correlated with haemoglobin concentration in both the ABO HDN and Rh HDN groups (p<0.05) (Figure 4). Pre-therapy EMP levels were positively correlated with reticulocyte count only in ABO HDN neonates (p<0.05). Multiple regression analysis revealed that haemoglobin, LDH and indirect bilirubin levels were independently correlated with pre-therapy EMP levels in ABO HDN neonates (r2=0.834, p<0.001), while in the Rh HDN group, only haemoglobin and LDH concentrations were strongly correlated with pre-therapy EMP levels (r2=0.877, p<0.001) (Table V).

Figure 4.

Significant correlations between pre-therapy level of endothelial microparticles (EMP) and laboratory variables in neonates with ABO HDN (group I).

HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn.

Table V.

Multiple regression analysis of the relation between pre-therapy endothelial microparticles levels and laboratory variables in ABO and Rh HDN group.

| Group | Independent variables | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | p-value | r2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| B | Standard error | Beta | ||||

| ABO HDN | (Constant) | 9.603 | 3.589 | 0.011 | 0.834 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.825 | 0.082 | −0.669 | <0.001 | ||

| LDH (IU/L) | 0.079 | 0.029 | 0.177 | 0.009 | ||

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.202 | 0.032 | 0.404 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Rh HDN | (Constant) | 6.342 | 1.104 | <0.001 | 0.887 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.241 | 0.051 | −0.461 | <0.001 | ||

| LDH (IU/L) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.593 | <0.001 | ||

Dependent variable: pre-therapy endothelial microparticles (%). HDN: haemolytic disease of the newborn; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

A and B blood group antigens are widely distributed in human tissues and organs, which is why they are known as histo-blood group antigens20. They are expressed intensely on endothelial cells21,22. We measured EMP levels as an indicator of endothelial dysfunction to investigate whether ABO HDN has any detrimental effect on the integrity of vascular endothelium and the relation of that possible endothelial injury to the severity of the haemolytic disease.

In this study, neonates with HDN, whether caused by ABO or Rh incompatibility, showed evidence of red cell haemolysis reflected by the significant fall in haemoglobin levels compared to those in healthy controls. Neonates with Rh HDN had higher reticulocytic counts, and all of them had positive antiglobulin test while neonates with ABO HDN showed low incidences of both positive direct (17.8%) and indirect (15.6%) antiglobulin tests. These results are in line with those of previous studies23,24. Interestingly, Herschel et al.25 reported that Coombs’ tests in ABO HDN neonates are either negative or only weakly positive. This denotes that the severity of haemolysis in ABO HDN does not correlate with the positivity of the direct Coombs’ test, which is often negative due to several factors including the partial neutralisation of antibodies by A and B antigens expressed on endothelial cells and other foetal tissues reducing the chances of anti-A and anti-B binding their target antigens on the foetal red blood cells26. ABO HDN cannot, therefore, be diagnosed solely by serological tests, and severe foetal and neonatal disease can occur even in the absence of a positive direct Coombs’ test. Although LDH and indirect bilirubin levels were higher in neonates with Rh HDN than in those with ABO HDN, the difference did not reach a level of statistical significance. Weng and Chiu24 also documented that haemolysis in Rh HDN is more severe than that in ABO HDN.

Several endothelial markers have been used to detect EMP, including CD31, CD34, CD51, CD54, CD62E, CD105, CD106, CD144 and CD1462,27. However, the fact that these markers are not restricted to the endothelium should be considered28. Of this extensive list, CD144 (also known as VE-cadherin) has been proposed to be one of the most specific markers for the detection of EMP because it has not yet been found to be expressed on any other blood cell in humans4,27. Anti-CD144 has been used as a marker of endothelial injury in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease12, ischaemic stroke29 and end-stage renal disease13. vWF Ag is another marker of endothelial dysfunction30.

Notably, vWF Ag and pre-therapy EMP levels were significantly higher in all neonates with haemolysis than in controls with the highest levels being found in the group with ABO HDN. We suggest that binding of anti-A and anti-B antibodies with their corresponding antigens located over the endothelium resulted in endothelial injury reflected by increased levels of vWF Ag and EMP, suggesting endothelial dysfunction. This endothelial injury may not be clinically manifested after birth or even during childhood but it will definitely have a serious impact later on in life, as it could be the substrate for organ failure and other serious consequences.

Although prolonged, randomised clinical trials are needed to obtain unequivocal evidence, there is so much proof about endothelial dysfunction that it is reasonable to believe that it has diagnostic and prognostic value for the late outcome and could be considered an independent vascular risk factor31. Endothelial dysfunction has been previously shown to be present and contribute to progression in several disease processes, such as coronary heart disease and diabetes32,33. Alterations in endothelial function precede morphological atherosclerotic changes and can also contribute to their development with later clinical complications34. Moreover, increased microparticles and their correlation with alterations in aortic elastic properties were observed in young patients with chronic haemolytic anaemia, indicating the presence of a subclinical state of endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis before clinically evident cardiovascular abnormalities in adult life35,36. Chronic endothelial alterations are also postulated to impair multiple aspects of renal physiology and, in turn, contribute to chronic kidney disease and renal fibrosis37–39.

Our findings might actually reflect IgG-mediated endothelial damage in ABO HDN parallel to the IgG-mediated erythrocyte destruction rather than a haemolytic injury. The possibility of endothelial injury induced by haemolysis was excluded by the significantly greater increase of EMP in neonates with ABO HDN than in those with Rh HDN, although markers of haemolysis were either higher in the Rh HDN group or did not differ between the two haemolytic groups.

This hypothesis is supported by Agre and Cartron40 and Calhoun and Petz41 who documented that ABO blood group antigens are the most antigenic and immunogenic among the numerous blood group antigens. Additionally, Calhoun and Petz29 showed that Rh antigens are not expressed on vascular endothelium while ABO antigens are strongly expressed: this means that the antigen-antibody reaction in Rh HDN takes place only on the surface of red blood cells, resulting in haemolysis of these cells which may cause mild endothelial injury in an indirect way. In contrast, in ABO HDN, the antigen-antibody reaction takes place on the surface of endothelial cells as well as red blood cells, resulting in a much more severe and direct endothelial injury. ABO HDN might, therefore, have a serious impact on the endothelium, although this was not investigated in those neonates.

In this study, the overall comparison between the three subgroups of neonates with ABO HDN revealed a gradual decrease in haemoglobin levels, whereas markers of accelerated haemolysis increased progressively with increasing severity of the disease. In the ABO HDN group pre-therapy EMP levels were significantly higher in neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia than in those with moderate or mild disease, while in neonates with Rh HDN, EMP levels were not related to disease severity. These results further support the presence of endothelial injury, related to disease severity, in neonates with ABO HDN, and imply that elevated EMP levels could serve as a surrogate marker of vascular dysfunction and disease severity in such neonates.

On comparing each of the three subgroups of ABO HDN separately with the Rh HDN group, neonates with Rh HDN had lower haemoglobin levels than ABO HDN neonates with mild and moderate hyperbilirubinemia, although higher levels than in neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia. In this context, Stoll42 reported that haemoglobin levels in Rh HDN are variable and usually proportional to the severity of the disease, probably because of compensatory bone marrow and extramedullary haematopoiesis. Although ABO HDN neonates with severe hyperbilirubinaemia and those with Rh incompatibility were comparable as regards reticulocyte count and LDH level, pre-therapy EMP levels were higher in ABO HDN subgroups than in the Rh HDN group implying the possibility of endothelial injury irrespective of haemolysis.

In this analysis, pre-therapy EMP levels were positively correlated with reticulocyte count, indirect bilirubin, LDH and vWF Ag levels and inversely correlated with haemoglobin concentration in both the ABO HDN and Rh HDN groups. Ataga et al.43 and Villagra et al.44 reported that levels of EMP were positively correlated with markers of haemolysis and inversely correlated with haemoglobin level in sickle cell disease. Moreover, pre-therapy EMP, vWF Ag and D-dimer levels were significantly elevated in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and treatment with eculizumab was associated with significant decreases in these markers45.

Post-therapy EMP levels were significantly lower than pre-therapy levels in both HDN groups but the greatest decrease was found after exchange transfusion in the ABO HDN group compared with the baseline or post-phototherapy levels. We, therefore, assume that exchange transfusion had washed out the antigen-antibody reaction on endothelium and EMP, rather than actually lowering their release, whereas phototherapy just lowered bilirubin levels rather than eliminating the causative antigen-antibody reaction.

To the best of our knowledge, the occurrence of an antigen-antibody reaction at the level of the vascular endothelium resulting in endothelial injury in neonates with ABO HDN has not been explored. A similar hypothesis at the renal level has been described in the context of transplacental isoimmunisation by maternal antibodies46–48. For instance, Nauta et al.47 found that maternal serum contained IgG antibodies that reacted with tubular brush borders and glomeruli of foetal human kidneys. Debiec et al.48 also found anti-neutral endopeptidase antibodies in an infant’s serum 13 days after birth which disappeared thereafter, suggesting passive transplacental isoimmunisation. These antibodies were responsible for the infant’s membranous glomerulonephritis. The concept of endothelial dysfunction associated with ABO HDN is, therefore, plausible and should be taken into consideration when dealing with such neonates.

Furthermore, the possibility of endothelial injury in patients undergoing ABO incompatible haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) should also be considered but remains to be elucidated. While ABO antigen matching is of paramount importance for solid organ transplantation, HSCT can be performed across ABO barriers. Approximately one third of allogeneic HSCT are performed between ABO mismatched donor-recipient pairs. However, the effects of ABO incompatibility on engraftment, early and late transplant complications, relapse rate, and survival remain controversial49. Ozkurt et al.49 found that minor ABO-mismatched HSCT may have an unfavourable effect on transplant-related mortality and overall survival, while major mismatched grafts had a negative impact on survival, possibly by increasing transfusion requirements, with resulting iron overload.

Generally, endothelial dysfunction contributes to the state of vascular inflammation and promotes atherosclerosis through up-regulation of adhesion molecules, increased chemokine secretion and leucocyte adherence, increased cell permeability, enhanced low-density lipoprotein oxidation, oxidative stress, platelet activation, cytokine processing, and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration50,51. In addition, EMP can promote coagulation, inflammation, or angiogenesis. An angiogenic response may have deleterious effects with regards to the spread of cancer, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and atherosclerotic plaque destabilisation by promoting intraplaque neovascularisation4.

The present study had the limitation of not assessing other soluble endothelial cell markers such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin. Although we found increased vWF in ABO HDN and a significant correlation with EMP, further analysis of other markers would provide additional information.

In conclusion, we suggest that binding of anti-A and anti-B antibodies with their corresponding antigens located on the endothelium may result in endothelial dysfunction that could be the gateway to possible organ failure. Elevated levels of EMP in ABO HDN might reflect an IgG-mediated endothelial injury parallel to the IgG-mediated erythrocyte destruction and may be potentially useful for risk stratification and to monitor treatment response in affected neonates. Measurement of EMP in neonates with HDN might help to define patients at risk of severe vascular dysfunction. However, the proof of this concept remains to be fully elucidated and poses important challenges for risk stratification, disease progression and therapeutic response. Further prospective studies are needed to investigate long-term organ affection in ABO HDN.

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Piccin A, Murphy WG, Smith OP. Circulating microparticles: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Blood Rev. 2007;21:157–71. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnier L, Fontana P, Kwak BR, Angelillo-Scherrer A. Cell-derived microparticles in haemostasis and vascular medicine. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:439–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabatier F, Camoin-Jau L, Anfosso F, et al. Circulating endothelial cells, microparticles and progenitors: key players towards the definition of vascular competence. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:454–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dignat-George F, Boulanger CM. The many faces of endothelial microparticles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:27–33. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger D, Schock S, Thompson CS, et al. Microparticles: biomarkers and beyond. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:423–41. doi: 10.1042/CS20120309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pahuja S, Gupta SK, Pujani M, Jain M. The prevalence of irregular erythrocyte antibodies among antenatal women in Delhi. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:388–93. doi: 10.2450/2011.0050-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin S, Jerome RN, Epelbaum MI, et al. Addressing hemolysis in an infant due to mother-infant ABO blood incompatibility. J Med Libr Assoc. 2008;96:183–8. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.96.3.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravn V, Dabelsteen E. Tissue distribution of histo-blood group antigens. APMIS. 2000;108:1–28. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartron JP, Colin Y. Structural and functional diversity of blood group antigens. Transfus Clin Biol. 2001;8:163–99. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(01)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114:297–316. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amabile N, Guerin AP, Leroyer A, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3381–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koga H, Sugiyama S, Kugiyama K, et al. Elevated levels of VE-cadherin-positive endothelial microparticles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1622–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Guerin AP, et al. In vivo shear stress determines circulating levels of endothelial microparticles in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2007;49:902–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259667.22309.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattanapanyasat K, Gonwong S, Chaichompoo P, et al. Activated platelet-derived microparticles in thalassaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:462–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Davis-Gorman G, Watson RR, McDonagh PF. Platelet CD62p expression and microparticle in murine acquired immune deficiency syndrome and chronic ethanol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:25–30. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabatier F, Darmon P, Hugel B, et al. Type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients display different patterns of cellular microparticles. Diabetes. 2002;51:2840–5. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiser T, Buck F, Meyer BJ, et al. In vivo platelet activation is increased during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2002;69:229–34. doi: 10.1159/000063625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shigeta O, Kojima H, Jikuya T, et al. Aprotinin inhibits plasmin-induced platelet activation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1997;96:569–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horigome H, Hiramatsu Y, Shigeta O, et al. Overproduction of platelet microparticles in cyanotic congenital heart disease with polycythemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1072–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarafian V, Tomova E. Phylogenetic Study on the Expression of Human Histo-blood group Antigens A and B in Vertebrate Liver. Trakia J Sci. 2004;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarafian V, Dikov D, Karaivanov M, et al. Differential expression of ABH histo-blood group antigens and LAMPs in infantile hemangioma. J Mol Histol. 2005;36:455–60. doi: 10.1007/s10735-006-9017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nosaka M, Ishida Y, Tanaka A, et al. Aberrant expression of histo-blood group A type 3 antigens in vascular endothelial cells in inflammatory sites. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:223–31. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7290.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Regan F. Management of pregnancies with RhD alloimmunisation. BMJ. 2005;330:1255–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7502.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weng YH, Chiu YW. Spectrum and outcome analysis of marked neonatal hyperbilirubinemia with blood group incompatibility. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:400–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herschel M, Karrison T, Wen M, et al. Evaluation of the direct antiglobulin (Coombs’) test for identifying newborns at risk for hemolysis as determined by end-tidal carbon monoxide concentration (ETCOc); and comparison of the Coombs’ test with ETCOc for detecting significant jaundice. J Perinatol. 2002;22:341–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbaniak SJ, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and the newborn. Blood Rev. 2000;14:44–61. doi: 10.1054/blre.1999.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shet AS. Characterizing blood microparticles: technical aspects and challenges. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:769–74. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabelink TJ, de Boer HC, van Zonneveld AJ. Endothelial activation and circulating markers of endothelial activation in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:404–14. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simak J, Gelderman MP, Yu H, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles in acute ischemic stroke: a link to severity, lesion volume and outcome. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horvath B, Hegedus D, Szapary L, et al. Measurement of von Willebrand factor as the marker of endothelial dysfunction in vascular diseases. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2004;9:31–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esper RJ, Nordaby RA, Vilarino JO, et al. Endothelial dysfunction: a comprehensive appraisal. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Candido R, Zanetti M. Current perspective. Diabetic vascular disease: from endothelial dysfunction to atherosclerosis. Ital Heart J. 2005;6:703–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munzel T, Sinning C, Post F, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and prognostic implications of endothelial dysfunction. Ann Med. 2008;40:180–96. doi: 10.1080/07853890701854702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Ismail EA, et al. Circulating platelet and erythrocyte microparticles in young children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: Relation to cardiovascular complications. Platelets. 2013;24(8):605–14. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.749397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Ismail EA, Habeeb NM. Flow cytometric assessment of circulating platelet and erythrocytes microparticles in young thalassemia major patients: relation to pulmonary hypertension and aortic wall stiffness. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90:508–18. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu-Wong JR. Endothelial dysfunction and chronic kidney disease: treatment options. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;9:970–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malyszko J. Mechanism of endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1412–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guerrot D, Dussaule JC, Kavvadas P, et al. Progression of renal fibrosis: the underestimated role of endothelial alterations. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5(Suppl 1):15. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-S1-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agre P, Cartron JP. Molecular biology of the Rh antigens. Blood. 1991;78:551–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calhoun L, Petz LD. Erythrocyte antigens and antibodies. In: Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller BS, et al., editors. Williams Hematology. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill; NewYork: 2001. pp. 1843–59. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoll BJ. Blood Disorders. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Text Book of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Saunders; Philadedelphia: 2007. pp. 766–75. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ataga KI, Moore CG, Hillery CA, et al. Coagulation activation and inflammation in sickle cell disease-associated pulmonary hypertension. Haematologica. 2008;93:20–6. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villagra J, Shiva S, Hunter LA, et al. Platelet activation in patients with sickle disease, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and nitric oxide scavenging by cell-free hemoglobin. Blood. 2007;110:2166–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helley D, de Latour RP, Porcher R, et al. Evaluation of hemostasis and endothelial function in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria receiving eculizumab. Haematologica. 2010;95:574–81. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehman DH, Lee S, Wilson CB, Dixon FJ. Induction of antitubular basement membrane antibodies in rats by renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1974;17:429–31. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197404000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nauta J, de Heer E, Baldwin WM, 3rd, et al. Transplacental induction of membranous nephropathy in a neonate. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990;4:111–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00858820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Debiec H, Guigonis V, Mougenot B, et al. Antenatal membranous glomerulonephritis with vascular injury induced by anti-neutral endopeptidase antibodies: toward new concepts in the pathogenesis of glomerular diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(Suppl 1):27–32. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000067649.64849.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozkurt ZN, Yegin ZA, Yenicesu I, et al. Impact of ABO-incompatible donor on early and late outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3851–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadi HA, Carr CS, Al Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1:183–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galle J, Quaschning T, Seibold S, Wanner C. Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation: what is the link? Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;(84):S45–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s84.12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]