Abstract

Objective

To examine the impact of maternal blood glucose (BG) level and body mass index (BMI) measured at gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) screening on the risk of macrosomia.

Design

A perinatal cohort of women were followed up from receiving perinatal healthcare to giving birth.

Setting

Beichen District, Tianjin, China between June 2011 and October 2012.

Participants

1951 women aged 19–42 years with valid values of BMI and BG level at GDM screening (24–28 weeks gestation), singleton birth and birth weight (BW)>2500 g.

Main outcomes and measures

Primary outcome was macrosomia (BW>4000 g). BG level and BMI were measured at GDM screening.

Results

191 (9.7%) newborns were macrosomia. The ORs (95% CIs) of macrosomia from multiple logistic regression were 1.14 (1.10 to 1.19, p<0.0001) for BMI and 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23, p=0.03) for BG. When BMI and BG levels (continuous) were modelled simultaneously, the OR for BMI was similar, but significantly attenuated for BG. Areas of receiver operating characteristics (ROC) were 0.6530 (0.6258 to 0.6803) for BMI and 0.5548 (0.5248 to 0.5848) for BG (χ2=26.17, p<0.0001). BG (mmol/L, <6.7, 6.7–7.8 or ≥7.8) and BMI in quintiles (Q1–Q5) were evaluated with BG <6.7 and Q2 BMI as the reference group. The ORs of macrosomia were not statistically different for mothers in Q1 or Q2 of BMI regardless of the BG levels; the ORs for ≥Q3 of BMI were elevated significantly with the highest OR observed in Q5 of BMI and BG levels ≥7.8 (6.93 (2.61 to 18.43), p<0.0001).

Conclusions

High BMI measured at GDM screening was the most important determinant for risk of macrosomia. These findings suggest that GDM screening may be a critical gestational time point to initiate maternal weight control oriented intervention strategy to lower the risk.

Keywords: Epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Community-based cohort study with a high-participation rate.

The impacts of maternal glucose level and body mass measured at gestational diabetes mellitus screening have been examined simultaneously.

The results were from Chinese women only and this may affect its generalisability.

Introduction

Pedersen proposed several decades ago that maternal hyperglycaemia contributes to increased risk of macrosomia during pregnancy.1 This hypothesis becomes the foundation of prevention strategies to reduce the risk of macrosomia among women with diabetes.2 In current practice, to reduce risk, the focus for women with pre-pregnant diabetes or gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is to normalise glucose levels. The continuously increasing incidence of macrosomia during the past three decades in developed and developing countries,3 4 however, suggests that more effective strategies are needed. This is a particularly pressing need given the rising prevalence of diabetes and obesity in pregnant women.3

There is no universal standard for screening GDM. Many countries, including China, use a two-step approach. First, all pregnant women at 24–28 weeks gestation undergo a 1 h 50 g oral glucose challenge test (GCT) and, second, women with a positive GCT undergo a fasting 2 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). An abnormal glucose value from OGTT (fasting ≥5.1, 1 h ≥10.0 or 2 h ≥8.5 (mmol/L)) provokes an intervention for GDM.5 However, emerging evidence indicates that maternal glucose levels at either of GCT or OGTT is associated with the risk of macrosomia.6 7 This, coupled with evidence that actively treating pregnant women with hyperglycaemia reduces the incidence of macrosomia,8 9 suggests that a more aggressive approach may be beneficial. Maternal hyperglycaemia is also associated with maternal obesity status,10 11 and maternal obesity before pregnancy and weight gain during pregnancy are highly associated with the risk of macrosomia in women with or without GDM.7 12 13 The relative impact of obesity and hyperglycaemia on the risk for macrosomia is not understood. Some studies report a greater risk for macrosomia with maternal glucose intolerance,2 14 while others report that maternal obesity and weight gain in pregnancy have a greater influence.12 13 Ehrenberg et al12 examined the relative contribution of maternal pre-pregnant weight and diabetes status on the prevalence of larger-for-gestational-age (LGA). They found that pre-pregnant body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 was associated with a 60% increased risk for LGA and the adjusted OR for women with pregestational diabetes was 4.4 times higher in comparison to those without pregestational diabetes. They argued that since overweight and obesity are much more prevalent in pregnant women than in women with diabetes (46.7% vs 4.1%), abnormal maternal body habitus has the strongest influence on the prevalence of LGA delivery. A Canadian study by Retnakaran et al13 suggested that among women without GDM, maternal adiposity is among the strongest determinants for risk of LGA. However, none of these studies directly compared the relative effect of maternal glucose levels and BMI on the risk of having large infants.

In this study, we aimed to examine the effect of maternal glucose levels and BMI measured at GCT on the risk of macrosomia. We hypothesise that maternal blood glucose (BG) levels and BMI measured at GCT are associated with the risk of having larger infants at birth, but believe that maternal BMI may present the stronger risk.

Methods

Participants

Data were from a perinatal cohort conducted in the Beichen District Women and Children's Health Center (WCHC) of the city of Tianjin, China. The Beichen District has a population of approximately 600 000 people with about 2000 live-births annually. Prenatal care services are delivered through a three-tier perinatal care network system consisting of primary hospitals, district level WCHC (including secondary hospitals) and a city level WCHC (including tertiary hospitals). The protocol of the perinatal care network requires all pregnant women to register with a primary hospital within their district level WCHC around the 12-week gestation point in order to receive prenatal care services. After registration, each receives a unique ID card, linking them to a database in the city level WCHC, where electronical records are kept of all prenatal services. The study was conducted between June 2011 and October 2012 and details of the design and data collection are found elsewhere.15 In brief, a prospective perinatal cohort study was initiated in June 2011 to examine the impact of BG level at the GDM screening on perinatal outcome. Between June 2011 and March 2012, 2364 pregnant women from Beichen District were invited to participate in this study when coming for registration for receiving perinatal services at approximately 12 weeks of gestation and they were then followed until the time of giving birth. This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Boards from Brock University and the city of WCHC of Tianjin. All women provided their informed consent. Since GDM screening in the city of Tianjin is mandatory and a two-step approach is used for screening, each of these women underwent a 1 h 50 g GCT within 24–28 weeks of gestation. After excluding maternal age less than 19 years (n=4), multiple births (n=49), invalid GCT measures (n=41), birth weight (BW) less than 2500 g (n=44), gestation at GCT either less than 23 weeks or greater than 28.9 weeks (n=139) and/or missing measurements of weight or height at GCT (n=135), a total of 1951 women with a singleton birth remained for analysis.

Information collected at GCT

Women come to the primary hospitals for GDM screening at 24–28 weeks of gestation. Sixty minutes after ingestion of 200 mL of 25% glucose solution (taken within 5 min), the BG level was measured using a capillary glucose meter with finger blood. Women with BG levels ≥7.8 mmol/L need to be further diagnosed for GDM16; while women with BG levels <6.7 mmol/L had the lowest incidence rates for adverse perinatal outcomes.6 Therefore, we categorised participants into three groups based on their BG levels, that is, <6.7 mmol/L (n=827); 6.7–7.8 mmol/L (n=579) and ≥7.8 mmol/L (n=545). The gestational length at GCT was recorded as weeks+days, and calculated as the time from having the GCT to the date of the last menstrual period.

Participant's weight at GCT was measured to 0.1 kg with the person wearing light clothing. Height was self-reported, but if the woman was uncertain of her height, height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in squared metres. Since there are no criteria of using BMI measured at GDM screening to define overweight and/or obese among pregnant women, quintiles of BMI were then used to group participants into five categories (BMI (kg/m2), Q1 <22.6, Q2: 22.6 ∼, Q3: 24.2 ∼, Q4: 26.0 ∼, Q5: 28.4+). Blood pressure was measured using a calibrated mercury sphygmomanometer, regular cuff size (unless obese) following a 5 min seated rest period.

Obstetric outcomes

Gestational age was calculated as the weeks+days between the date of giving birth and date of the last menstrual period. BW was measured to the nearest 0.1 g using a digital scale in the delivery suite after the baby was dried but before breast feeding. Macrosomia was defined as BW larger than 4000 g. We have also defined LGA as BW larger than the 90th centile for gestational age of Chinese singletons. The cut-offs of LGA for the Chinese population, however, were much lower than those for populations from the western countries; for example, the cut-offs of LGA of singletons at 40 weeks of gestation was 3749 g for Chinese newborns,17 4034 g for Canadian females18 and 4060 for American newborns.19 Therefore, in this study, we only reported the results related to macrosomia, though there were similar results when using LGA as the outcome.

Covariates used in the analysis

A questionnaire was used to collect demographic information at about 12 weeks of gestation. This was the point when pregnant women came for registration to receive prenatal care services in primary hospitals. Maternal age was calculated according to date of birth into years, marital status (yes vs no), education (<9 years vs ≥9 years), Han-ethnicity (yes vs no) and urban residence status (yes vs no). In addition, a positive disease history (yes) was defined as having had any of the following illnesses: liver disease, kidney disease, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, tuberculosis, hyperthyroid, hypothyroid or any other diseases that may affect the mother's and the children's vital status during the pregnancy. Having maternity insurance (yes) was defined as if the woman's employer paid for her insurance or she purchased insurance for herself.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using StataSE12 with two-tail tests and with an α≦0.05 set for statistical significance. χ2 Tests were used for categorical variables and Student t test for continuous variables in the univariate analyses. Logistic regression models were used to examine the risk association of having larger infants with maternal BG and BMI measured at the GCT. Maternal glucose or BMI was first introduced into the model separately as a continuous variable, and then both were added into the model simultaneously. In addition, we did receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis to test whether the ROC curve from maternal BMI was similar to that for BG level (without covariates). Furthermore, we examined the ORs of macrosomia with maternal BMI in quintiles (Q2 of maternal BMI as the reference group), and with maternal BG levels in three categories (<6.7 mmol/L as the reference group).

To examine whether maternal BMI and BG levels jointly impact the risk of having macrosomic infants, we created 14 indicator variables to reflect the joint status of maternal BMI quintiles and BG levels measured at GDM screening with BMI in Q2 and BG level <6.7 mmol/L as the reference group. The covariate variables included in the logistic regression models were maternal age, height, education, Han-ethnicity, residence, marital status, maternity insurance, systolic blood pressure, gestational age at GCT, gestational age at birth, past disease history and infant’s sex.

Results

Overall, 9.8% newborns were considered as macrosomic. The characteristics of participants by fetus sex are shown in table 1. The maternal demographic characteristics in male infants were different from those in female infants in Han-ethnicity (90.6% vs 93.5%, p<0.05), education less than 9 years (17.1% vs 23.3%, p<0.01), with maternity insurance (55.0% vs 49.7%, p<0.05), positive disease history (4.9% vs 2.9%, p<0.05) and urban residence (75.4% vs 69.9%, p<0.01). There was no statistical difference between sexes in maternal age. The mean levels of measurements at GCT were similar between sexes except for mothers of male infants whose systolic blood pressure was higher (109.2 vs 107.9 mm Hg, p<0.01). Male infants in general had a shorter gestational age (39.4 vs 39.7 weeks, p<0.001) and larger BW (3445 vs 3375.3 g, p<0.001); however, there was no statistical difference in macrosomia between sexes (10.3% in male infants vs 9.2% in female infants, p>0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1951 singleton births by infant's gender

| Boys | Girls | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=994 | n=957 | ||

| Maternal demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years, mean (SD)) | 26.9 (3.6) | 27.1 (3.9) | NS |

| Han-nationality (% (n)) | 90.6 (901) | 93.5 (895) | <0.05 |

| Education <9 years (% (n)) | 17.1 (170) | 23.3 (223) | <0.01 |

| With maternity insurance (% (n)) | 55 (547) | 49.7 (476) | <0.05 |

| A positive disease history (% (n)) | 4.9 (49) | 2.9 (28) | <0.05 |

| Urban residence (% (n)) | 75.4 (749) | 69.9 (666) | <0.01 |

| Variables measured at GCT | |||

| Gestation at GCT (weeks, mean, (SD)) | 25.1 (1.2) | 25.1 (1.1) | NS |

| SBP (mm Hg, mean (SD)) | 109.2 (11.1) | 107.9 (10.9) | <0.01 |

| DBP (mm Hg, mean (SD)) | 70.2 (7.8) | 69.6 (7.5) | NS |

| BG at GCT (mmol/L, mean (SD)) | 7.05 (1.50) | 7.06 (1.60) | NS |

| BG categories (% (n)) | NS | ||

| <6.70 mmol/L | 41.2 (409) | 43.7(418) | |

| 6.70–7.79 mmol/L | 30.8 (306) | 28.5 (273) | |

| ≥7.80 mmol/L | 28.1 (279) | 27.8 (266) | |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean (SD)) | 25.6 (3.5) | 25.6 (3.8) | NS |

| BMI quintiles (% (n)) | NS | ||

| Q1 | 18.9 (188) | 20.2 (193) | |

| Q2 | 19.7 (196) | 20.3 (194) | |

| Q3 | 20.4 (203) | 20.1 (192) | |

| Q4 | 22.3 (222) | 17.9 (171) | |

| Q5 | 18.6 (185) | 21.6 (207) | |

| Height (cm, mean (SD)) | 162.7 (5.0) | 162.5 (4.7) | NS |

| Children's characteristics at birth | |||

| Gestation at birth (weeks, mean (SD)) | 39.4 (1.2) | 39.7 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g, mean (SD)) | 3445 (409.3) | 3375.3 (413.4) | <0.001 |

| Birth weight >4000 g (% (n)) | 10.4 (103) | 9.2 (88) | NS |

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GCT, glucose challenge test; NS, not significant; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The results of ORs of macrosomia for maternal BG levels and BMI measured at the time of GCT as continuous variables are shown in table 2. After adjustment for all covariates previously mentioned, when maternal BMI was added into the model, the ORs of macrosomia were increased by 14% for every additional unit of BMI (OR (95% CI,1.14, (1.10 to 1.19), p<0.0001). When maternal BG level was added into the model, the OR (95% CIs) of macrosomia was 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23, p=0.03). When maternal BMI and BG level were added into the model simultaneously, the ORs for maternal BMI remained at a similar level; however, the ORs for BG level were attenuated with the ORs (95% CIs) now 1.07 (0.97 to 1.18, p=0.18) for macrosomia. The results of ROC analysis showed that the under area of ROC (UAR; 95% CIs) were 0.5514 (0.5078 to 0.5950) for BG level and 0.6455 (0.6065 to 0.6845) for maternal BMI when macrosomia was the outcome. Compared with BMI measured at GDM screening, maternal BG had a lower specificity when having a similar sensitivity; for example, when sensitivity was approximately 70%, the specificity was approximately 38% for maternal BG and 52% for BMI, respectively. The difference of UAR between maternal BG and BMI level was statistically significant (χ2=10.97, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Adjusted ORs of macrosomia for BMI and BG level measured at GCT

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Models for BMI and BG separately | |||

| BMI | 1.14 | (1.10 to 1.19) | <0.0001 |

| BG | 1.11 | (1.01 to 1.23) | 0.03 |

| Models for BMI+BG simultaneously | |||

| BMI | 1.14 | (1.09 to 1.19) | <0.0001 |

| BG | 1.07 | (0.97 to 1.18) | 0.18 |

Adjustment for maternal age, height, education, nationality and residence, infant's gender, gestational age at GCT, systolic blood pressure, maternity insurance, disease history and gestational age at birth.

BG, blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; GCT, glucose challenge test.

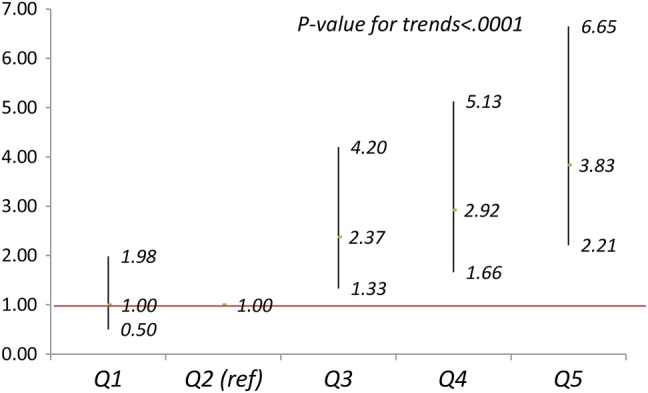

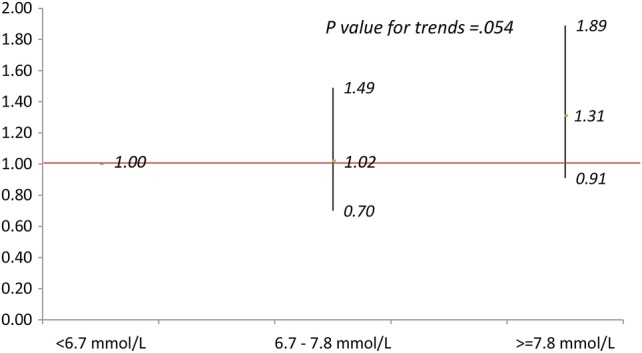

The ORs (95% CIs) of having macrosomic infants are shown in figure 1 for maternal BMI and figure 2 for BG level as categorical variables. After adjustment for covariates, compared with mothers in the Q2 of BMI (figure 1), the ORs (95% CIs) of macrosomia for mothers in Q1, Q3–Q5 were 1.00 (0.50 to 1.98, p=0.99), 2.37 (1.33 to 4.20, p<0.005), 2.92 (1.66 to 5.13, p<0.0001) and 3.83 (2.21 to 6.65, p<0.0001), respectively, and the p value for trends was less than 0.0001. Compared with mothers with BG<6.7 mmol/L, the ORs (95% CIs) of macrosomia were 1.02 (0.70 to 1.49, p=0.98) for mothers with BG 6.7–7.8 mmol/L, and 1.31 (0.90 to 1.89, p=0.15) for mothers with BG ≥7.8 mmol/L, (p value for trends= 0.054) (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Adjusted ORs (95% CI) of macrosomia for body mass index (BMI) at glucose challenge test (GCT) in quintiles. Adjusting for maternal age, height, education, Han-ethnicity, residence, maternity insurance, systolic blood pressure, disease history, gestation weeks at GCT, infant's sex and gestation weeks at birth.

Figure 2.

Adjusted ORs (95% CI) of macrosomia for blood glucose (BG) at glucose challenge test (GCT) in three groups. Adjusting for maternal age, height, education, Han-ethnicity, residence, maternity insurance, systolic blood pressure, disease history, gestation weeks at GCT, infant's sex and gestation weeks at birth.

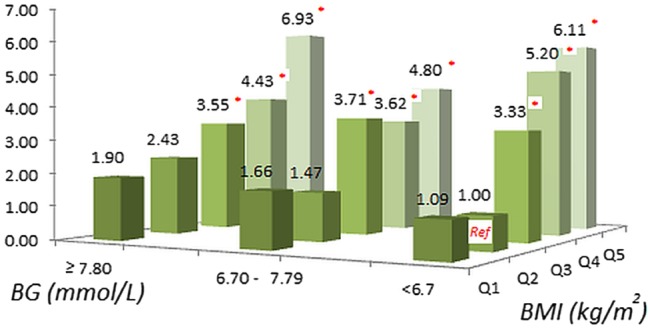

Although obese women are at risk for GDM, the levels of maternal BG were weakly associated with BMI measured at GDM screening (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.18, p<0.001). Thus, we examined the joint impact of these two variables on the risk of macrosomia (figure 3). Compared with mothers in the Q2 of BMI and with BG<6.7 mmol/L, the ORs of having macrosomic infants were not statistically different for mothers in the Q1 or Q2 of BMI regardless of their BG levels; while the ORs of macrosomia for those in the third or higher quintiles of BMI were, in general, elevated significantly with the highest odds observed in mothers within the Q5 of BMI and BG≥7.8 mmol/L (6.93 (2.61 to 18.43), p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Adjusted ORs of macrosomia for blood glucose (BG) at glucose challenge test (GCT) in three groups and body mass index (BMI) at GCT in quintiles. Adjusting for maternal age, height, education, Han-ethnicity, residence, maternity insurance, systolic blood pressure, disease history, gestation weeks at GCT, infant's sex and gestation weeks at birth.

Discussion

Using the data collected in this perinatal cohort, we examined the effect of maternal BG level and BMI measured at the time of the GDM screening test (24–28 weeks gestation) on the risk of macrosomia. We found that the elevated levels of BG and BMI measured at GCT were independently associated with an increased risk for macrosomia. This held true after adjustment for a number of other known risk factors. These findings are consistent with observations from previous studies.13 20 21 Yet emerging evidence suggests that maternal pre-pregnancy obesity is also an important determinant of macrosomia.12 13 22 23 When maternal glucose levels and BMI were simultaneously added into the model as continuous variables, the risk association with BMI did not change, but the risk association with maternal BG levels was significantly attenuated. This provides evidence that maternal obesity status might play a more important role than BG levels on the risk for larger infants at birth. ROC analyses results also indicated that maternal BMI was a much stronger risk predictor of having larger infants in comparison to maternal BG levels. Results from the models with jointly categorised maternal BG levels and BMI further demonstrated that maternal BMI may be a major contributor to increase risk for macrosomic infants at birth.

As discussed previously, a number of studies have examined the impact of maternal weight status on the risk of macrosomia; their foci on maternal weight status are pre-pregnancy BMI12 13 and/or weight gain during the pregnancy.7 13 Our study is the first to examine the risk association of macrosomia with maternal BMI measured at GDM screening (24–28 weeks gestation). BMI measured at 24–28 weeks gestation varied among women with different gestational length, which may introduce bias. However, we argue that restricting participants within 23–28.9 weeks of gestation and adjusting for gestational age at GCT will limit the impact of the bias. Women who are overweight/obese before pregnancy should be encouraged to pay much more attention to their weight gain during pregnancy in order to reduce the ORs of macrosomia. Women with normal weight before pregnancy, however, may not be aware that too much weight gain during pregnancy may increase the risk for a larger infant at birth. Therefore, BMI measured at GDM screening (24–28 weeks gestation) may be critical. Since many countries have implemented a mandatory, universal GDM screening programme, this would provide a great opportunity to address concerns with maternal BMI during pregnancy. The results from this study suggest that a maternal BMI-orientated intervention may be an effective strategy for lowering the risk of larger infants at birth. This would be applicable to women with either hyperglycaemia, high BMI or both at GDM screening.

Compared with other studies, several features may make this study unique. First, we excluded those participants whose infants’ BW was less than 2500 g. Since low BW infants were more likely to be born to mothers with low pre-pregnancy BMI,24 including them may have introduced a potential bias on the observed risk association of macrosomia with maternal BMI. Second, the majority of the participants in this study were relatively young (the mean age was 27 years with 94% less than 35 years of age) with a very low prevalence of pregestational diabetes (one woman had type 1 diabetes before pregnancy), though approximately 8.5% of them were diagnosed as GDM during the pregnancy. Older mothers or mothers with pregestational diabetes are more likely to have larger sized infants.25 26 Therefore, the observed relationship between maternal BG level, BMI and larger infants at birth were not biased by these factors and the actual population risk may be underplayed. Third, in the multiple logistic regression analyses, we adjusted for maternal height, which has been ignored in most other studies.12 13 25 The rationale for adjustment for maternal height is that neonatal phenotype is highly associated with maternal size and body composition,27 which is a proxy indicator of maternal genetic make-up and nutritional needs.28 It has been previously argued that maternal height should be taken into account when studying macrosomia-related issues.29 30 Fourth, we adjusted for gestational age at birth. Women with longer gestational length were more likely to have heavier babies at birth; therefore, adjusting for it would avoid the potential biases introduced in BW as the outcome.

Several limitations of the study need to be kept in mind when trying to apply its results. First, the calculation of gestational age was based on the date of self-reported last menstrual period, and no data were available for the measurements of crown-rump length in the first trimester to verify its accuracy. However, we expected that the potential inaccuracy of gestational age due to menstrual irregularities would not be different in each exposure group, and therefore its impact on the observed risk association should be limited. Second, the information of pre-pregnancy weight was not available in this study, so we could not examine the affect of maternal weight during the early stage of pregnancy on the risk of having macrosomic infants. Third, the mother's height used for calculation of BMI at GCT was self-reported in most women. Self-reported height may contain recall bias, but it is considered to be reliable particularly among young female adults.31 Fourth, we had only one time point of maternal BG level measurement, which may not represent the true level of maternal BG. The major strength of this study is that the participants were from a perinatal cohort, which represented well the study population in the city of Tianjin. However, one needs to be cautious when applying the results of this study to other ethnicity groups, since all women from this study are Chinese.

In conclusion, among women, of whom the majority were free of diabetes, a high level of maternal BMI measured at GCT was the most important determinant for the risk of having macrosomic infants. More research is needed to confirm whether using GDM screening as a critical gestational time point to address the impact of maternal BMI on the risk of macrosomia will provide an opening to lower the risk for having larger infants at birth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all women and their children who participated in this study and medical staffs in Beichen District who helped in collection of the related information.

Footnotes

Contributors: GL, JuL and JL conceived and designed the study. JW, ZL and YS were involved in the data collection and laboratory processing. CT was involved in data management and data preparation. JH, SW, JuL and JL framed the research theme, analysed and interpreted the data for this article. JL initiated statistical analysis and drafted the paper. JH critically revised the manuscript and all authors reviewed the important intellectual content. GL, JuL and JL are the guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by the Brock University Advancement Funds.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Research Ethics Boards of Brock University and the city WCHC of Tianjin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Pedersen J. The pregnant diabetic and her newborn: problems and management. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz R. Hyperinsulinemia and macrosomia. N Engl J Med 1990;323:340–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henriksen T. The macrosomic fetus: a challenge in current obstetrics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:134–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koyanagi A, Zhang J, Dagvadorj A, et al. Macrosomia in 23 developing countries: an analysis of a multicountry, facility-based, cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2013;381:476–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang HX, Sun WJ, Cu XM, et al. Diagnosis criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus. Beijing: Ministry of Public Health, China, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yee LM, Cheng YW, Liddell J, et al. 50-Gram glucose challenge test: is it indicative of outcomes in women without gestational diabetes mellitus? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:1102–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Vesco KK, et al. Excess gestational weight gain: modifying fetal macrosomia risk associated with maternal glucose. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1007–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1339–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonomo M, Corica D, Mion E, et al. Evaluating the therapeutic approach in pregnancies complicated by borderline glucose intolerance: a randomized clinical trial. Diabet Med 2005;22:1536–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2070–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloomgarden ZT. Gestational diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e60–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM, Catalano PM. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:964–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retnakaran R, Ye C, Hanley AJ, et al. Effect of maternal weight, adipokines, glucose intolerance and lipids on infant birth weight among women without gestational diabetes mellitus. CMAJ 2012;184:1353–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jovanovic-Peterson L, Peterson CM, Reed GF, et al. Maternal postprandial glucose levels and infant birth weight: the Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development—Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164(1 Pt 1):103–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leng J, Liu G, Wang Jet al. The association between glucose challenge test level and foetal nutritional status. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27:479–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30(Suppl 2):S251–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang B, Qin Z, Jin H, et al. The variation of body composition measurements by gestational age: 15 cities newborns’ development survey of China. J Clin Paediatr (Chinese) 1991;9:6 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:E35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, et al. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:163–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons D. Relationship between maternal glycaemia and birth weight in glucose-tolerant women from different ethnic groups in New Zealand. Diabet Med 2007;24:240–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacks DA, Liu AI, Wolde-Tsadik G, et al. What proportion of birth weight is attributable to maternal glucose among infants of diabetic women? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:501–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouzounian JG, Hernandez GD, Korst LM, et al. Pre-pregnancy weight and excess weight gain are risk factors for macrosomia in women with gestational diabetes. J Perinatol 2011;31:717–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao C, Zhou Y, Jiang LS, et al. Reasons for the increasing incidence of macrosomia in Harbin, China. BJOG 2011;118:93–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadav H, Lee N. Maternal factors in predicting low birth weight babies. Med J Malaysia 2013;68:44–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolly MC, Sebire NJ, Harris JP, et al. Risk factors for macrosomia and its clinical consequences: a study of 350,311 pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003;111:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shand AW, Bell JC, McElduff A, et al. Outcomes of pregnancies in women with pre-gestational diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes mellitus; a population-based study in New South Wales, Australia, 1998–2002. Diabet Med 2008;25:708–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.[No authors listed] Maternal anthropometry and pregnancy outcomes. A WHO Collaborative Study. Bull World Health Organ 1995;73(Suppl):1–98 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Sempos C. Foetal nutritional status and cardiovascular risk profile among children. Public Health Nutr 2007;10:1067–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazouni C, Porcu G, Cohen-Solal E, et al. Maternal and anthropomorphic risk factors for shoulder dystocia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006;85:567–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monasta L. Maternal height should be considered in the evaluation of macrosomia related risk of infant injuries at birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:198; author reply 198–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ezzati M, Martin H, Skjold S, et al. Trends in national and state-level obesity in the USA after correction for self-report bias: analysis of health surveys. J R Soc Med 2006;99:250–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.